Suffer Little Children

John Ballou Newbrough, Oahspe, and the Faithists of SHalam

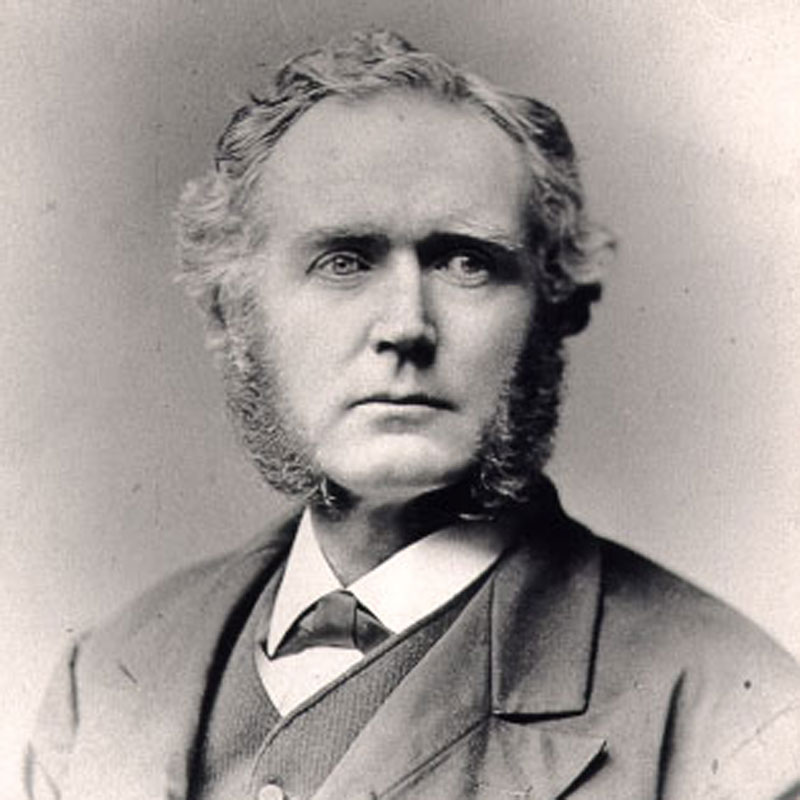

John Ballou Newbrough

John Ballou Newbrough was born on June 3, 1828 in Mohecanville, Ohio. His parents, William and Elizabeth, named him after the famed Universalist preacher John Ballou, who they admired.

He was a bright young boy, and in 1844 when he turned sixteen his parents sent him off to to study at Cleveland Medical College. His medical career almost ended before it began when young John discovered that he was hypersensitive to the pain and suffering of his patients and could barely stand the sight of blood.

Rather than abandon his expensive education, he changed his focus from medicine to dentistry. Now, it strikes me that 19th century dentistry was just as bloody and painful as other fields of medicine, but I suppose it had the major advantage that most of the blood tended to stay inside the patients. Or at least inside their mouths.

By the time he graduated in 1849, J.B. Newbrough had grown into a large young man, and I do mean large — he stood 6’4″ tall and weighed 270 pounds. But perched on top of the body of a linebacker was the face of an angel, featuring a high forehead, chubby cheeks, large hazel eyes, sensitive lips, and a mane of soft wavy hair. He had a deep, soft voice that was simultaneously gentle, reassuring, and authoritative. The combined effect was commanding. Regal, even.

After graduation, Dr. J.B. Newbrough did not jump right into the practice of medicine. Instead, he he got swept up in the chaos of the California gold rush. On his journey to the Golden State he met a Scotsman, John Turnbull. The two men became fast friends and business partners. They made good money in California, but when good claims became slim pickings the two men sailed to Australia to join the Ballarat gold rush.

When he returned to the United States in 1855, Newbrough was… well, not a wealthy man but certainly a comfortable one. Like a lot of ambitious young men of means, he set his sights on a noble task: writing the great American novel.

The Lady of the West, or, The Gold Seekers, is turgid roman à clef featuring thinly disguised versions of Newbrough and Turnbull as they romance their way through the gold fields of California. It’s a deeply strange book, alternating chapters of bargain-basement adventure with chapters bloviating about the hot-button issues of the day. Over the course of its 500 pages Newbrough shares his rather negative opinions about suffragettes, abolitionists, hypocrisy, taxation, and even the very concept of democracy. At the same time, he also condemns xenophobia, advocates for unrestricted immigration from Asian countries, and promotes the mixing of the races.

Needless to say, The Lady of the West didn’t set the literary world on fire, so Newbrough resumed his dental practice. Thanks to the presence of the medical school Cincinnati was lousy with dentists, so he moved west to Dayton, and then to St. Louis.

In 1859, Newbrough traveled to Scotland to visit his old business partner, and on the trip he fell in love with Turnbull’s younger sister Rachel. The two were soon married. The newlyweds returned to America in 1860, settling in Philadelphia for a two years before permanently relocating to New York City.

With his literary ambitions stifled, Newbrough took up another great American passion: inventing. Over the years he received patents for all sorts of devices: artificial teeth, exercise machines, furnaces, railway cars. From a modern perspective, his most impressive invention was a mechanical adding machine. For the most part his inventions languished in obscurity.

Then in 1868 he developed a process for creating dental plates out of what he called “whalebone rubber.” He wrote a short pamphlet, A Catechism of Human Teeth, to spread the word about his invention and began offering low-cost dentures for sale to the poor.

It was a huge success. There was only one problem: his whalebone rubber dentures were priced to undercut the vulcanized rubber dentures offered by Charles Goodyear’s Dental Rubber Company.

Goodyear sued, claiming patent infringement, and while Newbrough staged a successful defense of his patents he found the legal process exhausting. He ultimately wound up abandoning his patents and focusing on the day-to-day business of dentistry.

It was a largely uneventful career, though it had its hazards. In 1872, Newbrough killed one of his patients by administering an overdose of nitrous oxide. A medical inquest ruled that the death was accidental, though the coroner chided Newbrough for failing to seek medical aid as his patient lay dying on the floor of his office.

Angel Embassadors

At this point in our tale, Dr. John Ballou Newbrough has already lived a ludicrously full and eventful life. So prepare to be astounded when I tell you that his temporal accomplishments paled in comparison to his spiritual ones.

John’s mother, Elizabeth Newbrough, could see ghosts and spirits, an ability that her son claimed to have inherited. Alas, his father had no time for blasphemous nonsense. Whenever young John started talking about his second sight, William Newbrough would grab a switch and administer corporal punishment to his son. But even regular beatings could not disabuse John of his belief in the supernatural.

During his time in California, Newbrough befriended several Chinese laborers and became fascinated with their religion. That eventually evolved into a general interest in world religions. Over the years he would read the sacred books of major world religions including Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. He also had a taste for the esoteric and forbidden, studying Zoroastrianism, Egyptian mysticism, and Christian Gnosticism.

This dovetailed nicely with his interest in Freemasonry. He eventually rose through the ranks to become a 33rd degree Master Mason. Make of that what you will.

When the Spiritualist movement took off in the middle of the century, Newbrough was one of its most active participants.

For two years, he was a member of “The Domain,” a Spiritualist colony in Kiantone, New York. Newbrough had been attracted to the group because it advocated for progressive ideas which mirrored his own, including the promotion of race-mixing and the abolition of national governments.

Alas, the Domain fell apart in the late 1850s. First, a sex scandal involving several prominent members brought them unwanted attention. Then, as a distraction, they launched an international campaign to petition national governments to devolve their authority to a one-world government guided by voices from the spirit world. They quickly ran through their money and were forced to cease operations.

Newbrough left the Domain when the sex scandal broke, and instead became a big shot in New York City’s Spiritualist circles. He was a trustee of the New York Spiritualist Association and served on its Protective Committee, which tested and weeded out fraudulent mediums. As the newspapers noted, he had some rather unique qualifications for the job:

Dr. Newbrough is a jolly fat person and weighs 245 pounds. He is far from spiritual or ethereal in appearance and the spirit that raises him has got to have plenty of power of some sort.

At some point, Newbrough began to feel unsatisfied. Conversing with the spirits of the dead was old hat, and he craved answers to deeper questions. Questions about human suffering and morality, questions about the nature of God and the universe. Questions whose answers remained frustratingly outside of his reach.

Newbrough became convinced that ideomotor actions — unconscious and involuntary muscle movements — were actually the result of transmissions broadcast into his body from the spirit world. In 1870, he resolved to purify his mind and body so that he could finally perceive the message.

To purify his body, he completely changed his diet. He cut out red meat, and then all animal flesh, and then only ate food that had “received the beneficent rays of the sun.” In the end Newbrough went full vegan, and it did wonders for his health. He lost 110 pounds and his chronic rheumatism and migraine headaches disappeared.

To cleanse his mind, Newbrough woke each day before dawn and sat alone in his study, contemplating his flaws and confessing his sins to God as he watched the sun rise.

He also swore himself to chastity, which Mrs. Rachel Newbrough didn’t like at all.

After eight years, Newbrough finally began to understand the message. Angels from the other side guided his hands to produce automatic writings, drawings and paintings in great quantities.

It still wasn’t enough, and he asked for more. I’ll let Dr. Newbrough tell you what happened next in his own words.

I was crying for the light of Heaven. I did not desire communication for friends or relatives or information about earthly things; I wished to learn something about the spirit world, what the angels did, how they traveled, and the general plan of the universe…

I was directed to get a typewriter which writes by keys, like a piano. This I did and I applied myself industriously to learn it, but with only indifferent success. For two years more the angels propounded to me questions relative to heaven and Earth, which no mortal could answer very intelligently…

One morning the light struck both hands on the back, and they went for the typewriter for some fifteen minutes very rigorously. I was told not to read what was printed, and I have worked myself into such a religious fear of losing this new power that I obeyed reverently. The next morning, also before sunrise the same power came and wrote (or printed rather) again. Again I laid the matter away very religiously, saying little about it to anybody. One morning I accidentally (seemed accidental to me) looked out the window and beheld the line of light that rested on my hands extending heavenward like a telegraph wire toward the sky. Over my head were three pairs of hands, fully materialized; behind me stood another angel with her hands on my shoulders. My looking did not disturb the scene, my hands kept right on printing…

For fifty weeks this continued every morning, half an hour or so before sunrise, and then it ceased, and I was told to read and publish the book Oahspe.

Earth, Sky and Spirit

More formally, that title is: Oahspe: A New Bible in the Words of Jehovih and His Angel Embassadors; A Sacred History of the Dominions of the Higher and Lower Heavens on the Earth for the Past Twenty-Four Thousand Years, Together with a Synoposis of the Cosmogony of the Universe; The Creation of Planets; The Creation of Man; The Unseen Worlds; The Labor and Glory of Gods and Goddesses in the Etherean Heavens; With the New Commandments of Jehovih to Man of the Present Day, with Revelations from the Second Resurrection, Formed in Words in the Thirty-Third Year of the Kosmon Era.

The Oahspe was a 1,000 page behemoth that purported to recount the entire history of the universe, as transmitted directly from the mind of God to the hands of John Ballou Newbrough.

Here are the highlights.

In the beginning the infinitely supreme Jehovih (that’s “Jehovih” with an i) created the universe.

The universe is split between Corpor, the material world we all inhabit, and Es, the spirit world. Es is further divided into the rarefied Etherea, where Jehovih dwelleth, and the ever-changing realm of Atmospheria, which contains numerous “heavens” and “hells.” Angels and spirits traverse these realms using fire-ships and star-ships.

The day-to-day maintenance of Corpor is handled by angels who are sorted and ranked with titles like marshal, lord, and god. There are also sub-gods and vice-gods. The supreme angel is bestowed with the ceremonial title Son (or Daughter) of Jehovih. Once they’ve attained that rank they can build a tower and attract men-at-arms.

When a human being dies, their soul is released. The gods and goddesses test the souls like some sort of cosmic USDA inspector, and those spirits with sufficient power are allowed to pass from Corpor into Es and set upon the Cevorkum of the Solar Phalanx, the path that leads towards angelhood and godhood.

For the untold millennia this system operated perfectly, through the reigns of:

- Sethantes, First God of the Earth and Her Heavens;

- Ah’shong, sub-Chief in the realms of Hieu Wee in the Haian arc of Vehetaivi;

- Hoo Lee, surveyor of Kakayen’sta in the arc of Gimmel;

- C’pe Aban, Chieftaness of Sulgoweron in the arc of Yan;

- Pathodices, road-maker in Chitivya in the arc of Yahomitak;

- Goemagak, God of Iseg, in the arc of Somgwotha;

- Goepens, God of Kaim, in the arc of Srivat;

- Hycis, Goddess of Ruts, in the arc of Hohamagollak;

- Se’icitus, inspector of roads in Kammatra, in the arc of Jusyin;

- Miscelitivi, Chieftaness of the arches of Lawzgowbak in the arc of Nu;

- Gobath, God of Tirongothaga, in the arc of Su’le;

- F’ayis, Goddess of Looga, in the arc of Siyan;

- Zineathaes, keeper of the Cress, in the arc of Oleganaya;

- Tothsentaga, road-maker in Hapanogos, in the arc of Manechu;

- and Nimeas, God of Thosgothamachus, in the arc of Seigga.

In the sixteenth cycle, during the reign of Neph, God of Sogghones, in the arc of Arbroohk, something went very wrong. The collective souls of humanity were judged to be of grade 50 or lower, and unfit to pass into the spirit world.

When Aph, Son of Jehovih, looked upon the world he aw the problem at once. The world had once been populated by the race of I’hins; beautiful, pale and slender, the offspring of angels and humans. Over time the I’hins had interbred with the fat, ugly, dark and animalistic druks. Their offspring were cannibals, vampires and worse. To prevent the physical and spiritual corruption from spreading further, Aph sunk the land of the I’hins beneath the waves.

This mighty continent, called Wagga or Pan, once linked Australia, Asia and North America. After it sunk beneath the waves of the Pacific Ocean only its northern portion, the islands of Ja-Pan, remained above the waves. The survivors of the deluge spread out across the world and their language of Ah-ce-o-ga was forgotten, though elements of this universal “Panic” or “Paneric” language remain in our modern languages.

(“O-ah-spe”, if you care, is a Panic word meaning “earth, sky, and spirit.”)

It’s Atlantis and Noah’s Ark and the Tower of Babel, all rolled into one.

That was about 24,000 years ago, and it established a pattern for the nature of the world: a downward spiral. Apparently when it left to its own devices, Corpor inevitably degrades into barbarism and depravity and the gods must hit the cosmic reset button. Alas, the renewed world never quite seems to reach the same spiritual heights…

In the previous era of man, the unthinkable happened. At the time three gods, Kabalactes of Horactu, Enochissa of Eta-Shong, and Looeamong of Hapsendi, ruled the world as the Confederacy of the Holy Ghost. But the Confederates were hungry for power and susceptible to the temptations of Satan. They rebelled against Jehovih and began their own religions. Kabalactes became “Brahma”, Enochissa became “Buddha,” and Looeamong became “Kriste.”

(I should clarify that there was a real Jesus of Nazareth, though little of his teachings remain in the Bible. Kriste manifested himself to Constantine at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and gave him the power to overthrow Maxentius. At the Council of Nicea the new emperor forced his new “Kriste’yan” faith of conquest on the peaceful Christians.)

The Confederates declared war on the spiritual realm, captured all the other gods of Corpor and some 7,600,000 angels, and cast them into the fiery pit of Makavishtu. After this great victory, Looeamong’s trusted marshal Thoth (or possibly “Gabriel”) split from the Confederacy and established the Islamic faith.

Which brings us to the present day, where all the major world religions were created by false gods, and all our souls are doomed to hell when we die as a result.

And yet you should rejoice, for there is hope.

When Spiritualists began to pierce the veil between Corpor and Es it marked the dawn of a new age, the Kosmon Era, which allowed Jehovih’s angel embassadors to reveal the true nature of the world through the medium of John Ballou Newbrough. If humanity turns away from their false gods and returns to the worship of Jehovih, their souls can be saved.

The path to salvation is outlined in the final book of the Oahspe, the Book of Jehovih’s Kingdom on Earth, which is also known as the Book of Shalam. It is the only part of the book which is presented as ante-script, or prophecy, rather than history. It recounts the tale of a humble and faithful man named Tae and his soulmate Es, who lead a group of devout Faithists into the desert to establish a commune.

In the land of Shalam, free from the corrupting influence of the modern world, the Faithists raise a group of orphan babes and castaway infants and foundlings of all races in the true faith of Jehovih. (Children are deemed ideal for this experiment because they unformed, unlike adults who have to be arduously re-educated.) The Faithists take care of all the children’s material needs and educate them in a sort of religious-themed Montessori school where they learn by questioning and doing.

When the children reach adulthood they are beautiful and wise, and their innate purity and perfection convinces the rest of the world to abandon materialism and selfishness. All world governments are dissolved, and we are ushered into a golden age by a new race of man.

It’s the most pleasant apocalypse I’ve ever read, the triumph of the good through manifest righteousness, with no violence or war or divine retribution in sight.

I realize that’s a lot to digest. But that summary doesn’t even begin to convey the utter madness of the Oahspe, most of which comes from its writing style. I’m going to give you just a brief taste, from chapter two of the Book of Aph, Son of Jehovih:

I, Aph, Son of Jehovih, high dwelling in the Etherean worlds, and oft trained in the change and tumult of corporeal worlds, answered Jehovih, saying:

Father of Worlds; Jehovih, Almighty! Thy Son and servant hath heard Thy voice. Behold, my head is bowed, my knee bent to rush forth with a thousand million force to the suffering earth and hada.

Hear me, O angels of the earth’s heaven; from Jehovih’s everlasting kingdoms, I speak, and by His Power reveal! Again His Voice coursed the high heavens along where angels dwell, older than the earth. Jehovih said:

Hear Me, O ye Chieftains, of Or and of Oot, and in the plains of Gibrathatova. Proclaim My word to thy hosts of swift messengers of Wauk’awauk and Beliathon and Dor, and they shall speed it abroad in the a’ji’an mounds of Mentabraw and Kax of Gowh. Hear My voice, O ye Goddesses of Ho’etaivi and of Vaivi’yoni’rom in the Etherean arcs of Fas and Leigge, and Omaza. Proclaim My decrees of the red star and her heavens in the crash of her rebellious sides, for I will harvest in the forests of Seth and Raim. Hear My voice, O ye H’monkensoughts, of millions of years standing, and managers of corporeal worlds! I have proclaimed the uz and hiss of the red star in her pride and glory. Send word abroad in the highway of Plumf’goe to the great high Gods, Miantaf in the Etherean vortices of Bain, and to Rome and to Nesh’outoza and Du’ji. Hear Me, O ye Orian Kings and Queens of thousands of millions of Gods and Goddesses: I have spoken in the c’vork’um of the great serpent of the sun! A wave of My breath speedeth forth in the broad firmament. The red star flieth toward the point of My whetted sword.

Proclaim My voice in the Orian fields of Amal and Wawa; let the clear-tongued Shepherds of Zouias, and Berk, and Gaub, and Domfariana, fly with all speed in the road of Axyaya, where first the red star’s vortex gathered up its nebulae, millions of years agone, and on the way say: Jehovih hath decreed a pruning-knife to a traveling world.

Shout it abroad in the crystal heavens of the summering Lords of Wok and Ghi and M’goe and Ut’taw; call them to the red star speeding forth. Lo, she skippeth as a lamb to be shorn; her coming shock lieth slumbering low. Let them carry the sound of My voice to the ji’ay’an swamps of exploded worlds, boiling in the roar of elements, where wise angels and Gods explore to find the mystery of My handiwork.

Tell them I have spoken, and the earth and her heavens near the troughs in the Etherean seas of My rich-yielding worlds. I will scoop her up as a toy, and her vortex shall close about like a serpent hungry for its prey. Proclaim it in Thessa and Kau and Tin’wak’wak, and send them to Gitchefom of Januk and Dun.

Hear Me, O ye Kriss’helmatsholdak, who have witnessed the creation of many worlds and their going out. Open your gardens and your mansions; the seine of My fishing-pole is stretched; countless millions of druj and fetals will fall into My net. My voice hath gone forth in Chem’gow and Loo and Abroth, and Huitavi, and Kuts of Mas in the wide etherean fields of Rod’owkski.

Haleb hath heard Me; Borg, Hom, Zi and Luth, of the Orian homestead, and Chor, whence emanate the central tones of music, from Goddesses older than the corporeal worlds. To them the crash of worlds is as a note created, and is rich in stirring the memory with things long past.

I have spoken, and My breath is a floating world; My speech is written in the lines where travel countless millions of suns and stars; and in the midst of the Etherean firmament of the homes of Gods. Let them shout to the ends of the universe; invite them in My name to the hi’dan of Mauk’beiang’jow.

Around about in the place of the great serpent send swift messengers with the words of My decree; bring the Lords and Gods of Wan and Anah and Anakaron and Sith. Call up Ghad and Adonya and Etisyai and Onesyi and the hosts of the upraised, for the past time of Jehovih’s sons and daughters in the high heavens draweth near.

The Book of Aph, Son of Jehovih 2:1-14

I’m particularly glad that these lovely children were here today to hear that speech. Not only was it authentic frontier gibberish, it expressed a courage little seen in this day and age.

That’s just one page of the Oahspe. One entire page that can be boiled down to “Aph said Jehovih called for a gathering of the heavenly hosts.” And it’s actually a fairly representative passage. A good 50% or more of the text is needless filler which apes the style and structure of the King James Bible in an attempt to steal its gravitas.

The Oahspe is a fascinating relic of its time. It’s a bible driven by the Theosophistic urge to unify all world religions into a single framework, albeit one heavily influenced by Eastern religion and Gnosticism and Freemasonry. It’s a history that tries to present a comprehensive chronicle of the universe filtered through the bizarre preoccupations of an alienated white man in 19th-century America. I can’t think of another book where Osiris gets equal page time with Cotton Mather, and where the East India Company is revealed to be a literal tool of the devil.

And those names! I’m amazed no one has mined this book to get material for their Dungeons & Dragons campaign. Or at the very least an Empire of the Petal Throne campaign.

But I digress.

The Faithists of the Seal of Abraham

So John Ballou Newbrough had a book. Now he just needed a publisher.

Fortunately, he found one in the form of philanthropist Elizabeth Rowell Thompson, who moved in the same Spiritualist circles as Newbrough. She was drawn to the Oahspe because the divinely-ordained educational system outlined in the Book of Shalam incorporated many of the educational reforms and pedagogical techniques she advocated for in real life. (Such an interesting coincidence, that.) Thompson underwrote the first edition of the book, some 3,000 copies in total. They began circulating in early 1882.

The message of the Oahspe resonated with the Spiritualist community, who began converting to the worship of Jehovih, or “Faithism.” Faithist lodges were set up in New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, and St. Louis. Newbrough himself officiated ceremonies at the New York lodge, which were conveniently adjacent to his dental practice on West 34th Street.

The Faithist creed was a simple one.

- Jehovih the creator is the only true god. You should love him with all of your heart, all the days of your lives. All other religions are false religions whose worshippers are being misled by devils and drujahs. They are not to be mocked, but pitied.

- Other religious texts were written thousands of years ago in a world that no longer exists. The Oahspe was transmitted from the mind of Jehovih in contemporary times and thus is actually relevant to our modern world.

- Do not kill. In fact, do not condone or endorse violence of any kind, emotional as well as physical.

- This extends to your diet as well. Stick to a vegan diet, and forswear all intoxicants.

- All races are equal in the eyes of Jehovih. Interestingly, the sexes were not considered equal, as in many contemporary alternative religions; in fact, Faithism often reinforces traditional gender roles.

- The best government is no government. In ideal world, individuals and communities naturally act in accordance with divine guidance provided through su’is and sar’gis (extra-sensory perception).

- Some Faithists advocated for free love, and others for celibacy, but officially the religion endorsed neither position. Faithists were not allowed to divorce or remarry. One shot was all you got, so make sure you were marrying your soulmate. Also, they believed in soulmates.

One notable convert to Faithism was Dr. Henry Samuel Tanner. Tanner was the celebrity diet doctor of the 1880s, a physician who advocated for fasting as a treatment for disease. He made headlines in 1879 by claiming to have completed a biblically-inspired 40-day fast. No one believed him, so he recreated the feat in 1880 on the stage of Clarenden Hall in Manhattan. And made good money by charging looky-loos 25¢ for the privilege of watching a man not eat. Tanner was touted as “the Boss Hero of the Age” and his conversion brought the Faithists an enormous amount of publicity. Perhaps too much publicity. Reporters and the general public tended to assume that Tanner was the head of the Faithists, purely because he was the most famous person involved, and nothing Tanner or Newbrough said could disabuse them of this notion.

The most important convert, though, was Andrew Moore Howland. Howland was the scion of a rich and famous New England whaling family. How rich and famous? Well, so rich that one of Howland’s first cousins was Hetty Green, the fabled “Witch of Wall Street.” So famous there’s an island in the South Pacific named after them — and if the name “Howland Island” rings a bell, it’s because it’s the island Amelia Earhart never landed on. Howland brought the Faithists something even more important than publicity: money. While not quite as rich as his cousins, he still had a small fortune at his disposal and was not shy about opening his pocketbook.

It’s probably worth noting that Tanner and Howland were both Freemasons.

From the beginning, the Faithists were driven to create the socialist utopia prophesied by the Book of Shalam, where orphan babes and castaway infants and foundlings would be raised to be the perfect saviors of mankind.

The first attempt was somewhat discouraging, a commune in Woodside, New Jersey that fell apart after a few months. Nevertheless, they persisted. In November 1883 a huge gathering of Faithists from across the United States reaffirmed their commitment to the cause. Afterwards Newbrough’s most committed disciples began gathering at “Camp Hored” in Pearl River, New York to plan their next steps.

Then the whole project got a jumpstart in less-than-ideal circumstances.

It turns out that John Ballou Newbrough had been practicing celibacy, but only with regards to his wife. He was quite happy to be less than chaste with his dental technician, Frances Vandewater Sweet. She became pregnant and gave birth to Newbrough’s illegitimate daughter, Justine, on January 1st, 1884. When Rachel Newbrough learned about the affair three months later she was justifiably furious and kicked her husband out of the house. Newbrough and Sweet relocated to Pearl River and the project kicked into overdrive.

Throughout the summer of 1884, John Ballou Newbrough and Andrew Moore Howland traveled all over the country scouting locations for the proposed Shalam Colony. The Oahspe stated that Shalam was located in a desert, so they focused their search on the southwest. Plots in California and Arizona seemed promising, but didn’t match the geography of the sacred text. One location in Mexico seemed ideal, but was nixed because of the highly volatile political situation in the area.

In September, the duo’s wanderings took them to the Mesilla Valley of New Mexico, and a consultation with local Masons led them the perfect spot. It was some fifty miles north of El Paso, Texas; eight miles north of Las Cruces, New Mexico; and only half a mile west of the Doña Ana stop of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe railroad. On October 4th, they purchased some 1,490 acres of virgin farmland from a local rancher for $4,500.

At the end of the month, the first trainload of Faithists from the east coast arrived in Doña Ana, including Newbrough, Dr. Tanner, and Frances Vandewater Sweet. The Kingdom of Jehovih on Earth would soon be at hand.

Colony of Cranks

The Shalam Colony is easily the strangest commune I’ve read about to date.

- For starters, there were no written charter or bylaws. All decisions were guided by the precepts set forth in the Oahspe and especially the Book of Shalam.

- Only Faithists could join. Christians, Spiritualists and Theosophists were turned away unless they renounced their false gods and accepted Jehovih as the one above all.

- Just to be safe, lawyers or politicians were also barred from joining. And supposedly doctors. Exceptions must have been made for Drs. Newbrough and Tanner.

- New colonists surrendered of all of their material possessions and money, which then became communal property. No money was exchanged between colonists, who received two meals a day, bunkhouse-style lodging, a set of clean white cult robes, and medical care, all free of charge.

- All of the colonists were equal in rank, and no one was master. At least, that was the idea. In practice, there was an inner circle that ruled the colony. It included Newbrough, who made all of the decisions, and Howland, who figured out how to pay for it all. And also Frances Vandewater Sweet, who had both men wrapped around her little finger.

- Men and women were to share the workload equally, though some jobs were definitely classified as “men’s work” and others as “women’s work.” Everyone was to work five hours a day. Well, that was the goal at least, you know how farm work is.

- Meat was forbidden, and the colonists subsisted on a vegan diet. (Okay, the also ate honey, you can argue with me about that on Twitter.) The only exception they made was for the younger children, who were allowed to drink milk.

- Also forbidden: liquor and tobacco, as well as opium and all other narcotics.

- Faithists were also prohibited from joining “cliques of iniquity” and participating in “vicious trafficking.” I have no idea what either of those means.

- Shalam was to be completely self-sufficient. Once it reached that goal, the Faithists would begin gathering orphan babes and castaway infants and foundlings to raise in the manner specified by scripture.

They ran into problems almost immediately.

The plot of land Newbrough and Howland had purchased wasn’t exactly ideal for farming. The climate was arid, there was no irrigation, and the best land lay was situated next to a meander of the Rio Grande that was prone to disastrous flash flooding. It would take a lot of hard work and money to make the land productive. Howland took care of the money, but as for the hard work…

The Faithists were white-collar city slickers who didn’t know the first thing about farming. What they did have was a naive faith that Jehovih would provide both spiritual guidance and material comfort as he did for Tae and Es. They quickly proved to be indifferent farmers with little desire to improve their craft. No one really wanted to farm anyway; they were there to praise Jehovih and raise a crop of god-children.

As a result, for two years the Faithists lived in tents, drank dirty river water, and lost expensive farm implements to dumb rookie mistakes. Several Faithists in the first group of colonists died of disease and starvation that first winter.

In the end, the labor shortage was solved when Howland hired Mexican day laborers to do most of the day-to-day work around the colony. This was controversial because the Book of Shalam explicitly forbid the colony from hiring outside labor. Newbrough and Howland hoped that it would only be a temporary measure.

Over the years, the colony began to take shape as the following buildings were erected:

- A children’s home, complete with a nursery, twenty individual rooms, a kitchen and a cafeteria.

- A “Fraternum” to house the adults, built in a a Spanish mission style with forty private rooms, and later running water and baths.

- A studio for Newbrough to meditate and receive transmissions from the spirit world in private.

- And the Temple of Tae, a surprisingly small building with a common room and a library, decorated with Newbrough’s automatic paintings.

But some of those buildings lie years in the future. Let’s rewind a bit.

You may have noticed that the initial list of colonists gave at the beginning of this section did not include Andrew Moore Howland. While the other Faithists were trying (and failing) to work the land, Howland was back in Boston getting his finances in order.

By December 1885, he was ready to join his co-religionists in New Mexico. To celebrate the occasion, he gifted the land the colony was living on to the newly incorporated “Church of Tae,” on the condition that they repay the $20,000 he had already spent on the maintenance of the colony, and eliminate their need for hired labor by July 26, 1886.

This raised a few eyebrows among the other Faithists.

First, they were infuriated by the idea that Howland’s expenses needed to be repaid. Every other member of the commune had surrendered their personal property and assets when they had joined. Why did Howland need to be repaid if all of his property was going to belong to the church?

And second, they were surprised to learn that the land they lived on was not owned by a religious trust, not by their prophet Dr. Newbrough, but by a third party who was technically supposed to be their equal. As they dug into the specifics, it turned out that it wasn’t just the land — when the colonists had surrendered their possessions, they had been surrendering them to Andrew Moore Howland. He owned everything.

Some of the Faithists, led by Dr. Tanner, staged a mini-revolt against Howland’s financial tyranny, claiming that the true nature of the “commune” had been misrepresented to them. In response, Howland rescinded his gift. After a brief power struggle, Newbrough declared himself to be infallible, sided with Howland, and drove the malcontents out. The colony was reduced from 45 people to 20 people, and the inner circle was reduced to a tribunal of Newbrough, Howland, and Sweet.

Andrew Moore Howland got to keep his personal property. Which was good, because at the same time John Ballou Newbrough was losing all of his.

Rachel Turnbull Newbrough finally sued for divorce in August 1886, citing irreconcilable differences as the cause. She rejected her husband’s abstemious lifestyle, unorthodox religion, and the very idea of communal living. She also had some choice words to say about the pert little hussy he called a dental technician.

To placate his ex-wife, Newbrough surrendered all of their jointly-owned effects, as long as Rachel relinquished her claims to any share of the Shalam Colony. Their divorce was finalized on October 6, 1886 and the colony was secure, though the loss of Newbrough’s personal assets meant they were depending on Howland’s personal fortune more than ever.

He enjoyed the bachelor life for just under a year before marrying Frances Vandewater Sweet on September 28, 1887. Even though he still professed to be chaste, and Faithists were not allowed to have second marriages.

Children Wanted, No Questions Asked

Second marriages aside, 1887 did not seem like it was going to be a great year for the Shalam Colony. Membership had dwindled to its lowest point yet, with only a dozen or so colonists remaining. The farm was still nowhere close to self-sufficient, and Newbrough and Howland were tied up in the territorial courts thanks to a flurry of lawsuits filed by disgruntled former members.

And yet, at what must have seemed to be the darkest hour for the entire Faithist project, Newbrough decided the time had come for them to gather orphan babes and castoff infants and foundlings.

Their initial approach was brash and bizarre: they took out a classified ad in several New Orleans newspapers.

Wanted to adopt: a little girl and boy, from two to six years old; orphans or destitute children preferred. Apply in person or by letter to room 102, St. Charles Hotel.

When a New Orleans Times-Picayune reporter asked Newbrough about this strange and concerning ad, Newbrough gave flippant answers that insulted not only the reporter, but also New Orleans and the entire South in general. Well, that got policemen involved, and Newbrough and Howland were dragged into court. Magistrates were reassured that the two men’s intentions were honorable, and warned them that their future efforts should probably be more circumspect.

At first they didn’t get the hint. In Kansas City, a salesman looking for his clients asked the two men if they were the ones interested in buying sewer pipes. “No sir,” Howland barked, “I am here to get babies.”

Eventually, they hit on a more effective strategy. They set up receiving homes — essentially, abandoned baby drop boxes — in New Orleans, Chicago, Kansas City and Philadelphia. They were small shacks, lit by electric light at all hours of day and night, that housed comfortable bassinets and sported a large sign that read, “Children Wanted: No Questions Asked.” It was still sus, but on the plus side there weren’t two old guys in cult robes hanging out and making everything extra weird.

By the end of the year they were ready to transfer their first batch of ten infants to New Mexico, with plans to adopt five more each year. Upon arrival, the children were stripped of what little identity they had. All records of their birth parents and origins were destroyed, and they were given new, Panic names. Names like “Fiatisi,” “Hagrvalo,” “Ha’jah,” “Pathocides,” “Thale,” “Vohnu,” and “Whaga.” (It’s probably a good thing that the children didn’t go to public school, because they would have been teased mercilessly.)

And so the great experiment began.

Between 1887 and 1900 the colony took in more than fifty children, ranging from newborn babes to six year olds, both boys and girls, and representing almost every race and ethnic group in the country.

The Faithists intended to take these “babes the world would not have” and raise them to be its salvation in an environment free of racial and class distinctions, away from the commercialism and materialism and selfishness of the modern world.

The children were kept on a strict vegan diet, though the growing infants were still allowed to have fresh milk, and honey was a rare treat.

No expense was spared to educate the children. The schoolhouse was organized along the lines of a Montessori-style system, with no separation between age groups and an emphasis on learning by doing and questioning. Vocational education was provided by the colony members and supplemented with more traditional pedagogy provided by professional teachers hired from the outside world. Even though that was explicitly forbidden by the Book of Shalam.

When the children turned 14, they were given the option of leaving the community to rejoin the outside world, or remaining in the colony to help raise the next generation of foundlings.

Either way, they would be the progenitors of a new race of man, whose innate nobility and purity would spread the gospel of Faithism to the wider world.

At least, that was how it was supposed to work.

There were losses almost immediately. Of the first thirteen infants transferred to Shalam, three of them died before their first birthday. It turns it’s hard for a mere handful of women (and their maids) to take care of a bakers’ dozen worth of babies. That necessitated the hiring of more nurses. Over the years more children would be lost to disease and accident.

Newbrough also jumped the gun hiring their first batch of teachers, who arrived in the colony to discover that the children were still infants barely old enough to crawl, and that teachers were expected to do manual labor until the children were old enough to be educated. And at lower wages than the ones they had been promised. Needless to say they all quit, or were eventually evicted for failing to abide by the Faithists’ strict prohibitions against fun.

With all of the colonists’ focus on the children, the rest of the colony was even more poorly run than usual. They still hadn’t cleared more than a few acres of land and were dependent on outside sources of food. In February 1888, burglars broke into the Fraternum and destroyed an iron safe in search of Howland’s fortune. In April of that year, unknown arsonists burned down the barn containing all of the colony’s farm implements and feed, and Howland was forced to shell out several thousand dollars to replace it all.

At one point Howland was spending almost $250/day to keep the colony afloat, and that’s in 1890 money — in 2021 money, we’re talking almost $8,000. Needless to say, the colony was the victim of more than one payroll robbery over the years.

To make matters worse, Shalam had attracted a large group of hangers-on, ranging from tramps looking for work, to sincere co-religionists not yet ready for communal living, to arrogant former colonists who saw manual labor as beneath them. The colonists treated their visitors as the Oahspe directed: they gave them a hot meal and sent them on their way. All that did was create a create a semi-permanent community of leeches and parasites who knew they could always rely on the Faithists for a hot meal.

Newbrough himself started to become erratic and show signs of paranoia. In 1889 he prophesied that all of the world’s governments, religions and businesses would be overthrown in 58 years, plunging the world into anarchy. He was absolutely correct that the next half-century would be a doozy, and absolutely wrong that the children of Shalam would be the ones who would save us.

To help ease the colony’s financial burdens (and partly to distract the prophet from how dire the situation had become), Howland convinced Newbrough to prepare a second edition of the Oahspe and embark on a lecture tour to promote it. Newbrough threw himself into the task, working on astonishing new revelations that would be collected in the supplementary “Book of Graytius.”

We’ll never know what it might have contained.

A particularly virulent strain of influenza made its way through the Mesilla Valley in the early months of 1891, and the Shalam Colony was hit hard. Ten people died, including several children. And John Ballou Newbrough, who passed away on April 22, 1891.

No Trustee of the Children of Shalam

At this point you would have forgiven the Faithists of Shalam for throwing in the towel. After all, their colony had proven to be a huge money sink and might never be self-sustaining; their numbers had been reduced by schism and disease; and their prophet lay dead in a shallow grave.

Whether it was out of pure faith or just the sunk cost fallacy, Andrew Moore Howland refused to let the dream die.

At this point we should probably give a brief description of Howland — he was a short and portly man, immaculately dressed, with a short graying beard and an avuncular manner. If you can imagine Richard Attenborough in Jurassic Park, you’re 90% of the way there. Especially if you were imagining the part where his naive optimism was about to lead to a terrible, completely avoidable disaster.

It started off promisingly enough, with an invigorating legal victory. Several disgruntled colonists, led Jesse M. Ellis, had filed a lawsuit suit agains the colony in an attempt to reclaim the property they’d donated when joining, and claim wages for the work they’d put in to improve the land. It had not gone well. Ellis claimed that Newbrough and Howland had misrepresented the true nature of the colony (which they most assuredly had), and also tried to sway jurists by portraying Shalam as a den of immorality. Lower courts had awarded Ellis some $10,000 in restitution, but Howland appealed the judgment all the way to the highest court in the territory.

In 1892 the supreme court handed down its final judgment in the case of Ellis v. Newbrough. Judge Freeman’s opinion was not kind to Ellis:

It is insisted, however, that the appellee has a right to recover for a deceit practiced upon him; that he was misled by the Oahspe and other writings of the society. On the contrary, the defendants maintain that the appellee is a man who can read, and who has ordinary intelligence, and this the appellee admits. This admission precludes any inquiry as to whether appellee’s connection with the Faithists… gave evidence of such imbecility as would entitle him to maintain the suit. Admitting, therefore, that the appellee was a man of ordinary intelligence, we find nothing in the exhibits which in our opinion was calculated to mislead him.

Ellis v. Newbrough

Of course, Freeman also liberally and sarcastically quoted from the Oahspe in a way that suggested he thought both the plaintiff and defendants were, in fact, imbeciles if not outright insane. Ouch.

Once the legal status of the colony and its property was secure, Howland opened up his pocketbook even wider and poured the rest of his personal fortune into the colony. That seemed to do the trick. Within a few years the colony became a productive farm, though still not a profitable profitable one. It served nearby communities with its general store, warehouse, machine shop, and apiary. It had electric lights, hot and cold running water, and every modern amenity you could think of. Membership numbers rebounded, with up to thirty members taking care of twenty children. Infants continued to pour into the colony every year, and the older children were released into the adult world.

He worked many long nights with the prophet’s widow in a desperate attempt to hold the colony together. Eventually, sparks flew between them. Howand and Frances Vanderwater Sweet Newbrough were married on June 25, 1893. It was the bride’s third marriage, though she professed a creed that forbade having more than one.

To deal with the growing throngs of hangers-on, Howland established a separate community called Levitica. On paper, it was meant for those who supported Shalam’s goals but could not bring themselves to join a commune or accept Jehovih into their hearts. In practice, it served as a way to move the colony’s unbelievers and support staff out of the way so the Faithists could enjoy their pretend utopia without seeing constant reminders of their own inadequacy.

As the children grew older, they too joined the list of the colony’s problems.

At first, many of them refused to work in the fields as they grew older. In spite of the colony’s stated goal of raising the children in a world free of race and class distinctions, their noble intentions failed to match the children’s lived experience. To them, work was not something done by Faithists, but something done by Mexicans.

Then some of the older girls became pregnant, and ran away from the colony to marry handsome young ranch hands. The colonists were at a loss to explain how good Faithist children could do such a thing… until they discovered the ranch hands and been enticing the girls to meet them with offers of roast rabbit. Red meat, the colonists decided, was at the root of their problem.

In 1898, in a last-ditch attempt to make the colony profitable, Howland converted it to a dairy farm. (I have no idea how he was able to reconcile running a dairy with the Faithists’ strict veganism.) It was another hare-brained scheme doomed to failure. The capital and labor costs involved in running a large-scale pasteurization plant were enormous. They soon discovered that the market in Las Cruces wasn’t large enough to sustain a dairy so large. They could have easily sold their product in El Paso, but the costs of refrigeration and shipping ate up any potential profits.

By 1900, writing was on the wall as far as Shalam was concerned.

Howland was teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. Over the course of 15 years he’d liquidated all of his investments and sunk over $500,000 into the colony’s upkeep. He had no more to give.

With no money to left to hire ranch hand, the fields lay fallow and the irrigation pumps rusted away. The dairy was shuttered in August, and no one missed it.

Levitica had been gone for several years. It had never stopped being a drain on the rest of the colony, peopled by parasites who had come to take and not give. After it was shut down Howland started to redevelop the property as a sanitarium for the rich, but the spring flooding of the Rio Grande swept away all of his work.

The children were forced to go to the county’s public schools, which only made them even more rebellious.

The few remaining colonists were reduced to traveling door to door, vainly trying to sell vegetarian snacks to their neighbors. They constantly squabbled with each other, and many left for good.

In 1901, Howland filed a petition in the New Mexico courts to dissolve the Church of Tae, which was quickly granted. That allowed him to sell off some of the unused property and avoid bankruptcy.

There were some 30 children living in the colony at the time. Howland and Sweet personally adopted five of the children who they could not bear to part with. The rest were taken away from from the only life they’d ever known and dispersed to orphanages and foster homes all over the country. One, Little Thale, largely considered the brightest child in the colony, was taken in by Booker T. Washington and his wife.

The Shalam Colony closed its doors forever on November 30, 1907 when Howland sold the last piece of property to a local rancher. He used the proceeds (and a small inheritance from the estate of his cousin Hetty Green) to settle his debts and fund a modest retirement in El Paso. As a sideline, he sold vegetarian cookies made of honey and cornmeal which he called “U-Like-Ums.” (Which I assume are terrible. Because if you have to tell me that I’ll like it in the name, I can assure you that I won’t.)

Andrew Moore Howland passed away in 1917. To the end of his days he believed in the utopian vision of John Ballou Newbrough, and claimed that Shalam had only failed because devils had influenced the choice of site.

Dr. Henry Samuel Tanner died in 1918. Despite his expulsion from the colony he remained a devout Faithist and continued to advocate for the religion in his writings. (Apropos of nothing, one of these books, The Human Body: A Volume of Divine Revelations, features the following bit of disturbing doggerel on the cover: “I will write my law in their hearts, and put it in their inward parts.”)

Frances Vandewater Sweet Newbrough Howland followed her third husband to the grave in 1922. With her passing, the inner circle of Shalam was no more.

Adapting to the modern world proved to be a difficult task for the children of Shalam. Some did not handle it well, and ended up poor, homeless, or even dead in the streets. Others, especially those who were babes at the time of the colony’s dissolution, were able to resume relatively normal lives. All of them would fondly remember their time in Shalam as the best days of their lives, full of happiness and unconditional love. None of them turned out to be beings of perfect beauty and wisdom, or the seed of a new race of man.

The Oahspe itself remains in print and continues to generate converts to the faith of Jehovih. Thanks to linguistic changes “Faithism” is no longer a great name for a religion, so modern believers tend to use names like the Kosmon Church, the Kosmon Fraternity, or Kosmon Scientists. There are small groups in many cities and countries, the most prominent of which is in Brooklyn, New York.

Over the years the former Shalam Colony passed through hundreds of different owners, who found it hard to work the land because locals thought it was cursed. It did not become remotely profitable until the mid-1940s.

Today no trace of the land of children remains, save for a historical marker and a hiking trail than runs through the former property.

“Thus Jehovih’s kingdom swallowed up all things in victory; his dominion was over all, and all people dwelt in peace and liberty.” (The Book of Jehovih’s Kingdom on Earth, 26:24)

It’s easy to pinpoint why the Shalam Colony failed, because it had never been a good idea to begin with. No one involved had even the vaguest idea of how to run a farm, let alone how to clear one on the wild frontier, and they all thought themselves above manual labor. The colony had only survived as long as it had because a rich patron showed even less judgment than the colony’s founders.

The Faithists’ attempt to raise children uncorrupted by the modern world failed because the colony never managed to fully separate from the modern world. In the end, all they could give to the children was unconditional love. Which proved to be a necessary, but not sufficient, condition.

In an ironic twist, the Oahspe itself warned the Faithists of all these pitfalls. It counseled the Faithists to turn away those who wished to lead or manage but not work, and to avoid hiring outside labor. It even made it very clear what roles and skills would be needed for such a colony to succeed. In their zeal to realize their prophet’s vision, the Faithists wound up discarding or ignoring the actual content of that vision.

At some level the colonists felt confident in spite of their shortcomings because Jehovih would provide, as he did in the Book of Shalam. Now, I am not opposed to naive faith — for instance, I’m powerfully moved by the “little way” of St. Thérèse of Lisieux. But there’s naive, and then there’s naive. It’s one thing to believe that God has a plan. It’s another to insist that he’s going to personally intervene any second now while your ship slowly sinks into the briny deep.

After Newbrough’s death there were attempts to start Shalam-style communes in Alameda, California in 1892; in Fullerton, California in 1895; and in Denver, Colorado in 1902. They all failed. It turns out people are reluctant to drop off even unwanted children with crazy-eyed cultists in weird robes.

And yet Shalam remains an alluring dream. It represents the ultimate triumph of virtue over vice, of love over hate, shows us a world where good triumphs over evil with no shots fired and no morals compromised. If this is the way the world ends, well, sign me up, because it’s beautiful.

But here’s the thing about dreams, especially the beautiful ones: they always fade away when you have to wake up.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

Scam artist Ann O’Delia Diss Debar faked automatic writing and painting for her own nefarious ends. We told her story in Series Three’s “Spirit Princess.” (Of course, Dr. Newbrough’s automatic writing was totally real. Wink.)

Elizabeth Rowell Thompson, the philanthropist who fronted the money for the first printing of The Oahspe, collected free thinkers the way you or I might collect sports cards. For several years in the 1880s she also supported Dr. Cyrus Reed Teed of the Koreshan Unity, though the two eventually had a falling out. You can read all about Dr. Teed and the Koreshans in Series Four’s “We Live Inside.”

The Oahspe has continued to exert its influence over the years… though that hasn’t always been positive. For a strange example, check out the story of the Shaver Mystery (Series 11’s “A Warning to Future Man”).

Sources

- Fogarty, Robert S. All Things New: American Communes and Utopian Movements, 1860-1914. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

- Gunn, Robert A. Forty Days without Food! New York: Albert Metz & Co, 1880.

- Hartman, William C. Hartmann’s Who’s Who in Occult, Psychic, and Spiritual Realms. Jamaica, NY: Occult Press, 1925.

- Jones, J. Nelson. Thaumat-Oahspe. Melbourne: J. C. Stephens, 1912.

- Martinez, Susan B. Time of the Quickening: Prophecies for the Coming Utopian Age. Rochester, VT: Bear & Company, 2011.

- Melton, J. Gordon (ed). Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (4th ed). Detroit: Gale Research, 1996.

- Newbrough, John Ballou. The Lady of the West; or, The7 Gold Seekers. Cincinnati: Moore, Wilstach and Overend, 1855.

- Newbrough, John Ballou. A Catechism on Human Teeth. New York: S.W. Green, 1871.

- Newbrough, John Ballou. Oahspe: A New Bible in the Words of Jehovih and his Angel Embassadors. New York: Oahspe Publishing Associates, 1882.

- Newbrough, John Ballou. The Light of Kosmon. London: Kosmon Press, 1939.

- Newbrough, John Ballou. The Origin of Oahspe. London: Kosmon Press, 1939.

- Tanner, Henry S. The Human Body: A Volume of Divine Revelations. Long Beach, CA: self-published, 1908.

- Colavito, Jason. “Review of ‘The Lost Continent of Pan’ by Susan B. Martinez.” Jason Colavito, 21 Oct 2016. http://www.jasoncolavito.com/blog/review-of-the-lost-continent-of-pan-by-susan-b-martinez Accessed 8/31/2020.

- “John Ballou Newbrough.” History-Computer<>. https://history-computer.com/People/NewbroughBio.html Accessed 8/27/2020.

- “Oahspe.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oahspe:_A_New_Bible Accessed 8/27/2020.

- Ellis v. Newbrough, 6 N.M. 181 (1891)

- “Ellis vs. Newbrough et. al.” Pacific Reporter, Volume 27 (1892).

- Duino, Russell. “Utopian Theme with Variations: John Murray Spear and his Kiantone Domain.” Pennsylvania History, Volume 29, Number 2 (April 1962).

- Fogarty, Robert S. “American Communes 1865-1914.” Journal of American Studies, Volume 9. Number 2. (Aug 1975).

- Perry, Wallace. “The Glorious Land of Shalam.” Southwest Review, Volume 38, Number 1 (Winter 1953).

- Stephan, Karen H. and G. Edward. “Religion and the Survival of Utopian Communities.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, Volume 12, Number 1 (March 1973).

- Stoes, K.D. “The Land of Shalam.” New Mexico Historical Review, Volume 33, Number 1 (January 1958).

- Stoes, K.D. “The Land of Shalam (Concluded).” New Mexico Historical Review, Volume 33, Number 2 (April 1958).

- Willsky, Lydia. “The (Un)Plain Bible: New religious movements and alternative scriptures in Nineteenth-century America.” Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, Volume 17, Number 4 (May 2014).

- “Marriages.” Caledonian Mercury, 25 Feb 1860.

- “Death in dentistry.” New York Daily Herald, 21 Mar 1872.

- “The death from laughing gas.” New York Daily Herald, 31 Mar 1872.

- “The latest ghost story.” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, 29 Apr 1875.

- “Revival of Spiritualism.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 19 Aug 1875.

- “The Faithists.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 12 Apr 1882.

- “Dr. Newbrough’s ‘Oahspe.'” New York Times, 21 Oct 1882.

- “Religion with a crank.” Buffalo Weekly Express, 24 May 1883.

- “Faithists in convention.” New York Times, 25 Nov 1883.

- “Shalam.” Las Cruces (NM) Sun-News, 11 Oct 1884.

- “Sheaves from Shalam.” Santa Fe (NM) New Mexican Review, 22 Jan 1885.

- “The Faithists.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 2 Oct 1885.

- “A queer colony.” Boston Globe, 24 Jan 1886.

- “A remarkable document.” Las Vegas (NM) Gazette, 10 Mar 1886.

- “The Faithists of Shalam.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 2 May 1886.

- “The Faithists of Shalam.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 9 May 1886.

- “Notice of suit.” Las Cruces (NM) Sun-News, 21 Aug 1886.

- “Who are they?” New Orleans Times-Democrat, 24 Aug 1887.

- “Brought before mayor.” New Orleans Times-Picayune, 25 Aug 1887.

- “Territorial topics.” Santa Fe New Mexican, 24 Apr 1888.

- “Shalam exposed.” El Paso Times, 2 Dec 1888.

- “A colony of philosophers.” Carlsbad (NM) Current-Argus, 29 Mar 1891.

- “A noted Spiritualist.” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, 23 Apr 1891.

- “A new religion and new people.” Pittsburg Dispatch, 26 Apr 1892.

- “Nothing but verses.” San Francisco Examiner, 17 Sep 1892.

- “On to Shalam.” Boston Globe, 1 Apr 1893.

- “Shalam’s colony.” Santa Fe New Mexican, 20 May 1893.

- “The colony of Shalam.” Waterloo (IA) Courier, 15 Mar 1895.

- “Colony of freaks.” Santa Fe New Mexican, 21 Mar 1895.

- Warren, Harry A. “With Faithists in Santa Ana valley.” Los Angeles Herald, 14 Jul 1895.

- Warren, Harry A. “Another day with the Faithist Clan.” Los Angeles Herald, 15 Jul 1895.

- Warren, Harry A. “The philosopher Thales.” Los Angeles Herald, 16 Jul 1895.

- Warren, Harry A. “The Faithists betrayed.” Los Angeles Herald, 17 Jul 1895.

- Warren, Harry A. “Bible of the Faithists.” Los Angeles Herald, 19 Jul 1895.

- “Trouble at Shalam.” El Paso Herald, 11 Dec 1896.

- “Shalam and its prophet.” Kansas City (MO) Star, 1 May 1897.

- “Shalam, the Land of Children.” Philadelphia Times, 15 Aug 1897.

- Parks, Lafayette. “A new race.” Girard (KS) Appeal to Reason, 6 Aug 1898.

- “End of the Shalam colony.” Washington (DC) Times, 29 Apr 1901.

- “Shalem to become a sanitarium.” Boston Post, 5 May 1901.

- “A new religion.” Jackson (MI) Daily News, 21 Nov 1902.

- “Brotherly love and bathtubs.” Buffalo Evening News, 31 Jan 1907.

- “Himalawowoaganapapaland.” New York Sun, 20 Jan 1907.

- “Failure of a religious sect.” El Paso Herald, 30 Nov 1907.

- “Interest growing at Spiritual congress.” Long Beach (CA) Press, 18 Aug 1911.

- “Gideon Howland’s 408 heirs.” Boston Globe, 30 Jul 1916.

- “Estate to go to 438 heirs, local people to get shares.” Oakland Tribune, 25 Jan 1917.

- “Howland dies; Shalem pioneer.” El Paso Herald, 10 Apr 1917.

- “Children of the Kosmon Dawn.” Cincinnati Enquirer, 20 Oct 1921.

- Martin, G.A. “Mrs. Frances Howland, widow of Shalem colony founder, is dead; colony was notable.” El Paso Herald, 5 Jan 1922.

- Mead, Phil. “Shalam colony now only crumbling buildings.” El Paso Times, 23 Apr 1955.

- Priestley, Lee. “Shalam: ruined utopia.” Las Cruces (NM) Sun-News, 4 Jul 1976.

- Kestenbaum, Sam. “A Forgotten Religion Gets a Second Chance in Brooklyn.” New York Times, 7 Jun 2018.

Links

- Oahspe Standard Edition

- Thaumat-Oahspe

- International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals

- Shalem Colony Trail

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: