Steampunk Google and the World City

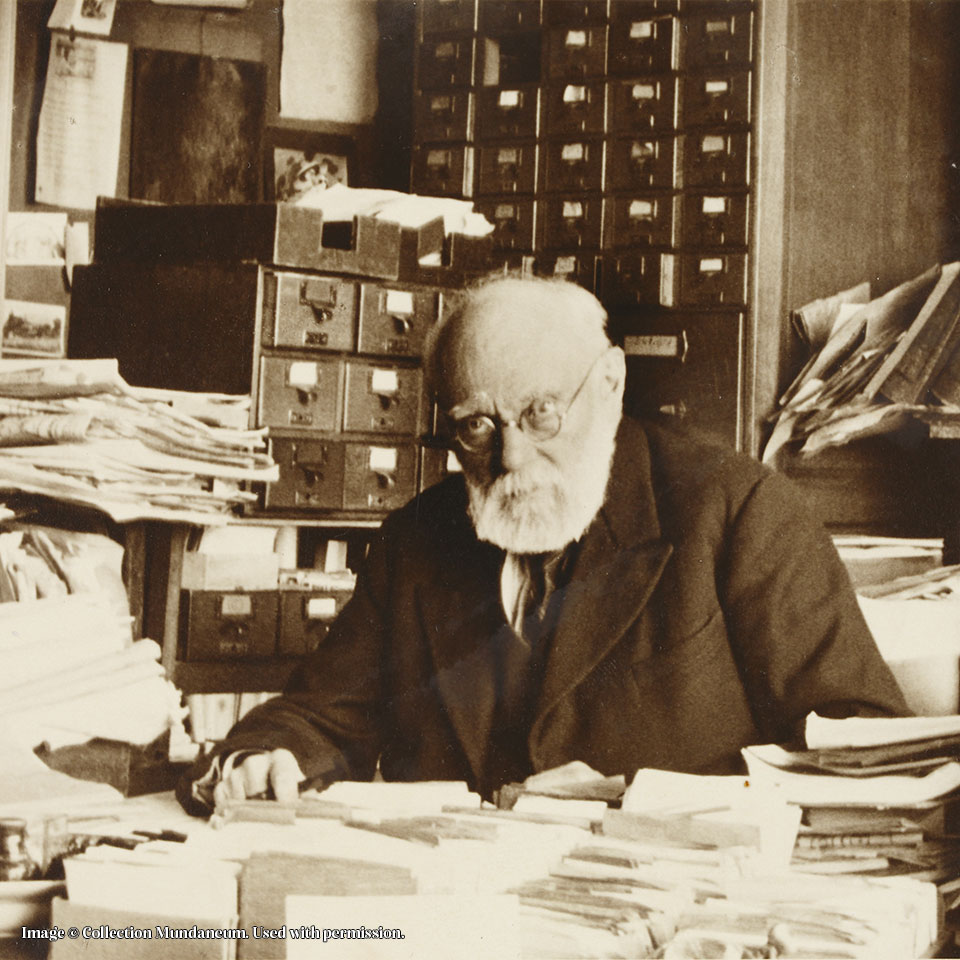

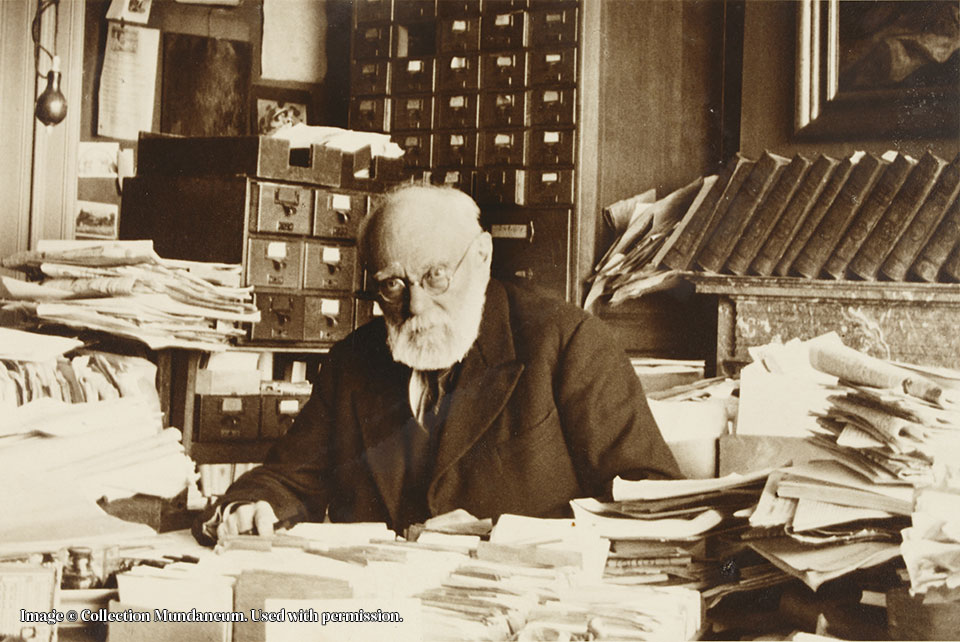

Paul Otlet and the Mundaneum

If you were a believer in scientific progress, the early Twentieth Century was a wonderful time to be alive.

Great strides were being made in science and technology, explorers were mapping the last unknown places on Earth, steam ships and trains were crisscrossing the globe, cures were being discovered for diseases that had decimated previous generations. The future promised so much more: radio and telephone had already revolutionised communications, the invention of sound recording and moving images opened up exciting possibilities, and powered flight was about to change transportation forever.

This explosion of knowledge created a new set of problems. Books and magazines were being published at ever increasing rates, making it impossible to keep track of every new development. The difficulties of organising and dispersing information threatened to stop the future dead in its tracks. Information technology needed the kind of increase in speed and efficiency that was being realised for ships and trains.

This problem was of particular concern to a young Belgian lawyer named Paul Otlet. He was born in 1868 into a family of successful businessmen and studied law with the intent of entering the family business (real estate development and trams). But Paul was a dreamer. He firmly believed that science and cooperation would soon solve humanity’s problems, and that a free and efficient flow of information was the key to that progress.

International Bibliography

Otlet’s life took a decisive new turn when he met Henri Lafontaine and his sister Léonie in the early 1890s. The Lafontaines were a decade or so older than Otlet and were prominent figures in various progressive social movements. They transformed Otlet’s outlook on life, turning him from a rather unremarkable lawyer into an energetic activist for a better world.

The late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries were the heyday of nationalism and racism, dominated by harsh ideologies like social Darwinism which saw the struggle for survival as the basis of all existence, making war and competition the way to progress.

Yet there was a countercurrent which took a completely different view of human development. It saw the march of history as one towards greater and wider cooperation, from the early isolated tribes towards a world-wide civilisation. With the modern revolution in communication technology, it would finally become feasible to unite all of mankind in one world family. Philosophical and spiritual branches of this movement took inspiration from Freemasonry and Theosophy, and tried to find the universal principles underlying all religions. This idea of a world community also inspired Ludwik Zamenhof to come up with Esperanto, the language of hope. Henri and Léonie Lafontaine were active in these internationalist circles, promoting, among other things, pacifism, disarmament, international solidarity, social progress, and women’s rights. Henri was a prominent member of the Belgian Socialist Party and held a seat in the Senate. His efforts to improve international cooperation and resolve conflicts through arbitration earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1913.

Paul Otlet and Henri Lafontaine met while working together on a bibliography of Belgian jurisprudence. Realising the crucial role of reference works and bibliographies in spreading knowledge and enabling progress, they started compiling an international bibliography of law and sociology. But as they worked, they asked themselves, why stop at law and sociology? Why not unite all of science with one great universal bibliography? Why not make all the knowledge in the world accessible to everyone?

The project established a pattern that would repeat itself across Otlet’s career. It started off as a limited, well-defined idea, that might even be feasible; it gained momentum; and finally blossomed into a vision of epic proportions.

The two created the Office International de Bibliographie (International Office of Bibliography) in 1894. The idea was that it would be a truly universal index which encompassed all subjects and all publications in the civilised world. It was an ambitious idea, but not beyond the realm of possibility. After all, the entire book production of the Nineteenth Century in the Western World has been estimated at just 8 million titles all told.

The founding conference of the OIB was very encouraging, and the next step was to obtain royal patronage. Otlet and Lafontaine approached King Leopold II (of Congo infamy) to give the organisation official status. The king liked the idea, as it would increase Belgium’s standing as an international hub in Europe. At the time, Belgium was the seat of numerous international organisations, for the same reasons that would later lead the European Communities to choose Brussels as their seat: it had good infrastructure; was convenient to reach from Germany, Great Britain, or France; and above all, Belgium presented no political threat to anyone. Of the roughly 109 international organisations that existed in 1909, 17 had no fixed seat, 15 were in Switzerland, 2 in Holland, and a whopping 42 were in Belgium. Leopold II was eager to support anything that would increase the international standing of Belgium. At the end of the 1890s, Brussels was hosting more international events than Paris, twice as many as London, and ten times as many as Berlin. Something like the OIB was straight up Leopold’s street.

In 1895 the Office International de Bibliographie was officially recognised by Royal Decree as a semi-public institution. The royal approval and funding allowed Otlet and Lafontaine to set up offices and to engage staff. Judging by photographs, these were mainly young women. Both men worked tirelessly to promote their idea internationally, such as presenting the OIB at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1900, where they secured a spot at the Grand Palais attracted many interested visitors, and even won a gold medal.

Here we need to make a quick aside. Lafontaine and Otlet had a persistent habit of creating new organisations or modifying existing ones whenever it took their fancy. Parallel to the OIB, which was linked to the Belgian state, they also created the Institut International de Bibliographie (IIB), which was wholly private, and this would in turn blossom into the Répertoire Bibliographique Universel, Bibliothèque International, and Archives Documentaires, not to mention adjacent non-bibliographical institutions such as the Office Central des Associations Internationales, later the Union des Associations Internationales,-It is not always clear whether Otlet himself knew which organization was which, if only because he often used their names interchangeably. I’ll try to keep the terminology as simple as possible.

Going decimal

To build a universal bibliography, you need a universal classification of subjects. Otlet and Lafontaine based theirs on the existing system of Melvil Dewey. He had developed a decimal system, with nine top level classes, which were then subdivided in ten divisions each, which could then be further subdivided and so on and so forth. This had become the de facto standard for public libraries in the United States. Dewey found in Otlet a kindred spirit, which would lead to a lifelong friendship and collaboration between the two men.

Otlet made two great changes to Dewey’s system. One concerned the division of subjects into classes. Dewey had designed his system first and foremost as a tool for cataloguing public libraries in the United States. Practicality was more important than theoretical perfection, which in effect meant that, the more books American libraries held on a particular subject, the higher up that subject moved in the classification. This resulted in a very America-centric system. Dewey was well aware of this and freely admitted: “theoretically, the division of every subject into just nine heads is absurd, practically, it is desirable.” (A Classification and Subject Index – Gutenberg). To achieve a true universal classification, Otlet rearranged the classes slightly, notably merging literature and linguistics under number 8.

More importantly, Otlet and Lafontaine introduced grammar. Instead of creating a new set of subdivisions for each new heading, they created a set of common denominators which could be used to modify a heading, governed by rules of interpunction. For instance (4) would be Europe, with (44) France, (493) Belgium and so forth. So 94 (4) would be the history of Europe and 94 (493) the history of Belgium, whereas 72 (4) would be architecture in Europe and 72 (493) architecture in Belgium. The advantage of this is that subclasses have the same number throughout the system. Further operators could describe periods, the type of document, the language it was written in, and so on. In this way, a symbolic language was created, in which most subjects could be classified with a relatively limited set of terms.

The new classification was known as the Universal Decimal Classification (UDC) and is still used in libraries and institutions all over the world. Otlet hoped for a convergence of the UDC and Dewey’s system, but it never happened. Dewey opposed the UDC on the grounds that the rules for interpunction, which used brackets, colons, and the like, complicated matters for librarians and could be confusing for users. (He certainly was right on the last point. In my undergraduate days it took me some semesters before I realised that, say 82.03 was not the same as 82:03, and that both were different from 82 (03).)

18 million index cards

The heart of the OIB (or IIB) was the card index: the Répertoire Bibliographique Universel (RBU) – the Universal Bibliographic Repertory. Otlet recognised the futility of creating a static printed bibliography which would be out of date before it reached the shelves. Only a dynamic card index could capture the speed of the development of knowledge. Otlet saw the RBU as a service which would provide bibliographies on demand, either as a subscription or upon request. For a fee, the client could ask about a subject and would then receive copies of the corresponding index cards.

This never took off, because of the technical limitations of reproducing index cards at the time. Otlet and Lafontaine did offer a prize of 500 francs for anyone who could come up with a machine that could reproduce index cards in large numbers, but nothing ever came of it. As a result, whenever the RBU received a request a staff member would have to consult the card catalogue and copy out the necessary cards by hand. The first search engine of modern times was a girl scurrying among endless banks of filing cabinets.

Work progressed steadily. In 1905 the RBU held 7 million index cards, a total that would exceed 10 million in 1912 and eventually reach an estimated 18 million in 1934, when disaster overtook the organisation. (But more on that later.)

Towards the Mundaneum

The year 1910 was a turning point in the development of Otlet’s project. In that year a Universal Exposition was held in Brussels, where Otlet met Patrick Geddes, and was taken with his concept of the museum as a tool for disseminating knowledge and creating understanding. The concept of Geddes’s “Thinking Machines”, diagrams of complex ideas that relied on visual logic instead of linear narrative explanation, meshed completely with Otlet’s ideal of representing information visually. The two made plans to collaborate, like opening a branch of the IIB in Scotland, which came to nothing.

However, Otlet was now determined to give his project a new dimension. Instead of merely listing and cataloguing all knowledge, it would also have concrete form as a museum, and so the Musée Mondial was born, as part of the Union des Associations Internationales (UIA). The museum’s collection consisted originally of material left over from the International Exhibition of 1910 (no doubt the exhibitors were happy that they didn’t have to dispose of it themselves). Added to this were the collections of the IIB, which included a library, and of course the endless filing cabinets of the RBU.

Space for the museum was found in the Palais du Cinquantenaire, where the IIB had already set up offices. The Cinquantenaire was one of Leopold II’s grand projects, built to commemorate Belgium’s fiftieth anniversary in 1880. It consists of a grandiose set of buildings, including two vast halls, the whole linked by a triumphal arch. If you ever visit Brussels on a clear day, it is well worth going up the triumphal arch to enjoy a panoramic view of the city.

The original idea was that the Cinquantenaire would eventually house the nation’s prestigious museums of art and antiquities, but by the early 1910s, the Belgian government was still looking for occupants. The Musée Mondial looked like a promising opportunity and Otlet was allowed to make use of part of the South Wing of the complex. The extent of the Musée Mondial (renamed Palais Mondial in 1920) quickly mushroomed to 60 rooms and 20.000 exhibits by the late 1920s.

The concept behind the Musée Mondial was that it was a permanent version of the great universal exhibitions of the turn of the century. There were national and international sections, which would be maintained by the individual countries for the national sections, or by specialised international organisations for the thematic ones. The grand purpose behind it all was to educate the public and promote international understanding through learning about the cultures of the world. In addition to this, talks and conferences about social and scientific questions were regularly held. To finance all this, the UIA approached the Carnegie Foundation, which responded favourably. In 1913 Andrew Carnegie even visited the Musée Mondial himself.

World City

Otlet’s imagination soared higher. No longer content with a mere museum in Brussels, he envisaged a true city of knowledge, the intellectual capital of the world, with the museum concentrating the knowledge of Mankind at its heart. This eventually would be known as the Mundaneum.

This project took flight when Otlet met another utopian dreamer. Hendrik Christian Andersen was a Norwegian born American sculptor, who had moved to Rome at the end of the Nineteenth Century. There he struck up an intimate friendship with Henry James, with whom he kept up a regular correspondence. Andersen had a taste for the monumental, and from 1902 started dreaming of designing a World City as a spiritual beacon for mankind. In 1907 he contacted the Parisian architect Ernest Hébrard and together they produced a massive two volume book of designs. The city would promote a new form of social interaction through its layout and architecture, in the spirit the Paris Expo of 1900. This in turn would free the inhabitants from their baser instincts and inspire them to lead better lives, which would in time end all the evils of society.

To find sponsors and promote the project internationally, Andersen hired the services of Urbain Ledoux, who was active in the peace movement and was internationally well connected. His first task was to convince the governments of the world to make the World City a reality. Ledoux knew Lafontaine through the international peace movement and so got into contact with Otlet. Years later, after falling out with Hendrik Andersen, Ledoux would convert to Baha’ism (or Buddhism, accounts vary), call himself Mr. Zero and stage social protests to help the homeless in New York in the 1920s.

Otlet immediately saw the potential of incorporating his vision of the Mundaneum into the proposed World City,and showed Ledoux a site near Brussels which he hoped the Belgian government would purchase for the project. For funding they already had the backing of Andrew Carnegie, and Otlet was convinced he would also be able to use the trust fund of the recently deceased King Leopold II, which contained the fortune the king had gathered by exploiting the Congo. Andersen’s widowed sister-in-law, who was his partner in the whole enterprise, was positively appalled by the idea of financing the World City with blood money from Leopold II. She needn’t have worried; Leopold II had made his inheritance a complicated affair, partly to obscure his questionable finances and partly to spite his family. Powerful parties were already fighting each other for their piece of the pie, including Leopold II’s young widow, the rest of the royal family, and the Belgian state. The idea that Otlet and Lafontaine would ever get access to any of this money was perhaps the most optimistic aspect of the whole idea.

Andersen began to work with the Belgians to merge the two projects and wrote excitedly of his plans to Henry James only to receive a withering reply.

Brace yourself. Your mania for the colossal, the swelling & the huge, the monotonously & repeatedly huge, breaks the heart of me for you… The idea, my dear old Friend, fills me with mere pitying Dismay, the unutterable Waste of it all makes me retire into my room & lock the door to howl! Think of me as doing so, as howling for hours on end, & as not coming out till I hear from you that you have just gone straight out on the Ripetta & chucked the total mass of your Paraphernalia, planned to that end, bravely over the parapet & well into the Tiber. As if, beloved boy, any use on all the mad earth can be found for a ready-made city, made-while-one-waits, as they say & which is the more preposterous & the more delirious, the more elaborate & the more “complete” & the more magnificent you have made it. Cities are living organisms, they grow from within & by experience & piece by piece; they are not bought all hanging together, in any inspiring studio anywhere whatsoever, and to attempt to plank one down on its area prepared, as even just merely projected, for us is to – well it’s to go forth into the deadly Desert and talk to the winds.

(Henry James: Beloved Boy: Letters to Hendrik C. Andersen 1899-1915. University of Virginia Press 2004. Quoted in Alex Wright: Cataloging the World.)

After this exchange of letters, the friendship between Andersen and James waned. Andersen peddled his World City to various heads of state and other prominent people. Through his Belgian contacts he got an audience with Albert, King of the Belgians, who was very encouraging, saying that one day it was certain to become a reality. No concrete help was forthcoming, though.

At the start of 1914 things were looking good for Paul Otlet. The World City was coming into focus, although the proposed sources of finance had proved to be largely illusory. The Union of International Associations had more than 150 members and the RBU surpassed 10 million entries. His close associate Henri Lafontaine was basking in the glory of the Nobel Peace Prize, which would certainly open more doors for both men.

Then war broke out.

Hope for the League of Nations

During the war, Otlet became an advocate of a new world order which would prevent war through international arbitration. This was rooted in his peace activism before the war and made him an advocate of the fledgling League of Nations. He campaigned to have the seat of the new organisation in Belgium, or at least the cultural and intellectual parts of it. At the time, it wasn’t precisely defined what form the new League of Nations would take, and there was a good chance that there would also be a cultural department, much like the later UNESCO. Otlet was firmly convinced that the best place for this organisation was his World City, and that it should be built near Brussels.

This earned him the renewed favour of the Belgian government, which was attempting to attract prestigious international institutions and maintain the pre-war role of Brussels as an international hub, though this favour fell short of strong financial support. When it became clear there was no chance of having even a branch of the League of Nations in Belgium, official enthusiasm for Otlet markedly cooled.

Meanwhile, things had also soured between Otlet and Andersen. Andersen had come to realise that the Belgian was better at drawing up plans and organising conferences than at providing funding and getting things done. He also rightly suspected that Otlet would be using Andersen’s plans to further his own vision of a Mundaneum, rather than supporting Andersen’s project.

During the 1920s, Andersen continued to pitch his idea to any politician who would listen, and found a sympathetic ear in Mussolini, a man who never saw a grandiose scheme he didn’t like. Mussolini needed no convincing that Rome was the obvious place to build a World City and considered dedicating a plot of land near Ostia to the project. This in turn led to Otlet writing an encouraging letter to Mussolini. Considering Otlet’s political background, this was a remarkable step.

As with all his other plans, nothing ever came of this.

Cité Radieuse and Cité Mondiale

One of the reasons the relation between Andersen and Otlet petered out in the second half of the 1920s, was that Otlet had found a new visionary architect: Le Corbusier.

Both men met in 1927, when Le Corbusier was still smarting from the rejection of his proposal for the League of Nations headquarters in Geneva. The competition to design the new headquarters had ended in confusion and farce. The jury had been unable to pick a winner from the 378 submissions, and instead decided to announce an eight-way tie for first place, none of which would be built. Le Corbusier’s project was one of the eight winners, but he understandably felt sabotaged by small-minded bureaucrats who were afraid to usher in a new era. Otlet knew exactly how he felt, and the two misunderstood geniuses immediately hit it off.

Le Corbusier and Otlet reworked Andersen’s idea of a World City to be centered around the Mundaneum (as the Musée Mondial was becoming known), which would be an active force to spread knowledge and increase mutual understanding between the peoples of the world.

They produced a pamphlet called Mundaneum, giving a concrete architectural form to the vision of a complex of buildings which would house all the knowledge of the world. I use the word ‘concrete’ advisedly because Le Corbusier was much more in tune with his time than the previous plans of Andersen and was a great advocate of le béton brute, i.e. visible concrete. Andersen was deeply rooted in the neoclassical style of the great pre-war exhibitions, with ornate domes, colonnades, arches and classicising monumental statuary; the kind of city that would be inhabited by an advanced race in an Edgar Rice Burroughs novel. Le Corbusier was all about functional steel, glass, and concrete with a healthy dose of Theosophist symbolism. Otlet was also into Theosophy. A few years earlier he had met Krishnamutri, the Theosophists’ spiritual leader, who influenced the philosophical basis of the project. This version of the Mundaneum included a Sacrarium, a cylindrical enclosure to channel spiritual energies, and which would reveal the hidden idea of the spirit of history itself. Visually the most striking part of the new city would be the Musée Mondial, as a ziggurat that would hold the world’s knowledge.

They proposed their new city to the League of Nations. The new World City, covering 566 hectares was to be built in Geneva, and incorporate the already existing buildings of the League of Nations. The estimated cost was $50,000,000 (almost $900,000,000 in 2024 money). To handle the finances, Otlet proposed creating a World Bank, a kind of supranational institution that didn’t yet exist at the time. This bank would administer the international war debts and reparations that had resulted from the Great War, which would provide it with the working capital to fund various projects in the interest of humanity. What the major financial institutions of the world thought of this plan is not known, because Otlet never thought of asking them. Otlet was hoping that Rockefeller would underwrite the World City. He was, as always, optimistic: he just needed $5,000,000 to get the ball the rolling and the rest could be raised through public subscription.

The initial reaction of the press and public was positive, as everyone was impressed by the scale and audacity of the project. This changed when the practicalities of the plan sank in. The Swiss especially took exception at Otlet’s idea that the new World City would be an extraterritorial zone. The Swiss were very proud of their independence and weren’t planning on relinquishing any part of the country just because a stray Belgian and Frenchman said so.

Then the Wall Street Crash happened, which made the whole question academic. This did not discourage the duo. Le Corbusier reworked his plans into what would become la Ville Radieuse (the Radiant City), and Otlet revived the prewar plans to build the World City near Brussels.

In 1932 a unique opportunity arose. The historical city of Antwerp had grown on the right bank of the Scheldt. To give the city room for expansion, a 3,000-hectare area on the left bank was added to the jurisdiction of Antwerp and a public company called Imalso was created to handle the development of the site. Imalso organised an architectural competition, which attracted widespread attention. Otlet reacted characteristically by sending a telegram to Le Corbusier: “excellent opportunity in Antwerp. Come next Saturday.” To which the architect testily replied that he was happy to discuss the Cité Mondiale, but that he couldn’t just drop everything to go to Antwerp. Anyway, before boarding a train he would need an exact address and an idea of who he would be meeting and why. Eventually, in 1933, Le Corbusier proposed a version of his Cité Radieuse housing 500,000 people, to be built on the left bank of the Scheldt, again including the Musée Mondial in the form of a ziggurat on the waterfront. True to form, Otlet added a political dimension, which would make Antwerp a free port and solve the question of the Dutch control of the Scheldt estuary by making the banks of the river into an international zone.

One wonders what the jury of Imalso, which was basically a real estate developer, made of this. Nothing ever came of the competition anyway, and no prizes were awarded. Imalso didn’t actually have the means to realise any of these grand projects and was simply using the competition to steal ideas.

This last failure proved the end of the collaboration between Le Corbusier and Otlet, although both men remained on amicable terms.

The battle for the Cinquantenaire

Meanwhile, all was not well in Brussels. After World War I, Otlet took up where he had left off with the Palais Mondial, which rapidly expanded to occupy more and more of the Cinquantenaire. Yet questions were being raised what he was doing in one of the most prestigious building complexes of the country.

The original plans for the Cinquantenaire to house important national museums were finally being realised, with the Army Museum occupying the north wing, and the Royal Museum for Art and History occupying the south wing. But the Palais Mondial still took up a good part the latter wing, notably the vast exhibition hall. Everyone understood and respected the bibliographical work of the RBU, but most of the space it had been allotted was occupied by the Palais Mondial for, well, what exactly?

Otlet’s view of a museum differed markedly from the traditional concept of the time — a collection of works of art or unique artifacts to be conserved and studied, exemplified by his neighbour, the Royal Museum of Art and History. Otlet, inspired by people like Geddes and Neurath, saw a museum first and foremost as a way of spreading and generating knowledge. He firmly believed in communicating information through visual means, by images, diagrams, photos and, as soon as technology would allow it, moving images. Hence the Palais Mondial was not so much a collection of unique and valuable objects, but one of ideas and representations. This also had an ideological foundation. The Palais Mondial was created to offer anyone an education. People, regardless of their background, could come in and learn about any subject under the sun. Otlet also saw it as a way to promote international understanding and counteract nationalistic propaganda, by allowing visitors to learn about other nations directly.

It had a certain measure of success. According to Otlet himself, the museum drew 50,000 visitors in 1923, including hundreds of school groups, a very respectable number for the time. Yet, for the scientific community of the time, not to mention official circles, this fell short of a true museum, and was more like a school museum that had gotten out of hand.

Here we come to another thing which annoyed Belgian officials: Otlet’s activism. Throughout this period Otlet, along with Henri and Léonie Lafontaine, was a tireless campaigner for causes like international cooperation and arbitration, votes for women, and anti-colonialism, none of which accorded with government policy of the time. In fact, the French government had refused him entry into the country in 1916 on the grounds of his ‘dangerous pacifism’. In 1921 the Palais Mondial hosted a Pan African congress that attracted black activists from around the world. This caused outrage in conservative circles and Otlet was accused of being in the pay of Moscow. (In the 1920s, anything that offended conservative circles in Belgium, was automatically considered a Bolshevik plot,) The Cinquantenaire was a public building and in official circles people started to wonder why Otlet should have access to the infrastructure, if he would be using it to organise events which went directly against government policy. The space, and especially the great exhibition hall, could be used for a more profitable purpose, such as trade fairs.

It didn’t help that the actual execution of the Palais Mondial fell far short of its lofty ideals. The collection had started as the remnants of a universal exhibition and the UIA never had the money and staff to keep it up to date or even develop a coherent museological concept. The collection grew haphazardly, mainly through donations, and the general impression was that of amateurism and improvisation.

In 1924 the Palais Mondial was requisitioned to make room for a rubber trade fair. Given Otlet’s views on colonialism and the link between rubber and the Congo, this was adding insult to injury. Although Otlet put up a tenacious defence, even blocking the door with filing cabinets when workers arrived, it was to no avail. The Palais Mondial had to make way for the rubber industry.

Enter Capart

After the end of the trade fair the UIA reclaimed their rooms in the Cinquantenaire, but the writing was on the wall. The Belgian government was no longer interested in supporting either the UIA or the bibliographical effort, and funding was cut.

This caused a significant shift in the workings of the IIB, the bibliographical sister organisation which ran the RBU. Taken up by the dream of the Cité Mondial and the Mundaneum, Otlet had been devoting less and less energy to his bibliographical activities. The expansion of the catalogue slowed down considerably. To put it back on the rails, Frits Donker Duyvis, an energetic Dutchman, was engaged as a secretary in 1921. Donker Duyvis steered the orgnisation’s activities away from compiling bibliographies and towards developing the UDC, an idea which he rightly thought had more of a future. When in 1924 they had to leave the premises, he moved the cataloguing activities to The Hague, to concentrate on the UDC, an activity that continues to this day.

Meanwhile a formidable rival had appeared for the use of the Cinquantenaire: Jean Capart. He was an eminent Egyptologist, determined to put Belgium on the map as a world center of Egyptology, and needed a space to display his Egyptian discoveries properly. He was something of a celebrity, accompanying the then Prince Leopold and Queen Elisabeth (that is Queen of Elisabeth of Belgium, not the more famous one of Britain) on a much-publicised trip to Egypt. He was also the model for professor Bergamot in the Tintin adventure Les Sept Boules de Cristal (the Seven Crystal Balls). Unlike Otlet, who only had diagrams and assorted bits and pieces to show, Capart did have true treasures and antiquities, fresh from his excavations. Add to that a bout of Egyptomania, triggered by the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun, and it was quickly obvious who would be the winner. In 1934, the axe fell. The Belgian government decided to allocate the South Wing of the Cinquantenaire to the Royal Museum of Art and History, reminding the UIA that their use of the rooms had been granted as à titre précaire, a privilege which could be recalled at any moment. The locks were changed and Otlet was refused entry.

Protests were lodged and a legal battle started between the Belgian government and the UIA. This left the collections in limbo. They were piled up in the parts of the Cinquantenaire that the Royal Museum of Art History wasn’t using, notably the exhibition hall, but remained inaccessible to Otlet. In the eyes of the public, Otlet had become a figure of fun, the punchline of a joke. The newspaper De Standaard could write in 1927: “God preserve us from a Mundaneum à la Otlet, because there are people who would fill every public building with index cards, if we let them.” In a 1951 article about the episode, the newspaper Le Soir described the Mundaneum as “one these absurd collections that obsessive minds spend their lives gathering.”

This was not the end of the Mundaneum. Otlet continued his work as best he could from his home, writing Traité de Documentation, the synthesis of his views on the collecting, cataloguing and dissemination of information. Meanwhile Donker Duyvis continued to promote the UDC from The Hague. Conferences continued to be organised, and in February 1940, the 1.000th conference of the Mundaneum was celebrated.

As for the collections, they gathered dust until the Germans invaded in May 1940. The Nazis wanted to use the building for themselves and sent along an inspection team to see whether there was anything worth keeping. They were singularly unimpressed by the hodgepodge of the exhibits, calling them embarrassingly cheap and primitive, though they did think that the card catalogue might have some use. They cleared out everything and destroyed most of the exhibits, including two derelict airplanes. Otlet was allowed to keep filing cabinets and archives, and his friends on the Brussels City Council found a place where these could be stored.

After the death of Otlet in 1944, his friends and disciples organised as the Amis du Palais Mondial (Friends of the World Palace). They kept on organising talks and excursions under the banner of the Mundaneum until at least 1970. They also cared for what was left of the collection and archive, which moved from one temporary location to another, getting smaller and smaller after each move. Eventually the collection ended up in the care of the ministry of Francophone culture of Belgium. (No doubt listeners familiar with Belgium are already writing in that there is no such thing, but if you want me to explain the Belgium administrative state we’ll be here forever. So, I’m simplifying.)

In the meantime, with the rise of the computer and information networks, interest in Otlet and his ideas had rekindled. The archives and filing cabinets eventually ended up in the city of Mons, where in 1993 a new museum was created. This was called the Mundaneum and highlighted the work of Otlet and Henri and Léonie Lafontaine. The centerpiece is formed by some of the filing cabinets of the RBU, along with many archival pieces.

Steampunk Google

What rekindled modern interest in Paul Otlet were his views on the organisation and dissemination of knowledge. Phrases like ‘the paper Internet’ or ‘the inventor of the Internet’ are often used when describing his work. These are gross exaggerations, but Otlet’s ideas on the subject did prove to be farsighted.

For all his work in bibliography, Otlet was painfully aware of the limitations of printed books. It was one thing to know that a book existed, but all too often there were only a few copies available in a handful of libraries, which might make the information they contained difficult to access. He was constantly looking for ways in which books (or index cards for that matter) could be easily reproduced and/or rendered accessible over long distances.

One of his early concepts from 1906 was the Bibliophote, a device which copied books to microfilm. These microfilms could then be projected on any flat surface to be read. This greatly reduced the storage space a library would need and allowed books to be quickly copied and made accessible. It was very much an early version of digitising books and putting them on the Internet.

Photography in all its forms held a special fascination for Otlet. He believed visual representations of information were at least as important as linguistic means, if not more so. The Mundaneum would also include an extensive collection of photographs and other visual documents.

Over time his thinking moved away from the traditional book to the concept of ‘document’ which could be a vector of information in many forms. Otlet called the basic unit of information a ‘biblion’, which would be to the science of documentation what the atom was to physics. A biblion could take on any form: books of course, but also articles, photographs, brochures, sound recordings or even road signs. His ideal was to extract the information from books and other media and present it in synthetic form. This way everyone would become their own editor. Readers were no longer limited to the author-controlled flow of information but would assemble individual biblia into a coherent whole of their own making.

It’s hardly surprising that internet pioneers found Otlet’s ideas inspiring.

One of his preferred methods of presenting knowledge was what we would now call the infographic: presenting information through a combination of text and images. For his Palais Mondial, Otlet commissioned thousands of plates by the artist Alfred Corbin covering a wide range of scientific and historical topics. These plates could then be reproduced for use in local museums and schools. In this he was influenced by Otto Neurath’s ideas for making use of the rapidly growing codes of visual communication for spreading information. Of course, both men met and their relationship followed the familiar pattern of initial enthusiasm and the creation of ambitious plans, followed by disappointment and separation. Neurath and Otlet’s joint venture was to be called Novis Orbis Pictus (or “the new painted world”). It would consist of a chain of syndicated museum displays, as well as mobile exhibitions of cars equipped with cinema projectors, moving one step further from the museum as concrete entity contained in a single building, to the museum as a repository of knowledge (now we’d say content) that could be reproduced anywhere. The project was short lived. For one thing the Wall Street Crash made all sources of funding disappear. For another, both men each had a strong vision, with different priorities. Neurath wanted to create a visual language to educate the working classes, while Otlet wanted to build a repository of all human knowledge.

Otlet hoped advances in technology would make his vision of universally distributed knowledge a reality. He had a keen eye for what was already possible with existing technology, such as the bibliophote. He also proposed using the telephone for hybrid conferences, where some participants would attend in person, and others remotely. After the development of television, he imagined that it would be possible to have pages from a book projected remotely, so that you no longer needed access to a physical copy to read it. In his Traité de Documentation, he outlined a system for simultaneous translation, in which translators would type their text unto translucent tapes, which would then be projected above the orator. This would also allow for simultaneous translation into multiple languages and, he added, might eliminate the need for blackboards in education. He did, however, hope that the adoption of Esperanto would make any need for translation in international conferences superfluous.

Perhaps his most farsighted concept was the Mondothèque. This can best be described as an analog workstation built with 1930s technology. It was a desk-like device equipped with various electronic instruments (radio, telephone, microfilm reader, television, and record player) and containing a number of reference books, such as the Universal Decimal Classification. The Mondothèque would be connected to the universal network of documentation, so that the user could compile a selection of documents, either in written form or as sound and visual recordings, to suit their own needs. Ideally, it would also have a system to translate speech into text, and a means to retrieve documents automatically. The device would also be able to index documents mechanically in the form of punch cards and reproduce them in any quantity needed. In this way the Mondothèque would not just be a system for consulting documents but would be able to produce new ones as a part of the universal network of documentation.

Let’s not be petty and microphile

So, what to think of Paul Otlet?

His most enduring legacy is no doubt the UDC, which is still used today by many libraries around the world. Donker Duyvis no doubt made the smart choice in the 1920s when he concentrated his efforts on developing and promoting the classification system, rather than trying to build a world capital.

Most of Otlet’s other visions were far too grandiose to have any chance of being realised. He truly was the utopians’ utopian. He had a knack for taking any utopian project, no matter how ambitious, and then turning it up to eleven. Dreaming big was his defining characteristic, or as he said it himself in his introduction to one of his projects of the Cité Mondial: «ne soyons pas mesquins et microphiles» (‘let’s not be petty and microphile’), coining a new word at the same time.

He was also an irrepressible optimist, firmly believing that, if he explained things clearly, people would automatically come around to his point of view. This led him to believe that it would be easy to obtain funding for his various projects, whether from Leopold II, Carnegie, Rockefeller, or a hypothetical world bank. All he needed to do was to present the idea to the people in power and the rest would follow automatically. That same optimism led him to launch an appeal in June 1940 to world leaders not to let the current war stand in the way of creating the Cité Mondial and asking them to support the project. Among the recipients were Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Churchill, Pope Pius XII, and somewhat more surprisingly, Stalin, Pétain, Franco, Mussolini, and Hitler. To provide some context, June 1940 saw Germany’s victory in the West, with the Low Countries occupied, France collapsing, the British army leaving the continent and Italy entering the war. This was when Churchill gave his ‘Darkest Hour’ speech. Otlet’s grasp of the political realities of the day left a lot to be desired. It would be easy to call him naive, but there’s something admirable in someone who is determined to think the best of everyone.

For all Otlet’s neglect for practical feasibility and the state of the art of technology, his visions weren’t purely utopian pipe dreams. Many of his ideas were truly ahead of their time and were finally realised when conditions changed and technology made them possible. Indeed, his basic vision of a comprehensive and accurately classified catalogue with a service that would provide bibliographies on demand can be seen as a proto search engine. Likewise, his insistence on looking beyond the book and including visual and audio elements as carriers of information, which would then be transferred electronically to any point in the world, makes him an early pioneer of multimedia and the world wide web. If you are producing steampunk fiction and are wondering what the internet might have looked like in the 1920s, Otlet has got you covered.

It is fair to say that Otlet the utopian was detrimental to Otlet the information theorist. It is telling that his magnum opus on the subject, the Traité de Documentation, was only written in 1934, after he had been shut out from the Cinquantenaire. If he had continued to develop the RBU instead of losing himself in successive projects of a Mundaneum, he might have achieved something like an analogue search engine. His idea of a central institute producing bibliographies on demand was certainly feasible, if expensive and laborious. But then his life would have been much less interesting and inspiring.

Images used with the permission of the Collection Mundaneum, and cannot be reproduced without permission.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

Otlet was really into Esperanto, the international language. You know who else was really into Esperanto? Wilhelm Molly, who in 1908 attempted to convert the interernational no-mans-land of Neutral Moresnet (“Independent by Accident”) into the Esperanto capital of the world.

Le Corbusier was also highly influential on the life of another utopian dreamer, R. Buckminster Fuller (“Fuller Houses”), who sought to revolutionize society through mass-produced housing.

If the concept of a “Sacrarium” focusing the world’s spiritual energies on one spot sounds familiar, that may be because a similar (if more explicitly sexual) version of the idea occurs in the writings of Dr. Cyrus Reed Teed (“We Live Inside”). Teed’s “anthropostic battery” was supposed to supercharge his “theocrasis” and allow him to unite with the feminine aspect of the Godhead to create Heaven on Earth.

Otlet wasn’t the only person trying to sell grandiose ideas to Mussolini. Bugsy Siegel and the Countess Dorothy di Frasso (“The Realest Housewife of Beverly Hills”) once tried to sell Il Duce an experimental explosive called “radium-atomite.” It didn’t end well for them either.

Amazingly, this isn’t the podcast’s first brush with Tintin. Belgian cryptozoologist Bernard Heuvelmans (“The Ape-Man Creature of Whiteface Customized My Van”) once consulted with Hergé to ensure that the yeti in Tintin in Tibet was depicted as accurately as possible.

Sources

- Alex Wright: Cataloging the World. Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age. Oxford University Press. 2014.

- Françoise Levie: L’homme qui voulait classer le monde. Paul Otlet et le Mundaneum. Les impressions nouvelles. 2006.

- Paul Otlet. Fondateur du Mundaneum (1868 – 1944). Architecte du savoir, Artisan de paix. Les impressions nouvelles. 2010.

- Paul Otlet : Traité de documentation. Le livre sur le livre. Centre de Lecture publique de la Communauté française de Belgique. 1989.

- Newspaper archive of the KBR

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: