The Icelander

a tale of public art, politics, and racism

Ellen Phillips Samuel was the daughter of one of Philadelphia’s wealthiest and most prominent Jewish families.

They were proud members of the Congregation Mikveh Israel, the oldest synagogue in the United States, and claimed descent from Haym Salomon, an early patriot who supported the American Revolution both by spying and by purchasing government debt, and who died penniless as a result. More recently, her uncle was Henry Myer Phillips, the first Jewish congressman from Pennsylvania, and one of Philadelphia’s most noteworthy nabobs.

In 1913, as Mrs. Samuel felt her end approaching, she yearned to leave her mark on the city she loved, just as her ancestors had. In her will she left an endowment of half a million dollars for the Fairmount Park Art Association, to be paid out after the death of her husband Joseph Bunford Samuel, along with some specific notes about how it was to be used.

There is a space of two thousand feet commencing from the Beacon Light or last boathouse to the Girard Avenue Bridge. On the edge of this ground bordered by the Schuylkill River is a stone bulkhead. On top of this embankment it is my will to have erected at distances of one hundred feet apart, on high granite pedestals of uniform shape and size, statuary emblematic of the history of America, ranging in time from the earliest settler of America to the present era, arranged in chronological order, the earliest period at the South end, and going on to the present time at the north end; and when all the statues are in place, the income to be spent in buying Statuary and Fountains to decorate the park according to the judgment of the Commissioners.

The Fairmount Park Art Association was grateful to receive such a generous bequest. Well, grateful for the money, at least. They hated every other aspect of the bequest. They thought a series of statues lining Kelly Drive would be a hideous eyesore. Instead, they hired architects to design three terraced sculpture gardens, and eventually revealed their plans and a scale model to the public.

The Association hadn’t reckoned with Ellen Phillips Samuel’s husband, J. Bunford Samuel. He was very insistent that his wife’s bequest was for statues and statues alone, and never hesitated to remind commissioners and the public of that fact. In the face of his objections, the commissioners decided to sit on their plans and take no public action. What would be the harm? They weren’t going to get the money until after his death, anyway, and this way they wouldn’t have to listen to his kvetching.

J. Bunford Samuel could see what they commissioners were doing. Rather than see his wife’s wishes ignored, he decided he would have the first statue erected at his own expense. If he presented it to the Art Association as a fait accompli, they’d have to put it into place, and it would shame them into following the plans laid out in the bequest.

Ellen’s bequest specified that the statues should range in time “from the earliest settler of America to the present era,” so Bunford decided to start at the beginning, with the first settler of America. But who could that be?

The Icelander

Now, if we’re being honest with ourselves, the earliest settlers were Native Americans, but this was the early 1900s and there’s no way anyone involved in this story was going to admit that.

You could always make a case for Jamestown, Virginia or St. Augustine, Florida for being the first permanent European settlements in North America. However, at the time there was a growing consensus that the earliest European settlers of North America were Vikings. The Vikings had written about their explorations of “Vinland” in two Icelandic sagas, the Graenlandiga Saga and the Saga of Eirik the Red, but they had long been dismissed as fanciful exaggerations or outright fabrications.

In the late Nineteenth Century, scholars started to examine the sagas with a critical eye and realized they might be more accurate than previously thought. This was partly driven by increased access to the sagas themselves, and partly by the spirit of open-minded scientific inquiry. If it also happened to prove that a proper, white Northern European had discovered North America before some garlicky Italian or chorizo-chugging Spaniard, even better.

Enter Thorfinn Karlsefni, son of Thord-Horsehead, son of Snorri, son of Thord, son of Bjorn Butter-box, son of Thorvald-Hrygg, son of Asleick, son of Bjorn-Ironside, son of Ragnar-Shaggy-Breeches.

Thorfinn was a wealthy man of noble lineage: he claimed descent from legendary king Swedish king Ragnar Loðbrók and Irish king Cerball mac Dúnlainge. All the historical sources agree: he was totally awesome. So awesome that his nickname, “Karlsefni,” is basically an idiomatic way of saying “whatta man.”

Sometime around 1000 AD Thorfinn arrived in Greenland from Norway. The sagas are silent as to why he traveled to Greenland but let’s be honest: no one went to Greenland if they had options back in Europe. While wintering with Leif Eiriksson he married Gudrid, the widow of Leif’s brother Thorstein, and the happy couple decided to make their home in Vinland.

In spring, Thorfinn and Gudrid set off for Vinland with a mixed party of men and women. They landed at Straumfjord, where Leif had built some temporary housing on one of his previous voyages, and spent their first year clearing the land around those houses for agriculture and living off the land. Gudrid even gave birth to Thorfinn’s son, Snorri, the first European born in North America. (Take that, Virginia Dare.)

Later the settlers had their first encounters with the mysterious “Skraelings” — likely tribes of the pre-Inuit Dorset or Thule peoples. Their first encounters were peaceful, but put the Vikings on edge. Later encounters turned violent, and the Vikings only survived because the Skraelings were superstitious and fearful. Realizing that they were hopefully outnumbered, Thorfinn and his party gathered all the produce they could and sailed back to Greenland. After a few profitable trading expeditions between Greenland and Norway, Thorfinn retired to Icleand and passed into legend.

That’s the version of the story presented in the Graenlandiga Saga, at least. The Saga of Eirik the Red agrees on the outline but differs on the details — whether Karlsefni traveled with Leif’s brother Thorvald and sister Freydis, how long they stayed in Vinland, exactly how long their encounters with the Skraelings played out.

Of course, the Saga of Eirik the Red also claims that Thorfinn and company also encountered a legendary one-footed creature who shot Thorvald Eiriksson in the junk with an arrow.

Yes it is true

That our men chased

A uniped

Down to the sea

The weird creature

Ran like the wind

Over rough ground

Hear that, Karlsefni

So, um, maybe take everything The Saga of Eirik the Red says with a grain of salt. A whole cellar, even.

If you’re looking for someone to be the first European settler in North America, Thorfinn Karlsfeni is a fine choice. There was only one problem: a complete lack of archaeological evidence of Viking colonization. Today, of course, we know all about the Viking settlement at L’Anse aux Medows on Newfoundland, but that wasn’t discovered until 1960. Other evidence would have to suffice.

Almost every region along the east coast had some old rock covered with crude markings, either natural or manmade. As the search for evidence of Viking settlements expanded, these old rocks were suddenly discovered to be “runestones” containing messages left by Viking explorers, proving that they’d been everywhere from St. John’s to Long Island. (And sometimes even as far inland as Minnesota and Oklahoma.)

Many of them were obvious frauds. Others have markings so vague that over the years they’ve been interpreted to be Norse, Celtic, French, Hungarian, even Phoenecian or Japanese. But the archaeologists of the late Nineteenth Century frequently took them to be legitimate.

One of these “runestones” was discovered near Yarmouth, Novia Scotia in 1819. It remained a curiosity until 1884, when an amateur archaeologist declared it was “neither a modern fraud nor the work of the wayward playfulness of the leisure hours of the sportive red-skin.” He claimed the description was runic, and translated it as “Hako’s son addressed the men.” He associated the “Hako” of the inscription with a slave named “Haki” from the Saga of Eirik the Red, and pronounced it conclusive proof that the Vikings had landed in Nova Scotia.

As J. Bunford Samuel researched the early settlers of America, he stumbled across that amateur scholar’s paper. He also stumbled across any number of careful, reasoned refutations of these arguments. Those refutations didn’t have as much weight as the name attached to that first paper, though.

It was Henry M. Phillips Jr. His late brother-in-law.

Conclusive evidence of the first settler in America, provided by his late wife’s own brother? It was too perfect to be true. J. Bunford Samuel had the subject for his statue.

The Other Icelander

Of course, he still needed to get that statue made. Local artists seemed suspiciously uninterested in the lucrative commission, perhaps fearing the wrath of the grandees of the Fairmount Park Art Association. Then Bunford’s friend Henry Goddard Leach, president of the American-Scandinavian Foundation, made a brilliant suggestion: get an Icelander to sculpt an Icelander.

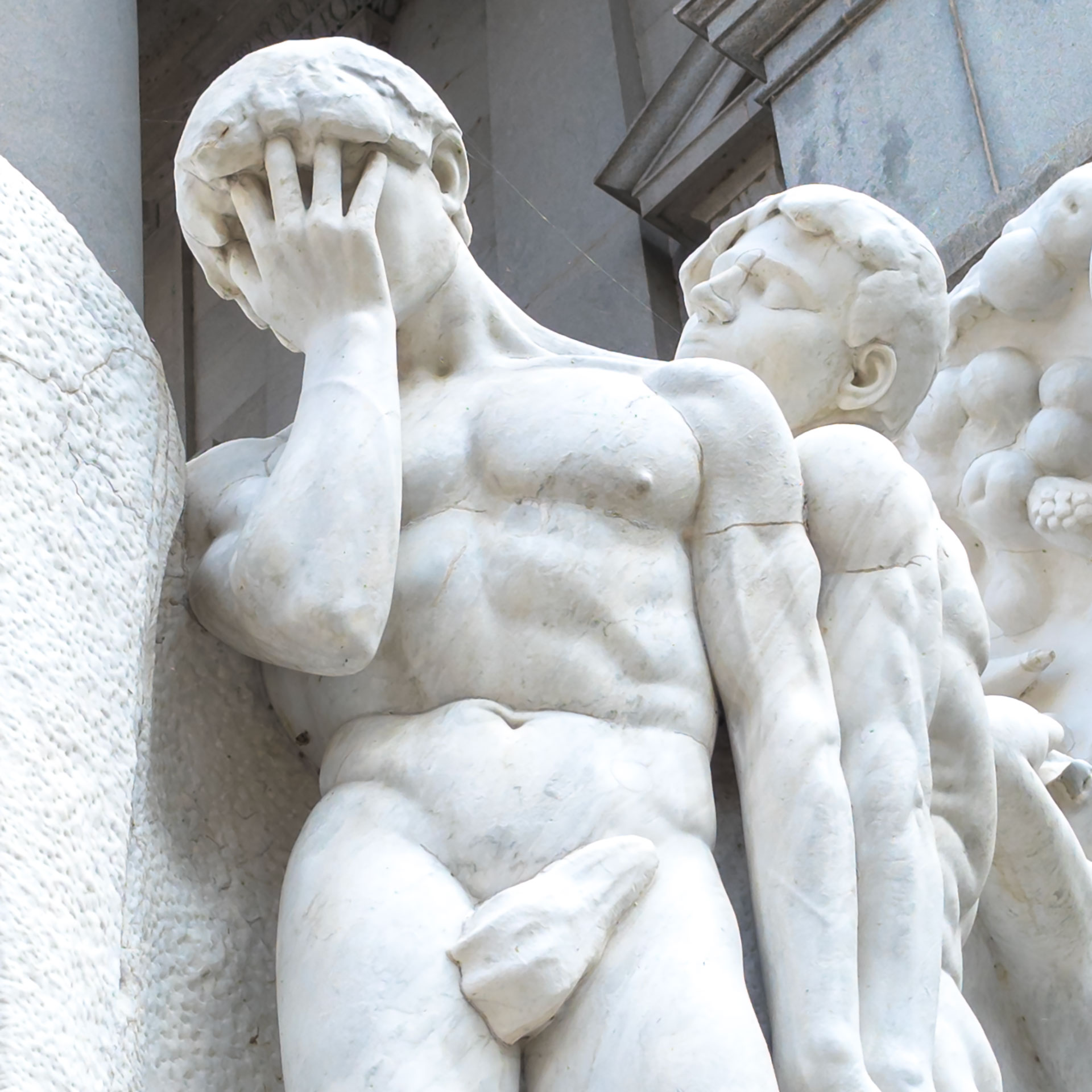

Leach introduced Samuel to Einar Jónsson, the greatest Icelandic artist of the day. He was perfect for the project, as he had a powerful expressionistic style and a deep interest in Icelanding history and folklore. The composition he came up with was simple but powerful: a fresh-faced young Thorfinn, leaning on his axe and peering adventurously into the future, while he carries the legacy of the past on his back via an inscription on his shield.

Einar made several trips to the United States to work on the statue, supervise the casting, and design a pedestal. By 1919 Thorfinn Karlsefni was complete, and a beaming J. Bunford Samuel presented it to the Fairmount Park Art Association.

Who stuck it in a utility shed and just let it sit there. For almost two years. When Bunford asked them to explain themselves the only response he got was that it was being “worked on.”

Eventually, Samuel was able to badger the Art Association into installing the statue and the unveiling was scheduled for 2:30 PM on November 20, 1920. A number of impressive guests were invited, including George Bech, Consul-General of Denmark and Iceland; representatives of the American-Scandinavian Foundation; Dr. Halder Hermannson of Cornell University, the nation’s leading authority on Icelandic history and language; and the editors of America’s largest Norwegian and Danish-language newspapers.

When the time came for the unveiling, the commissioners and visiting dignitaries were nowhere to be found. One of the park guards decided that it looked like rain and he’d rather not wait around to find out. He seized the initiative and whipped the tarp off.

Of course, that was when the commissioners finally arrived. They had been posing for photographs for a group portrait down at City Hall and got stuck in a traffic jam. Whoops. They made some perfunctory speeches, explaining just why there was a statue of a Viking in Philadelphia and calling it a major milestone in American/Icelandic relations. And then they retired somewhere for brandy and cigars. And maybe, just this once, pickled herring.

Over the years, the handsome statue became a favorite of the people of Philadelphia. Also the people of Iceland and Denmark. J. Bunford Samuel was even elevated to the Order of the Falcon, Iceland’s only chivalric order, by King Christian X in 1929.

But to the Fairmount Park Art Association, Thorfinn Karlsefni was still an eyesore that didn’t fit in with their plans. When J. Bunford Samuel finally died in 1929 they went full steam ahead with their terraced sculpture gardens, which were completed in three stages between 1933 and 1961.

Critics and the public were not so entranced with the sculptures erected by the Art Association. The terraces were nice, and the landscaping and gardens were top-notch. But the sculptures? Eh. One critic claimed the first completed statue, Robert Laurent’s The Spanning of the Continent, looked like it was “hit on the head and banged up from the bottom.” And let’s be honest, many of the statues are nice but forgettable, with the possible exception of Jacques Lipchitz’s powerful The Spirit of Enterprise.

Stupid Stupid Skinheads

Meanwhile, Thorfinn Karlsefni stood his lonely vigil on the banks of the Schuykill River. As the years went by, he became a focal point for Phladelphia’s Leif Erikson Day celebrations.

If you don’t celebrate Leif Erikson Day where you live, just think of it as another ethnic holiday, a light-hearted celebration of pan-Scandinavian heritage. It’s usually celebrated on October 9, and while the date itself is not particularly significant, you have to imagine some celebrants are probably tickled that it usually falls a few days before Columbus Day on the calendar.

Most years there might just be a picnic or a speech by the statue. If you were lucky, you might have seen a re-creation of Leif Eirikson landing on the shores of Vinland, complete with a replica Viking longboat crewed by proud, slightly-inebriated Scandinavian-Americans. It was all was about as historically accurate as an episode of Hercules: The Legendary Journeys but it who cares? A good time was had by all.

Sometime in the mid-2000s those celebrations turned dark when they were taken over by white supremacists. Like Hitler they saw the Vikings as an unconquered bastion of pure Germanic whiteness. Since the statue was the only Viking site in Philadelphia of any significance, the skinheads chose it as a rallying point. Poor Thorfinn was probably confused, because skinhead ideas of whiteness and racial purity would have been completely alien to him.

The organizer of these white power rallies was Keystone United. (They used to be the “Keystone State Skinheads” but they changed it because it’s hard to pretend you’re the good guys when “skinhead” is right there in your name.) Like many white supremacist organizations, Keystone United tries to present themselves as a non-controversial organization safeguarding the rights of white Americans against the rising tide of diversity, but its members have a long history of violent, racially-motivated assaults. They’re classified by the Southern Poverty Law Center as a hate group.

The first few Keystone State Skinhead rallies at the statue were low-key impromptu gatherings. Their 2008 event drew some 75 skinheads to Fairmount Park, but was also notable for being a comedy of errors. Since they were operating without a permit, they’d failed to notice that their rally was scheduled for the same time as a regatta. They were squeezed out of the area around the statue and had to cut their festivities short. They laid a wreath at the feet of the statue — but statched it back a few minutes later since, once again, they were operating without a permit and didn’t want to get fined for littering. At least one passer-by was confused by the “KSS” logos on their shirts and thought he was watching a gathering of the KISS Army.

During the Obama years, Keystone United’s numbers started to dwindle. As their celebrations got smaller, though, they got louder. They also attracted anti-racist counter-protests, which quickly grew to dwarf the offending rallies. The site of skinheads being stared down by a coalition of African-Americans, anarchists, drag queens, and Antifa was something to behold.

The real victim in all of this was the poor Thorfinn Karlsefni statue. Before, many it had settled into a sort of benign obscurity. Now, Philadelphians thought of if as “the place where all the skinheads hang out.”

In advance of the October 2017 rally, vandals defaced the statue with red spraypaint, anarchist symbols, and “anti-Nazi language.” (You can make an educated guess what that language might were, but they’re blurred in most news reports so I can’t say for sure.) But he was soon cleaned up and good as new.

He didn’t fare so well on October 2, 2018. Philadelphia police officers responding to a vandalism in progress call discovered that the statue had been knocked off of its pedestal and dragged into the Schuylkill.

Most people assumed the statue was toppled to spoil Keystone United’s fun, but it was also noted out that the Philadelphia Eagles were facing off against the Minnesota Vikings the following weekend. So, either the work of Antifa, or rabid football fans. Either explanation seems equally plausible.

(Never change, Philadelphia.)

The city used divers and a crane to extract the Viking explorer from the muck at the bottom of the Schuylkill and get him into the conservator’s studio. The damage was extensive, so this wouldn’t be a quick polish like the previous year’s clean-up. It would require time and money. The city also had to grapple with the fact that the local monument had been appropriated by white nationalists and figure out what they could do to prevent further abuse from either side of the debate.

And then, of course, 2020 happened, and no statue was safe. You’d think Thorfinn would be relatively insulated from the debate, if only because he was relatively obscure and didn’t leave much of an ongoing stain on our national fabric. Then again, if you were one of his Irish or Scottish slaves you might think differently… and he did kill quite a few Skraelings when he was here.

Thanks to these thorny issues, Thorfinn is still gone from Fairmount Park today, nearly two years later. Will he ever return to his pedestal? I dunno. Go ask Kirk Savage, he’s probably got a better idea.

I do hope some solution can be found, whether the statue is given a few extra coats of graffiti-resistant paint or relocated indoors to the art museum. Einar Jónsson’s artistry deserves an appreciative audience.

If you are dying to see Thorfinn in all his glory, there is another casting of the statue. Unfortunately, it’s in Reykjavik. So good luck with that.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

The Yarmouth runestone, whose translation by Henry Phillips Jr. inspired his brother-in-law to choose Thorfinn Karlsefni as a suitable subject, was one of many dubious “Viking runestones” found throughout North America in the Nineteenth Century (“Westward, Huss”).

One of the pieces commissioned for the Ellen Phillips Samuel Memorial was Sir Jacob Epstein’s “Social Consciousness.” Unfortunately, it the finished piece couldn’t fit into the plan and was relocated to the University of Pennsylvania. Early in his career, one of Epstein’s most important patrons was John Quinn. Quinn was also a patron of Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi (“The Brouhaha”).

Thorfinn Karlsefni is briefly mentioned in our holy text, Strange Stories, Amazing Facts in the article “The Westward Urge” (p. 216).

Scandinavians wouldn’t seriously make another serious attempt to colonize the New World until the foundation of New Sweden in the mid-1600s (“Nya Sverige”).

Sources

- Brown, R. Balfour. Description of Runic Stones Found Near Yarmouth, Nova Scotia. Self-published, 1896.

- Magnusson, Magnus and Pálsson, Hermann. The Vinland Sagas. New York: Penguin Books, 1965.

- Samuel, J. Bunford. The Icelander Thorfinn Karlsefni Who Visited the Western Hemisphere in 1007. Self-published, 1922.

- “Ellen Phillips Samuel Memorial (1933-1961).” Association for Public Art. https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/ellen-phillips-samuel-memorial/ Accessed 8/5/2020.

- “Thorfinn Karlsefni (1918).” Association for Public Art. https://www.associationforpublicart.org/artwork/thorfinn-karlsefni/ Accessed 8/5/2020.

- “Park art work will begin soon.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 23 Jan 1914.

- “Model of park statues shown.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 Jan 1916.

- “Show norse statue.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 14 Jul 1918.

- “Park guards do unveiling honors.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 21 Nov 1920.

- “Danish King bestows order on Philadelphian.” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, 6 Mar 1928.

- “Joseph B. Samuel, art devotee, dies.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 Jan 1929.

- “Samuel fund for river bank plan set free.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 Jan 1929.

- Hugh, Scott. “Art on East River Drive.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 Jun 1953.

- “Terrace statues in park finished after 48 years.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 12 Jun 1961.

- “48 years later, statues are ours.” Philadelphia Daily News, 16 Jun 1961.

- “The Scene.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 27 Sep 1976.

- “The Scene.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 1 Oct 1995.

- DiFilippo, Dana and Farr, Stephanie. “A new way of hate.” Philadelphia Daily News, 29 Oct 2008.

- Farr, Stephanie. “Unblurred face of ‘new’ skinheads.” Philadelphia Daily News, 29 Oct 2008.

- Bender, William. “Protest planned for skinhead rally.” Philadelphia Daily News, 18 Oct 2013.

- Steele, Allison. “Protesters greet skinheads.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 20 Oct 2013.

- Madej, Patricia. “Statue of ‘Icelandic hero’ near Boathouse Row found in Schuylkill River.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 2 Oct 2018.

- Sasko, Claire. “Some people really hate this Boathouse Row viking statue.” Philadelphia Magazine, 2 Oct 2018. https://www.phillymag.com/news/2018/10/02/viking-statue-boathouse-row/ Accessed 8/5/2020.

- Madej, Patricia “Viking statue submerged in Schuylkill.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 Oct 2018.

- “Fate of Viking statue uncertain after being recovered from Schuylkill River.” Action News 6, 3 Oct 2018. https://6abc.com/boathouse-row-vandal-sends-viking-statue-into-schuylkill-river/4389901/ Accessed 8/5/2020.

- Lakey, George. “Viking values are nothing like those of white supremacists.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 Oct 2018.

- Thompson, Gary. “Where is the viking statue that got toppled?” Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 Jan 2020.

Links

- Claire Sasko

- Dana DiFilippo

- Patricia Madej

- Stephanie Farr

- Leif Ericson Viking Ship, Inc.

- Southern Poverty Law Center: Keystone United

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: