Crepuscule in Blood and Guts

the most curious incident in the life of James McNeill Whistler

It was 1866 and James McNeill Whistler was going to war.

It was a moment when many of the adventurers the war had made of many Southerners were knocking about London hunting for something to do and, I hardly knew how, but the something resolved itself into an expedition to go and help the Chilians, and, I cannot say why, the Peruvians too. Anyhow, there were South Americans to be helped against the Spaniards. Some of these people came to me as a West Point man and asked me to join — and it was all done in an afternoon. I was off at once in a steamer from Southampton to Panama. We crossed the Isthmus, and it was all very awful — earthquakes and things — and I vowed, once I got home, that nothing would ever bring me back again.

I found myself in Valparaíso and in Santiago, and I called on the President, or whoever the person then in authority was. Then came the bombardment. There was the beautiful bay with curving shores, the town of Valparaíso on one side, on the other, the long line of hills. And there, just at the entrance of the bay, was the Spanish fleet, and in between the English fleet, and the French fleet, and the American fleet, and the Russian fleet, and all the other fleets. And when the morning came, with great circles and sweeps, they sailed out into the open sea, until the Spanish fleet alone remained. It drew up right in front of the town, and bang went a shell, and the bombardment began.

The Chilians didn’t pretend to defend themselves. The people all got out of the way, and I and the officials rode to the opposite hills, where we could look on. The Spaniards conducted the performance in the most gentlemanly fashion; they just set fire to a few of the houses, and once, with some sense of fun, sent a shell whizzing over towards our hills. And then I knew what a panic was. I and the officials turned and rode as hard as we could, anyhow, anywhere. The riding was splendid, and I, as a West Point man, was head of the procession. By noon, the performance was over. The Spanish fleet sailed again into position, the other fleets sailed in, sailors landed to help put out the fires, and I and the officials rode back into Valparaíso. All the little girls of the town had turned out, waiting for us, and as we rode in called us ‘Cowards!’

The Henriquetta, the ship fitted up in London, did not appear till long after, and then we breakfasted, and that was the end of it.

James McNeill Whistler as quoted in The Life of James McNeill Whistler by Elizabeth and Joseph Pennell

That’s the version of the story Whistler told his official biographers, Elizabeth and Joseph Pennell. He told other friends he had actually seen combat, that he had seized command of a Chilean gunboat and received a “baptism of fire amid a rain of shot and shell.” Others were told that a wound received during the revolution was the source of Whistler’s infamous “white lock” — a prematurely gray patch of hair in the center of his scalp.

It’s a fun story. The problem is it’s not true.

Here’s what really happened.

It Was A Moment

It was 1866 and James McNeill Whistler was in a pickle. A whole jar of them, to be honest.

A few years earlier Whistler had switched from etching to painting. Now, his etchings were good, but his paintings were a revelation: painterly and Impressionistic, precociously pretty, concerned more with composition than content. They received endless praise from critics, but did not appeal to the stodgy art collectors of England. Most of his sales were to friends and family, leaving him on a shaky financial foundation.

Whistler made a few attempts to broaden his appeal by incorporating faddish elements of pre-Raphaelism, neo-Classicism, and Orientalism into his work. The only thing he succeeded in doing was confusing himself aesthetically, and he had to spend several years straightening himself out.

Then there was Whistler’s mother — not Arrangement in Gray in Black No. 1 but the actual Anna McNeill Whistler. Anna had been caring for her terminally ill daughter-in-law Ida, but when Ida passed in 1863 Anna decided to move in with her oldest son in London. That was fine with Whistler, who was a bit of a momma’s boy, even though money was tight.

Of course, when Whistler took in his mother he also had to put out his mistress Jo Hiffernan, or at least set her up in another flat. It wasn’t great for his wallet, or his love life, or his relationship with his mother, who did not get along with Jo at all.

Whistler’s domestic situation was further complicated by the arrival of his younger brother William. Willie Whistler was yet another mouth to feed, but money wasn’t the problem. Or rather, it wasn’t the only problem.

You see, at the start of the Civil War, James self-identified as a Southerner. James was a life-long expatriate who had spent most of his childhood in Europe. His only connection to the South was through his mother, whose family left North Carolina for New York when she was just a girl. There was no need for him to pick a side, but pick a side he did. James began carrying himself like a Southern gentleman, dignified and genteel. Also racist, hypocritical, self-righteous, obsessed with personal honor, and prone to violent outbursts when he didn’t get his way. It was a bit over the top… but also shallow and skin deep. For all his Southern pride James wasn’t about to pick up a rifle and fight for the twin causes of slavery and white supremacy.

Willie, though, he was the real deal. He lived in Virginia, he married a sweet Georgia peach (the aforementioned Ida), and served as a field surgeon for the Confederate Army. Just by being around, he made James feel like a poseur — probably because he was.

In Willie’s defense, he didn’t mean to show up his brother. He didn’t want to be in London, but he didn’t have much of a choice. Four years of fighting had made him tired and fragile. The Confederate Army had given him an extended furlough, ostensibly so he could rest and relax in his mother’s care, but also so he could deliver secret messages to Confederate agents in Liverpool. By the time he arrived in April 1865, the war was over. Willie was a heartbroken widower, scarred by war, stranded in a foreign country with no home to return to and no means of support.

He wasn’t alone, either.

London was full of Confederate expatriates trying to figure out what to do next. Some emigrated to Central and South America to forge new lives there. Some settled permanently in Great Britain, while others bummed around the Continent waiting for the United States to declare a general amnesty.

Many of these ex-Confederates were in dire financial straits. Alas, they had only one marketable skill — fighting — so they became soldiers of fortune, looking for a new cause to fight for.

Spain gave them one.

South Americans To Be Helped

Spain was not having a great century. First Napoleon conquered them in six short weeks. Then they lost most of their colonies in less than a decade. By mid-century the country had rebounded a bit, but was still looking for ways to get its mojo back.

In 1862 the Spanish Navy sent a scientific expedition to South America — one that consisted of four top-of-the-line warships commanded by Admiral Luis Hernández-Pinzón Álvarez. It was an open secret that the expedition’s real purpose was to intimidate former colonies into rejoining the empire.

It didn’t work.

The expedition received a tepid reception in Uruguay and Argentina. All of the diplomatic niceties were observed, state dinners and dances and whatnot, but it was made very clear to the Spanish that their former colonies had no intention of returning to the fold.

They got much the same reception in Chile. When the subtle hints that they weren’t welcome weren’t picked up, Chilean diplomates bluntly told their visitors that “their absence was far more desired than their presence.”

The reception they received in Peru was downright frosty. The Peruvians had good reason to be hostile: Spain had never officially recognized Peruvian independence, and Spanish filibusteros had attempted to take over on numerous occasions. Even so, the Peruvian government did their best to be polite to their unwanted visitors.

The Peruvian people were less tactful. The presence of the expedition triggered anti-colonial riots in the northern district of Talambo. Several Spanish nationals incurred losses during the riots and bent the ear of Admiral Pinzón, who passed their demands for reparations along to the Peruvian government, which curtly responded that this was an internal affair and that the Spanish should butt out.

The Spanish responded by sending diplomat Eusebio de Salazar y Mazarredo to Chile. It’s unclear whether this was an attempt to escalate or deescalate the conflict. Salazar’s official title was “royal commisary,” a type of colonial administrator, which implied that the Spanish still considered Peru to be a colony. The angry Peruvians understandably refused to deal with the commissary at all.

In April 1864 Salazar unilaterally decided that Spain would get its reparations the hard way. He ordered Admiral Pinzón to blockade Peruvian ports and seize the nearby Chincha Islands in Pisco Bay. They were uninhabited rocks — but they were also covered with thousands of years of bird poop and a key part of Peru’s increasingly guano-based economy. In the previous year the nitrogen harvested from the islands was responsible for 60% of Peru’s gross domestic product.

Peru objected, and it soon became clear that Salazar had acted without prior authorization, or possibly as part of a secret conspiracy to provoke a war. Admiral Pinzón tried to smooth things over by returning a Peruvian warship he had seized; alas, during the handover he failed to raise or salute the Peruvian flag which was construed as a deliberate insult.

The Peruvians had right on their side, but the Spanish blockade crippled their ability to fight back. President Juan Antonio Pezet Rodriguez Piedra caved in February 1865 and agreed to pay reparations for the Talambo incident and reimburse the Spanish for the expense of occupying the Chincha Islands.

Of course, once the terms of the treaty were revealed to the Peruvian public, a popular uprising overthrew the Pezet government and the Chincha Islands War was back on. The conflict also spread to include the neighboring nations of Ecuador, Bolivia, and Chile.

Chile was drawn into the conflict in September 1865 when they refused to sell coal to the Spaniards, on the grounds that international law forbade neutral nations from selling war materiel to belligerents. The Spanish interpreted this as an act of war and responded with a naval blockade of Valparaíso and other major ports.

This was a dramatic and largely futile gesture. Chile famously has the longest coastline in the world, and there’s no way to effectively patrol it with a mere handful of ships. It also led to official protests from Chile’s trading partners like the United States, Great Britain, France, Russia, and Sweden. None of these nations would actually take the dramatic step of allying themselves with Chile, though. There was just no upside to it. But they did send fleets to “observe.”

Chile was screwed, because it didn’t have a navy. They quickly tried to acquire one, signing a deal with arms merchants in New York to provide ironclad ships to sink the Spanish fleet. That deal fell apart when the United States stepped in, ironically on the grounds that international law forbade neutral nations from selling war materiel to belligerents.

Adventurers the War Had Made

Well, if America was going to be Chile’s enemy, maybe the enemy of their enemy would be a friend. They made their way to London to seek out the aforementioned ex-Confederate mercenaries.

The man who answered their call was Henry Harrison Doty. Doty was not a military man. He was a merchant and inventor from Norfolk, VA. In 1863 he left Norfolk and settled in France, where he somehow landed a contract to build spar torpedoes for the Second Empire.

A spar torpedo is… okay, let’s be honest, it’s a big bomb on 10′ pole. The basic idea is that you use the pole to ram the bomb to into a ship below the waterline, set it off, and hope the resulting hole sinks the vessel.

Doty claimed to have come up with the idea on his own, which was lie. Spar torpedoes were first proposed by Robert Fulton as far back as 1810, and deployed with mixed results during the War of 1812. The problem was that you had to be right next to your target to attach the torpedo. It was hard to close that distance without getting spotted, and actually managed to plant one there was a good chance you would be caught in the blast.

Eventually advances in shipbuilding allowed for the construction of semi-submersible steam-powered vessels which rode so low in the water that only their smokestacks broke the surface. During the Civil War Matthew Fontaine Maury, the father of the Confederate Navy, commissioned several of these “torpedo rams.” E.C. Singer, nephew of the sewing machine magnate, upgraded the torpedoes themselves, improving the firing mechanism so they would only trigger after you had retreated to a safe distance.

One of these rams, the CSS Squib, was used by Maury’s assistant, Lieutenant Hunter Davidson to sabotage the USS Minnesota as it blockaded the James River. Despite this successful proof-of-concept the torpedo rams were never deployed because the Confederates had trouble building them.

It’s not clear how Doty became involved in the manufacture and sale of spar torpedoes and torpedo rams, but he did. Not many countries were buying, mind you, because spar torpedoes were controversial, the land mines of their day. The large naval powers hated them, mostly because they were effective. Cheap to make and easy to deploy, they were a great equalizer that allowed perennial underdogs to take down large, heavily armored, and extremely expensive warships. The United States and Great Britain led the campaign to ban the torpedoes on “humanitarian grounds.”

That was a problem for Doty, who traveled to London in 1865 to only to discover the Admiralty was not interested in his wares. He was just about ready to head back to France when the Chileans came a-knocking.

They soon struck a deal — Doty would provide three rams and enough torpedoes to blow the Spanish flotilla to Kingdom Come and back again, and when the deed was done, the Chileans would make him a captain in their navy and shower him with 300,000 pesos (about £60,000 in 1866 money, or about $11.2 million in today money).

Doty immediately went to work. He purchased an iron-hulled steamer, the Henrietta, and crewed it with every ex-Confederate he could find, including Hunter Davidson, the only man in the world with practical experience using torpedo rams in battle.

According to James McNeill Whistler, he was recruited by Doty because of his background as a “West Point man.” That seems unlikely. Few people remembered that Whistler had been a cadet, and those who did also remembered that he had flunked out despite receiving more than his fair share of second chances from the school’s commandant, Robert E. Lee. The most likely explanation is that Doty really wanted William McNeill Whistler, who would have been an excellent choice to serve as ship’s doctor, and Willie forced him to take Jamie as part of a package deal.

As for what was in it for Whistler… Well, maybe he thought the change of scenery would break up his routine and inspire him. Maybe he was fleeing the country because of his friendship with Irish nationalist John O’Leary, who had just been convicted of high treason. Maybe his relationship with Jo had hit a rough patch. Maybe he was trying to man up so he wouldn’t feel inadequate standing next to his baby brother. Maybe all of these things.

It was probably money, though. For serving as Doty’s secretary, Whistler would be paid £30/month, with an 8s per diem for living expenses. His travel expenses to and from Chile would be completely taken care of, and he was promised a share of the reward after the successful completion of the mission. That would enable Whistler to pay off all of his debts and live comfortably or years.

He couldn’t sign on the dotted line quick enough.

I Found Myself in Valparaíso

Doty and Davidson left Southampton aboard the Henrietta on February 1, 1866. Their plan was to reach France, take on a load of rams and torpedoes, and steam around Cape Horn to reach Valparaíso.

Whistler left Southampton aboard the RMS Solent on February 2. Since he was not hauling contraband war materiel he was able to take commercial vessels and cut across the Isthmus of Panama. That would allow him to reach reach Valparaíso before the Henrietta, so he could coordinate with the Chilean government in advance of Doty’s arrival. The artist was also escorting Doty’s wife, Astive Froidure Doty, who had not been allowed to sail with her husband because it was “improper” for a lady to be on a warship.

Neither ship sailed with Willie Whistler. The US Consulate would only issue passports to former rebels if they formally renounced he Confederate cause, which Willie was not prepared to do. That meant the mercenaries would have to make do with one Whistler — the one they didn’t actually want.

Whistler reached Valparaíso on March 12 after a “nerve-wracking” journey. The blockade was now in its six month, the country’s economy was collapsing, and everyone was tense and nervous. At least there was no shooting going on; there was a ceasefire while the two governments held peace talks.

The artist took up lodgings above a cafe and went to business. He met with Chilean officials, did a little spying around town, and took copious notes about everything he heard and saw. Really, though, there wasn’t much he could do until the Henrietta arrived. So set up his easel and began doing some sketching and painting.

At some point the Spanish learned about the spar torpedoes. That threw them into a panic, and they resolved to strike before the Chileans could strike back. On March 27 they called off the ceasefire and announced that in four days they would bombard the city with the objective of destroying “every palace, house, or hut within reach of guns.”

Foreign observers objected, but could not intervene without official sanction from their respective governments. On March 30 they all meekly hoisted sail and left the harbor for a safe position about three miles from shore. The residents of Valparaíso did much the same, retreating from the city center to the outlying hills. Whistler was among them.

The first shot boomed out at 9:00 AM on March 31. The Chileans pointedly did not return fire, but it wasn’t out of cowardice. They wanted to make it absolutely clear that the Spanish were the aggressors.

The bombardment was methodical and thorough. First the Spanish targeted Valparaíso’s merchant marine fleet, then the city’s defensive fortifications, then the harbor facilities, and then the warehouses along the wharf. They also fired a few wild shots into nearby houses and the surrounding hills.

By noon the Spanish had reduced the city to a pile of rubble and decided to call it a good day’s work. The foreign observers were allowed to sail back into port and help fight the fires that threatened the few buildings still standing.

The Spanish had made a crucial mistake. After the bombardment they were no longer welcome in any South American harbor. As they ran low on supplies they made a futile attempt to take what they needed by assaulting the Peruvian port of Callao, before finally giving up and retreating to the Philippines where they could refuel.

That was that, though it would take another twenty years for a peace treaty to be signed.

Then We Breakfasted

With the war over there was nothing left for Whistler to do but sit back, paint, and wait for the Henrietta to arrive.

It would be a very long wait.

Everything that could have possibly gone wrong had gone wrong. Shortly after leaving France the Henrietta ran into fierce storms off Madeira and had to turn back to Lisbon and then Cherbourg for repairs. While those were being made the crew started getting mutinous, so Doty and Davidson fired them all and had to re-staff. They got back underway on May 4 but had more engine troubles in the mid-Atlantic which and forced them to put into Rio for repairs.

The Henrietta finally limped into Valparaíso on July 24, some four months after the bombardment. Doty and Davidson arranged a quick breakfast meeting with Whistler to figure out what to do next.

It did not go well, because Henry Harrison Doty had negotiated one of the worst contracts in the history of contracts.

The Chileans had refused their delivery. They had no need for the torpedoes or rams now that the war was over, and pointed to the line in Doty’s contract which clearly specified that if he failed to deliver on time, then he would get nothing. Less than nothing, even. It actually specified that he would be treated as a “fraudulently bankrupt debtor.” This was all news to Davidson, who had apparently been told they would still be paid for the late delivery. He accused Doty of being a liar and a cheat, and stormed off to enlist in the Peruvian navy.

Doty was also angry, but not with the Chileans. He was angry with Whistler. The artist had spent the last four months painting… and also carousing, smoking cigars, and consuming every last bottle of wine, cognac, sherry, or absinthe he could get his hands on. He was living far beyond the means of his 8s per diem, and somehow he convinced Astive Doty to pay for it all. Heated words were exchanged. Whistler slapped Doty, the two men had to be pulled apart, and they were kicked out of the club. A few days later Doty left the country for good.

Whistler loitered around Valparaíso until mid-September before booking passage back to London aboard the RMS Shannon. He was cranky and irritable the entire time, and decided to take vent his anger on a fellow passenger, a Haitian whom he called “the Marquis de Marmalade.” The Marquis gave offense by… uh, let me check… ah yes, having the temerity to be black while in the presence of James McNeill Whistler.

According to Whistler, he valiantly protected the chastity and honor of the white women aboard the ship by kicking the Marquis across the deck and down a flight of stairs. According to everyone else, Whistler started acting like a racist jerk, got his butt kicked, and wound up confined to quarters with his arm in a sling. When the Shannon’s captain dropped by the following day to lecture his passenger about the proper way to conduct himself, the artist slapped him. So the captain poked Whistler in the eye, knocked him down, and made him say “uncle.”

When the Shannon docked in Southampton Whistler swore out a complaint against the passengers and the crew. The American consulate declined to investigate on the grounds that Whistler was a jerk. (Good on them.)

Whistler then took the train to London, and arrived at Waterloo Station to find Doty waiting for him on the platform.

In the months since their previous meeting, Doty learned why his wife had been covering all of Whistler’s expenses — the two were having an affair. Heated words were exchanged. Whistler slapped Doty and the much larger Doty slapped back. Then Whistler ran away and cowered in the loo while Doty yelled out to everyone who would hear: “This is Whistler, the artist, a scoundrel, a seducer, a betrayer of his trust, mark him.” A few days later Doty formally challenged Whistler to a duel, which the genteel and dignified Southern gentleman ducked like a coward, honor be damned.

Amazingly, that wasn’t the end of it. Flash forward a year and Whistler was still slapping everyone who annoyed him. His latest victims included an unknown Parisian artisan (who got in his way), fellow artist Alphonse LeGros (who owed Whistler money), and his former teacher and brother-in-law Francis Seymour Haden (who told him to stop slapping people).

On top of that, he had been sharpening his poison pen. He loved being witty and didn’t seem to care who he angered in the process. Notably, he called LeGros a “humbug” and Haden a “Pecksniff.” (Can I say that and keep my iTunes clean tag? It’s a character from Martin Chuzzlewit? Just means hypocrite? Whew.)

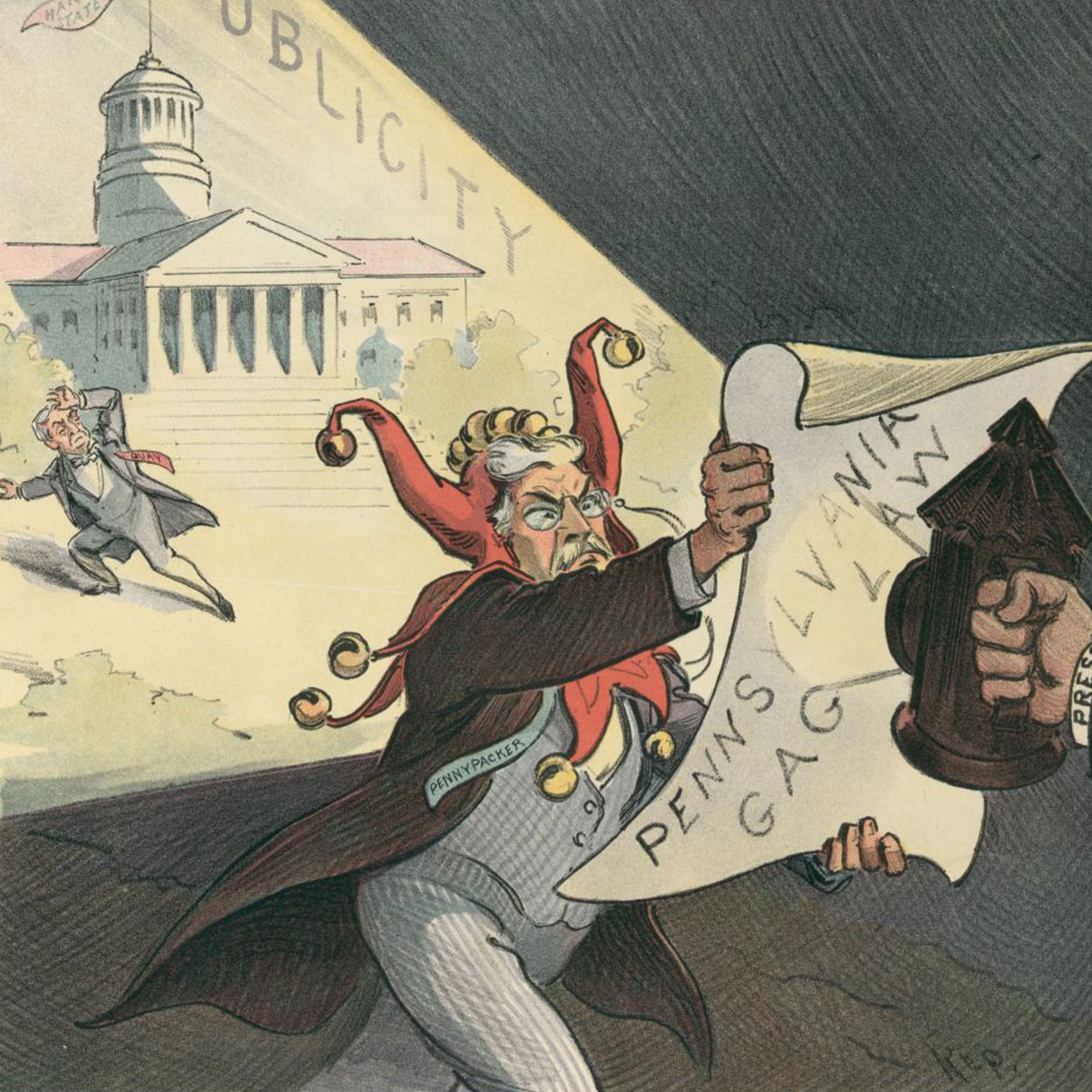

This was all the final straw for Haden, who struck back forcefully… by raising a motion to kick Whistler out of the Burlington Fine Arts Club for conduct unbecoming a gentleman. Okay, that may not seem like much to you, but according to my sources getting kicked out of one’s club was the “ultimate indignity” for a Victorian gentleman.

Haden’s case was simple: Whistler was acting like a petulant child, striking out when he thought he could get away with it and resorting to character assassination when he couldn’t. To back up his argument he produced affidavits from Whistler’s victims, including a lengthy letter from Doty accusing Whistler of being an adulterer.

Whistler’s defenders included Dante Gabriel Rossetti, but even with an eminent pre-Raphaelite painter and famously eloquent poet on their side they couldn’t come up with a better defense than, “Hey, Whistler’s gonna Whistler, that’s just how he rolls, man.” Weak.

The club members were willing to give Whistler a second chance if he seemed even the teeniest bit contrite. Instead he doubled down, insisting that he was not a common thug but a gentleman of principle bound to defend his honor with his fists, and insinuating that his victims deserved the thrashings they had received. Whistler went after Doty with special relish, submitting an affidavit of his own from Davidson that called their former boss a “base villain” of “revolting character.” He also denied being an adulterer — he didn’t deny the affair, he just denied that Henry and Astive Doty were married. That, at least was true — Doty’s legal wife Zippora was still back in Norfolk trying to find her absent husband and serve him with divorce papers. (Good Biblical name, Zippora. Don’t see that much these days. We should bring it back.)

His arguments fell on deaf ears, and on June 11, 1868 Whistler was booted from the Burlington Fine Arts Club by a 19-6 vote. That finally shut him up. At least for a little while.

That Was The End Of It

That was the end of Whistler’s little South American adventure. So let’s ask ourselves: did he accomplish any of his goals?

He did not exactly make his fortune on the trip — honestly, the only reason he was able to break even was because Astive Doty picked up his bar tab. He didn’t exactly cover himself with martial glory, so Willie was still winning that particular sibling rivalry. A nine month break did nothing to help repair any of his personal relationships or personality problems.

On the plus side, the change of scenery did inspire him and change his art for the better.

(I’m going to be talking about art now. If you’re reading this on the website, you’re good! Just keep reading. If you’re listening to the podcast version, you might want to pause and pull up the the website so you can see the paintings I’ll be discussing. If you’re watching the video version, you might actually have to pay attention to the screen for the next few minutes. Novel, I know.)

Whistler had been sketching and painting during the entire trip and returned with a number of canvases that he continued to develop over the coming months and years.

Let’s start with some sketches that Whistler never got around to completing, two landscapes painted from the same vantage point, most likely Whistler’s second-story hotel room. We are looking out over a small pier or wharf and across the harbor to the hills beyond.

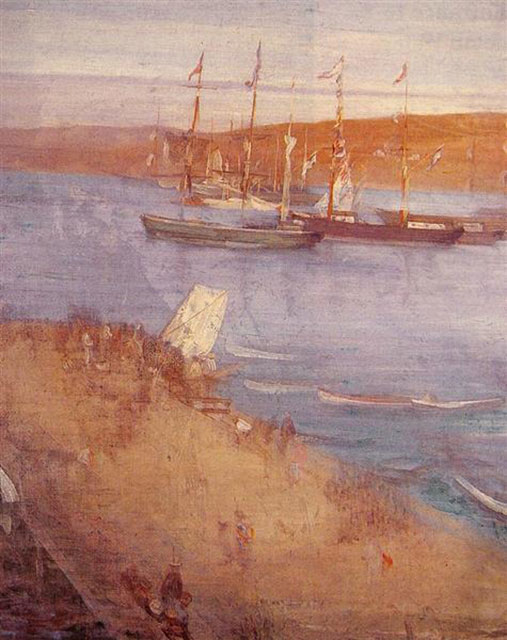

Valparaíso Harbor (1866) comes first, chronologically, and is relatively sedate. The colors are cool and muted, creating a sense of stillness and calm. The waters are as smooth as the brushstrokes used to render them, and their glassy surface is broken only by a small flotilla of ships sailing to the left of the canvas and the open sea. The ships and the landscape are sketchy and loose, but they are not intentionally Impressionistic. That’s just not Whistler’s style. Instead it seems more likely that this is an unfinished sketch or study.

The level of abstraction means that all sense of time and place is lost. This is a frequent complaint about Whistler’s Valparaíso paintings, that he was not interested in the city or its people, that his focus seemed to be the ships and sea, things he could have easily seen at home without having to steam halfway around the world. There is only one detail which fixes the scene to a particular point in time: if you look closely at the ships, you can see national flags furled around their masts. The scene being depicted is the morning of March 30, as the international observers flee the harbor before the Spanish bombardment.

The Morning after the Revolution, Valparaíso (1866) comes second. It is more or less the same composition with several key differences that change the mood from calming to chaotic. The colors are warm and not true to life, the waters choppy, the brushstrokes rapid and angry, and the ships are now steaming to the right. This is the aftermath of the bombardment on March 31, and the international observers are returning to help put out the fires raging through the city.

These pictures are interesting as a dyad, but not terribly compelling on their own. If you’re a student of Whistler or trying to break down his technique, you might be drawn to the economical way he is able to create a ship with a few broad brushstrokes. The rest of us, though, would give these a quick glance and then move on to the next gallery.

Walking into that gallery, we might come across the first painting whistler finished after his return: Symphony in Gray and Green: The Ocean (1866). It’s another variation of the earlier scene from a different vantage point. The pier is still there, as are the ships, but now we are not looking across the harbor to the hills but out to the endless expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

The picture does not live up to its grandiose title. Don’t get me wrong, the composition is quite effective — the angle of the pier, the rhythm of the gray waves, and the arrangement of the ships draw your eye diagonally up and across the canvas to a strip of bright green horizon. The problem is that your eye is being led from nothing to nothing. The sea is not rendered in a particularly interesting way, just sort of an undifferentiated gray mass. The same goes for the boats and the sky. The only particular areas of visual interest are in the fore and mid ground: the pier, a single breaking wave, and few springs of vegetation. These elements are needed to balance the composition, but they do so without actually adding anything meaningful to it.

The ultimate effect is of an endless expanse of gray-green, a popular shade in Victorian times which has fallen out of favor since then. Perhaps it was more appealing under the warm gaslights; right now, all I can say is that it looks faintly nauseating.

Symphony in Gray and Green has some limited charm as a color study, but the representational aspects of the work hold it back. It does make one wonder, though, what Whistler might have been able to achieve if he had taken his work down more abstract paths.

Whistler didn’t though, and thank god he didn’t because his next completed work was Crepuscule in Flesh Color and Green (1866).

Once again, we’re looking at the same scene, the international observers sailing out of the harbor, though this time the foreground has been jettisoned entirely. We are left with only the ships (which have vastly increased in number) the distant hills, and the sea beyond. Compositionally the picture is split almost evenly between sea and sky, with clouds and waves creating almost a balanced yin-yang effect that is only disturbed by the vertical rhythm of masts and sails which bridge the two halves.

What makes Crepuscule striking is the abandonment of realistic color. The sky is perhaps the most naturalistic part of the painting, only a touch more saturated than the real thing. The water, though, is rendered in a luminous jewel-like sea green with the occasional streak of turquoise, far more vivid than anything in nature. The shadows and waves are created through smooth and subtle streaks of peachy yellow and oranges, tones which then seep up through the broad sails of the ships and spread up into the clouds above. The detail, the motion, is created not by shape or form, but almost entirely by these subtle smooth gradations of color.

If Symphony in Gray and Green is drab and depressing, Crepuscule in Flesh Color and Green is atmospheric and enchanting. This, finally, is the breakthrough Whistler was trying to achieve.

Not that he stick with it for long, mind you. Because in Valparaíso Whistler made his first fumbling explorations of the idea which eventually dominated his body of work: the nocturne.

Whistler’s nocturnes are night paintings, but not the dramatic, well-lit chiaroscuro compositions of earlier artists. They are scenes of darkness and twilight, so murky that detail disappears and all one is left with are fleeing blobs of shape and color. Whistler really didn’t fully conceive of the nocturne until the early 1870s, but he retroactively applied the term to several paintings from earlier in his career. The two earliest were ones he had started in Valparaíso.

Or rather, one which was definitely started in Valparaíso, and one that might not have been.

Nocturne: The Solent (1866-1872) is the questionable one, a lost canvas which resurfaced in 1947. Based on the name, art historians assumed that it was a study Whistler worked up on his way to Panama aboard the RMS Solent. However, the style is closer to Whistler’s more mature work, which suggests a later date, and the Solent is also the name for the strait between mainland Britain and the Isle of Wight. As a result the accepted date of painting has been pushed back from 1866 to about 1872.

Like our first two paintings, The Solent is also an unfinished study. There’s an endless sea of bright turquoise, punctuated only by a small strip of land and a few sketchy sailing ships. The whole effect is like an old movie shot day-for-night, quite unlike Whistler’s other nocturnes.

It is, however, one of the most abstract things Whistler ever painted. The waves on the sea are suggested only by a few rippling brushstrokes and a few light smudges, the barest dappling of navy blue. It’s modern, and striking, and beautiful. If it is only a study, it is perhaps a reminder that an abandoned sketch by a great artist can still be great art.

And yet, it’s nothing compared to our final painting: Nocturne in Blue and Gold: Valparaíso (1866). This is immediately recognizable as the same landscape from Valparaíso Harbor and The Morning After the Revolution: there’s the pier, the ships, and the distant hills as seen from Whistler’s second story hotel room.

This time, though, the scene is shrouded in darkness. The pier and the ships almost vanish, their shapes only discernible through subtle tonal variations of blue and black and the occasional dapple of silvery moonlight on the surface of the water. The far shore is further enhanced by distant motes of golden light and a cloud of rising sparks — though it is impossible to tell whether they are ejecta from some distant hearth or rising from some smoldering ruin.

Now this is masterpiece. Every brushstroke is meaningful, every detail important, every color choice carefully considered.

Whistler’s other Valparaíso paintings are intriguing, but incomplete. They are striving for an effect but not quite realizing it. Nocturne in Blue and Gold is attempting to do something completely different, and hitting the ball right out of the park.

The difference is, well, it’s like day and night.

Pun intended.

Connections

There are so many connections to the CSS Shenandoah (“The Sea King”):

- The secret messages Willie Whistler took to the Liverpool were intended for James Dunwoody Bulloch, the Confederacy’s purchasing agent.

- The Shenandoah was only purchased after ambassador Charles Francis Adams prevented the Confederates from purchasing three torpedo rams.

- The reason the United States would not sell arms to the Chileans was because it was in the process of suing neutral Great Britain in international court for helping arm and outfit the Shenandoah, and couldn’t afford to look like a hypocrite.

- The Henrietta‘s captain, Hunter Davidson, made his way back to the United States after the declaration of a general amnesty was for Confederate officers. He took a job with the state of Maryland, fighting poachers as the first commander of their infamous “oyster navy.” One of his successors was James Iridell Waddell, the former commander of the Shenandoah.

One avid collector of Whistler’s work was Sir Hugh Lane, whose untimely death aboard the HMS Lusitania led to a decades-long battle between Great Britain and Ireland over the disposition of his collection (“More Lovely and More Temperate”).

Bibliography

- Bailey, Margin. “Flinging more than a paint pot.” The Art Newspaper, 31 Mar 1999. https://www.theartnewspaper.com/1999/04/01/from-the-secret-archives-of-the-victoria-and-albert-museum-flinging-more-than-a-paint-pot Accessed 4/13/2022.

- Davis, William Columbus. The Last Conquistadores: The Spanish Intervention in Peru and Chile, 1863-1866. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1950.

- Dormet, Richard and MacDonald, Margaret F. James McNeill Whistler. London: Tate Gallery, 1994.

- Harrison, Charles et. al (editors). Art in Theory, 1815-1900. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1998.

- Jones, Virgil Carrington. The Civil War at Sea, Volume 3: The Final Effort. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1962.

- Laver, James. Whistler. London: Faber and Faber, 1930.

- Pennell, Elizabeth Rogers and Pennell, Joseph. The life of James McNeill Whistler. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1911.

- Perry, Milton F. Infernal Machines: The Story of Confederate Submarine and Mine Warfare. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1965.

- Peters, Lisa N. James McNeill Whistler. New York: Smithmark, 1996.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus. “Whistler’s Valparaiso Harbour at the Tate Gallery.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Volume 79, Number 463 (October 1941).

- Smyth, Terry. Australian Confederates: How 42 Australians Joined the Rebel Cause and Fired the Last Shot in the American Civil War. North Sydney, NSW: Ebury Australia, 2015.

- Sutherland, Daniel E. “James McNeill Whistler in Chile: Portrait of the Artist as Arms Dealer.” American Ninteenth Century History, Volume 9, Issue 1 (March 2008).

- Sutherland, Daniel E. Whistler: A Life for Art’s Sake. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

- “Correspondence of James McNeill Whistler.” University of Glasgow. https://www.whistler.arts.gla.ac.uk/correspondence/ Accessed 4/6/2022.

- “Crepuscule in Flesh Color and Green: Valparaiso (1866).” Tate. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/whistler-crepuscule-in-flesh-colour-and-green-valparaiso-n05065 Accessed 4/6/2022.

- “Spar torpedo.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spar_torpedo Accessed 4/18/2022

- “Mexican affairs.” Nashville Union and American, 18 Jan 1866.

- “From our London correspondent.” Leeds Mercury, 6 Mar 1866.

- “Proceedings of a rebel exile.” Sacramento Bee, 3 Apr 1866.

- “Europe.” New York Daily Herald, 22 Apr 1866.

- “Our Bordeaux correspondence.” New York Daily Herald, 29 Apr 1866.

- Sacramento Bee, 7 May 1866.

- “A formidable Chilean cruiser afloat.” Sydney Morning Herald, 30 May 1866.

- “The arts, literature, &c.” Wells Journal, 12 Jan 1867.

- “The Maryland oyster law.” Baltimore Sun, 25 May 1868.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: