The Brouhaha

when abstract art when on trial

John Quinn was dead.

In life, he had been a prominent New York lawyer, a tireless friend and patron of the arts.

In death, he was proving to be an enormous pain in the butt.

Quinn had no children, so his will specified that his art collection should be sold to support his sister, Julia Quinn Anderson. Quinn’s collection was massive, consisting of some 2,500 works of art by some of the most prominent American and European artists of the day, including Van Gogh, Seurat, Rousseau, Redon, Cezanne, Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck, Picasso, Braque, Duchamp, Gris, Rivera, and more.

As far as the art world was concerned, this was an unprecedented fire sale that created all sorts of problems for artists, collectors, and museums. One of those affected was Romanian-born sculptor Constantin Brâncuși. Quinn’s collection included numerous works by Brâncuși, and if they all went on sale at once the market for Brâncuși’s works might collapse and never recover.

Fortunately Brâncuși’s friends had a plan. Marcel Duchamp and Henri-Pierre Roché dabbled in art dealing to help fund their artistic pursuits. With Brâncuși’s assent they quietly purchased his works from the Quinn estate and then re-sold them piecemeal, helping keep the market for Brâncuși’s work stable.

Acting as Brâncuși’s agent, Duchamp set up two gallery shows in the United States: one at the Brummer Gallery in New York in November 1926, and one at the Arts Club in Chicago in January 1927. At the same time other pieces of Brâncuși’s would be included in an exhibition of international modern art at the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

So things were looking good in October 1926 when Duchamp boarded the steamship Paris with twenty pieces of Brâncuși sculpture to be exhibited and offered for sale. Well, nineteen of them at least. One sci;[tire, Bird in Space, had already been purchased by one of Brâncuși’s friends and admirers, photographer Edward Steichen, for the low price of $600.

Unfortunately for Brâncuși and Duchamp, they were about to be blindsided by something they really should have seen coming: reactionary conservatism.

It’s not hard to imagine hostility towards abstract art, partly because it still exists. Go to any museum and you’ll hear some cranky humbug proclaiming that his kids could paint that, and it doesn’t mean anything anyway, so what’s the point? Inside the art world, though, abstraction is no longer a controversial subject.

Things were very different in the 1920s. While abstract art had been making great strides towards public acceptance, it was still very much part of the avant-garde.

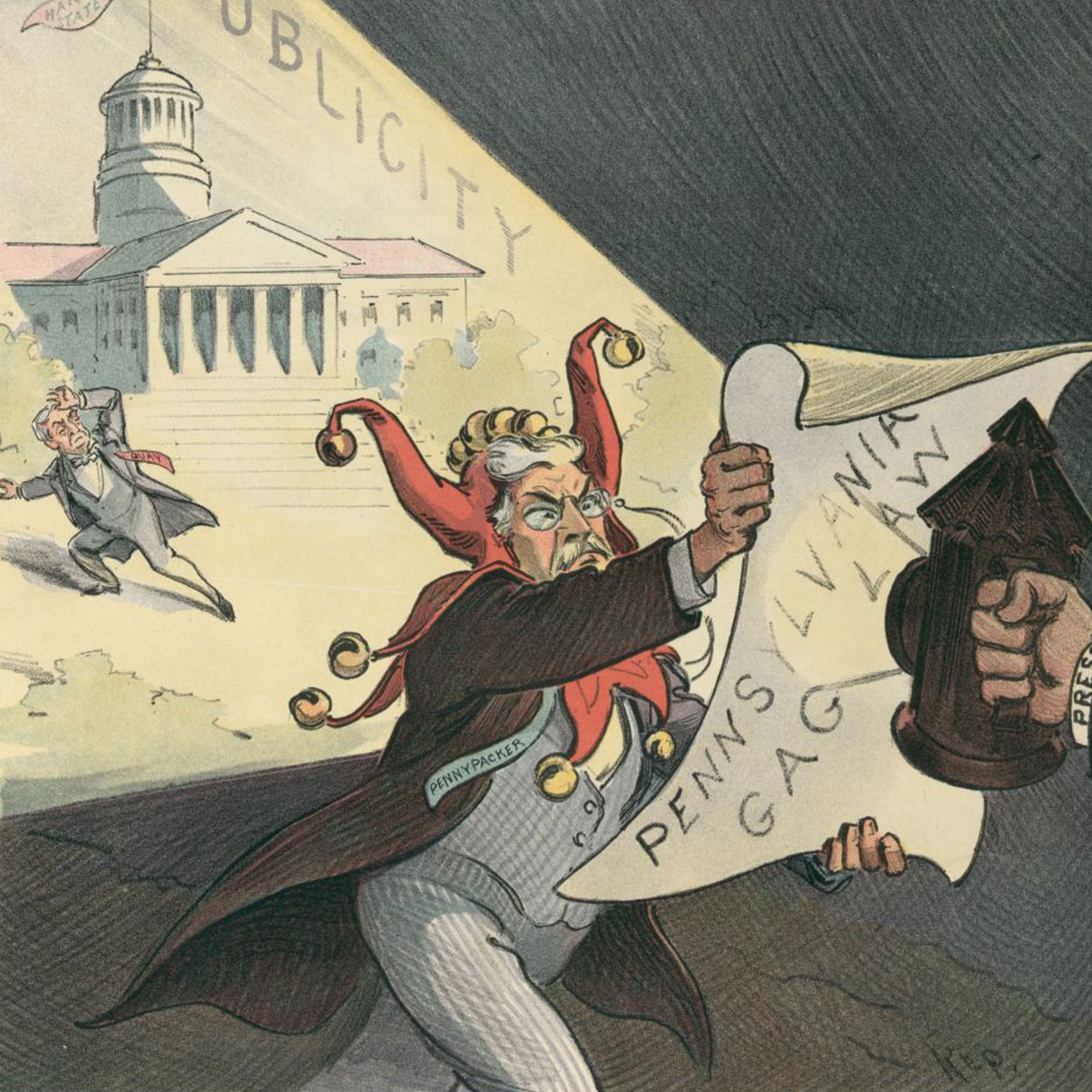

Many artists, curators and collectors had been formed by schools and systems that valued realism and technique over everything else, and they were not pleased to see what they considered the artless castoffs of talentless men passed off as high culture. There were even those who considered abstract art a moral failing, practiced by the dissipated, the feeble-minded, and the insane. (And also, the Jews, because what’s history without a solid dose of anti-Semitism.) To these critics, abstract artists were degenerates, dope fiends, perverts, the purveyors of spiritual poison.

Two of these conservative curators learned of the upcoming shows and placed a discreet call to the Customs Service, letting them know that Duchamp was trying to bring manufactured goods into the country duty-free by passing them off as art. When the Paris landed in New York, Duchamp was flabbergasted when customs inspectors pried open his shipping crates to examine the contents.

At this point I should probably describe Brâncuși’s art, for those of you who aren’t familiar.

Constantin Brâncuși had started as a student of Rodin, but under the influence of Cubism and primitivism he abandoned Rodin’s style of impressionistic sculpture and started moving towards representational abstraction.

His early works are still identifiable. His Portrait of Mademoiselle Pogany (1912) is all bold geometric forms, but still definitely a person. As the years passed he became ever more abstract. Princess X (1920) is ostensibly a bust of Marie Bonaparte, but abstracted to the point where the female form becomes a pile of polished ovoids that looks more like a penis than a person. Eventually he completely abandoned representation and moved into the realm of pure abstraction.

The work that will be the crux of our story, Bird in Space, has at various times been described as a “fat boomerang” or a “long banana.” It’s a C-shaped curve, ever so slightly fatter at the bottom and in the center, rising vertically and supported by a simple conical base. It vaguely resembles a distant whirling bird rendered in shorthand, or a diagram of the air flowing around the wing of an airplane.

The customs inspectors didn’t quite know what to make of Bird in Space. One of them joked, “If any sculptor made a thing like that and said it looked like my wife, I’d sue him or throw him off the dock.” Another cracked that one sculpture looked so much like an egg that he wanted to boil it. A specialist in manufactured metal goods by the name of Dayton was called in. He had no idea what to make of any it, either.

Meanwhile Duchamp was constantly reminding them that he needed these pieces for upcoming exhibitions, so could they please please please just let him take his stuff and be on his merry way?

Eventually they struck a compromise. Most of the pieces would be released on bond while the Customs Service made a final determination as to whether they qualified as art. Steichen’s Bird in Space would be held as a sample for customs officers to examine, since it had already been bought and paid for.

The Customs Service had its work cut out for it.

Abstract Art in the Law

The Tariff Act of 1922, which had been passed through the tireless efforts of the late John Quinn, allowed for the duty-free admission of original works of art by contemporary artists. To qualify under paragraph 1704 a sculpture had only to be the professional production of a sculptor, original, and not an article of utility. These definitions present their own problems, and in 1926 artists were already chafing at their restrictions, but they were the current criteria under which works had to be evaluated. Brâncuși’s works should have qualified easily.

The problem was that existing case law allowed the work to be evaluated by different criteria. The most relevant was United States vs. Olivotti & Company, handed down on March 28, 1916. That case involved the importation of marble garden furniture, which the importers claimed qualified for a lesser duty because they were works of sculpture. Olivotti & Company lost that case, and in the court’s decision the judges put forth a definition of sculpture as they knew it:

A work is not necessarily a sculpture because artistic and beautiful as fashioned by a sculptor from solid marble. Sculpture as an art is that branch of the free fine arts which chisels or carves out of stone or other solid materials or models in clay or other plastic substance, for subsequent reproduction by carving or casting, imitations of natural objects, chiefly the human form, and represents such objects in their true proportion of length, breadth, and thickness, or of length and breadth only[…]

Can [a work], because of its beauty and artistic character, be classified as a work of art…? We think not. In our opinion, the expression “works of art”… was not used by Congress to cover the whole range of the beautiful and artistic, but only those productions of the artist which are something more than ornamental or decorative…

The Olivotti standard had its detractors. In a December op-ed Forbes Watson, editor of The Arts, decried the idea that works of modern art had to be held to the same set of standards that governed the works of antiquity, and declared, “If standardized proportions and the extent to which the artist imitates nature are to be the test of whether a work is or is not sculpture, the works of practically every artist who is not purely academic, or at least literally realistic, would be refused free admittance by our enlightened lawmakers.”

Ultimately, the Customs Service was still baffled, so they did the only thing they could do: they called in some experts. Fortunately they knew some guys. Great guys. Curators, some of them. Very reliable, very conservative. Gave up hot tips every now and then.

You can see where this is going. The same experts who had ratted on Duchamp in gave the customs inspectors helpful opinions like, “If that’s art, hereafter I’m a bricklayer,” and “Dots and dashes are as artistic as Brâncuși’s work.”

On February 23, 1927, appraiser Frederick J.H. Kracke handed down his decision: Brâncuși’s works were not sculpture. Instead, they were classified as metal goods under the heading of “Kitchen Utensils and Hospital Equipment” and, as such, were dutiable at 40% of their value.

The cognoscenti were enraged by the decision. Some insulted the customs officials, calling them tasteless pedants and swine. Some declared that America’s art scene was backward, so far behind Europe that it would never catch up. Some mocked the very idea that the government was assessing their duties on the sale price, as if art aficionados would pay hundreds of dollars for a few pounds of bronze — in the process inadvertently equating aesthetic value with commercial value.

An editorial in Brooklyn Life and Activities of Long Island Society put it best:

The Customs Department does not appear to be as much interested in art for art’s sake as in art criticism for revenue’s sake, and instead of consulting representatives of the numerous little groups of advanced thinkers who go into raptures over the new beauties the modernists have brought to art and who would no doubt vote to tax the work of the Academicians as just so much dried paint, canvas, or metal, as the case might be, it has accepted the testimony of the back numbers and reactionaries who have all along been unanimous in the belief that the work of the ultra modernists is anything but art.

The Appeal

Brâncuși, who had already returned to Paris, would have been happy to just pay the duties and be done with what he had taken to calling “the Brouhaha.”

Steichen, on the other hand, was deeply offended that the government was promoting a definition of art promoted by reactionary critics who could not understand how the world was changing.

Duchamp was also outraged, partly because of the principle of the thing, and partly because he was now on the hook for $4,000. He was also looking at the situation as a showman and promoter. The Brouhaha had been the talk of the art world for three months. Perhaps he could galvanize artists and turn the case into a cause célèbre; change the law in his favor; raise the profile of Brâncuși, Duchamp, and Steichen; and in the process make a pretty penny.

The three of them hatched a plan. With the financial assistance of Mrs. Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, famous collector and patron of the arts (maybe you’ve heard of her museum?), they filed an appeal. Then, they launched a press blitz.

Serious men like James Earl Fraser, Rockwell Kent, and Ezra Pound wrote serious articles, attacking the ruling as backwards-looking, short-sighted, and silly. Many attacked the idea that the Olivotti standard required a slavish fidelity to realistic proportion that had never been strictly adhered to by any artist. Steichen himself quipped that, by the government’s standard, “the most perfect work of art is one of the plaster feet that chiropodists use to demonstrate corn and bunion plasters.”

Duchamp attacked the Customs Service itself, claiming he had been told that officers had decided that Brâncuși’s works in marble and wood were art — but that bronzes were not, because they were more valuable. (It probably wasn’t true, but when had that ever stopped Duchamp?) He implied that the value of the work was self-evident, quipping that, “To say that the sculpture of Brâncuși is not art is like saying that an egg is not an egg.”

Brâncuși gave a series of interviews in which he was everything he had not been during his stay in New York. He was self-effacing, humble, and careful not to say anything that might be used to portray him as a revolutionary firebrand. He always made sure to address the points the government would be raising in a court of law — mostly emphasizing that the Bird was one of a series, and not a replica. Which is strange, because no one was really contesting that.

The reactionaries had their day in the press, too. They scored easy points mocking the outward form of Brâncuși’s sculptures, and gloated that these so-called “modern artists” were finally going to get what was coming to them. There were the usual “my kid could do that” swipes. Occasionally they would throw in aspersions about Brâncuși’s sanity and morality for good measure.

Brâncuși’s Argument

Bird in Space had finally had its day in customs court on October 21st, 1927. And I mean literally: it was plunked down in front Justices Byron S. Waite and George M. Young as Exhibit 1.

Brâncuși’s side, represented by a team of the best attorneys Vanderbilt and Whitney money could buy, went first. Their arguments were simple. Brâncuși’s work met every criteria in the Tariff Act of 1922: it was the production of a professional sculptor, it was original, and not an article of utility. As for the Olivotti standard requiring art to be realistic, it had no basis in either the law or artistic practice.

To back up their arguments, they called six witnesses: Edward Steichen himself; Dr. William Henry Fox, director of the Brooklyn Museum of Art; Forbes Watson, editor of The Arts; Frank Crowninshield, editor of Vanity Fair; art critic Henry McBride of the New York Sun; and sculptor Jacob Epstein.

It was obvious to all that Bird in Space had no practical or mechanical use. The government wasn’t even trying to assert the contrary.

There was some debate as to whether the bronze Bird in Space was a reproduction of a wooden or marble original, and not one of a series. To that end, Steichen testified about the process of creating and finishing the work, which he had witnessed first-hand in Brâncuși’s studio, stressing that though the initial casting was done by professional founders, it was finished by hand and was significantly different from other works in the series. Later, Brâncuși would swear out an affidavit in Paris making essentially the same points.

They had more difficulty proving Brâncuși was a professional sculptor. After all, sculpture does not have any of the traditional hallmarks of a profession. It doesn’t require academic credentials, or a certification from a licensing board, or anything other than a desire to make art. (And thank God for that.) All Brâncuși’s attorneys could do was point to his long career, the recognition of his peers, and the opinions of the cognoscenti.

The witnesses waxed rhapsodic about the work’s aesthetic and inspirational qualities. But when pushed to define or defend their opinions, they became somewhat inarticulate. As artists and critics they had some difficulty arguing with lawyers and judges looking for objective standards and bright-line rules. Some of the testimony veered into the absurd. Steichen was cross-examined about the significance of the work’s title:

Q: What makes you call it a bird, does it look like a bird to you?

A: It does not look like a bird but I feel that it is a bird, it is characterized by the artist as a bird.

Q: Simply because he called it a bird does that make it a bird to you?

A: Yes, your honor.

[….]

Q: If you saw it in the forest you would not take a shot at it?

A: No, your honor.

Frank Crowninshield was subjected to a similar line of questioning about the work’s abstract qualities:

Q: How does it suggest a bird?

A: There is some suggestion of form, but that is not important. It is the feeling of flight.

Q: You mean it conveys the idea of a bird in flight?

A: Yes. Not a bird, but the flight of a bird.

Q: Mightn’t it also represent the flight of a flying fish, for instance?

A: No!

William Henry Fox was subjected to a line of questioning that questioned the very concept of abstraction itself:

Q: If you never heard of this sculpture or its creator, would you call it a bird?

A: I might not. Probably not.

Q: Do you think more than one person out of 10,000 using your museum would think of it as a bird?

A: I think many more than one in 10,000 would think of it as beautiful.

Probably the most persuasive (and controversial) remarks of the day were presented by Jacob Epstein, when confronted by a version of the “my kid could do that” defense. Here’s a relatively long excerpt:

Q: Do you consider from the training you have had and based on your experience you had in these different schools and galleries—do you consider that a work of art?

A: I certainly do.

Q: When you say you consider that a work of art, will you kindly tell me why?

A: Well, it pleases my sense of beauty, gives me a feeling of pleasure. Made by a sculptor, it has to me a great many elements, but consists in itself as a beautiful object. To me it is a work of art.

Q: So, if we had a brass rail, highly polished, curved in a more or less symmetrical and harmonious circle, it would be a work of art?

A: It might become a work of art.

Q: Whether it is made by a sculptor or made by a mechanic?

A: A mechanic cannot make beautiful work.

Q: Do you mean to tell us that Exhibit One, if formed up by a mechanic — that is, a first class mechanic with a file and polishing tools — could not polish that article up?

A: He can polish it up, but he cannot conceive of the object. That is the whole point. He cannot conceive those particular lines which give it its individual beauty. That is the difference between a mechanic and an artist; he (the mechanic) cannot conceive as an artist.

Q: If he can conceive, then he would cease to be a mechanic and become an artist?

A: Would become an artist; that is right.

[…]

Q: In so far as that piece of sculpture is concerned, in appealing to the aesthetic taste, it does not make any difference what it represents?

A: Not at all. There are limits.

Q: We will say a certain piece of rock, marble, is taken by a sculptor and simply chipped off at intervals. As long as that chipping off at intervals was done by a sculptor, you would consider it a work of art?

A: The moment a piece of rock, marble, is begun in the hands of the man, if he is an artist, it can become, from that moment, a work of art.

In a troubling development for the government’s defense, at one point Justice Waite questioned the Olivotti standard directly:

There is no law that I know of that states that an article should represent the human form or any particular animal form or an inanimate object, but is it as a matter of fact within the meaning of the law a work of art, of sculpture?

Eventually, court adjourned for the day. And stayed adjourned for the next five months. In the meantime, excerpts from the trial record were widely printed in newspapers around the country as humor pieces. Whether the humor came from soulless government stooges with no art in their soul, or from pie-in-the-sky artistes with their crazy avant-garde notions depended on which paper you bought.

The Government’s Argument

The trial reconvened on March 23rd, 1928. This time it was the government’s turn to present their rebuttal, and their argument was simple. They readily conceded that the Bird was original and not an article of utility, but though Brâncuși was an excellent “polisher of bronze” he was not a professional sculptor, and Olivotti required art to be representational if not realistic. They called only two witnesses to back up their points.

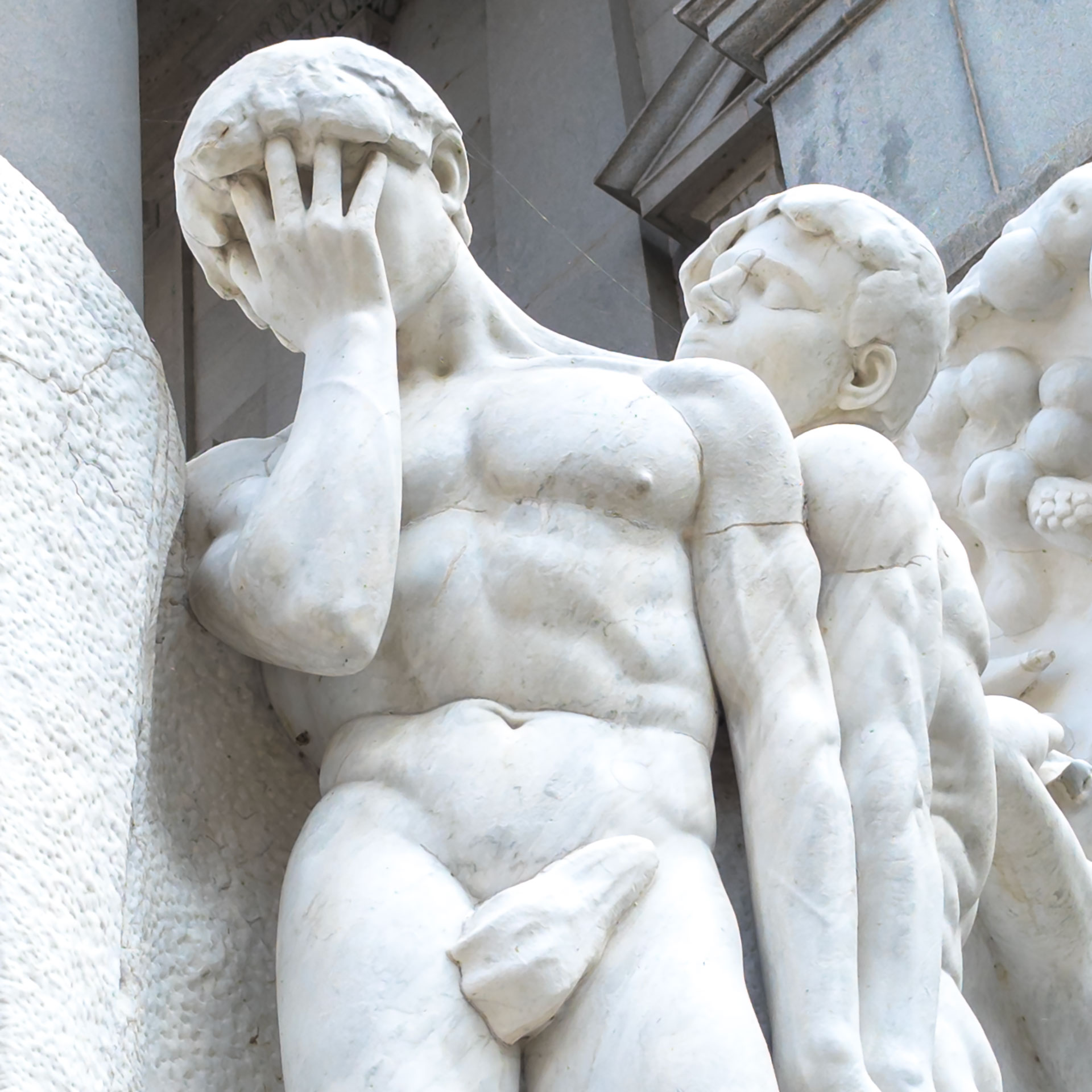

Robert Ingersoll Aitken was a celebrated sculptor of monuments in his day. He is little known today, though his works endure. They include the Dewey Monument at Union Square in San Francisco, the life-sized statue of “Iron Mike” at the Marine Corps Recruit Depot on Parris Island; and, most notably, Equal Justice Under Law, the sculpture in the West Pediment of the United States Supreme Court. His credentials as a professional sculptor were beyond reproach. He did not like the Bird. In fact, not only did he deny it was a work of art, he denied it was even a sculpture.

Q: Now, Mr. Aitken would you mind stating why this is not a work of art?

A: First of all I might say it has no beauty.

Q: In other words, it aroused no aesthetic emotional reaction in you?

A: Quite no.

Q: You would limit your answer exclusively to the fact that so far as you are concerned it does not arouse any aesthetic emotional reaction?

A: Well, it is not a work of art to me.

Q: That is the sole reason you assign for it?

A: It is not a work of art to me.

The government’s second witness was Thomas Hudson Jones, sculptor and professor at Columbia University. Again, he is little known today, though if you’ve ever visited the Tomb of the Unknown Solider you’ve appreciated his work. Like Aitken, his credentials were above reproach, and like Aitken, he did not think much of the Bird.

Q: Why do you regard Exhibit 1 as not a work of art?

A: It is too abstract and a misuse of the form of sculpture.

Q: That is your sole reason for not regarding Exhibit 1 as a work of art?

A: I don’t think it has a sense of beauty.

Q: If it did arouse in you a sense of beauty you would state it is art?

A: Yes.

Q: So you base your opinion as to whether Exhibit 1 is or is not art on the emotional reaction to the presence of beauty or the absence of beauty?

A: Yes.

Brâncuși’s lawyers chipped away at Aitken and Jones’s testimony, trying to prove that their opinions were personal and subjective, only to have their lines of questioning shut down as hearsay.

The government witnesses had the academic credentials that Brâncuși’s witnesses lacked, which gave their arguments some additional heft. However, while Brâncuși’s became inarticulate when cross-examined, the government witnesses turned into surly children who think automatically gainsaying everything you say is a winning strategy.

And that was it. Both sides filed some additional briefs, but arguments were over. Now, it was in the hands of the Judges. Young, a newcomer to the court, was relatively untested. Waite was 75 years old and not exactly known for being liberal, but had asked some penetrating and thoughtful questions during the trial. They took some time to ponder the matter.

Eight months, to be exact. On November 28th, Justice Waite handed down his decision.

The Verdict

Was Bird in Space original work, and not a reproduction? Even the government wasn’t contesting this point.

Was Brâncuși a professional sculptor? Here Waite dismissed the sour grapes testimony of the government experts and went with the more nuanced testimony of Brâncuși’s team artists, writers, and aesthetes.

The only remaining question was whether Bird in Space was a sculpture. Here Waite noted that paragraph 1704 did not define what a sculpture was, other than to offer a stilted dictionary definition, and specify that it could not be an article of utility.

The government’s argument, of course, hinged on Olivotti‘s definition of what a sculpture was, which required it to be representational and stated that it had to be more than merely ornamental or decorative. To that, Judge Waite noted:

This decision was handed down in 1916. In the meanwhile there has been developing a so-called new school of art, whose exponents attempt to portray abstract ideas rather than to imitate natural objects. Whether or not we are sympathy with these newer ideas and the schools which represent them, we think of the fact of their existence and their influence upon the art world as recognized by the courts must be considered.

The object now under consideration is shown to be for purely ornamental purposes, its use being the same as that of any piece of sculpture of the old masters. It is beautiful and symmetrical in outline, and while some difficulty might be encountered in associating it with a bird, it is nevertheless pleasing to look at and highly ornamental, and as we hold under the evidence that it is the original production of a professional sculptor and is in fact a piece of sculpture and a work of art according, to the authorities above referred to, we sustain the protest and find that it is entitled to free entry under paragraph 1704, supra. Let judgment be entered accordingly.

And that was it. The Brouhaha was finally over. Brâncuși and Duchamp had won a great victory for art importers, Steichen got his bronze and his $240 back, and the world was safe for abstraction forever!

…

Still reading?

Of course you are. Because the story doesn’t end there.

If you look back at Justice Waite’s opinion, he doesn’t actively strike down the part of the Olivotti standard requiring sculpture to be realistic. He just says other schools of art “must be considered.” And the other part, requiring sculptures to be more than “merely decorative?” He doesn’t even touch that at all.

As a precedent the Brâncuși ruling is worthless. When it was convenient the Customs Service’s attitude towards other schools of art became, “We considered them, and rejected them.” Less than a decade later in 1936 Customs tried to level duties on Cubist sculptures bound for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art. They were slapped down, but continued to arbitrarily enforce the Olivotti standard when they thought the political climate was more favorable to their arguments.

And let’s not forget that the Brâncuși ruling can be easily construed to only apply to sculpture!

To this day, there is no single consistent definition of what art is in the law. While it seems unlikely that the government would take aim at art they consider illegitimate, there’s also nothing to stop them from trying if they felt like it. And the government is doing more and more unlikely things every day.

Amazingly, perhaps the best legal defense of abstract art in any form was articulated by Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, whose concurring opinion in 1987’s Pope vs. Illinois said:

I must note, however, that in my view it is quite impossible to come to an objective assessment of (at least) literary or artistic value, there being many accomplished people who have found literature in Dada, and art in the replication of a soup can. Since ratiocination has little to do with esthetics, the fabled “reasonable man” is of little help in the inquiry, and would have to be replaced with, perhaps, the “man of tolerably good taste” — a description that betrays the lack of an ascertainable standard. If evenhanded and accurate decision making is not always impossible under such a regime, it is at least impossible in the cases that matter. I think we would be better advised to adopt as a legal maxim what has long been the wisdom of mankind: De gustibus non est disputandum. Just as there is no use arguing about taste, there is no use litigating about it.

At least it all ended happily for Steichen. His Bird in Space eventually wound up in the Seattle Art Museum. You can see others in the series in museums around the world, including the Met, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the National Gallery of Art.

Photo by Rob Corder. (Cropped ever-so-slightly from the original.)

Connections

John Quinn avidly collected many artists, including Sir Jacob Epstein. Epstein’s monumental Social Consciousness was originally intended for Philadelphia’s Ellen Phillips Samuel Memorial (“The Icelander”).

Quinn is buried in Fostoria, OH. Other notable burials in Fostoria include Hettie Purnell, the daughter of would-be Messiah “King Ben” Purnell of the House of David (“Exceeding Great”).

Ezra Pound would later go on to be an admirer of “American Hitler” William Dudley Pelley (“Seven Minutes in Heaven”).

Government witness Robert Ingersoll Aitken was the sculptor of the Dewey Monument in San Francisco, celebrating Dewey’s victory at the Battle of Manila Bay (“He Fired When Ready”).

Sources

- Cabanne, Pierre. Constantin Brancusi. Paris: Terrail, 2002.

- Giry, Stéphanie. “An Odd Bird.” Legal Affairs, Sept/Oct 2002.

- Hartshorne, Thomas L. “Modernism on Trial: C. Brancusi v. United States (1928).” Journal of American Studies, Apr. 1986.

- Kammen, Michael. Visual Shock: A History of Art Controversies in American Culture. New York: Knopf, 2006.

- Lanza, Emily. “Bird in Space: Is it a bird or is it art?” The Legal Palette, 21 Mar 2018. https://www.thelegalpalette.com/home/2018/3/20/brancusis-bird-in-space-is-it-a-bird-or-is-it-art Retrieved 8/10/19.

- Mann, Tamara. “The Brouhaha: When the Bird Became Art and Art Became Anything.” Spencer’s Art Law Journal. 12 Dec 2011. http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/news/spencer/spencers-art-law-journal-12-9-11.asp Retrieved 8/10/19.

- Pham, Michelle. “Art: A Brief Retrospective on the Legal Term.” The Sci Tech Lawyer, Vol. 14 No. 2, Winter 2018.

- Brancusi v. United States. 54 Treas. Dec., 428.

- United States v. Olivotti & Co. 30 Treas. Dec., 586.

- Watson, Forbes. “What is a Sculpture Made Pertinent Query by Action of Our Custom’s Officials.” Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, 26 Dec 1926

- “Modern Art Poisoning our Minds and Morals.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 26 Dec 1926.

- “Brancusi Must Pay Duty on Sculpture.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 24 Feb 1927.

- “Artist or Bootlegger?” Brooklyn Life and Activities of Long Island Society, 26 Feb 1927.

- “Brancusi, Modernist Sculptor, Bows Meekly to Kracke’s Stand Barring His Work From U.S.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 Mar 1927.

- “Whatever This May Be – ‘It is Not Art.’ San Francisco Examiner, 20 Mar 1927.

- “Fish or Art? Court Perplexed at Bird That May Be Beast.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 22 Oct 1927.

- “Modernist Art Balks the Government’s Custom Sleuths.” Muncie Evening Press, 31 Oct 1927.

- “How They Know It’s ‘A Bird’ and Are Sure It is ‘Art.'” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, 25 Dec 1927.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: