Cloud Dongs

George Grey Barnard's Pennsylvania Capitol sculpture groups

In August 2023, my cousin Tim and his fiancee Bonnie were getting married in Lancaster.

As #7 and I made our travel plans, we realized that even though she has spent a large chunk of her adult life in Pennsylvania she had never visited many of its most famous historic sites. We decided to make a meal of it and spent the week before the wedding road tripping around the Commonwealth. We visited Valley Forge and Gettysburg. We visited Steamtown in Scranton. We marveled at the natural beauty of Jim Thorpe. We got chocolate kisses and spa treatments in Hershey. We saw classical art, classic cars, and the world’s largest coffee pot. We stopped at every Wawa, Sheetz, Rutter’s, or Nittany MinitMart we could. We had a Turkey Hill Experience.

At one point in the middle of all this we found ourselves in Harrisburg with a few hours to kill. It was a gorgeous summer day, so I decided to walk the grounds of the capitol building. I parked the car on Walnut Street and began strolling, taking in all the luscious greenery and various war memorials and monuments and resisting the urge to key my state senator’s car.

And that is how I found myself on the capitol steps, staring up at the main entrance, looking befuddled and thinking, “Huh, what’s up with that?”

This is the story of what’s up with that.

A Palace of the Arts

Pennsylvania’s first capitol building was built in Philadelphia in 1729. It was a grand old structure but had to be left behind when the Commonwealth government moved to Lancaster in 1799. The building was sold to the City of Philadelphia and is still around today. You may know it better as Independence Hall; you know, the place where the Declaration of Independence and Constitution were written and where Holling Vincoeur and KITT had a rap battle about slavery.

For the next several decades Pennsylvania did not have a permanent capitol building. Even when the government permanently relocated to Harrisburg in 1810 the legislature did not have a forever home until 1822, when a grand federal-style building was erected for them.

Alas, on February 2, 1897 stray embers from the fireplaces landed on wooden structural supports and the capitol burned down in the middle of a blizzard. The legislature immediately authorized the construction of a new capitol building with only two major requirements: the building had to be fire-proof, and the entire cost of the project should not exceed $550,000.

A quick architectural competition was won by Chicago’s Henry Ives Cobb. Talented as Cobb was, there wasn’t much he could do with a budget like that. His original sketches envisioned a grand marble-clad Neoclassical structure along the lines of the US Capitol, which wound up being scaled back to an ugly rectangular brick office building.

To many the new capitol was an embarrassment. It was the height of the Gilded Age and Pennsylvania was one of the wealthiest, most populous, and most industrialized states in the nation. Why should its legislature be forced to meet in building that critics compared unfavorably to a factory or barn? Should not the greatest state have the most beautiful and triumphant civic building?

In 1901 the legislature was shamed into holding another competition to “finish” Cobb’s capitol, with three requirements: the new building had to incorporate Cobb’s old building into its structure; the total budget should not exceed $4,000,000; and the architect had to be Pennsylvanian.

The second competition was won by Philadelphia’s Joseph Miller Huston. He was a relative unknown, only 36 years old and only recently struck out on his own, but his ambitious vision knocked the legislature’s socks off.

Huston conceived of the new capitol as a palace of the arts, glorifying not only the history of Pennsylvania but the history of all western civilization, uniting sculpture and painting to create “literature in stone.” His design drew on a recent trip to Europe for inspiration, incorporating the towering dome of St. Peter’s, the bronze doors of Florence’s Baptistery, and the grand stairs of the Paris Opera.

That grandiosity extended to the decorations as well. Huston planned to pay top dollar for murals, reliefs, fixtures, and sculptures. He lined up a murderer’s row of Pennsylvanian artists to create them: Austin Abbey, John White Alexander, Violet Oakley, William B. van Ingen…. and George Grey Barnard.

George Grey Barnard

Odds are you are not familiar with George Grey Barnard, but back at the fin de siècle he was a big deal. Even two decades later Charles H. Caffin’s American Masters of Sculpture ranked him among the greatest American sculptors, second only to Augustus St. Gaudens.

Barnard’s connection to Pennsylvania was tenuous at best, but tenuous was good enough. He had been born on May 24, 1863 in Bellefonte, but his father was an itinerant preacher who kept moving the family further and further west.

As a teenager in Muscatine, Iowa Barnard apprenticed himself to a jeweler to learn the art of engraving, and quickly surpassed his master. Engraving would have been a very solid career, but during a trip to the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition he fell in love with the art of sculpture. He turned out to be very, very good at it. As Barnard devoted himself to his new craft he claimed he could feel “the great hand of God at his back” pushing him toward ever-greater success.

In 1880 Barnard moved to Chicago, Illinois where he engraved watches during the day and studied under sculptor Leonard Volk at night. Eventually he managed to save up $75, which became his tuition for the newly-formed Art Institute of Chicago. In 1882 he used the profits from two early commissions to travel to Paris and entered a competition to win a seat in the École nationale des Beaux-Arts. Which he handily won.

Barnard spent the next few years studying under academic sculptor Pierre Jules Cavelier and developing his mature style, which sought to marry the Neoclassical formalism of Academic sculpture with the muscular power of a young Michaelangelo and the expressive sensuality of a Rodin. Not that Barnard, Academic to the core, would ever admit to being influenced by the latter. Even when Rodin was the one handing him awards, like the jury prize he won in the 1894 Salon du Champ de Mars.

It wasn’t long before Barnard found his first major patron: Alfred Corning Clark, whose family had been early investors in the Singer Sewing Machine Company. Clark first commissioned Barnard to create a grave marker for his “special friend” Lorentz Severin Skougaard and was quite pleased with the result, which depicts two muscular men in a sort of vigorous dance who reach towards each other but are kept apart by a big block of marble. (Read into that what you will.) Other works he completed under Clark’s patronage include two naked wrestlers entitled “The Struggle of the Two Natures in Man” (now in the Met) and the reclining and aggressively nude figure of “The Great God Pan” (now on the campus of Columbia University).

Encouraged by Clark, in 1895 Barnard moved back to America and set up shop in New York City. Then Clark went up and died in 1896. Other American collectors were put off by the sculptor’s smug superiority and his career floundered. Eventually he moved back to France, where they still loved him. He received a gold medal at the Paris exhibition of 1900, and received a remarkable write-up from critic M. Thibault Sissons:

We have a newcomer, George Grey Barnard, who possesses all the qualities of a great master. He belongs to that young and virile America where efforts are manifested in various unexpected forms. He demonstrates with singular power his contempt for conventional methods, and his passionate longing for the new and creative art manifests itself in everything he puts his hand to. To him all nature is new and he has great breadth of conception.

The Apotheosis of Labor

As a famous American artist at the peak of his powers, Barnard was the idea person to head up the sculptural program for the capitol project. Joseph Miller Huston offered him the job in July 1902 and Barnard rose to the occasion. He pitched the idea that the building’s facade would a single unified artwork depicting “The Apotheosis of Labor.” Here’s how he described his intentions:

I saw that the idea of Greeks was to make gods. They created beautiful forms, beautiful symbols which they set on pedestals, but in their statuary they stopped short, deliberately, at anything that was individual or characteristic of humanity. The day of the gods is passed. This is the day of the people and it is the people that I want to fix in sculpture.

The capitol’s main entrance would be flanked by four groups of caryatid columns, representing waves of immigration to Pennsylvania from the earliest Native Americans right up to the Pennsylvania Dutch. Those carytids would support a monumental bronze frieze showing the march of history from barbarity to civilization. At ground level the building would be ringed by marble sculptures picking out allegorical moments from Pennsylvania history that supported the grand theme.

It was an ambitious plan that involved 42 groups of statuary, which would have to be executed in under four years to be ready for the capitol’s dedication in June 1906. It wouldn’t be cheap, either. Huston and the capitol planning commission had set aside $300,000 for sculpture, and Barnard estimated the bronze frieze alone would cost nearly $165,000.

He was able to save the Commonwealth some money by arguing that no American craftsman could complete the work as quickly or cheaply as the French or Italians, and the capitol commission begrudgingly agreed. The artist returned to his studio in Muret-sur-Loing, outside Fontainbleu, and got to work.

Well, almost. Once the artist was out of sight the legislature looked at the skyrocketing cost of the capitol project and began having second thoughts. In October they began going over the plans and questioning every line item. In December they slashed the budget considerably.

Barnard’s contract was cut back from $300,000 to $100,000.

Once again he rose to the occasion, finding a way to condense the symbolism of his original plan into two smaller statuary groups that would flank the capitol’s main entrance. Even this reduced scope involved completing thirty individual figures in heroic scale.

He completed the first 1/4 scale models in May 1903 and then progressively scaled them up and reworked them: first to 3/4 scale, then to life size, and eventually to a truly heroic 5/4 scale. (The contract called for 7′ tall figures, but Barnard figured 9 1/2′ tall figures would look better next to the gigantic building.)

It was not easy work, and Barnard had numerous setbacks. At one point his studio flooded, which caused $68,000 in damages, destroyed his plaster models, and delayed the work for months. To rebuild he was forced to borrow against his life insurance, sell off much of his private art collection, and start a side business scouring the countryside for medieval sculptural and architectural fragments which he resold to American collectors and museums.

The real problems started when he asked the Commonwealth for funds to help rebuild… and was denied. The artist was to be treated like any other contractor and would only receive the remainder of the balance due when work was completed.

Barnard, who was used to working for patrons who were patient, understanding and who could always be squeezed for a few more bucks, had no idea how to cope with a budget-conscious legislature. He did not take the rejection well.

He stopped work on his models, and even threatened to destroy them when the Commonwealth suggested it might seize them. He complained that he had done fifteen times more work than the contract had called for, and the Commonwealth responded that no one had asked him to do that. He groused that he hadn’t been paid in nearly eight months; and the Commonwealth responded that he received every dollar he was entitled to despite missing every deadline specified in the contract’s strict timetable. He moaned that he had only taken the job at a reduced rate because he had been promised additional contracts worth nearly a million dollars, to which the Commonwealth responded that it had no idea what heck he was going on about.

It was clear there was a significant gap between what Barnard had been promised by Huston and what was actually in his contract. The artist felt he was morally entitled to the former, and the legislature was not going to give him one penny more than was legally called for by the latter. With so much daylight between their positions, negotiations between the two parties quickly broke down.

When the capitol was dedicated by President Theodore Roosevelt on October 4, 1906 there sculptures were conspicuously absent. Even without them, Teddy called the new capitol “the handsomest building I ever saw.”

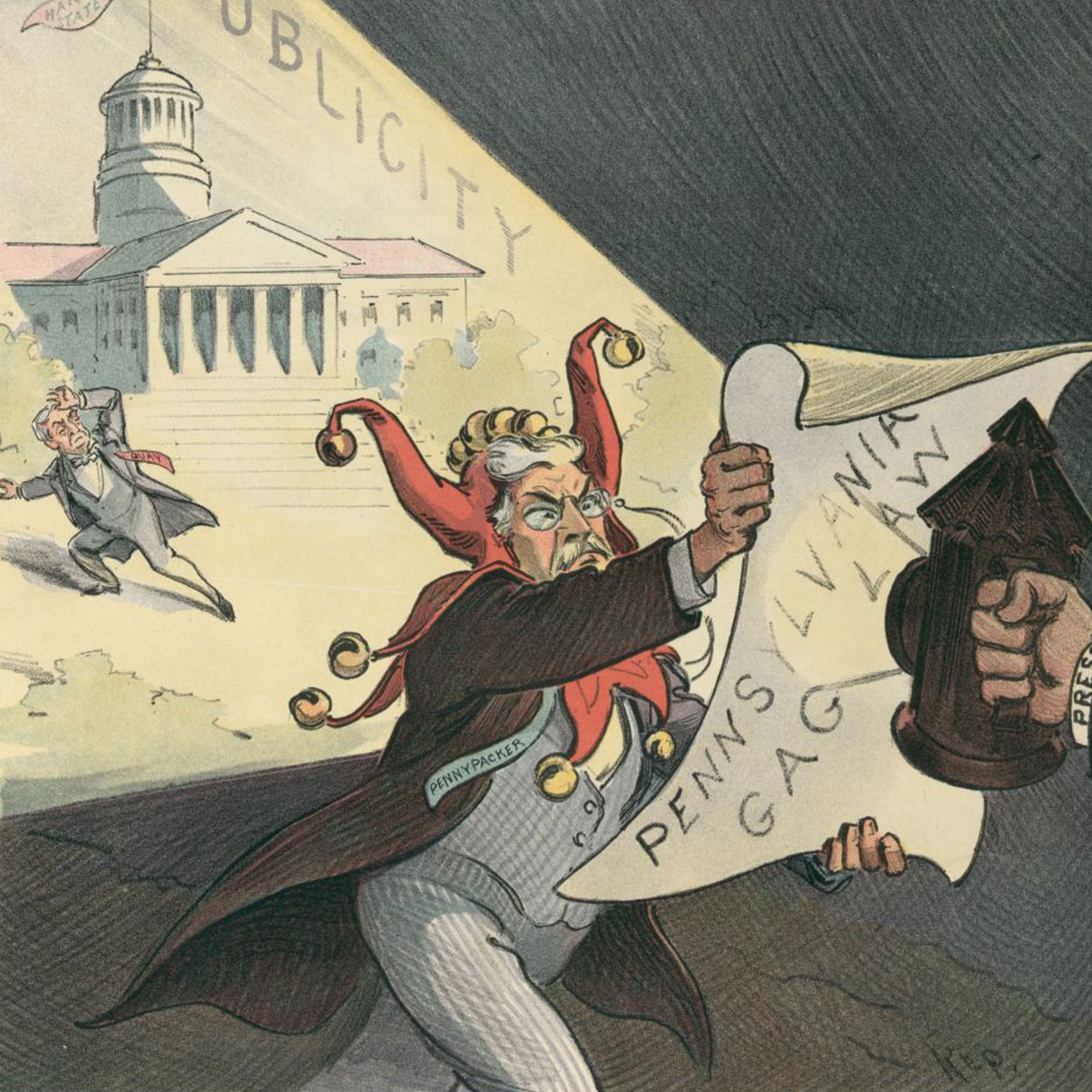

The Desecration and Profanation of the Pennsylvania Capitol

Now, you may be wondering why capitol architect Joseph Miller Huston did not rush to Barnard’s defense. Turns out Huston had problems of his own.

For instance, there was a bit of a stir in June 1906 when the capitol’s monumental bronze doors were installed and it was discovered that the decorative panels, which were supposed to contain portraits of historical Pennsylvanians like William Penn and Benjamin Franklin, also included portraits of then-governor Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker and several of his cronies, as well as the capitol’s general contractor, the owner of the company that cast the doors… and Joseph Miller Huston himself, right on the doorknobs.

That was the least of Huston’s problems, though. You see, as the project wound down, the capitol planning commission had to submit its final report. The initial budget of $4,000,000 turned out to have been wildly optimistic; the actual cost wound up being well over $13,000,000. The legislature and the public were shocked.

It did not help that Governor Samuel Pennypacker had been swept out of office, along with most of the old Republican machine of the late Senator Matthew Quay. Incoming governor Edward Sydney Stuart had campaigned as “The Governor Who Cares” who would fight corruption and graft. He ordered Treasurer William H. Berry to audit the project.

Berry quickly discovered that Huston had set up a novel procurement scheme where what vendors got paid was not based on the actual value of goods but on their total weight or square footage. Some of that overcharge was then kicked back to Huston.

The worst offender was Philadelphia wholesaler John H. Sanderson, who was paid millions of dollars for furniture that could be had much more cheaply. For example, there was a shoe-shine stand whose fixtures had a retail value of $124. Sanderson had estimated its area at 88 square feet, and was reimbursed at a rate of $18.40 per square foot for a total of $1,619.20. That’s a 1200% markup.

Huston, Sanderson, and several others were charged with graft and corruption in 1910. Sanderson avoided a criminal conviction through the clever legal gambit of “dying before the trial.” The others were not nearly so lucky and were convicted of defrauding the Commonwealth. Huston was sentenced to two years in Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary — and served every minute of the sentence.

I’m getting ahead of the story, though. Just remember that this is all going on in the background while Barnard is grousing about not being paid.

In early 1907 the Treasury’s audit showed that Barnard had already received $87,000 of the $100,000 promised by his contract. The artist had quickly burned through that cash, expecting that the legislature would just keep throwing money at him, but by law the remainder of the contract could only be paid on receipt of the final product.

Right now Barnard only had plaster models. And $13,000 would not begin to cover the cost of turning the models into finished marble statues, or getting them shipped from Europe to America.

The Commonwealth could not decide whether Barnard was part of Huston’s kickback scheme or just bad at business. Comments from former governor William Alexis Stone, the president of the capitol commission, seem to indicate he favored the latter explanation.

I haven’t any idea what he is talking about. Barnard is an artistic lunatic — that’s all I can say about him. He is liable to say anything. He has completely failed in the undertaking he contracted to perform, and he has put us to no end of annoyance and expense. He has placed a lien on the statues he has completed for money that he imagines is still due him, in spite of the fact that he has already been paid the full amount of the money that we agreed to give him for the completion of the work. It is hard to tell what the outcome will be. We have made no new offers to him of any kind.

On the other side, ex-Governor Pennypacker decried the capitol commission as crass materialists with no appreciation of the arts, and defended both Huston and Barnard.

What we needed in his position was not a bookkeeper or the cashier of a bank, but an artist and a poet, with imagination enough to design, with enthusiasm enough to carry his inspirations into execution, and with none too keen an appreciation of the importance of mere money.

Mind you, Pennypacker wasn’t exactly a disinterested third party here. He wasn’t directly implicated in the kickback scheme, but his administration had failed to exercise any sort of oversight over the capitol project. (Pennypacker was also a bloviating, self-important boob who did not like any of his decisions being questioned, but that’s true of most politicians.)

In the end cooler heads prevailed and a compromise was worked out. The Commonwealth and several of Barnard’s friends from New York engineered a buy-out of the completion bond the artist had posted at the beginning of the project. That freed up an additional $20,000 to get things moving again.

New York’s famous Piccirilli Brothers began finishing the statues in November 1908… and then stopped work when Barnard ran out of money. (Put another notch in the “he was a terrible businessman” column.) His friends passed the hat once more and hoped that this time the $100,000 they raised would finally be enough.

Thankfully it was.

What’s Up With That

The sculptures were finally finished in April 1910, and the following month they were exhibited in Paris at the Salon du Champs de Mars.

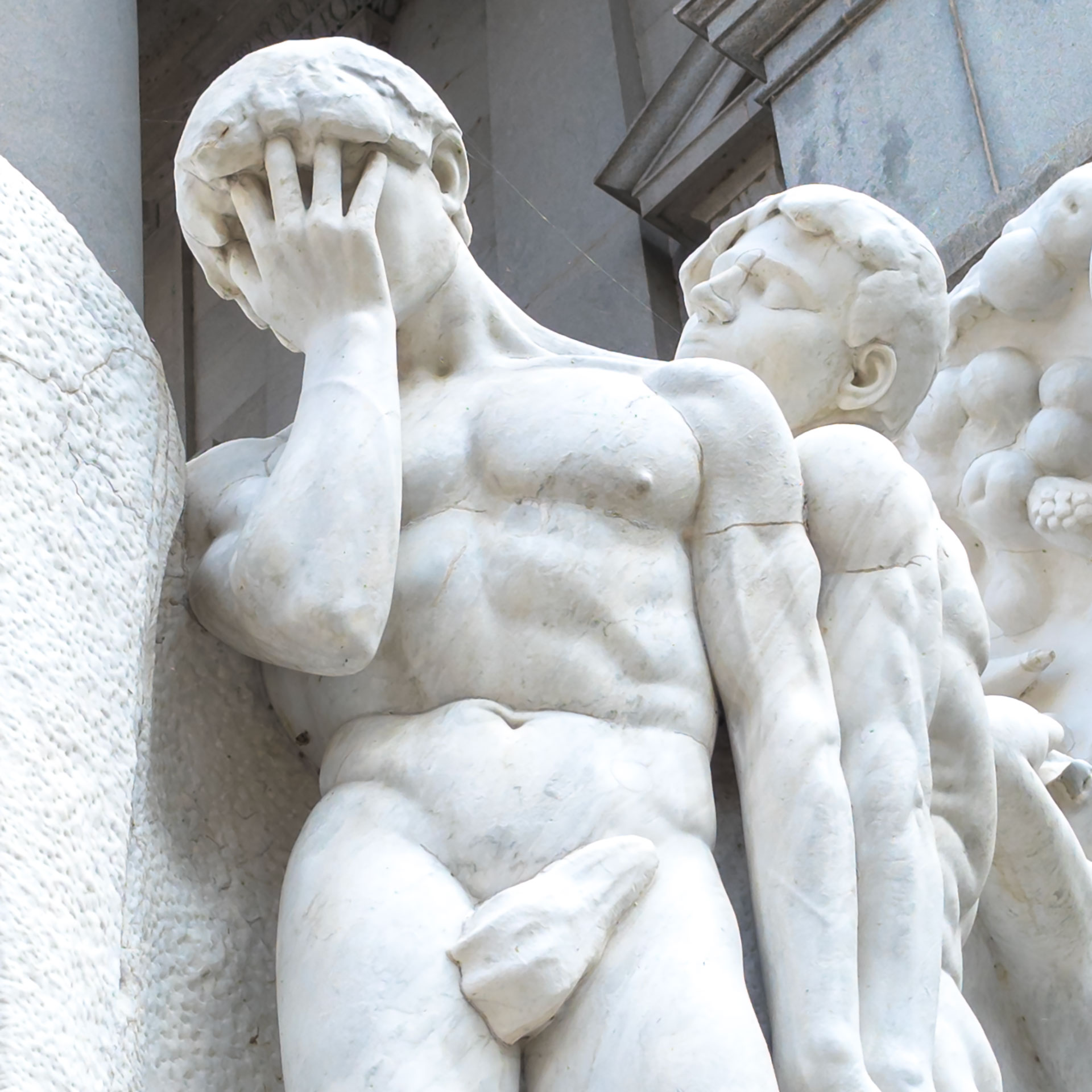

As they are intended to be seen, the group of figures on your right is The Burden of Life: The Broken Law. It is intended to depict the consequences of failing to obey the law, whether secular or divine. In the very back you have a high relief of Adam and Eve cavorting in the chaotic but plentiful Garden of Eden. They seem happy but their children are not included in that tableau and are all clearly being punished for their parents’ original sin. “The Forsaken Mother” tosses her head back in unexpectedly sexy anguish. “The Mourning Woman” casts her sad eyes down at the “The Kneeling Youth” who pleads for mercy from an indifferent “Angel of Consolation.” “The Burden Bearer” is crushed under a heavy load. “Two Brothers,” presumably Cain and Abel, trudge forward joylessly. At the very end of the pedestal you have the homoerotic figures of “Despair and Hope” who clasp hands and gaze longingly and desperately at the other group of figures across the way.

The group of figures on your left is Love and Labor: The Unbroken Law. At the back you have an unnamed farmer and his wife, a new Adam and Eve, also surrounded by plenty but by a more ordered plenty. Their children enjoy peace, happiness, and prosperity and are represented by the “Prodigal Son”, “The Thinkers,” “The Philosopher-Teacher”, “The Baptism”, “The Young Parents”, and “Two Brothers” who presumably don’t want to kill each other. At the front of the pedestal you have the “The New Youth,” a young couple who turn their gaze out across the Susquehanna River towards the frontier and the promise of the future.

Barnard tried to deflect a strictly Biblical reading of the work, which would have been mildly inappropriate for a government building. Instead he claimed the idea that following the law leads to joy and breaking it leads to suffering was just “peculiarly appropriate to the headquarters of a legislature.” I don’t know if he was entirely successful, because the work has Biblical allegory written all over it.

Do I like them? Not really. Like a lot of Academic sculpture the work is competently done but not particularly compelling. It doesn’t help that the supposedly “happy and prosperous” figures don’t seem all that happy. The figures are stiff and awkwardly posed. The symbolism is also obscure. It’s easy enough to grasp that one of the two groups is doing poorly and the other is doing well, but it’s not clear why without that Biblical allegory to fall back on.

Barnard’s decision to render the figures at extra-heroic scale may have been a mistake. It does make them stand out against the enormous capitol building, but increasing the size of the figures without increasing the size of the base means they’re packed in tight. That means everything starts to blend together into an undistinguished morass, an amorphous slab of bright marble. Smaller figures would have more room to breathe and be lively.

The sculptures would also benefit from being on smaller pedestals. Up close everything has to be taken in at an extreme angle, making really hard to make out what’s going on. Everything looks a lot better from a distance. And from the side. I’m not saying they need to be on the ground like “The Burghers of Calais”, but maybe on a 3’ or 4’ pedestal.

Or maybe that’s all just me.

Anyway, the Salon’s jury of sculpture loved them, with one judge praising Barnard as the greatest sculptor since Phidias. The sculptures were given a place of honor, flanking the main entrance to the Grand Palais.

Photographs from the Salon soon reached the United States, where they caused a bit of a stir. You see, Barnard’s figures were mostly nudes and the American public was still mostly prudes.

A vocal minority began attacking the artist and his work. The loudest voice belonged to the Ancient Order of Hibernians, which at this point was basically a Catholic decency league. They claimed public nudity would have a “demoralizing effect on the youth of the Commonwealth” and opposed installing the sculpture on the capitol grounds.

Barnard was not surprised in the least. He had battled American prudishness before. Most notably, Alfred Corning Clark had intended to donate “The Great God Pan” to Central Park, but New York had said “no thanks” due the statue’s rather sensuous pose. Which is to say, reclining on its side, thrusting its rather prominent genitals right into your face at about head height. (It ultimately wound up on the Columbia campus.)

There has been some criticism, because these 30 figures I have executed are nude. Only in the nude could I have given adequate expression to these figures. Drapery would have spoiled the effect. Only through delineation of the nude human form can great emotions be shown. You cannot drape a symbolic figure in an overcoat and expect it to be anything but a marble dummy.

It is curious that this criticism should come from men, while women approve of the work as is. Women have better artistic sense than men. They are inspired by the human form, but men are not similarly inspired. They think the nude suggestive. I understand that the Pennsylvania state authorities are going to drape them. I shall make no protest, but I am sorry.

Others fought back on his behalf. The usually staid Harrisburg Telegraph said censoring the statues would make Pennsylvania a laughingstock. The Fine Arts Journal struck back at what they saw as Pennsylvanian provinciality…

It is amusing or disgusting, as you please, to learn that the inhabitants of Pennsylvania are so modest that they cannot endure the nudity in the magnificent sculptured groups which George Grey Barnard is placing on the capitol at Harrisburg… Should these statues be draped it would be one of the greatest insults that the world has been called upon to endure for many centuries.

While Barnard clearly thought the demands to censor his work were absurd, there was no fight left in him and he just wanted to get the whole ordeal over and done with. He announced he would cover the naughty bits, though he would not resort to anything as cliché as a fig leaf. No, he announced he would throw a “blur of marble” over the naughty bits to create a “misty effect” that would be barely noticeable.

The statues arrived in the United States in December 1910. They were moved to the capital and set up on their pedestals, but hidden from view by tents until they could be censored and then formally unveiled.

It was widely reported on May 14, 1911 that a crowd of female art lovers of tore down the tents to take in Barnard’s work in, uh, its full glory. Except… it turns out that might not be true. The only reports I’ve been able to find are either in the Chicago Tribune, or cite the Tribune as a source. The incident would have definitely made the headlines if it had actually happened, because it was Mother’s Day. And President Taft was visiting Harrisburg. And because the work of covering everything up had started on May 11.

Anyway, this is what caught my eye that day. This is because while Barnard promised “little blurs of marble” that is not what he delivered. Instead, we have big lumps of plaster, starting in the crotchular region but held in place by an extension that goes up and along the hip crease. This is no subtle misty effect, but a misshapen cloud that’s right in your face, a gigantic eye-catching penis sheath.

If anything, Barnard’s cloud dongs are more noticeable and distracting than an actual penis. One has to wonder if that was, in fact, the whole point. My personal theory is that Barnard was thumbing his nose at the censors through malicious compliance. Alas, there’s no way to know for sure.

(I also couldn’t help but notice that not all of the penises are covered up, either. I’m not sure whether little boy penises are still okay, or whether the plaster clouds have crumbled away over time and no one’s bothered to replace them. If you work for the capitol, write in and let us know!)

Barnard Day

Barnard’s statues were officially unveiled on October 5, 1911.

It was five years too late, but better late than never.

The Commonwealth turned the unveiling into a huge party. The legislature declared October 5 to be “Barnard Day.” Over 800 special guests were invited to the dedication ceremonies, including city and state officials, distinguished artists, and other prominent citizens of Pennsylvania. (Joseph Miller Huston could not make it, because he was in jail.) They were joined by a crowd of several thousand spectators.

A chorus of 400 elementary school students sang the national anthem. Barnard’s father, a Methodist preacher, read the invocation. Miss Mabel Cronise Jones read an ode to the statues. A brass band played a “Barnard March” that had been composed for the occasion. Numerous dignitaries rose to make speeches praising the work. Most notably, Attorney General John C. Beall declared:

The frieze of the Parthenon, perfect in classic line and form, made Athens famous as the art center of the world; and so Barnard’s statues will make our Capitol and its citadel, like the acropolis, a Mecca of art.

Well, I don’t know about that. It’s still pretty impressive, though.

The Pennsylvania capitol sculpture groups may have represented the pinnacle of Barnard’s career. His only subsequent major work is a sculpture of Abraham Lincoln for Lytle Park in Cincinnati. It’s really quite powerful, depicting a young Lincoln as a man of the people. So naturally everyone hated it, especially Robert Todd Lincoln, because they wanted an idealized heroic Lincoln. In the middle of the century critics began to reevaluate Barnard’s work and his stock fell dramatically. Today he’s been virtually forgotten.

He did make a huge mark on the art world, though. The medieval odds and ends he sold as a side hustle formed the core of collections in major museums across the country. His personal collection was purchased by John D. Rockefeller Jr. and became the core of the Cloisters in New York.

Barnard passed away on April 24, 1938 and asked to be buried near his greatest accomplishments. He was interred in Harrisburg Cemetery, just down the street from the capitol… on the opposite side of the building from his sculptures.

(To be fair, to bury Barnard somewhere with a good view of the sculptures he would have to be interred on the capitol grounds or in the Susquehanna River. Can’t win them all, George!)

Connections

You can add Joseph Miller Huston to the list of former residents of Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary. That list also includes insurance fraudster Joseph Peters of the Blue-Eyed Six (“Make Insurance Double Sure”); kidnapper and possible child-murderer William Westervelt (“Your Heart’s Sorrow”); John Blymire, the York County hex murderer (“Bound in Mystery and Shadow”); and Paul Jawarski of the bank-robbing Flathead Gang (“The Terror of Gillikin Country”).

His plan for the capitol wasn’t great, but Henry Ives Cobb was a very distinguished and successful architect. One of his triumphs was the Fisheries Building for the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and Columbian Exposition, which he built in a grand Richardsonian Romanesque style. We, of course, have visited the 1893 World’s Fair several times, in the company of such notables as Diamond Jim Brady (“He Could Eat It All”), John Alexander Dowie (“Marching to Shibboleth”), and Cyrus Reed Teed (“We Live Inside”) and discussed it directly with Initiate #1893, Michael Finney (“The White City”).

Sources

- Brown, Milton W. The Story of the Armory Show. Joseph A. Hirshhorn Foundation, 1963.

- Caffin, Charles H. American Masters of Sculpture. Musson Book Company, 1922.

- Cummings, Hubertus. “Pennsylvania’s State Houses and Capitols.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Volume 20, Number 4 (October 1953).

- Dedication Ceremonies of the Barnard Statues, State Capitol Building, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Oct 4, 1911. Legislative Commission of the State of Pennsylvania, 1912.

- George Grey Barnard: Centenary Exhibition, 1863-1963. Pennsylvania State University, 1964.

- Goley, Mary Anne. “John White Alexander’s Industrial Lunettes for the Pennsylvania State Capitol: The Unfinished Story.” IA: The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archaeology, Volume 34, Number 1/2 (2008).

- Gruber, Samuel D. “The Brunner Plan for the Harrisburg Capitol Complex.” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies, Volume 87, Number 1 (Winter 2020).

- Pennypacker, Samuel W. The Desecration and Profanation of the Pennsylvania Capitol. William W. Campbell, 1911.

- Seitz, Ruth Hoover and Seitz, Blake. Pennsylvania’s Capitol. RB Books, 1995.

- Steffensen, Ingrid. “Toward an Iconography of a State Capitol: The Art and Architecture of the Pennsylvania State Capitol in Harrisburg.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 126, Number 2 (April 2002).

- Williams, Dan. “George Grey Barnard.” The North American Review, Volume 243, Number 2 (Summer 1937).

- “Alfred Corning Clark.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Corning_Clark Accessed 9/1/2024.

- “Barnard to Finish Work.” American Art News, Volume 7, Number 10 (December 19, 1908).

- “Editorial Comment.” Fine Arts Journal, Volume 24, Number 2 (February 1911).

- “Pennsylvania State Capitol sculpture groups.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pennsylvania_State_Capitol_sculpture_groups Accessed 10/3/2023.

- “Gotham’s art gossip.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 Nov 1895.

- “The fine arts.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 2 Jul 1899.

- “New Capitol commission met this afternoon.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 9 Jul 1902.

- “Bids for the new Capitol.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 10 Jul 1902.

- “Pennsylvania’s new Capitol to be a model building.” Philadelphia Times, 20 Jul 1902.

- “Artistically Capitol will be important.” Pittsburgh Post, 20 Jul 1902.

- “Contracts for painting and sculpture let.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 23 Jul 1902.

- “George Gray Barnard, Pennsylvania-born sculpture, will beautify new Capitol.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 23 Jul 1902.

- “Price of Capitol scaled down.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 1 Oct 1902.

- “Barnard will design statues for Capitol.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 13 Dec 1902.

- “Capitol ready Jan. 1.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 1 Jul 1905.

- “Fox visits Bernard.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 4 Sep 1905.

- “Can pay artists all right.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 22 Dec 1905.

- “Capitol Hill echoes.” Harrisburg Daily Independent, 2 May 1906.

- “Heads won’t be removed from bronze doors.” Harrisburg Daily Independent, 15 Aug 1906.

- “Pennsylvania’s missing marbles.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 24 Sep 1906.

- “Pennsylvania’s new capitol.” Daily Local News, 27 Sep 1906.

- “Berry finds overcharge in the new capitol job.” Harrisburg Daily Independent, 28 Sep 1906.

- “Legislative inquiry.” Intelligencer Journal, 29 Sep 1906.

- “Price of capitol is not excessive says J.M. Huston.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 29 Sep 1906.

- “Magnificent new Capitol is dedicated today with impressive ceremonies.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 4 Oct 1906.

- “Carson is not satisfied.” Pittsburgh Post, 17 Dec 1906.

- “Find Huston got $663 more than was his.” Pittsburgh Press, 12 Mar 1907.

- “Late news in brief.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 22 Apr 1907.

- “‘Big Fellows’ won’t be heard this week.” Pittsburgh Post, 23 Apr 1907.

- “Capitol statuary is not completed.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 May 1907.

- “Barnard is wrathy and won’t take more money.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 12 May 1907.

- “Tragedy of an artist’s life: George Gray Barnard and the Pennsylvania Capitol.” Pittsburgh Post, 26 May 1907.

- “Barnard yesterday returned to America.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 24 Jun 1907.

- “Barnard says he does not expect to make profit.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 25 Jun 1907.

- “Sculptor Barnard sees commission.” Reading Times, 26 Jun 1907.

- “Architect Huston, so George G. Barnard says, proposed plan to bleed Commonwealth of nearly three quarters of a million more, third being for Capitol sculptor.” Pittsburgh Post, 27 Jun 1907

- “Barnard is happy.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 28 Jun 1907.

- “Promises broken, sculptor Barnard gives up his work.” Pittsburgh Post, 8 Oct 1907.

- “My enable artist to complete work.” Pittsburgh Post, 20 Sep 1908.

- “Capitol statues coming next year.” Allentown Leader, 28 Aug 1909.

- “Barnard’s Capitol groups sensation of art world.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 28 Mar 1910.

- “Result of Barnard’s Genius photographed for first time.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 30 May 1910.

- “A.O.H. protest nude statues in Capitol.” Allentown Leader, 20 Aug 1910.

- “Will drape nude statues to please Hibernians.” Carbondale Daily News, 20 Sep 1910.

- “Capitol statues have been shipped.” Times-Tribune, 20 Oct 1910.

- “Dip into own pockets to assist sculptor.” Pittsburgh Post, 26 Nov 1910.

- “State Capitol statuary soon to be placed.” Pittsburgh Post, 1 Dec 1910.

- “Groups to be erected at once.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 21 Dec 1910.

- “Statues cause talk.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 30 Dec 1910.

- “Statues to be clothed.” Pittsburgh Post, 5 Jan 1911.

- “To drape or not to drape Barnard’s beautiful Capitol statuary is question that is agitating people and art students alike.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 7 Jan 1911.

- “Barnard doesn’t care.” Latrobe Bulletin, 12 Jan 1911.

- “No drapery says former governor William A. Stone.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 13 Jan 1911.

- “Women vote for undraped statues.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 19 Jan 1911.

- “Statues are still draped.” Wilkes-Barre Times Leader, 24 Jan 1911.

- “Oppose draping of Barnard group.” Pittsburgh Post, 14 Feb 1911.

- “Barnard reiterates promise he made to Star-Independent.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 4 Apr 1911.

- “Barnard has more to say on Capitol statuary draping.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 25 Apr 1911.

- “Sculptor Barnard does not worry.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 29 Apr 1911.

- “Barnard tells about his groups.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 11 May 1911.

- “Likely to pay Barnard.” Harrisburg Star-Independent, 17 May 1911.

- “George Gray Barnard would make Harrisburg Paris of Pennsylvania.” Harrisburg Telegraph, 20 Jun 1911.

- “$80,000 more will not cover Barnard’s debts.” Daily News, 7 Jul 1911.

- “Barnard statues are dedicated.” Pittsburgh Post, 5 Oct 1911.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: