The Prophet of the Pacific

from San Francisco to Honolulu to Bombay, first class all the way

And Moses went up from the plains of Moab unto the mountain of Nebo, to the top of Pisgah, that is over against Jericho. And the Lord shewed him all the land of Gilead, unto Dan, and all Naphtali, and the land of Ephraim, and Manasseh, and all the land of Judah, unto the utmost sea, and the south, and the plain of the valley of Jericho, the city of palm trees, unto Zoar. And the Lord said unto him, This is the land which I sware unto Abraham, unto Isaac, and unto Jacob, saying, I will give it unto thy seed: I have caused thee to see it with thine eyes, but thou shalt not go over thither. So Moses the servant of the Lord died there in the land of Moab, according to the word of the Lord. And he buried him in a valley in the land of Moab, over against Bethpeor: but no man knoweth of his sepulchre unto this day… And the children of Israel wept for Moses in the plains of Moab thirty days: so the days of weeping and mourning for Moses were ended.

Deuteronomy 34:1-6,8

The Word of the Lord

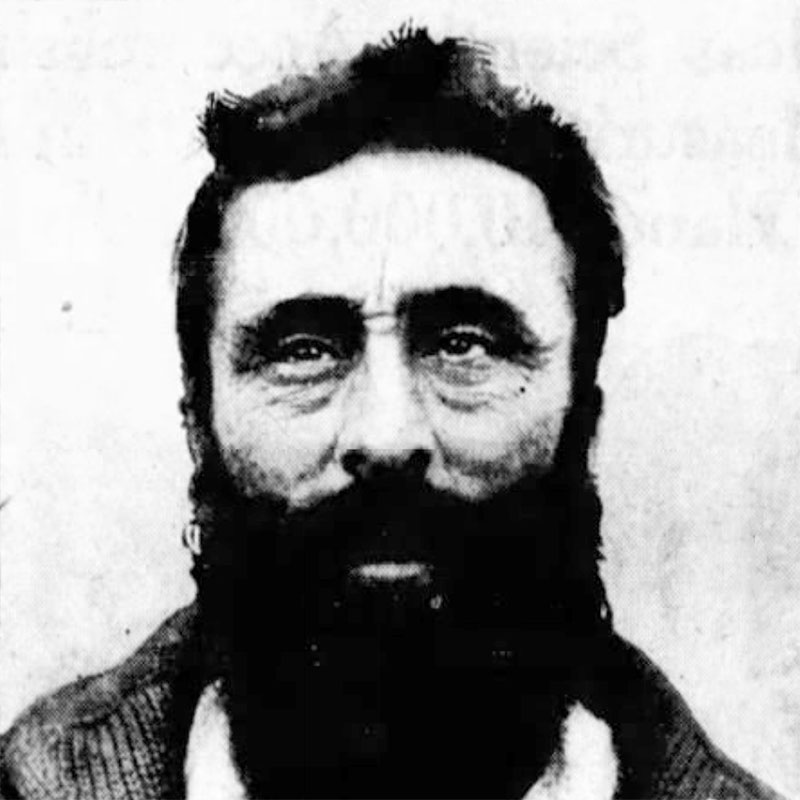

Ira Colver Sparks was born in Peru, Indiana on December 10, 1886.

By all accounts, he had an unremarkable childhood. Neighbors remembered him as “inoffensive youth of no particular promise” who loved reading his Bible. Ira grew into an inoffensive adult of no particular promise. He found employment as a humble carpenter doing odd jobs for the folks around town — fixing chicken coops, re-hanging screen doors, stuff like that.

When Ira C. Sparks turned 35, he had a mid-life crisis.

Now, for most men a mid-life crisis might involve a sports car, frosted tips, and a girlfriend half their age. Ira’s mid-life crisis was a little different. The Lord our God spoke to him and told him to take up the work of Moses, travel to the Holy Land and convert the heathen.

Well, a call like that cannot be ignored. So Ira Sparks threw everything he had into a beat-up old suitcase and hitched started hitching his way to the coast.

When he reached the Pacific Northwest, he took a job at a lumber camp for a few months, saving every penny he earned. In December 1922, with a wallet full of cash, Sparks took his passport and headed down the coast to San Francisco to buy a steamship ticket to Bombay.

Which turned out to be way more expensive than he thought.

But Ira C. Sparks was nothing if not resourceful. And it helped that God showed him the solution to his dilemma. If he couldn’t make his way to India as a passenger, he would make his way… as freight. He scrounged up some scrap wood and built himself a box. Not a very big box, mind, you, only about 30 cubic feet. He couldn’t stand up in it, but it was big enough that he could sit down. Or lie down, if he bent his legs. It had a secret panel he could use to slip in and out undetected. And it also had a small pantry filled with potted meat, crackers, and 15 gallons of water.

Sparks managed to convince the Toyo Kisen Kaisha Steamship Company company to take the box, which he claimed held 548 lbs. of “personal effects” valued at $15. The total charge was $24.42.

Stevedores loaded the box onto the good ship Taiyo Maru on January 2, 1923, There was a brief debate about where to put the dang thing, because it was leaking water. Eventually they decided to just throw it into the ship’s silk room. They figured if there was a problem, the stevedores at the next port of call could deal with it.

Ira C. Sparks spent five days in his box as the Taiyo Maru made its way from San Francisco to Honolulu. Five days confined in a tiny box. In near-total darkness. On a rocking boat. Barely able to shift positions, with his joints and muscles groaning in complaint. Afraid to make even the smallest noise, lest he be discovered. With nothing to eat but SPAM and captain’s wafers and water stored in old oil cans. With nothing to do but sit and be alone with his thoughts.

Well, his thoughts and five days worth of excrement.

Needless to say, five days was about all Sparks could take.

The final straw was when he overheard the Taiyo Maru‘s crew talking about moving the box to the lowest hold for the next leg of the journey. That terrified Sparks, who thought he would die alone down there in the dark. So he decided to take a stroll and weigh his options.

He was spotted almost immediately by the crew, who were flabbergasted to see a strange man on board five days out from port. Sparks just gave them a sheepish grin and explained himself.

I’m going to the Holy Land to take up the work of Moses.

When the Taiyo Maru arrived in Honolulu on January 8, 1923 they turned Ira C. Sparks over to Sheriff Charles H. Rose. The sheriff was not entirely sure what to do with Sparks.

- He was an American citizen, so he wasn’t an immigrant.

- He wasn’t a passenger because he’d arrived as freight.

- But he wasn’t freight either, because he was a human being.

- He couldn’t be jailed for vagrancy, because he’d brought his carpenters’ tools with him and had $15 in his pocket.

- And he couldn’t be returned to sender, because there were still outstanding custom duties on his “personal effects.”

The TKK Steamship Company offered to take Sparks back to San Francisco, but rescinded that offer when they learned there’d be a $200 fine for knowingly taking a passenger on a cargo vessel. In the meantime Sparks was getting three square meals a day in jail, costing the good people of Honolulu County the princely sum of $1/day.

For a few weeks Sparks was the talk of the Honolulu, as a wacky local news story that kept worming its way back to the front page. The story even made national news — “man ships self to tropical paradise.” It’s easy to see why, especially when he giving the press such good copy:

I’m from Indiana. I have a message from God. I am on my way to the Holy Lands to seek the true word of God. When I have been given the message, I will give it to the world.

Ultimately, everyone involved decided to throw up their hands and allow Sparks to stay in Honolulu with no charges filed or fines levied. He checked himself out of jail, wandered down to Pier 7 to pick up his carpenters’ tools, clothes, and toiletries, and started looking for work. He eventually found a job working at the shipyard in Pearl Harbor.

His box was returned to San Francisco so the bill of lading could be canceled. Sparks demanded a return of the $24.42 he’d paid in freight charges, but it was not forthcoming. The box had a brief run as a sideshow attraction, but eventually disappeared, a harbinger of things to come.

Dauntless

If you thought that was the end of our story, you’d be wrong.

If Ira C. Sparks couldn’t buy a ticket to the Holy Land, he’d sail there under his own power. In February 1923 he purchased a 26′ whaleboat from the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company, which he rechristened The Dauntless and anchored near Pier 3. He spent all of his free time turning The Dauntless into a sailboat. He gave it a fresh coat of pitch, rebuilt the deck, added masts and a rudder.

This time, he wasn’t alone. Christians who supported his mission sent him donations of money and food. An old sailor showed him how to rig up his sails and handle a boat. His co-workers from Pearl Harbor even pitched in. If by pitching in you mean “watching him from the shore and mocking him” with such pointed taunts as, “that boat will be your coffin,” and “you’re going to die out there.”

Sparks’ co-workers might have had a point. His naval experience had been limited to a few rowboat excursions on Lake Mississinewa. So he was bound to make mistakes. The first time he launched The Dauntless, it took on so much water it almost sank. Workers from a nearby foundry helped him put on a new galvanized iron bottom.

Meanwhile, the port authorities warned Sparks that if he wanted to sail to a foreign port he’d have to meet the same criteria as any other ship: file a manifest, prove he could navigate a boat, and get clearance to leave harbor.

In July Sparks accidentally pierced his hand on a spike while making some repairs. As he recovered, he took stock of the time and money he’d sunk into The Dauntless and decided he’d been a fool. So he scuttled and burned the ship.

And promptly started construction on The Dauntless II.

This time he went all out. The spruce dory was 22′ long, 7′ wide, with a mainsail and a jib and a comfortable cabin with a cot. It was loaded down with 80 gallons of fresh water, enough tinned food to last for 100 days, two bars of soap, a compass, maritime charts obtained from the US Weather Bureau, and a revolver.

Because the new Dauntless was under 5 tons, Sparks was able to circumvent federal regulations that would apply to larger vessels. He no longer needed to prove he could navigate, file a manifest with local authorities, or get official approval to leave the harbor.

The Dauntless was ready by the beginning of December, but Sparks was in no hurry to leave. First, he thought it would be disrespectful to sail before Christmas. And second, he had apparently been getting cold feet, so he wrote to his father back in Peru to get his blessing. Which apparently arrived as the new year dawned.

On January 9, 1924 — exactly a year and a day after his arrival in Honolulu — Ira C. Sparks and The Dauntless sailed out of Pearl Harbor shortly after noon. A crowd of 1,000 well-wishers came to see him off on his journey. He gave them a brief speech:

Goodbye, boys. I’m sorry to go. I like Honolulu. I have made many friends here, but I feel it is my duty to get to the Holy Land. Trouble not the Master for prayers for him who goes down to sea in The Dauntless; leave that to him and God.

Sparks hoisted a flag of his own design, white cloth trimmed with a golden braid, and set sail. The crew of the pilot boat leading him out of the harbor threw a lei to him. Sparks doffed his lauhala papale and waved it to the cheering crowd as he vanished from sight.

Professional sailors thought Sparks was crazy to sail west in the harsh winter weather, and doubted he would even reach Kauai. Others, like Governor Raymond C. Brown, admired his pluck and dedication and faith. (Though privately, even they thought the poor fool was likely sailing to his death.)

On January 10 The Dauntless was spotted 40 miles off of Barber’s Point by a US Navy seaplane searching for a drowning victim, which took a few photos. On January 14 it was spotted by a Japanese steamer some 250 miles southwest of Niihau.

Then… nothing. No sightings, just silence.

The newspapers wrote him off as dead.

At the end of April, there was unexpected good news. Word of Ira C. Sparks and The Dauntless arrived from the Philippines. After sailing 73 days on across open water, he’d made landfall on March 21 at Tandag on Mindanao.

It had not been a great trip. Sparks had been through storms and swells that tested his faith and skills. He’d fallen asleep at the tiller and been knocked into the drink by a shifting boom. He’d lost a good chunk of his provisions to rats. But he’d made it. He sent a message back to Honolulu for the faithful.

They call this boat my coffin but I am not afraid. The vision that came commanding me to make this pilgrimage contained assurance that I would meet no danger on the way. I have a message from God.

Sparks’ new plan was to sail the boat through the Philippines to Singapore, where he would finish his journey to the Holy Land on foot. He took on some fresh water, replenished his food stores, and set sail from Tandag on March 25.

Locals spotted The Dauntless at Matimus Point, between Parang and Budas, on April 17, sailing west.

Then… nothing. No sightings, just silence.

The newspapers wrote him off as dead.

This time, they were probably right.

On August 13, 1925, The Dauntless was spotted on the east coast of Zamboanga, near Gatusan Island. It looked like it had been pulled onto the shore for repairs and maintenance. Oil, paint cans, brushes and overalls were found on the boat. But there was no sign of Ira C. Sparks. A search of the jungle turned up a small hut nearby, but it clearly hadn’t been used for some time.

Ira C. Sparks had just… disappeared.

There was some hope that maybe he’d been picked up by a tramp steamer, or was taking shelter with natives further inland. But no word ever came from Ira C. Sparks. (Well, no reliable word. Quite a few messages were found in bottles or tied to the claws of mynah birds, claiming to be from a shipwrecked Sparks, but they were all clearly the work of pranksters.)

I wish this story had a happy ending. I wish I could give you the triumph of faith over adversity, of determination over incredible odds.

But I can’t.

Ira C. Sparks had simply vanished off the face of the Earth. He was declared legally dead in 1928.

Many theories were floated to explain what had happened. Some thought Sparks had given up on his God-given quest and fled into the jungle. Others thought he fell overboard, or committed suicide. The leading and extremely racist theory was that Sparks had been murdered by cannibal Moros so they could get a hold of his gun. (This seems unlikely since the gun was still in the Dauntless and later sent to the Miami County Museum in Peru.) Family members and the faithful held out hope that Sparks was still alive, but anyone who went searching for his trail could not uncover a single trace.

The Dauntless remained in its final resting place, and became a landmark for sailors. Old salts would point it out to young hands and declare, “That’s where Ira C. Sparks met his end.” The young hands, in response, would say, “Who?” The ship was still there in the late 1930s, but it seems to have disappeared during World War II.

To his credit, Ira C. Sparks followed the path of Moses faithfully. Because, if you remember, Moses is allowed to see the Promised Land, but not allowed to enter. (What, did you think I put all that stuff from Deuteronomy at the beginning for fun?)

This story was pulled largely from contemporary newspaper reports. I actually stumbled across it while researching a different story that didn’t pan out. Turns out it’s hard to not follow a thread that starts with “Ira C. Sparks of Peru shipwrecked up on Zamboanga while trying to sail a coffin to the Holy Land.” But what sounded at first like a fun little diversion suddenly took a dark turn, and that somehow appealed to me more. Because while I can cheer for triumph over adversity, I find that I’ve got more sympathy for a dream deferred that ends in ashes and sadness.

Wherever you may lie, oh Prophet of the Pacific, may you rest in peace.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

If you’re looking for other mysterious unsolved disappearances, check out the 1976 disappearance of Key West fire chief Bum Farto (“With Both Hands”); the 1874 abduction of four-year-old Charley Ross (Series 11’s “Your Heart’s Sorrow”); or the 1809 disappearance of British diplomat Benjamin Bathurst (“Gone Guy”).

Sources

- “Sea-going box proves a poor place to live.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 8 Jan 1923.

- “Carpenter Sparks, of packing box fame, may remain in city.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 10 Jan 1923.

- “Man who sent self by freight proves puzzle.” Arkansas Democrat, 11 Jan 1923.

- “City gets rich on Ira; $1 for each day here.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 12 Jan 1923.

- “City loses its star guest as Ira’s Released.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 13 Jan 1923.

- “Ira C. Sparks takes job at Pearl Harbor.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 3 Feb 1923.

- “‘Stateroom’ of Ira C. Sparks sent to coast.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 7 Feb 1923.

- “Sparks, packing-box stowaway, gets ready with ‘The Dauntless.'” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 14 Apr 1923.

- “Sparks to sail next week in his tiny ark.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 11 May 1923.

- “U.S. may stop Sparks’ trip across ocean.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 15 May 1923.

- “Sparks doesn’t need help, but thanks helpers.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 19 May 1923.

- “Sparks spends $400 preparing boat for trip to India.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1 Jun 1923.

- “Sparks is injured.” Honolulu Advertiser, 13 Jul 1923.

- “Stowaway builds small boat for voyage to India.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1 Aug 1923.

- “Sparks delayed in daring trip across Pacific.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 4 Oct 1923.

- “Sparks, camera in hand, wants to see Orient.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 21 Dec 1923.

- “Sparks sails in tiny boat for Holy Land.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 9 Jan 1924.

- “Seamen say Sparks is sailing in coffin to Holy Lands today.” Honolulu Advertiser, 9 Jan 1924.

- “Opinion sharply divided over whether Sparks is courageous or crazy.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 10 Jan 1924.

- “Sparks gone for 92 days, believed to have perished.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 10 Apr 1924.

- “Praying carpenter lands on island.” San Francisco Examiner, 15 Apr 1924.

- “Sparks reaches Philippines.” Honolulu Advertiser, 24 May 1924.

- “Sparks sails from Philippines with Singapore as a destination.” Honolulu Advertiser, 11 Jun 1924.

- “Sparks lost, belief, boat found alone.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 14 Aug 1924.

- “Sparks boat, oil cans, overalls found, but religious navigator may have been picked up by steamer.” Honolulu Advertiser, 15 Sep 1924.

- “Sparks alive, or victim of Moros?” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 4 Oct 1924.

- “Sparks marooned on isle, says mynah bird’s note.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 21 Apr 1925.

- “Remember Sparks? Brother John will set out to search for him.” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 25 Sept 1925.

- “Faith-guided craft preserved.” Honolulu Advertiser, 5 Oct 1926.

- “How Ira Sparks’s divine call led to a watery grave.” San Francisco Examiner, 20 Feb 1927.

- “Parents give up hope for their son at sea.” Muncie (IN) Star-Press, 14 Nov 1928.

- “Declare Ira Sparks dead after 4 years.” Culver (IN) Citizen, 28 Nov 1928.

Categories

- Biography

- Daring & Epic Journeys

- Eccentrics & Prophecies

- Intriguing & Unsolved Mysteries

- Least Popular

- People & Places

- Series 6

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: