“I’m the Naughty Boy.”

you love science — but probably not nearly as much as Bayard Peakes did

As far as Eileen Fahey was concerned, July 14, 1952 was going to be a great day.

That morning the pretty young woman had practically skipped down Amsterdam Avenue on her way to work. She had a good job, working as a receptionist for the American Physical Society, located in the Pupin Building on the Columbia University campus. She’d had to lie about her age to get it, but it was good work and she enjoyed it.

As she entered the office, she excitedly told her supervisor, Mrs. J.V. Lumley, the good news. Over the weekend Eileen had received three letters from her fiancé, Private First Class Ronald Leo, who was serving on the front lines in Korea. Eileen could not wait to read them. The young woman poured herself a glass of orange juice, took off her wristwatch and crucifix, and opened the first letter.

Eileen was so absorbed by the letter she lost track of what was happening in the office. While her back was turned to the front door, someone walked into the office and asked a strange question: “Do you know, have they dropped the electronic theory yet?”

“I don’t know anything about it,” Eileen responded, then turned to rise and gasped.

A stranger was standing right behind her, brandishing a gun. Eileen raised her hand in self-defense as the gun barked six times. One bullet blew clean through her hand, while the other five slammed into her chest. Stunned, Eileen fell backwards into her chair and said numbly, “It hurts.”

She struggled to rise but only landed face-down on the floor, crumpling the letter she’d been holding beneath her. As her blood oozed out onto the carpet she stared at the stranger, mumbling a description of what was going on: “He’s just standing there. He’s loading the thing again.”

The gunshots were heard throughout the building. Dr. Thomas Green poked his head out of his office to investigate, but when he saw the killer running down the hall, gun in hand, he quickly retreated and locked the door. Mrs Lumley, who was down by the elevator, also heard the shots. As turned towards the sound, the killer ran past. Spotting Lumley, he shouted: “Call an ambulance. I just shot a girl.”

Then he ran down the stairs, and was gone.

Mrs. Lumley ran back to the office to find Eileen lying face-down in a pool of her own blood. Dr. Green arrived moments later and grabbed a phone to call the police. Joseph Sucher, a grad student, arrived on the scene and tried to take Eileen’s pulse. When he couldn’t find one, he held a mirror under her nose to see if she was breathing.

She wasn’t.

Eileen Fahey was dead.

Police were on the scene within minutes, for all the good that did them. The killer was long gone and there was practically no evidence that would help their investigation. They interviewed four witnesses, including Mrs. Lumley and Dr. Green, and used that to craft a description for their all-points bulletin:

Arrest for homicide unidentified white man between 25 and 30, six feet tall, weight 165 pounds, slim build, complexion fair to medium, Irish or Spanish type, dark wavy hair, well-dressed, wearing a blue suit, no hat. This man may be armed with a .22 caliber automatic pistol.

That was all the police had to go on. At first, they suspected that Eileen had been shot by a jilted lover or jealous suitor, but that turned out to be a dead end. Eileen was a good Catholic girl. Ronald Leo had been her high school sweetheart and, as far as they could tell, the only boy she’d ever dated.

Then, they thought it might be revenge. Eileen’s older brother Frank had been shot and killed during a gang war in 1947. The shooter, Alonzo Ramirez, had recently been released from jail. Maybe he was looking for some revenge? The cops brought Ramirez in for questioning, but it was immediately obvious Ramirez wasn’t their man — he was too short, wore spectacles, and, y’know, he wasn’t white. Ramirez was released.

Two of the witnesses said the killer resembled Joseph F. Bent, a fugitive on the FBI’s “10 Most Wanted” list. But Bent’s stomping grounds were in the South, there was no evidence that he’d left them, and he had no motive. It was a long shot at best.

With no leads, the police came to the obvious conclusion: the killer was a madman with no rational motive. Likely a woman-hating he-man, who had targeted Eileen solely because of her gender.

They were partly right.

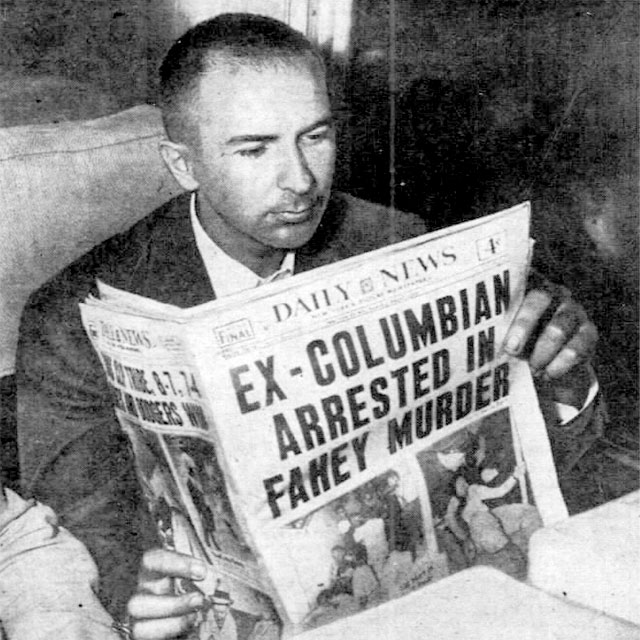

The New York Daily News sent reporters to re-interview witnesses and got a few extra details the police had missed — square jaw, bushy eyebrows, heavy underlip. They had a staff artist whip up a sketch which they plastered all over the city.

That sketch seemed awfully familiar to a Columbia physics professor. He had previously taught at Northeastern University at Boston, and the picture reminded him of a student with unorthodox theories who responded with threats when his thesis was rejected. A quick page through old Northeastern yearbooks gave him a name: Bayard Pftundtner Peakes.

Now the police had something to go on. They called Northeastern, who didn’t know his current whereabouts but knew he was from Maine. Authorities in Maine were more helpful, and gave them Peakes’ current address, a one-room apartment at 36 Fairfield Street in Boston’s Back Bay.

When the police arrived at the apartment, Peakes wasn’t there, but they did find a recently fired Ruger .22 caliber long target pistol which matched the murder weapon. So they waited. Peakes turned up shortly after midnight on July 17th, and was promptly arrested.

Bayard Peakes did not seem surprised. It was almost as if he had been expecting the police. And he seemed… curiously happy.

You got me — I’m the one that killed her. Yes, I’m the naughty boy.

Bayard Pftundtner Peakes

Residents of Peakes’ apartment building and his childhood friends from Maine were shocked. He was a quiet man who kept to himself. He certainly didn’t seem like a murderer. So let’s dig into his history, to see how he got to this point.

Bayard Pftundtner Peakes was born on December 14, 1922 in Dover-Foxcroft, Maine, the youngest of three children. He was a quiet boy who worked hard both at home and in school. He was smart, always interested in science and science fiction. While the other kids were out playing, he’d be at the library poring through physics textbooks.

During World War II broke out Peakes could not wait for the United States to enter the war. He crossed the border and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force to go fight Nazis. He served in England for several years, and was transferred to the US. Army Air Corps when U.S. troops finally arrived in 1944.

Peakes never saw combat, but the war still managed to break him. On March 12, 1945 he was admitted to an Army hospital. He was tense and anxious, suffering from hallucinations and alternating between bouts of paralyzing guilt and violent rage. The Army shrinks gave him a diagnosis of “dementia praecox,” later upgraded to latent schizophrenia with acute psychotic and paranoid manifestations. They prescribed a course of insulin shock treatments, where Peakes was given deliberate overdoses of insulin until he went into a coma, sometimes paired with electroconvulsive therapy.

In September he was discharged back into the care of his parents. At first Barbara Peakes barely recognized her son. Bayard couldn’t speak above a whisper, and still suffered from delusions. Most notably, he didn’t want to eat because he was convinced all the food he was being given was human flesh.

Over the years Peakes would have periodic check-ins with the Veterans Administration to monitor his mental state. He did not want to go, because he was convinced that he would be lobotomized or given another round of insulin shock therapy. He was also afraid of what they would recommend. Psychiatrist after psychiatrist found that Peakes was barely holding it together, still suffering from hallucinations and paranoid delusions, and was unsuitable to enter vocational training programs or attend college.

Peakes needn’t have worried. The psychiatrists’ recommendations were never acted on.

In the fall of 1946, Peakes started attending Northeastern University through the GI Bill. He was such an average student that most of his professors didn’t even remember him. His physics professors, though, oh, they remembered him. He would constantly pester them with his unorthodox theories about electronics — specifically, he was convinced that electrons did not exist. They branded him branded a crackpot, and they did their best to avoid him.

Since his professors would no longer listen to him, Peakes joined the American Physical Society so he could spread his theories. In 1948 he wrote a 13,000 word monograph, So You Love Physics, and submitted it to the APS for publication. It started:

Did you know that the electron never existed? Then read this booklet through and become brilliant.

Needless to say, the APS rejected it. Undaunted, Peakes then used his own money to print 6,500 copies of So You Love Physics at a cost of 8¢ each and sent them to everyone he could think of. He even hand-delivered copies to Boston University, where he gleefully asked a professor what he had to do to submit his paper for a Nobel Prize.

No one responded.

Einstein didn’t answer me. I think he’s crazy.

That didn’t slow Peakes at all. He gave short presentations at multiple APS meetings promoting his theories to disinterested audiences. At least once he was laughed off the stage.

In 1950, Peakes had to drop out of Northeastern. His GI Bill money had run out, and he didn’t have the funds necessary to continue. He took a job in a North End meat-packing plant, where he was nicknamed “Hoppy” because he never stood still. He started suffering from ever-increasing delusions of grandeur. No longer satisfied with merely disproving the existence of electrons, he was now plumbing the secrets of eternal life.

I expect to get someone besides Mr. Filene to help me abolish the electron theory and start a search for a medicine to keep man young…

I still expect to disprove the electron theory, get a political party started, and do some research in medicine. Some day I shall be able to put a few females to work at manual labor, so they might grow some brains. If I don’t find the eternal life, their children will.

In 1951, the Veterans Administration had Peakes declared incompetent and put into the guardianship of his mother. Mrs. Peakes did not seem to realize how serious this was, because she made no real efforts to control her son. In August he left Maine and moved back to Boston, without telling his parents.

He spent the next few months working on a new book, How to Live Forever, which purported to show electronics would extend the human lifespan to 500 years. (Not surprisingly, it did no such thing and Peakes didn’t even address how this was possible if electrons didn’t exist in the first place.) He once again submitted the book to the American Physical Society, and once again it was rejected. This time it came with a letter from the secretary of the society, Karl K. Darrow, gently suggesting that Peakes abandon this line of inquiry because it might ruin his career.

This gentle suggestion threw Peakes into a rage. He decided that if the world would not voluntarily acknowledge his theory, he would do something so heinous that they had to acknowledge his theory. He briefly contemplated blowing up Columbia’s Pupin Physics Laboratory with a homemade bomb, or performing targeted assassinations of prominent physicists and journal editors.

In the end, he decided on a far simpler plan: he would walk into APS headquarters with a gun, and shoot the first person he saw. To that end, he bought a target-shooting pistol at a local store, and jumped on the next train to New York.

On July 13, 1952 Peakes checked into the Kings Crown Hotel, just down the street from the Columbia campus. He went out and had an “educated hamburger” for dinner, caught a movie (Richard Widmark in Red Skies of Montana), had a few beers while reading the evening newspapers, and went to sleep.

In the morning he woke up early and hid his gun in a brown paper parcel held together with scotch tape. He had a quick breakfast and wandered over to the Pupin Building, only to realize he had no idea where the APS offices were. He wandered aimlessly around the lower floors of the building, until a kindly student took pity on him pointed him up to the ninth floor.

On the ninth floor, he ducked into the women’s restroom and unwrapped his gun. He strode into the APS offices, shot Eileen Fahey, and ran down the stairs. Then he leisurely strolled back to his hotel, checked out, and caught the next train back to Boston.

Over the next few days he bought some papers to find out the name of his victim, and started a little scrapbook of newspaper clippings. When the police finally caught him on July 17, he was elated. He had been worried that he wasn’t going to get the publicity he craved, because he’d only killed a girl.

Peakes was all too happy to cooperate with the cops, thinking that his moment of vindication was at hand. He showed not the slightest remorse, and wanted to make sure they knew that Eileen’s death was not his fault. All the blame belonged with the American Physical Society.

It was my book. They wouldn’t even look at my book. They wouldn’t even look at it. What’s the matter with the society? They didn’t even look at it. I know they didn’t look at it. They should have looked at it!

Eager for his day in court, Peakes was surprised when his attorneys plead not guilty by reason of insanity, declaring:

I’m not nuts!

As he was dragged away to Bellevue for psychiatric observation, he kept ranting:

Wait a minute! These fellows in 1949 had dropped the electronics…

Eventually Peakes was found incapable by want of reason to stand for trial, and was committed to the Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane.

Aftermath

Eileen Fahey was buried on July 20. PFC Leo was given emergency leave by the Army to attend the funeral, but didn’t make it back from Korea in time. The Fahey family sued the U.S Army for damages, claiming that officials were negligent since they’d known about Peakes’ precarious mental state for years and had done nothing to make sure he wasn’t a danger to others. The courts ruled against them.

Bayard Peakes was released from the mental hospital in the early 1970s to live with his mother Barbara. When her health started to fail in 1978, he was sent to the Togus VA Medical Center, where he spent the rest of his life. He died on July 1, 2000, having outlived Eileen Fahey by some 48 years. His obituary only mentioned that “he had been away for his family for some years.” I feel like I should have some sympathy for Bayard and his struggles with mental health… but all I can think of is Eileen Fahey bleeding out on the floor.

Ironically, the incident finally got Peakes’ writing the attention he craved as physicists across the country finally cracked open the copies of So You Love Physics that they’d been sent. Unfortunately for Peakes, once you started reading the pamphlet it was immediately obvious that it presented no coherent theory. It was the pseudo-scientific ravings of a madman with a poor grasp of elementary atomic physics.

The American Physical Society had long been conflicted about what to do about fringe pseudo-scientists like Peakes. One group argued that these individuals should be put on a list of “eccentrics” who could be denied the right to speak at APS meetings.

Another group objected, arguing that being deplatformed is exactly what caused Peakes to snap. By allowing the crackpots to speak you could keep an eye on the fringe cases, give them an outlet for their frustrations and prevent them from becoming dangerous. Besides, the free exchange of ideas lies at the very foundation of what it means to be both an American and a scientist. And hey, you never know, today’s crazy theory might turn out to be tomorrow’s paradigm-shifting discovery. Stranger things have happened.

In the end, the free speech faction won out. Today, any dues-paying APS member can give a ten minute presentation at a special session of the APS’s national meeting, as long as they meet the same submission criteria as every other presentation. The audience is often filled with folks who are just there for a good laugh. But there is an audience, and there hasn’t been a repeat of the Fahey shooting in the last 68 years.

The free speech wing was led by physicist Luis Walter Alvarez. He may have had personal motivations to advocate for the policy, because he had some fringe ideas of his own. If you can believe it, he actually thought that the impact of a giant asteroid was responsible for wiping out the dinosaurs.

What a crackpot.

Connections

The story of Bayard Peakes is prominently featured in Martin Gardner’s seminal Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. You know who else is prominently featured in Fads and Fallacies? Hollow Earth theorist Dr. Cyrus Reed Teed (“We Live Inside”), chromotherapist Dr. Dinshah Ghadiali (“Normalating”). flat-Earth prophet Wilbur Glenn Voliva (“Marching to Shibboleth”), and science fiction author Richard Sharpe Shaver (“A Warning to Future Man”).

Peakes’ hometown of Dover-Foxcroft was also home to a large Spiritualist camp (“A Good Thing to Die By”).

Sources

- Gardner, Martin. Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. New York: Dover, 1952.

- “Luis Walter Alvarez.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_Walter_Alvarez Accessed 5/10/2020.

- Kivel, Martin and Kline, Sid. “Comb city for slayer of steno at Columbia.” New York Daily News, 17 Jul 1952.

- Kivel, Martin and Kline, Sid. “Cops believe madman was slayer of steno.” New York Daily News, 16 Jul 1952.

- “Ex-Columbian held; claim he admits killing.” New York Daily News, 17 Jul 1952.

- Kivel, Martin and Lee, Henry. “Steno slayer planned more fatal revenge.” New York Daily News, 18 Jul 1952.

- Kivel, Martin and Lee, Henry. “‘I am not nuts!’ steno’s killer cries as he’s led to Bellevue.” New York Daily News, 19 Jul 1952.

- “3,000 give neighborly good-by to slain steno.” New York Daily News 20 July 1952.

- Abelli, Alfred. “Kin of crazed killer’s victim to sue U.S.” New York Daily News, 6 Aug 1952.

- Schreiner, S.A. “Can you spot a mad killer?” Parade, 7 Sep 1952.

- Dressler, David. “We set them free to kill.” American Weekly, 5 Oct 1952.

- Fahey v. United States, 153 F. Supp. 878 (S.D.N.Y. 1957)

- Lustic, Harry. “To Advance and Diffuse the Knowledge of Physics.” American Journal of Physics, 68(7):595-636, July 2000.

- “Obituaries: Bayard Pfuntner Peakes.” The Daily ME. http://www.thedailyme.com/Obituaries/bayard_pfuntner_peakes.html Accessed 5/10/2020.

- “Why no paper should ever be rejected.” The Geomblog, 18 Apr 2005. http://blog.geomblog.org/2005/04/why-no-paper-should-ever-be-rejected.html Accessed 5/11/2020.

- Spyra, Jen. “Murder, she wrote: unlocked tales from the Columbia crypt.” Columbia Specatator, 26 October 2006. http://spectatorarchive.library.columbia.edu/?a=d&d=cs20061026-03.2.9&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——- Accessed 5/10/2020.

- Palmer, Jason. “‘Crackpot’ science and hidden genius at physics meeting.” BBC News, 18 Apr 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-22171039 Accessed 5/9/2020.

- Scoles, Sarah. “A Murder at the American Physical Society.” The Atlantic, 29 Sep 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2015/09/american-physical-society-murder/407650/ Accessed 5/10/2020.

Links

- American Physical Society

- The Constant: Crackpots (another great take on this whole mess)

- Sarah Scoles

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: