The Best Exotic Marigold Gospel

for one messiah, this is just the beginning of an exotic adventure

There have probably been more words written about Jesus of Nazareth than any other person in history, and for all that only the smallest part of his life has been documented.

The Gospels of John and Mark start with thirty-year-old Jesus being baptized by his cousin John the Baptist. The Gospel of Matthew starts with Jesus’s birth and the flight to Egypt, then skips ahead twenty-nine years to the baptism. The Gospel of Luke goes into a little more detail, with the full-blown nativity story, an anecdote from Jesus’s bris, tween Jesus debating rabbis in the temple… and then skipping ahead a mere eighteen years to Jesus’s baptism.

So there’s a fairly large gap in Jesus’s life. At least Luke seems pretty sure nothing terribly interesting happened during this period:

Then he went back with [his parents] to Nazareth, and continued to be under their authority; his mother treasured up all these things in her heart. As Jesus grew he advanced in wisdom and in favor with God and men.

Luke 2:51-52

Luke is only one of four Evangelists, though. John left future writers a bit of wiggle room:

There is much else that Jesus did. If it were all to be recorded in detail, I suppose the world could not hold the books that would be written.

John 7:25

If John were writing today he could easily update “would be” to “were.”

As anyone who’s ever watched a fandom develop on the Internet can tell you, people hate blank spots and will fill them with all sorts of crazy stories. That’s just as true for Jesus as it is for the Winchester Brothers and the Crystal Gems. It should not surprise you to realize that our ancestors had a lot of ideas about what Jesus was doing during those missing years.

They didn’t have AO3 in olden times, so Jesus fan-fiction took the form of alternative gospels. These are less sober reflections about how the Son of Man developed his philosophy, and more, “the adventures of Jesus when he was a boy!” Which is to say, a lot like the adventures he had as an adult, except that he was living at home with his parents; his girlfriend was still M.M. but a different one with red hair; and he was best friends with Judas Iscariot until the terrible lab accident that made Judas lose his hair and turn evil.

I’m joking, but then again, I’m not. These apocryphal gospels are chock full of bad history, off-kilter theology, dragons, and Jesus casting spells like a 20th-level magic-user. They’re buck wild.

Centuries laters we are still driven to complete the biography of Jesus, though attempts by modern theologians and scholars tend to be a bit more grounded and realistic. For instance, post-baptism Jesus has some very complex ideas for someone who’s just had a spiritual awakening, so it has been hypothesized that he spent some time studying theology with the Pharisees, Sadducees, or Essenes. It’s still only a guess, but it’s an educated guess.

Of course, there was still plenty of wild speculation.

In 19th Century it was widely believed that Jesus had traveled to India to study religion. This flowed directly from several contemporary trends: a secular reexamination of the Bible driven by the rediscovery of Gnostic texts; a universalist desire to create a shared lineage for all cultures and religions; and an Orientalist obsession with India as the “cradle of civilization.”

It should not surprise you to learn that there’s absolutely no evidence for this idea. And why would it? We barely have evidence that Jesus himself existed outside of the Bible and the writing of Josephus.

That didn’t stop proponents of the “Jesus in India” idea from grasping for straws. They claimed that Jesus’s lifestyle was like that of a Hindu ascetic; they noted doctrinal similarities between Christianity and Buddhism, and structural similarities between Roman Catholicism and Tibetan Buddhism; they advanced spurious etymologies showing that the Hebrew “messiah” has the same linguistic roots as the Sanskrit “matreiya”; they rooted out vague references to Jesus in historical texts; they pointed to Asian folk tales about Jesus as proof that he had traveled there.

These are pretty weak, even as straws go.

Jesus’s nomadic lifestyle resembles that of a Hindu ascetic, but it clearly has roots in the tradition of nomadic Jewish prophets and judges.

Any doctrinal similarities between Christianity and Buddhism are insignificant, the sort of basic moral instruction common to religions that emphasize the spiritual over the material.

Catholicism and Tibetan Buddhism have superficial similarities, but their differences are so pronounced that the Jesuits once assumed that lamaseries had been created by Satan as a parody. European etymologies of non-European languages are often fanciful at best. Mentions of Jesus do appear in historical texts, but those texts are never contemporary accounts and they do not claim that Jesus traveled beyond the borders of Judea.

Folk tales about Jesus are also easy to explain. Christianity was not exactly unknown in Asia. Tradition holds that the Apostle Thomas went to India shortly after the Ascension; Manichaean and Nestorian Christianity prospered in Central Asia for centuries; and Catholic missionaries had been traveling to China since the days of Marco Polo. A common missionary tactic is to retcon Christian themes into local legends, explaining any number of “Jesus slept here” tales.

If the idea that Jesus had studied in India was ever going to move from the fringe to the mainstream, its proponents would have to find much stronger evidence.

Or, you know, make some up.

The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ (1894)

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Notovich was born on August 13, 1858. He was Jewish by birth, though his family converted to the Russian Orthodox faith when he was a young child. Not because they were particularly religious, mind you; they were a cosmopolitan middle class family and they really just wanted to opt out of pogroms and persecution.

As a young man Notovich studied at the University of St. Petersburg, and then moved to Paris to work as a journalist. After the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, Notovich took a job as a foreign correspondent for the newspaper Novoye Vremya. He spent most of the 1880s tramping across the Near East and Central Asia. reporting on the political situation in the Ottoman Empire, Afghanistan, and India.

In October 1887 those travels took Notovich to Ladakh, a region in the foothills of the western Himalayas that is sometimes called “Little Tibet.” While visiting the city of Kargil, he made a detour to the nearby Mulbekh Monastery to interview the lama. Apparently Notovich was a fearless conversationalist, because he dove right into one of the topics you’re not supposed to raise in polite conversation: religion.

The lama had nothing nice to say about Muslims, but he was fine with Christians because Buddhism and Christianity were the same religion, after all. That confused Notovich, and he asked the lama what he meant. The lama explained that hundreds of years ago the Buddha had incarnated himself as Issa, the best of the sons of men, who had studied Buddhism in Tibet and traveled to the West to teach the sutras, only to be tortured and killed by those who feared him. Notovich was still confused, so the lama made it easy for him.

Jesus. He was talking about Jesus.

That got Notovich’s attention. He asked if the lama had any proof for this incredible claim. Alas, no. The gompas in Lhasa had thousands upon thousands of scrolls devoted to the life and teachings of Issa, but there were only a few such scrolls outside Tibet. Mulbekh was not one of the gompas so honored.

Notovich became obsessed with the lama’s story. For the next several months, the Russian visited monasteries all over Ladakh but could not find a single scrap of paper that said anything about Issa.

He got his first nibble some 25 miles outside of Leh at the Hemis Monastery. The gompa there did have some works about Issa, translations of Pali originals from the libraries of Lhasa. Unfortunately, they were buried somewhere in the cluttered library. The lama promised he would search for them, but it was clear that he wasn’t going to make it his top priority. Notovich left Hemis without his proof, but gave the lama an alarm clock, a watch, and a thermometer to thank him for his assistance — and maybe to encourage him to go digging in the stacks in his free time.

Then, a stroke of luck!

Bad luck, that is. A few days later Notovich fell from a horse and broke his leg. His companions took him back to Hemis to convalesce, and while he was laid up the lama finally found what the Russian had been looking for. He strolled into Notovich’s room and plopped down “two large bound volumes with leaves yellowed by time.” For a whole day the lama read the books aloud in Tibetan, while Notovich’s companions translated and the journalist frantically took down notes in shorthand.

When Notovich returned to Europe a few years later, he took those notes with him and began to revise them. He edited them down for brevity, rearranged them into chronological order, and formatted them into a traditional Biblical chapter and verse format. He was excited. This, he thought, was a discovery that would rock the world.

Or maybe not.

In Ukraine, Notovich showed his manuscript to Metropolitan Platon of Kiev. The Metropolitan agreed that Notovich had made an important discovery, but told him government censors would make sure it was never published.

In Rome several cardinals told Notovich his discovery was insignificant and unbelievable, and if he published it he would make many powerful enemies. Then they changed tactics and offered to generously recompense him if he turned over his notes and forgot about Issa. Notovich refused.

Then Notovich brought his work to biblical scholar Ernest Renan, who had published a controversial biography of Jesus in the 1860s. Renan was intrigued, offered to present Notovich’s findings to the French Academy, and then died before he could make good on that promise.

It took a few years, but eventually Notovich found a publisher. In 1894 he released La vie inconnue de Jesus Christ, or, The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ.

The first half of the book is a travelogue recounting Notovich’s adventures in India and Tibet and building to the discovery of the Issa manuscripts in Hemis. The second half is his translation of the book he had found, “The Life of Saint Issa, The Best of the Sons of Men.”

The book claims to be an account written by merchants freshly returned from Palestine. They had witnessed the Crucifixion, recognized Jesus as the prophet they had known as “Issa,” and decided to write down his story.

Issa is a precocious child born in Israel who is wise and charismatic from birth. By the time he’s a tween he is already being hailed as the Messiah and attracting disciples, but when his parents try to marry him off to the daughter of a rich merchant he flees Israel and hitches a ride on a caravan heading east.

Eventually Issa arrives in Odissa, where the Brahmins recognize his wisdom and accept him as a brother. He spends six years studying the vedas in Jagannath, Rajagriha, and Benares. Then he starts making trouble. First he reads the vedas to lower castes, which is forbidden. Then he denies the existence of the Hindu gods, says the vedas are fiction, and calls for all temples to be destroyed. Needless to say, this doesn’t sit well with the Brahmins, who try to have him killed.

Issa flees to Tibet, where the lamas recognize his wisdom and accept him as a brother. He spends six years studying the sutras. Then he starts making trouble, denying the doctrine of reincarnation and claiming miracles are a sham. Needless to say, this doesn’t sit well with the lamas, who try to have him killed.

Issa flees to Persia, where the Zoroastrian magi recognize his wisdom and accept him as a brother. Then he starts making trouble, mocking sun worship as idolatry. Needless to say, and I know this is a surprise, this doesn’t sit well with the magi, who try to have him killed.

Issa flees to Israel. At this point, the story becomes a condensed version of the Gospels, as Issa builds his ministry, upsets the authorities, and is crucified for his trouble. Interestingly, the blame for the Crucifixion is placed firmly on the shoulders of Pontius Pilate, who famously washes his hands of the whole matter in the four Gospels. The end.

People loved it. The book was a huge success, going through eight printings in its first year. It even became an international bestseller, topping the charts in five different countries. At one point three different translations were simultaneously vying for attention in American bookshops.

You know who didn’t like it? Theologians. And they brought up some really good points.

The Life of Saint Issa claims to have been written only a few years after the Crucifixion. That would make it the earliest known Christian literature, decades older than the Pauline epistles and the Gospel of Mark. There’s a problem with that: the ending of the story features Issa’s apostles leaving Israel to spread the good news, which would have still been a few years in the future. The story also seems to have been influenced from the other Gospels, which had yet to be written.

Those aren’t the only anachronisms. Issa studies at temples and holy sites that wouldn’t exist for centuries. He explicitly denies the Trimurti, a trinitarian union of Brahma the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer, even though that doctrine had yet to be formulated.

The unknown writer also has some weird ideas about religion. Jains worship the wrong god; Brahmins seem fine with teaching the vedas to an outcaste foreigner; Buddhists are inaccurately presented as monotheists. Even the Christianity is strangely un-Christian, reduced to a faith of mealy-mouthed middle-of-the-road platitudes. There are no miracles in the book; no virgin birth, no wedding feast at Cana, no faith healing or exorcisms, no raising of Lazarus, no Resurrection. Issa even decries belief in miracles as something that “destroys the innate simplicity of man and his childlike purity.”

And finally, there’s the simple fact that text of The Life of Saint Issa doesn’t support the central hypothesis of The Unknown Life, that Christianity and Buddhism have a common source. While Issa does study Buddhism, he explicitly rejects its core tenets and does not incorporate any of its teachings into his preaching. Which raises the question of why, exactly, Buddhists would have bothered to preserve it in the first place.

Frankly, the book seems less like a genuine text about early Christianity and more like the ramblings of an agnostic 19th Century dilettante with only a superficial knowledge of the things he was writing about. Someone who’d written down what little he remembered of the Gospels from Sunday school, and then gone through the text to remove Judaeo-Christian concepts like “God” and replace them with quasi-Orientalist terms like “the Eternal Being.” Someone suspiciously similar to Nikolai Notovich.

Admittedly there could be perfectly innocent explanations for all of this. Anachronisms could have snuck in over the centuries as the book was copied and recopied. Other eccentricities in the text could be the result of a centuries long game of telephone, as the book had started out in Pali and passed through four or five different languages before finally seeing print in French.

Fortunately, there was a simple way to check. All someone had to do was go to the Hemis Monastery, find the book, and compare it to Notovich’s published version. Easy peasy.

I think you know where this is going.

In early 1894, the year The Unknown Life was published, an English tourist decided to travel to Hemis to see the original book for herself. The confused monks had no idea what she was talking about. They had no idea who “Issa” was, they certainly didn’t have any books about him, and no Russian had ever visited there.

In October of that year she was followed by Anglican missionary E. Ahmad Shah. The monks had the exact same response. They even let Shah into the gompa to look around, where he noticed that the library was filled with scrolls and not bound books like the ones Notovich claimed to have seen.

In May 1895, Professor J. Archibald Douglas made another attempt to find the original source. He got the exact same response. Notovich had never been there. He had not given gifts to the lama (who did not even know what a thermometer was). He had not been allowed to copy any books (which didn’t matter anyway because the book he supposedly copied didn’t exist). The only reason they knew about Issa at all was because curiosity seekers kept asking about him.

Two decades later in 1914, Italian explorer Fillipo di Fillippi visited Hemis. There was only one small change to the story he got. The lamas did say they’d heard of Issa and could share a few tales, but those tales had clearly been lifted directly from The Unknown Life.

Maybe they were barking up the wrong tree. There were supposedly thousands of scrolls about Issa somewhere in Lhasa, so why not search there instead? In 1927, the Reverend Gergan Tharchan did just that, and could not find a single scrap of paper about Issa. In 1953, a group of Bengali Christians and Moravian missionaries conducted an exhaustive search and also found nothing. A third search in 1980 by filmmakers Richard and Janet Bock also turned up nothing, and they even got an on-the-record statement from the Dalai Lama that the writings had never existed.

When the writings failed to materialize, debunkers turned the spotlight back on Notovich and they did not like what they found.

Large portions of his travelogue were plagiarized from other sources. Many of the little details about the places he visited were wrong, like location, and distance, and which temples belonged to which sect. He said he visited a gompa that had been burned down. He claimed to have seen festivals that weren’t held in the years he was traveling. His translator, described as a “simple Kashmiri shikari,” seemed improbably able to translate some pretty abstract philosophical ideas. No one in Leh remembered Notovich breaking his leg, though a Dr. Karl Marx (no relation) remembered him having a pretty bad toothache.

The conclusion was inescapable: Notovich was a liar and had made the whole thing up. Or, if you were feeling generous, maybe he had compiled local folk tales and tried to pass them off as ancient documents. Or, if you were feeling really generous, Notovich was the victim of an elaborate hoax pulled by the lamas of Hemis for some reason.

Notovich added a postscript to later editions of The Unknown Life responding to some of these criticisms. His main counter-argument was that the lamas in Hemis were denying the existence of The Life of Saint Issa because they wanted to protect the book from Westerners who would steal it from them and take it back to Europe. (That didn’t explain why they had shown it to him in the first place, but whatever.) Tellingly, though, he spends most of the postscript trying to obfuscate the matter by arguing facts that were not in dispute — like that he had visited Leh, or that just because the text was unknown didn’t necessarily mean it was fake.

In one sense, Notovich succeeded. No serious theologian takes The Unknown Life seriously, but thousands of religious wing-nuts still take it as, uh, the gospel truth.

In another sense, he dug his own grave. He returned to Russia the year after the book was published and was quickly arrested on unpublished charges, probably blasphemy. He was briefly exiled to Siberia but was paroled so that he could work in France as a spy. He was a terrible spy, though, and was back in Russia after only a few months. Sometime during World War I he just vanished, and no one ever heard from him again.

The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ (1911)

Once a crazy idea gets out into the wild, though, it’s almost impossible to contain it again. Subsequent fringe-dwellers would keep returning to and expanding on the works of Notovich.

A perfect example would be Levi Dowling’s 1911 The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ, which presents a comprehensive version of the life of Jesus drawing from the Gospels, widely accepted extra-canonical sources, and Gnostic literature along with more modern apocrypha, like the Theosophical works of Helena Blavatsky and Notovich’s Unknown Life.

Dowling does Notovich one better, though: his Jesus travels to India, Tibet, China, Persia, Assyria, Greece and Egypt and studies the ancient ways in each of these places. Dowling also goes into exhausting detail about Jesus’s adventures; The Aquarian Gospel is longer than most copies of the entire New Testament.

Now, if you wanted to argue through the Aquarian Gospel point by point, well, there’s plenty to pick at. Jesus visits places that doesn’t exist yet, meets people like Mencius who had been dead for hundreds of years, he attends a “Council of Sages” which are basically the Ascended Masters of Theosophy. The good news is, you don’t have to! Because all you need to write off The Aquarian Gospel is right there on the title page

The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ, the Philosophical and Practical Basis of the Religion of the Aquarian Age of the World and of the Church Universal, Transcribed from the Book of God’s Remembrances, Known as the Akashic Records, by Levi

If you’re not familiar with the Akashic Records, they’re a concept from Theosophy. They’re basically a giant psychic encyclopedia of everything that has ever happened or will ever happen that can accessed by someone who has achieved the proper state of attunement to the Universal Mind of the Infinite One.

Which is the long way of say they don’t exist, which means everything Levi Dowling didn’t steal from other writers is just made up. (Most of what he stole from other writers is just made up, too.)

Altai-Himalaya (1929)

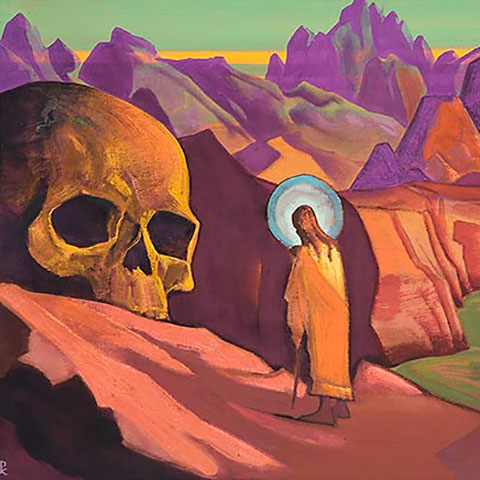

The idea that Jesus studied in India probably had no greater advocate than Russian painter and mystic Nicholas Roerich. Roerich was obsessed with Theosophy and drew artistic inspiration from the religious art of Russia, India, and Tibet. It’s only natural that he came under the sway of Notovich and Dowling.

Throughout the 1920s Roerich made several trips that took him all over Asia, from India to Mongolia. His primary goal was to make pilgrimages to holy sites and find new inspiration for his artwork, and also to unite Central Asia in the “Sacred Union of the East,” an ill-conceived utopian government that was somehow both Buddhist and Marxist. And of course, he also found the time to try and track down the truth about Issa.

He didn’t find a damn thing because, once again, the Issa stories are made up. Roerich didn’t let his failure shake his faith. His knew in his heart that the truth about Issa was being deliberately hidden, either by the Buddhist establishment or by Christian missionaries.

Of course, if that were the case, it wouldn’t explain why he seemed to be hearing Issa stories from every local. Roerich seemed to think these were tales that had come to the east with Manichaeans and Nestorians centuries before. But that wouldn’t explain why most of those stories seemed to be quoted from Notovich’s Unknown Life or Dowling’s Aquarian Gospel. And I don’t mean similar to, or paraphrased from. I mean quoted directly.

I suppose it’s possible that the good people of Ladakh were just in tune with the Universal Mind and drawing from the Akashic Record. But it’s far more likely that Roerich was just putting words in other people’s mouths.

He did find a few new Issa stories, and they’re… just weird.

As Issa went on his wanderings, he saw a great head. On the road lay a dead human head. Issa thought that the great head belonged to a great man. And Issa decided to do good and to resurrect this great head. And the head covered itself with skin. And the eyes filled themselves. And there grew a great body and the blood flowed. And the heart was filled. And the mighty giant rose and thanked Issa that he resurrected him for usefulness to humankind.

Nicholas Roerich, Altai-Himalaya

I don’t know what the point of that story is. What’s the moral here? Is there some other story about the giant that we’re missing? But despite its incomprehensibility it also feels genuine. If I had to make a guess, it’s probably a example of Jesus being inserted into an already-existing local legend that has nothing to do with him.

It’s also worth keeping in mind that Roerich thought that if the locals had heard of Jesus, that was proof that the Issa legends were true. After all, it was entirely unlikely that people in remote villages would have heard about the most written and talked about individual in history at some point in the previous two thousand years. (I hope you can hear the sarcasm in my voice.)

While Roerich’s “investigation” was a bust, it did make one thing abundantly clear. The people who believed in the story of Issa weren’t going to let a little thing like “facts” get in the way.

Jesus in India (1908)

As the stories of Notovich and Dowling took their place at the fringes of religious belief, a second set of stories about Jesus’s travels to India began to make the rounds.

Other writers claimed that Jesus had visited India later in his life, or rather, during his afterlife. The idea was that he had survived the Crucifixion, either through a medical miracle or supernatural trickery, and fled from Israel to India to live out the rest of his life in peace.

The proponents of this theory pointed to the Gospel of Matthew, which, notably, doesn’t actually say that Jesus was going to die, just that:

The Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the bowels of the earth.

Matthew 12:40

They could also point to this passage in the Qu’ran:

They boasted, “We killed the Messiah, Jesus, son of Mary, the messenger of Allah.” But they neither killed nor crucified him — it was only made to appear so. Even those who argue for this ‘crucifixion’ are in doubt. They have no knowledge whatsoever — only assumptions. They certainly did not kill him. Rather, Allah raised him up to Himself. And Allah is Almighty, All-Wise.

Surah An-Nisa, 4:157-158

There were also recently discovered Gnostic writings where Jesus tricks another person, usually Simon of Cyrene, into taking his place on the cross. Or the Jesus on the cross is just his earthly substance, which has already separated from his divine substance. Or the Jesus on the cross is entirely illusionary, a phantasmal force created by Jesus’s God-powers.

So, the idea that Jesus had survived the Crucifixion was already out there.

Few writers, though, took this as far as Mirzā Ghulām Ahmad, founder of the Ahmadiyya sect of Islam. Ahmad’s musings on the topic were posthumously published as Jesus in India in 1908.

In Ahmad’s telling, Jesus did suffer on the cross but did not die, only fell into a coma. His grieving disciples accidentally buried him alive, and three days later he woke up and rolled back the stone covering his tomb. He quickly realized he could no longer stay in Israel, so he changed his name to “Yuz Asaf” and moved to Kashmir. The native Kashmiris, it turns out, were actually the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel and so he preached to them for a while. Eventually he settled down, got married, and moved to a cute little house on Khanyar Street in Srinagar to raise his kids. Then he died at the ripe old age of 120.

At least one part of Ahmad’s story tracks. There is a tomb in Srinagar, the Roza Bal, where one “Yuz Asaf” is buried. However, it’s not quite clear who Yuz Asaf actually was. The historical record is mum on the topic, and local legends that claim he’s Jesus are based solely on the similarities between the names “Yuz” and “Issa.” That’s a pretty big stretch.

Fortunately, it’s pretty easy to pick apart Ahmad’s arguments. Among other things he extensively quotes from Notovich, whose book is not only a complete fiction but also presents a version of the Passion where Christ actually dies on the cross. Ahmad tries to argue that these inconsistencies can be hand-waved away because Notovich based his work on Buddhist writings, and Buddhists are sloppy copyists who are always revising things to make themselves look better. Dude, you can’t have it both ways — either these books are accurate, or they’re not. And they’re definitely not.

Of course, just because there’s no proof doesn’t mean that people won’t believe it. That’s the entire basis of faith, after all.

Hindu Swamis (1922-Present)

One group that keeps repeating the “Jesus in India” lie is Hindu swamis. Over the years the story has been revived by Swami Abhedanada of the Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, Paramahansa Yogananda of the Self-Realization Fellowship, Swami Sivananda of the Divine Life Society, and Sathya Sai Baba of the Sathya Sai Organization.

What these swamis have in common is that they all made serious attempts to reach Western audiences. Unfortunately Western audiences are almost completely ignorant of Indian culture, but they do know Jesus. So if you can somehow start with Jesus and then move from him to Hinduism, well, you’ve got a convert.

To cement the idea that Jesus was deeply tied to Hinduism, the swamis swiped the basic structure of Notovich’s Unknown Life — that there was a secret text hidden in a Tibetan monastery that few had seen, revealing that Jesus had actually studied in India before becoming a prophet. They had to excise all the bits where Jesus calls Hinduism a false religion and gets chased out of dodge, of course, along with the bits where he goes and studies other religions. Then, to deepen Jesus’s ties to India, they welded on Ahmad’s Jesus in India story that he had survived the Crucifixion and retired to Kashmir.

I’m not entirely sure why they thought this was necessary. By the 20th Century comparative religion was a whole thing. They could have just talked about Jesus, and then segued into how his ideas were both similar and different from those of Hinduism. There’s no need to insert a fake story into the equation, but they did.

As usual, none of them were able to produce the original documents because they just don’t exist. Maybe that was part of the appeal, that by hearing the stories their students were being let into a secret so dangerous it couldn’t be written down.

Jesus Died in Kashmir (1976) and Jesus Lived in India (1983)

Over time, the New Age movement took the Hindu philosophies that had been faddish in the 1960s and incorporated them into its weird pseudo-sacred melange of religious practices severed from their original contexts and meanings. The Issa myths came along with the ride, and saw a brief resurgence of popularity in the late 1970s.

In 1976, Spanish writer Andres Faber-Kaiser paraphrased Ahmad’s teachings as Jesus Died in Kashmir. Faber-Kaiser didn’t actually add anything new to the discussion, but he did revive the idea for a new generation of kooks.

One of those new kooks was German writer Holger Kersten. Kersten, like many others before him, was captivated by Notovich’s Unknown Life and decided to travel to India and Pakistan to see if he could find the Hemis manuscript and discover the real truth for himself. He didn’t find the manuscript, because it doesn’t exist,

In 1983 Kersten wrote Jesus Lived in India, which combines Notovich, Dowling and Ahmad into a single semi-coherent story. On top of that, he adds another layer of wackiness. You see, Kersten seems to think Kashmir is the Holy Land, which he bases on a couple of similar-sounding place names. So the majority of action in the Gospels actually took place in Kashmir, only to be moved to Israel by later historians who found that inconvenient. Never mind thousands of years of history and archaeology.

Kersten’s major accomplishments are twofold. First, he summarized the writings of every theologian, historian, and scholar who addressed the Issa myth, and then he selectively quoted from them to make it seem like they were agreeing with it instead of debunking it. Second, he exhaustively listed every shred of “evidence” that supposedly proved the Hemis manuscript had existed. So let’s cover some of the new counter-arguments he brought to bear.

- There was a “certain Mrs. Hervey” who, according to Kersten, first saw the manuscript in 1853 and related the tale in her book The Adventures of a Lady in Tartary, Thibet, China and Kashmir. The only problem is no one’s been able to find a copy of that book in the last forty years to double-check Kersten’s assertion.

- Kersten also says that Lady Henrietta Sands Merrick saw the manuscript and wrote about it in her her 1931 book In The World’s Attic. Except Merrick only mentioned the legends in passing without commenting on their veracity, and never says that she’d seen the manuscript. Merrick was also American and therefore not a Lady. (Well, capital-L lady. You know what I mean.)

- There was music teacher Elizabeth Gétaz Caspari, who claimed that on a 1939 trip to Hemis the monks spontaneously approached her with a book and said it proved Jesus had lived in India. Except Caspari couldn’t read Tibetan, so she had to take them for their word. She did take a photo of the open book, but the photo is so out-of-focus that the book can’t be read.

- There’s also the Natha Namvali, a Hindu sutra that purportedly recounts the Issa legend. Except that as far as anyone can tell, the Natha Namvali only seems to exist in the form of the short quotation in Kersten’s book. The only mentions of the sutra on the Internet are all in relation to Kersten and the Issa myth, and no one has actually managed to locate a copy. Probably because it’s secret, you see.

Kersten’s problem, of course, is that he’s building his house on sand, basing his arguments on already debunked stories and just pretending that they hadn’t been debunked. He doesn’t have anything resembling convincing or conclusive proof, though that hasn’t stopped him from milking the concept for diminishing returns and two more books.

Conclusion

And that, more or less, brings us up to date.

As we review what we’ve learned today, things don’t look good.

We’ve got one group of people who have been repeating the same baseless claims non-stop for 128 years. We’ve got another group of people who uncritically believe those claims just because it feels right and plays into their preconceptions. And neither group has bothered to update or adapt these claims, in spite of an overwhelming mountain of contrary evidence.

That’s not great. So look on the bright side: 99% of the world doesn’t believe this story is true. That should be cause for celebration. So have a sip of champagne.

It might help you forget that the remaining 1% loud, obnoxious, and everywhere on the Internet.

Connections

Dowling’s Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ was later plagiarized by Noble Drew Ali, the founder of the Moorish Science Temple (“Space is the Place”).

If the name Mirza Ghulam Ahmad sounds familiar to you, well, it should. In 1902 he challenged Scottish faith healer and self-proclaimed messiah John Alexander Dowie (“Marching to Shibboleth”) to a “prayer duel” where each would pray to their God for the other’s death. In more recent years his teachings were appropriated by the United Nuwaubian Nation of Moors (“Space is the Place”).

Sources

- Ahmad, Mirza Ghulam. Jesus in India. Punjab: Islam International Publications, 2016.

- de Camp, L. Sprague. The Fringe of the Unknown. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1983.

- Dowling, Levi H. The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ. London: L.N. Fowler & Co., 1920.

- Ehrman, Bart D. Forged: Writing in the Name of God — Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are. New York: Harper Collins, 2011.

- Fader, H. Louis. The Issa Tale That Will not Die: Nicholas Notovich and His Fraudulent Gospel. Lanham, MD: University Press of Amereica, 2003.

- Goodspeed, Edgar J. Strange New Gospels. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1931.

- Hale, Edward Everett. “The Unknown Life of Christ.” The North American Review, Volume 158, Number 450 (May 1894).

- Hanson, James M. “Was Jesus a Buddhist?” Buddhist-Christian Studies, Volume 25 (2005).

- Houston, G.W. “Jesus and His Missionaries in Tibet.” The Tibet Journal, Volume 16, Number 4 (Winter 1991).

- Joseph, Simon T. “Jesus in India? Transgressing Social and Religious Boundaries.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Volume 80, Number 1 (March 2012).

- Kersten, Holger. Jesus Lived in India. New York: Penguin Books, 1981.

- Lewis, James R. Legitimating New Religions. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2003.

- Notovich, Nicholas. The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ. Chicago: Progressive Thinker Publishing House, 1907.

- O’Collins, Gerald and Kendall, Daniel. “On Reissuing Venturini.” Gregorianum, Volume 75, Number 2 (1994).

- Roerich, Nicholas. Altai-Himalaya. New York: Frederick, 1929.

- Prophet, Elizabeth Clare. The Lost Years of Jesus. Corwin Springs, MT: Summit University Press, 1984.

- Rama, Swami. Living with the Himalayan Masters. Honesdale, PA: Himalayan Institute Press, 1978.

- The Koran. New York: Penguin Books, 1956.

- “The Glass Mirror.” Tomb of Jesus India. https://www.tombofjesus.info/2018/12/the-glass-mirror/ Accessed 2/15/2022.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: