I Started a Joke

the difference between laughing with and laughing at

The chief subject of this episode is poetry, and since I have no poetry in my soul I sought out an expert opinion. Whenever you see text on a green background like this it’s poetry expert Dave Blomenberg (#18) speaking.

There are a lot of contenders out there for the title of “Worst Poet of All Time.” Many of them are British. Scotland gave us William Topaz McGonagall, who thought that the only thing a poem had to do was rhyme, scansion be damned. Ireland gave us Amanda McKittrick Ros, who absorbed the bad habits of other poets like a sponge and churned out some of the most putrescent purple poesy the world has ever seen. England gave us Paula Nancy Millstone Jennings, but fortunately for posterity the dolphins left her behind on the old Earth and she was wiped out of existence by a Vogon Constructor Fleet.

But the poet we’re talking about today is American, which means, of course, that she is the best.

By which I mean the worst.

Why don’t we let her tell the story in her own words?

The Author’s Early Life

I will write a sketch of my early life,

It will be of childhood day,

And all who chance to read it,

No criticism, pray.

My childhood days were happy,

And it fills my heart with woe,

To muse o’er the days that have passed by

And the scenes of long ago.

In the days of my early childhood,

Kent County was quite wild,

Especially the towns I lived in

When I was a little child.

I will not speak of my birthplace,

For if you will only look

O’er the little poem, My Childhood Days,

That is in this little book.

I am not ashamed of my birthright,

Though it was of poor estate,

Many a poor person in our land

Has risen to be great.

My parents were poor, I know, kind friends,

But that is no disgrace;

They were honorable and respected

Throughout my native place.

My mother was an invalid,

And was for many a year,

And I being the eldest daughter

Her life I had to cheer.

I had two little sisters,

And a brother which made three,

And dear mother being sickly,

Their care it fell on me.

My parents moved to Algoma

Near twenty-three years ago,

And bought one hundred acres of land,

That’s a good sized farm you know.

It was then a wilderness,

With tall forest trees abound,

And it was four miles from a village,

Or any other town.

And it was two miles from a schoolhouse,

That’s the distance I had to go,

And how many times I traveled

Through summer suns and winter snow.

How well do I remember

Going to school many a morn,

Both in summer and in winter,

Through many a heavy storm.

My heart was gay and happy,

This was ever in my mind,

There is better times a coming,

And I hope some day to find

Myself capable of composing.

It was by heart’s delight,

To compose on a sentimental subject

If it came in my mind just right.

If I went to school half the time,

It was all that I could do;

It seems very strange to me sometimes,

And it may seem strange to you.

It was natural for me to compose,

And put words into rhyme,

And the success of my first work

Is this little song book of mine.

My childhood days have passed and gone,

And it fills my heart with pain

To think that youth will nevermore

Return to me again.

And now kind friends, what I have wrote,

I hope you will pass o’er,

And not criticise as some have done,

Hitherto herebefore.

With “The Author’s Early Life” the title… there’s not much truth in advertising there. She goes into what she’s not going to talk about, and the details of her actual early life are actually pretty scant.

Dave has a point there. I guess I should fill in the blanks.

Julia Ann Davis was born on December 1, 1847 in a “little log shanty” on a farm in Plainfield Township, outside of Grand Rapids, Michigan. She was the oldest of four children. She did not exactly have a pleasant childhood. Before her ninth birthday the family had relocated to more rural Algoma, one of her younger sisters had died, and her mother contracted an unknown disease (probably tuberculosis) that left her bedridden. Julia had to drop out of school and become the woman of the house. In 1864 at the age of 17 she got “spliced” to local farmer Frederick Franklin Moore, one year her senior.

Julia Ann Moore was a very busy woman. When she was not choring on the family farm she was working in the family tool store, or tending house, or rearing her ten children. And yet she never let her crushing workload or her lack of formal education dissuade her from pursuing her true love: poetry.

Verse flowed from Julia freely and easily. When she was inspired she could start composing while drinking her morning cup of coffee, and have the finished work ready before the dinner bell rang. It helped that she kept things simple, composing most of her works in a simple ballad meter or composing to the tunes of then-popular songs. It also helped that she didn’t believe in editing, mostly because she didn’t have time for editing.

Julia received most of her inspiration from the obituary page of the local newspaper, a never-ending parade of misery that could be mined for cheap sentiment and a few verses. She composed countless elegies for the men, woman, and children of Grand Rapids who had been taken from this world too soon. Every once in a while she turned out a real banger and would mail it to the newspaper — back in those days, newspapers would print anything if they had empty columns that needed to be filled.

Well, it wasn’t long before one of her poems was the perfect length to fill one of those blanks: “William Upson,” a memorial tribute to a local boy who had died fighting in the Union Army.

William Upson

Come all good people, far and near,

Oh, come and see what you can hear,

It’s of a young man, true and brave,

Who is now sleeping in his grave.

Now, William Upson was his name —

If it’s not that it’s all the same —

He did enlist in the cruel strife,

And it caused him to lose his life.

He was Jesse Upson’s eldest son,

His father loved his noble son;

This son was nineteen years of age,

In the rebellion he engaged.

His father said that he might go,

But his dear mother she said no.

“Stay at home, dear Billy,” she said,

But oh, she could not turn his head.

For go he would, and go he did —

He would not do as his mother bid,

For he went away down South, there

Where he could not have his mother’s care.

He went to Nashville, Tennessee,

There his kind friends he could not see;

He died among strangers, far away,

They knew not where his body lay.

He was taken sick and lived four weeks,

And oh, how his parents weep,

But now they must in sorrow mourn,

Billy has gone to his heaven home.

If his mother could have seen her son,

For she loved him, her darling one,

If she could heard his dying prayer,

It would ease her heart till she met him there.

It would relieved his mother’s heart,

To have seen her son from this world depart,

And hear his noble words of love,

As he left this world for that above.

It will relieve his mother’s heart,

That her son is laid in our grave yard;

Now she knows that his grave is near,

She will not shed so many tears.

She knows not that it was her son,

His coffin could not be opened —

It might be some one in his place,

For she could not see his noble face.

He enrolled in eighteen sixty-three,

The next day after Christmas eve;

He died in eighteen sixty-four,

Twenty-third of March, as I was told.

You might have noticed that “William Upson” is very, very bad.

There are quatrains that go nowhere. The lines are uneven and have an award cadence. Many of the rhymes are forced, like mourn/home, heart/yard, four/told. The serious tone is undercut by lines that are almost silly, like, “William Upson was his name — / If it’s not that it’s all the same –“

As for the subject matter…

It tends to stick to the surface, which makes things easier to understand. It reminds me of something that one of my students said when we were in a workshop and I had pulled out some bad verse that was really general and didn’t really go into detail and you didn’t really know what was going on because it was badly written. I asked, “What do you like about this?” just to start the discussion. One of the first responses was “I like how it’s so general, that way I can make it mean what I want it to.” That may be one of the reasons why bad writing can be popular. It doesn’t take a lot to digest and you can just make it mean what you want to. It’s easy emotion without a lot of work to get there.

The whole identity bit is sort of surprising. The grieving mother doesn’t even know whether or not it’s her son in the casket. That could have been the door to a successful poem! There’s this question of identity, especially with war dead, depending on how horrible the injuries were. And of course this is a closed casket funeral she’s talking about here in this verse. She never goes there.

The speaker of the verse here, towards the end, is talking about his dying prayer… which the speaker would have heard! She can actually imagine it! She never says it. She never goes there.

All these possible doors that open to something deeper, bigger, with more gravity and impact… she’s fine leaving those doors shut and just moves on to, with the end… and this is a classic case of her cutting herself off at the ankle… you’ve got this verse, and then she doesn’t have the last stanza scan. “He enrolled in 1863 / the next day after Christmas eve / He died in eighteen sixty-four / the twenty-third of March as I was told.” How is that as an ending? And it doesn’t even scan.

So yeah, “William Upson” was hardly a rousing success.

So of course the people of Grand Rapids loved it.

Why do people like things that are objectively bad? It turns out for many people “quality” is not something they look for in the arts. They just want to feel something, and it turns out that bad things can do that just as well as good things, precisely because they are familiar, easy, and unchallenging.

You’ve got a lot of things that don’t require a lot of deep thought or introspection. It’s not challenging the way that poetry has a reputation for being. It skates along the surface. That sort of makes it easy to read and digest.

One of her big things is ballad meter. Generally line breaks can be different but you’ve got iambic tetrameter, so it’s four beats per measure in the first line, and then iambic trimeter, which is three beats. “Dah de dah de dah de dah, dah de dah de dah.” That tends to be her opening line or two. She immediately demonstrates that she can’t keep that up in every single verse… I don’t know why, but she just can’t keep it up from line three on, poor thing. This is a familiar form from hymns. As well as “Gilligan’s Island.” The “Gilligan’s Island” theme is in ballad meter — four lines, then three. All of this is ingrained in the American readership. It’s something she can just tap into. It doesn’t go into any detail or depth, but it’s something the readership is familiar with and can just plow through.

I’ll add, there’s nothing inherently wrong with this attitude. The primary purpose of entertainment is to be entertaining. It does not have to be ground-breaking, genre-defining, great, or even good to fulfill the brief. I do not watch CSI or Leverage or Storage Wars because they make me think. I watch them because I just got home from work and I don’t want to think, and because I don’t have to watch them too closely to follow what’s going on.

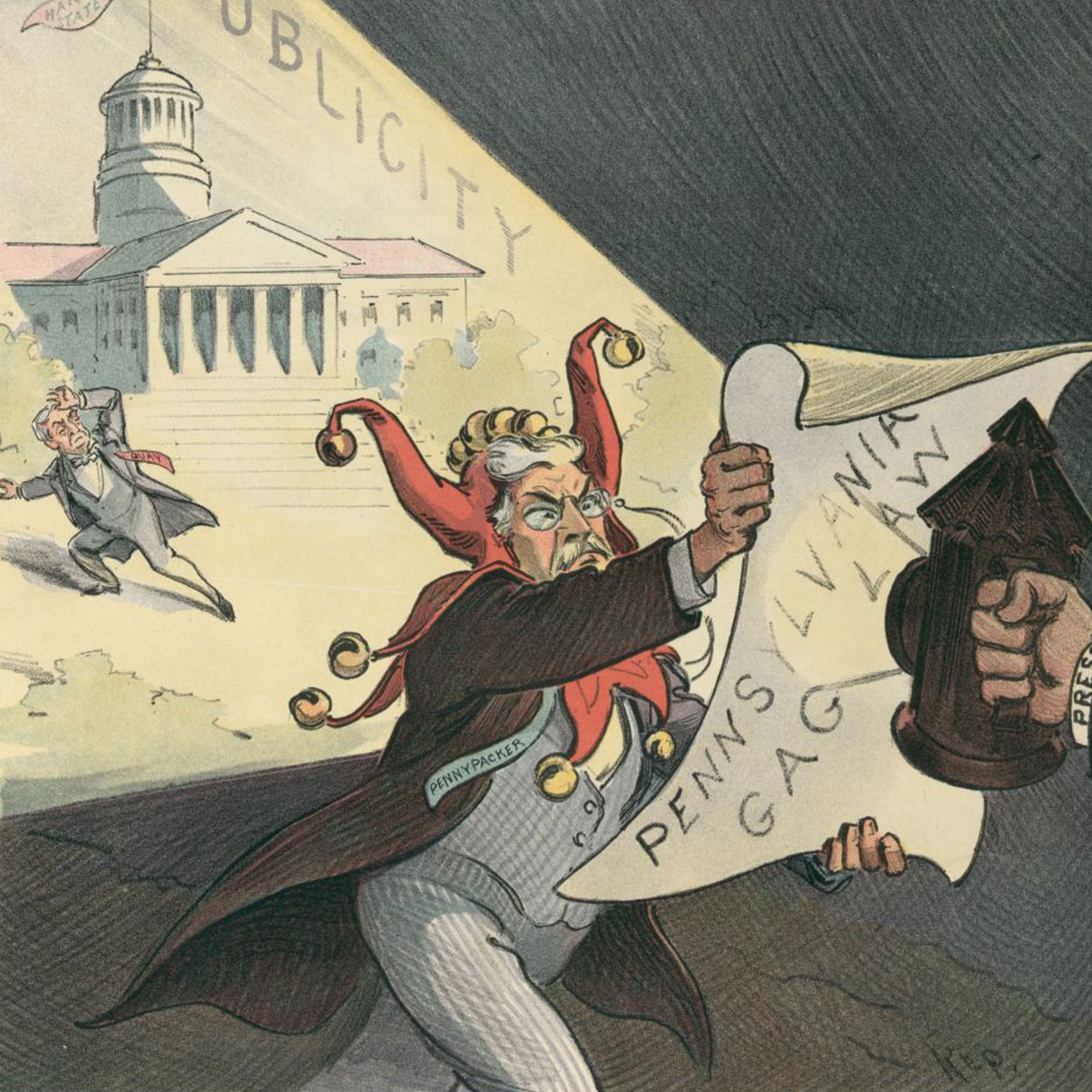

Of course, there are also people who love things precisely because they are bad. Many of them are just haters, who get joy from tearing other things down. There are others, though, for whom Julia’s failure to follow standard poetic forms, her inability to maintain a consistent style or tone, her wildly inappropriate approach to her subject matter… these gave them a jolt of cognitive dissonance that tickled their funny bone. We have a name for these people: hipsters.

It turns out there were plenty of hipsters in Grand Rapids, even in the 1870s. They loved Julia’s work ironically.

Folklorist Walter Blair summed up this point of view nicely: “If these songs were only a little closer to the conventional modes of metre, rhyme, thought and expression they would not impress us at all. Touched, however, by the magic wand of genius, the novel works of this great poet cause readers to slump down in their chairs, hold their agitated and aching sides, wipe tears from brimming eyes, and fill the air with the sounds of distinctly raucous laughter.”

So yeah, the people of Grand Rapids loved Julia’s poems, for one reason or another. And she loved them right back. To the point where she even wrote a poem for them.

Grand Rapids

Wild roved the Indians once

On the banks of Grand River,

And they built their little huts

Down by that flowing river.

In a pleasant valley fair,

Where flows the river rapid,

An Indian village once was there,

Where now stands Grand Rapids.

Indian girls and boys were seen,

With their bow and quiver,

Riding in their light canoes

Up and down the river.

Their hearts were full of joy,

Happy voices singing

Made music with forest birds,

They kept the valley ringing.

Indians have left and gone

Beyond the Mississippi.

They called the river Owashtenong

Where stands this pleasant city.

Louis Campau the first white man

Bought land in Grand Rapids.

He lived and died, an honored man

By people of Grand Rapids.

When Campau came to the valley

No bridge was across the river;

Indians in their light canoes

Rowed them o’er the water.

Railroads now from every way

Run through the city, Grand Rapids;

The largest town in west Michigan

Is the city of Grand Rapids.

That skating on the surface… The synopsis of that poem is “Indians were here once but now we’ve got Grand Rapids.” That’s about it.

To be fair, Dave, she also managed to rhyme the word “rapids” with itself three times.

I know. Yes. To give her a little bit of props, there’s a term for that called “rich rhyme” where the word rhymes with itself in a stanza. We’ll give her that at least.

The Sentimental Song Book

Julia kept on writing poems and eventually built up a solid body of work. In 1876 she collected thirty-four of her greatest hits and contracted local publisher C.M. Loomis to print a small chapbook. The Sentimental Song Book is packed full of poems on every subject imaginable. There were poems about love, poems about motherhood, poems about mortality, poems about the history of Rockford, MI, poems about the Temperance movement and bimetallism and the Centennial and the American flag and of course, more death and destruction than you could shake a stick at.

Ashtabula Disaster

Have you heard of the dreadful fate

Of Mr. P. P. Bliss and wife?

Of their death I will relate,

And also others lost their life;

Ashtabula Bridge disaster,

Where so many people died

Without a thought that destruction

Would plunge them ‘neath the wheel of tide.

CHORUS:

Swiftly passed the engine’s call,

Hastening souls on to death,

Warning not one of them all;

It brought despair right and left.

Among the ruins are many friends,

Crushed to death amidst the roar;

On one thread all may depend,

And hope they’ve reached the other shore.

P. P. Bliss showed great devotion

To his faithful wife, his pride,

When he saw that she must perish,

He died a martyr by her side.

P. P. Bliss went home above —

Left all friends, earth and fame,

To rest in God’s holy love;

Left on earth his work and name.

The people love his work by numbers,

It is read by great and small,

He by it will be remembered,

He has left it for us all.

His good name from time to time

Will rise on land and sea;

It is known in distant climes,

Let it echo wide and free.

One good man among the number,

Found sweet rest in a short time,

His weary soul may sweetly slumber

Within the vale, heaven sublime.

Destruction lay on every side,

Confusion, fire and despair;

No help, no hope, so they died,

Two hundred people over there.

Many ties was there broken,

Many a heart was filled with pain,

Each one left a little token,

For above they live again.

Poor thing, Mr. P.P. Bliss and wife. To be immortalized as P.P. Bliss and wife. I was looking him up and they never found him, apparently, in the train wreckage.

She doesn’t really go into any gory details about the mechanics of the Ashtabula train disaster. When we read through them, that’s pretty horrific stuff. She skates along the surface and makes a horrible situation kind of digestible, in a way, I suppose.

In spite of all the morbid death and destruction (or maybe because of it) The Sentimental Song Book sold quite well to the hipsters of Grand Rapids. Julia actually made a profit… well, a small profit. A very small profit. About $29. That wasn’t exactly encouraging, but let’s be honest, even today many poets don’t break even on their work.

Thankfully, there are other ways for artists to profit from the arts. In April 1877, posters went up around Grand Rapids announcing a very special event:

Powers Opera House

One night only,

Tuesday, Evening, May 1, 1877.First appearance in Grand Rapids, of Kent County’s talented poetess, Mrs. Julia A. Moore, who will give a reading of her select poems. Will also sing some of her choice productions; among the rest the soul-stirring ballad, “The Beautiful Twenty-Second.”

Seats secured at Geo. A. Hall’s, in the Arcade, on and after Friday morning, April 27. Price of admission to Parquette, Parquette Circle, and Dress Circle, 35 Cents. Gallery, 25 Cents. A fine orchestra engaged. Secure seats early to avoid a rush.

The hipsters organizing the reading anticipated a total sellout.

They were sorely disappointed. They sold about 150 tickets, which just barely covered the cost of renting the opera house. In the end they papered the house by giving away free tickets, and on Tuesday, May 1 the Powers Opera House was packed.

At the appointed hour Julia took to the stage and was greeted by a thunderous round of applause. She made herself comfortable on a large sofa, took out a copy of The Sentimental Song Book, and began reading poems out loud to the accompaniment of Professor Anderson and his orchestra.

It didn’t exactly go smoothly. The orchestra was off-key and so loud that it was hard to hear Julia. When she could be heard, her thick accent and half-singing, half-speaking style made it hard to understand her. The audience liked it anyway. They dutifully applauded at the end of each poem and rose to their feet when the poet launched into her big finale: a patriotic ode to Washington’s Birthday, “The Beautiful Twenty-Second.”

The Beautiful Twenty-Second

The people in this nation,

Have kept for many years,

February twenty-second,

That day we love it dear.

It’s our forefather’s birthday,

Brave, noble Washington;

And may we ever keep it,

Through all the years to come.

CHORUS:

Beautiful twenty-second,

Beautiful twenty-second,

May the people ever keep it,

Beautiful twenty-second.

One of the constitution builders,

Was that brave, noble man,

He fought under that dear flag

That’s loved throughout our land.

He went through many battles,

He fought for liberty,

That this glorious republic

A nation great may be.

Oh, keep the twenty-second,

In honor to his name,

Who fought to gain our freedom

From England’s British chains.

Now he is sweetly sleeping,

Brave, noble Washington,

May the people not forget him,

Columbia’s noblest son.

When I was teaching poetry workshops at Purdue I talked about how there’s a difference between verse and poetry. Verse is a structure, and poetry is something else. Poetry is condensed language, and this is really not condensed. You try to come up with a synopsis of the poem and a lot of them are “he died” or “he fought to make the country great” if you’re looking at “The Beautiful Twenty-Second”… which is about Washington’s Birthday, but that’s all we really know. It’s not like we pick up anything.

The audience of hipsters seemed to like it, though. They gave her a standing ovation as the organizers presented Julia with a lovely bouquet of brassica oleracea (that’s cabbage, if your Latin is rusty).

Of course, the haters were always going to hate. The Grand Rapids Daily Morning Democrat‘s arts beat reporter was not exactly kind.

What defiance of all rules of grammar, elocution, sense, rhetoric, eloquences, oratory, inflection, compass, quality, execution, variety, cadence, vivacity, emotion, intelligibility, articulation, emphasis, accent, antithetical stress, modulation, pitch, gesture, and others, did this untutored plebeian indulge in.

The Sweet Singer of Michigan Salutes the Public

Well, you can’t keep a unique talent Julia’s hidden for long. Eventually a copy of The Sentimental Song Book made its way from Grand Rapids to Cleveland, where it came into the possession of photographer James F. Ryder. He knew right away that he’d found something extraordinary.

It is a well-known fact among critics that two kinds of poetry, and only two, go in the public estimation and are worth anything in the market. One kind is the very good and the other is the very bad.

James F. Ryder, Voigtlander and I

Ryder acquired the rights Julia’s book and issued a new edition with a new title: The Sweet Singer of Michigan Salutes the Public. Then he sent a free copy to every journalist he could think of, with the following cover letter:

Having been honored by the gifted lady of Michigan in being entrusted with the publication of her poems, I give myself the pleasure of handing you herewith a copy of the same, with my respectful compliments… It will prove a healthy lift to the overtaxed brain, it may divert the despondent from suicide. It should enable the reader to forget the “stringency” and guide the thoughts into pleasanter channels. It opens a new lead in literature, and is sure to carry conviction. It must be productive of good to humanity. If you have the good of your fellow creatures at heart, and would contribute your mite towards putting them in the way of finding this little volume, the thanks of a grateful people (including authoress and publisher) would be yours.

It worked. Journalists love free stuff, especially when they use that free stuff to fill empty columns. Some penned sarcastic paeans to the Sweet Singer’s work. Other wrote savage reviews. Bill Nye (not the science guy, but a Denver Post columnist who was the Dave Barry of the 1870s) wrote several essays on Julia, full of some truly savage mockery.

Julia is worse than a gatling gun; I have counted twenty-one killed and nine wounded in the small volume she has given the public… I think that Julia takes advantage of her poetic license. A poetic license, as I understand it, simply allows the poet to jump the 15 over the 14 in order to bring in the proper order, but it does not allow the writer to usurp the management of the entire system of worlds… We have too many poets in our glorious republic who ought to be peeling the epidermis off a bull train, and too many poetesses who would succeed better boiling soap-grease, or spixing a 6×8 patch on the quarter-deck of a faithful husband’s overalls.

Bill Nye, Bill Nye and Boomerang

Well, you couldn’t ask for better publicity.

You couldn’t ask for better publicity. People rushed out to buy copies of The Sweet Singer of Michigan Salutes the Public just to see what all the fuss was about. They laughed at Julia’s poems, and Ryder laughed all the way to the bank.

The public demanded to know about the poetry sensation that was sweeping the nation. In January 1878 the Chicago Inter-Ocean sent reporter E.A. Stowe out to Algoma, where he landed an exclusive interview with the Sweet Singer herself.

The interview is refreshingly straightforward. Stowe does not go out of the way to mock his subject. He is content to sit back, ask questions, and let Julia’s responses do all the heavy lifting. He teased out most of the biographical information we have about Julia’s early life, information about her family, and her thoughtful musings on any number of subjects. It is equal parts insightful and comedy gold.

STOWE: Can you sit down or write any time, or does this wonderful gift come by inspiration?

MOORE: Sometimes, when my children are cross, and my old man — that’s my husband — don’t feel very well, I can’t write anything good at all. But when everything is right I can compose like sixty….

STOWE: Did any of your ancestors possess this wonderful genius for poetry?

MOORE: Nary a one of them. I was the only one that could ever write a poem to save their necks.

STOWE: You must make considerable money from the sale of your books.

MOORE: No, I don’t make very much. Ryder makes the money. The most I make is what I sell myself. I have sold pretty near $29 worth of the books to the neighbors around here to send to their friends. As soon as I can go through the country reading my poems I think I can sell more of the books…

STOWE: Mrs. Moore, which of the great poets do you most admire?

MOORE: I can’t say, for I never read any of ’em. I like my Sentimental Song Book best for all I know.

Stowe’s interview was widely reprinted, and was quickly followed by numerous other interviews. Mind you, no reporter was actually willing to trek all the way out to Algoma to conduct an interview, and Julia certainly wasn’t coming down from Algoma just to talk to a reporter. Almost every interview after that first one was entirely fabricated, and guaranteed to be packed full of fake quotes that made their subject sound like a fool.

A Few Choice Words to the Public

The Sweet Singer of Michigan Salutes the Public was a rousing success. To capitalize on its popularity, a second volume of Julia’s poetry was rushed to market.

Many artists have difficulty following up a smash success, and Julia was no difficult. According to J.F. Ryder she listened to the critics and starting doing things like “editing” and “revisions.” Worried that his meal ticket would improve from “bad” to “mediocre” and ruin things for both of them, Ryder advised her to not overthink things and dash off poems with little thought, in the style of “Byron and all the great geniuses, presumably.”

That seemed to do the trick, and Julia’s new poems quickly reached new levels of badness. In early 1878 they were published as A Few Choice Words to the Public, with New and Original Poems.

The book opens up with an essay by Julia, defending herself from the critics who savaged her previous book and quoting the critics who had praised her (she doesn’t seem to have understood that the praise was sarcastic). There are also a few paragraphs about how great farmers are, which were apparently inserted to placate her husband Fred. Apparently he wasn’t worried that his wife’s bad poetry was turning their family into a laughingstock, but was worried that people thought her she had to turn to poetry because he couldn’t put food on the table.

That defensive tone also made its way into the poems themselves.

To My Friends and Critics

Come all you friends and critics,

And listen to my song,

A word I will say to you,

It will not take me long,

The people talks about me,

They’ve nothing else to do

But to criticise their neighbors,

And they have me now in view.

Perhaps they talk for meanness,

And perhaps it is in jest,

If they leave out their freeness

It would suit me now the best,

To keep the good old maxim

I find it hard to do,

That is to do to others

As you wish them do to you.

Perhaps you’ve read the papers

Containing my interview;

I hope you kind good people

Will not believe it true.

Some Editors of the papers

They thought it would be wise

To write a column about me,

So they filled it up with lies.

The papers have ridiculed me

A year and a half or more.

Such slander as the interview

I never read before.

Some reporters and editors

Are versed in telling lies.

Others it seems are willing

To let industry rise.

The people of good judgment

Will read the papers through,

And not rely on its truth

Without a candid view.

My first attempt at literature

Is the “Sweet Singer” by name,

I wrote that book without a thought

Of the future, or of fame.

Dear Friends, I write for money,

With a kind heart and hand,

I wish to make no Enemies

Throughout my native land.

Kind friends, now I close my rhyme,

And lay my pen aside,

Between me and my critics

I leave you to decide.

In terms of her critical response there’s a lot to hold hands with Amanda McKittrick Ros, where she loved to rail against her critics. You have a lot of things where her critics will gripe about her so there’s a lot of gripes against criticism…

She’s got a really unfortunate line break in “To My Friends and Critics” where the line actually just reads, “I wrote that book without a thought.” That’s a bad line. Don’t want to do that, especially when you’re talking about people criticizing your work.

The rest of the poems are more of the same, on subjects as varied as Andrew Jackson and croquet the Great Chicago Fire and Temperance and yellow fever and as always more dead children than you could shake a stick at. Julia also seemed to have Byron on the brain after Ryder’s pep talk, because she definitely had some thoughts on the subject.

Sketch of Lord Byron’s Life

“Lord Byron” was an Englishman

A poet I believe,

His first works in old England

Was poorly received.

Perhaps it was “Lord Byron’s” fault

And perhaps it was not.

His life was full of misfortunes,

Ah, strange was his lot.

The character of “Lord Byron”

Was of a low degree,

Caused by his reckless conduct,

And bad company.

He sprung from an ancient house,

Noble, but poor, indeed.

His career on earth, was marred

By his own misdeeds.

Generous and tender hearted,

Affectionate by extreme,

In temper he was wayward,

A poor “Lord” without means;

Ah, he was a handsome fellow

With great poetic skill,

His great intellectual powers

He could use at his will.

He was a sad child of nature,

Of fortune and of fame;

Also sad child to society,

For nothing did he gain

But slander and ridicule,

Throughout his native land.

Thus the “poet of the passions,”

Lived, unappreciated, man.

Yet at the age of 24,

“Lord Byron” then had gained

The highest, highest, pinnacle

Of literary fame.

Ah, he had such violent passions

They was beyond his control,

Yet the public with its justice,

Sometimes would him extol.

Sometimes again “Lord Byron”

Was censured by the press,

Such obloquy, he could not endure,

So he done what was the best.

He left his native country,

This great unhappy man;

The only wish he had, “’tis said,”

He might die, sword in hand.

He had joined the Grecian Army;

This man of delicate frame;

And there he died in a distant land,

And left on earth his fame.

“Lord Byron’s” age was 36 years,

Then closed the sad career,

Of the most celebrated “Englishman”

Of the nineteenth century.

The dis poem.

She’s got lots of gripes, so she’s sort of the Taylor Swift of verse. That too holds hand with people like Amanda McKittrick Ros, where they don’t like certain people and they’re going to let people know about it in a very general way.

[sigh] But Byron actually scans, that’s the thing. He actually scans. She doesn’t.

To promote A Few Choice Words to the Public, Julia went on a book tour that took her from Cleveland to Chicago to Grand Rapids. The honoraria barely covered her expenses, but she convinced herself that it would all be worth it in the end.

She was wrong. This time the crowds were subtly but undeniably different. They were no longer there to laugh at the poems. They were there to laugh at Julia. It all came to a head on December 23, 1878, when Julia Ann Moore held her final poetry reading in Grand Rapids.

Initially it seemed like a normal gig, but it turned sour fast. The organizers had her dress in an outfit that made her look ludicrous, sat her on an over-large sofa that she kept falling over in, and had the orchestra ham it up like they were the accompaniment for a cheap burlesque. The audience loved it, but the laughter was cruel and mocking.

Eventually, Julia could take it no more and snapped. “You people paid fifty cents each to see a fool, but I got fifty dollars to look at a house full of fools.” Then she stormed off the stage.

That was enough for Fred. He put his foot down and decreed that his wife would have to stop publishing poems. Julia, for once, didn’t argue.

In 1882 the Moores attempted to put Julia’s poetry career behind them by moving to remote Manton, where they continued to farm and ran several small businesses, including a sawmill. The family was well-liked by the community, who vigorously protected the Moores’ privacy and turned away countless reporters who trekked out to Manton in vain attempts to research “where are they now” stories.

Julia’s fleeting success inspired a small army of imitators who tried to fill her shoes. The leading contenders included ludicrous characters like Fred H. Yapple; Bloodgood H. Cutter “The Long Island Farmer Poet”; and J.B. Smiley “the Rip-Roaring Rhymer of Kalamazoo.” Some of them were genuinely bad, others were just faking it, but none of them were as interestingly bad as Julia and today they have all been justly forgotten.

Fred Moore died unexpectedly in 1914. After his passing it became clear that Julia had never stopped writing, just publishing. She eventually published a poem or two in the Manton Tribune, but kept most of her output private. When she passed on June 5, 1920 the Boston Evening Transcript was surprisingly kind in their obituary: “In absolute good faith she had given the world her poem creations, and little did she realize that many poets of greater worth have done the same and fared far worse.”

I Finally Died

Is there a right way to engage with bad art?

Hardly the most pressing issue, I know. And yet, as a child of Mystery Science Theater 3000 I have been conditioned to ironically likes bad things, whether those are movies like Unmasking the Idol, books like the Nick Carter: Killmaster series, or the musical output of Mr. William Shatner. The answer to this question is vitally important to me and my perception of myself as a good person.

I know there’s a wrong way to do it, and it’s clearly the way her so-called fans did back in 1878. If you see something bad and your first instinct is to mock the person who made it, you’re not a critic, you’re not some aesthete, you’re just a hater.

Creating something is hard, and sharing a creation with the world is even harder. The creator is literally putting a piece of themselves out there to be seen by all. I’m not saying you should pretend to like their work — the best reaction is an honest reaction, so if it makes you laugh, laugh; if it makes you cry, cry. But you should also remember that the flaws of the art are not the flaws of the artist. Its badness is not their badness. You are laughing at the poem, not the poet.

So celebrate the act of creating. Celebrate the creator. Feel free to laugh at the creation. (And maybe when the creator isn’t around.)

Fortunately for Julia Ann Moore, she had a fan like that back in the day, one who could laugh at the poems and love their author. Fortunately for us, his name was Mark Twain.

I have been reading the poems of Mrs. Julia A. Moore, again, and I find in them the same grace and melody that attracted me when they were first published, twenty years ago, and have held me in happy bonds ever since. ‘The Sentimental Song Book’ has long been out of print, and has been forgotten by the world in general, but not by me. I carry it with me always – it and Goldsmith’s deathless story… Indeed, it has the same deep charm for me that the Vicar of Wakefield has, and I find in it the same subtle touch – the touch that makes an intentionally humorous episode pathetic and an intentionally pathetic one funny… I have read her book through twice today, with the purpose of determining which of her pieces has most merit, and I am persuaded that for wide grasp and sustained power, ‘William Upson’ may claim first place.

Mark Twain, Following the Equator

Twain even paid Julia the ultimate compliment by writing her into one of his books. In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn we briefly encounter the Grangerford family, whose late daughter Emmeline writes truly awful poetry in “tribute” to the deceased.

The neighbors said it was the doctor first, then Emmeline, then the undertaker — the undertaker never got in ahead of Emmeline but once, and then she hung fire on a rhyme for the dead person’s name, which was Whistler. She warn’t ever the same after that; she never complained, but she kinder pined away and did not live long…

Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

Just for good measure, Twain also out-Julia’d Julia by writing a pitch-perfect imitation of one of her poems.

Ode to Stephen Dowling Bots, Dec’d

And did young Stephen sicken,

And did young Stephen die?

And did the sad hearts thicken,

And did the mourners cry?

No; such was not the fate of

Young Stephen Dowling Bots;

Though sad hearts round him thickened,

‘Twas not from sickness’ shots.

No whooping-cough did rack his frame,

Nor measles drear, with spots;

Not these impaired the sacred name

Of Stephen Dowling Bots.

Despised love struck not with woe

That head of curly knots,

Nor stomach troubles laid him low,

Young Stephen Dowling Bots.

O no. Then list with tearful eye,

Whilst I his fate do tell.

His soul did from this cold world fly,

By falling down a well.

They got him out and emptied him;

Alas it was too late;

His spirit was gone for to sport aloft

In the realms of the good and great.

Thanks to Mark Twain and other like-minded admirers, the Sweet Singer of Michigan was never truly forgotten. Her work has been sporadically in print ever since, waiting to be rediscovered and enjoyed by new generations. Over the years her admirers have included Ogden Nash, who claimed she inspired him to become a “great bad poet” instead of a “bad good poet.”

In the 1925 her poem “Leave off the Agony in Style” was rewritten by Vernon Dalhart into a goofy novelty song, “Putting on the Style.” Dalhart’s version became an Appalachian standard but didn’t really catch on nationally. Thirty years later, though, it was a #1 hit for “The King of Skiffle” himself, Mr. Lonnie Donegan.

Leave Off the Agony in Style

Come all ye good people, listen to me, pray,

While I speak of fashion and style of today;

If you will notice, kind hearts it will beguile,

To keep in fashion and putting on style.

CHORUS:

Leave off the agony, leave off style,

Unless you’ve got money by you all the while,

If you’ll look about you you’ll often have to smile,

To see so many people putting on style.

People in this country they think it is the best;

They work hard for money and lay it out in dress;

They think of the future with a pleasant smile,

And lay by no money while putting on style.

Some of the people will dress up so fine,

Will go out in company and have a pleasant time.

Will rob themselves of food, perhaps, all the while,

Sake of following fashions and putting on style.

I love to see the people dress neat and clean,

Likewise follow fashions, but not extremes;

Some friends will find it better in future awhile,

To lay by some money while putting on style.

Gentlemen on the jury decides the criminal’s fate;

I pray you turn from wickedness before it is too late;

Sad, indeed, would be your friends to hear your name reviled,

Better be truly honest though putting on style.

Leave off the agony, leave off style,

Unless you’ve got money by you all the while.

If you look about you you’ll often have to smile,

To see so many poor people putting on style.

Does the Rip-Roaring Rhymer of Kalamazoo have a #1 hit to his credit? I think not.

Case closed.

Connections

Special thanks to all those who contributed their voice talents to this episode, including #7 Dorothy Sibole, Eric Leslie, #23 David L. White, #29 Greg Armstrong, #8 Sam Link, Steve White, Kristen Harkness, and Richard Le Poidevin.

Connections

There’s other episode where I asked friends of the podcast to do dramatic readings — that’s the bonus episode “Grandiose But Straightforward”, about a strange little corner of Dungeons & Dragons history.

Sources

- Beagle, Peter S. “Spook.” The Essential Peter S. Beagle, Volume I: Lila the Werewolf and Other Stories. San Francisco: Tachyon Publications, 2023.

- Greenly, A.H. “The Sweet Singer of Michigan Biographically Considered.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, Volume 39, Number 2 (1945).

- Hayden, Bradley. “In Memoriam Humor: Julia Moore and the Western Michigan Poets.” The English Journal, Volume 72, Number 5 (September 1983).

- Michaelson, L.W. “Four Emmeline Grangerfords.” Mark Twain Journal, Volume 11, Number 3 (Fall 1961).

- Moore, Julia Ann. The Sentimental Song Book. New York: Platt & Peck, 1912.

- Moore, Julia Ann. The Sweet Singer of Michigan. Chicago: Pascal Covici, 1928.

- Moore, Julia Ann. A Few Choice Words to the Public, With New and Original Poems. Grand Grapids: C.M. Loomis, 1878.

- Nye, Bill. Bill Nye and Boomerang. Chicago: Morrill, Higgins & Co., 1892.

- Parsons, Nicholas. The Joy of Bad Verse. London: Collins, 1988.

- Petras, Kathryn and Peras, Ross. Very Bad Poetry. New York: Vintage Books, 1997.

- Riedlinger, Thomas J. (editor). Mortal Refrains: The Complete Collected Poetry, Prose, and Songs of Julia A. Moore, the Sweet Singer of Michigan. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 1998.

- Ryder, James F. Voigtländer and I: In Pursuit of Shadow Catching. Cleveland: Cleveland Printing & Publishing Co., 1902.

- Sestero, Greg, and Bissell, Tom. The Disaster Artist. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013.

- Sontag, Susan. “Notes on Camp.” Against Interpretation. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966.

- Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. New York: Penguin Books, 2014.

- Twain, Mark. Following the Equator. Washington, DC: National Geographic Adventure Classics, 2005.

- Umland, Rudolph. “The Blessed Sweet Singer.” Prairie Schooner, Volume 8, Number 4 (Fall 1934).

- “Varieties.” New England Journal of Education, Volume 7, Number 13 (March 28, 1878).

- “The Sweet Singer of Michigan.” Chicago Inter Ocean, 12 Oct 1877.

- “The Sweet Singer of Michigan.” Lancaster Intelligencer-Journal, 13 Oct 1877.

- “The Sweet Singer of Michigan.” Chicago Tribune, 20 Oct 1877.

- “Personal.” Chicago Tribune, 21 Nov 1877.

- Stowe, E.A. “Michigan’s nightingale.” Chicago Inter Ocean, 12 Jan 1878.

- “The Sweet Singer’s retort.” Chicago Tribune, 1 Feb 1878.

- “Joy to the world.” Chicago Inter Ocean, 16 Feb 1878.

- Rubin, Neal. “Bad poet? Then show it!” Detroit Free Press, 31 Mar 1993.

- Moses, Alexander R. “Bad is better in Michigan poetry contest.” Fort Myers News-Press, 4 Jun 2000.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: