Peacemaker

tear your world apart once the magic starts

The 1840s were not shaping up to be John Tyler’s decade.

They’d started off strong. In 1840 Tippecanoe and Tyler Too handily beat Little Van in that year’s presidential election. Then in 1841 Tippecanoe kicked the bucket, making Tyler Too the first vice president to take over after his predecessor’s death. In 1842, his beloved wife Letitia passed away. Somewhere along the way he’d managed to get expelled from the Whig Party after pissing off every one of its most influential members.

President Tyler’s cardinal sin was vetoing legislation written by Whig Party leader Henry Clay. After one veto too many, Clay organized the mass resignation of the entire cabinet, with only Secretary of State Daniel Webster choosing to stay on. He hoped the stunt would either frighten the president into compliance or shame him into resigning. It backfired spectacularly, instead giving Tyler the chance to rebuild the cabinet of party loyalists he’d inherited from William Henry Harrison with ambitious and far-sighted men who put country above party.

One of these new men was Secretary of the Navy Abel P. Upshur. Within weeks of his appointment Upshur began pushing for reforms that would drag the Navy kicking and screaming into the 19th Century. There was one problem with his plan: Congress would never pass it, because it was too expensive. In the end, the legislature only gave Upshur a few crumbs, mostly the funds to build a few experimental steam-powered vessels.

Enter Captain Robert Field Stockton. Stockton came from a rich and distinguished New Jersey family known for their patriotism. He had dropped out of Princeton to join the Navy during the War of 1812, and had served with distinction in the intervening years. He was charming, noble, intelligent, and resourceful. He was also vainglorious and stubborn. A subordinate once called him a “spoiled child of fortune, with just enough brains to keep it together and not enough to know that in public matters, money does not screen the pulpit.” Which is to say, he was a rich kid used to buying his way out of problems.

On a diplomatic trip to England in 1837, Stockton was introduced to inventor John Ericsson. Ericsson was a Swedish mechanical engineer whose twin passions were steam power and ship design. His engines burned hotter and generated more power than everyone else’s, and he used them to drive the first reliable system of screw propulsion. A prototype tug designed by Ericsson once towed a 140-ton schooner against the tide at 6 knots.

Ericsson was frustrated; in spite of his success in the commercial sphere, he could not get the British Admiralty to take his proposals seriously. Stockton offered him a deal: come back with me and design ships for Uncle Sam. Just one problem: the meager funds the Navy had set aside for experimental ships had been given to Matthew Perry, who was building the side-paddle steamships that would eventually take him to Japan.

When Tyler’s cabinet resigned en masse in 1841, Stockton was the first person he offered the Secretary of the Navy job to. Stockton declined, because he didn’t want to be a paper-pusher, but did use his newfound influence to browbeat Secretary Upshur into green-lighting his pet project.

The USS Princeton

It took two years and $210,000 — much of it out of Stockton’s own pocket — but eventually his baby, the USS Princeton, was complete.

From the outside, the Princeton wasn’t very imposing. It was only 164′ long with a 30′ beam and a 17′ draft, displacing about 900 tons. Inside, though, the ship was powered by two seawater-cooled Ericsson Vibrating Link Engines that drove a six-bladed bronze propeller screw. The engines were powered by three tubular iron boilers, which burned smokeless anthracite coal (reducing the ship’s visibility when the ship was under steam) and vented through a telescoping smokestack (which could be lowered to reduce wind resistance when the ship was under sail). The entire system only weighed 85 tons and fit neatly into 1,700 cubic feet. That allowed it to sit below the the water line, making it relatively impervious to enemy fire. It also freed up space on deck, and that space was used to mount as many guns as humanly possible. That included twelve 42 lb. carronades, which were standard equipment, but the long guns were something else.

Ericsson had designed the first one, a massive 12″ cannon. It was a revolutionary design, made of wrought iron at the Mersey Ironworks in Liverpool. The increased strength of wrought iron allowed the gun to be longer and take more powder. Ericsson named it “The Orator,” because when it spoke, people listened. Stockton renamed it the “Oregon,” which is a much lamer name. The Oregon could hurl a 200 lb. shot over five miles and through 6′ of solid oak. It was also equipped with range finders and elevation gauges calibrated to the yaw of the ship, a compressor brake system to minimize recoil, and a pivot mount allowing it to be aimed more freely. During the ship’s construction the Oregon was extensively test fired, and developed small tension cracks from the barrel to the trunnions. To arrest the development of these cracks, Ericsson had reinforcing bands shrunk down onto the breech. After that, the gun was perfect.

As work on the Princeton continued Stockton began to think the ship should have an American-made gun on board as a point of national pride. He went to the firm of Hogg & DeLamater in New York and asked them to make a copy of the the Oregon, only bigger. The result was not only the largest naval cannon ever made, it was the largest mass of wrought iron ever forged. Ericsson did not think it was particularly well made. Stockton didn’t care. He named the gun “The Peacemaker” and had it immediately. There was no need for testing, since it was identical to the Oregon, after all.

On September 5, 1843 the USS Princeton was christened at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. A large crowd turned out to see the spectacle in spite of the heavy rain. At 1:15 PM a bottle of good old American whiskey was smashed across the prow and the Princeton slid out of dry dock into the Delaware. The cheering crowd accidentally knocked a young girl into the river, but she was quickly fished out. That afternoon Stockton threw a lavish party for 200 high society guests on board the ship. That evening he threw an equally lavish afterparty for the 300 workers who built it.

For the next several months, the Princeton split its time between New York and Philadelphia. It could do this because it was incredibly fast — it took a while to break through the ice on the Delaware and reach open water, but it could reach Manhattan from New Castle in two and a half hours. (You can’t even do that on I-95 today.)

One reason for the split schedule was that the Princeton was still being outfitted with armaments and other equipment. The other reason was that Stockton was wooing the press in the nation’s two largest media markets. He led tours of the ships for thousands of curious tourists, gave speeches to any civic group that would have him, and wrote letters to the press full of outlandish claims. Everything he did spread the glory of the USS Princeton… glory that reflected back on her captain.

Not her designer, though. Stockton had initially given all due credit to Ericsson, but as the months wore on the Swedish inventor was increasingly left out of the story. And why not? Ericsson may have done the work, but it was Stockton who had paid him to do it. (Except he hadn’t. Yes, Ericsson had received $1,500 — but Stockton still owed him $15,000 and was in no rush to pay.)

In a famous publicity stunt, the Princeton raced a side-paddle steamer on October 19th. The Great Western was the self-proclaimed “Queen of the Sea” and one of the fastest ships afloat, and the Princeton not only defeated her, but embarrassed her by circling her twice in the process. At least, that’s how Stockton framed the story. But it wasn’t really a race: Stockton saw the Great Western coming in to port and went out to lap her as a way of showing off. The Great Western was not a willing or active participant, making this less of a race, and more like an obnoxious teenager revving his engine and trying to drag anyone who pulls up beside him at a red light.

It wasn’t all good press. The Princeton’s sailors got into fights everywhere she went. She had an easily avoidable collision with a schooner that caused superficial damage. They tested her guns too close to the city, shattering windows up and down the waterfront. When the Princeton left Philadelphia for Washington, DC on February 9th it was supposed to tow the brig Caraccas out of port, but the hawser connecting the two vessels got tangled in the Princeton‘s propellor and snapped. Rather than turn around Stockton steamed on, leaving the Caraccas and its indignant captain behind.

The Caraccas wasn’t the only thing that the Princeton left behind. When she left New York at the end of January, John Ericsson was supposed to be on board, but the Swedish inventor was shocked to see Princeton steam past him and his luggage without stopping. He was angry for a minute, but let it pass. It would have been nice to go to DC, but he had plenty of work ahead of him in New York. There were more than three dozen commercial ships waiting to be outfitted with his revolutionary designs.

First in War, First in Peace

On Monday, February 13th, 1844 the Princeton made its way from Philadelphia to Washington, DC. It navigated Chesapeake Bay and worked its way up the Potomac through 40 miles of 10″ thick ice. As she passed Mount Vernon, Stockton fired a welcoming blast from the Peacemaker that could be heard miles away in the city proper. At 6:00 PM Stockton prominently anchored the Princeton in the middle of the river. This was a power play — if he’d docked at a naval base, technically the ship would be under the control of the base commander, and Stockton wasn’t going to share his glory with anyone.

Stockton was in town to testify before Congress about technological advances in ship design, the advantages of steam power, and how awesome and handsome he was. He laid it on with a trowel. Here’s some sample testimony:

It is confidently believed that this small ship will be able to battle with any vessel, however large, if she is not invincible against any foe. The improvements in the art of war, adopted on board the Princeton, may be productive of more important results than anything that has occurred since the invention of gun powder. The numerical force of other navies, so long boasted, may be set at naught. The ocean may again become neutral ground, and the right of the smallest, as well as the greatest nation may once more be respected.

Everyone was quite impressed — well, almost everyone. Curmudgeonly John Quincy Adams thought the ship was just the latest attempt by Tyler and other Southern Whigs to provoke a war between the United States and Mexico. Also unimpressed: William Montgomery Crane, Chief of the Naval Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography, who was still upset that the Princeton had been designed, procured and tested outside of the typical chain of command. He thought it was a disaster waiting to happen.

Stockton tried to sway the holdouts by conducting a series of pleasure cruises up and down the Potomac. The first cruise took place on February 16th, and guests included President Tyler, various military bigwigs, and the Congressional Committees that oversaw the Navy. As the ship sailed down and back, the band played patriotic tunes while Stockton plied the visiting dignitaries with alcohol and droned on about the ship’s inner workings. Every now and then they would fire off a shot from the Peacemaker. For the grand finale, when the Princeton reached Mount Vernon the band struck up “Hail to the Chief” and the Peacemaker would be fired one final time. It was an enormous success.

Another cruise took place on February 20th, but this time the guests were one hundred Congressmen. From all reports, the trip was identical to the first. The band played the same songs, Stockton gave the same lecture, they even fired the Peacemaker off in the same places. Stockton wasn’t varying the choreography at all. No matter; everyone was still very impressed, even John Quincy Adams.

A final cruise took place on February 28th, and this time the guests were all members of high society. It was the hottest ticket in town, with socialites scrambling to get an invitation. The guest list included:

- President John Tyler, his son John Jr. and his son-in-law William Waller.

- Almost the entire cabinet, including Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur, Secretary of War William Wilkins, Secretary of the Navy Thomas Walker Gilmer, Attorney General John Nelson, and Postmaster General Charles A. Wyckliffe.

- A who’s who of current and former Congressmen, including Thomas Hart Benton, Levi Woodbury, and George Sykes.

- Captain Beverly Kennon, chief of the Navy Bureau of Construction and Equipment.

- The reigning queen of Washington society, 75-year-old Dolley Madison, proving like Dollys throughout history that you can be fabulous at any age.

- And a few important state politicians like Virgil Maxcy of Maryland and David Gardiner of New York.

Let me correct that. It would be wrong to say that David Gardiner was important. Sure he came from a well-connected Knickerbocker family and served in the state legislature, but a politically he was a nobody. But he did have something people wanted: two smoking hot daughters.

There’s no other way to put it: Julia and Margaret Gardiner were top-of-the-line dimes. The only reason they weren’t married already was because of the scandal: a few years previously Julia had (gasp) posed for an advertisement, which was all it took to get her deemed unmarriageable by ultra-conservative New York society. In 1843 David Gardiner took his daughters down to the capital, hoping to leave the scandal behind. It worked. Julia turned the head of every bachelor in town (and a few of the married mens’ heads too).

One of her many admirers was John Tyler. Tyler had been in a deep funk after his wife Letitia’s death in September 1842. He became so despondent even the Whigs stopped attacking him — it just felt like kicking a sad puppy. When Julia Gardner showed up, he fell in love all over again. He wrote her love letters and poetry like a giddy schoolboy, and had her over to the White House so frequently people started to talk. After a year of flirting, Tyler could contain his passions no longer and had proposed to Julia. Neither Julia or her father was keen on the idea of her marrying a man thirty years her senior, but at least David Gardiner was tactful about it. Julia literally laughed in his face.

The heartbroken president did not forcefully press his suit, but he did snag a few tickets for the Princeton gala for the Gardiners. If nothing else, it would give him a few more minutes with the apple of his eye.

On February 28th, 1844 the guests boarded a ferry in Washington which took them out to the USS Princeton. Stockton waited atop the gangplank and greeted every guest personally. When Tyler came on board, the band played “Hail to the Chief” and the carronades fired off a 21-gun salute.

At 1:00 PM the ship weighed anchor and began cruising down the Potomac. Stockton assembled everyone by the big guns and gave a few safety instructions — everyone should hold on to their hats and open their mouths to dissipate the force from the blast. Then he fired the Peacemaker. The men cheered heartily, the ladies squealed in delight, and then everyone went below decks for a late lunch.

This time Stockton had gone all out, with a lavish spread of meats, fruits and cheeses all ready to be washed down by several cases of champagne. He’d even had the inner partitions of the ship removed to open up the space. There still wasn’t enough room for four hundred people to eat simultaneously, though, so the gentlemen let the ladies eat first, while they drank. Then it was back above decks to watch the Peacemaker get fired for a second time. The enormous cannonball bounced seven times off the thick ice and went four miles down the river. There were more huzzahs, and then everyone went back below so the men to eat.

Everyone was buzzed now, and things started to get rowdy. There was a series of increasingly weird toasts. President Tyler started off with a good one to “The three big guns — the Peacemaker, the Oregon, and Captain Stockton!” Secretary of the Navy Thomas Walker Gilmer responded with a bizarrely weak toast to “fair trade and sailor’s rights.”

At some point during the revels, Gilmer asked Stockton to fire off a salute to George Washington when the ship reached Mount Vernon. Stockton later claimed that he only agreed because Gilmer had given him a direct order, but this seems unlikely. So far he’d stuck to the script on every trip, and the Mount Vernon salute was the grand finale. The Peacemaker was primed for one last shot and everyone went topside to watch.

Almost everyone. Some of the guests were still eating, some were socializing, some were just drunk, and and some just didn’t want to go back out into the freezing cold.

One of the holdouts was President Tyler. He had already seen this show and didn’t need to see it again. He may have also been distracted — Secretary Wilkins had been bugging him for a word in private, and the band had just struck up his favorite songs. Or he may have stayed behind to make goo-goo eyes at Julia Gardiner, who was driving him mad as she flirted with Captain Stockton’s son.

The crowd clustered around the Peacemaker. Gilmer and Uphsur, the current and former Secretaries of the Navy, took up a position to port, about eight feet away. They were joined by Captain Kennon. Virgil Maxcy and David Gardiner, who had been conversing, were not too far away. Behind them, the president’s slave and valet, Armistead, took in the spectacle from a respectful distance.

When everyone had taken their places, Stockton strode up to the Peacemaker, struck a jaunty pose by putting his leg up on the carriage, pointed at Mt. Vernon, and smiled. Then the gunner, Lieutenant King, pulled the firing cord.

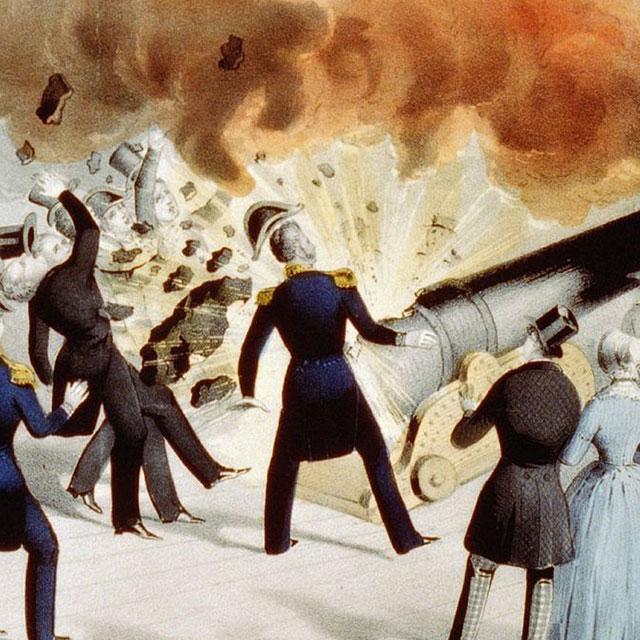

And the Peacemaker exploded.

Tiny cracks had been developing on the Peacemaker for weeks now, cracks that could have been detected and arrested if only the cannon had been tested. Now, with the Peacemaker overprimed to make the shot look more impressive, these cracks gave way. Chunks of wrought iron blew off the port side of the cannon, spraying shrapnel everywhere and smashing bulwarks for twenty feet on either side of the breach.

Everyone within thirty feet of the cannon was buffeted by the shockwave and knocked off their feet. Men’s hats were blown off of their heads and ladies’ bonnets were torn free of their chin straps. Many spectators were knocked around so fiercely they suffered concussions, bruises and broken bones. Others were sliced up by shrapnel. Almost everyone was bleeding from nose and ears.

The thick cloud of powder smoke dissipated, revealing Captain Stockton, somehow standing upright and staring blankly at the shattered gun. Flames from the blast had burned off his eyebrows and most of his sideburns, and shrapnel had pierced his leg. It could have been worse. A fragment of the gun weighing a hundred pounds had whizzed between Captain Stockton and Lieutenant King, splintering a solid oak gun carriage behind them into a thousand pieces and bending a solid iron bar like it was nothing. All things considered, Stockton was lucky. Upshur, Gilmer, Kennon, Maxcy, Gardiner, and Armistead had been standing to the port of the gun and had taken the brunt of the blast.

Secretary Gilmer was lying on his back, mouth open. He had been struck in the forehead by a fragment of the Peacemaker, and a two-ton chunk of the cannon was pinning his legs to the deck. Would-be rescuers wrestled him into a seated position, but he coughed once and died. He was bleeding so profusely that his would-be rescuers’ coats were soaked through after only a few seconds of contact.

Secretary Upshur was lying across Gilmer’s left arm, with his right hand on Gardner’s chest. Shrapnel had torn his stomach open, and his bowels had leaked out onto the deck. He had died instantly.

Gardiner had taken less of the blast than Gilmer and Upshur, but it didn’t matter. He writhed in excruciating pain for half an hour before bleeding to death. His pocket watch had stopped at the exact moment of the fatal blast — 4:06 PM.

Captain Kennon lay nearby, mangled “in the most dreadful manner.” His chest had been completely smashed in, his limbs were broken in multiple places, and one of his feet had been severed. He gave a long, long death rattle before dying.

Poor Virgil Maxcy fared worse. One of his arms had been blown off, and he literally fell to pieces when the crew tried to move his body.

Armistead had no visible injuries but had been knocked over and never got back up. For about an hour he gasped and stared blankly before dying. Two of the ship’s gunners were also killed. Nine officers and a dozen civilians were seriously injured.

Imagine the scale of this tragedy: a third of the cabinet was killed, along with a high ranking naval officer and two influential politicians. Had the explosion been bigger, had half of the cabinet not remained below decks, the entire executive branch of the United States might have been wiped out with the sole exception of Secretary of the Treasury John Canfield Spencer, who hadn’t been there.

The partiers below were completely oblivious, until they heard the screaming. They rushed topside and were greeted by the hideous carnage just described. Ladies fainted, men vomited. Upon seeing her fathers’ corpse, Julia Gardiner swooned right into the arms of President Tyler.

With Captain Stockton in a state of shock, his second, Lieutenant Johnson, took command of the situation. Some of the sailors moved the bodies to the side, covering them with an American flag, while others tended to the less seriously injured.

At 4:30 PM a steamer pulled alongside the Princeton to ferry the survivors to shore. President Tyler personally carried the unconscious Julia down the gangplank, but along the way she awoke with a start and started thrashing about violently. Her spasms almost knocked them both into the freezing Potomac, but the president was able to get her safely aboard the ferry. Then he returned to the Princeton and stood vigil over the dead men with Captain Stockton and Secretary Wilkins.

The dead men were laid in state in the White House’s East Room and were given a full state funeral three days later.

In the aftermath of the accident Congress quickly halted all funding for steam-powered propeller-driven ships — even though the steam had nothing to do with the accident.

Tyler and Stockton insisted that the explosion was a one-in-a-million accident, caused by bad luck and nothing else. To clear their names they convened an official naval court of inquiry, though Tyler telegraphed the conclusion he wanted the court to reach when he stated he had “the most perfect confidence that no censure can, with any show of justice, be imputed to either of the parties.” For a week the court interviewed survivors of the accident and every witness it could subpoena. Notably, John Ericsson did not testify — in fact, he sent word that his testimony would have been useless, since he hadn’t been present. A furious Stockton saw this as attempted character assassination and canceled the $15,000 payment that was coming Ericsson’s way. On March 11th, the court issued its pre-ordained findings. It was all just a stroke of bad luck. No one individual bore responsibility for the explosion of the Peackemaker.

A report from the House Committee of Naval Affairs begged to differ. They blamed the accident on the unorthodox process of designing the Peacemaker, which had been removed from the Navy’s oversight and testing processes. Stockton, who had been claiming sole responsibility for the design, therefore deserved all of the blame.

Seeking to clear his name, Stockton commissioned his own report from the smartest men in the country — the brainiacs at Philadelphia’s Franklin Institute. He probably shouldn’t have. The Institute released its report on August 23rd and it was damning. They announced that the Peacemaker was fundamentally flawed and it should have never been put into service. Hogg & DeLamater clearly did not have the technical expertise to work with wrought iron at this scale. If you looked carefully, you could still see the original of the iron ingots, a sign that they had not been correctly worked. They had also worked the iron in two layers to build up the thickness of the breech, but to work with iron that thick the gun had to be kept at welding temperatures for a whole day. That tends to concentrate impurities and air pockets in the iron, which can be hammered to spread them about evenly, but the foundry didn’t have any hammers heavy enough to do that. Finally, when they had added reinforcing bands to the breech in imitation of those on the Oregon, they had welded them on instead of shrinking them on. That meant they would do nothing to arrest the spread of cracks, making them purely decorative.

The Institute’s final conclusion: “In the present state of the arts, the use of wrought-iron guns of large caliber, made upon the same plan as the gun now under examination, ought to be abandoned.”

The report was careful to keep its findings limited to the realm of metallurgy, but the conclusion was inescapable. If the Oregon was fine, and the Peacemaker was a copy of the Oregon, then the fatal flaws were attributable to the small differences between the two. Changes made at the whim of one man: Captain Robert F. Stockton.

Ericsson, whose relationship with Stockton was now beyond repair, agreed, throwing more fuel on the fire when he claimed that Stockton “lack[ed] sufficient knowledge for the construction of a common wheelbarrow.”

Aftermath

The USS Princeton was rushed back into service, but only lasted another six years before being scuttled.

Tyler ordered a replica of the Peacemaker to replace the shattered original, but the Navy refused to mount it. Even though there was nothing wrong with it, the Oregon was also removed from service and put on display at the Naval Academy in Annapolis.

On April 1st the Senate confirmed Upshur’s replacement as Secretary of State, slavery apologist John C. Calhoun. Eager to tip the balance of power in Washington by admitting another slave state, Calhoun vigorously pursued Upshur’s last big project: absorbing the Republic of Texas into the Union. True to form, he pursued this goal without anything resembling tact or diplomacy, needlessly provoking Mexico and planting the seeds that would blossom into the Mexican-American War.

Captain Stockton served with distinction in that war, and afterwards served as the military governor of California. In honor of his service, the city of Stockton was named after him. In the 1850s he was politically active as a member of the American Party, or “Know-Nothings,” and served as the United States Senator from New Jersey. His culpability in the Peacemaker explosion continued to eat at him, because he never stopped commissioning studies that absolved him from blame.

John Ericsson never did get the $15,000 that Stockton owed him. He continued to apply his mechanical genius to the design of steam engines and ships. You may have heard one of his creations — the USS Monitor. He doesn’t have any cities in California named after him, but he does have his own memorial on the National Mall, just south of the Lincoln Memorial.

Survivors of the Peacemaker explosion all coped with their psychological scars in different ways. Dolley Madison, usually the chattiest of Cathys, would not speak about the events of that day no matter how hard you asked. And people asked her about it a lot.

William Montgomery Crane, the Chief of the Naval Bureau of Ordnance and Hydrography, had nothing to do with the design and testing of the Peacemaker, but couldn’t shake the feeling he might have prevented the accident with more rigorous oversight. The guilt eventually got to him and on March 18, 1846 Crane locked himself in his office and slit his throat ear to ear with a straight razor. He was survived by his brother, Ichabod Crane. (Yes, that’s where Washington Irving to the name.)

John Tyler did not get re-elected to a second term, but let’s be honest: that was never going to happen. He was so unpopular that the Whigs didn’t even renominate him. But he did find love. In the days and weeks after the explosion, Julia Gardiner found her opinion of the president had shifted. Maybe she was swayed by the way he had gallantly put her safety before his own. Maybe she just transferred her daddy issues to the next available father figure. Who knows. In April she accepted Tyler’s standing proposal of marriage, and they were wed in June. Neither of their families were happy about it, but he’s the President of the United States, what are you gonna do? John proved to be as devoted to Julia as he had been to Letitia. They had seven children and were happily married until his death seventeen years later. So at least someone in this tragedy got a happy ending.

As long as you can set aside that Tyler was a white supremacist slaveowner and Julia was New York’s most notorious Copperhead.

America!

We can’t have nice things can we?

Connections

Daniel Webster is barely in this story — but he is in this story! In his day he was the most famous of American orators and statesman, but today we know him from mostly his starring role in Steven Vincent Benet’s “The Devil and Daniel Webster.” We’ve done a few episodes about the villains from that story’s “jury of the damned” — Simon Girty (“He Whooped to See Them Burn”) and Walter Butler (“The War Between the States”).

Abel P. Upshur’s niece, Mary Jane Stith Upshur, was the ghostwriter of Josephine Bunkley’s The Escaped Nun (“Nuns on the Run”).

Sources

- Crapol, Edward P. John Tyler: The Accidental President. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

- May, Gary. John Tyler. New York: Times Books, 2008.

- O’Connell, J. Harlin. “The USS Princeton.” Princeton University Library Chronicle, Volume 1, Number 4 (June 1940).

- Pearson, Lee M. “The Princeton and the Peacemaker; A Study in Nineteenth-Century Naval Research and Development Procedures.” Technology and Culture, Volume 7, Number 2 (Spring 1966).

- Schedel, Charles W. “Ask Infoser.” Warship International, Volume 27, Number 3 (1990).

- Schedel, Charles W. “Ask Infoser.” Warship International, Volume 51, Number 3 (September 2014).

- Seager, Robert II. And Tyler Too: A Biography of John and Julia Gardiner Tyler. New York: McGraw Hill, 1963.

- Shultz, William. “Fouled Anchors and Mamelukes.” Military Images, Volume 38, Number 1 (Winter 2020).

- Sioussat, George L. “The Accident on Board the USS Princeton, February 28, 1844: A Contemporary News-Letter.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies. Volume 4, Number 3 (July 1937).

- Stockton, Robert F. “On Some of the Results of a Series of Experiments Relative to Different Parts of Gunnery.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, Volume 10 (1853).

- Walters, Kerry. Explosion on the Potomac: The 1844 Calamity Aboard the USS Princeton. Charleston, SC: THe History Press, 2013.

- “Report on the explosion of the gun on board the steam frigate ‘Princeton.'” Journal of the Franklin Institute,/cite>, Volume 38, Issue 3 (September 1844).

- “John Tyler.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Tyler Accessed 1/31/2022.

- “USS Princeton (1843).” Wikpedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Princeton_(1843) Accessed 1/26/2022.

- “Launch of the U.S. Ship Princeton.” Philadelphia Public Ledger, 5 Sep 1843.

- “The Stockton festival.” Baltimore Sun, 7 Sep 1843.

- “The launch to-day.” Philadelphia Public Ledger, 7 Sep 1843.

- “The launch.” Philadelphia Public Ledger, 8 Sep 1843.

- “A great gun.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 4 Oct 1843.

- “Progress of steam navigation — trial of speed.” New York Daily Herald, 19 Oct 1843.

- “The Great Aquatic Race.” New York Daily Herald, 20 Oct 1843.

- “The United States Steamer Princeton.” Baltimore Sun, 23 Oct 1843.

- “Gleanings.” Brooklyn Evening Star, 23 Oct 1843.

- “By the Southern Mail.” New York Daily Herald, 11 Dec 1843.

- “Accident of the Princeton.” New York Daily Herald, 24 Dec 1843.

- “By The Southern Mail.” New York Daily Herald, 30 Jan 1844.

- “Cost of the Princeton.” Buffalo Daily Gazette, 30 Jan 1844.

- “Items of news.” New York Daily Herald, 3 Feb 1844.

- “The Princeton and the Brig Caraccas.” Philadelphia Public Ledger, 10 Feb 1844.

- “The Princeton.” Baltimore Sun, 14 feb 1844.

- “By the Southern Mail.” New York Daily Herald, 16 Feb 1844.

- “By the Southern Mail.” New York Daily Herald, 19 Feb 1844.

- “Engines of destruction.” Lancaster Examiner, 28 Feb 1844.

- “Horrible accident on board the Princeton steamer!” New York Daily Herald, 1 Mar 1844.

- “Further particulars of the accident on board of the Princeton — arrangements for the funeral, &c.” The Baltimore Sun, 2 Mar 1844.

- “Washington.” New York Daily Herald, 8 Mar 1844.

- “New York Legislature.” New York Tribune, 8 Mar 1844.

- Collier, James H. “The Princeton.” New York Tribune, 3 Apr 1844.

- “U.S. Steamer ‘Princeton.'” Buffalo Daily Gazette, 27 Sep 1844.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: