520%

if something seems too good to be true, it probably is

William Franklin Miller needed money.

We all need money, but Miller needed it more than most. The 21-year-old had a wife and an infant child, both of them sickly and frail and in desperate need of expensive medications.

To make matters worse, Miller had few options when it came to earning money. He considered himself to be above blue-collar work, but he also had no aptitude for white-collar work. He had previously worked as an office boy and a clerk and he had been terrible at both of those jobs. Also he was lazy and entitled.

He had only one option remaining: finance.

Miller didn’t have the funds necessary to buy real stocks, so he starting hanging around the bucket shops of Brooklyn. A “bucket shop,” if you aren’t familiar with the concept, is a specialized betting parlor where wagers are placed on stocks and commodities. Nothing actually changes hands other than money. If you ever did an exercise in economics class where you pretended to buy and sell penny stocks, it’s the same sort thing only with real money involved. (Also, the reason you didn’t use real money in that exercise is that bucket shops are illegal as hell these days.)

Miller quickly proved himself as inept at stock trading as he was at everything else, losing all of his money in short order. Somehow he remained hopeful, convinced he just needed a hot tip on the right stock to turn his luck around. Maybe more cash on hand so he could hedge his bets and eventually buy his way into the real stock market. He didn’t have any money, though. Neither did his friends or family. No one legit would lend to him, because they knew he was no good for it. Going to a loan shark was out of the question too, because he rather fancied his kneecaps.

Then he had a genius idea.

On March 16th, 1898 Miller made a proposal to the Christian Endeavor Society of the Tompkins Avenue Congregational Church. If his fellow Bible study students gave him $10 each he would use it to speculate on the stock market. In return he would indemnify their deposit against any potential loss, and pay them a 10% weekly dividend.

At the time, an annual return on investment of 6% was considered pretty good. Municipal bonds paid out about 2.5%; the New York Central Railroad paid 4%; the Pennsylvania Rail Road, the good ol’ Pennsy, paid 6%; and Pullman, a real blue-chip stock, paid 8% per year.

William F. Miller was offering 10% per week.

If you deposited $10 and pocketed the $1 dividend every week, at the end of the year you would have $52, a 520% annual rate of return on your investment. If you deposited the dividend, then through the magic of compound interest you would have $1,420. If Miller somehow lost all of his money you would still have your original $10.

That’s clearly insane. To reach those target numbers, Miller would have to do more than meet a 520% annual return on his investment portfolio — he would have to beat it, or there would be nothing left for him to skim off the top. That would make him the greatest investor in history, and if he was the greatest investor in history why was he pitching to Bible study students in a church basement? No serious investor would have given Miller’s proposal a second thought.

These weren’t serious investors. These were nobodies in a church basement, and Miller’s proposal sounded pretty good to them. Maybe they were primed by the setting to think that Miller was a good man. Maybe they were fooled by the small round numbers. Maybe they were just blinded by greed. No one can say for sure.

What we can say is that Oscar Bergstrom was the first to make a deposit. He plunked down his $10, and got an official-looking receipt from Miller. The other members of the Christian Endeavor Society quickly followed suit.

To be fair to Miller, he actually thought he could pull it off. Like every gambler, he had a system to beat the house. I mean, if it didn’t work, they wouldn’t call it a system, right? He couldn’t lose!

He lost almost all of it.

At the end of the week he had just enough money left to pay out the dividends he owed, and had to pray no one wanted their guaranteed deposit returned.

Then something funny happened. Nobody wanted their deposit back. They didn’t even want their dividends. They wanted to deposit more money. And their friends wanted in, too.

Miller did some quick calculations in his head and realized he had a good thing going. He didn’t have to make any actual investments. He could just the use new deposits to pay out dividends to everyone who wanted them, and pocket the rest. As long as no one withdrew their guaranteed deposits, he could keep this up for a weeks and no one would be the wiser. Heck, if he could find more depositors he could keep this up for months. Maybe even years.

This, my friends is a classic scam. And one that works like a charm.

The Boy Napoleon of Finance

Let’s skip ahead to February 1899.

William F. Miller has become a runaway success. Not as a day trader, mind you. He did try at least once, but had only managed to turn $1,000 of depositor funds into $994.64 of red ink. No, he was the greatest flim-flam artist Brooklyn had ever seen.

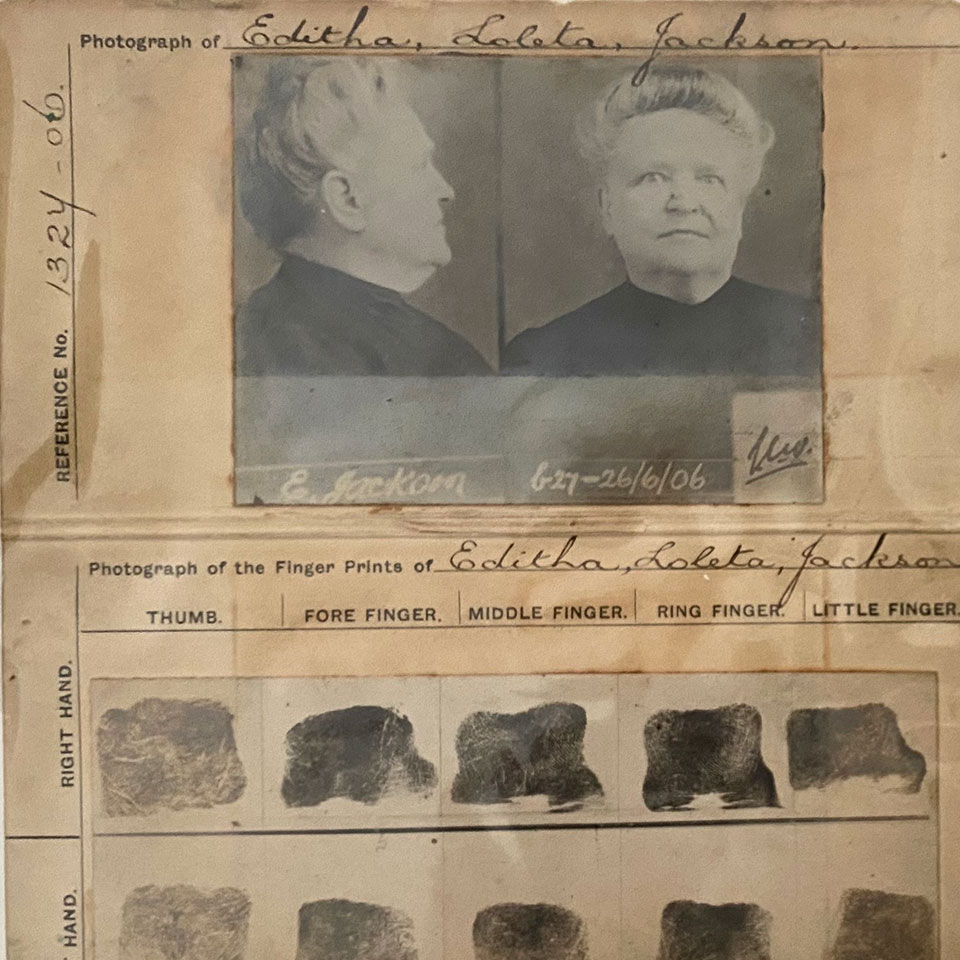

Miller used to tramp from door to door, paying dividends out of the cash in his wallet and handwriting deposit tickets. Now he had a boy to do that for him. A couple dozen boys and clerks, actually, all working out of a two-story tenement at 144 Floyd Street. The headquarters of “The Franklin Syndicate.”

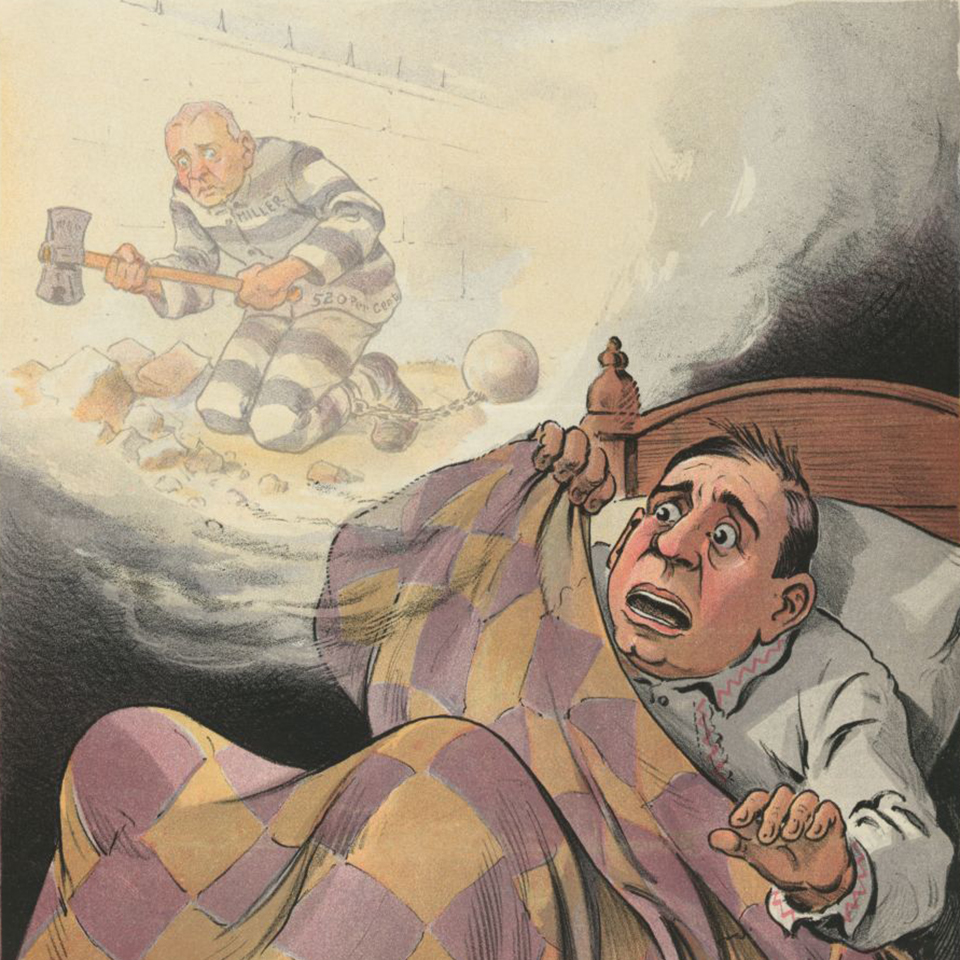

They called him “The Boy Napoleon of Finance.” Given how Napoleon ended up, it was a surprisingly apt nickname. (Spoilers, I guess.)

Every day the sidewalk in front of the Franklin Syndicate’s office was packed with depositors who took their dividend and redeposited it, usually adding everything they’d managed to save in the previous week. They walked away waving a green deposit slip, their ticket to wealth beyond their wildest dreams. Every week there were more and more of them.

But never enough.

The weakness of this sort of scheme is that it requires constant growth, and the moment growth starts to slow down it becomes vulnerable. Sooner rather than later the amount of money coming in will be less than the amount of money you are obligated to pay out in dividends. Once you miss a dividend, depositors will attempt to withdraw their funds. That creates a liquidity crisis, because you’ve been keeping the overage for yourself and you’re not disposed to share. And that’s assuming you haven’t already spent it. The magic of compound interest makes it even worse. If your marks had taken the dividend every week, you’d be on the hook for $10. But they’ve been reinvesting it, and now you’re on the hook for hundreds if not thousands of dollars.

To pull in more marks, Miller invested $32,000 into an ambitious advertising campaign. Personal ads for the Franklin Syndicate ran in newspapers across the country. Potential investors were deluged with circulars and newsletters and prospectuses without end.

If you knew anything at all about finance, Miller’s pitch sounded ridiculous. If you were an idiot it all sounded empowering, like he was trying to pass on the secrets of the rich to the little guy:

Your $10 or more, according to the number of shares you take, is invested for you each week in stocks or wheat, according to what inside information we have. Ten dollars is a very small sum, considering that you get $52 a year and upward, paid you weekly, which is far better than you can do elsewhere. This may look impossible to you; but you know there must be a way where one can double their money in a short time or else there would be no Jay Gould, Vanderbilt, or Flower syndicates who have made their fortunes in Wall Street, starting with nothing…

My ambition is to make the Franklin Syndicate one of the largest and strongest syndicates operating in Wall Street, which will enable us to manipulate stocks, put them up or down as we desire, and which will make our profits five times more than they are now…

We also guarantee you against loss, there being absolutely no risk of losing, as we depend entirely on inside information.

Who could possibly pass up an annual return of 520%, which might in the very near future become an annual return of 2600%? Even if you thought Miller was full of Shinola, you might just plunk down $10 on the off chance that he wasn’t!

Deposits started arriving in the mail from places as far-flung as Ottawa and Ohio. There was so much mail the post office had to establish a special delivery just for 144 Floyd Street. Franklin Syndicate employees had nowhere to put all that money, so they dumped it in boxes, stuffed it into drawers, or just left it lying around in stacks. Some days they were literally knee-deep in cash.

Miller felt overwhelmed and wasn’t sure what to do next.

So he brought in a partner. Sources are unsure who Edward Schlesinger was, or even if Schlesinger was his real name. Was he finance bro? An accountant? A bucket shop bookie? A con artist? Whatever he was, he took one look at Miller’s operation and realized it was amateur hour. Deposits were crammed into a big safe at the back of the office. Deposits were being paid out of petty cash. No one was doing any sort of accounting, and that was worrying. The most important part of any con is knowing when to cut and run, and without careful accounting Miller had no way of knowing when the Syndicate was about to go belly up.

Schlesinger put a stop to that. Every day after the close of business, he and Miller would sit down and count out the day’s take. They would re-stock the office safe with enough money to cover the anticipated dividend payments and withdrawals for the following day. Then Schlesinger took 33% of the profits, and Miller deposited the rest into his personal account at a real bank down the street.

For the first time in months the Syndicate was running smoothly.

At the end of summer, Schlesinger’s ledgers showed that the Syndicate’s growth had started to slow down. So the Syndicate hired a full-time PR guy, Cecil Leslie, to hype their services. They expanded into the Boston market by opening a branch in Charlestown under the management of Louis Powers. They mailed their newsletters to ever more remote prospects, some of them on the West Coast. Existing depositors were offered a 5% commission on new deposits from referrals, creating a sort of multi-level marketing scheme.

And it worked. For a while.

Couldn’t Escape If I Wanted To

The wheels started to come off in September.

Miller was the treasurer of the Tompkins Avenue Congregational Church’s Paris Excursion Club, which offered a first class package tour of the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris for the budget price of $100. How could this be possible? Easy! The club’s money was deposited with the Franklin Syndicate. Remember what I said earlier about the magic of compound interest? When the Club tried to withdraw funds so it could start paying travel agents, Miller didn’t have thousands of dollars in cash to spare. The excursion was off, and Miller was kicked out of the church.

Syndicate ad buyer Rudy Guenther knew that something was wrong. Miller was stressed out and overwhelmed. Schlesinger had already checked out, only showing up at the end of the day to take his cut. Guenther suggested to his bosses that the Syndicate needed legal advice, and he knew just the man for the job: Colonel Robert Ammon.

Ammon was a real character. The son of a well-to-do family from Birmingham, PA (now Pittsburgh’s South Side neighborhood), he graduated from Western University of Pennsylvania (now Pitt) and then decided to he would rather party rather than work. He was disowned by his family, hit the skids, and eventually wound up working as a brakeman on the Pittsburgh, Fort Wayne, and Chicago Railroad.

When the Great Railroad Strike started in 1877, Bob Ammon had just been elected the head of the Trainman’s Union. When the strikes and riots brought the trains to a stop, he briefly became the most powerful man in Pennsylvania. Then the boys realized Bob Ammon didn’t care about safer working conditions, shorter hours, or better pay. All Bob Ammon cared about was power. He was kicked out of the union right before everything went to hell.

After the strike ended, Ammon moved to California and became a nativist politician pushing an anti-Chinese agenda. He ran a gold mine in Montana for a few months, and then drained its accounts and split town. Eventually he relocated to New York, earned a law degree, and became a fixer, helping white-collar criminals cover their tracks. He was very, very good at it. Over the years he’d helped robber barons, swindlers, and other assorted scoundrels escape justice. Crime reporter Arthur Train once described him thusly…

He could talk a police inspector or a city magistrate into a state of vacuous credulity, and needless to say he was to his clients as a god knowing both good and evil, as well as how to eschew the one and avoid the other.

Arthur Train, True Stories of Crime from the District Attorney’s Office

When Miller and Schlesinger came to Bob Ammon for advice, he grasped their problem immediately and proposed a solution. He told his new clients he would incorporate the Franklin Syndicate. Then Miller would get the Syndicate’s depositors to exchange their deposit slips for stock in the new company. The cash value of the stock certificates issued would be nominally equivalent to the previous deposits, with one important difference: they wouldn’t be guaranteed. That way when the liquidity crisis eventually hit, the Syndicate could just fold and call it a day.

Miller’s next circular announced the upcoming incorporation and asked all depositors to mail in their slips. He promised that the Syndicate would continue to do business as usual, that everyone would continue to receive their dividends. He even suggested the value of the stock would increase, supplementing those dividends with capital gains. It would have worked, if he hadn’t also shot himself in the foot:

After December 2nd… I shall open no new accounts for less than $50. All accounts which I now have of less than $50 will have to deposit sufficient to make their account $50, or they will not be taken into the new corporation.

Miller was trying to squeeze every last drop of cash out of his existing small depositors. The risk was that those small depositors would just cash out entirely and take the whole scheme down with them.

One small depositor in Media, PA wasn’t sure what this all meant. He wrote to the financial newsletter “On Change” asking for advice. Editor E.L Blake did a little poking around and discovered that the stock exchanges in New York or Chicago had never heard of William F. Miller. No brokerage house had an account in his name. Several financial institutions, including the Hide & Leather Bank and the Broadway Bank, had even closed Miller’s accounts after learning about the dividends he was offering. Blake reached the only possible conclusion: the Franklin Syndicate was a scam. He published an editorial warning investors to stay far, far away from William F. Miller.

Blake’s editorial was only the beginning. Other newspapers, like the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and the Boston Globe, started poking around the Syndicate. The American Banker’s Association launched its own investigation. So did the police, though frankly they had no idea how to handle white-collar crimes.

The situation in Boston, where the Syndicate had only recently opened its branch office, started to look extremely shaky. Miller and Ammon made a special trip to Beantown and hurled $50,000 in a sack at a Boston Post editor to convince him that the Syndicate was legit. Then they pulled the same stunt at police headquarters. To calm the public they offered to allow depositors to withdraw their funds without advance notice, for one day only. The resulting run on the bank cost the Syndicate some $33,000, but it helped restore public confidence in the scheme.

Ammon could see that the Syndicate’s days were numbered, and it was time for one big final score. He told Miller to wire all of his depositors, tell them he was about to close a big deal, and that they should send in everything they could spare to get a piece of the action. Miller sent the telegrams. Collect, of course.

It worked — boy, did it work. On Friday, November 17th the crowd of depositors at 144 Floyd Street was so enormous that the building’s stoop collapsed under their combined weight. Thankfully no one was hurt. Miller continued to take deposits through the chaos, sitting on the remnants of the top step stamping his signature on receipts and tossing the deposits over his shoulder to an army of waiting clerks inside the front door. That day the Syndicate brought in $81,000 in new investments — and paid out $36,000 in dividends.

Newspaper reporters peppered Miller with questions as he worked, and he dodged them as artfully as he could. Yes, the Syndicate traded mostly in commodities like coal and iron. No, he would not say which brokerages it used. When asked why the Hide & Leather Bank had dropped him, he said the bank couldn’t handle the sheer volume of postal orders he brought in every day. When asked if that situation might change now that the postmaster had shut down the special delivery due to suspicions of mail fraud, Miller could do nothing but glare and refer all future questions to his lawyer.

At least the syndicate’s press agent, Cecil Leslie, was more than happy to talk to reporters.

I know Miller is connected with a big senatorial clique in Washington. You see, at the beginning of the Spanish-American War holders of Cuban bonds employed Mr. Miller to go to Washington in their interests to try and preserve the integrity of these bonds. While there Mr. Miller got in with these Senators and they formed some kind of a ring by which Miller gets his tips and is enabled to pay these enormous dividends.

None of this was true, and I’m not sure why Leslie thought it would help to implicate his boss in insider trading, graft, and corruption.

On Wednesday, November 21st Miller was arrested. It turns out that when Syndicate depositors asked him about the “On Change” article, Miller had implied that E.L. Blake was a blackmailer trying to ruin the company. Word made its way back to Blake, who filed a libel suit against Miller. The business came to a screeching halt as Miller was frogmarched down to court for a bail hearing and forced to fork over a $5,000 bond.

While Miller’s bail was being set, reporters discovered an interesting fact. Despite the fact that the Franklin Syndicate had been mailing out stock certificates for weeks, it had actually only been incorporated in New Jersey on the previous day. The company had no directors or executives, and only paid-in capital to the tune of $1,000 — significantly less than the $4,000,000 Miller had previously claimed. It was also not licensed to operate as a bank or brokerage… or outside of the borders of New Jersey.

Bob Ammon was questioned about the incorporation, and his response didn’t help at all.

Well, it’s none of the public’s goddamned business.

The newspapers made this information public on November 22nd, which caused a run on the Syndicate on November 23rd. When depositors descended on Floyd Street, though, Miller was nowhere to be found. No, he was busy hustling over to Bob Ammon’s office with a burlap sack full of ill-gotten gains. He was surprised to find his business partner was already there, and that he and Ammon had already come up with a plan.

SCHLESINGER: The jig’s up.

AMMON: Billy, I think you’ll have to make a run for it. The best thing for you is to go to Canada.

Schlesinger was heading off to Europe. Ammon had a man who could take Miller up to Montreal, where he could low until the heat died down.

In the meantime, he should transfer all the Franklin Syndicate’s funds over to Ammon so the lawyer could hide them from authorities. Miller forked over everything he had on him: $30,500 in bills and $10,000 in checks and postal orders. Then they all went down to Wells Fargo, where Miller still had an account under a fake name. He transferred $100,000 in cash to Ammon, along with $40,000 in government bonds. Later, Miller’s father-in-law signed over $65,000 of New York Central Railroad stock to Ammon. In total, Miller gave Ammon $250,000.

There was only one thing left for the young man to do. The next day was a Friday, and the Syndicate usually did its best business on Fridays. Miller needed to go back to the office, work through the day, and then get back to Ammon’s office with the day’s take and all the money in the safe.

When Miller returned to Floyd Street on Friday, November 24th there was already a large crowd outside. Among them was Cecil Leslie, who had been drinking. He accosted his boss.

You damned faker! Look at those poor people! Look at that woman! I’m going to leave this place; I’m through.

Miller brushed past the inebriated Leslie and the angry crowd and the carpenters who were busy repairing the stoop, and opened for business. He caused a brief furor by refusing the first attempted withdrawal, and then loudly declaring that one week’s notice would be required for all future withdrawals, starting immediately. That made the crowd restless, so Miller calmed them down by allowing small withdrawals — provided the depositors also exchanged their deposit tickets for stock certificates, and were willing to take a check.

When Miller left his office at 1:00 PM, he quickly realized he was being followed by the police. He ditched his tail by jumping on a street car, jumping off while it was still in motion, running through a drug store and a Chinese laundry, and then catching the el and riding it to Ammon’s office. The lawyer quickly confirmed Miller’s worst fears: he was wanted man.

Miller had to go and go now. At 6:00 PM he left the city, with $200 in his pocket and a promise from his lawyer that his family would be sent along shortly, along with additional funds to hire a Canadian lawyer to plead his cause.

The next day the Kings County district attorney announced that Miller had been indicted for grand larceny and conspiracy to defraud. He had to admit the charges were a stopgap, because while everyone could agree that Miller had committed a crime no one could agree what crime it was. It sounded like fraud, but the problem with that was that even if he never intended to pay dividends his representations to the contrary were merely promissory and therefore not considered false pretenses.

In the meantime, the DA asked everyone to keep an eye out for the fugitive, who was 5’5″, 140 lbs.; with a dark mustache, small side whiskers, and a broken nose; and was wearing a mixed gray suit, overcoat, and white Alpine hat.

There was still a huge crowd outside the Franklin Syndicate office, and the mood was hopeful. Faithful depositors insisted that the charges against Miller were trumped up, leveled by plutocrats envious and resentful of the Syndicate’s success. They consoled themselves by choosing that Miller had only left town to get a jump on his weekend trading. When Ammon announced that the Boy Napoleon had pledged to “do the right thing” by his customers, a cheer went up: “Hurrah for Miller, our money’s safe!”

That opinion changed drastically on Monday, when the checks Miller had written the previous week started to bounce.

Able Was I Ere I Saw Elba

Over the next few weeks the picture of the Franklin Syndicate and the extent of its operations began to emerge. It turned out it was the biggest con anyone had ever seen.

Miller had managed to turn 12,000 investors into Grade A suckers. Daily deposits were $15,000 on average, and in the week before the collapse they had been an astounding $40,000. In October and November the syndicate had raked in $620,545 and only paid out $215,000 in dividends. It sent out so much mail it paid $40 for stamps every day, at a time when most stamps cost less than a nickel. It was impossible to say just how much money the Syndicate had made — old ledgers had been destroyed, and may have never even existed — but police accountants estimated the Syndicate had raked in more than $1,156,000 during its lifetime. That may sound like chump change to you, but it was the equivalent of about $41,500,000 in 2022 money.

As far as anyone could tell, that money was long gone. The police had only managed to recover $13,000 of it. There was $4,500 in the Syndicate’s safe when the police raided the office, along with 190 worthless shares in the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Company. There was also $8,500 that Miller’s brother Louis had grabbed so he could allow the Syndicate to make payroll. At least, that was Louis’s story. He couldn’t explain why he then thought it necessary to try and hide it in the cushions of his couch.

Miller was also long gone. There were also rumors his escape had been aided by Brooklyn policemen, as a disconcerting number of them had invested heavily in the syndicate. Everyone knew that he was in Canada, but no one could say where, and his alleged offenses weren’t the sort of thing that would get the Mounties scouring the streets of Montreal so they could extradite him.

The Syndicate was bust. A few days before November 25th, the partners had hired John Daly, the upright former sheriff of Richmond City, VA, to oversee its operations. Once Daly realized that the Syndicate intended to use him as cover for its illegal activities, or worse, as a fall guy for them, he backed out of the deal. When the Syndicate went into bankruptcy, Daly was briefly appointed the receiver and placed in charge of selling its only actual assets, the office furniture.

The cops wanted to arrest someone, and they settled on the only Syndicate partner who hadn’t fled the country: Colonel Bob Ammon. Ammon protested, claiming he was nothing more than the Syndicate’s legal counsel and had never received any money from the Syndicate other than legal fees. He had no knowledge of their day-to-day operations, and referred all inquiries about those operations to Daly. No one was buying it.

Eventually the police decided to stop pussy-footing around. They told Ammon that he had one month to produce his client, and if he couldn’t then he would be prosecuted for aiding and abetting. After they left Ammon’s office, he began frantically sending out telegrams.

On February 2nd, Miller went to the house of an acquaintance in Montreal, expecting to have a long-awaited consultation with his lawyer. Instead he was greeted by Captain James Reynolds of the Brooklyn Police Department. What followed was the most polite arrest I’ve ever heard of.

REYNOLDS: Hello, Miller. I’m captain Reynolds of Brooklyn.

MILLER: I knew it, and I’m very glad to see you. Very glad indeed. I want to get back home and that as quickly as I can. I want to see my wife and baby. I am tired of all this and I am willing to start at once.

REYNOLDS: Mind, I cannot arrest you and you are not under arrest. There is nothing to prevent you from going to Brooklyn if you want to go. I’ll do nothing to stop you, but I will now take you out of here. Understand that.

MILLER: I want to go, I tell you. I am anxious to return. Every day for the last ten days I have been on the verge of coming back for I do not want to stay here any longer. If you had not come I would have been back in a day or two.

Miller was brought back to the United States on February 4th. Once safely over the border he was arrested and charged with the only crimes the district attorney thought he could prove: grand larceny in the first degree, for absconding with the syndicate’s money; and larceny in the second degree, using a single depositor named Mrs. Moeser as a representative for each individual depositor who had been defrauded.

The Boy Napoleon spent the next two months in the Tombs. Ammon and several of Miller’s friends tried to bail him out but the district attorney refused to accept their bond, citing their connections to the Syndicate and claiming their money was dirty.

The trial began on April 2nd.

Miller’s defense team consisted of Ammon, a “Mr. House,” and former district attorney James Ridgeway. Their strategy was simple. They claimed Miller lacked mens rea, the criminal intent required for fraud, that even today he intended to repay every dime that had been deposited into his care. In fact, they said he would have been more than able to do so had the police not started to shut down his operations and limit his access to financial services.

Unfortunately for Miller, the district attorney had him dead to rights. One of the key witnesses was Cecil Leslie, who spilled everything he knew about the Syndicate’s operations after the police finally tracked him down in Utica, including the fake name on Miller’s bank account. Employees of Wells Fargo testified about the two transactions that had drained that account the day before the Syndicate’s collapse. John Daly testified about the irregularities he’d seen on his few days on the job. The defense successfully objected to district attorney’s plan to parade an army of Wall Street types and financial analysts before the jury, but the DA found a clever way around that: he immediately announced to the courtroom that he no longer required the services of the following witnesses, and then read out the full names of everyone on the call sheet. Today that would be an automatic mistrial.

The defense called no witnesses of their own, seemingly satisfied that the prosecution had failed to meet their case. In Ammon’s closing remarks, he tried to shift most of the blame to Schlesinger, who was still on the lam.

On April 16th the jury was escorted to the deliberation room, but not before the judge issued an instruction which wiped the smirk of Ammon’s face: “the fact that he did pay 10 per cent a week until he was closed up was not a circumstance to show that he intended always to pay it and must not be considered.”

After five hours of deliberation, William F. Miller was convicted on both counts. Two weeks later he was sentenced to ten years of hard time, and sent to Sing Sing.

In 1901, Miller’s conviction was reversed when an appeals court bought several of Ammon’s arguments. Ammon argued that the victims had surrendered all interest in the funds they turned over to Miller because they had received shares in the Franklin Syndicate in exchange. As stockholders they had no say over what Miller did with that money, in the same way a lender has no control over what a borrower does with their money. As a result, Miller could not be convicted of grand larceny, only of obtaining money under false pretenses. Miller was briefly released from jail, then rearrested on re-filed charges.

Fortunately those arguments held no soap with the New York Supreme Court. In January 1902 they reversed the reversal, correctly noting that were clear promises on the deposit slip, there were no shares in the Syndicate to be traded until mere days before the collapse, and there was no indication Miller had ever attempted to do any sort of speculation. They did concede that maybe the laws were a bit weird in this area.

100 Days

The Syndicate’s bankruptcy stretched out for years. Miller and Ammon were singularly unhelpful, either pleading the fifth when they were called to testify or shifting as much blame as possible on to the still-missing Schlesinger and Louis Powers, who had run the Boston office. Miller’s new (and entirely false) story was that he had been selling tea door-to-door when he ran into Schlesinger and Powers, who were the ones running the Syndicate from the shadows. Miller himself had been a mere figurehead, whose only remuneration was a $25/week salary and a wardrobe full of fashionable clothes.

The bankruptcy court was concerned with one thing: what had happened to the $405,000 that the Syndicate had taken in over its final two months and hadn’t paid out in dividends?

Some of it had been used to cover payroll and expenses. Schlesinger had taken about a third of it with him when he fled the country. That left $250,000 unaccounted for. Thanks to Leslie and others they were able to track that money to Miller’s pseudonymous bank account, right up to the moment he closed it on November 24th. A suspiciously similar amount was deposited into Ammon’s bank accounts on the following day. The problem was proving a direct link between the two events. Only one person could do that: William F. Miller.

Fortunately for them, William F. Miller was just about done with Colonel Robert Ammon.

The troubles between the two men had started early. Despite Ammon’s assurances that he would send money to Miller during his exile in Montreal that money was awful slow in coming. In fact, Miller was only able to get any money out of his lawyer by threatening to go to Canadian authorities, which persuaded Ammon to wire him a paltry amount that quickly ran out. By the time Captain Reynolds tracked him down Miller was starving and lonely, explaining why he was almost eager to be arrested.

Things were no better once Miller was back in the United States. Ammon compelled him to be silent by threatening to tank his defense and holding the $5 weekly allowance he was providing to Miller’s family over his head. Meanwhile, Ammon represented the allowance to Mrs. Miller as money coming out of his own pocket, money that she and her husband now owed him. When Miller was dragged off to Sing Sing, Ammon continued to threaten his family and bought his silence by doubling the allowance.

Once Miller’s appeals failed, Ammon abandoned him to his fate. That’s when the district attorney started working on the young man. He told Miller a different story about how he had been used. How Ammon had committed the perfect crime by stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars, with only the evidence against him the word of another criminal. How he had tried to hide that criminal where could never be found, and how when that failed, he compelled his silence by holding his family hostage.

Prison had not been kind to Miller. He was in solitary, partly because of his notoriety, but also because he had somehow contracted tuberculosis. It’s possible he was penitent and wanted to do the right thing before he died. It’s possible he was angry and wanted revenge on his ex-partner. The important part is that he came over to the DA’s side and made a big show of it with an Oscar-worthy performance full of crocodile tears.

“Mr. District Attorney,” said the wretched man in a trembling voice, with the tears still suffusing his eyes, “I am a thief; I did rob all those poor people, and I am heartily sorry for it. I would gladly die, if by doing so I could pay them back. But I haven’t a single cent of all the money that I stole, and the only thing that stands between my wife and baby and starvation is my keeping silence. If I did what you ask, the only money they have to live on would be stopped. I can’t see them starve, glad as I would be to do what I can now to make up for the wrong I have done.”

Arthur Train, True Stories of Crime from the District Attorney’s Office

Within days Miller was testifying before a grand jury, implicating Ammon in the scam. A warrant was sworn out and Ammon was arrested — ironically, during the middle of a Franklin Syndicate bankruptcy hearing at the courthouse.

The trial began in June and lasted for weeks. Contemporary accounts depict it as a battle of wills with the brusque, Svengali-esque Ammon building a towering edifice of lies, and the saintly, repentant Miller come to tear them down, even though he was tottering on death’s door. The reality was a lot simpler: it was one criminal knifing another in the back over the division of spoils. It was justice of a sort, but hardly noble.

Ammon’s defense hinged on two arguments. First, that as Miller’s former legal counsel, he was immune from prosecution. And second, that since Miller had deposited the money at Wells Fargo before transferring it Ammon, it was Wells Fargo who had received stolen property and not Ammon.

Once again, the judge’s instructions to the jury wiped the smirk off his face. First, he declared that the number of intermediaries didn’t matter when it came to receiving stolen money, only the end result, which was some $250,000 in Ammon’s account. Then, just for good measure, he added:

Something has been said by counsel to the effect that the defendant, as a lawyer, had a perfect right to advise Miller, but I know of no rule or law that will permit counsel to advise how a crime can be committed.

The jury wasn’t out for long. On June 17, 1903 Robert Ammon was convicted of receiving stolen goods and sentenced to four years hard labor. It was the maximum sentence allowable under New York State law, which said that the receiver of stolen goods could not serve more than half the time served by the original thief.

Exile on Main Street

Only a small amount of the missing money was ever recovered and returned. Most Franklin Syndicate depositors were financially ruined. Or rather, given that Miller had preyed on the most economically insecure part of the population, more financially ruined than usual.

Robert Ammon served his entire sentence and was released in 1907. Astoundingly he was not disbarred for his malfeasance, and continued to use his knowledge of the law to shield white-collar crooks from the consequences of their actions. He died on April 19th, 1915 in Green Cove Springs, FL. In his will he screwed over his estranged wife and kids by leaving all his money to his long-time side piece.

Sightings of Edward Schlesinger kept dribbling in for years, usually from tourists who spotted him in the casinos of Europe. Somehow he managed to beat the house in Monte Carlo, Paris, Baden Baden, and Alexandria. There’s one house that always wins, though, and eventually God called in his marker, though no one can agree whether that was in 1904 or 1910.

District Attorney William Travers Jerome began advocating for Governor Benjamin Odell to commute William F. Miller’s sentence, as a quid pro quo for his testimony in the Ammon trial. Odell refused, but in 1905 newly elected Governor Frank Higgins agreed. It was a humanitarian gesture, as no one expected the consumptive Miller to live more than a few years.

After his release from prison, all traces of William F. Miller’s tuberculosis miraculously disappeared.

He was briefly a partner in a restaurant on Montague Street, but it failed. Eventually he moved out to Rockville Center on Long Island and was forced to take a job working in a grocery, the sort of blue-collar work he’d always thought was beneath him. To avoid unnecessary publicity (and also civil suits from former Franklin Syndicate marks) he used his wife’s surname, Williams-Schmidt, but even that alias was exposed after he had a brawl with his father-in-law in public.

He continued to deny any role in the scam, and to place the lion’s share of the blame onto Ammon and Schlesinger. Eventually he dropped out of the news entirely. Presumably he died, though no one can say exactly when.

The legacy of the Franklin Syndicate managed to outlive all of its principals. In the 1920s there was a young immigrant who had read of Miller’s exploits back when he was a pimply-faced teenager in Italy, and admired the brazen boldness of the Boy Napoleon of Finance. He took the age-old scam Miller had refined, and perfected it to the point where the entire scam is now forever associated with his name.

That name? Carlo Ponzi.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

The Christian Endeavour Society that Miller used to kick-start the Franklin Syndicate would later go on to picket fraudulent medium May S. Pepper (“A Good Thing to Die By”).

Robert Ammon isn’t the first individual we’ve encountered with a significant connection to the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The strike was also where John Ignatius Rogers first made his name — although Rogers was on the other side, beating down strikers as a colonel in the Pennsylvania Army National Guard. Colonel Rogers went on to become the notoriously cheap and litigious owner of the Philadelphia Phillies (“French Leave,” “Triple Jumper,” “The Buzzer Brigade.”)

Sources

- Bruce, Robert V. 1877: Year of Violence. Chicago: Bobbs-Merrill, 1959.

- Gless, Alan G. “Self-Incrimination Privilege Development in the Nineteenth-Century Federal Courts.” American Journal of Legal History, Volume 45, Number 4 (October 2001).

- Gribben, Mark. “The Franklin Syndicate.” Malefactor’s Register. https://malefactorsregister.com/wp/the-franklin-syndicate/ Accessed 6/22/2021.

- Oltmann, V.G. The Ponzi Files: William “520%” Miller. Vancouver: The Fraud Chronicles, 2014.

- Pearce, Arthur R. “Theft by False Promises.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Volume 101, Number 7 (May 1953).

- Ryan, John A. “The Ethics of Speculation.” International Journal of Ethics, Volume 12, Number 3 (April 1902).

- Train, Arthur. “The Story of the Franklin Syndicate.” American Illustrated Magazine, 1 Dec 1905.

- Train, Arthur. True Stories of Crime form the District Attorney’s Office. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912.

- “Bucket shop (stock market).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bucket_shop_(stock_market) Accessed 6/22/2021.

- “Rocktroh, like another Col. Sellers, saw millions in his exposition club.” New York World, 2 Sep 1899.

- “Banks turn Miller from their doors.”” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 22 Nov 1899.

- “Franklin Syndicate not incorporated.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 23 Nov 1899.

- “Miller indicted.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 24 Nov 1899.

- “Miller not found.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 25 Nov 1899.

- “Police not able to find any trace of Miller.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 26 Nov 1899.

- “How Miller eluded his would-be captors.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 27 Nov 1899.

- “Miller’s safe opened and no money found.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 28 Nov 1899.

- “Hearing in Miller Case set for next Tuesday.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 29 Nov 1899.

- “Reynolds on still hunt for William F. Miller.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 3 Dec 1899.

- “Syndicate Miller is still at liberty.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 5 Dec 1899.

- “Franklin Syndicate’s mail.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 6 Dec 1899.

- “William F. Miller not in New York.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 7 Dec 1899.

- “Miller Hunt goes on, police more hopeful.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 9 Dec 1899.

- “Hopes to catch Miller.” Boston Globe, 4 Jan 1900.

- “Packer sentenced.” Buffalo (NY) Times, 14 Jan 1900.

- “Franklin Syndicate assets $32,528.” New York Tribune, 17 Jan 1900.

- “Miller jailed in Brooklyn.” Brooklyn Standard-Union, 9 Feb 1900.

- “William F. Miller caught by Reynolds.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 8 Feb 1900.

- “Miller to be tried early next April.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 9 Feb 1900.

- “Syndicate Miller is still in jail.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10 Feb 1900.

- “Cecil Leslie, Miller’s press agent, will surrender to authorities.” Brooklyn Evening Standard, 13 Feb 1900.

- “The story of Cecil Leslie.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 14 Feb 1900.

- “Bunco game.” Boston Globe, 14 Feb 1900.

- “Miller said to have at least 17,000 creditors.” Brooklyn Standard Union, 16 Feb 1900.

- “Seventeen indictments against W.F. Miller.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 23 Feb 1900.

- “Miller may be forced to remain in jail.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 24 Feb 1900.

- “Six indictments found, five arrests soon follow.” Brooklyn Standard Union, 7 Mar 1900.

- “Dean Company swindle.” New York Times, 15 Mar 1900.

- “Brooklyn victims of William F. Miller’s Franklin Syndicate.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 18 Mar 1900.

- “Miller’s partners in Egypt.” New York Tribune, 25 Mar 1900.

- “Clarke opens his case against W.F. Miller.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 4 Apr 1900.

- “Mrs. Moeser testifies at the Miller trial.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 5 Apr 1900.

- “Hint from Ridgeway as to Miller’s defense.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 6 Apr 1900.

- “Miller’s creditors fail.” New York Times, 8 Apr 1900.

- “Miller bought U.S. bonds while running syndicate.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 9 Apr 1900.

- “Eight witnesses testify at the trial of Miller. Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10 Apr 1900.

- “Miller case expected to get to the jury to-day.” New York Tribune, 11 Apr 1900.

- “Stamp robbery arrest.” New York Tribune, 13 Apr 1900.

- “Miller is guilty, said the jury.” Brooklyn Citizen, 17 Apr 1900.

- “Syndicate Miller must go to Sing Sing.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 Apr 1900.

- “W.F. Miller declares his backers are guilty.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 2 Jun 1900.

- “Miller still refuses to answer the lawyers.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 6 Jun 1900.

- “Miller’s lawyer, Ammon, put in the witness chair.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 28 Sep 1900.

- “Col. Ammon’s reticence.” Brooklyn Standard Union, 29 Sep 1900.

- “Robert A. Ammon arrested.” Boston Evening Transcript, 3 Apr 1901.

- “Two ferryboats crash together; scores drowned.” Buffalo (NY) Courier, 15 Jun 1901.

- “Three thousand one hundred and ten victims of the William F. Miller syndicate will receive only six per cent of their original investment.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle,

- 17 Jul 1901.

- “A new trial granted to syndicate Miller.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 11 Oct 1901.

- “Says Miller conviction will be sustained.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 Oct 1901.

- “Syndicate Miller back in Raymond Street jail.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 Oct 1901.

- “Miller gets retrial.” Boston Globe, 18 Oct 1901.

- “Miller victims to get 75 per cent.” New York Evening World, 19 Oct 1901.

- “More of Miller’s 520 per cent scheme.” Boston Post, 22 Oct 1901.

- “Summons for Lord to appear in court.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 22 Oct 1901.

- “Neufield said to know who has Miller money.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 30 Oct 1901.

- “Miller says he gave to Ammon $180,000.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 31 Oct 1901.

- “Col. Ammon arrested at referee’s hearing.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 7 Nov 1901.

- “Ammon arrested after testimony.” Boston Post, 8 Nov 1901.

- “Ammon calls Goslin ‘a pig’ on the stand.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 19 Nov 1901.

- “Bail for W.F. Miller fixed at $72,500.” Brooklyn Times Union, 13 Dec 1901.

- “Miller had bail ready and was going to skip.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 15 Jan 1902.

- “Court of appeals opinion in William F. Miller case.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 19 Jan 1902.

- “Found in Monte Carlo.” Brooklyn Times Union, 31 Mar 1902.

- “520 per cent Miller is in Brooklyn to-day.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 21 Apr 1902.

- “Syndicate Miller loses.” Brooklyn Times Union, 9 Sep 1902.

- “To extradite Schlessinger.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 11 Oct 1902.

- “Syndicate, says Miller, ran by Ammon’s advice.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10 Jun 1902.

- “520% Miller confesses all.” New York Evening World, 22 May 1903.

- “A steal, pure and simple, says 520 per cent Miller.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 11 Jun 1903.

- “Ammon got the bonds from Miller’s father.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 Jun 1903.

- “‘Bob’ Ammon convicted; he may get five years.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 18 Jun 1903.

- “Col. Ammon convicted.” Brooklyn Citizen, 18 Jun 1903.

- “Miller tells in detail where the money went.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 8 Jul 1903.

- “Ammon faces Miller, but both men are wary.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 15 Dec 1903.

- “520 per cent Miller to be free on Monday.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 10 Feb 1905.

- “Missing ‘Miller’ money may be recovered at last.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 16 Apr 1905.

- “Syndicate Miller fails ase restaurateur.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 24 Oct 1906.

- “Colonel Bob Ammon is in trouble again.” Fergus County (MT) Democrat, 6 Dec 1910.

- “A millionaire’s colony.” New York Tribune, 8 Dec 1910.

- “Love of 79 for 43 worth but $6,000 in to-day’s market.” New York Evening World, 4 Oct 1911.

- “Arrest ‘Bob’ Ammon twice.” New York Tribune, 11 May 1912.

- Bain, George Grantham. “Vaccuum washer company now in limelight.” Idaho Statesman, 28 Jul 1913.

- Rigby, Cora. “The lure of easy money.” Hartford Daily Courant, 9 May 1915.

- “Col. R.A. Ammon dies.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 May 1915.

- “520% Miller in more trouble.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 5 Oct 1915.

- “Lost wife’s love, sues 520 P.C. Miller.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 Jan 1916.

- Harris, Henry W. Jr. “Gigantic Swindles V: 520-Percent Miller.” Boston Globe, 21 Oct 1921.

- “520 per cent. Miller got $1,700,000 on $50 in simple tenement.” New York Herald, 18 Mar 1922.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: