Bound in Mystery and Shadow

thou shall not suffer a witch to live

It was November 29, 1928 — Thanksgiving Day — and Oscar Glatfelter was working.

That’s the life of a farmer. There are always chores to do: animals to feed, crops to harvest, firewood to chop, fences to mend. The farm doesn’t care that that it’s a holiday for everyone else. So you work. And face it, what else was Oscar going to do? He’d only be in the way in the kitchen, and it’s not like he could kick back and watch football. Philo T. Farnsworth had only invented television two months before, and the Detroit Lions wouldn’t exist for another two years.

Glatfelter had finished his chores by noon so he decided to pay a social call on his friend Nelson Rehmeyer. The old coot was probably fine, but it couldn’t hurt to drop by and check. On the remote fringes of York County, Pennsylvania, where your nearest neighbor could be miles away, it was just the neighborly thing to do. Even when the neighbor could be as unpleasant as Nelson Rehmeyer.

Sure, when it came to pitching in at harvest time there was no one better. Nelson Rehmeyer was 6′ tall, 200 lbs., broad-shouldered and still strong as an ox even at age sixty. But if you had to have a conversation with him? Good luck. Nelson was tight-lipped and sour. If he did deign to speak he’d probably try to convert you to socialism, which had caused multiple arguments with his neighbors over the years. Nelson’s politics had even destroyed his marriage. Oh, he and his wife Alice were still married, but they maintained separate houses about a mile apart and rarely visited. In fact, no one would have visited Nelson Rehmeyer at all if he weren’t such a damn good witch.

I should probably explain that.

Practical Magic

At the beginning of the last century, most of York County’s residents came from Pennsylvania Dutch stock. They’d kept a few things from the old country, including a belief in peasant folk magic — braucherei, in the old tongue, or “powwow” in English. Powwow isn’t really witchcraft in the modern sense. It’s more like a collection of folk medicine and superstition, spiced up with half-remembered bits and pieces from from alchemical, apocryphal and kabbalistic texts. It’s not organized or pagan. In fact, many of the ritual cures explicitly echo the structure of Christian prayers and call on God or Jesus for aid.

It’s surprising how widespread belief in powwow was at the time. Few people were probably all-in on the practice, but the rituals and recipes were so simple and easy they had a way of working themselves into every corner of your life. And if they were good enough for your meemaw, well, they’re probably good enough for you. It was estimated that half of York County’s population believed in witchcraft in some form or another. In downtown York there was a braucher on every corner promising miracle cures and selling talismans.

They practice of powwow was widely denounced by Christians who rejected it as Satanic, by doctors who saw it as ignorant quackery, and by modernists just plain embarrassed by the backwardness of it all. But the authorities generally wouldn’t bother the brauchers unless they were blatantly committing fraud.

Out in the country, brauchers and powwowers served their communities as witch doctors. They would typically learn the trade from a family member, but in a pinch they could also learn from a book. The most popular was John George Hohman’s The Long Lost Friend, which had a few major advantages over rivals like the Romanus-Büchlein. First, it was published in Harrisburg, so it was easy to get a copy. Second, it was written in English, which was handy if your German was rusty. Finally, while other grimoires were mostly about theory, The Long Lost Friend was practically a cookbook. Any given page might contain a prayer to ward off heart attacks, a recipe for a plaster to cure ulcers, or instructions for crafting a charm to protect you from wolves. Also, it promised you that no harm could come to you as long as you carried the book on your person, which was a bonus.

Anyway, Nelson Rehmeyer? He was one of the best powwowers out there. If you needed someone to cure the pox, spruce up your cherry trees with witchcraft, or make craft you a himmelsbrief (good luck charm), well, he was your man. Like most brauchers, he didn’t ask for payment for his services. That didn’t mean you weren’t supposed to pay a braucher, mind you. You might slip them a few dollars or a chicken or a helping hand around the farm after things had turned around.

Maybe that was what really brought Oscar Glatfelter out to Rehmeyer’s Hollow that Thanksgiving afternoon: not neighborly concern, but a nagging medical condition begging for a folk cure, or a lingering debt that needed to be repaid.

As he approached the Rehmeyer farm, Glatfelter heard the loud and insistent braying of a mule. He poked into the barn to see why it was kicking up a fuss, only to discover that the animal was starving. In fact, all the animals were starving, which meant Nelson hadn’t fed them for several days. That was worrying. Oscar rushed to the main house to make sure Nelson Rehmeyer was all right.

He was not all right.

Glaftfelter ran to his friend Dave Vanover, and then the two of them ran over to Spangler Hildenbrand’s place to use the phone. Someone had to call the police, after all.

Nelson Rehmeyer had been murdered.

Season of the Witch

York County’s finest rushed to Rehmeyer’s Hollow at once to take in the grisly sight.

Nelson Rehmeyer was in the kitchen by the stove. He had been hogtied and laid face down with his head resting on a block of kindling. His face was a bloody mess, almost unrecognizable. At some point his unknown assailants had covered him with a mattress and an old blanket and set them ablaze. The fire had sputtered out but it had done its damage. Most of the body was badly burned, in some places down to the bone. The medical examiner would later discover Nelson had two severe skull fractures and a collapsed lung.

Signs of a violent struggle were everywhere. The kitchen floor was covered with ashes and embers from the fire. A basin filled with bloody water sat next to the stove, with the stub of a cigar floating in it. An oil lamp was nearby, with its top screwed off. There was a discarded flashlight and a snap off of a halter on the floor. A kitchen chair had been smashed into pieces, and other furniture was clearly out of place.

The last time anyone could remember seeing Nelson Rehmeyer alive was on Tuesday, November 27, when he’d visited a cousin to borrow some buckwheat. The state of the farm suggested that he’d probably died that night — the chores had clearly been neglected for a day or two, but no longer than that.

At least the widow, Alice Rehmeyer, was able to provide a solid lead. On Monday night she’d been visited by two young men in the middle of the night. They wanted to know where Nelson was, but she’d had no idea. She suggested that if Nelson wasn’t out plowing the fields, maybe he was down at the Glatfelter farm plowing Emma Glatfelter. Then the visitors left.

Alice did’t think to ask for their names — she’d washed her hands of Nelson and powwow long ago, and had no desire to get sucked back into that mess. But she recognized one of the men as someone who used to live nearby, years ago. She gave the police a physical description: thin and gangly, with a long hooked nose and a prominent Adam’s apple. All she could say about the other fellow was that he was short.

Something about the almost ritualistic disposal of the corpse led the police to suspect that witchcraft might be involved. So they consulted Charles W. Dice, one of the more honest brauchers in the region, to see if he had any insights. Dice said the description of Alice Rehmeyer’s late night visitors rang a bell. The tall, gangly fellow was almost certainly John Blymire, itinerant laborer and part-time powwower. That meant the other fellow could only be Blymire’s constant shadow, John Curry.

So, who the heck were these guys?

The Sad Tale of John Blymire

In 1895 John Blymire was born into a long and illustrious family of farmers and brauchers. Great-grandfather Jacob was the seventh son of a seventh son, born at the exact moment a legendary witch had died, and a mighty magician. Grandfather Andrew and father Emmanuel were powerful powwowers, but had only a fraction of Jacob’s great powers.

Young John was obsessed with powwow, religiously poring over his copy of The Long Lost Friend and assisting his father and grandfather with rituals whenever he could. He also claimed to have visions and prophetic dreams. But he never quite had the touch of his illustrious forbears.

In the community John developed a reputation as the “creepy kid” and was ostracized. His teachers at school thought he might be slow-witted or feeble-minded. So no one really cared when he dropped out at age 13 to take a job at Bobrow’s Cigar Factory.

Sort of. John had a terrible work ethic and would only show up to work when he felt like it. And he was constantly ditching to go perform ritual cures for the unfortunate souls who needed the help of a braucher and couldn’t afford anyone better. Factory management only put up with his constant unplanned absences because he was such a hard worker. His nervous energy meant that he worked as hard as three less-motivated men men.

But in 1910, something changed. John had constant headaches and couldn’t sleep or eat. He lost weight and his skin hung loose. Sometimes he looked more like a scarecrow than a man. He became twitchy, paranoid, and depressed. Worst of all, his magic powers vanished overnight. He couldn’t try for even the simplest cure, and what few patients he had soon deserted him.

To the modern eye, it’s clear John Blymire was suffering from the triple whammy of severe malnutrition, the onset of puberty (delayed by severe malnutrition), and clinical depression.

John had an alternative explanation. He’d been hexed.

Obviously if magic can be used to help, it can also be used to harm. That’s the dark side of braucherei: hexerei, or black magic. Practitioners of the dark arts studied forbidden tomes like the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses to learn rituals that could summon demons, call down curses, and destroy their enemies.

And now one of these hexers was targeting John Blymire.

There were ways of lifting a hex, but first John had to find out who had placed it on him. Alas, John and the Blymires could not discover the true identity of his tormentor, no matter what divinations they performed.

Meanwhile, the curse ruined John’s life. He bounced from job to job and barely had enough money to scrape by. The lack of funds kept him bouncing from rooming house to rooming house, though he also kept moving in the hopes that this time the hex would not follow. Every spare cent, every free moment, was spent consulting other local brauchers to see if they had any leads, to no avail.

He starting turned to brauchers further away. He made a 160-mile round trip to Reading twice a week for six months to sit with the famous “Professor Gentzler.” The Professor tried to lift the curse with a series of custom-crafted charms and a few drops of dove’s blood administered orally. This treatment also failed, which the Professor attributed to John’s lack of faith. (John, for his part, started to suspect the Professor was a fraud. See? Lack of faith.)

Then, in 1917, the hex suddenly disappeared. The cause was obvious: John had fallen in love with Lilly Halloway, his landlord’s daughter, and his depression lifted. The two young lovers were soon married, and his new father-in-law helped John get a steady job at a lumber mill. He started sleeping and putting on weight, and his magic powers started to return. He even consulted a local doctor — a real doctor, not a witch doctor — who lent him some medical texts and tried to convince him that his “curse” was nothing more than depression.

Things started looking up for John Blymire.

Then John and Lilly’s first child died after only five weeks. Their second child was born prematurely and died after three days. John started to spiral, losing his job and all of his powwow.

The hex was back.

This time, John decided braucherei was not enough, and began consulting black magicians. He spent a small fortune on necromancy, voodoo, and kabbalah, once again to no avail.

In 1923 John started consulting with York’s most notorious magician, “Doctor” Andrew C. Lenhart. Lenhart was more con man than folk healer, a huckster who had mastered the art of stringing patients along with empty promises. His go-to move was suggesting that the source of a hex was someone “very close” to the victim, thereby driving a wedge between his patients and the loved ones trying to free them from Lenhart’s clutches. That move had gotten Lenhart into serious trouble on at least one occasion, when a patient murdered her sleeping husband. But he still used it.

And he used it on John Blymire.

John began acting cold and distant towards Lilly, and his father-in-law noticed. Knowing Blymire’s state of mind and Lenhart’s reputation, he started to fear for his daughter’s safety. The Halloways had John involuntarily committed to the state home for the insane in Harrisburg with a diagnosis of “psychoneurosis, neurasthenic type” with a severe case of “the witchcraft delusion.”

Forty-eight days later, John escaped the asylum by calmly walking out the front door during a baseball game between the inmates, and sticking out his thumb to hitch a ride. No attempt was made to recapture him, because the asylum was overcrowded and underfunded. After a year he was a free man.

Author Marian Gibson states that during this period, John tried to murder Lily, spent a month in prison, and after being released spent the next several years hiding out under the assumed name “John Albright.” I have been unable to find any confirmation of these claims.

John and Lilly divorced, and the Halloways warned him to stay far far away from their daughter. John returned to his series of odd jobs and his never-ending quest to find his tormentor.

The Sad Tale of John Curry

John Curry was six years old when his father died in 1920. His mother soon remarried one Alexander McClain, an ill-tempered drunk who doled out daily beatings to his stepson. Understandably, Curry preferred to stay away from home as much as humanly possible. Unfortunately, he also preferred to stay away from school as much as humanly possible. Curry’s perpetual truancy eventually got his stepfather dragged into court, and the beatings got worse.

In February 1927 John Curry walked into a recruiting office and enlisted in the U.S. Army. He was only 13 years old, but apparently looked very mature for his age. He was sent to Fort Meade for basic training and sent his first paycheck home to his mother. Mrs. McClain freaked out when she realized where her son had gone, and she called the Army in a panic. Soon after Curry was dishonorably discharged and on his way back to York.

He couldn’t go back to school, so he took a job working in the Bobrow Cigar Factory. He found himself mysteriously drawn to one of the other workers there, a skinny, twitchy fellow who the claimed to have magic powers. That was how John Curry met John Blymire.

Curry had lived in York proper for most of his life, and never been exposed to braucherei. It fascinated him. Maybe black magic and curses could explain why his life was so miserable. Soon, the 14-year-old Curry and the 33-year-old Blymire were inseparable. In effect Curry became Blymire’s apprentice, even though the braucher could barely manage even the simplest spell any more. But that never stopped him from trying.

The Sad Tale of Wilbert Hess

While working at the cigar factory, Blymire and Curry met a local truck driver, Milton Hess. In casual conversation it came up that Blymire was a braucher. That caught Hess’s attention, because he was cursed.

Milton Hess was not a truck driver by choice. He had once been a prosperous farmer, but in recent years his crops failed, his cattle wasted away, and his chickens were stolen. His wife Alice Ouida was listless and lethargic. Milton always felt like he was being boiled alive and could barely work or sleep. Ultimately, The Hesses had to sell off large parts of their farm and take jobs in town. Milton worked as a truck driver at the Pennsylvania Tool Manufacturing Company. His sons worked for a nearby lumber mill.

The explanation for their woes were obvious. The Hess family had been hexed. Unlike John Blymire, they knew exactly who was behind the curse: Milton’s sister-in-law, Ida.

At some point after Milton’s brother died he and Ida had a property dispute over the road that connected their two properties. Milton cut off Ida’s access to the road, and Ida retaliated by building a new road and cutting off Milton’s access to the old one. And then, presumably, by hiring a black magician to curse them.

The curse was effective. Milton’s finances were crippled, and could not afford to hire a real braucher to lift it. But he could afford to hire John Blymire.

John Blymire and John Curry made a visit to the Hess farm and confirmed that it was indeed cursed. Blymire offered to lift the hex for $40, but gladly accepted the meager $10 that the Hess family could scrape together on such short notice. The duo made some strange occult observations, gave Milton Hess a good-luck charm to neutralize any active hexes, and retired to Blymire’s boarding house to divine the true name of the magician who was bedeviling his new friends.

Blymire hadn’t forgotten his own hex, either. Over the summer he scraped together enough money to visit one of the most feared local brauchers, Nellie Noll, “The River Witch of Marietta.” It was money well spent, because Nellie Noll delivered results. Over six sessions she provided a slow dribble of ever-more specific information about Blymire’s tormentor.

- First, she confirmed that Blymire was indeed cursed.

- Second, she revealed the curse had been woven by a man.

- Third, an old man.

- Fourth, who lived in the country.

- Fifth, and who Blymire had known since childhood.

- Sixth, that it was Nelson Rehmeyer.

John Blymire did not believe her. The Rehmeyer and Blymire families had known each other for generations, and he knew the Rehmeyers did not practice hexerei. The two families traded magical services as a form of professional courtesy. As a child John had even picked up a few pennies digging potatoes on the old man’s farm.

There was no way Nelson Rehmeyer was the source of his curse.

Nellie Noll told John to take a dollar bill out of his pocket and put it on his left hand. Then she told him to flip it into his right palm portrait-side up John did as she instructed, then gasped in horror. There, where George Washington should have been, was the face of Nelson Rehmeyer staring back at him.

The River Witch was right. For years Nelson Rehmeyer had been pulling the wool over the world’s eyes, convincing everyone he was their true friend, while in reality he had been the blackest of black magicians.

But now that he had been exposed, the curse could be broken. First, Blymire needed to get Rehmeyer’s copy of The Long Lost Friend, or barring that, a lock of his hair. Whatever he managed to get, he needed to bury it in a deep hole behind the barn. Then, and only then, would John Blymire finally be free.

For the first time in years John Blymire could see an end to his torment. But then reality set in. How could he ever hope to get a hold of Rehmeyer’s spellbook or hair? John had been wasting away for two decades, both physically and spiritually, while Nelson was still as strong as an ox. It seemed impossible.

Then, in mid-November, John Blymire had a vision. It was all so obvious. Rehmeyer was not just the source of his problems. The old man must have also cursed John Curry and Milton Hess. Fate had brought them together. Individually they were powerless, but if they worked together, they could all be saved.

He explained his plan to the others. Curry was on board immediately. He was on board for anything. The Hess family was not so easily convinced, because they had never heard of Nelson Rehmeyer. Blymire told them the information came directly from the the River Witch of Marietta, and that was all it took. The Hesses were on board.

The Last Witch Hunter

For ten days John Blymire meditated, preparing himself for the mystic battle of wills to come.

On Sunday, November 25, he told the Hess family that the time was right and that they should all leave immediately to confront the sorcerer. The Hesses were all for it, but, well, their oldest son Clayton needed the car for work that night, and it was a long way to go in the dark. Maybe they could go tomorrow instead? Blymire sighed, and told them where to pick him up the following night.

On Monday, November 26 the Hess family car picked up Blymire and Curry shortly after dark. The group consisted of wife Alice Ouida, 22-year-old son Clayton and his wife Edna, and 18-year-old son Wilbert. As they made the long drive through the woods, Wilbert had an attack of nerves (or maybe indigestion) and was let out of the car so he could walk home and settle his stomach. Shortly thereafter, Clayton dropped Blymire and Curry off at the edge of Rehmeyer’s Hollow.

The two men trudged through the fields to the main house and pounded on the door, but no one was home. Then they walked over to Alice’s cottage to ask where her husband was, only to discover she had no idea — she hadn’t seen him for four days. Dispirited, they started to trudge back to the road, but suddenly noticed a light at the main house and rushed back. Nelson Rehmeyer heard them pounding on the door, and came down to let them in.

Blymire asked if Rehmeyer still had a copy of The Long-Lost Friend. Rehmeyer responded in the affirmative. So far so good — now all Blymire needed to do was break Rehmeyer’s will and get him to hand over the book. But then he lost control over the conversation. Every time he tried to mount a psychic assault, Nelson Rehmeyer would steer the conversation over to unrelated topics, like farming, or the weather, or socialism. He was either blissfully ignorant of why he’d been roused in the middle of the night, or deliberately screwing with his visitors.

Personally, I lean towards the latter explanation. Nelson Rehmeyer had been a braucher for years and knew that if late-night visitors weren’t there for a cure, then they were up to no good. His next move proves it.

Shortly after midnight Nelson Rehmeyer declared that he really needed to get some sleep, and told Blymire and Curry they could sleep on the couch. Nelson slept like a baby, knowing his would-be psychic assailants were too broken to attempt anything during the night. In the morning he cooked his two visitors breakfast and sent them on their way. It was a humiliating defeat.

As Blymire and Curry hitched their way back to York, the decided that if they couldn’t beat Rehmeyer psychically, they’d have to defeat him physically. When they reached town they made a beeline for Swartz’s Hardware Store to buy some rope that they could use to tie up their victim, and then made their way to the Hess farm, where they told the family that this time one of the Hesses would have to step up.

Blymire and Curry wanted young, strong Clayton to join them. Clayton respectfully declined. He couldn’t afford to miss a day of work, and besides, he had a wife and a two-year-old son. He’d gladly give them a ride, though.

All right, then, they would take Wilbert. Wilbert did not want to go either. He was a good boy, and all of this magic talk scared him. Then his mother broke into tears, moaning and wailing and wondering what would become of the family if this terrible curse could not be lifted. Wilbert fell for her “poor poor pitiful me” routine hook line and sinker, and agreed to go for the good of the family.

On Tuesday night the trio arrived at the Rehmeyer house at 9:30 PM. They pounded on the door, but there was no answer. Blymire started yelling loudly, which brought Rehmeyer to the window to ask them what the heck they were doing. Blymire claimed to have lost his copy of The Long Lost Friend on his previous visit, and asked if he could come inside to find it, or, barring that, borrow Nelson’s. The ruse worked, and Rehmeyer, still in his union suit, came downstairs to let them in.

Blymire and his young assistants pushed their way into the kitchen and demanded that Rehmeyer turn over his copy of The Long Lost Friend. Rehmeyer, realizing that something was up, glowered at them and then suddenly declared it was too cold. He threw on a sweater, grabbed some firewood from outside, and started lighting the stove while Blymire sputtered impotently.

Blymire repeatedly demanded Rehmeyer hand over the book, and old man calmly responded he had no idea what Blymire was nattering on about about. He suggested if Blymire had lost something, maybe it had dropped behind the couch last night when he was sleeping.

Blymire walked over to the couch and made a show of searching behind it — then suddenly jumped on Rehmeyer and forced him to the floor. Curry and Hess grabbed ropes and tried to tie down the old man’s limbs. Rehmeyer fought like a lion, but even he couldn’t ward off three men at once.

With herculean strength the old man struggled to his knees and asked his assailants what they really wanted. Blymire told him to shut up and started beating him over the head with the first thing he could find, a piece of firewood. Curry and Hess followed suit. When that didn’t knock the fight out of the old man, Blymire picked up a heavy kitchen chair and smashed it over his head. That did trick.

Rehmeyer told his attackers he’d let them have the book. They backed off, Rehmeyer fumbled in his coat… and then threw his wallet into Blymire’s chest. Blymire indignantly declared that he wasn’t there for Rehmeyer’s pocketbook, and the assault resumed.

Soon Curry and Hess were holding Rehmeyer down on the ground, and Blymire slipped a noose around his neck and began strangling him. As the old man drifted in and out of consciousness, Curry repeatedly beat him over the head with a piece of firewood while Blymire and Hess took turns kicking him in the stomach.

After an hour of merciless beating, Nelson Rehmeyer groaned and died. Blymire elatedly shouted, “Thank God! The witch is dead.”

Blymire, Curry and Hess ransacked the house looking for Rehmeyer’s copy of The Long Lost Friend, but could not find it. Eventually they realized it must be in the basement, where Rehmeyer did most of his powwowing, but they were too scared to go down the stairs even though the sorcerer was dead. They conducted a brief search to see if they could find the riches Rehmeyer was rumored to possess, but all they found was an old tin with $2.80 in it, which they split three ways.

In the end, Blymire declared that they didn’t need the book after all. Since Rehmeyer was dead, all of his hexes were now broken.

Now all they had to do was cover their tracks. Burning down the house seemed like the best option — it would look like an accident, and destroy all the evidence. Curry took the lead, pouring water over everything in the belief that would wash away any fingerprints. Then he threw a mattress and a blanket over the corpse, doused them with kerosene from a nearby oil lamp, and set everything ablaze. The three witch hunters fled outside to watch from a safe distance.

From behind the barn the trio fancied they could see Nelson Rehmeyer dancing in the flames. Then they realized the fire was dying down. They started towards the house to try and rekindle the flames, but were startled by a car coming down the road and ran. As they walked back to York in the dark, Blymire made his accomplices swear they would never tell another soul what had happened that night.

Shortly after 1:30 AM Wilbert Hess arrived at the family farm and immediately told everyone what had happened. They did not seem to be all that concerned. Clayton told his brother not to worry, just to read his Bible and pray, “and if the Lord sees fit he’ll take care of you.”

Back at his boarding house Blymire threw his bloody pants and jacket on to the fire before they could be discovered.

Curry’s parents barely even registered that he’d been gone.

On Wednesday, November 28 Blymire showed up at the Hess farm and told the family he wanted to return to Rehmeyer’s Hollow and finish burning the house down. The Hesses thought that was a terrible idea and refused to help. They told Blymire to relax, put it all behind him, and have a happy Thanksgiving.

He did. Dinner tasted like manna from heaven, and that night, he slept the sleep of the just for the first time in years.

The Crucible

Of course he didn’t know that the York police were already hot on his trail, thanks to a hot tip from fellow bottom-feeding braucher Charles W. Dice. (That would teach him for poaching Dice’s patients.)

But the police had a problem: they didn’t know Blymire from Adam. But they did know John Curry, who was one of York’s most notorious juvenile delinquents, and exactly where to find him: at his stepfather’s house at 136 East Princess Street.

The cops found Curry there just after midnight and brought him in for questioning. Between the police threatening him with prison and his stepfather threatening him with the beating of a lifetime, Curry cracked like an egg. He confessed to the murder and gave the authorities everything they asked for, including John Blymire’s current address.

An hour later detectives roused John Blymire from his bed in a Chestnut and Pine boarding house and dragged him down to the police station. At first the sleepy Blymire arrogantly denied everything, but when he was told Curry had confessed his attitude shifted. He admitted his involvement in the murder and also gave up Wilbert Hess, who hadn’t even been on their radar.

Hess was nabbed the following morning when he showed up for work at a lumber yard in Grantley.

When the story broke it went national. Why wouldn’t it? The day after Thanksgiving is usually a slow news day, and even if it wasn’t, this story it had it all. Terror on Thanksgiving! An unrepentant killer! Insular backwoods types! Witchcraft in modern America! Senseless depravity in a small town that was somehow both remote and yet easily reachable from every large city on the East Coast! The upcoming trial promised to be a media circus covered by every major news outlet.

Well. The good people of York were not going to have any of that.

The town fathers were not eager to have York portrayed as a superstitious backwater. They realized that the couldn’t stop the press from coming, but they did everything they could to make its job difficult. They severely restricted access to the courthouse and hired additional bailiffs to toss trespassers. They outlawed photography inside the courthouse and rejected applications to run telegraph and telephone lines into the building. And they scheduled the upcoming trials to take place in Courtroom #2, the smallest one in the building.

When the trials got underway in early January, they made an even bolder move. The judge and prosecutor declared that witchcraft had nothing to do with this trial. It was a simple case of felony murder, even if the “robbers” had only managed to steal $2.80.

It’s actually unclear what their motivations were for doing this. It may have been a conspiracy to try and make the trial less sensationalistic. The judge and prosecutor were both transplants and may have not realized how widespread belief in witchcraft was throughout York. They may have been trying to secure the death penalty or undercut a potential insanity defense. And they may have decided that the motive was irrelevant since every other aspect of the crime was clearly premeditated. Or all of the above.

The trials opened on January 7, 1929. Blymire and Curry were represented by indigent counsel. The extended Hess clan managed to scrape together enough money to hire the best criminal lawyer in the county, Harvey A. Gross, to represent Wilbert. Gross made a motion that the cases be tried separately, which was granted.

Blymire was up first.

The district attorney maintained that the sole motive for the murder was robbery, even though the Rehmeyer’s were dirt-poor and the “robbers” had only made off with $3.00. Though, uh, he completely forgot to introduce any evidence of this motive until he was prodded to do so by the judge.

Detective Ralph Keech testified that in their confessions Blymire and Curry claimed that robbery was the sole motivation for the murder. Which was strange, because those same confessions definitely mentioned witchcraft.

The defense argued that Blymire was insane. They tried to introduce evidence about witchcraft again and again, but each time they were shot down by the district attorney and judge.

Then, during cross-examination of Clayton Hess, the district attorney thoughtlessly asked what Blymire had told the Hess family when he first returned from the murder. Clayton answered honestly: Blymire said, “I got the witch.” The court erupted and the DA spluttered, only to be chided by the judge for walking right into that one.

Fortunately for the prosecution the judge decided to adjourn court early that day, and the next day Clayton’s testimony was so heavily restricted that that he was a useless witness for either side.

When the jury went to deliberate, the judge instructed them that belief in witchcraft and similar delusions did not constitute insanity or qualify the defendant for leniency. The verdict came quickly: guilty of murder in the first degree, with a sentence of life imprisonment.

The Curry trial was next. He was tried as an adult because of his advanced age of fourteen. His defense argued that a lifetime of abuse had rendered Curry incapable of distinguishing right from wrong. That didn’t fly, either, and he got the same as his friend: guilty of murder in the first degree, with a sentence of life imprisonment. When the foreman read the verdict Curry turned pale as a sheet, and his mother sobbed uncontrollably and fainted.

Hess’s private attorney actually managed to get some witchcraft introduced into the trial by coming at it obliquely rather than head-on. He deployed an unusual defense, making his client look like an unwilling participant, a mama’s boy who had been chosen by his family to take the fall for a heinous crime. It worked, to an extent. Hess was found guilty of second degree murder, with a sentence of ten to twenty years.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the murder the York County Medical Society decided to step up its campaign against powwow and other folk remedies. Stepping it up apparently meant “writing stern editorials” and “encouraging the police to do something about it” without, you know, actually doing anything meaningful or concrete.

They did manage to convince the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to send an undercover agent to investigate local brauchers suspected of fraud. His arrival was trumpeted in all the papers which sort of defeated the purposes. No prosecutions were forthcoming.

In 1934, John Curry’s life sentence was commuted to 20 years in view of his young age. He was paroled on June 29, 1939. During Curry’s stay in prison his cellmate, an art forger, had given him painting lessons, and Curry turned out to be a halfway decent artist. He was drafted into the Army in 1943 and worked as a cartographer in the European theater, helping to draft the maps used to plan D-Day. After the war he was awarded the Bronze Star and a scholarship to the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, but could not attend because it would have violated the terms of his parole. After mustering out he raised turkeys and became a local portrait painter of some renown. He died in 1963 of a heart attack.

Wilbert Hess was paroled on June 16, 1939. Ironically, though he’d been reluctant to participate and had received the lightest sentence, he served just as much time in jail as Curry. He became a respectable citizen, an electroplater at Teledyne McKay, and tried to put the murder behind him. He died in 1979.

John Blymire was thrown into Pennsylvania’s most secure prison, Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia. He was sentence was commuted on February 9, 1953 and he was paroled shortly after. He worked off-and-on as a janitor and security guard, and died in 1972.

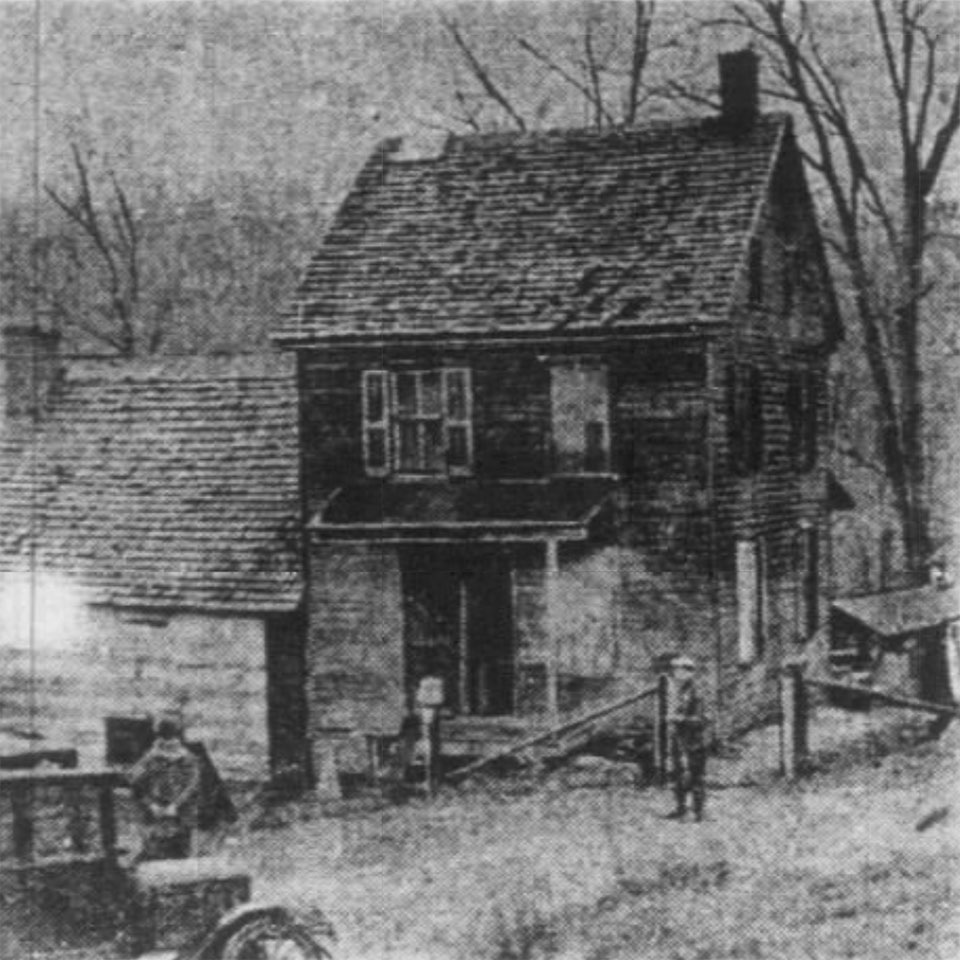

Over the years the Rehmeyer house fell into disrepair, but in 2007 his great-grandson decided to restore it to its original 1928 appearance. It re-opened as a tourist attraction in 2013 and as far as I can tell is still open today. [Update: As of 2023, the house is no longer open to the public.]

Belief in powwow still hasn’t completely died out, though there are far fewer open practitioners today. Don’t get me wrong, though. Magical thinking is alive and well as ever. It’s just that when the residents of York go looking for a cure they’re less likely to reach for himmelsbriefs and dove’s blood and more likely to turn to more proven methods. Like crystals and reflexology.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

Other famous residents of Philadelphia’s legendary Eastern State Penitentiary include Paul Jawarski, the murderous leader of Pittsburgh’s Flathead Gang (“The Terror of Gillikin Country”); child kidnapper William Westervelt (“Your Heart’s Sorrow”); and Joseph Peters of the Blue-Eyed Six (“Make Insurance Double Sure”).

The murder of Susan Mummey, the so-called “Witch of Ringtown Valley” (“Seven Years In Hell”) happened only six years later and sixty miles away.

Sources

- Free, Shane. Hex Hollow. 2015.

- Gibson, Marion. Witchcraft: A History in Thirteen Trials. Scribner, 2023.

- Guile’s, Rosemary Ellen. The Encyclopedia of Witches & Witchcraft (Second Edition). New York: Checkmark, 1999.

- Hohman, John. The Long-Lost Friend. Reading, PA: self-published, 1820.

- Lewis, Arthur. Hex. New York: Trident, 1969.

- Nesbitt, Mark and Wilson, Patty A. The Big Book of Pennsylvania Ghost Stories. Mechanicsburg (PA): Stackpole Books, 2008.

- “Youth, 14, admits York County murder.” Carlisle (PA) Sentinel, 29 Nov 1928.

- “Murder farmer to get lock of hair to break spell, three confess.” York Dispatch, 30 Nov 1928.

- “Slayer in witchcraft crime is suspected of killing Gertrude Rudy.” York Dispatch, 1 Dec 1928.

- “Witch murder case counsel is named by court.” York Dispatch, 3 Dec 1928.

- “Another link to Rudy murder chain which is tightening on Blymyer.” York Dispatch, 4 Dec 1928.

- “Blame trio for murders.” York Dispatch, 14 Dec 1928.

- “Pow-wow secrets revealed.” Pittsburgh Courier, 15 Dec 1928.

- “No pyrotechnics at murder trials.” York Daily Record, 1 Jan 1929.

- “Insanity defense in Blymyer trial, attorney decides.” York Daily Record, 9 Jan 1929.

- “Life term for Blymyer; Curry now faces jury.” York Dispatch, 10 Jan 1929.

- “Find Curry boy guilty of first degree murder.” York Dispatch, 11 Jan 1929.

- “Murder in second degree verdict passed upon Hess.” York Daily Record, 14 Jan 1929.

- “Court denies Blymyer and Curry new trials in ‘hex’ murder case.” York Dispatch, 23 May 1929.

- “‘Hex’ slayer is free to start life anew.” York Dispatch, 19 Jun 1939.

- “Second hex kill freed from prison.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 Jul 1939.

- “Blymire released from penitentiary.” York Dispatch, 7 Feb 1953.

- “John Blymire dies at 76, principal in ‘hex’ slaying.” York Daily Record, 12 May 1972.

- “Obituaries: Wilbert G. Hess.” York Daily Record, 17 Jan 1979.

- McClure, Jim. “Murder and witchcraft: the incredible story of York County’s Hex Murder.” York Daily Record, 14 Oct 2017.

Links

- Diener, Emeline L.K. “Fines and Portents.” Pennsylvania Lawyer, Vol. 42, No. 6 (November/December 2020).

- Hex Hollow documentary

- The Long Lost Friend

- The Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: