What Joy to the Troubled Heart!

the tale of William H. Mumler, spirit photographer

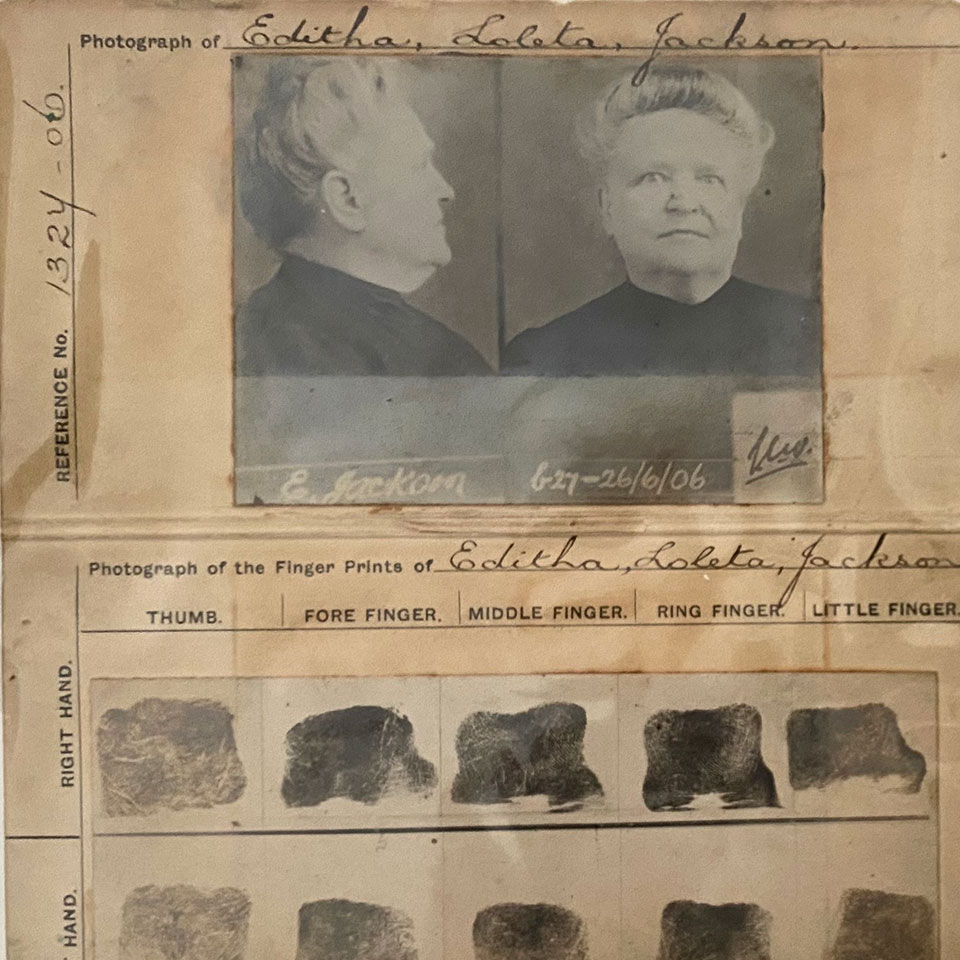

William Howard Mumler was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts in 1832.

His childhood seems to have been happy and unremarkable, and eventually he grew into a stout young man with surprisingly delicate hands, a big bushy beard, and a mop top of unruly hair. In his early twenties he heard the call of the big city and moved south to Boston.

Young Mr. Mumler was a man of many talents: an artist, a printer, a mechanic, a chemist, an inventor. He knew something about everything. (My kind of guy.) He put those skills to use as an engraver for Bigelow Brothers and Kennard, transferring elaborate decorative patterns onto jewelry, watches, and flatware. His work was consistently excellent, and he was paid well for it: about $8/day, a solid middle class salary in those days.

He also had a side hustle peddling patent medicine. “Mr. Mumler’s German Remedy” was touted as a cure for dyspepsia, which is surprising because it was mostly alcohol, which aggravates dyspepsia. Sales were strong, and in 1861 Mumler was able to quit his job and open his own printing and engraving shop.

Now that he was his own boss, Mumler had more free time than he knew what to do with. So he did what a lot of people do: he want back to school. Every Sunday he went down to Stuart’s Photographic Gallery, 258 Washington Street, where he studied the wet plate photographic process… and also made goo-goo eyes at his teacher, Mrs. Hannah Green Stuart, a comely and charismatic young widow.

In early 1862, Mumler was goofing around in the studio and decided to take a self portrait. He set up a fancy chair and parlor table in front of a curtain, framed the tableau in the camera’s viewfinder, then struck a pose resting his hand on the back of the chair. As he snapped the shutter he thought he felt a “tremulous motion on his right arm” but ignored it. He felt exhausted, but took his plate back into the back and started developing it.

Mumler had been alone in the studio, but the finished print showed a young dark-haired woman sitting in the chair next to him. She was out of focus and washed out, like she had been moving rapidly. Despite that her head and shoulder seemed to be solid, blocking the view of the drapery behind her. Her lower body was transparent, and you could see the chair through her.

Playwright Dion Boucicault had coined the phrase, “The camera never lies,” in 1859, but Mumler knew that wasn’t true. There were many ways you could make the camera lie: compositional tricks like forced perspective; in-camera tricks like double exposure; processing tricks like double printing that could be deployed during the development process.

Mumler figured that he had accidentally achieved one of these effects. Negative plates were very expensive back then, so they were usually cleaned and re-used. He probably hadn’t wiped it off completely, leaving some of the previous image behind, invisible to the naked eye until a print was lifted from it. It looked neat, though. He showed his photo to Hannah, expecting she would have a good laugh. Instead she told him he had taken a picture of a ghost.

I’m sure you’re familiar with Arthur C. Clarke’s declaration: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” In the 1860s, that sufficiently advanced technology was photography and people thought it could do almost anything.

The cliché example would be some “primitive tribesman” who thinks the camera has stolen his soul, but that “primitive tribesman” would hardly be alone. Balzac, the titan of French literature, believed that our physical bodies were made of layered images and that photographs stripped those layers away and made you less of a person. Many otherwise reasonable people believed the camera was capturing more than mere images, that it was capturing absolute truth, the very essence of the things it was pointed at, including that which could not be seen by the human eye. They weren’t entirely wrong. Cameras can be used to record all sort of things that would otherwise be invisible, like infrared light and electricity and x-rays.

Then again, they also thought cameras could take pictures of ghosts.

Now, early photographers were sometimes called “necromancers” because they took a lot of photos of dead people. (Because they were the only subjects who could sit still for a long exposure.) This was more than that. In the mid-Nineteenth Century everyone went nuts for Spiritualism, a new religion which claimed there was a world of ghosts and spirits which existing alongside our own. The only thing separating the living from the dead was our inability to perceive it. Well, unless you were a Spiritualist medium, with the ability to breach the barrier between worlds and communicate with the other side.

Starting in the 1850s photographers had made numerous attempts to capture spirits on film, but none had been successful. Well, until now.

Hannah Stuart was a devout Spiritualist. If she insisted that the woman in the picture was a spirit, well, William Mumler wasn’t going to argue with her. They took the print and hung it up on the wall as a novelty.

And that’s where it stayed, until the day Dr. H.F. Gardner walked through the front door.

Gardner was a mover and shaker in Spiritualist circles, an early convert who had arranged the Fox Sisters’ first tour of Boston. He saw Mumler’s novelty photograph and immediately declared that it was a genuine photograph of a spirit. He purchased the print and had Mumler write down how some details about how it was created. The photographer added some dramatic flourishes like the bit about his trembling arm and being exhausted, and the new information that the seated figure was a deceased cousin. That convinced Gardner that Mumler was a new and exciting form of medium, a “spirit photographer.”

Of course, his mediumship would have to be tested.

What you need to understand is that Spiritualists did not think of their movement as a religion but a new science, and were bound and determined to follow the scientific method. That’s why the Spiritualist vocabulary includes phrases like “test medium” and “control spirit.”

In reality, they were only pseudo-scientists, interested in adopting the form of science without taking on any of its philosophy or content. Their hypotheses were all based on an axiom that they were not willing to revisit — that the supernatural was real. Their standard of proof was laughably trivial, and their results were worthless.

Mumler’s first test was simple: Gardner sat for a spirit photograph of his own, and the finished image showed a ghostly figure by his side. Now, in most of Mumler’s photographs the so-called spirits are so faint and indistinct, and no detail can be discerned. That let viewers project their preconceptions on to the figure, the visual equivalent of the Forer effect. In Gardner’s case, he identified the pale blob as his late son. That, at least, merited another round of tests.

For the next round, Gardner brought in an expert. Photographer James Wallace Black was asked to recreate Mumler’s spirit photographs, but just couldn’t figure out how they were done. In frustration he sent an assistant down to Stuart’s to observe Mumler in action. The assistant returned to report that everything seemed to be above board, and then showed off a portrait Mumler had taken of him with the “ghost” of his late father.

Black realized that his assistants were useless, and he would just have to see things for himself. He offered Mumler fifty dollars for a genuine spirit photograph produced without trickery. He had free rein of the studio and watched Mumler like a hawk. He didn’t spot any funny business, yet there it was, a translucent figure resting its arm on his shoulder. Black knew when he was beat, and got out his wallet to make good on his bet. Mumler refused to take the money, and sent Black on his way with the print as a free souvenir.

It’s easy now to see that Black’s test was badly designed. Mumler was allowed to use his own camera and tools in an uncontrolled environment. Black did not inspect the camera, or the plate, or the paper because he thought Mumler was too dumb to tinker with them. Mumler took advantage of that arrogance to channel Black’s investigation towards the areas of the process where trickery was not involved. By letting Black off the hook at the end he made himself look like a good guy, while still showing that he was the one with the power in the relationship. In short Black’s test proved nothing, unless you already believed in spirits.

Fortunately for William H. Mumler, Dr. H.F. Gardner already believed in spirits.

Gardner wrote about Mumler and spirit photography in a series of essays that were published in prominent Spiritualist newspapers like New York’s Herald of Progress and Boston’s Banner of Light. Thanks to the free publicity Mumler became the most sought-after photographer in Boston. Anyone who was anyone just had to have their photo taken with a real ghost.

Mumler warned his clients that he couldn’t guarantee a ghost in every photo, and they still kept coming. To meet demand he started working in the studio for two hours every afternoon; eventually he had to close the engraving shop and become a full-time photographer.

When it became obvious that the demand wasn’t going away, Mumler jacked up the price, charging $10 for a dozen cartes de visite (wallet-sized photos, basically). That may not sound like a lot, but at the time regular cartes de visite sold for about a quarter apiece. The higher price point did nothing to reduce demand, but it did allow Mumler to pivot to a higher class of customer.

His new customers Boston’s richest and most socially distinguished citizens:

- crusading journalist William Lloyd Garrison;

- noted Spiritualist medium Fannie Conant;

- shipping magnate Alvin Adams of Adams Express, the largest delivery firm in the country;

- and widow Eliza Babbitt, whose late husband Isaac invented a flexible alloy called “Babbitt metal” that is still used in bearings to this day.

He even had repeat customers. Infamous Copperhead William “Colorado” Jewett had been hitting up Spiritualists to get advice from the country’s greatest (and latest) statesmen when he dropped by the studio to have his picture taken with the ghost of John Adams. Then a few days later he came back to have his picture taken with Daniel Webster. And then Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and Stephen Douglas. (Mumler eventually drew the line at conjuring up the ghost of George Washington, which felt somewhat sacrilegious.)

You may find yourself wondering how intelligent, well-to-do folks fell for such an obvious scam. Well, all the money and education in the world doesn’t make you immune to being scammed. There’s also the distinct possibility that some of them weren’t fooled at all. The late Nineteenth Century was a sentimental age, and it’s possible they just wanted a memento mori or a final photo with a deceased loved one. There’s every chance they knew they were being scammed, and played along because it was a price they were willing to pay.

Regardless of what his sitters may have thought, Mumler presented himself as a legitimate medium, though he could offer no explanation for how he came by this talent. He was just happy to just snap away and let others come up with explanations for his “extraordinarily abilities” later. If he was pressed, he would just say that electricity was somehow responsible, because in a way electricity is responsible for everything, right? It’s basically magic.

Some people were still not impressed.

Skeptics were bound and determined to prove that you couldn’t take photo of a ghost. Attacking the existence of ghosts was usually more trouble than it was worth, so instead they drew attention to the numerous methods you could use to recreate “spirit photographs” that looked a lot like Mumler’s. The problem was that the recreations weren’t exact. Somehow the spirits in Mumler’s photos could be obscured by solid objects as if they existed in three dimensional space, an effect that you couldn’t achieve with a regular double exposure. Eventually photographer L.H. Hale discovered how to perfectly recreate Mumler’s photos by using of multiple negative plates and overprinting, but his discovery came too late. Mumler had already been tested by an army of less savvy technicians, and their endorsements were the only one he needed. He announced he had nothing else to prove and refused to submit to further tests.

That didn’t sit well with established Spiritualists. Many of them began to turn against Mumler. Fannie Conant was careful to neither endorse or debunk spirit photography:

There is much that is genuine true, beyond the possibility of doubt, surrounding this recent unfoldment of spirit-power. There is also much that is untrue, and which has its origin not in the world spiritual, but in the world material… In as much as you have the faculty to divide the right from the wrong, the false from the genuine, it is your duty to exercise it, and to weight the balances of your own judgment all that is presented you from the spirit-world, or from the world in which you now live.

(And just in case that wasn’t equivocal enough for you, Conant made it very clear that those weren’t her words but the words of her control speaking through her.)

Andrew Jackson Davis was far less equivocal. He actively tried to take down Mumler by sending his own photographer, William Guay, up to Boston to investigate the spirit photographer. Guay didn’t find any fraud, and then quit his job to study Mumler’s technique. That was a short-term victory for Mumler that wound up backfiring spectacularly.

Guay, you see, had a background in the amusements industry. Under his guidance Mumler’s presentation became more theatrical and carnivalesque: spirit rapping accompanied the photographer’s entrance, mystic hand gestures were incorporated into the picture-taking process, the camera would rattle and levitate like a tipped table. The show was a crowd pleaser for the rubes… but it outraged serious Spiritualists and seemed tawdry to the well-to-do. Even carnies like P.T. Barnum, who had been displaying Mumler’s photos in his American Museum, were disgusted by the cheap theatricality of it all.

Over time Mumler’s novelty began to fade, and it became clear that he had tapped out the local audience. He pivoted and opened a mail order spirit photography business. All Mumler needed from Mrs. Jane Q. Public was a money order for $7.50, a self-addressed stamped envelope, and a detailed physical description of her dead husband. Just so he would know he’d conjured up the correct late Mr. John Q. Public, of course.

Earlier, the scuttlebutt in Boston had been that Mumler had accomplices who would break into homes, surreptitiously remove photos of the deceased so Mumler could copy them, and return the originals before they were missed. That had always seemed unlikely — what if the deceased had never been photographed? — but there was absolutely no way you could scale up that operation to support a mail order business. Mumler would have had to have dozens of far-flung accomplices across the nation.

But if he was getting detailed physical descriptions of the deceased, he just had to search through some sort of photo library to find a close match. Then he could bleach out the fine details and let the power of suggestion take care of the rest. That would explain some of the other irregularities people had been noticing, like that some spirits seemed to appear over and over again in different contexts.

The most memorable of these spirits was a woman with a distinctive ornate hat who appeared in numerous photos as a mother, grandmother, or cousin. Eventually an editor at the Banner of Light realized it was a friend of his who was very much not dead. Years earlier she had her portrait taken by Hannah Stuart wearing a prop hat that had been around the studio, and hated the results so much that she refused to accept delivery. The plates and proofs were still at the studio.

There was also the woman who had a photo taken with her brother, who had died while fighting in the Civil War… except he too, was very much alive. Mumler’s defense was that the brother had been impersonated by an evil spirit… Though no one seemed to follow that through to the ultimate conclusion, that all of the spirits in the photos were evil impostors.

By February 1863 these incidents were too numerous to ignore, and the Banner of Light launched an anti-Mumler campaign. It was wildly successful: Mumler’s reputation was dragged through the mud, and even Dr. Gardiner turned against him. Mumler withdrew from the spotlight and quietly stopped taking spirit photographs.

The studio survived, partly thanks to the innate charisma and brilliant salesmanship of Hannah Stuart, who by this point was Mrs. William H. Mumler. But things were never quite the same again.

What Balm to the Aching Breast!

Then William Guay came back into the story. After studying under Mumler, Guay left to start his own “Photographic Temple of Art” in New Orleans. It didn’t do so well, and in early 1868 he had to declare bankruptcy. Despite that failure he still believed that spirit photography had unrealized potential, and returned to Boston to let Mumler know that there was a vast untapped market for his services. The two men formed a partnership and decided to take the show on the road.

In November 1868 they moved to New York and sublet a photography studio on Broadway from one W.W. Silver. Their timing was perfect — the Civil War had just finished making thousands of new ghosts and millions of grief-stricken survivors. It wasn’t long before customers began trickling in.

Initially the partners tried to keep Mumler’s involvement on the down low. Advertisements mentioned spirit photography without mentioning the spirit photographer by name. Even Guay tried to keep his identity a secret; he would introduce himself to customers as the manager of the studio, and didn’t correct them when they assumed he was W.W. Silver.

Eventually, though, they sought the endorsement of New York Spiritualist Conference, which meant they had to divulge their true identities. The Conference told Mumler that they would need to subject him to another round of tests, which he agreed to… but only if they paid him for his time and materials. Well, that was just not done, and the Conference issued a resolution calling Mumler a fraud without actually calling him a fraud:

Resolved: That this conference considers that Mr. Mumler does not meet this attempted investigation in such a manner as we should expect from one conscious of having a great truth in his possession, and that while thus refusing to the Committee of this Conference the privilege on fair terms of such an investigation as must necessarily help to confirm his claims if true, he had no right to expect from us as a body the endorsement which some individuals see reason to give him, or any conference whatever.

Mumler and Guay decided to forge ahead without the Spiritualists’s blessing. They printed up promotional pamphlets explaining the nature of their services, which Mumler signed with his own name.

My object in placing this little pamphlet before the public, is to give to those who have not heard, a few of the incidents and investigations on the advent of this new and beautiful phase of spiritual manifestations. It is now some eight years since I commenced to take these remarkable pictures; and thousands, embracing as they do scientific men, photographers, judges, lawyers, doctors, ministers, and in fact all grades of society, can bear testimony to the truthful likeness of their spirit friends they have received through my mediumistic power. What joy to the troubled heart! What balm to the aching breast! What peace and comfort to the weary soul! to know that our friends who have passed away can return and give us unmistakable evidence of a life hereafter — that they are with us, and seize with avidity every opportunity to make themselves known; but alas! in many instances, that old door of sectarianism has closed against them, and prevents their entering once more the portals of their loved ones…

The pamphlet worked. The initial trickle of customers turned into a steady stream, and then a raging torrent. By March 1869 Mumler and Guay were able to buy out W.W. Silver and completely take over the studio. Things were looking up.

Until quite suddenly they weren’t.

In March 1869 Mumler submitted several of his spirit photographs to the Photographic Section of the American Institute, which put the on display as art. That drew the ire of Institute member Patrick V. Hickey, the science correspondent for the New York World. As a photographer Hickey saw Mumler as an entertainer making a mockery of his art form; as a scientific skeptic he saw Mumler as a dangerous charlatan who needed to be exposed; as a Catholic he saw Mumler as a spiritual cancer that needed to be excised.

Hickey set out to study Mumler’s methods by visiting the studio and observing his target in action. He was not impressed by what he saw. He witnessed high-pressure sales tactics, which included over-eager salesmen and interactions with other salesmen pretending to be repeat customers. He listened as assistants pressed sitters for detailed physical descriptions of their loved ones. He noted the over-the-top theatrics which were still a part of Mumler’s whole act. He watched as Mumler and his female assistant (presumably Hannah) were extremely particular about how they positioned their suspects.

The entire vibe of studio was off. Weird vibes aren’t exactly actionable, though, so Hickey hit the library to see what he could dig up about Mumler. It wasn’t long before he unearthed the story of the photographer’s meteoric rise and fall in Boston. That wasn’t exactly proof either, but it was something.

Hickey marched into City Hall to shout at Mayor Abraham Oakey and demand that the city do something about William H. Mumler. Oakey was only too happy to oblige. He wasn’t exactly motivated by truth and justice, though; he was just trying to stick it to his political opponents, most of whom were Spiritualists. Oakey assigned the case to Marshal T.J. Hooker… er, excuse me, J.H. Tooker.

On March 16, Tooker dropped by Mumler’s studio, introduced himself as “William Wallace” and asked if he could have a photo taken with the spirit of his late father-in-law. A few days later he returned to pick up his cartes de visite, and sure enough, there was shadowy figure standing next to him in the prints. The marshal didn’t recognize the man, but Mumler was very insistent that it had to be his father-in-law.

It wasn’t. Tooker paid for the prints, then immediately arrested Mumler for fraud.

Mumler was thrown into the Tombs for a few weeks as his case worked its way through the system. He was formally arraigned on April 12 and was uncharacteristically combative.

JUDGE: “What is it you’ve got to say to this charge?”

MUMLER: “I have nothing to say.”

JUDGE: “Do you pretend that you take spirit photographs by supernatural means?”

MUMLER: “I have no answer to make to this question either. I demand an examination.”

A plea of not guilty was entered on his behalf, and Mumler was returned to his cell. Then Hannah and Guay went out and got the best lawyer they could afford, “The Fighting Lawyer” John D. Townsend. That was a bit shocking — Townsend was one of the best criminal defense attorneys in the city, known for defending the accused in high profile murder trials. Something as simple as fraud almost seemed beneath him.

It may be that he relished a chance to butt heads with prosecutor Elbridge Gerry. Not James Madison’s Vice President, the one who gave us the word “gerrymander”, he’d been dead since 1814. This was his grandson, one of the glory hogs who helped create the stereotype of the crusading district attorney. Gerry had chosen Mumler’s trial to be his next crusade, and it quickly grew from a simple fraud prosecution into a sweeping assault on Spiritualism itself.

The trial began on April 21, 1869, though it’s worth stressing this wasn’t actually a trial. It was actually just a preliminary hearing on habeas grounds, reviewing the evidence to see whether there was enough of it to send the case before a grand jury. (Yes, that’s right, Mumler had spent a month in the Tombs even though he hadn’t been officially indicted yet. He would spend another two weeks in the Tombs while the “preliminary hearing” spun out of control.)

The prosecution’s case was simple, if grand in scope. Mumler claimed to medium capable of taking photographs of spirits, but spirits did not exist. Therefore, the photos must have been produced through some form of trickery. Selling these tricks as “genuine” spirit photographs therefore constituted fraud and theft.

Patrick V. Hickey was the first witness called. For several weeks he had been using his column in the World to denounce spirit photography in general and Mumler in specific. He testified about his visit to Mumler’s studio, his research into the photographer’s checkered past, and his subsequent attempts to replicate Mumler’s technique.

J.H. Tooker was up next, and he recounted the story of his experiences at Mumler’s studio, as well as the subsequent arrest. He was particularly hostile, calling the studio a place where “the tenderest sympathies of human nature were daily outraged.” Unfortunately, he collapsed on cross-examination when he was forced to confess that he had never actually seen his late father-in-law while he was alive, and could not assert with total confidence that the figure in his spirit photograph wasn’t him.

Then it was William Guay’s turn. He spoke of his long association with Mumler, their current business arrangements, and volunteered several ways spirit photographs could be faked while insisting that Mumler did not use any of these techniques. For the most part, though, he claimed that he could not remember anything of interest, which was likely a dodge so that he didn’t have to plead the Fifth. After all, he was Mumler’s partner and likely to be dragged into any fraud prosecution. It wouldn’t do to draw attention to the fact that he had been masquerading as “W.W. Silver” to prospective customers.

The rest of these witnesses I’m going to do out of order, because it makes for a tidier tale.

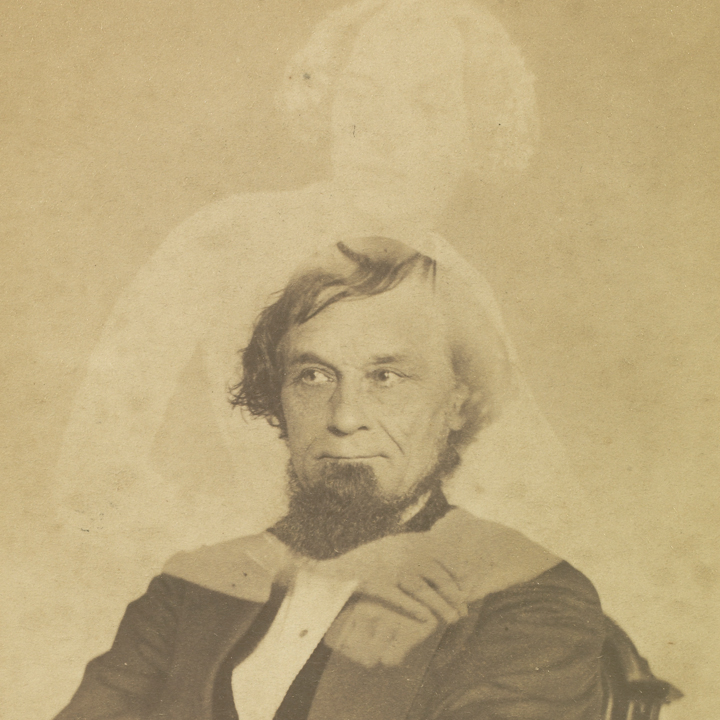

Photographer Abraham Bogardus testified about his experience making fake spirit photographs, including a relatively famous one of P.T. Barnum with the “ghost” of Abraham Lincoln floating overhead. This was when the defense started to get spicy. When Bogardus denied the existence of spirits Townsend tried to discredit him by reading from the Bible, specifically, the story of the Witch of Endor conjuring the spirit of the prophet Samuel (1 Samuel 28). The judge was having none of that, and ruled that the Bible was inadmissible and irrelevant to the case.

The prosecution called other photographic experts, including Oscar Mason and Charles Hull of the American Photographic Society, who rattled off a list of methods could be used to fake spirit photographs. The list included our old favorites, including partially cleaned plates, double exposures, superimposures, and overprinting; but also included some head scratchers “inserting a little figurine in the camera” and “having an accomplice dressed as a ghost jump out when the photo was taken and then hide before anyone noticed he was there.”

In response Townsend and Mumler pointed out that they were not arguing images could not be faked, merely that Mumler himself was not faking them. To that end, they brought out their own legion of photographic experts: William P. Slee, Samuel Fanshaw, Jeremiah Gurney, William W. Silver, and more. Each of them had investigated Mumler at one point or another, and none of them had been able to detect any sort of fraud. They could not assert with 100% confidence that no trickery was involved in the production of the photos, but they could assert that if it was involved it didn’t involve any of the methods described by the prosecution. Slee’s testimony was of particular note, since he testified that Mumler was able to create his spirit photographs with using other people’s equipment and tools.

Then there were the character witnesses, about a dozen of them, most of them Spiritualists, all customers of Mumler’s who proudly showed off spirit photographs with their dead wives and sons and cousins and neighbors. If they were satisfied with Mumler’s services, what grounds did the Gerry have to prosecute him for fraud?

Perhaps the most eloquent of these witnesses was John W. Edmonds, a former New York Supreme Court judge and devout Spiritualist. He could not say whether the figures in Mumler’s photographs were actually spirits, but argued that some discretion was called for:

Spiritualists reason that these photographs are actual pictures of disembodied spirits, but they do not know. I am not prepared myself to express a definite opinion. I believe, however, that in time the truth or falsity of spiritual photography will be demonstrated and I therefore say it would be best to wait and see. The art is yet in its infancy.

Then Gerry pressed Edmonds with detailed questions about what spirits wore and did in the next world. Edmonds’ confident, matter-of-fact responses made him sound like an utter loon.

As for the prosecution, their most eloquent witness was some guy named Phineas Taylor Barnum. That’s right, the Greatest Showman himself. Barnum claimed to be belief in “spooks” but he was no Spiritualist — in fact, he had nothing but contempt for those who preyed on the emotions of bereaving families. Yes, he had displayed Mumler’s at the American Museum as a humbug, but he had pulled them down when he realized they weren’t the right sort of humbuggery.

I have never taken money for things I misrepresented. I may have draped one or two of my curiosities slightly… I never showed anything that did not give the people their money’s worth four times over. These pictures I exhibited, I did so as a humbug, and not as a reality — not like this man who takes ten dollars from people…

If people declare that they privately communicate with or are influenced to write or speak by invisible spirits, I cannot prove that they are deceived or are attempting to deceive me. But when they pretend to give me communications from departed spirits, I pronounce all such pretensions ridiculous.

Eloquent indeed, even if the version of Barnum’s history and ethics presented was, shall we say, highly edited.

The proceedings finally wrapped up on May 5 after two weeks of highly contentious testimony. Gerry was in high dudgeon, attacking the very concept of Spiritualism and supernatural and demanding that an example be made of Mumler.

Townsend was also in fine form. He thundered that spirits were real, Mumler took photographs of them through some mechanism he could not explain, and despite Gerry’s pretty words and numerous witnesses the prosecution could not actually prove otherwise. He even alleged that the prosecution was motivated purely by religious bigotry, and noted that by Gerry’s definition it wasn’t just the 33% of Americans who believed in Spiritualism who were crazy — it was everyone who believed in Christianity. To drive the point home, and partly in protest of the judge’s earlier ruling, he rattled off an exhaustive list of every time angels and spirits were mentioned in the Bible.

Judge Joseph Dowling deliberated for less than a minute before issuing his decision.

The case in question was one of fraud. Gerry’s primary argument was that spirits did not exist, and therefore any photographs of spirits were therefore fraudulent. But the district attorney was wrong about how law treats the supernatural. Since the existence of the supernatural was something that could not be proved or disproved through the law, it had to be agnostic on such matters. Assertions that spirits did not exist could not be used to prove fraud. That meant the real issue at hand was not whether spirits were real, but whether Mumler was using fraudulent means to fake photographs of spirits.

Prosecution witnesses had suggested several methods which could be used to generate spirit photographs, but could not specify which of them Mumler had been using. Defense witnesses argued that Mumler had been investigated several times, and had not been found to use any of them. Those defense witnesses may have been fooled (and let’s be honest, they had definitely been fooled) but those were the facts before the court.

There was only one way Dowling could rule.

However I might believe that trick and deception has been practiced by the prisoner, as I sit here in my capacity of magistrate, I am compelled to decide that the prosecution has failed to prove the case.

And just like that, William H. Mumler was a free man.

Spiritualists touted the verdict as vindication of their beliefs. Skeptics grumbled that it was an unearned victory for superstition over science, with Hickey bemoaning, “Who, henceforth can trust the accuracy of a photograph?” Both side seemed to have missed that Judge Dowling had booted on what they considered the central question.

What Peace and Comfort to the Weary Soul!

This was small comfort to Mumler. He was free, but he’d spent six weeks in jail. Six weeks where he hadn’t been working, but still had to pay rent on a fancy Manhattan storefront he couldn’t use and fees to the most expensive defense lawyer in town. He could try to rebuild, but what would be the point? Every newspaper in New York had used those six weeks to drag his name through the mud.

So he canceled his plans to tour the nation, packed up his stuff, and moved back to Boston. He and Hannah set up a third studio in the basement of her mother’s house, at 170 West Springfield Street.

Spiritualism was approaching its peak, but it had left Mumler behind. The movement’s opinion of Mumler had never been high to begin with, but the trial made him and the art of spirit photography too toxic to touch. He had just enough clients to keep the lights on and put food on the table, but not to thrive. Even so, he managed to make history at least once more.

One day in February 1872 Mumler was finishing up when a woman wearing full mourning dress came through the door, gave her name as “Mrs. Lindall.” This was no Mrs. Lindall, though. This was Mary Todd Lincoln, the widow of the late Abraham Lincoln. (Maybe you’ve heard of him?)

Mrs. Lincoln’s mental health began to deteriorate after the tragic death of her twelve-year-old son Willie in 1862, which sent her into a deep, decades-long depression. Like many people in that death-obsessed age, she turned to Spiritualism for comfort. She liked the idea that Willie was at peace on the other side, and could still be communicated with from time to time. She began patronizing mediums in Georgetown and even organized seances at the White House some 120 years before Nancy Reagan. Honest Abe was no Spiritualist, but was all for anything that made his wife happy. Besides, he found the seances amusing, like a night of dinner theater.

Things only got worse after her husband was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth in 1865, she went completely off the deep end after her 18-year-old-son Tad died suddenly in 1871. Her depression turned into an over-the-top period of mourning that would last for nearly two decades, punctuated by manic-depressive mood swings and crying jags that would last for hours. She became convinced that she was teetering on the edge of financial ruin, while at the same time becoming a compulsive shopaholic and hoarder.

And now she wanted a photo with her late husband.

Mumler claimed that he did not realize who his sitter was until hours later, when he was developing her photograph and saw the Great Emancipator standing behind her. This seems unlikely: she was, after all, the most famous widow in the country. One also thinks he might have been tipped off when, during the sitting, Hannah began channeling the spirit of “Mrs. Lindell’s” deceased son “Thaddeus”, who proceeded to have a long chat with his mother. (On Mary Todd’s end, she didn’t seem to notice or mind that her son had changed his name for some reason — Tad’s full first name as was Thomas.)

The final spirit photograph shows the dumpy figure of Mrs. Lincoln, off center in her black mourning garments. There is a pale, translucent figure standing behind her resting its hands on her shoulders. As is usual in Mumler’s photographs the figure is washed out and indistinct, but it sure looks like Abraham Lincoln if you squint (or maybe just a very good Abraham Lincoln impersonator). Pump up the contrast in Photoshop and it’s astounding how little detail is actually there. It could be any ghostly figure with a big nose, a high forehead, and a beard but no mustache.

Sadly, if the photo had been legitimate, it would be the only known photo of the President and First Lady together. Mary Todd had always refused to be photographed with her husband while she was alive, though no one is whether that was because she was just vain, sensitive about their extreme height difference, didn’t want to seem subservient to her husband, or maybe just angry at him due to various marital difficulties.

Whatever the case was, Mrs. Lincoln was more than overjoyed that she finally had a photo with her husband. According to Mumler, when she saw the finished prints she wept for joy and spoke with longing about joining her loved ones in the Summerland. She paid for her prints and left with a skip in her step.

Now, the photo was supposed to be private, a memento mori for Mrs. Lincoln’s private use. That didn’t stop Mumler from running off a couple hundred more, selling them to anyone who wanted a copy, and letting everyone know he had taken pictures. It was sleazy and manipulative and it did nothing to rehabilitate the public’s opinion of him. So of course it led to a brief career renaissance.

As for Mrs. Lincoln, her increasingly erratic behavior eventually led her only surviving son, Robert Todd Lincoln, to have her placed into an involuntarily conservatorship. That was probably a patronizing overreaction… but this isn’t a story about Mary Todd Lincoln. We’ll get to that story someday, maybe.

Unmistakable Evidence of a Life Hereafter

Mumler made one final attempt to cash in on his infamy in 1875 when he published his memoirs, The Personal Experiences of William H. Mumler in Spirit-Photography. Needless to say, it is not a very good book. Anyone looking for insight into his character or his personal take on the events that had shaped his life was bound to be disappointed. On the other hand, if they were looking for a starf***ing list of all the rich and famous people he had taken photographs of, well, good news!

He and Hannah parted ways in 1879, though they never divorced. After their separation he stopped taking spirit photographs — what was the point? Hannah was the one with all the marketing ability and Spiritualist street cred. He returned to his first love, inventing, and secured several patents for things like electric passenger counters for street cars and improved gas lamps. His most successful invention was the “Mumler process,” a form of electrotyping which finally allowed newspapers to reproduce photographs clearly and easily. It was used by the newspaper industry for decades.

He died on May 16, 1884 alone, forgotten, and poor.

He was a fraud, of course. True believers like to point out that no one was able to replicate his spirit photographs during his lifetime, but that’s not true. Plenty of photographers were able to make similar photographs. What they couldn’t do was observe Mumler in a controlled environment to figure out his exact method, and that was because Mumler refused to be tested. (Our best guess is that he achieved his signature effect with some sort of overprinting.)

Mumler’s photographs were only barely convincing at the time. Today even his most intricate shots are obviously faked; a teenager could easily replicate in a few hours with MS Paint. When spirit photography had a revival in Europe during the Twentieth Century’s interwar period, the photos were far more technically accomplished. Ironically, that only makes them look even more fake because they fell right into the uncanny valley. Modern spirit photographs went the other direction, and are far blurrier and more indistinct than Mumler’s ever were.

In retrospect it seems puzzling that our ancestors fell for such an obvious fraud, but maybe that’s just because media literacy is a skill they hadn’t developed yet. Then again, maybe there’s a more obvious lesson we can take away from this whole affair: that with enough motivation, we can talk ourselves into believing anything.

Supplemental Material

Connections

Irish playwright Dion Boucicault coined the phrase “The Camera Never Lies” in his 1859 play The Octaroon. Boucicault also wrote the 1868 play After Dark, and an 1890 revival of that play provided the first big break for aspiring actress Laura Biggar (“Pleadings from As. What really made Biggar famous, though, was cozying up to a terminally ill millionaire and trying to steal his fortune with a fake pregnancy (“Pleadings from Asbury Park”).

Mumler’s defense lawyer, John D. Townsend, would later represent medium Ann O’Delia Diss Debar (“Spirit Princess”) when she was tried for defrauding elderly lawyer Luther Marsh. That time Townsend didn’t prevail, and Diss Debar went off to Blackwell’s Island.

Spirit photography was used to produce an image of “Little Bright Eyes”, the famous control of medium May S. Pepper (“A Good Thing to Die By”).

There was a resurgence of interest in spirit photography after World War I, only to be thoroughly debunked by a new group of skeptics including Harry Price (“The Fakiest Fake in England”).

Sources

- Barnum, Phineas Taylor. The Humbugs of the World: An Account of Humbugs, Delusions, Impositions, Quackeries, Deceits and Deceivers Generally, In All Ages. New York: Carleton, 1866.

- Carrington, Hereward. The Physical Phenomena of Spiritualism, Fraudulent and Genuine. Boston: Herbert B. Turner, 1907.

- Chéroux, Clément et. al. (editors). The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Coates, James. Photographing the Invisible: Practical Studies in Spirit Photography, Spirit Portraiture, and other Rare but Allied Phenomena. London: L.N. Folwer, 1911.

- Coddington, Ronald S. “The Last Shot: Comforting Spirit.” Military Images, Volume 34, Number 4 (Autumn 2016).

- Cozzolino, Robert (editor). Supernatural America: The Paranormal in American Art. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021.

- Davis, Andrew Jackson. Death and the Afterlife: Eight Evening Lectures on the Summer-Land. Boston: W. White & Company, 1871.

- Emerson, Jason. The Madness of Mary Lincoln. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2007.

- Emerson, Jason. “Mary Lincoln: An Annotated Bibliography Supplement.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Volume 104, Number 3 (Fall 2011).

- Fineman, Mia. Faking It: Manipulated Photography Before Photoshop. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2012.

- Funk, Isaac K. The Widow’s Mite and Other Psychic Phenomena. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1904.

- Funk, Isaac K. The Psychic Riddle. New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1908.

- Hirsch, Robert. Seizing the Light: A History of Photography. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 2000.

- Kaplan, Lois. “Where the Paranoid meets the Paranormal: Speculations on Spirit Photography.” Art Journal, Volume 62, Number 3 (Autumn 2003).

- Kaplan, Louis. The Strange Case of William Mumler, Spirit Photographer. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

- Madloch, Joanna. “Remarks on the Literary Portrait of the Photographer and Death.” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, Volume 18, Number 3 (2016).

- Manseau, Peter. The Apparitionists: A Tale of Phantoms, Fraud, Photography, and the Man Who Captured Lincoln’s Ghost. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2017.

- Morgan, James Appleton. The Law of Literature, Volume I. New York: James Cockroft & Company 1875.

- Mumler, William H. The Personal Experiences of William H. Mumler in Spirit-Photography. Boston: Colby & Rich, 1875.

- Natale, Simon. Supernatural Entertainments: Victorian Spiritualism and the Rise of Modern Media Culture. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016.

- Russell, Alfred Wallace. On Miracles and Modern Spiritualism: Three Essays. London: Trubner & Co., 1881.

- Sidgwick, Eleanor. “On Spirit Photographs: A Reply to Mr. A.R. Wallace.” Proceedings of the Society of Psychical Research, Volume 7 (1891).

- Stolow, Jeremy. “Mediumnic Lights, X-Rays, and the Spirit Who Photographed Herself.” Critical Inquiry, Volume 42, Number 4 (Summer 2016).

- Thompson, Clive. “Pictures That Deceive.” Smithsonian, Volume 52, Number 8 (December 2021).

- Williams, Frank J. and Burkhimer, Michael (editors). The Mary Lincoln Enigma: Historians on America’s Most Controversial First Lady. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2012.

- Williams, William F. (editor). Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience, from Alien Abductions to Zone Therapy. New York: Facts on File, 2000.

- “Doings of the Surreal.” Atlantic Monthly, Volume 12, Number 69 (July 1863).

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: