Unhuman Animals

the Salus-Grady Libel Act of 1903

It started, as many things do, with a think piece.

The highlight of The Atlantic‘s October 1901 issue was “The Ills of Pennsylvania.” The title was meant to be provocative; at the time Pennsylvania was, at least on paper, one of the nation’s most populous, most industrialized, and wealthiest states. Progressive writer Mark Sullivan saw things very differently.

What’s the matter with Pennsylvania? Indeed, she hath more than one disease. But the principal one is, she is politically the most corrupt state in the Union…

Now why? Why is Massachusetts, with her native-born in a numerical minority, the best governed commonwealth in the union, while Pennsylvania, with her native born in large majority, wallows in corruption?

The first answer is, because Pennsylvania has an overwhelming Republican majority. But this is too obvious to be good… No, you must look deeper than the tariff for the cause of Pennsylvania’s corruption. In the long run, the politician is a correct representative of the people. You can’t have corrupt politicians without some moral deficiency in the mass of the voters. And that is precisely what you have in Pennsylvania.

Sullivan, “The Ills of Pennsylvania”

Sullivan blamed the sorry state of Pennsylvania on one man: Senator Matthew Stanley Quay, the de facto head of the local Republican Party. Quay ran the Commonwealth with an iron fist and kept himself and his cronies in power through rampant voting fraud, patronage, and bribery.

“The Ills of Pennsylvania” was well-researched and well-written. No one could deny that it exposed a massive web of graft and corruption. And yet it did not harm Senator Quay at all. He was simply too powerful, and his all-encompassing political machine shielded him from any consequences for his misdeeds. What could one journalist alone do against such a foe?

Of course, that did not stop those who were broadly supportive of the status quo from rushing to the defense of Senator Quay. Most of these white knights were already Quay’s co-conspirators, and those who weren’t were desperately trying to suck up to him.

One who did not fall into either category was Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker, a distant cousin of Quay’s, and what passed for a public intellectual back in those days. He was a judge, lawyer and historian; former president of the Law Academy of Philadelphia and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania; a trustee of the University of Pennsylvania; founder of the Pennsylvania Society of the Sons of Revolution. He was known for his wisdom, erudition, good breeding, and his blunt honesty.

At least that’s how Pennypacker saw himself. In actuality he was a rich idiot, a man of utter mediocrity whose success was not attributable to talent or hard work but to inherited wealth and social connections. To be folksier about it, he was born on third base but was convinced he’d hit a triple. Like many men in such circumstances, Pennypacker was unwilling or incapable of conceiving how anything which personally benefitted him could ever be bad. When that naive faith was challenged he had a bad habit of responding with irrational and all-consuming rage.

Though Pennypacker was a judge, he himself was wealthy and socially connected and also such small potatoes that he had no first-hand experience with the rampant corruption Sullivan had uncovered. Therefore, he concluded, it must not exist.

Pennypacker penned a series of passionate articles defending the status quo. (Passionate may be an overstatement. Pennypacker’s writing is like a bad textbook: pedantic, droning, and soporific.) These caught Senator Quay’s attention.

Though Sullivan’s articles had not hurt Quay politically, it had caused him to engage in a bit of introspection. Not that he ever contemplated changing his ways, mind you, but enough to make him concerned about optics. He began looking for ways to make the Commonwealth seem less corrupt than it actually was.

And that’s why in 1902 Senator Matthew S. Quay decided to make Judge Samuel W. Pennypacker the Republican nominee for governor.

In many ways Pennypacker was an ideal puppet. He had no obvious connections to the machine and its corruption; as a staunch supporter of the status quo he could be trusted to not go off-script; and if he ever did start to question the status quo he was easily manipulated if you knew how to stroke his ego.

Perfect example: Pennypacker was reluctant to accept the nomination, but acquiesced when Quay flattered him it was a reward for his scrupulous honesty and moral rectitude. He wrote in his autobiography that the nomination “came to me without the lifting of a finger, the expenditure of a dime, or the utterance of a sigh.”

Which is, in some sense, true. Pennypacker didn’t spend any of his own money on the campaign, and could barely be bothered to participate beyond writing grandiloquent letters to the editor. Quay was the one who spent all the money, greased all the palms, and mobilized all the troops.

The Ungentlemanly Art

Quay and Pennypacker did not realize the tremendous gift they had just handed Pennsylvania’s political cartoonists.

Political cartoons have a long and noble history. Ever since man first learned to draw, he he has drawn unflattering caricatures of those in power.

American political cartoons date back to some dude named “Benjamin Franklin.” Admittedly, Franklin didn’t draw them, but he did commission other people to do it for him. He knew what he was doing, though. Franklin’s most famous cartoon is one that Paul Revere whipped up for him in 1754, a woodcut of a chopped-up snake with the caption “Join or Die.” Despite Franklin’s tremendous success, for more than a century American political cartoons instead chose to follow a European template, placing an emphasis on classical draftsmanship that was hard to reproduce and obscure allegory that often required long explanations.

The art form finally figured it out during the Gilded Age, thanks to the invention of quick methods of mechanical reproduction and the development of artists who combined graphic boldness with a combative pugnaciousness. Think of Thomas Nast, whose simple cartoon of Boss Tweed with a moneybag for a head is as impactful today as it was in the 1870s.

It didn’t hurt that the contentious and polarized politics of the day gave them plenty of material to work with. Material like Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker.

In many ways the judge was a political cartoonist’s dream. He was easy to caricature: squat with no neck; disheveled head hair but a meticulously groomed pointy beard; a weird predilection for wearing riding boots. He was even easier to satire, thanks to his distinctive grandiloquent and archaic speech patterns, and his utter inability to take a joke.

It did not help that he was also up against some of the most talented cartoonists in the country.

Thomas Wanamaker, the publisher of Philadelphia’s North American, was mildly progressive and virulently anti-Quay. He had recently lured cartoonists Charles Nelan and Walt McDougall away from the New York Herald and New York World respectively, and did not hesitate to turn them loose on his enemies.

The North American ran cartoons viciously attacking Quay and Pennypacker nearly every day. Nelan and McDougall did not hold back; they were not just mean but cutting and insightful. They depicted the candidate as a vainglorious parrot who could only repeat Quay’s words; as a clueless pirate swearing an oath to the felonious Captain Quay, and as a maid “filling her bucket at the well of political ambition.”

Nelan’s parrot cartoon, which ran on October 19, really got under Pennypacker’s skin. The judge began furiously attacking the North American as “a worthless advertising sheet, miscalled a newspaper, which hires needy young artists to pervert their art.” The spluttering response virtually guaranteed a return to the motif. In the weeks before the election the political cartoons appeared right on the front page, many of them featuring Pennypacker as a parrot.

In the end, they made no difference. On November 4, Pennypacker cruised to victory with 54% of the popular vote.

At this point, a seasoned politician would have let the matter drop. Pennypacker was not a seasoned politician. On January 20, 1903 he spent a good chunk of his very long inaugural address attacking the freedom of the press.

There is no more dangerous public vice than the prevalent affectation of disrespect for those who are engaged in the performance of the work of the cities, the Commonwealths and the nation… There was a time when proper deference was shown even to those officials lowest in authority and the cultivation of a like spirit is a much-needed virtue…

The doctrine of the liberty of the press, conceived at a time when it was necessary to disclose the movements of arbitrary power, has become in recent days too often a cover for base and ignoble purposes… Sensational journals have arisen all over the land… and they have thriven by propagating crime and disseminating falsehood and scandal, by promulgating dissension and anarchy, by attacks upon individuals and by assaults upon government and the agencies of the people. They are a terror to the household, a detriment to the public service, and an impediment to the courts of justice. It would be helpful and profitable to reputable journalism if they could be suppressed.

Samuel W. Pennypacker, inaugural address, January 20, 1903

Big Pus(s)ey

Big Pus(s)ey

Now, if you are a politician who feels like you are being unfairly targeted by political cartoons, you have a few options.

The best course of action would be to develop a thicker skin and a more gracious sense of humor, and lean into it. This was the approach favored by Teddy Roosevelt, who always enjoyed a good chuckle and was a bit of a human cartoon anyway.

Maybe you’re thin-skinned and don’t want to learn how to take a joke. In that case you can sue the cartoonist for libel. Unfortunately for you, you are a public figure so unless the cartoonist is engaging in the most egregious character assassination, they will be able to use the First Amendment as an absolute defense.

You could try to use your power and influence to get the cartoonist fired. The problem is that any newspaper publishers who can be influenced this way would have never published the offending cartoon in the first place. Even if you could buy the publisher off somehow, his rivals would report on the obvious quid pro quo and land you in hot water.

You could cut out the middleman and bribe the cartoonist directly. They are a mercenary lot, but believe it or not, they actually do have principles. In the best case scenario your offer will be ignored. In the worst case scenario they will screw around with you first. Once Thomas Nast’s enemies offered him a fellowship to study art in Europe in exchange for quitting. Nast spent months negotiating increases in the amount of the bribe, before rejecting the offer with the excuse that he “just wanted to see how high you could go.”

Finally, you could try to pass some legislation to make your particular bugaboo illegal. This is the sort of thing you are already supposed to be doing as a politician, so it won’t take time out of your day. In the long term you will probably run into First Amendment issues, but if you’re lucky you can crush your enemies before they have a chance to mount that defense.

Three guesses which option most politicians go for. First two don’t count.

On January 28 1903, only a week after the inauguration, freshman representative Frederick Taylor Pusey of Landsdowne, Delaware County introduced a bill in the house prohibiting:

…any cartoon or caricature or picture portraying, describing or representing any person, either by distortion, innuendo or otherwise, in the form or likeness of beast, bird, fish, insect, or other unhuman animal, thereby tending to expose such person to public hatred, contempt or ridicule.

Publications containing such cartoons would be illegal to produce or sell in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Violations would be a misdemeanor and punishable by a $1,000 fine and/or two years in prison.

Pusey appears to have been acting on his own volition, as an attempt to suck up to Senator Quay and Governor Pennypacker.

Some cartoons are very funny, of course, but these pictures in which human beings are represented as animals and birds are bestial, you know. They’re degrading. I don’t think they ought to be allowed.

“Pusey laughed at.” Harrisburg Independent, 28 Jan 1903

He, of course, had just placed himself in the crosshairs of the Commonwealth’s political cartoonists. Nelan depicted the representative as a “pus(s)ey cat” and others as a pus(s)ey willow or Pus(s)ey-in-Boots.

McDougall got in the best jabs, with a cartoon that caricatured Republicans without turning them into animals; the short, squat Pennypacker became a stein, and the thin, ailing Quay became a dying oak. McDougall’s mocking editorial explained:

[Pusey] should have included more than the animal kingdom alone, for we have an ample field in the vegetable if not even the mineral field. Every cartoonist has a Noah’s Ark full of worn, broken and decrepit animals, bugs and such, but the fresh vegetable field is untouched. What chances of caricature lie in the tomato, the string bean, the cucumber, the onion and the leek cannot be guessed.

quoted in “Drawn to Extremes: the Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons

Pusey revised his bill to address some of the minor criticisms, such as softening the prohibition on printing and selling cartoons by explaining the prohibition only applied to publications headquartered in Pennsylvania. (He did not seem to realize that created a whole other set of Constitutional issues.)

If he thought that would shield him from mockery, he was sorely mistaken. When Pusey rose to present the revised bill on February 4, other legislators mocked him by meowing and hissing.

Newspaper editorials also took aim at the young idiot.

If Mr. Pusey objected to such caricatures on the ground that they were unjust or cruel to other animals than man, his position would be more capable of defense. But man, petty man, that comparative newcomer and upstart in the world, has no reason to exalt himself at the expense of his ancestors and cognates. His genealogical tree is too well known. His moral and mental, as well as physical analogy or identity with the beasts and fowls of the air is undeniable… (New York Sun, 2 Feb 1903)

If there were a moral issue in the matter it would be different, because it is perfectly proper for a state to compel its citizens to live rightly, even if the people across the boundary lines do not. But so far as we can see nothing is involved except the feelings of a few nasty politicians who have been made to realize the power of cartoons in a political campaign by actual experience. (“The anti-cartoon bill.” Harrisburg Independent, 5 Feb 1903.)

It is a good thing to laugh and all people need something to stir their risibility… No man is really injured by being portrayed as an ‘unhuman animal.’ That sort of thing is not an attack upon his character or standing in the community and cannot lower him in public esteem… Let the people have their fun and the cartoonists earn their salaries. (“The anti-cartoon bill.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 16 Feb 1903.)

The bill’s third reading was long-delayed but it finally came up again in late March.

Very few people seemed to be taking it seriously. The consensus was that legislature was humoring Pusey and his “inability to distinguish between legislation and foolishness.” (Harrisburg Independent) The idea seemed to be they would let him introduce his bill, score some quick points by dunking on him, and then allow him to save face by withdrawing.

Others were not so sure about that. Representative Thomas V. Cooper, a former newspaper editor, warned that there were still powerful people intent on moving ahead with the anti-cartoon bill, the Constitution be damned.

The Press Muzzler

Cooper was both right and wrong.

Quay and his machine were still busy drawing up legislation. In early April, while Pusey’s bill was languishing in committee, representatives John C. Grady and Samuel W. Salus simultaneously introduced two separate bills in the House and Senate, respectively.

The bills, were, shall we say, suspiciously similar. They were not anti-cartoon bills, but general anti-press bills. They required newspapers to publish the names and addresses of their publishers and editors. They made those persons and their employees and contractors personally liable for libelous material that appeared in their publications. They also lowered the standard for libel to the rather low bar of “mental suffering.”

There was only one significant difference between the two bills. Salus’s Senate bill set the penalty for violations at the punitive rate of $1,000 per violation. Grady’s House bill set the penalty at the extremely punitive rate of $1 per copy published. (Not distributed or read, mind you, just published.)

Newspaper editors around the Commonwealth lost their shizz. They published panicked editorials attacking Quay as a tool, a professional lobbyist, a would-be Napoleon, and a Judas.

Representative Cooper made a more level-headed and reasoned argument:

[The Grady bill] is an attempt to chain the human mind and to put shackles upon thought and it would be found that this is impossible now as it has always been… Men of mind will rise up and protest against this infamy…

I believe in cartoons. I would give the liberty to the cartoonist to picture our governor as a goldenrod, with the roots firmly planted in his ancestral boots, the goldenrod so firm that he could hold it over us when we sent him vicious and foolish legislation…

Let our behavior be such that the cartoonist must treat us kindly. If it be otherwise, the fault is not all with the newspapers or the cartoonists.

Many legislators felt the same way, even the Republicans. They could sense that the Salus and Grady bills were not winners. The public seemed to be siding with the newspapers and found them petty and vindictive.

The problem was that the two people who did like the bills were Senator Matthew S. Quay and Governor Samuel W. Pennypacker. They went to work behind the scenes and started whipping recalcitrant legislators into line. In an extraordinary measure the House replaced the text of its Grady bill with the complete text of the Senate’s slightly more popular Salus bill, without going through the ordinary reconciliation process. The combined Salus-Grady Bill was put to a vote. All but 22 Republican legislators held their noses and voted for a bill they all knew was a stinker. That was more than enough.

The speed at which this was accomplished implied there was something fishy going on. Salus and Grady had introduced their separate bills on Holy Wednesday, April 8. They were debated, combined, voted on, and put on the governor’s desk before noon on Good Friday, April 10. Under normal circumstances the legislature would get absolutely nothing accomplished in the week before a major holiday.

Not wanting to make it look like the fix was in, Pennypacker announced he would not sign the Salus-Grady Bill until he had held a public hearing on it. On April 21 more than 300 newspapermen showed up at the capital to argue against the bill. They were joined by clergymen, who felt that the erosion of one First Amendment right would inevitably lead to the erosion of all First Amendment rights. (They were also joined by Socialists, though the newspapermen just wished they would go away.)

Any hopes that Pennypacker might veto the bill were quickly dashed. The governor was polite, but dismissive throughout the hearing. It was clear he viewed this as a pro forma matter to avoid the appearance of impropriety, and nothing else.

To be fair, anyone thinking Pennypacker might be persuaded to change his mind was deluding themselves. Why in the world would he veto something that gave him everything he had asked for in his inaugural address?

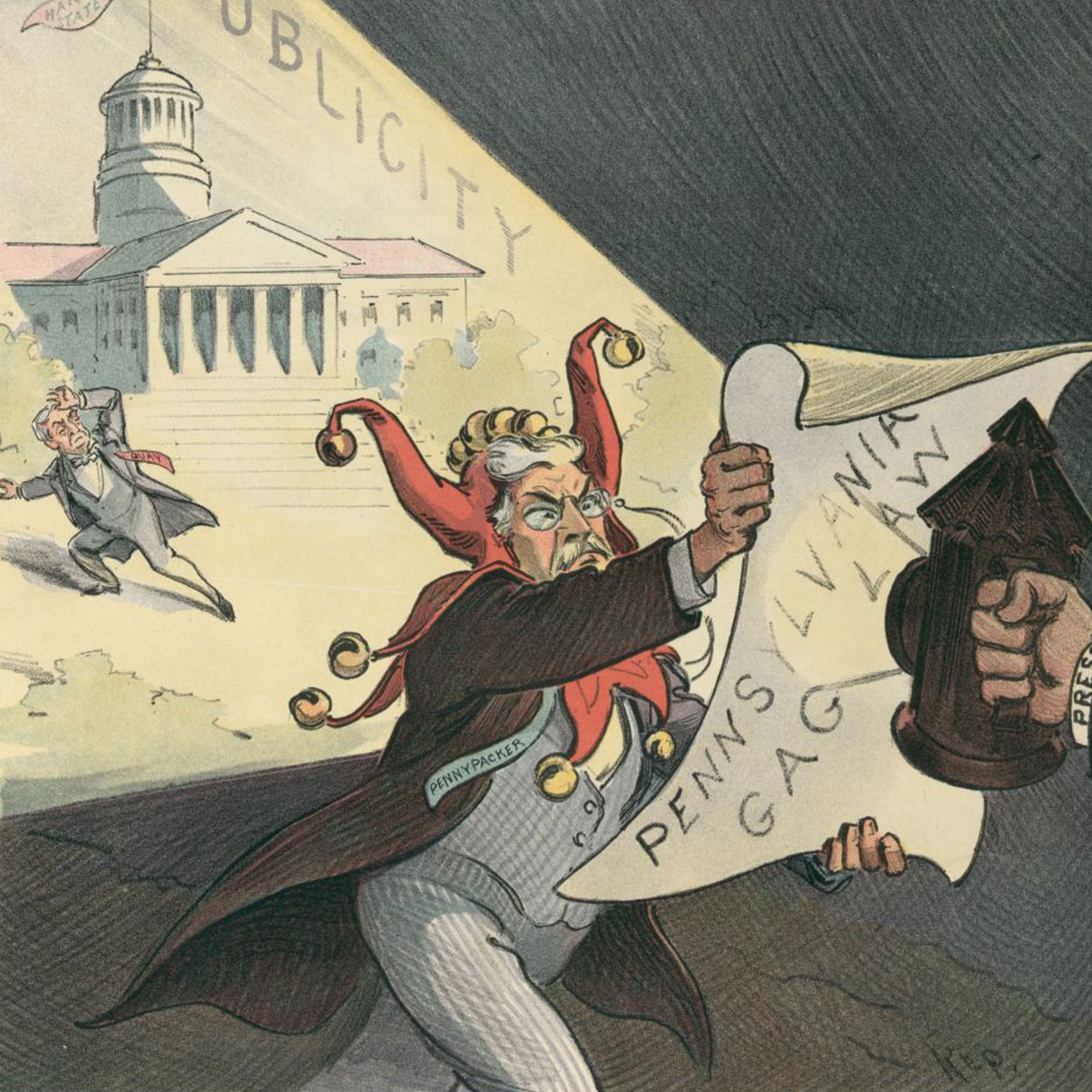

The North American made a last ditch tempt to make the Salus-Grady “press muzzler” political poison. Nelan turned in a defiant cartoon, depicting Pennypacker as an angry dwarf unsuccessfully trying to jam a printing press, with the caption, “But the press didn’t stop… and it won’t.” More than 75 out-of-state newspapers sent in editorials and cartoons harshly criticizing the bill. Even the New York Post chimed in…

It is late in the day for public men in this country to imagine that they may or should enjoy immunity from criticism… If they are so thin-skinned, their remedy is private life.

Pennypacker would not be persuaded. He signed the Salus-Grady Bill into law on May 12, 1903. He used his ridiculously long signing statement (nearly five times longer than the actual act) to take a victory lap.

A mayor of our chief city has been called a traitor, a senator of the United States has been denounced as a yokel with sodden brain, and within the last quarter of a century two Presidents of the United States have been murdered, and in each instance the cause was easily traceable to inflammatory and careless newspaper utterance. A cartoon in a daily journal of May 2nd defines the question with entire precision. An ugly little dwarf, representing the Governor of the Commonwealth, stands on a crude stool. The stool is subordinate to and placed alongside of a huge printing press with wheels as large as those of an ox-team, and all are so arranged as to give the idea that when the press starts the stool and its occupant will be thrown to the ground. Put into words, the cartoon asserts to the world that the press is above the law and greater in strength than the government. No self-respecting people will permit such an attitude to be long maintained. In England a century ago the offender would have been drawn and quartered and his head stuck upon a pole without the gates. In America to-day this is the kind of arrogance which “goeth before a fall”…

If such abuse of the privileges allowed to the press is to go unpunished, if such tales are permitted to be poured into the ears of men, and to be profitable, it is idle to contend that reputable newspapers can maintain their purity… One rotten apple will ere long spoil all in the barrel. The flaring headlines, the meretricious art, the sensational devices and the disregard of truth, in time will creep over them all…

Were a stranger from Mars by some accident to read our daily press, he would conclude that the world is inhabited by criminals and governed by scoundrels. It is sad to reflect that some historian of five hundred years hence, misled by what he reads, will probably study the statesman whom we know to be able and strong, generous and kindly, keeping his promises and paying his debts, and depict him with the features of an owl and the propensities of a Nero or Caligula…

When we walk the streets or drive a horse, or light a fire, or make a shoe or build a house, we must take care that we do not cause harm to others. It applies to the gatherer of garbage. Why should it not apply to the gatherer of news?

Hired Outcasts

The North American, predictably, went into mourning. The editorial page suggested the Commonwealth needed a new coat of arms to go along with tyrannical new law, suggesting the new heraldry should include an impaled cartoonist’s head, a gag, a muzzle, a dwarf on a stool, a pussy cat, and a jackass in knee-high boots. This would, be of course, combined with a change of the state motto from “Virtue, Liberty, and Independence” to “Vanity, License, and Impudence.”

Nelan took it a bit more personally, since Pennypacker had alluded specifically to one of his cartoons in the signing statement and called the artist a “hired outcast.” He immediately took advantage of the new law by threatening Pennypacker with a libel suit, claiming that it had caused him mental suffering and since a signing statement was optional it could not therefore be protected as an official act. Pennypacker tried to brush it off by noting, “You are entirely correct in saying that your personality has never come under my observation and I may add that I am entirely unconscious of ever having made, in any way, any reference to you.” Which is ridiculous, because his word had been published in the newspaper where everyone could see.

Other than that, though… nothing happened.

The North American‘s crusade had failed to make the law unpopular enough for Pennypacker to veto it, but it had made it so unpopular that no one other than Pennypacker was willing to enforce it. There were a few threats — the Connellsville town council threatened to sue the Connellsville Daily News for causing “mental suffering” — but those threats never managed to turn into actual lawsuits.

Most newspapers did play it safe by complying with the least onerous part of the law, publishing the names of their publishing and editorial staff.

The only person who seemed to like the press muzzler was Pennypacker. In a 1904 banquet honoring Pennsylvania’s junior senator, Boies Penrose, he declared:

Pennsylvania alone, of all the American Commonwealths, has recognized the evils which result from the degeneracy of the modern press, and she alone has had the courage to adopt a measure which looks to the correction of those evils.

The audience sat on its hands for that one. He spent much of 1904 and 1905 calling for even harsher restrictions on the press.

The Press Didn’t Stop

By the time the 1906 gubernatorial election rolled around things in the Commonwealth looked very different.

Both Charles Nelan and Matthew Quay had died in 1904, the former suddenly and the latter after long years of decline. After Quay’s death his machine fractured into competing factions, none of whom had any love for the overbearing and officious Pennypacker. He was not renominated for the post, and was succeeded by Edwin Sydney Stuart, “the Governor Who Cares.” (I suppose one of the perils of being a political outsider is lack of institutional support. Pusey also lost his bid for re-election.)

Pennypacker’s legacy as governor was decidedly mixed. He signed into law one of the Commonwealth’s first Child Labor Acts, appointed the state’s first Commissioner of Forestry, and founded the State Museum of Pennsylvania. On the other hand, he also oversaw the construction of the new state capitol, a process so full of corruption and graft that several people went to jail for it. He continued to think of the Salus-Grady Act as one of his crowning achievements. In his Autobiography of a Pennsylvanian he praised the bill and showed no sign of introspection or remorse…

In fact, the doctrine of the liberty of the press is an anachronism which has become harmful and the time has come when it ought to be discarded from our constitutions and laws. Like monarchy and priestcraft, it once answered a good person… Those times have gone.

The rest of the state continued to think otherwise. The basic line on the law was laid down by the Harrisburg Independent…

No man who believes in the policies asserted in the Salus-Grady libel law is fit to represent a liberty-loving constituency. (Harrisburg Independent)

At the start of the 1907 legislative session, freshman legislator Robert P. Habgood of McKean County, another former newspaperman, introduced a bill that would repeal most of the Salus-Grady Act while keeping the one part everyone seemed to like (requiring public notice of who the publishers and editors were). It sailed through the legislature in nearly unanimous votes and was signed into law without delay by Governor Stuart.

In the end, the Pittsburgh Dispatch got in the final word, claiming that the Commonwealth had finally proved…

The pen is not only mightier than the sword, but that it prevails over the muzzle and the spirit of the inquisition. (The Pittsburgh Dispatch)

Connections

If the name Samuel Pennypacker seems familiar, that’s because his other signature achievement was completing the construction of the Pennsylvania Capitol (“Cloud Dongs”), a process that so rife with graft that several people went to jail and which Pennypacker defended as 100% legitimate, how dare you even suggest otherwise, don’t you know he’s a man of honor.

If Frederick Pusey’s district of Lansdowne seems familiar, that may be because it’s my hometown. Or maybe it’s because we did an episode about the town’s legendary radioactive house, where a college professor used to enrich radium in the basement as a home business. (“The Hot House”)

Sources

- Dewey, Donald. The Art of Ill Will: The Story of American Political Cartoons. New York University Press, 2007.

- Dorman, D. “When Cartoonists Were Criminals.” Historical Society of Pennsylvania. https://hsp.org/blogs/fondly-pennsylvania/when-cartoonists-were-criminals Accessed 10/17/2024.

- Hess, Stephen and Kaplan, Milton. The Ungentlemanly Art: A History of American Political Cartoons. McMillan, 1975.

- Hutto, Cary. “The 23rd Gov. of PA tried to criminalize political cartoons. Who was he?” Historical Society of Pennsylvania. https://hsp.org/blogs/question-of-the-week/the-23rd-gov-of-pa-tried-to-criminalize-political-cartoons-who-was-he Accessed 10/17/2024

- Keppler, Udo J. “It can’t be shut off.” Theodore Roosevelt Center. https://theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o277283 Accessed 10/17/2024.

- Lamb, Chris. Drawn to Extremes: The Use and Abuse of Editorial Cartoons. Columbia University Press, 2004.

- Lordan, Edward J. Politics, Ink: How America’s Cartoonists Skewer Politicians, from King George III to George Dubya. Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

- Pennypacker, Samuel Whitaker. The Autobiography of a Pennsylvanian. John C. Winston Company, 1918.

- Piott, Steven L. “The Right of the Cartoonist: Samuel Pennypacker and the Fredom of the Press.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Volue 55, Number 2 (April 1988).

- Sullivan, Mark (as “A Pennsylvanian”). “The Ills of Pennsylvania.” Atlantic Monthly, October 1901.

- Woodruff, Clinton Rogers. “Some Results of the Philadelphia Upheval of 1905-1906.” American Journal of Sociology, Volume 13, Number 2 (September 1907).

- “Ep. 71- Salus-Grady Libel Law.” On The Potcast. https://onthepotcast.podbean.com/e/ep-71-salus-grady-libel-law/ Accessed 10/17/1024.

- “Salus-Grady libel law.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salus-Grady_libel_law Accessed 8/22/2024.

- Williamson, Henry C. “Back in the Past.” Cartoons Magazine, Volume 3, Number 6 (June 1913).

- “Anti-cartoon bill.” Harrisburg Daily Press, 27 Jan 1903.

- “Bill dropped by committee.” Pittsburgh Press, 27 Jan 1903.

- “Committee reports held.” Pittsburgh Press, 28 Jan 1903.

- “Pusey laughed at.” Harrisburg Independent, 28 Jan 1903.

- “Governor signs his first bill.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 Jan 1903.

- “Will have fun with ‘Pussy.'” Harrisburg independent, 29 Jan 1903.

- “Governor urges apportionment.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 Jan 1903.

- “‘Pussy’ goes home.” Harrisburg Independent, 30 Jan 1903.

- “Men and animals.” Harrisburg Independent, 3 Feb 1903.

- “‘Pussy’ Pusey’s bill passed second reading.” Harrisburg Independent, 4 Feb 1903

- “Pusey anti-cartoon bill mildly amended.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 4 Feb 1903.

- “The anti-cartoon bill.” Harrisburg Independent, 5 Feb 1903.

- “Pusey hard at work.” Harrisburg Independent, 6 Feb 1903.

- “Durham may resign soon.” Pittsburgh Press, 10 Feb 1903.

- “Pusey once more makes himself ridiculous.” Harrisburg Independent, 10 Feb 1903.

- “The anti-cartoon bill.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 16 Feb 1903.

- “Anti-cartoon bill to come up.” Harrisburg Independent, 23 Mar 1903.

- “Await visit of governor.” Pittsburgh Press, 23 Mar 1903.

- “War on Pusey bill.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 31 Mar 1903.

- “A throttling libel bill.” Harrisburg Independent, 7 Apr 1903.

- “Senate and house resume sessions.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 Apr 1903.

- “Senate pulling fangs of the new libel bill.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 8 Apr 1903.

- “Quay’s gag of newspapers.” Pittsburgh Press, 8 Apr 1903.

- “The attempt to push libel law through fails.” Pittsburgh Press, 8 Apr 1903.

- “Big battle is now on over Salus libel bill.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 9 Apr 1903.

- “Libel Bill passed by the senate.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 9 Apr 1903.

- “House again obeys order.” Harrisburg Independent, 10 Apr 1903.

- “Libel law now up to the governor.” Pittsburgh Press, 10 Apr 1903.

- “Senators defy protests; pass press muzzler.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 10 Apr 1903.

- “A hearing on the libel bill.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 11 Apr 1903.

- “Governor gives halt to the press muzzler.” Herald, 11 Apr 1903.

- “Libel bill hearing April 21.” Harrisburg Independent, 11 Apr 1903.

- “Salus bill is sent to the governor.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 Apr 1903.

- “Direct blow at religion.” Pittsburgh Press, 12 Apr 1903.

- “A chance yet still allready.” Evening Record, 13 Apr 1903.

- “Filing protests against muzzler.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 17 Apr 1903.

- “Judge Miller on libel bill.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 Apr 1903.

- “For the sake of freedom.” Pittsburgh Press, 20 Apr 1903.

- “Pulpit denounces the press muzzler.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 20 Apr 1903.

- “Newspaper men fight libel bill.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 21 Apr 1903.

- “Rally in mighty muzzler protest.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 21 Apr 1903.

- Goshorn, L.K. “Iniquities of the libel bill are laid bare.” Pittsburgh Press, 22 Apr 1903.

- “Signing of libel bill is likely.” Harrisburg Independent, 5 May 1903.

- “Press muzzler is approved.” Harrisburg Independent, 13 May 1903.

- “Press muzzler badly jolted by newspaper men.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 May 1903.

- “Governor is called by cartoonist.” Pittsburgh Post, 16 May 1903.

- “Pennypacker remains silent.” Harrisburg Independent, 16 May 1903.

- “Libel law may be boomerang.” Pittsburgh Press, 17 May 1903.

- “Party men denounce press muzzler.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 May 1903.

- “Called cartoonist an outcast unconsciously.” Harrisburg Independent, 19 May 1903.

- “First paper to be sued.” Harrisburg Independent, 21 May 1903.

- “Denounced the press muzzler.” Harrisburg Independent, 23 May 1903.

- “Socialists condemn the press muzzler.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 1 Jun 1903.

- “Pique and piracy back of libel law.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 10 Jun 1903.

- “Press league hits state libel law.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 24 Jun 1903.

- “Now it’s bullfrogs vs. press muzzler.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 17 Jul 1903.

- “Governor defends muzzler.” Harrisburg Independent, 30 Jan 1904.

- “The ‘muzzled press.'” Harrisburg Telegraph, 24 Mar 1904.

- “Press muzzlers condemned.” Harrisburg Independent, 29 Mar 1904.

- “Too few jails for Penny’s impugners.” Harrisburg Independent, 5 Nov 1904.

- “Cartoonist Nelan dead.” Scranton Truth, 22 Nov 1904.

- “Governor urges park extension.” Harrisburg Independent, 3 Jan 1905.

- “New libel bill is presented.” Pittsburgh Press, 24 Jan 1905.

- “Goehring’s libel bill.” Harrisburg Independent, 15 Feb 1905.

- “Salus-Grady repeal.” Pittsburgh Press, 29 Jun 1906.

- “Press muzzler’s repeal advised.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 14 Feb 1907.

- “The press muzzler is to be repealed.” Harrisburg Independent, 14 Feb 1907.

- “Down goes press muzzler unanimous in the house.” Harrisburg Independent, 28 Feb 1907.

- “Is a successor to Salus-Grady law.” Harrisburg Independent, 20 Mar 1907.

- “New press-muzzler bill is regarded as joke.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 21 Mar 1907.

- “Press muzzler to be repealed without delay.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 Apr 1907.

- “Senate repents and passes bill.” Harrisburg Independent, 16 Apr 1907.

- “Referendum chocked by machine’s gag.” Pittsburgh Post, 2 May 1907.

- “Press emancipator.” Editor and Publisher, 11 May 1907.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: