Rapscallions!

"surprised and excited"

Okay, here’s what you need to know from previous episodes.

In the final years of the American Civil War, it became obvious to the Confederacy that it could not win by conventional means. It became desperate to find something that could change that outcome, and increasingly turned to cloak-and-dagger strategies: sabotage, subterfuge, and terror.

Eventually the Confederates established a spy ring in Canada run by three men: money man Jacob Thompson, James Buchanan’s former Secretary of the Interior; charming Clement Claiborne Clay, former Senator from Alabama; and reliable James P. Holcombe, the man who could actually get things done. For an entire year they kickstarted countless audacious and outrageous schemes.

We’ve previously discussed attempts to free Confederate POWs being held far behind battle lines; arming Copperheads in the Northwest and encouraging them to secede from the Union; and repeatedly trying to capture or destroy the only warship on the Great Lakes. This time, we’re wrapping up with a grab bag of less ambitious plots, most of them failures, all of them fascinating.

“Not Anxious For Peace”

Though there were three Confederate spymasters in Canada, they were not united in purpose. Former Alabama Senator Clement Claiborne Clay had frequent disagreements with Jacob Thompson and James Holcombe over which operations they should fund and how much.

When Clay fell ill, he decided to take his leave from the others and recuperate at St. Catherine’s, in the Niagara region of Ontario. That was when he met George Sanders.

No, not the famous essayist and novelist who wrote Lincoln in the Bardo. This George Sanders was a shadowy figure who had spent decades lurking around the fringes of politics as a fixer and lobbyist.

In the early 1840s Sanders attempted to persuade President Tyler to annex the Republic of Texas. In the late 1840s he represented the interests of the Hudson’s Bay Company in Oregon. In the 1850s he was he United States Consul in Liverpool, until he was fired for his utter lack of tact and for openly advocating for the assassination of European monarchs like Napoleon III.

When the Civil War started, Sanders took up residence at the Clifton House in Niagara Falls, Ontario and began presenting himself as a representative of the Confederate government. He was not, but he was funneling private money to Confederate sympathizers, expatriates, and operatives in Canada.

Sanders’ schemes often overlapped and interfered with those of Thompson, Clay, and Holcombe. Since he was in the area, Clay went to give Sanders a stern talking-to. Instead, the two men wound up charmed by each other and decided to join forces. Their first big plan was to influence the 1864 presidential election by opening up fake peace talks.

One slight problem was that Clay and Sanders did not have any access to official diplomatic channels. So they had to get creative.

Enter Colorado Jewett.

William Cornell Jewett was a banker; well, I say banker but he seems to have been more of a serial embezzler and self-promoter. He popped up in Denver in 1860, where he appointed himself Colorado’s “special representative” despite having never visited the territory before.

He became widely known as William “Colorado” Jewett, though the people of Colorado did not actually seem to like him. The Western Mountaineer said he suffered from “diarrhoea of words and constipation of ideas.” The Rocky Mountain News called him “William ‘Crazy’ Jewett.” His received better coverage from newspapers outside the territory, because he was witty and they didn’t know he was full of crap.

When the Civil War broke out Jewett became an advocate for peace. He spent the better part of three years steaming back and forth across the Atlantic, trying to find a country willing to mediate between North and South. He had no official government backing, because everyone in the government hated him. Attorney General Edward Bates called him a “crack-brained simpleton” and the rest of the cabinet liked him even less. Even reliable anti-war politicians like Clement Laird Vallandigham refused to back Jewett’s schemes because they did not believe the war should be resolved by outside mediators.

That’s okay. Jewett didn’t actually want to succeed. He just wanted the publicity.

He eventually took up residence in Canada, where he became enormously popular by telling the Canadian public exactly what it wanted to hear. For instance, he repeatedly promised that the United States would abandon all of its territorial claims to Canada, though he had no ability to make good on that promise. Canadians either did not know or did not care.

In June 1864 Clay and Sanders approached Jewett, claiming to be Confederate ambassadors authorized to negotiate a peace treaty, and asked him to send word to Washington.

Clay and Sanders made this move without the blessing of Thompson and Holcombe, who thought it was foolish to unnecessarily reveal their presence in Canada. (Their caution was commendable, but the Union had always known about their operation.)

Jewett was all-in, but he had no way to communicate with the government either. He had a bad habit of pestering the White House with lengthy blathering telegrams, and these days that correspondence went right into the circular file. So Jewett reached out to the one friend he had left: Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune. He related Clay and Sanders’ offer, but may have oversold it a bit, claiming the Confederates had “full and complete” powers to negotiate a peace treaty. Which they did not have, at all.

Greeley had already been yelled at by the administration for pretending to be a diplomat, but he too was desperate for peace at any cost. He wrote a passionate letter to Lincoln asking him to take Jewett’s proposal seriously. Here’s an edited version of that letter, read by the inimitable Eric Leslie.

My Dear Sir:

I venture to inclose you a letter and telegraphic dispatch that I received yesterday from our irrepressible friend, Colorado Jewett, at Niagara Falls. I think they deserve attention. Of course, I do no indorse Jewett’s positive averment that his friends at the Falls have “full powers” from [Jefferson Davis], though I do not doubt that he thinks they have. I let that statement stand as simply evidencing the anxiety of the Confederates everywhere for peace. So much is beyond doubt.

And thereupon I venture to remind you that our bleeding, bankrupt, almost dying country also longs for peace — shudders at the prospect of fresh conscriptions, of further wholesale devastations, and of new rivers of human blood. And a wide-spread conviction that the Government and its prominent supporters are not anxious for Peace, and do not improve proffered opportunities to achieve it, is doing great harm now, and is morally certain, unless removed, to do far greater in the approaching Elections.

It is not enough that we anxiously desire a true and lasting peace; we ought to demonstrate and establish the truth beyond cavil. The fact that A. H. Stephens was not permitted, a year ago, to visit and confer with the authorities at Washington, has done harms, which the tone of the late National Convention at Baltimore is not calculated to counteract.

I entreat you, in your own time and manner, to submit overtures for pacification to the Southern insurgents which the impartial must pronounce frank and generous. If only with a view to the momentous Election soon to occur in North Carolina, and of the Draft to be enforced in the Free States, this should be done at once.

I would give the safe conduct required by the Rebel envoys at Niagara, upon their parole to avoid observation and to refrain from all communication with their sympathizers in the loyal States; but you may see reasons for declining it. But, whether through them or otherwise, do not, I entreat you, fail to make the Southern people comprehend that you and all of us are anxious for peace, and prepared to grant liberal terms…

Mr. President, I fear you do not realize how intently the People desire any Peace consistent with the National integrity and honor, and how joyously they would hail its achievement and bless its authors. With U. S. Stocks worth but forty cents, in gold, per dollars, and drafting about to commence on the third million of Union soldiers, can this be wondered at?

I do not say that a just Peace is now attainable, though I believe it to be so. But I do say that a frank offer by you to the insurgents of terms which the impartial will say ought to be accepted, will, at the worst, prove an immense and sorely-needed advantage to the National cause: it may save us from a Northern insurrection.

Yours truly,

Horace Greeley

Now, Lincoln was not stupid. He immediately saw the trap that had been set for him.

These days we think of Lincoln’s reelection as an inevitability, but that is only with the benefit of hindsight. At the time he seemed extremely vulnerable: no president had been elected to a second term since Andrew Jackson, and no incumbent president had even been renominated since Martin Van Buren. He also faced stiff opposition from Democrats as well as internal challenges from Radical Republicans.

If Lincoln refused to meet with the Confederate ambassadors, Peace Democrats would attack him for being a warmonger. If he did meet with the Confederate ambassadors, Radical Republicans would attack him for being weak and hypocritical. If the negotiations broke down McClellan Democrats would attack him for being ineffective. If they succeeded there was little chance a treaty would be approved by the Senate.

Almost every path led to some sort of defeat or setback. There was only one way out: to turn the trap back on the Confederates.

Lincoln wrote to Greeley and said he was willing to meet with the ambassadors on two conditions: first, they needed to have full authorization to negotiate a peace treaty, in writing; and second, that negotiations could not begin until all parties agreed that the foundation for peace must be the full restoration of the Union and the abolition of slavery.

Lincoln knew that the Confederates would never agree to his terms. Greeley also knew that, but felt obligated to try anyway. He wrote to Jewett that the president had given him a resounding “maybe.”

Clay and Sanders decided that was an encouraging sign and asked for safe passage to Washington. Greeley just told them to wait at Niagara Falls and the government would send someone to meet them. He seemed to have a naive hope that once all of the interested parties were in the same room everything would just sort of work itself out.

Lincoln did actually send someone, his personal secretary John Hay. Hay read a letter reiterating Lincoln’s conditions for meeting with the ambassadors and then left without waiting for a response.

The “Niagara Falls Peace Conference” was over.

Clay and Sanders tried to spring the trap anyway. They leaked the existence of the Peace Conference to the press, trying to paint the Southerners as level-headed and honorable men and Lincoln as an extremist more interested in the lives of slaves than in the lives of Northern whites. Most newspapers identified the story as obvious propaganda and did not make a big deal out of it. Since there was no ongoing element the story, it quickly dropped out of the news cycle.

That was that.

“Vairmont Yankee Scare Party”

Clay and Sanders began focusing on a new plan: cross-border raids. They believed small commando units could slip across the border and target nearby towns where they could destroy factories, rail lines, and communications infrastructure; maybe rob a few banks, burn a few farms, and raise a little hell while they were at it.

Jacob Thompson was dead set against it. He was still somewhat uncomfortable with operations that targeted civilians, but more importantly he realized any raid would be an international incident that violated Britain’s neutrality. That would inevitably lead to a crackdown on the entire Canadian operation.

What Thompson failed to realize was that creating an international incident was the entire plan. Clay and Sanders believed that when push came to shove the British would choose to side with the Confederates, in spite of several years of diplomatic efforts that suggested the exact opposite. It was that sort of thinking that had Thomas Henry Hines wondering if Sanders was a Union double agent trying to take down their operation from the inside.

On July 16, 1864 a Capt. William Collins and his two assistants, Jones and Philips, rode into the border town of Calais, Maine. Their plan was to do some raiding and then burn the town to the ground, but word of the operation had leaked out. The raiders began the first part of their operation, robbing the Calais National Bank, and were surprised when the bank president and tellers drew guns and began opening fire. They fled outside into the arms of the sheriff and his deputies, who had surrounded the bank.

During interrogation Jones confessed that the raid was the first of several diversions, intended to lure the Maine militia away from the coast to make way for an invasion by sea. It sounded like an tall tale, except Jones also gave up the locations of several weapon caches and that intelligence proved to be accurate.

Well. That could have gone better. Clay and Sanders decided to try again, and do it right this time. They tapped Lt. Bennett Henderson Young to lead the operation.

Bennett Henderson Young was a college student from Nicholasville, Kentucky when the war broke out. Originally indifferent to the conflict, he joined the Confederate army after Union soldiers raped and killed his fiancée and eventually wound up in John Hunt Morgan’s Kentucky Cavalry. He participated in Morgan’s raid, was captured, escaped from Camp Douglas, and made his way to Toronto. There he enrolled in Kings College and made the acquaintance of John Holcombe, who re-introduced him to Capt. Thomas Henry Hines, who recruited him into the secret service.

Young served mostly as a courier and messenger. He delivered money to Copperheads. He helped John Yates Beall scout out Sandusky. He was one of the sixty men who went to Chicago as part of the Great Northwestern Conspiracy, and was one of the men who chose to return to Canada.

Thompson was furious with Young and the other returnees, and threatened to punish them as deserters. That eventually led Young to drift away from Thompson and Hines and fall into the orbit of Clay and Sanders, who asked him to lead their next raid.

Young was thorough and studious. After careful deliberation he chose St. Albans, Vermont as his target. It was close to the border and largely undefended, and had a centralized business district that would make it easy to create maximum chaos in a short amount of time. It was a key rail junction connecting Montreal to New York City, home to a factory that built rail cars, and the headquarters of the Vermont Central Railroad. It also had symbolic significance as the hometown of Vermont Governor John G. Smith. And if the raid went well, raiders could also hit several other towns as they made their way back to the Canadian border.

Young assembled a group of twenty men, none of them older than twenty-five, many of them escaped prisoners-of-war, former members of Morgan’s Raiders, and participants in the Great Northwestern Conspiracy. Officially they were the Fifth Company of CSA Retributors. Unofficially they called themselves “The Vairmont Yankee Scare Party.”

On October 15 the Retributors began filtering into St. Albans in groups of two and three. Their cover story was that they were members of a Montreal hunting club on their annual fall outing, not that anyone asked or cared. They spent the next few days casing the town to pinpoint the location of high value targets like livery stables, industrial facilities, and banks. Young even managed to get a guided tour of the governor’s residence from the First Lady herself.

Young had originally intended to launch the raid on Tuesday, October 18 but soon realized that was market day. The town square would be crowded, and the more civilians there were the harder they would be to control. He called an audible and rescheduled everything for October 19. Not only would the crowds be gone, many of the town’s leading citizens would be in Montpelier either petitioning the legislature or waiting to hear the latest state Supreme Court decisions.

At noon the Retributors met for lunch to make their final preparations and to arm themselves with revolvers and Greek fire. Several of them used the opportunity to get good and drunk.

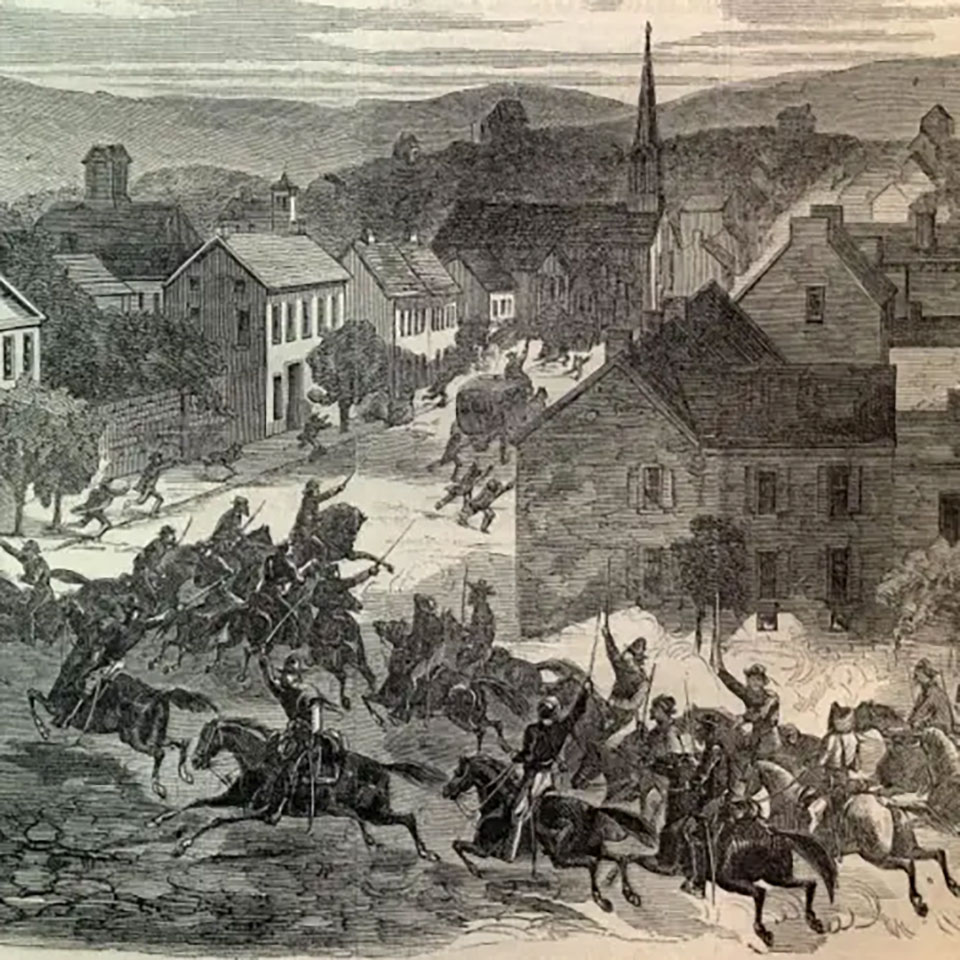

At 3:00 PM Young threw a flask of Greek fire into the washroom of the American Hotel, where he was staying. As the flames billowed behind him he dramatically strode out the front door and into the town square, drew his revolvers, and shouted, “This city is now in the possession of the Confederate States of America.” The townsfolk laughed, thinking it was some sort of joke, until the other Confederates drew their guns and started herding them into the town square, shooting two or three people when they resisted.

The Retributors’ official orders were to burn the town and destroy its rail infrastructure, with all other activities to take lower priority. They had other ideas.

They split into smaller groups. One stayed behind to guard the hostages in the town square. Three watched the streets. Four went to round up horses for their escape. Twelve of them went to rob banks.

At the First National Bank the Retributors flashed their guns and their leader declared, “If you offer any resistance I will shoot you dead. You are my prisoner.” They grabbed all that they could, but became frustrated when several money bags they cut open turned out to be full of pennies. They abandoned the bags, not realizing that at least one of them was full of gold coins. As they left a customer coming into the bank realized what was happening and tried to stop them, only to get a gun shoved in his face. He was marched back to the town square and put with the other hostages.

At the St. Albans Bank, the leader shouted, “We are Confederate soldiers and you are my prisoner. We have come to give you a taste of Sherman’s idea of war.” Bank president Cyrus Bishop tried to resist but was quickly overpowered, then made to swear a loyalty oath to the Confederacy. The raiders were just as sloppy as the ones at the First National Bank, taking only banknotes and bonds and leaving behind bar silver, bags of gold coins, and uncut sheets of bills and bearer bonds worth tens of thousands of dollars.

The raiders who hit the Franklin City Bank were just as disorganized but far more cruel. Before leaving they forced the tellers and customers into the vault and said they would bake to death as the town burned around them. Then they locked the vault and left. (They did leave the key in the lock, though. No one was hurt, though several of them had panic attacks.)

Outside the banks the situation was deteriorating quickly. The raiders rounding up horses shot a man who tried to stop them, and he was only saved because the bullet struck his silver pocket watch. A second civilian somehow did not hear Young’s instructions to stop and got a bullet in the spine for his troubles. A third pulled out a hidden gun and tried to shoot Young only to freak out and run away when it misfired.

Contractor Elinus Morrison heard news of the fracas, ran down to the town square to help, and got shot in the stomach for his civic-mindedness. He died a few days later, the only fatality of the raid and the northernmost casualty of the Civil War. (Ironically, Morrison was a Confederate sympathizer.)

Young realized he was losing control of the situation and decided it was time to skedaddle. The Retributors mounted their stolen horses and shouted, “We’re coming back and we’ll burn every damned town in the state of Vermont!” Then they rode out of town, shooting at anyone who got in their way and tossing flasks of Greek Fire every which way. The townsfolk finally showed some nerve, firing on the raiders as they fled. Three of the Confederates and two civilians were injured in the crossfire.

The Confederates left behind a proclamation which Young had intended to read to the hostages. The railroad conductor who found it later described it as “a highfalutin’ address to the people of Vermont, in the style of Southern chivalry.”

Fortunately, the raiders’ attempt to burn the town failed. It had been raining non-stop for several days so the buildings were completely soaked. It also turned out that the Confederates’ much-vaunted Greek fire did not work as advertised. It often did not ignite, it did not burn hot, it did not spread rapidly, and it could be extinguished just as easily (if not easier than) a normal fire. The American Hotel washroom, which Young had set ablaze, burned for most of a day but the fire did not spread to the rest of the structure and no real damage was done.

The other part of the raid was more successful. The Retributors rode out of town with about $213,000 (about $4,000,000 in 2024 money). The entire operation had taken about half an hour.

The state of Vermont was thrown into an uproar. Within 24 hours all transportation into, out of, and through the state had been locked down. Friendly militia companies began streaming in from neighboring states to help hunt down the raiders.

Too little, too late.

Turning back the clock, the good people of St. Albans quickly assembled a posse under the command of Capt. George Conger and began pursuing the Confederates. It wasn’t too hard to find them. As mentioned before, it had been raining non-stop for several days and muddy roads made their tracks easily visible. It did not help that they were leaving a Hansel-and-Gretel trail of loose banknotes and bonds in the bushes behind them.

The adverse road conditions were slowing down the raiders, so they decided to skip their second target, the town of Swanton. They did mug a farmer and swap one of their tired nags for his fast-looking horse. It also helped slow their pursuit; when the posse arrived all they saw was a butternut with a stolen horse and they wasted time chasing him down.

They soon arrived at their third target, the town of Sheldon, only to discover that the bank was now closed for the day and there was no obvious way in. Conscious that the posse was drawing ever-nearer, they threw Greek fire everywhere and rode on. There was no significant damage.

On the road to Shelburne they were delayed by a hay wagon crossing the only bridge across the river. That delay allowed the posse to catch up, and a firefight ensured. Eventually the raiders rushed the bridge, pushed the hay wagon back on it and set fire to it. The bridge was seriously damaged and the posse had to circle back to find another ford.

At 9:00 PM the Retributors reached the border, abandoned their horses, and proceeded on foot to the nearby town of Freligsburg.

The posse was not far behind. Shortly after crossing the border, they realized they were in a legal gray area and turned back to debate their next move. Their minds were made up for them when they received orders from General John Dix to pursue the raiders into Canada and “destroy them.”

(As we’ve seen in the previous episode, General Dix was a bit gung-ho about this sort of thing. Lincoln countermanded the order as soon as he learned about it… but that information wouldn’t reach Vermont for a while.)

Meanwhile, Governor-General Monck of Canada had received a telegram from Governor Smith asking for assistance. He sent police magistrates to Freligsburg to help capture the raiders.

Within 48 hours most of the Fifth Company of CSA Retributors had been rounded up and taken into custody. Two were arrested as they slept at a hotel in Freligsburg, and four more at hotels in nearby Stanbridge. Another was fished out of the gutter outside town, having collapsed in the mud. Three were plucked from railway stations as they tried to make their way to Waterloo. Two more were captured as they slept in a hayloft after burying their share of loot in a nearby corn field.

Young had separated from the other raiders, supposedly to find a doctor to care for a young comrade who had been wounded during their escape. When he learned that his men had been captured he made up his mind to find the authorities and give himself up. Or at least, that was the plan. He stopped for the night at a farmhouse, but the farmer turned him in. Capt. Conger’s search party burst in on Young as he slept and seized him before he could grab his pistols, then beat him mercilessly.

Young was tossed in the back of an wagon and a thick rope tied around his neck. When he realized that the wagon was heading back towards Vermont he began screaming that this was a violation of British neutrality, but his captors didn’t care. Desperate to escape a lynching, Young kicked Conger in the gut, shoved him off the side of the wagon, and seized the reins. The posse quickly caught up to Young and were about to lynch him on the spot when British authorities showed up and forcibly took custody of the prisoner.

One more raider was picked up in Montreal some four days later, on October 24. All in all, some 14 of the raiders were arrested and about a third of the stolen money (some $88,000) was recovered. The rest of the men and money disappeared without a trace.

On October 22 the captives were turned over to the custody of British authorities. They were arraigned before Judge Charles-Joseph Coursol on October 24, and shortly after he moved the trial to Montreal. The stolen money was placed in the custody of Guillame Lamothe, the chief of police.

It turns out the good people of Montreal loved the Confederate States of America. There were a couple of reasons: they thought the Confederates were dashing; they liked an underdog; and they really liked the idea of rebels rising up and throwing off their oppressors for some reason. It didn’t help that they didn’t think the Civil War was primarily about slavery.

The Quebecois lavished attention on the Retributors as if they were conquering heroes and not common criminals. They were given luxurious private apartments in the jail, met with VIPs and visiting dignitaries, and feasted on fried chicken and fine wine every night.

Clay and Sanders were, uh, not super happy. The Retributors were supposed to have been inflicting serious damage to the North’s infrastructure. Instead they had stolen a few hundred thousand dollars from Yankee banks. Still, the two men bit their tongues and put together the best defense team blood money could buy.

The defense’s first move was to get the case dismissed on jurisdictional grounds, claiming that a Canadian court could not try acts that had happened in the United States. Judge Coursol denied the motion, on the grounds that this would have to be decided at trial.

Meanwhile, the American consul persuaded the prosecution to pare down the case to two specific charges: a charge of assault against Cyrus Bishop, the president of the St. Albans Bank, and theft of his property.

The key questions of the trial boiled down to the following:

- Were the raiders common criminals subject to regular criminal justice, or soldiers subject to military justice?

- If they were soldiers, were orders targeting civilians valid under the rules of warfare?

- And finally, had the Yankees violated British neutrality by chasing the raiders across the border?

The opinion of the United States and the prosecution in these matters was simple.

- The Confederacy was not a separate sovereign state, and therefore Confederate commerce raiders were just common criminals.

- The Fifth Company of CSA Retributors was not a duly constituted unit of the Confederate army, and they witnesses who would testify that the raiders had not been wearing uniforms. (Though the raiders said otherwise.)

- Even if the Retributors were duly constituted, orders targeting civilians were not valid under the rules of warfare.

- Finally, they argued that the Webster-Ashburton Treaty gave them the authority to pursue criminals and rebels across international borders in exigent circumstances.

The Confederate strategy was to delay, delay, delay. Here’s a perfect example: they spent over a day arguing about whether the St. Albans Bank was a real bank. Eventually they were able to persuade Judge Coursol to recess the trial for a month, so they could get documentation from the Confederate government proving that they were soldiers. It took them the entire month, but they got it.

During the trial and the delay Young taunted the citizens of St. Albans. He wrote a letter to the St. Albans Messenger asking for copies of the paper to be sent to his jail cell, because “your editorials furnish considerable amusement to me and my comrades.” He tried to pay his bill at the American Hotel with a stolen $5 bill, then asked the manager to send him a shirt and a bottle of whiskey he’d left in his hotel room. It was masterful trolling.

The trial resumed on December 13, and Judge Coursol deliberated for less than an hour before rubber-stamping the Confederate defense. He ruled that the charges were un-prosecutable in Canada as no warrant to authorize the arrest had been issued. The raiders were set free on the spot and Guillame Lamothe handed back their stolen booty as they left the courtroom.

(At this point a rift developed between Cole and Young. After the acquittal Cole apparently scolded the raiders for not focusing on infrastructure and demanded they turn over the stolen money to him. Young and the raiders refused and kept it for themselves.)

The United States government was angry, and intimated that Coursol and Lamothe had been paid off. There was no actual evidence of wrongdoing, but Coursol and Lamothe had been awfully chummy with the Confederates outside of court and were officially rebuked for creating the appearance of impropriety.

Because of these irregularities, the British felt obliged to give the United States a re-do. The Americans filed a second set of charges for assault and robbery on Samuel Breck, the citizen who had been mugged outside the St. Albans Bank. It was a deliberate change of strategy; they believed that by focusing on an obvious criminal act like assault they could make an easy case for extradition.

Mind you, they had a hell of a time finding someone who would take the case. Judges in Montreal refused to issue warrants, because doing so would be seen as a personal rebuke of the well-liked Coursol. Eventually they found one who would, but then Lamothe refused to execute the warrant. They went over his head to one of the high constables, and then forced Lamothe to resign.

The delay allowed nine of the defendants to disappear without a trace. (There are romantic stories of them being smuggled to the west by voyageurs, but for the purposes of this story we don’t really care.) Five of them were still hanging around town, including Young, and they were dragged back to jail.

During the second trial, it slipped out that Young had been residing in Canada for years and had actively planned the St. Alban’s raid in St. Catherine’s. That changed the question from whether the Yankees had violated British neutrality to whether the Confederates had violated British neutrality. British authorities were incensed, but local Canadian authorities seemed not to care.

As in the previous trial, the Confederates were granted a one month delay to get their documents in order. When the trial resumed on February 10, 1865 it did not take long for the judge to rule that the St. Albans raid had been a legitimate military operation and therefore beyond Canadian jurisdiction. The raiders were set free… only to be immediately rearrested on a third set of charges.

This trial, though, just sort of fizzled out after Lincoln’s assassination two months later. Young remained locked up in jail until November 1865, when a sympathetic local paid off his $20,000 bond.

After the war the British government reconsidered what they happened and tried to make restitution. They paid $80,000 to the banks of St. Albans — less than half of the amount that had been stolen, and not even the whole amount that had been returned to the raiders after the first trial.

That’s better than nothing, I suppose. But not by much.

“Only A Joke”

As November 8 1864 drew closer, the Confederates desperately searched for a way to influence the election. They had tried the easy way — insinuating their propaganda into Northern papers — and it had failed. Now they were considering more extreme methods of suppressing voter turnout. How extreme? Well…

Lt. Col. Robert Martin and Lt. John Headley, two former members of Morgan’s Raiders who had also participated in the Great Northwestern Conspiracy, came up with a plan to strike at New York. They would use Greek fire to burn hotels throughout the city, which would force panicked citizens into streets already packed with drunken voters. While first responders were distracted by the chaos Copperheads would attack City Hall, police headquarters, and other strategic locations. Then they could turn their attention to freeing Confederate prisoners being held at Fort Lafayette.

Martin and Headley put together a team of eight operatives, who slowly filtered into New York at the beginning of November and spent a few days scouting potential targets. Local Copperheads provided logistical support: piano store owner Larry McDonald held onto their luggage and passed along messages, while newspaper editor James McMasters put them in touch with a local chemist who could make Greek fire and coordinated operations involving former Sons of Liberty. The saboteurs met every few days to compare notes, always in large public spaces like Central Park where they could disappear into the crowd if approached.

Headley was given the responsibility of picking up the Greek fire. He went to McMasters’ chemist, gave the passphrase (“Captain Longuemare has sent for his valise”), and was surprised to be handed a gigantic steamer trunk. I don’t know why he was surprised, because how else are you supposed to carry twelve dozen flasks of a highly volatile chemical? He laboriously hauled the trunk back to his hotel, even though it was so heavy he had to stop every ten feet to huff and puff. Eventually he hopped on an omnibus, where he realized that the case was now reeking like rotten eggs. That suggested a spill, which worried him because Greek fire was supposed to ignite as soon as it came into contact with air. He quickly got back off the omnibus and somehow made it back to his hotel room undetected.

Unfortunately for the Confederates, the Union had been warned by their double agents that something was up. They sent General Benjamin Butler and some 10,000 troops to guard key areas of the city during the election.

As you might expect, the local Copperheads took this as their cue to chicken out. What you might not expect was that the Confederates chickened out too, because Butler had decided to set up his headquarters in Martin and Headley’s hotel. On the floor right beneath them.

Martin and Headley tried to reschedule the operation several times, but the damn troops just wouldn’t leave and eventually the local Copperheads refused to participate at all because Election Day was long past and they just didn’t see the point any more.

When Butler and his men finally left town, the Confederates decided to go it alone on November 25. Not only was it the day after Thanksgiving, it was a local holiday called “Evacuation Day” celebrating the British withdrawal from Manhattan during the Revolutionary War. The double holiday meant emergency responders would have their hands full with crowds of drunk revelers.

The Confederates met that morning to divvy up the Greek fire and discuss the final plan — well, most of them did. Two of them chickened out at the last second, reducing their total number to six. The rest went over the plan: set off the bombs at hotels, shipyards, lumberyards, or anywhere they could across the center of the city to spread terror and panic. Nothing was to be hit before 8 PM, to guarantee that folks would be up and alert and minimize the loss of life.

As they parted company, one of them quipped, “We’ll make a spoon, or spoil a horn.” I have no idea what the heck that means, but it sounds cool and folksy.

Headley personally hit the Astor House, the City Hotel, and the Everett House. At the United States Hotel, one of his bombs went off prematurely and he tried to make a run for it. When the concierge tried to stop him from leaving he worried that he had been rumbled, only to eventually realize the poor schmuck was just trying to get him to turn over his key before he left.

He wandered over to the North River Wharf and tossed Greek fire at the ships tied up there. His next target was supposed to be City Hall, but by now the streets were full of panicked bystanders and he couldn’t get anywhere close. Instead he decided to double back and check on his handiwork. On the way he bumped into his co-conspirator, Robert Cobb Kennedy.

Kennedy was a Georgia boy who had flunked out of West Point, then signed up for the Louisiana infantry at the start of the war. He was wounded at Shiloh, served with Gen. Morgan but somehow escaped, only to later get captured at Chattanooga and sent to Johnson’s Island. Only twelve men ever managed to escape from Johnson’s Island, and Cobb was one of them. On October 4, just six weeks before the New York operation, he scaled the prison walls with a crude homemade rope and made it to the mainland on a stolen skiff. His escape was not noticed for a week, because his cellmate just answered for him when the guards did their roll call. (Seriously.)

Headley and Kennedy hugged, compared notes, and wandered down Broadway to see how the rest of their crew had done.

Kennedy had been set fire to Lovejoy’s, the Tammany, and the New England House. That left him with an extra bomb, so he decided to have a beer and think about his next target. On the way he passed P.T. Barnum’s American Museum and threw the bomb inside, just for giggles. Martin had hit the Hoffman House, the Fifth Avenue Hotel, and the St. Denis. The other three had set fire to the St. Nicholas, the St. James, Niblo’s Garden Theater, the Belmont Hotel, the Albemarle, the Bancroft, the Metropolitan, and the LaFarge.

They were disappointed in the outcome, though. It should have been clear from previous operations that the Confederacy’s Greek fire did not work as advertised: it was neither hotter nor harder to put out than regular fire, and sometimes it just plain didn’t work. That was the case here, too.

The United States Hotel and the Bancroft were destroyed. The St. James, Albemarle, and Fifth Avenue Hotels were seriously damaged. The first two floors of the New England Hotel were destroyed. Down at the wharf two barges were destroyed and two others damaged. But that was about it. The other buildings, including Barnum’s Museum, suffered only minor cosmetic damage. (Though it would actually burn down about eight months later — cue The Greatest Showman soundtrack in your head here.) The other blazes were put out easily, and the total damage was only $422,000 with no loss of life or even serious injury.

(Here’s the other interesting anecdote from that evening. The Winter Garden theater was hosting a benefit performance of Julius Caesar to raise funds for a statue of Shakespeare in Central Park. When smoke began streaming into the theater from the adjacent LaFarge Hotel, the crowd began to panic. Fortunately the headliner was the greatest actor of his age, Edwin Thomas Booth, and he quickly managed to calm the crowd with the assistance of his co-stars… his brothers Junius Brutus Booth, Jr. and John Wilkes Booth. Yes, really.)

The following day the Confederates retired to a Madison Square saloon to figure out what had gone wrong, and were then shocked to see their names and descriptions plastered on the front page of every newspaper. It turns out our old friend Godfrey Hyams had given the authorities very detailed information about the operation, but even without his aid the Confederates had hardly made themselves inconspicuous. Federal detectives had also found several unexploded bottles of Greek fire and pieced together correspondence from torn scraps of paper.

The conspirators needed to figure out their next course of action. First they headed for McMasters’ offices at the Freeman’s Journal, but turned around fast when they saw him getting arrested. They hurried over to McDonald’s piano store to pick up their luggage, only to be warned by his daughter Katie that detectives were waiting for them.

There was nothing left but to get out of Dodge, as fast as possible. The Confederates bought train tickets to Canada and somehow managed to slip out of town, even though every train car was being searched top-to-bottom.

Even though their names and faces were now well-known to the authorities and there was a $5,000 bounty on their heads, Martin, Headley and many of their cronies crossed back into the country a few weeks later. In early December they attempted to rescue some Confederate generals being transferred between prisons by derailing their train outside Buffalo, New York. The plan failed spectacularly, but we already covered it and the fallout from it in our previous episode. (If you don’t remember, go back and listen to it now — it’s the third to last chapter, “The Trial of John Yates Beall as a Spy and Guerrillero.”)

After the Buffalo operation Martin and Headley busied themselves with ad hoc sabotage attempts. In late December they had a terrible fright; their dinner companion one evening was a major in the Union army, who wouldn’t shut up about rebel saboteurs. They finished their meals quickly and made themselves scarce. Then they realized why there was a military man checked into the hotel: Andrew Johnson was going to be staying at there on his way to Washington, DC. They recruited three nearby Confederate officers and came up with a plan to kidnap the Vice-President Elect.

It was beautiful in its simplicity. Headley, who had met Johnson years earlier when he was the military governor of Tennessee, would draw him into a conversation while Martin would sneak in with guns, grab the veep, and hustle him out of the hotel into a waiting transport. They rented a carriage and a team of horses, developed a series of code phrases, scouted out escape routes, and even did a quick dry run to work out their timing.

Then they tried to spring their trap only to find out that Johnson had decided to check out early. They had missed him by less than an hour.

Martin and Headley decided to keep their heads down after that fiasco.

Their old pal Kennedy was restless, though, and tried to sneak back into the Confederacy. Unbeknownst to him he had been followed by New York detectives from the moment he left Toronto. They jumped him during a rest stop in Detroit and wrestled him to the ground before he could draw his pistol.

Kennedy was dragged back to New York and stood trial before a military commission at Fort Lafayette. During the trial he attempted to bribe his jailer, Hays, to set him free; Hays refused but agreed to deliver messages to Confederate sympathizers on the outside. The sympathizers failed to pay Hays, who then ratted out Kennedy to the authorities. He made one more attempt to escape using a knife that had been smuggled into jail, failed, and spent the rest of his prison sentence clapped in irons.

Kennedy’s trial took place days after the trial of John Yates Beall, and was very similar in many ways. His primary defense was that he was not a spy, but if had been one he had good reasons for it. The commission was not impressed by this line of argument and he was found guilty and sentenced to hang.

He went to the gallows on March 25, 1865 and was defiant to the end. When the charges against him he were read out he shouted out “It’s a damn lie!” and “There is no occasion for the United States to treat me this way!” His final words were, “I know that I am to be hung for setting fire to Barnum’s Museum, but that was only a joke.”

It didn’t seem so funny to everyone else.

He was the last Confederate to be executed during the Civil War.

Connections

“Colorado” Jewett is an extremely minor figure from American history… but this isn’t his first appearance on the podcast. You may remember him from our episode on spirit photography, “What Joy to the Troubled Heart!”, where he visited the studio of William H. Mumler so frequently that Mumler eventually cut him off.

In this episode we saw that French-Canadians loved the Confederacy. They were hardly the only British subjects with that opinion. In “Shenandoahs: The Sea King” we learned that the good people of Victoria, Australia idolized the Confederates to point where they eventually made up the majority of the CSS Shenandoah‘s crew.

The extradition issues in Bennet H. Young’s trial were supposed to have been solved by the Webster-Ashburton treaty between the United States and Great Britain. We discussed the Patriot War and other events which led to the treaty in the episode “Dangerous Excitement.”

As for P.T. Barnum, this isn’t his first appearance on the podcast either. Not only did he buy several of Mumler’s spirit photographs in “What Joy to the Trouble Heart”, in “Your Heart’s Sorrow” he also offered to help find America’s first celebrity kidnap victim, Little Charley Ross — provided, of course, that Charley would then become a featured attraction at the Greatest Show on Earth.

Sources

- Balsamo, Larry T. “‘We Cannot Have Free Government without Elections’: Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Volume 94, Number 2 (Summer 2001).

- Cunningham, O. Edward. “‘In Violation of the Laws of War’: The Execution of Robert Cobb Kennedy.” Louisiana History, Volume 18, Number 2 (Spring 1977).

- Horan, James D. Confederate Agent: A Discovery in History. Pickle Partners, 2015.

- Kinchen, Oscar Arvle. <em. Christopher Publishing House, 1959.

- Longacre, Edward G. “The Union Army Occupation of New York City, November 1864.” New York History, Volume 65, Number 2 (April 1864).

- Markle, Donald E. Spies and Spymasters of the Civil War. Hippocrene Books, 1994.

- Mayers, Adam. Dixie and the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the Union. The Dundurn Group, 2003.

- McPherson, James M. “The Hedgehog and the Foxes.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Volume 12 (1991).

- Sanders, Charles W. While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

- Schultz, Duane. The Dahlgren Affair: Terror and Conspiracy in the Civil War. W.W. Norton, 1998.

- Sherburne, Michelle Arnosky. The St. Albans Raid: Confederate Attack on Vermont. History Press, 2014.

- Spence, Clark C. and Winks, Robin W. “William ‘Colorado’ Jewett of the Niagara Falls Conference.” The Historian, Volume 23, Number 1 (November 1960).

- Tidwell, William A. April ’65: Confederate Covert Action in the American Civil War. Kent State University Press, 1995.

- Van der Linden, Frank. The Dark Intrigue: The True Story of a Civil War Conspiracy. Fulcrum Publishing, 2007.

- Van Doren Stern, Philip (editor). Secret Missions of the Civil War. Portland House, 2001.

- “John Porterfield.” Civil War Talk. https://civilwartalk.com/threads/porterfield-john.188353/ Accessed 5/9/2024.

- “Luke P. Blackburn.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luke_P._Blackburn Accessed 5/9/2024.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: