Such Was Railroading

the Castle Shannon Railway War

Post-Civil War America was a capitalist’s dream.

Possibility was everywhere. There were billions of acres of virgin land ready to be stripped for raw materials just as soon as you got rid of all the inconvenient Native Americans; an unstoppable industrial juggernaut ready to rebuild and exploit the defeated foe it had just finished burning down to the foundations; and brainiacs constantly coming up with new inventions that could change everything for all time. If you were clever, or determined, or even just lucky, there was money to be made.

It certainly didn’t hurt if you were utterly amoral. The market’s prevailing attitude was that if it wasn’t actively illegal it was A-OK. That gave a lot of businessmen incentive to find ways to make money that were completely unethical but hadn’t been outlawed yet.

Here’s one of those stories.

The Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Rail Road

In 1844 Milton D. Hays was born in Birmingham, Pennsylvania, a small city on the Monongahela that’s now Pittsburgh’s South Side.

Like many young men, Hays dreamed of striking it rich. In 1863 he set out for California to make his money in gold, only to discover that all the money had already been made. Crestfallen, he returned home the following year and became the financial manager of the lumber company of Messrs. J. & A. Hays, with Mr. J. Hays being Milton’s father.

Lest you think he was just a nepo baby, Hays was also elected the vice president of Birmingham’s Merchants and Mechanics Bank in 1866. (Though I’m pretty sure daddy had a hand in that, too.)

He still dreamed of being a millionaire, though.

In the early 1870s there was one sure-fire way to make an absurd amount of money: the railroad.

So on September 24, 1871 Milton D. Hays founded the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railway. The chartered purpose of the company was to transport coal and passengers from the booming mining towns of southwestern Pennsylvania to Pittsburgh. Many of Hays’ business associates were eager to buy in, and Hays himself was chosen to fill the job of both president and superintendent. (What we’d call a managing director, these days.)

The fastest way to grow a new company is to acquire the assets of another company, and that’s exactly what Hays did. His first act as president was to purchase the Coal Hill Railroad from the Pittsburgh Coal Company for $225,000 and the assumption of $50,000 in debt. (That’s a $7.2 million deal in modern money.)

It was an interesting choice for an acquisition, mostly because the Coal Hill Railroad did not go near the South Hills markets Hays was trying to reach. Instead, it ran about a mile and a half along the south face of Mount Washington before plunging into a narrow tunnel and ending about halfway up the north face of Mount Washington, where a funicular or inclined railway took the cars down to river level. If you weren’t planning to go from the Oak Hill Mine to a coal yard on Carson Street, well, you were out of luck.

And keep in mind that trip was for coal only! The tunnel through the mountain was too short and poorly ventilated for passenger service, so passengers had to disembark on the southern end of the tunnel and take one incline to the top of the mountain, and another back down the other side.

The Coal Hill also ran on an unusual 40″ gauge, which was standard for mine carts but narrow for trains. That would not be a problem, though, because the purchase gave the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon all of Coal Hill’s equipment, including three locomotives, rolling stock, horses, stables, coke ovens, and the aforementioned incline and coal yard.

Still, it was a start. The next step of Hays’ plan involved extending the rails to the rich coal mines of Mollenauer and Castle Shannon. That would require building a steep switchback from the Mount Washington tunnel to the banks of the Saw Mill Run, and then running another six-and-a-half miles of track along the banks of the creek then stopping at a yard near Arlington.

It was an ambitious construction project, but Hays was optimistic that he could have it completed by May 1872 and threw thousands of dollars into acquiring the land, regrading it, and laying track.

Of course, one of the big ways to make money as a railroad was by building company towns along your right-of-way. In April 1872 Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon started selling lots for the community of Fairhaven. Many of the company’s officers and employees purchased homes there.

Hays was off by six months, but the new line finally opened for business in November 1872.

The Pittsburgh, Castle Shannon & Washington Railroad

The Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon was immediately popular with passengers, partly because it made reaching Pittsburgh a snap, and partly because the company had built numerous attractions along the line to encourage ridership, like a revival camp, a zoological garden, and a picnic area. It was popular with industrial concerns, too. Within four years the company’s rolling stock had expanded to include six locomotives, seven passenger cars, and 416 coal cars.

For Milton D. Hays, that was not enough. The company’s charter called for the line to extend another 7.5 miles to Finleyville, and he was eager to get that track laid. The other directors and stockholders repeatedly shot him down, because they saw extending the line as an enormous capital expenditure that would take years to produce marginal rewards. They were quite happy to exploit the line they already had.

In 1876 Hays took the matter out of their hands by forming a second company, the Pittsburgh, Castle Shannon & Washington Railroad. Its charter called for it to run trains from Castle Shannon to Finleyville, and eventually to Washington, PA; Morgantown, WV; and points beyond.

Now, laying another 7.5 miles of track was a daunting task, but Hays was nothing if not resourceful. He used his keen business mind to negotiate a joint operating agreement with the president and superintendent of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon, allowing the Pittsburgh, Castle Shannon, & Washington free use of the other company’s right of way, rolling stock, men, and material.

It helped that all three men were, of course, Milton D. Hays. As N.A. Critchett put it in his highly entertaining article “Double Gauge”:

President Milton D. Hays of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad made out the lease to President Milton D. Hays of the [Pittsburgh, Castle Shannon, & Washington Railroad] and both presidents were eminently satisfied.

N.A. Critchett, ”Double Gauge”

The companies became so intermingled that most outside observers were not even aware there were two separate companies. Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon employees and equipment graded the land so Pittsburgh, Castle Shannon & Washington men could lay track. Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon trains rain the length of the entire line, from Finleyville to Pittsburgh. The companies honored each others’ tickets.

You know who was keenly aware that they were two different companies? The directors and stockholders of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railway. They were convinced that Hays was using his position to build up a second company and enrich himself at their expense.

They were 100% right. The problem was there wasn’t really a law against this sort of blatant self-dealing at the time.

The Pittsburgh Southern Railway Company

In 1878 Milton D. Hays moved one step closer to his dream when the Pittsburgh, Castle Shannon & Washington Railroad merged with the Washington Railroad. The combined Pittsburgh Southern Railway Company now had tracks running all the way from Pittsburgh to Waynesboro. Or rather, it would once he was able to connect the companies’ rail networks.

That was the final straw for the board of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railway.

They began openly criticizing Hays’ double-dealing in the press, hoping that might persuade him to change his ways. That didn’t work at all, so it was time for more extreme measures.

At the April board meeting they slammed Hays, removed him from his job as superintendent and gave it to D.Z. Brickell, and slashed his salary from $2500 to $500. Then they told him that the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon was terminating its joint operating agreement with the Pittsburgh Southern, effective in 30 days. That meant the Pittsburgh Southern would lose its access to the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon’s tracks, rolling stock, equipment, and employees.

The board seemed to think this drastic measure would force Hays to sell the Pittsburgh Southern to them, or at the very least force a merger between the two companies.

Milton D. Hays had other plans.

His immediate problems were simple: he had no rolling stock, and tracks that ended in Arlington, some 6.5 miles short of Pittsburgh.

The first problem was easily remedied. He was able to purchase a 24-ton locomotive from the Pittsburgh Locomotive Works, which had built it for a now-bankrupt client. He was also able to purchase passenger cars, a baggage car, and three flat cars from another railroad up near Erie.

Access to Pittsburgh was a trickier problem, but Hays had a solution. All that it required was for him to swallow his pride. He secretly approached one of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon’s hated competitors, the Little Saw Mill Run Railroad, and negotiated a deal which allowed the Pittsburgh Southern to use their right of way. That gave him tracks that ran along Saw Mill Run down to Temperanceville, just west of the city. All he had to do was lay three miles of track to connect the Pittsburgh Southern to the Little Saw Mill Run.

Except, well, this all created a third problem. The Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon and Pittsburgh Southern tracks were a narrow 40″ gauge. The Little Saw Mill Run tracks were an even narrower 30″ gauge. And the equipment Hays had just acquired ran on a 36″ gauge. The solution would be expensive but was also the only thing that could be done under the circumstances. Hays began laying a third rail so that his new cars could run on the existing lines, and started rushing to build that three mile extension.

The board of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon was aware of most of this, because some of the work was being done by their employees using their equipment. (Because Hays still had the rights to use them for thirty days and dammit he was going to use the hell out of them until those thirty days were up.) They didn’t know about the secret agreement with the Little Saw Mill Run, and were baffled that Hays was rushing to build a three mile extension that would end in the middle of nowhere.

Oh, I should probably mention the fourth problem, because this one’s a doozy.

The final connection between the Pittsburgh Southern and the Little Saw Mill Run would require trains to run over about a mile of track belonging to the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon. Hays claimed he still had the right-of-way over this track, though his enemies disagreed.

Hays had a plan for that too, though…

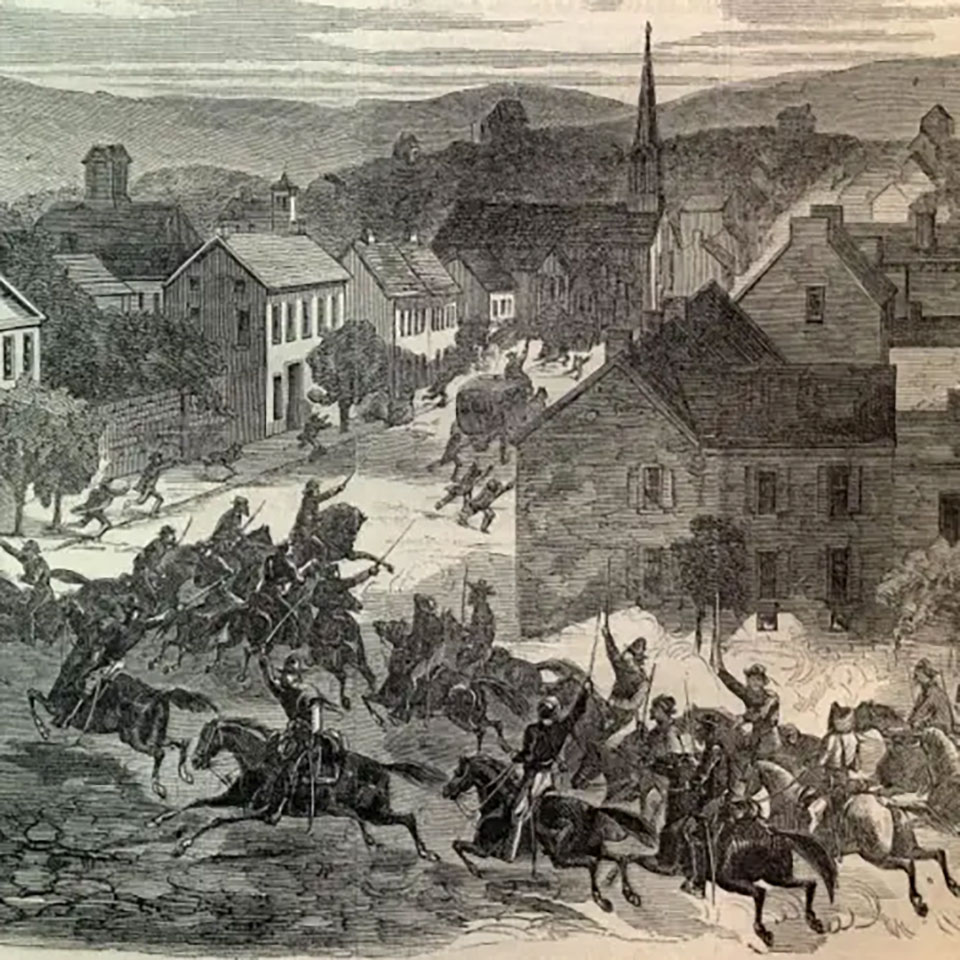

“…the feat was not accomplished without a personal encounter, the flourish of revolvers, and the shedding of some Pittsburgh Southern blood, small as though the quantity was.”

Pittsburgh Post

The Castle Shannon Railway War

On Sunday, May 12, 1878 — the day before the joint operating agreement was due to expire — Milton D. Hays assembled a crew of his own employees (not the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon’s), his brand new locomotive, and a flatbed car loaded with rails. The locomotive began pushing the railcar in front of it, while work crews laid down the third rail that would allow the 36″ locomotive to traverse the contested right-of-way.

In the middle of the morning, the directors of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon emerged from church services in Fairhaven to see the Pittsburgh Southern crew hard at work, and Hays personally supervising them. Suddenly they realized that he was not building a three mile spur to nowhere, but a connection to the Little Saw Mill Run.

Then they realized just how screwed they were.

They could not force the Pittsburgh Southern crew off the line; they still had the right to use it for one final day. They could not stop Hays from using their men and equipment, because he wasn’t using their men and equipment. They couldn’t even try to get an injunction to prevent him from laying down the new rail, because it was Sunday and the courts were closed.

They figured there was only one way to stop Hays: to physically prevent him from doing the job. Master mechanic Matt Rapp was ordered to strand one of their locomotives on the tracks in the path of oncoming work crew. Then Rapp set about spiking switches, loosening rails, anything he could think of that would slow Hays down.

It did not slow down the Pittsburgh Southern crew at all. Depending on which account you read, they either pushed the disabled locomotive ahead of them with their own locomotive, used some spare rails to gently lever it off the tracks, or forced it over a cliffside where it shattered into “a battered steaming mass of twisted steel.”

The two work crews were finally face to face. Rapp told Hays to stop, or else. Hays told his former employee that he was out of line and ordered him to back down. Rapp responded with the 1870s equivalent of “right back at you.” Angry words ensued.

Eventually Rapp got tired of yelling and threw a hammer at his old boss. It struck Hays right in the middle of the head, giving him a black eye and a bloody nose, and knocking him unconscious.

That did it. A brawl broke out between the two work crews.

Eventually the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon men realized they were vastly outnumbered and retreated. Though that realization might have been encouraged by one of the Pittsburgh Southern men drawing a revolver. (No shots were fired.)

By the time Hays came to about half an hour later, the dirty deed had been done. The Pittsburgh Southern had linked up to the Little Saw Mill Run.

Strategy Not Tactics

Milton D. Hays had won the battle. But would he win the war?

In the short term, yes. Brickell and the other directors were not sure how to proceed, and decided to leave the third rail in place until they got sound legal advice. (Probably a good idea, you never want to touch the third rail.) Hays was eventually conceded the right to use that last mile of track.

In the long term, no. Hays once again underestimated how much work he actually needed to do, and missed the scheduled July 4 opening of the Pittsburgh Southern by a month. In the meantime he had to fend off lawsuits from angry Pittsburgh Southern shareholders, who claimed he was failing to pay the dividends he had promised.

It is mind-boggling to think that during all of this Hays was still technically the president of the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon. The other directors moved to rectify this at the August 1 shareholder’s meeting, convening a commission to investigate Hays for misappropriating men, equipment, and money. And also for violating local blue laws, by laying his third rail on the Sabbath. Hays argued that he deserved a fair trial, not a kangaroo court run by a “cooked-up committee,” but had no good answer when he was asked if an accused criminal should be able to pick his own jury. He managed to delay his downfall until August 15, when he resigned to prevent the committee from releasing its report.

In December 1878 Hays was finally able to link up his northern and southern rail networks and had a single line running from Pittsburgh to Waynesboro. His triumph was short-lived. It quickly became obvious that the doubters had been right all along: connecting the two networks had cost an enormous amount of money, and the revenues were marginal at best. The Pittsburgh Southern never made a profit, and in 1883 was purchased by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad at the fire-sale price of $50,000. It continued to exist on paper for a few years as Hays was sued by suppliers and business partners he had stiffed… partners like the Little Saw Mill Rail Road, which had never been paid.

Over the years Milton D. Hays tried his hand at other businesses: ranching, lumber, more railroads… He even dabbled in novel-writing, though his two novels (My Grandfather’s Best Friend and A Parent’s Mistake) are some of the most boring, forgettable prose you’ll ever see. He made his millions, though his business practices continued to be questionable. He was constantly being sued for improper management, failure to pay dividends, patent interference, and more. He died in 1925 at the age of 81.

As for the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon, well, it went into receivership on April 25, 1879, partly due to competition and partly due to labor unrest in the local coal fields. It was able to reorganize and get back on a solid footing the following year, and continued to make modest profits until the 1890s, when the entire county went into a depression. To add insult to injury, it also took over the abandoned Pittsburgh Southern right-of-way.

In 1900 the company was purchased by Robert McDonald Lloyd of the Pittsburgh Coal Company, who discontinued passenger operations and focused exclusively on hauling coal. Eventually he leased the lines to the Pittsburgh Railways Company, which strung overhead power lines and laid another rail to accommodate its streetcars, which ran on a 62.5″ gauge. All service on the line was discontinued in 1914. The various inclines remained in service for a few years beyond that.

And yet…

In the early 1990s the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon line was completely refurbished by the Port Authority of Allegheny County, becoming the “Blue Line” of Pittsburgh’s light rail system. (Though it’s hard to call two measly trolley lines a light rail system, even if I do take it to work every week.)

So in a way, the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon is still going strong. You’d never even know that at one point, there was blood on the tracks.

Notes on Geography

Now, for Pittsburghers who are listening, I am going to give you the modern-day equivalents of where all the action in the story was taking place. You non-Pittsburgh folks can skip to the sources.

The Coal Hill Railroad ran down Warrington Avenue, its tunnel through Mount Washington was in roughly the same place as the Mount Washington Transit Tunnel, and the coal yard at its terminus was in the Station Square parking lot on Carson Street.

The Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon’s switchback started near where the Liberty Tunnels are today. The community of Fairhaven was located near the modern-day intersection of Saw Mill Run Boulevard and Library Road, meaning that if the Railway War happened today it would probably be seen by hundreds of people stuck in traffic at that terrible, terrible intersection. The line terminated near the present-day Arlington T stop on Mt. Lebanon Boulevard.

The Little Saw Mill Run Railroad ended in Temperanceville, now the modern-day West End.

And hey, here’s a fun sidebar. The picnic spot built by the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon was Linden Grove near Memorial Hall in Castle Shannon. At one point the Grove was a nationally designated historic place, but lost that designation when the owners decided to level the historic portions and turn the property into a parking lot/nightclub/nail salon/tanning salon. The more you know!

Connections

The Little Saw Mill Run Railroad was owned by the Harmony Society, a German-American religious order whose thrift, industriousness, and clever investments made them all fabulously wealthy… or would have if they werent’ also communists. For the tale of the Society’s rise and fall, listen to “Hold Fast What Thou Hast” and “That No Man Take Thy Crown.”

The South Hills coal mines serviced by the Pittsburgh & Castle Shannon Railroad were also rich targets for gangs, and eventually became the victim of the first armored truck robbery in America. We covered that tale in the “The Terror of Gillikin Country.”

Sources

- Aitken, David W. Jr. The Little Saw Mill Run Railroad: Its Life and Legacy. Self-published, 2003.

- Brennan, Joseph. “Pittsburgh Southern.” Columbia University. https://www.columbia.edu/~brennan/pitts/ Accessed 1/5/2025.

- Critchett, N.A. “Double Gauge.” Railroad Stories, Volume 18, Number 4 (November 1935).

- Hays, Milton D. My Grandfather’s Best Friend, or, No I Thank You; and A Parent’s Mistake: Two Romances of the Sixties. Milton D. Hays Company, 1908.

- Hilton, George Woodman. American Narrow Gauge Railroads. Stanford University Press, 1990.

- Michie, Thomas J. (editor). American and English Corporation Cases in the United States (Volume XVIII). Michie Company, 1903.

- Mierk. “Pittsburgh Light Rail: Functional and Unconventional.” Tram Review. https://tramreview.com/2021/03/pittsburgh-light-rail-functional-and-unconventional/ Accessed 1/6/2025.

- Mount Lebanon Fiftieth Anniversary, 1912-1962. Mt. Lebanon Township, 1962.

- Poor, Henry V. (editor). Manual of the Railroads of the United States. H.V. & H.W. Poor, 1878.

- Weilmer, Albert B. (editor). Pennsylvania State Reports (Volume 281). George T. Bisel Company, 1925.

- “Little Saw Mill Run Railroad.” Bridgeville Area Historical Society. https://bridgevillehistory.org/the-little-saw-mill-run-railroad/ Accessed 1/6/2025.

- “Milton D. Hays.” Carrick-Overbrook Historical Society. http://wiki.carrick-overbrook.org/Milton_D._Hays Accessed 1/2/2025.

- “The Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad (1871-1912).” Brookline Connection. https://www.brooklineconnection.com/history/Trolleys/PCSRR.html Accessed 1/2/2025.

- “The Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad Company.” Pittsburgh Gazette, 7 Oct 1871.

- “Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon narrow guage railroad.” Pittsburgh Commercial, 12 Oct 1871.

- “Pittsburgh and Castle Shannon Railroad Company’s Fair Haven plan of lots.” Pittsburgh Commercial, 25 Apr 1872.

- “Sale of lots at Fair Haven.” Pittsburgh Commercial, 29 Apr 1872.

- “City matters in brief.” Pittsburgh Commercial, 13 May 1872.

- “Castle Shannon.” Pittsburgh Gazette, 12 Sep 1872.

- “Castle Shannon Railroad extension.” Pittsburgh Post, 2 Feb 1878.

- “Our railroad extension.” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 19 Feb 1878.

- “A narrow gauge war.” Pittsburch Commercial Gazette, 13 May 1878.

- “Narrow guage war.” Pittsburgh Post, 13 May 1878.

- “A railroad riot.” Record of the Times, 22 Jun 1878.

- “What President Hays says.” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 25 Jun 1878.

- “Local news.” Monongahela Valley Republican, 27 Jun 1878.

- “The southern road.” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 19 Jul 1878.

- “The Castle Shannon Railroad.” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 2 Aug 1878.

- “Bouncing a president.” Pittsburgh Post, 2 Aug 1878.

- “Hays resigns.” Pittsburgh Post, 16 Aug 1878.

- “Castle Shannon Railroad.” Pittsburgh Commercial Gazette, 14 Sep 1878.

- “The narrow gauge.” Monongahela Valley Republican, 26 Dec 1878.

- “Milton Hays dies after long illness.” Pittsburgh Post, 27 May 1925.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: