Independent by Accident

a brief history of Neutral Moresnet (1814-1918)

An ambitious Prince

William Frederick, prince of Orange-Nassau, was an ambitious man. The House of Orange had been chased from Holland by French revolutionaries, so when the Napoleonic empire crumbled in the final months of 1813 he was determined to grab as much of the spoils as he possibly could. His ultimate ambition was to create a kingdom for himself. He succeeded in being accepted as the sovereign prince of the former Dutch republic, but he had grander plans.

British foreign policy presented him an opportunity. Britain wanted to strengthen the Dutch state in order to provide a barrier to France and keep the North Sea Ports of Antwerp and Ostend out of the hands of any rival. William was all for it, but he pointed out that to do so effectively, this new kingdom of the Low Countries would have to be large enough. It would have to include the former Habsburg territories of the Southern Netherlands. He also suggested adding a stretch of the Rhineland, perhaps the entire left bank of the Rhine up to the Moselle. This would place his border conveniently close to his ancestral German possessions of Nassau, and make the new Kingdom of the Netherlands a wine producing country.

His claims on the Rhineland raised eyebrows in Berlin. Prussia had its own ideas about blocking any future French expansion, and these involved uniting the various Rhineland territories under Prussian rule in a new Rhine province. They also planned on annexing the Eastern half of the former Habsburg territories, so that the Western border of the new province would be the Meuse.

With both states claiming a sizable chunk of the Rhineland, it took pressure from the other great powers to sort things out at the Congress of Vienna. Eventually a compromise was reached which created the United Kingdom of the Netherlands, comprising modern day Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg.

When the time came to stake out the new Dutch/Prussian border, there was a tension in the air. At the time, staking out a border meant exactly that: sending surveyors to put physical markers in the ground. This was no easy task, given the state of cartography. Detailed maps were rare, and when maps were detailed they only had a superficial similarity with the situation on the ground. Surveying parties from both states met at the southernmost point where the old border still stood and then worked their way south, defining the new border, carefully watching each other for signs of sharp practice.

Things went well until they reached the village of Kelmis. The descriptions of the border in the Treaty of Paris made no sense, and would have put the eastern border of the Netherlands several kilometers to the east of the western border of Prussia, which was obviously impossible. The special problem was that here they weren’t dealing with farmlands and forests. Here was a real prize: the zinc mine of Vieille Montagne.

Vieille Montagne

The existence of zinc had already been known since ancient times, but separating the metal from ore had proved difficult, so its uses had remained limited. But in the early, 1800s Jean-Jacques Dony from Liège had perfected an extraction method far more efficient than anything that had come before. He had obtained a mining concession in Kelmis from Napoleon to put it into practice. To sweeten the deal, Dony presented a zinc bathtub to the Emperor, who took it everywhere on his campaigns. Now Dony could produce zinc in really industrial quantities, and he had access to one of richest deposits known at the time.

The main advantage of zinc is that it doesn’t rust. Not only could it be used to make various waterproof objects, such as baths or water pipes, it could also be applied as a protective coating to steel, or mixed with copper to produce brass. The potential was enormous, and here in Kelmis was the only firm in Europe that could take advantage of it.

The representatives of both kingdoms squabbled over who should own Kelmis. The only thing they could agree on was that each was determined not to let the other party have the mine. In the end, they decided to leave the border undefined in that area, to be settled at a later date.

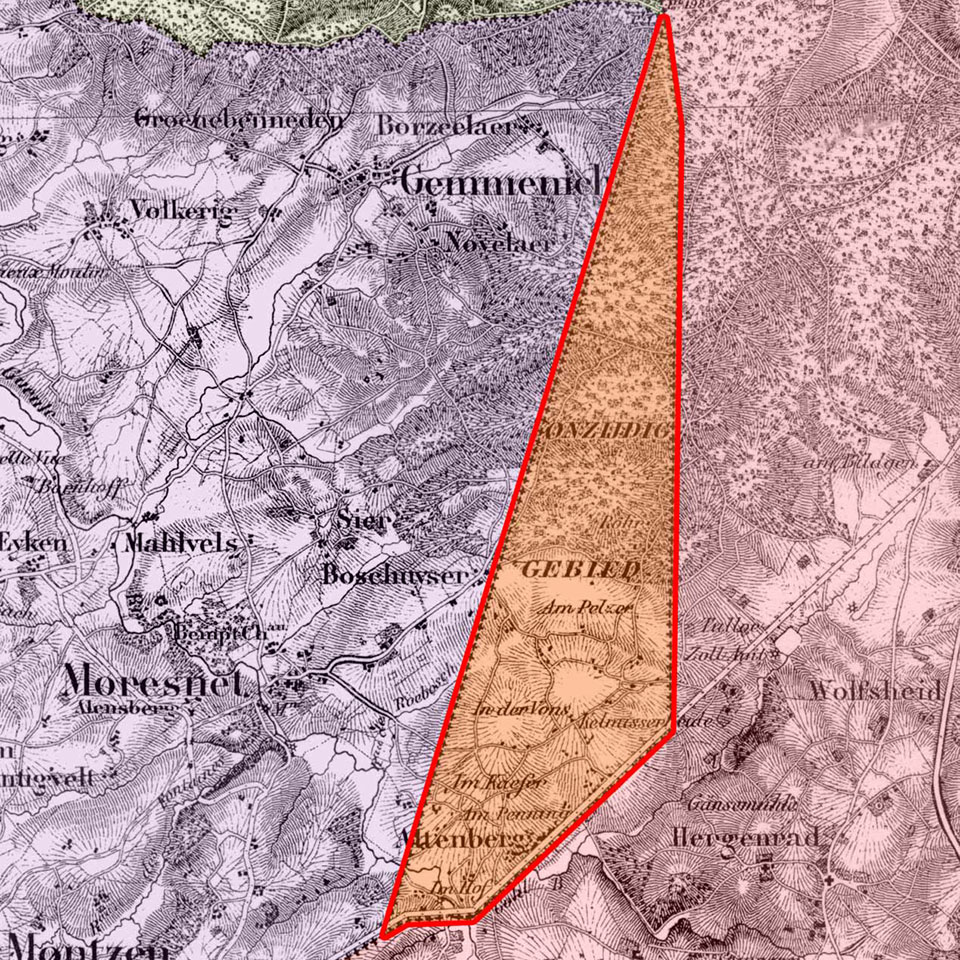

In this way a neutral zone was created in the rough shape of an isosceles triangle, with the Liège-Aachen highway as its base, and then two straight lines meeting in Vaals in the north. It contained the mine and the neighboring village of Kelmis, an area of about 3.5 square km (1,4 square miles) with a population of 256 people. Until the dispute was resolved, the territory was to be administered jointly by the Netherlands and Prussia, who (most importantly) would also share the taxes on the proceeds of the mine.

And so the territory of Neutral Moresnet was created. How big the muddle was, is already obvious from the name. Although the territory was called Moresnet, there were actually two villages of that name: one on the Dutch side of the border and one on the Prussian, and neither was in the territory of Neutral Moresnet, which only contained the village of Kelmis.

A Neutral Zone

Any hope that the problem of Neutral Moresenet would be resolved soon would require cooperation and compromise from both parties, but king William I of the Netherlands (as prince William Frederick had now become) was nothing if not obstinate. Some solution would have to be found for administrating the neutral zone. Both parties were reluctant to create a special regime, since that could be seen as weakening their claim that Moresnet was an integral part of their kingdom. Introducing either Dutch or Prussian law was out of the question. However, the system of joint administration by two officials that was in place made even the most routine official act a matter of international diplomacy.

Then a Prussian official had a bright idea. The area could be considered part of the Napoleonic empire that hadn’t been allocated yet, so why not revert to the Code Napoléon? An additional advantage was that everyone concerned was familiar with the Code, as the whole area had formed part of the Napoleonic Empire until a few years before. So in 1822 the Code Napoléon was officially reintroduced, resurrecting the Napoleonic Empire in a small sliver of land. The great man himself had died in 1821, so we don’t know what he would have thought of it.

There was also was the question of taxation. Apart from the mine, whose proceeds were covered in the original settlement, there was nothing worth taxing. Both states agreed that they weren’t going to open another can of worms, and decided to waive any taxes. Similarly, residents were exempt from military service. In this way, while the modern nation state took form all around Europe, a small libertarian enclave was created.

For those who are wondering where the local population stood on this, the short answer is, “nobody asked them.” At the time, subjects were supposed to do as their kings told them, and not get any funny ideas. Besides, as any diplomat would have told you, the matter was already complicated enough as it was without asking the opinion of a few cowherds and miners.

William’s obstinacy not only prevented a lasting solution to the Moresnet problem, it also soured relations with his new subjects in the Southern Netherlands. Tensions mounted and in 1830 revolution broke out in Brussels, ending the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and creating the modern states of Belgium and Luxembourg. Neutral Moresnet now bordered Belgium, so the new state now took over the role of the former United Kingdom.

The smallest state in the world

Thus the ‘smallest state in the world’ was created. It was very tiny, roughly the size of present day Monaco, and absolutely dwarfed by, say, Andorra or San Marino. Before you ask, Vatican City is smaller, but that was only created in 1929, and until 1870 the Pope still ruled a sizable chunk of Central Italy. It would also be a bit of an overstatement to call Neutral Moresnet a ‘state’. Both Belgium and Prussia went to considerable lengths to maintain the fiction that this was just another village, like any other in their kingdoms, in order to support their claims to the territory.

As an example, since Kelmis had formed part of Neu-Moresnet, which now was Prussian, the mayor of that village continued to conduct all official business. There were separate forms for Prussian citizens and ‘neutrals’ as they were called. The town hall was on the Prussian side of the main road, which meant that the citizens of Kelmis technically had to cross into a foreign territory each time they needed an official document.

Attempts to settle the issue went nowhere. The main stumbling block was financial. As it was, the taxes on the mine were split between Belgium and Prussia, so whichever country ended up with Vieille Montagne would have had to compensate the other for the loss of revenue. Predictably, it proved impossible to agree on the future value of the mine. There was some hope that the problem would solve itself when the mine became unprofitable, forcing Vieille Montagne to shut down or move its operations. Then Prussia would get the village and Belgium the forested parts.

Both states seriously underestimated the business acumen of the management of Vieille Montagne. In the 1850s, it was run by the couple Charles Le Hon and Fanny Mosselman. Charles Le Hon was the Belgian ambassador to France. Fanny Mosselman was also the mistress of the Duc de Morny, the illegitimate half brother of Napoleon III and the financial right hand man of the Emperor. His greed and corruption were legendary; in the Paris of the 1850s, if your financial scandal didn’t involve the Duc de Morny, it really wasn’t worth bothering the press about. This was also the time when Haussmann was radically reshaping the architecture of Paris, introducing, among other things, the iconic mansarde roofs, clad with zinc. Zinc which Vielle Montagne was happy to provide.

The ménage à trois between Morny, Fanny Mosselman and Charles Le Hon proved to be very profitable. Together they put Vieille Montagne on a firm financial basis and used their political clout to have the concession for the mine, which was set to expire in 1856, prolonged in perpetuity. This was only the start of their success story. Vieille Montagne gradually shifted from mining to treating ore from other mines. The firm also followed a policy of aggressive expansion, taking over potential rivals. In the second half of the 19th century, Vielle Montagne was one of the leading players in zinc with operations throughout Europe and the Americas.

Kelmis and the Law

The peculiar nature of Neutral Moresnet made it something like a real-life 19th century equivalent of Cloud City and similar ‘free zones’ that pop up in SF. It was run by Vieille Montagne and the company was mainly interested in producing zinc and making money. There was just one constable in Kelmis, and he was paid by the company, so his main duty was to protect the interests of the mine. Upholding the general rule of law was a distant second.

This is not to say that there was no rule of law at all. For most administrative matters, Kelmis depended on Prussian Moresnet. The Prussian police were allowed to cross the highway and intervene, but that only could happen within well-defined limits agreed upon by Belgium and Prussia. If, say the Prussian police wanted to apprehend a fugitive sheltering in Kelmis, they first had to have the permission of the Belgian commissioner in Verviers before they could do anything. Given the speed of 19th century administration, this gave any fugitive ample time to plan an escape. Anyone wishing to evade Prussian or Belgian law could do so reasonably safely, as long they didn’t attract too much attention.

The best example of Moresnet’s relative lawlessness is gambling. When countries in Europe started to crack down on gambling in the late 19th century, gamblers started to look out for alternative places to ply their trade. Neutral Moresnet seemed ideal. It was still governed by the Code Napoléon, and while the Emperor had given attention to many things he was completely silent on the subject of gambling.

Inspired by the success of Monaco, in 1903 former casino owners converted the local hotel into a casino (thinly disguised as a gentleman’s club) in order to transform Neutral Moresnet into the Monte Carlo of the Ardennes. Neither Prussian nor Belgian authorities were going to stand for that. Officials scoured the texts of Napoleonic law and found that the casino could be considered as an illegal gathering. Armed with this decision, they intervened and the casino had to be closed after only two weeks’ operation. This didn’t end gambling in Kelmis, however. It just had to operate on a small scale and behind closed doors.

The apparent lack of a rule of law inspired a romantic views of the territory. Throughout the 19th Century, foreign journalists drifted to Kelmis to report on the curious state of affairs. Their articles tend to present it as a remnant of a simpler time, free from the cares of the modern world, not to mention taxes. As the Hampshire Telegraph put it in 1906:

A peculiar thing about Moresnet is the stability of its expenditure. It is said that the budget of the country has amounted to be exactly 3,735 francs every year for ninety years past. There are no Army and Navy estimates, the bogies of great countries.

The fortunate people of Moresnet have not been troubled by wars or rumours of wars, and have long been exempt from Military service.The country has escaped many of the perils which beset more pretentious jurisdictions, but it has been denied one of the dearest rights of sovereignty. It must use the postage-stamps of Prussia or Belgium.

Amikejo

Except for the part of the postage stamps, nothing in the article is accurate. One fundamental error stands out Neutral Moresnet wasn’t, strictly speaking, a sovereign state. For one thing, there was no tradition of sovereignty, unlike, say Monaco, and the inhabitants had never been independent before 1815. Power was firmly held by Prussia and Belgium, and it was only the impossibility of both countries to agree that allowed Kelmis some wiggle room.

As time went on, a certain sense of identity did develop in the territory. This was personified by Dr. Wilhelm Molly. He started out as company doctor of Vieille Montagne in Kelmis, and would become one of the leading proponents of the independence movement for Neutral Moresnet. An avid stamp collector, his first feat of arms was the introduction of postal stamps for Neutral Moresnet, which were issued from the local post office. These had no legal basis, and amounted to a declaration of independence, at least in postal matters. The Belgian and Prussian authorities would have none of it. The local post office was closed and the stamps were declared illegal, based on a law of 1711.

Wilhelm Molly was more successful in his next project: making Esperanto the official language of Neutral Moresnet. Esperanto had been created in 1887 by L.L. Zamenhof as an artificial language for international communication. This caught the imagination of Wilhelm Molly and he started to dream of Neutral Moresnet as the centre and birthplace of a worldwide Esperantist movement. What better place for a neutral language than a neutral zone, sandwiched between three languages: Dutch, French and German? He managed to obtain the support of Zamenhof himself and convinced the 4th International Esperantist Congress in Dresden in 1908 to move the headquarters of the organization to Kelmis. Language courses were organized in the village, quickly making Neutral Moresnet the area with the most Esperanto speakers per capita (not a particularly high bar to clear, it must be said). Activities were held, a national anthem was composed and Moresnet was renamed Amikejo, place of friendship in Esperanto. The real impact of all this remained minimal, however and in 1914 everything was swept away by the Great War.

The end

In the beginning of the 20th Century, there was increasing pressure from newly unified Germany to settle the issue of Neutral Moresnet once and for all. Times had changed. There were all kinds of illegal activities going on in Kelmis: gambling, prostitution, smuggling. It was a place where unmarried pregnant women could go to have their babies, without leaving an embarrassing paper trail behind them. In earlier times, this sort of lawlessness was seen as the cost of doing business, necessary to preserve the income of the mine. With the relative importance of Vieille Montagne declining and mining activity finally winding down, there was no place for such an anomaly in the high-minded Germany of the time. Besides, it was the age of nationalism, and it was felt that the honest German citizens there could no longer languish under a mercantile and backwards regime. Top level meetings were held and various plans to dividing the zone with Belgium were proposed.

Vieille Montagne, however, found it highly convenient to have a little neutral zone of its own, if only because it protected them from the labour laws that were being introduced in other countries. Neutral Moresnet was still governed by Napoleonic law, and that didn’t mention trade unions. The firm was well connected in Belgian political circles and used its influence to stonewall any attempt at abolishing the zone. Also, nationalism worked both ways. In the early 1900s Belgium had become deeply suspicious of its powerful neighbor. Giving up even part of the zone could be construed as bowing to German expansionism and surrendering honest Belgian citizens to an authoritarian and militaristic regime.

Then there were the inhabitants themselves. They had become rather proud of their peculiar (and largely tax free) status. German insistence only strengthened their sense of identity. By now democracy had firmly taken hold in Europe, so any solution would have had to include a referendum of sorts. It was true that many Germans were living in Kelmis, but a good deal of them had moved there to escape taxes. They were less than keen that the German Empire would be catching up with them.

This all became moot in August 1914, when the German Army rolled through Kelmis on their way to Paris. The area was annexed/reunited with the Vaterland and that was that, until 1918. At the peace conference in Versailles the Belgian delegation was adamant that the country ought to get reparation for the invasion and occupation, and made many and various territorial demands (mostly toward the Netherlands). The only one that stuck in Europe was an area along the Belgo-German border with a mixed German- and French-speaking population. People who are familiar with the Battle of the Bulge might recognize the names of some these places, such as Malmédy or Sankt Vith. In a scaled down parallel to the restitution of Alsace-Lorraine to the French, these were allotted to Belgium. As the Kingdom of Prussia was in no position to object, Neutral Moresnet was added to Belgium as well.

And so a hundred years of neutrality came to an unceremonious end.

There’s not much left to of Neutral Moresnet these days. In Kelmis itself, there is a museum about the zinc industry and the Neutral Zone. At the point where the four borders of Neutral Moresnet, Belgium, The Netherlands and Germany used to meet, there are some signs in Esperanto.

Other than that, Kelmis has become a village like any other.

Connections

Other dreamers who were into Esperanto include librarian Paul Otlet, who designed an analogue system to sort and retrieve all of the world’s information (“Steampunk Google and the World City”).

Sources

- Dröge, Philip. Moresnet, opkomst en ondergang van een vergeten buurlandje. Utrecht: Uitgeverij Unieboek, 2016.

- Uitterhoeve, Wilfried. ‘Een innige vereeniging’ Naar één Koninkrijk van Nederland en België in 1815. Nijmegen, Uitgeverij Vantilt, 2015.

Links

- Amikejo (Dutch with Esperanto Subtitles)

- Museum Vielle Montagne

- The Tim Traveler: Vaalserberg: Holland’s Highest Mountain (& The Strange Story Of Neutral Moresnet)

- The Tim Traveler: How Germany Gave Belgium Its Highest Mountain (And Then Tried To Get It Back)

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: