Wild Frantics

the Sanctified Band of Chincoteague Island

Chincoteague Island is on the east coast of the Delmarva Peninsula, in the Tidewater region of Virginia. The name may be familiar to you if you’ve ever spent time with a horse girl who wouldn’t shut up about the feral ponies that run free on Chincoteague and neighboring Assateague Island.

These days Chincoteague is a resort town connected to the mainland by a series of bridges, but back in the Nineteenth Century it was a quiet seaside community only reachable by boat. It had an almost entirely seafood-based economy, and most of the “Chunkers” of Chincoteague worked as fishermen, oystermen, clammers, or eelers. It wasn’t until late in the century that the community began getting modern amenities like a mill, a baker, and a barbershop. Because this is America, a community that did not yet have amenities like “fresh bread” for most of the century was still somehow able to support two active churches — a Baptist Church and a Methodist Protestant Church.

Two big things changed for Chincoteague Island in 1869.

First, the Reverend J.M. McCarter and J.L. Kenney realized that the island’s population had grown large enough to support a third church, and established their own Methodist Episcopal Church.

Second, a large group of migrants from Sussex County, Delaware settled on the northern tip of the island and established a community which was variously referred to as “Delaware City”, “North Main Street”, or just plain “Up the Island.” One of the families involved in that migration was the Lynch family: Joseph Barnard Lynch, his wife Charlotte Collins Lynch, their four sons and three daughters.

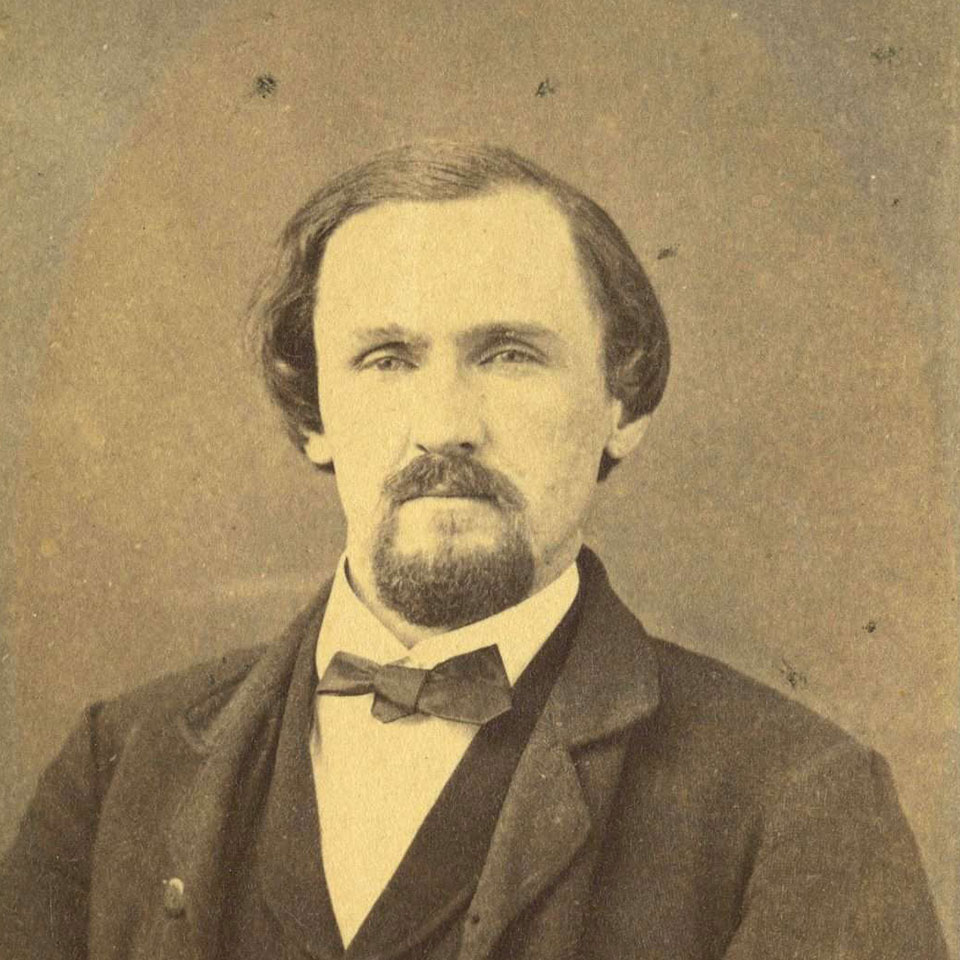

Joseph Barnard Lynch was born in 1840 in Williamsville, Delaware. He was a humble and pious man, mostly an oysterman, though he did once work as a lighthouse keeper on Assateague. He soon became one of the most respected members of the Delaware City community. In addition to his oyster beds he also ran a large farm and a general store, and at one point he was the richest man on the island.

In 1885 the Methodist Episcopal Church decided it was time to relocate to a new building, one closer to the more densely populated southern end of the island. That would effectively leave residents up the island without a church. To prevent that from happening, the Methodists sold the old building to a group of trustees that included Joseph Lynch, William Chandler, Thomas Bowden Jr., and more. The trustees agreed to maintain the building as a house of worship, and it was quickly re-opened as the non-denominational “Goodwill Independent Church.”

In 1887, Lynch began to suffer from arthritis. That was hardly surprising; he had been doing hard labor in wet conditions for most of his life. He took a trip to Philadelphia to consult a doctor to see what could be done about it.

During the trip he seems to have been exposed to the Holiness movement.

The Holiness Movement

Now, I’m going to be honest. In theory I am a lapsed Catholic, and in practice I am an agnostic secular humanist. Before researching this episode I had no idea what the Holiness Movement was, and I’m betting most of you don’t know what it is either. Understanding the movement is crucial to understanding this story, though, so here’s a brief overview.

(If you’re already hip to Holiness, feel free to skip ahead about five minutes to the next chapter. Or maybe keep listening and then roast me in the comments about everything I got wrong.)

Holiness arises out of Methodism, so let’s start there.

The first thing you need to understand is that Methodists are not Calvinists. Calvinists believe that only a small group, “the elect,” will be saved and that group has already been picked. Methodists believe that anyone can be saved.

The next thing you need to know is that Methodists believe that salvation is accomplished by two separate works of grace.

- The first work of grace, Justification, is when a believer acknowledges their sins and asks God for forgiveness. Their sins are washed away but a “residue of sin” remains behind on their soul.

- The second work of grace, Sanctification, comes when the Holy Spirit descends on the believer. The residue of sin is burned away and the believer becomes one with the Holy Will of God. While Justification is easy, Sanctification is a long and difficult process which starts from the moment of Justification, involves a lot of self-reflection and self-denial, and is generally only complete at the moment of death.

Now, let’s get into Sanctification.

At the beginning of the Nineteenth Century Methodism was a weird little movement inside the Anglican Church, and at the end of the Nineteenth Century it was its own mainstream religion. In the process it became a little less fiery, a little more staid, and a lot more socially acceptable.

One of the ways that it changed was that Justification was emphasized over Sanctification; in other words, the important part was asking God for forgiveness and you didn’t have to worry so much about the being a better person part because it would just kind of happen. Another way it changed was that the church began focusing on social justice issues.

Some Methodists were uncomfortable with this shift. They felt that the church was placing too much effort on improving the material world and not on preparing the soul for the world to come. They began several counter-movements re-emphasizing personal piety. These movements are lumped together under the umbrella of “Sanctification” and include Pentecostalism, Apostolicism, and Holiness.

Holiness emphasizes the Sanctification of the individual above all. It holds believers to a high standard of personal piety, which is usually outlined in strict codes of conduct that cover everything from how to dress to how to talk to ladies to how to do business. Some sects keep kosher, others avoid the consumption of alcohol and coffee. Those who cannot or will not obey the codes are subjected to severe punishments and ultimately excommunication.

At the same time, Holiness stresses that Sanctification is not a long and difficult process achieved through hard work. Instead, it is a gift without preconditions bestowed upon the recipient by God. While the behavioral codes can help the Justified grease the wheels, so to speak, the Holy Spirit could still descend upon them at any time. (To be fair, John Wesley had written that this sort of “instantaneous Sanctification” was possible but thought it was very very very rare.)

The strict moral code might make you think that Holiness sects are a dull and joyless lot, but most of them engage in a joyful and lively form of worship. Services often feature singing and dancing and clapping and chanting and just about everything short of speaking in tongues (and sometimes that too).

The Holiness movement began early in the century, but only kicked into high gear after the Civil War when the first “Holiness camp meeting” was held in Vineland, New Jersey in July 1867. While it failed to catch on in the Northeast and Midwest, it became wildly popular in the South.

At first Methodists welcomed the movement as a shot in the arm that was reinvigorating their faith. Soon they began to worry about some of the more unusual doctrines being promoted by Holiness preachers.

The idea of “instantaneous Sanctification” was already mildly heretical, so what was one to make of “entire Sanctification” or “sinless perfection,” the idea that the Sanctified were literally incapable of committing sin? Or “marital purity,” the idea that the only valid marriages were marriages of the spirit between the Sanctified? That doesn’t even get into the extremely obvious heresies, like the idea that the Sanctified would be free of disease or death. And I don’t even know where to start with the sects in Texas that believed in “The Fire,” a series of additional works of grace which followed Sanctification and made one progressively more holy, like a Scientologist ascending through Operating Thetan levels.

By the 1890s Methodists were actively trying to suppress Holiness theology. Ministers were rigidly locked down to specific areas in an attempt to reduce the influence of itinerant Holiness preachers. Any minister who was caught sneaking Holiness into their sermons would be banished to a remote rural area and their former congregation would be turned over someone more willing to toe the line.

Holiness responded by splitting from Methodism and going its own way.

In By Twosies Twosies

That’s enough theology for now. Let’s get back to Joseph Barnard Lynch.

In 1887 Lynch went to Philadelphia to consult a doctor about his arthritis, and it seems that at some point during this trip he was exposed to Holiness preachers.

The movement had yet to reach Chincoteague due to its isolation, and it must have struck Lynch like a thunderbolt. He was already dissatisfied with the Methodist Episcopal Church and its focus on social justice, and this seemed like the perfect counter to that. Holiness began slowly creeping into the Bible study sessions he led every Thursday at the Goodwill Independent Church.

Lynch’s particular brand of Holiness seemed to check off almost every doctrinal error mainstream Methodists were worried about. He believed in instantaneous Sanctification, entire Sanctification, and marital purity.

At first his neighbors took little notice, though they may have raised a few eyebrows when he told his class that he had experienced an instantaneous and entire Sanctification.

The Lord has been with me and I am sanctified. I have died and have been born again, and I know that I shall be saved, and whatever befalls I shall be happy while I live on Earth.

What did raise eyebrows was when Lynch stopped living with his wife Charlotte and began living with Sarah Collins. It turns out Lynch also believed that those who were called to the ministry had to preach two by two, following the example of Mark 6:7 (“And he called unto him the twelve, and began to send them forth by two and two; and gave them power over unclean spirits.”). More than that, he believed those pairs had to form a complete dyad of man and woman.

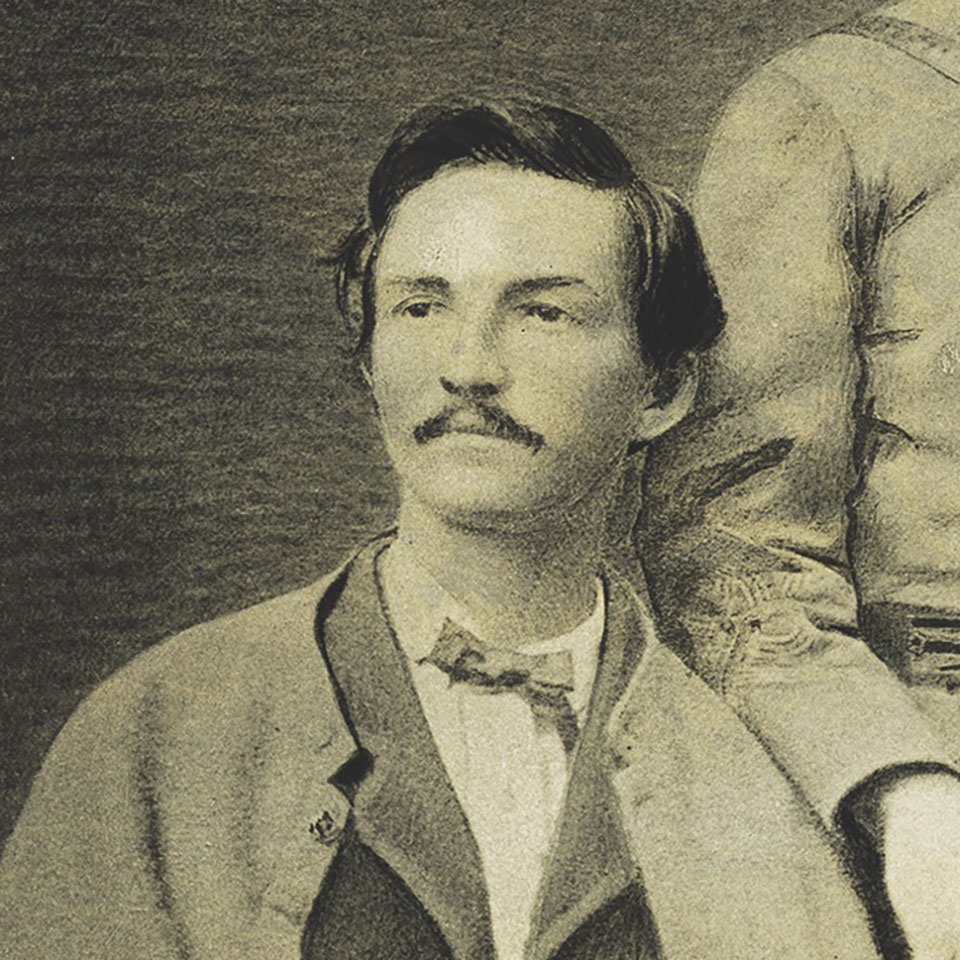

Sarah Collins (or “Sister Sadie” as she came to be known) had been one of the first woman on the island to be Sanctified, so it made sense to Lynch that she should be his watchmate, partner, and co-minister. It wasn’t a problem that they lived together, partly because they were incapable of committing sin and partly because their marriages to the unsanctified were not valid.

(It’s not clear whether they having sex. Church documents insist their relationship was purely a spiritual one. Even if it wasn’t, Joseph’s wife Charlotte and Sadie’s husband John seemed fine with the entire arrangement and they’re the only two people whose opinion matters here.)

All Lynch’s non-Sanctified neighbors could see was that one of their prominent citizens had abandoned his wife of twenty-something years to take up with a married woman some thirty years his junior. (They also weren’t too happy about the idea of a woman being a preacher, either, but we’ll leave that for another day.)

This was final straw for the Methodist Episcopal Church, which was already mad that Lynch had been “stealing souls” from their congregation. Minister George Jones began attacking Lynch and his followers from the pulpit. Im return, Lynch and his followers petitioned Bishop Edward Andrews in Wilmington, demanding to be sent a new minister, a “true man of god” this time. The bishop responded by stripping the petitioners of their leadership positions in the Methodist Episcopal Church, and forbidding them to use the Goodwill Independent Church for their meetings.

On Sunday, February 14, 1892 Sadie Collins confronted Jones before his afternoon service, presenting him with written notification of their intention to withdraw from the church. (It’s weird to me that anyone would think they have to ask permission to leave the church instead of just, you know, leaving, but whatever.) They asked Jones for an immediate response, but he ignored them, so during the service Lynch rose from his seat and raised the matter again. When he too was ignored, the Sanctified rose up as one and walked out of the service. (Later local magistrates threatened to arrest them for interrupting a public worship service, but ultimately did not file charges.)

Not long after the Sanctified petitioners formed their own church. Joseph Lynch was installed as minister, deacon, and general manager. Sadie Collins was installed as deaconess and “chief female supervisor.” Both were given full authorization to preach and lay on hands. James Workman was also selected to be a minister at the time.

They called themselves Christ’s Sanctified Holy Church. Others called them “Lynchites” or “Lynchettes,” but mostly they were called “the Sanctified Band.”

(The “Sanctified Band” was actually a dismissive nickname that was applied to any number of groups that believed in Sanctification theology, but it seems to have really stuck to this particular group of believers for some reason.)

We should probably talk about what the Sanctified Band believed, as laid out by Lynch and Collins in 1893’s The Doctrines and Discipline of Christ’s Sanctified Holy Church.

We’ve already mentioned that they believed in instantaneous Sanctification, and entire Sanctification.

We are sanctified, thank the Lord. We cannot sin. We are of the kingdom of Heaven. We are in his body and heart and the Sanctified cannot sin.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 9 Sep 1894

To prep the way for one’s Sanctification, it was necessary for one to forswear:

- fancy clothing and ornamentation

- spirits and tobacco

- profaning the sabbath day

- taking the name of the Lord in vain

- worldly songs and literature “not to the glory of God”

- membership in any secret societies, orders, or clubs (boo)

Upon becoming Sanctified, a man should take a woman as his “watchmate” and vice versa. Your heart would tell you who was the one. But beware!

The woman must not be your wife, for who of you is married in God? You are joined to a woman by the laws of your land, unless you are joined to her in the eyes of God you must not watch with her.

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 9 Sep 1894

Watchmates should sit up all night at least once a week, drinking water, studying the Bible and praising the glory of God. Sanctified People were also expected to spend time in service to the Lord and his Sanctified Holy Church. Other than that, there was “no creed but Christ, no law but love, and no guide but the Bible.” (Collins & Hagan)

Well, mostly. There were a couple of other small things, like only Sanctified People could go to heaven. Or marry and have children. And if you were married before being Sanctified you had to separate from your wife.

They also held the rather progressive idea that women and men had the same rights. So, thumbs up there at least!

At first the Sanctified People had no church, but they weren’t picky about where they worshipped. They held meetings wherever they could, even outside if they had to. Eventually they began holding services in an old warehouse that had been used to store fishing nets, which was heated only by two large tin stoves. It was humble, but it was home.

During services one member (usually Lynch or Collins) would give a sermon and lead the group in prayer. Afterward any of the Sanctified People could preach, testify, or sing as the spirit moved them (though Lynch liked to keep an eye on the clock and tended to cut speakers off after about fifteen minutes). Eventually this would turn into a party, as everyone sang, clapped, danced until they dropped from exhaustion. At least one service was so joyous it never officially ended; parishioners just sort of trickled out of the church, still singing the glories of God all the way home.

Members of established churches rolled their eyes at these “wild frantics” but they proved popular. The original Sanctified Band had only been about sixty people, but in two years it doubled in size. They sent out missionaries to preach up and down the Delmarva Peninsula, even into African-American communities, and established churches in Frankford and Williamsville, Delaware.

Drove Those Animals Crazy Crazies

So, here’s what the official History of Christ’s Sanctified Holy Church by Harry J. Collins, Jr. and Floyd L. Hagan, Sr. has to say about what happened next.

…by the end of 1894 the Sanctified People had become restless. In an effort to spread their Word, they began to travel throughout the Eastern Shore of Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. Their dedication to the movement empowered the people to leave behind their oystering, clamming, and fishing jobs on Chincoteague, along with their homes and all of their possessions. They journeyed through unfamiliar areas, rarely charting a course in advance and not knowing what they would encounter. They traveled, as God told Abraham, “To get thee out of thy country, and from thy kindred and from thy father’s house until a land that I will shew thee.” (Genesis 12:1)

History of Christ’s Sanctified Holy Church

This passage is, uh, broadly accurate but leaves a lot of important little details out. So let’s dive into that, shall we?

The Sanctified Band tried to keep to themselves, but that didn’t stop others from getting up in their business. Methodist and Baptist ministers attacked them from the pulpit. The learned would attempt to challenge Lynch and Collins to theological debates, only to get their hats handed to them each time. The less high-minded settled for physically abusing Lynch instead, though he never gave them the satisfaction of responding.

Because they were unable and unwilling to understand the Sanctified’s belief system, they developed a narrative that Lynch was some sort of con man and his followers brainless sheep. It was even rumored that Lynch faked miracles, specifically that he “walked on water” by balancing on wooden boards just below the surface. (The other half of this rumor was that once a prankster removed the boards and Lynch fell into the bay and almost drowned. Never happened.)

What really set most outsiders on edge was the idea that a man could leave his wife and take up with a new watchmate. They could not grasp that this was primarily a spiritual endeavor, and so of course rumors began to spread that the Sanctified practiced free love and were constantly swapping partners. That led to the worry that the Sanctified would eventually come for their non-Sanctified womenfolk.

The official church history is very adamant that there was no hanky-panky going on, but let’s be frank — there had to be a little hanky-panky going on. If you tell most men, “Set aside your wife and take up with your spirit wife,” their first thought is going to be, “Great! Let’s go to spirit pound town.” The idea that this was rampant and that the entire church was just some sort of big key party is almost certainly mistaken, though.

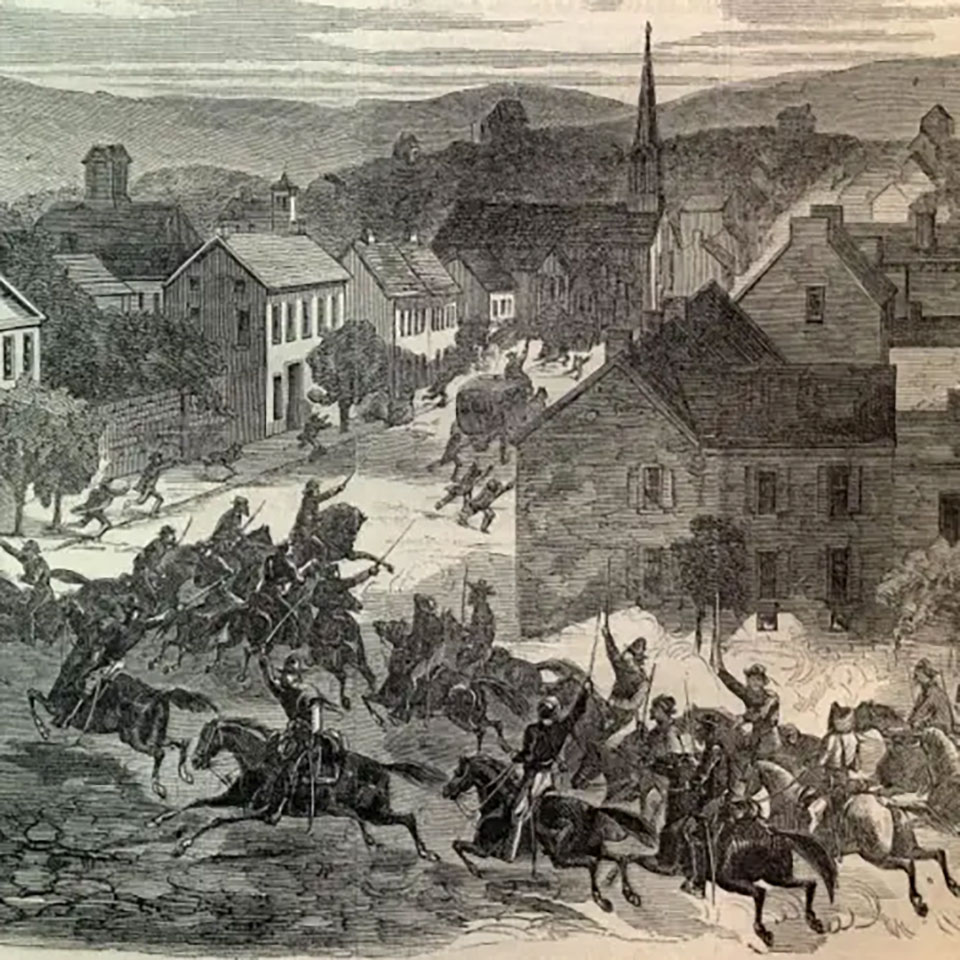

As the free love rumors spread, opposition to the Sanctified Band intensified. Which is the polite way of saying in the summer of 1894 angry mobs burned down the two churches in Delaware. And that was hardly going to be the worst of it.

On September 1, a “picked-up gang” of eleven Chunkers decided to go up the island and make trouble. Just for the record, they were Daniel Beebe, William Bloxon, Arthur Burns, John Daisey, Solomon Daisey, Lewis Danger, Frederick Fresh, Oliver Jester, William Mumford, Henry Savage, and Irving S. Sturgis. Their goal was to “get a move on” Minister James Workman, who, it was rumored, was having his way with every woman on the island.

They went “hullaballoing” up Main Street and arrived at the Sanctified church around 11:30 PM. Workman was nowhere to be found, so they took out their rage on the church, smashing its windows and starting a small fire (which did not catch). They began knocking on the doors of Sanctified People, looking for someone they could beat up, then threw rocks through the windows when no one answered. Eventually they drew their pistols, let out a wild whoop, and fired shots into the air as they rode back south.

Sanctified Person Aaron Thomas Bowden was sleeping next to an open window so he could get some fresh air. One of the bullets struck him in the head, blowing his brains all over the bed. His wife, who had been sleeping next to him, had no idea what was going on until she lit a lantern and saw everything covered in gore.

In the cold light of day, the Chunkers of Chincoteague looked at what they had done and decided there was only one thing they could do…

…blame it all on the Sanctified Band.

Rumors began to spread that Bowden had been killed by the Sanctified for refusing to share his wife and daughters with them, and fingered his brother John as the likely shooter. Mobs of locals with shotguns began combing the island looking for Lynch, threatening to shoot or hang him if they caught him.

Eventually the true culprits were identified, and one-eyed oysterman Irving Sturgis fingered as the man who had fired the fatal shot. They were arrested… but never went to trial. As far as local authorities were concerned it was a justified homicide.

[T]he wonder is that the lewd and lascivious habits of the Sanctified crowd practiced by them under the guise of religion has not led to bloodshed before.

The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction

No, the “wholesome-hearted, intelligent people of Chincoteague” knew who was really to blame: Joseph Barnard Lynch, a “devil with a forked tail that swept from Chincoteague Light to the tower of Assateague, threatening to extinguish the moral light of the whole island.” Aided, of course, by Sister Sadie, the doe-eyed temptress who lured in men with crude sexuality so Lynch could seal the deal with animal magnetism.

A parade of distinguished Chincoteague citizens went to the authorities to swear out complaints, real and imagined, against the Sanctified. On September 18, 1894 Lynch, Collins, and several others were indicted for “lewd and lascivious practices,” a blanket charge which apparently included practicing free love, luring young women into sex slavery, letting women be preachers, and trying to convert African-Americans. The actual charge was something like “creating a nuisance through corrupt preaching.”

The defense attorney tried to get the case thrown out on the grounds that it wasn’t actually a criminal offense under any known law, but his motion to dismiss was overruled.

The Sanctified Band seemed to welcome the trial, which began in early November. They sailed their boats over from Chincoteague and up Folly Creek, then camped out en masse outside the Accomack County Courthouse to attend the trial. Large crowds of locals dropped by just to gawk at their religious ceremonies.

The scene inside the courtroom was just as packed and chaotic. Everyone wanted to get a glimpse of the freak show. Prosecution witnesses were histrionic, making Christ’s Sanctified Holy Church out to be a polyamorous sex cult, whose every doctrine was a mortal affront to god and country. For their part the Sanctified were forthright and honest about everything they said and believed. Indeed, the Commonwealth prosecutor seemed quite surprised with the ease he was able to drag confessions from Lynch and Collins that watchmates frequently hugged each other and gave each other “the kiss of peace.”

The prosecution, the press, and the public were obsessed with all the hugging and kissing. One gets the sense that they couldn’t wrap their minds around the concept of non-sexual intimacy. They certainly couldn’t comprehend that the Sanctified felt not the least bit of shame about such contact, what with being free from sin and all. At least it gave us this funny exchange with Sanctified witness Ebe Merritt:

PROSECUTOR: You began to work with Miss Arlina?

MERRITT: Yes sir, studying the word of God.

PROSECUTOR: She had no husband to shoot you. Do you kiss Arlina and put your arms around her?

MERRITT: When I feel like it; just as I would any other lady when I meet her.

PROSECUTOR: Do you kiss and hug every lady you meet?

MERRITT: If I want.

PROSECUTOR: Well, you’re a privileged man, I must say.

Honestly, the Sanctified’s defense was basically that not only were their actions perfectly legal, they weren’t anyone else’s damn business. From a modern perspective it’s hard to argue with that.

It’s a pity the jury didn’t share that opinion. They deliberated for less than an hour before returning the following verdicts:

- Joseph B, Lynch, guilty, 8 months imprisonment or a fine of $250.

- William J. Chandler, guilty, 6 months imprisonment or a fine of $150.

- Sadie E. Collins, guilty, 4 months imprisonment or a fine of $100.

- John Collins, not guilty on account of being feeble-minded.

No one did hard time. Lynch, Collins, and Chandler were set free as they appealed the judgment. Though they didn’t plan on sticking around to see how that would turn out.

Build Him an Arky Arky

A month after the judgement Lynch and Collins could not be found anywhere on Chincoteague. In late November they quietly sold their property at fire sale prices and in early December they sailed away on the Annie Homan, a 60′ sloop. Other members of the sect followed suit, and eighteen months later the Sanctified Band had completely vanished from Chincoteague. They even sold their church to the Methodists, who sold it to someone else who turned it back into a warehouse, and then it burned down.

For the next decade the Sanctified Band were nomads living in float houses, or as outsiders called them, “arks.” These were basically crude houseboats made by attaching prefab frame houses to flat-bottomed barges. Partitions divided the interior into a small kitchen, a dining room, and a large communal sleeping space; but could be rearranged to create a floating tabernacle for worship ceremonies. There were about twenty people to an ark and very little privacy, but no one seemed to mind.

The name “arks” suggested to the press that the Sanctified were worried about some sort of imminent deluge. All this tells me is that the press hadn’t been reading their Bible — no more water, the fire next time. In any case, the Sanctified Band was not concerned about an imminent apocalypse.

The arks had no motive power of their own, so they were towed from place to place by sailboats. At a painfully slow pace, I should add. At least that gave the Sanctified People plenty of time to fish, which became their primary source of income.

Their primary pursuit, of course, was spreading the good news. They would sail to a new town, moor their boats, open ’em up, and start a revival. Sometimes they received a warm reception. Usually they didn’t. When trouble started they would just weigh anchor and move on down the coast.

First, they sailed north to preach in Baltimore, and then down to Washington where Lynch preached from the steps of the Capitol. Alas, neither Charm City nor the New Babylon were receptive to their message so they kept working down the coast. Eventually they made their way to North Carolina, and that’s when the trouble really started.

The Sanctified Band was met with hostility wherever they set up shop. One suspects most of this was driven by their antipathy to established religions, and their constant statements that unsanctified ministers were leading their flocks down the primrose path. The ministers seem to have responded in kind.

In spite of the attacks, or possibly because of them, people were drawn to the Sanctified and their message. They drew large crowds of the curious wherever they met and made numerous converts. One occasion, a sawmill had to be shut down for the day because all the workers abandoned their posts to go down to the revival.

In response elites grew increasingly hysterical, and eventually made the Sanctified the center of a full-blown moral panic. They were accused of threatening the lives of ministers. They were portrayed as polygamists and polyandrists. Lynch was a scheming villain who used a “horse-tamer’s drug” to befuddle potential converts, who were exclusively drawn from “the lowest class from whom no lasting impression will be made.” Collins was a doe-eyed temptress. The rest of the group were kidnappers who snatched wives and daughters and killed babies.

It wasn’t long before potential converts were outnumbered by haters. And while the people of Chincoteague weren’t exactly nice to the Sanctified, they were at least hesitant to harm those who had once been their friends and neighbors. The people of North Carolina had no such compunctions.

In Beaufort, they were “disinvited” from the town by a local vigilance committee.

In March 1896, Sadie Collins was arrested for performing marriages but the charges had to be dropped because she was, after all, a licensed minister.

In August 1896 a large group of the Sanctified sailed up the Chowan River and tied up near Cannon Ferry. They had some small successes but also encountered intense hostility from the locals. Purportedly, the trouble began when the Sanctified converted two young women, Matilda Petty and Lizzie Bell Pearsnall, whose fathers objected and decided to take them back by force. At midnight on August 21 the encampment was surrounded by a mob of 153 people, armed with rifles, pistols, bowie knives and swords. They began crowding the arks and shouting demands, only to be ordered back. After a while the Sanctified decided to put some distance between themselves and the mob, weighed anchor, and began to reposition themselves about 50 yards offshore. The mob thought they were trying to flee and opened fire, sending volley after volley after volley into the arks. The shooting only stopped at 2:00 AM when they ran out of bullets. One Sanctified woman was killed and several men were injured. Just as in Chincoteague, everyone was firmly on the mob’s side, even though there was no evidence the Sanctified had done anything wrong. “The fact that they are earnest is no proof that they are honest,” the newspapers tutted. They also reported that the Sanctified had returned fire, which they absolutely had not, and never bothered to publish corrections. The leaders of the mob were identified and arrested, but on September 4 the charges were thrown out because the warrants had been “drawn up wrong.” The administrative costs of the abortive prosecution, some $50 in total, was imposed on the Sanctified Band. Prosecutors began drawing up new warrants but the Sanctified could see where this was all heading. They left town before the new trial started.

On July 17, 1897 locals who attended a meeting of the Sanctified in Camden were shot at by ambushers as they tried to return home. Six days later the Sanctified were meeting at a local believer’s home when parties unknown began firing into the building. Fortunately no one was seriously injured except for an old mule tied up outside. The Sanctified decided to cut their losses and moved on.

That was the reception they got everywhere from Corolla to Southport. The only bright spot was that state authorities refused to sanction the mob violence. Governor Elias Carr and Attorney General Frank Osborne would not prosecute the Sanctified Band without concrete evidence of wrongdoing, which could not be provided for the simple reason that they weren’t do anything wrong.

They didn’t lift a finger against the mob either, mind you. So the Sanctified kept moving south.

They seem to have skipped South Carolina, perhaps realizing they would get an even worse reception there. In 1898 they set up shop outside of Savannah, Georgia selling salvation and eel pies to hungry troops headed to Cuba during the Spanish-American War. In 1899 they were in Palatka, Florida where they rented out an old resort hotel to hold their services.

And that’s where, at least, one part of this story ends.

On September 3, 1900 Joseph Barnard Lynch passed away in Fernandina Beach. I would like to say he had a quiet and dignified death, but it was attributed to food poisoning so it was probably rather messy.

Everything Was Fine and Dandy Dandy

Sadie Collins took over after Lynch’s death. She continued to be a nomad, but a train nomad instead of a boat nomad, traveling the country by rail and making converts from Kissimmee to California. Thanks to her able leadership the Sanctified were eventually able to overcome local hostility and settle down. They even returned to Chincoteague to reestablish their church back where it all started.

Christ’s Sanctified Holy Church is still around, though it is neither a large sect nor a particularly influential one. It can still boast more than a thousand believers spread all over the southeastern United States, which is nothing to sneeze at. That’s more people than listen to this podcast.

No one should ever have to suffer the sort of persecution the Sanctified faced for decades. Alas, that’s just what we do in this country: low-information moral panic first, nuanced understanding later. When will we learn to approach others with an open mind and treat their beliefs with respect?

Probably never. Now excuse me, I have to go finish writing an episode about a weirdo UFO cult. Toodles!

Connections

One has to wonder what they put in the water over there in Vineland, NJ. Not only did it host the first Holiness camp meeting in this episode, it was also the home of the Training School for Backward and Feeble-Minded Girls, where Henry Herbert Goddard worked to establish a scientific foundation for the eugenics movement (“Common Clay”); and also home to the Dinshah Health Society, which believes in the pseudo-science of color healing (“Normalating”).

Accomack County, Virginia is not only the location of Chincoteague Island, it was also once the home of Francis Mackemie, who was arrested for preaching without a license by New York governor (and possible transvestite) Lord Cornbury (“Universally Detested”).

You often seen cult members showing up en masse to the trial of their leader, partly as a show of support and partly as a form of intimidation. Most notably this technique was used by the United Nuwaubian Nation of Moors during the trial of their leader Dwight York for 197 charges of child abuse and other related offenses (“Space is the Place”).

I first encountered the story of the Sanctified Band while researching the Koreshan Unity (“We Live Inside”). Specifically, they’re mentioned in friend-of-the-podcast Lyn Millner’s The Allure of Immortality: An American Cult, a Florida Swamp, and a Renegade Prophet. You should go read her book right now.

Sources

- Alexander, Estrelda Y. Black Fire: One Hundred Years of African American Pentecostalism. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2011.

- Ayers, Edward L. The Promise of the New South: Life After Reconstruction. Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Collins, Harry J. and Hagan, Floyd L. Sr. History of Christ’s Sanctified Holy Church. Theo Davis Sons, 2005.

- Dieter, Melvin E. The Holiness Revival of the Nineteenth Century (Second Edition). Scarecrow Press, 1996.

- Mariner, Kirk. Once Upon an Island: The History of Chincoteague. Miona Publications, 2003.

- Millner, Lyn. The Allure of Immortality: An American Cult, a Florida Swamp, and a Renegade Prophet. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2015.

- Perrow, E.C. “Songs and Rhymes from the South.” The Journal of American Folklore, Volume 26, Number 100 (April-June, 1913).

- Piepkorn, Arthur Karl. Profiles in Belief: The Religious Bodies of the United States and Canada, Volume III: Holiness and Pentecostal. Harper & Row, 1979.

- Sanders, Cheryl Jeanne. Saints in Exile: The Holiness-Pentecostal Experience in African-American Religion and Culture. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Synan, Vinson. The Holiness-Pentecostal Movement in the United States. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1971.

- “Census of Religious Bodies in United States.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 256 (March 1948).

- “General Survey.” The Progressive Thinker, 15 Sep 1900.

- “An engagement which the Sanctified Band’s leader failed to keep.” Charlotte (NC) Observer, 23 May 1893.

- “Ministers going to hell.” Evening Journal, 11 Nov 1893.

- “Santificationists in trouble.” News Journal, 18 Nov 1893.

- Dawe, G. Grosvenor. “The Sanctified!” Democratic Messenger, 9 Jun 1894.

- “A strange religion.” Sacramento Bee, 23 Jul 1894.

- “A religious fraud.” Albany (OR) Weekly Herald, 2 Aug 1894.

- “Assassinated in bed.” News Journal, 4 Sep 1894.

- “Killed by a mob.” Philadelphia Times, 4 Sep 1894.

- “Shot while sleeping.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 5 Sep 1894.

- “The killing of A.T. Bowden.” Baltimore Sun, 6 Sep 1894.

- “The Chincoteague murder.” Daily Republican, 7 Sep 1894.

- “Chincoteague Chunkers.” News Journal, 7 Sep 1894.

- “Story without a parallel.” Virginian-Pilot, 8 Sep 1894.

- “Very strange.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 9 Sep 1894.

- “High priest Lynch in jail.” Alexandria Gazette, 18 Sep 1894.

- “Two-by-twos go to jail.” Wilmington (DE) News Journal, 18 Sep 1894.

- “Call themselves Sanctified.” Times-Herald, 19 Sep 1894.

- “Wife against husband.” The Witness, 27 Sep 1894.

- “J. Lynch released.” Richmond Dispatch, 30 Sep 1894.

- “Released.” Alexandria Gazette, 1 Oct 1894.

- “Sanctified Band.” Richmond Dispatch, 3 Nov 1894.

- “Lynch gang on trial.” Richmond Dispatch, 3 Nov 1894.

- “The Sanctified chief.” Richmond Dispatch, 4 Nov 1894.

- “The Sanctified Band.” Alexandria Gazette, 5 Nov 1894.

- “Virginia affairs.” Baltimore Sun, 5 Nov 1894.

- “The Sanctified Band.” Alexandria Gazette, 6 Nov 1894.

- “Sanctified in cells.” Richmond Dispatch, 6 Nov 1894.

- “Sanctified Band.” Richmond Dispatch, 20 Nov 1894.

- “Sanctified Band breaks up.” Alexandria Gazette, 3 Dec 1894.

- “Sanctified again make trouble. Wilmington Morning News, 28 Jun 1895.

- “They swap wives.” Anaconda Standard, 28 Sep 1895.

- Democratic Messenger. 16 Nov 1895.

- “Sanctified Band.” Washington Evening Times, 9 Dec 1895.

- “Not capable of sin.” Raleigh News and Observer, 26 Jul 1896.

- “The Sanctified Band.” Wilmington Morning Star, 23 Aug 1896.

- “Attacked the saints.” Norfolk Virginian, 23 Aug 1896.

- “Joe Lynch!” Democratic Messenger, 29 Aug 1896.

- “The Sanctified Band of North Carolina.” New York World, 30 Aug 1896.

- “The trial of those who attacked the Sanctified Band.” Edenton (NC) Fisherman and Farmer, 4 Sep 1896.

- Roxboro (NC) Courier, 30 Sep 1896.

- “Four arks and a new Noah.” Raleigh News and Observer, 11 Oct 1896.

- “The Sanctified Band.” Washington (NC) Progress, 17 Nov 1896.

- “A new religious crusade.” Washington (NC) Progress, 17 Nov 1896.

- “Should be suppressed.” Daily Concord Standard, 23 Jan 1897.

- “The new religious crusade.” Washington Gazette, 11 Feb 1897.

- “Oregon news.” Washington Progress, 16 Jun 1897.

- “Sanctification Band at Beaufort.” Raleigh News and Observer, 20 Jun 1897.

- “Husband had a vision.” North Carolinian, 29 Jul 1897.

- “The Sanctified Band.” Wadesboro Messenger and Intelligencer, 5 Aug 1896.

- “The Sanctification band.” Wilmington Messenger, 11 Aug 1897.

- “Evils of Sanctified Band.” Asheville Daily Citizen, 11 Aug 1897.

- “Unable to procure evidence against Lynchites.” Greensboro Patriot, 25 Aug 1897.

- “That Sanctified Band.” Wilmington Evening Journal, 7 Sep 1897.

- “The Sanctification Band.” Wilmington Messenger, 28 Sep 1897.

- “Lynchites to try Lee’s men.” Savannah Morning News, 22 Oct 1898.

- “Change wives semi-monthly.” Wilmington Evening Journal, 24 Apr 1900.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: