Hold Fast What Thou Hast

the rise and fall of the Harmony Society (1803-1905), the richest communists in the world [Part 1]

For six months last year, I worked in Zelienople, PA. Each day on my way to work, I would pass a quaint little plot of land. It was square, maybe fifty or sixty feet on each side, surrounded by a low stone wall with an imposing stone gate. It looked for all the world like a cemetery, except that there were no grave markers at all. Just a well-maintained lawn.

One day, I noticed that there was a historical marker right next to the road. I pulled my car over to the shoulder and got out to read it, hoping it would provide some answers. It read:

Harmonist Cemetery. Burial place of Harmonist Society, 1805-1815. Graves were not marked. The stone wall was built in 1869, after the Harmonists had returned from Indiana and settled at “Old Economy” in Beaver County.

Well, I thought. That explains nothing.

So I set out to learn everything.

“I am a prophet and I am called to be one.” (1790-1804)

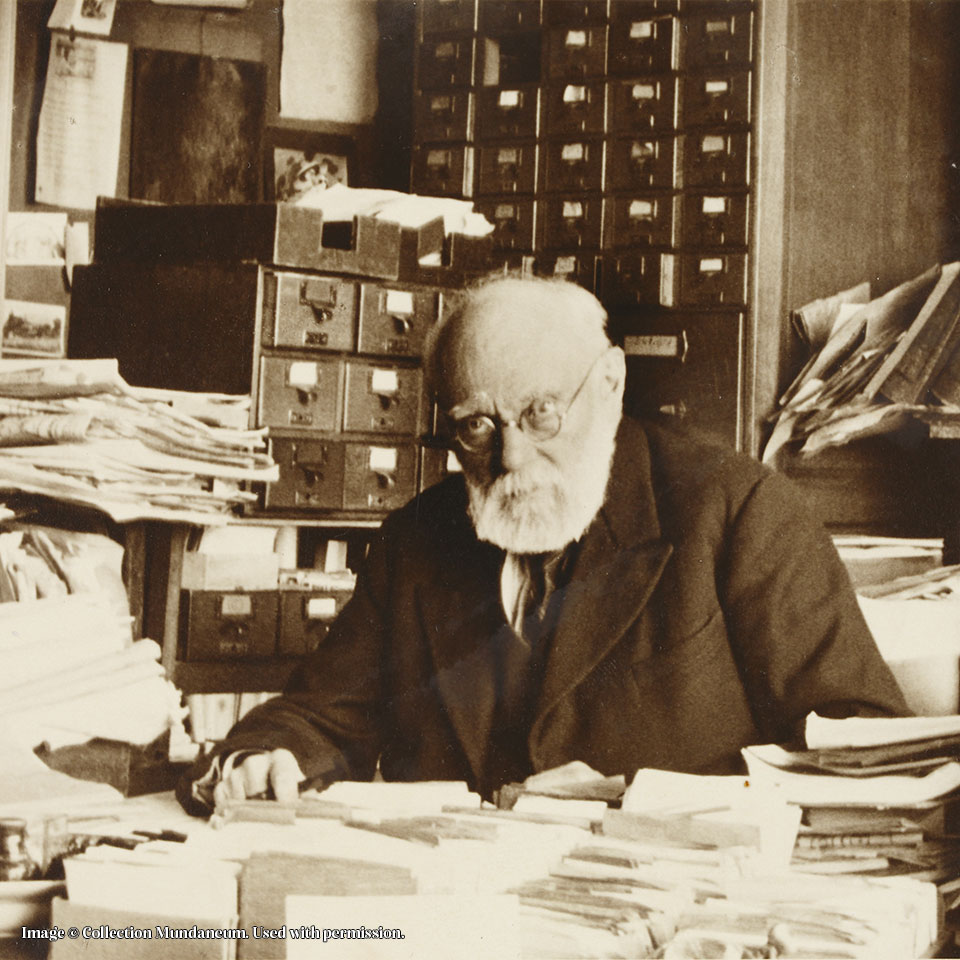

Johann Georg Rapp (George) was born on November 1, 1757 in the Duchy of Württemberg, near Iptinginen, about 15 miles northwest of Stuttgart. As a child he had received a solid German education before leaving to work on his father’s farm. In his twenties he married a neighbor’s daughter, Christina. The couple had two children, Johannes (John) and Rosina.

By all accounts he was a striking presence: six feet tall, stately, handsome and well-built with a big full beard and penetrating eyes. He was industrious, cheerful, kindly, plain-spoken, intelligent, and thoughtful.

And what he spent his time thinking about was the Bible. It had a lot to say about how to live your life. George was increasingly finding that living as the Bible directed was bringing him into conflict with the Lutheran Church.

At first, it was mostly small things, like failing to give priests the deference which they thought was due. Then George stopped going to mass, since he didn’t recognize the authority of the church, and started holding independent Bible study events at his farm. Soon he was a preacher, and eventually a prophet with numerous followers.

He wasn’t alone. There was something in the air in Germany in those days, leading many to question the legitimacy of the official state churches. These Separatist movements attracted thousands of followers, who only sought to practice the Christian faith in the way they thought most appropriate.

The Lutheran Church did not like any of this. “Hey,” they said. “You can’t just go reading the Bible and drawing your own conclusions from it! That’s not how the Protestant religion works!” They increasingly threatened the Separatists with legal action, including imprisonment, fines, and confiscation of their property.

George’s turn in court came in 1799, when he was arrested for purchasing a herd of pigs and driving them through the streets of town on Good Friday; essentially, violating Württemberg’s “blue laws.” The Church saw their chance, and had him fined and jailed.

Now, Duke Friedrich of Württemberg was a practical man. He found George to be defiant, but not disrespectful. He paid his taxes and was a good citizen. Why harass such a man, whose quarrel was with the church and not the crown? But the church’s persecution persisted, making Württemberg an unsafe place for George and his co-religionists.

The Separatists had options. There were religious enclaves where dissenters could worship freely, but for various reasons that did not appeal to them. They could leave the Duchy and go elsewhere in the Holy Roman Empire, though they’d likely find similar opposition to their religion wherever they moved. And moving across the border into godless revolutionary France was right out.

Instead, they looked across the Atlantic Ocean. In 1803, George Rapp set out for the United States of America to find a place where he and his followers could worship in peace.

Rapp had his eye on a prime plot of land where the Muskingum River meets with the Ohio, near modern-day Marietta. There were already people squatting on the land, which meant George would need a clear title to evict them. Ohio was not yet a state at the time, which meant the land had to be purchased directly from the federal government. So off to Washington, DC he went.

Rapp was not prepared for the speed of democracy. Congress took up his proposal, discussed it, and then… tabled it. For quite some time. It was frustrating, and Rapp wasn’t quite sure how to play politics in a language he could barely speak, in a culture he barely understood.

Then he got a letter from Germany. Four hundred members of his congregation were on their way. Like, now. Due to arrive any day. Rapp needed land, and he needed it fast.

Enter Baron Dr. Detmar Basse-Müller, a retired German diplomat and founder of the town of Zelienople, in Butler County, Pennsylvania. Basse was a weird fellow, who’d named a town after his beloved daughter and lived in a giant castle in the Pennsylvania woods called “Bassenheim.”

Zelienople was still in its infancy, so Basse had land to spare. He was happy to support his fellow countrymen and also to have some money to placate his creditors. He sold Rapp 500 acres of prime farmland on Connoquenessing Creek for $11,250, or about $250,000 in modern-day money.

George Rapp and his dream had a new home.

Brothers Dwelling in Unity (1804-1815)

Rapp rushed to Butler County to start clearing land for the commune he was now calling “Harmony” to honor the temporal and spiritual unity he desired for its residents. Work was barely underway when the first settlers starting arriving from Württemberg. Their first year was rough, but by the end of it, they had a solid foundation that they could build upon.

In February 1805, those early settlers formally signed the charter of the “Harmony Society.” So, what did the Harmony Society believe?

First, members were Christians, but they rejected established churches.

They were all expected to read and interpret the Bible on their own, though they held Rapp to be the final authority in such matters and responsible for all spiritual instruction. Unlike many cult leaders, Rapp was not considered to be divine or infallible, merely wise.

They believed in a single adult baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

Liturgically, they kept the Sabbath and celebrated a few additional holidays, including Christmas, Easter, a Harvest Festival, and “Love’s Feast.” They also celebrated the Founding of the Society, which was the only day they admitted new members to their commune.

Ideologically, they were pietists, holding themselves and others to a high moral standard. Forgiveness is divine, and given when asked, but still, better not to sin at all, eh?

They believed the ideal community was that of the primitive Christians described in the Acts of the Apostles, which meant living in small groups with communal ownership of all property and the fruits of all labor being shared equally. To that end, they lived together in multi-family homes, sometimes housing up to fifty people, and ate in communal dining halls. Their communist leanings even extended to their final resting places, which had no grave markers, because even that small gesture was tantamount to ownership of the land.

When someone joined, their property became the Society’s property and record was made of what they contributed. If a member left the Society (or was forced out), they renounced all claims to compensation or wages for their labor, but their initial donations were refunded to them in annual installments. If you hadn’t contributed anything, the Society’s leaders would give you a payout based on the length of your membership, the quality of your contributions to the Society, and your material needs.

Society members believed that they were living in the End Times, and interpreted current political events as a fulfillment of the prophesies in the Book of Revelation. Napoleon Bonaparte, of course, was the Antichrist – hardly the worst thing Boney’s been called, I suppose – and the Second Coming of Christ was imminent.

They saw their organization as the Church of Philadelphia mentioned in Revelation 3:

And to the angel of the church in Philadelphia write; These things saith he that is holy, he that is true, he that hath the key of David, he that openeth, and no man shutteth; and shutteth, and no man openeth; know thy works: behold, I have set before thee an open door, and no man can shut it: for thou hast a little strength, and hast kept my word, and hast not denied my name. Behold, I will make them of the synagogue of Satan, which say they are Jews, and are not, but do lie; behold, I will make them to come and worship before thy feet, and to know that I have loved thee. Because thou hast kept the word of my patience, I also will keep thee from the hour of temptation, which shall come upon all the world, to try them that dwell upon the earth. Behold, I come quickly: hold that fast which thou hast, that no man take thy crown. Him that overcometh will I make a pillar in the temple of my God, and he shall go no more out: and I will write upon him the name of my God, and the name of the city of my God, which is new Jerusalem, which cometh down out of heaven from my God: and I will write upon him my new name.

Revelation 3:7-12

As a result, they considered themselves the Elect, the chosen few who would be spared the tribulations of the End Times and be honored in heaven. Since the very nature of the Elect is that they are a very small, selective group, the Society did not evangelize. They were willing to take converts, if those converts could prove themselves up to the Society’s exacting standards, but they would not try to raise potential converts up to those standards, and did not hesitate to cast out those who could not meet them. Most visitors were turned away with polite deflections and reminders that the road to the heavenly kingdom was a hard one and not for everyone.

The ideal member of the Society had true harmony of mind, body, and spirit. At one point, when a professor came to the community seeking to soothe his troubled soul, Rapp put him to work hoeing potatoes to settle his “abnormally active” mind.

To keep the group selective and pure, they believed in isolating the Society from the rest of the world and its temptations. With very few exceptions, members of the Society were forbidden to interact with outsiders without explicit prior approval.

Those who violated the Society’s law or took more than their fair share would be ostracized at first. Habitual or serious offenders would be expelled from the Society outright.

Practically, the Society’s spiritual matters and local administration were handled by George Rapp. Their business, financial, and legal matters were handled by the industrious Friedrich Reichert, who became Frederick Rapp after George officially adopted him. Legally, though, the Society and all its money was structured as a trust administered by George Rapp.

It should be pointed out not everyone living in the community in 1805 signed the Articles of Association. They continued to live in the community, working side-by-side with members. The most notable holdout was John Rapp, the founder’s own son.

In 1807, the Society added a new tenet to their creed: celibacy. It started as a movement among the younger members of the Society, who had been reading the Bible closely and maybe paying a little too much attention to the Epistles of Paul. Once the young had the idea in their heads, though, Rapp saw little reason to displace it, and in fact encouraged it.

The proscription wasn’t always absolute. Married couples still lived together, and new marriages were performed, albeit infrequently. As the custom became ingrained, even married couples were expected to abstain from sexual relations.

To some, celibacy was a step too far. The young, in the grips of hormonal urges they could barely restrain, would frequently leave the Society to get married. Occasionally they would return begging forgiveness. In the early years, they might be warily accepted back into the fold. In later years, anyone who ran away to get married would be summarily expelled from the Society.

The practice was even referenced in Canto XV of Byron’s satirical Don Juan:

When Rapp the Harmonist embargo’d marriage

In his harmonious settlement (which flourishes

Strangely enough as yet without miscarriage,

Because it breeds no more mouths than it nourishes,

Without those sad expenses which disparage

What Nature naturally most encourages)—

Why call’d he ‘Harmony’ a state sans wedlock?

Now here I’ve got the preacher at a dead lock.Because he either meant to sneer at harmony

Or marriage, by divorcing them thus oddly.

But whether reverend Rapp learn’d this in Germany

Or no, ’tis said his sect is rich and godly,

Pious and pure, beyond what I can term any

Of ours, although they propagate more broadly.

My objection’s to his title, not his ritual,

Although I wonder how it grew habitual.

It seems funny and harmless now, but the adoption of celibacy was one of the decisions which ultimately doomed the Society. It would be decades before that became apparent, though.

The first couple of years in Pennsylvania were difficult for the Harmony Society. The Pennsylvania winters were harsher than the ones they were used to, and the harvests not as bountiful. They were frequently on the brink of starvation. But George Rapp kept them focused on the tasks at hand, and Frederick Rapp soon made friends and contacts in the local business community which helped keep them afloat during those lean years.

Soon, thanks to their industriousness, Harmony was a thriving community. They were trading goods all throughout the western Pennsylvania, including crops, textiles, and distilled spirits, for which they were widely known.

They did not get along particularly well with their neighbors. From the outside, their community looked less like “divine harmony” and more like a crazy cult full of credulous idiots. Instead of a wise elder, Rapp was seen as a tyrannical figure who worked his flock like dogs and hoarded all the proceeds for himself.

It didn’t help that Rapp often acted like an imperious monarch, directing every activity in town as he watched from a throne-like seat he had carved into a nearby cliff face. Society members couldn’t make their own case, either, since they spoke only halting English and shunned outsiders. And, of course, if you didn’t understand the Society’s worldview their actions were incomprehensible.

Once during the middle of winter Rapp went out to inspect a bridge the Society had built across the Connoquenessing. He was about halfway across the creek when the ice beneath him gave way. The other members of the Society rushed to help him out of the freezing water, but Rapp waved them off, claiming that the Lord would save him. Neighbors watching nearby from the shore jeered at his feeble attempts to save himself, encouraging the Society members to let him drown so they could take all his money for themselves. Ultimately, though, Rapp decided to stop waiting for divine intervention and consented to being pulled out of the river. The next Sunday blamed his near-death experience on his flock’s lack of faith.

In 1809 one Jacob Schaal, who seems to have been a disgruntled former associate of the Society, posted handbills all over the state accusing George Rapp of impregnating a Philadelphia prostitute and then procuring an abortion for her. The Society sued Schaal for libel, and won a judgment of $40 in their favor, but it was another blow to their reputation.

In 1812, a personal tragedy struck George Rapp when his son John died unexpectedly. It’s hard to tell from the sources, but it would seem he suffered a serious injury during an accident that occurred while moving grain into a silo. John was survived by his daughter Gertruda, or Gertrude, whom George took under his wing and doted upon.

The Society’s neighbors, however, told a different story. George, they said, had discovered that John was violating the Society’s policy of celibacy. And in the worst possible way, by discovering John in flagrante delecto. In a pious rage, the fiendish tyrant had his own son castrated. Only something went horribly wrong.

There’s almost certainly no truth to the castration story, but it circulated for years and dogged the Harmonists wherever they went. It was bolstered by John’s earlier refusal to sign the Society charter, which seemed to suggest some sort of friction between father and son.

At some point, some sympathetic soul, no one knows who, bought a gravestone for poor John. It’s the only marker in that weird little cemetery that first piqued my interest. If you visit today, you can find it propped up against a wall.

Of course, there were other things afoot in in 1812. Most notably, our country was at war with Great Britain in the imaginatively named “War of 1812.” During the war, several of the able-bodied men of the Society were drafted and ordered to Erie to defend our country from an anticipated Canadian invasion. They refused.

Now, Society members were not pacifists or conscientious objectors. They supported just and moral wars. Their refusal to serve was more akin to the position of modern Ultra-Orthodox Jews in Israel, who believe that their spiritual calling puts them above worldly concerns. We can debate the ethics of that later, but the end result is the same. The Society was now harboring draft dodgers.

Local courts acted swiftly and slapped the Society with a large punitive fine. The Society’s response was to make a payment of $640, half of what was owed, and roughly equal to the amount it would have taken to buy their way out of the draft in the first place. They thought the matter settled.

Magistrates thought otherwise, and sent armed debt collectors to confiscate Society property on multiple occasions. Each time there was nearly a riot, and the matter went to court. It was ultimately resolved in the Society’s favor, but helped crystallize something that the Society had been feeling for a while.

It was time to leave.

On June 10, 1814 a whole-column advertisement appeared in newspapers throughout western Pennsylvania, including the Pittsburgh Mercury and the Pittsburgh Gazette, offering the entire town of Harmony for sale at the bargain price of $200,000 ($3 million in today’s money).

It was all for sale. Every log house. The meeting house, the school house, and the inn. Cleared fields ready for planting, barns, and storehouses. The grist mill, the oil mill, the fulling mill, the dyer’s shop, the tannery, the saw mill, and the brewery. Oh, and a bridge over Connoquenessing Creek. The only thing that wasn’t for sale was the cemetery.

So, why did the Society decide to leave? Remember that they had never intended to settle in Butler County in the first place; it was Plan B when their attempt to acquire land in Ohio fell through. As a result, the property itself was unsuited to their needs in several key ways.

Most importantly, the Society was expecting to expand. They had started as a community of 400, but in just under a decade they had grown into a community of 800, and they were expecting hundreds if not thousands of their co-religionists to join them in the very near future. Harmony was not a place where that could happen. It was boxed in by Connoquenessing Creek on one side and by the growing community of Zelienople on the other, which left them no room to expand.

Pennsylvania winters were harsher than what the Society members were accustomed to back home in Swabia, and made it hard for them to grow some of their preferred crops, like grapes. The soil was too poor to support raising crops in the quantities necessary to support a larger colony, and the Connoquenessing did not run deep or swift enough to power the mills they would need. The Connie was also non-navigable, which meant it took too long to get goods to market.

Finally, the Society’s neighbors were too close for comfort, and they did not get along. For that matter, civilization itself, with all its temptations, was too close for comfort. (And, if you’re feeling pessimistic, all that temptation and forced social interaction made it too easy for dissenters to escape from Rapp’s tyrannical rule.)

Not surprisingly, the Society had difficulty finding someone to meet their $200,000 asking price and were forced to lower it in stages over the next few months. Ultimately, the entire town was sold for half that price, $100,000, to Abraham Ziegler, a Mennonite from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Plus an additional $1,600 for the durable goods the Society didn’t feel like taking them when they moved out. If Ziegler could get there before the Society’s neighbors picked over the town’s carcass. They had descended like carrion beetles as soon as members started moving out.

Well, I say half the price, but the Society transferred the land without requiring Ziegler to make a downpayment. This turned out to be a huge mistake, since Ziegler’s attempts to work the land failed. He made a few payments, but ultimately had to default.

Amazingly, the Society wrote off the entire sale as a loss, and they could afford to! They were flush with cash. And besides, they had their hands full in the new promised land: Posey County, Indiana.

In The Same Mind and Judgment (1814-1825)

When it became clear that it was time for the Society to move on, Rapp turned his eye westward to the American frontier.

He had his eye on a nice piece of land along the Wabash River in Indiana Territory. The climate and soil were more to his liking, and it was conveniently near the Ohio River, giving them easy access to markets all throughout the midwest. It was also not right on the Ohio, either, which placed them a healthy distance from civilization.

In 1814 Rapp purchased 24,734 acres of land along the from the Federal government, for the price of $61,050 ($120,000). Even after that extravagant purchase, the Society still had over $10,000 in the bank. He immediately sent a large cadre of workers to the new site to clear land and build dormitories. The new city was also to be called “Harmony,” which isn’t confusing at all, no sir.

It would turn out to be a difficult task. Pennsylvania was relatively civilized. Indiana was a true frontier territory and settling it would take real pioneer work. It didn’t help that the marshy riverfront land they’d chosen proved to be a breeding ground for mosquitos. That first summer they lost a good many men to illness and disease.

If anything, their new neighbors were even less friendly than their old neighbors. Pennsylvania had plenty of German and German-speaking settlers. Indiana did not, and its residents were suspicious and distrustful of anyone who didn’t speak English. The Society’s insular nature only worsened that suspicion. Local workers often tried to bilk the Society by slacking off or overcharging for work.

Not all their neighbors were bad, though. In 1817 Englishmen Morris Birkbeck and Richard Flower established their own commune upstream, simply called “The English Settlement.” They respected the Harmony Society’s example, and treated them with deference and respect, which was returned.

In fact, they soon attracted the notice of all sorts of fellow religious communitarians, including Zoarites, Hutterites, Mennonites, Moravians, and Dunkers. These groups would often write to Rapp, seeking advice and occasional financial support, which the Society was happy to give.

Other groups were more aggressive, most notably the Shakers. The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing found a lot to like in the Society’s philosophies, and repeatedly proposed a merger of the two groups. But they failed to spot the elitist aspects of the Society’s teachings, and how that might be undermined by suddenly admitting a large number of people to the ranks of the Elect. Rapp was polite in his refusals, but that didn’t stop the Shakers from proposing it again and again.

Politics was where they really got into trouble. Indiana Territory was finalizing its constitution and laws as it prepared for the transition to statehood, and the rough-and-tumble frontier politicians were afraid of the voting block the Harmony Society could form. The tried to diminish their influence by drawing a county line right through the middle of their settlement, and then boxing them further in by buying up all the land around them.

And, just in case those tactics didn’t work, they tried not-so-oblique threats. Here’s a letter they received from a local politician trying to discourage them from sending representatives to Indiana’s constitutional convention:

Honored Sir: Solomon says the wounds of a friend is better than the lies of flattorys of an enemy. Whether my Letter to you is for your Good or not time must determon first I beleave if your people Should Vote at the Approcheng Election Except yourself these votes will be rejected by they only Efect the County but I am of an opinion it will beget Grat inmity in this Territory Against your Society Which might be the Caus of your preveleag being much Certailed – I am of an opinion that this county or the territory would be willing to secure your libertys of giving your Society leberty to representing yourselves with one member but you will meet with opposition if you try to repersent this County, I am ures with due respect.

Alexander Devin

In spite of the hostility, Rapp could not be denied. Frederick Rapp, that is. His organizational skills were second to none, and even the haters had to acknowledge that they were useful. He became an important figure in Indiana politics, helping draft the constitution, choose the site of the state capitol, and draw up the state seal. He even found time to sit on the board of several local banks.

Frederick’s organizational zeal helped make the new Harmony even more successful than the old one. The Society was rolling in money, though individual members still continued to live like humble Swabian peasants, mystifying their neighbors. And their numbers were still small. As one wag put it, “The Society was making great progress in the manufacture of all articles with the exception of children.”

If their practical success had captured the attention of their co-religionists, their economic success soon caught the attention of economists and proto-communists in Europe, including notables like Welsh industrialist and utopian Robert Owen. These revolutionaries eagerly pointed to the Society as proof that their ideas were practical. Most of them failed to grasp the religious character of the Society’s charter, as well as their shared cultural background, which helped make success possible.

Things were going so well for the Society that in 1818 they burned their record books in a fit of pious ecstasy. Now, all the members were truly equal, and no one could say he had contributed more to the cause than their fellows. And of course there was never any way this would come back to bite them in the butt. Nosirree.

Of course, there were still problems. The Society ran into trouble with a local miller and decided he was too far away anyway, so they built their own mill and charged locals exorbitant prices to use it. In 1820 a hostile judge declared the mill to be public property and it was confiscated.

In 1823, they made a $5,000 loan to the state of Indiana, which was structured as a pre-payment of taxes. Indiana desperately needed the money and few other organizations could have spared it. The press painted the loan in the worst possible light, branding it as an attempt by the Society to purchase political influence.

Eventually, the Harmony Society were fed up. The people of Indiana clearly didn’t want them, and on April 11, 1824 they put the entire town up for sale just as they had done a decade earlier.

They quickly found a buyer in the aforementioned Robert Owen, who was looking for a place to test his own economic theories. An already-built town was perfect for his purposes. But he was suspicious of his good fortune, and asked why the Society was looking to sell. Rapp replied that with the hard work of building the town complete, there was less to do and idle hands made the devil’s work. It was time to move on and found a new town.

There was another reason which Rapp didn’t mention to Owen. In the early 1820s the Society had sent emissaries back to Württemberg, in an attempt to retrieve property and money that had been left behind during their initial migration, and to encourage any Separatists who had stayed behind to join them in America. What they found, though, was that their countrymen had moved on in the Society’s absence. Only 130 people made the journey to Indiana, and only a handful of those joined the Society. The land had been purchased with an eye towards supporting a community of thousands, but who needed 24,000 acres to support a community of only 1,000 people?

Working with Richard Flower of the English Settlement as his intermediary, Owen bought the town for a price of about $200,000. When the Society moved out, he rechristened it “New Harmony” and promoted it far and wide as a socialist utopia.

Owen looked at the the example of the Harmony Society and thought he could make it work without all that religious nonsense. Unfortunately, that “religious nonsense” proved to be the key to making the whole enterprise work. Owen’s “New Harmony” failed in less than two years.

By then the Society was well established in their new home. They’d moved back east, to Beaver County, Pennsylvania.

The Hour of Temptation (1824-1847)

For their new home, the Society had purchased a large plot about eighteen miles west of Pittsburgh near the confluence of the Ohio and Beaver Rivers. It was good land, well-situated for their needs. It was far enough away from large cities to be secluded, but close to a developing industrial center that provided availability to raw materials and financial services. It was right on a major river that made transport cheap and gave them easy access to markets throughout the midwest.

And while the locals might still be somewhat hostile, it was a genteel East Coast hostility they could live with as opposed to the roughneck frontier hostility they’d had to cope with in Indiana. There were the usual criticisms: they were a united voting block, Rapp treated them all like slaves, etc. etc.

Their new city was christened Economy, not because of any earthly industry, but because they were laboring to create “the divine economy,” the City of God on Earth that needed to be prepared for the Second Coming.

The move back to Pennsylvania brought a few changes. In New Harmony, the Society had started to shift from agriculture to industrial production of textiles and spirits. In Economy, that trend accelerated. The distillery was larger, as were the cellars needed to hold the whiskey, brandy, and “boneset cordial” that they were exporting all over the state. The cotton and wool mills were enormous and heavily mechanized, and the town plan included new industrial facilities that could make machines as complex as steam engines.

Steam power wasn’t the only thing the Society was experimenting with. In the early 1800s, America was obsessed with trying to make its own silk, and the Harmony Society was on the forefront of that movement. They produced some of the finest quality silk ever manufactured in the country, though they were never able to make it at scale or at economically viable prices. Gertrude Rapp turned out to have a particular genius for working with silk, and her silk embroidery won competitions all across the nation. Specimens of her work can be found in many museums, including the Art Institute of Chicago.

Small cracks also started to appear in the unity of the Society. The first small conflicts were naturally about money. George felt more money could be spent on the daily needs of the Society members, while Frederick felt that money was better off reinvested in in the Society’s industrial concerns. Since Frederick controlled the purse strings, he won these arguments, but they did start to sour the relationship between father and adopted son.

And then there was the Hildgeard Mutschler incident.

Hildegard was a beautiful young woman who had been born into the Society, one of the last to be born before the custom of celibacy became etched in stone. George Rapp doted on Hildegard, and eventually made her his laboratory assistant. They would spend hours in his workshop, alone, working on his botanical and alchemical research.

That the septagenuarian Rapp was spending his days hanging out with a beautiful young thing certainly raised some eyebrows. But he was getting old, and he needed an assistant, and she seemed to do the job well, so who could complain publicly?

Then Rapp started getting possessive. He exiled young Jacob Klein for getting inappropriately close to Hildegard. Many seemed to believe that Rapp’s motives in expelling Klein stemmed less from pious indignation and more from pure jealousy. They argued for Klein’s readmission to the Society, but Rapp could not be moved.

When Hildegard ran away to marry Conrad Feucht, the Society’s solicitor, Rapp was heartbroken. He wrote the pair letters begging them to come back, saying everything they had done could be forgiven. He even openly prayed for Hildegard’s return from the pulpit, which he had never done before for those who had left the Society.

Now no one could deny that Rapp was acting less like a distinguished patriarch and more like a lovesick schoolboy. Frederick and others even wrote a letter telling George to get it together and stop mooning over a girl fifty years his junior. It was a major blow to Rapp’s authority.

Conrad and Hildegard Feucht returned to the fold in 1833, after they had already produced several children. It took almost all of Rapp’s power and persuasiveness to get them readmitted, and even then the older members of the Society would always look upon the Feuchts with suspicion. This, too, would prove to be one of the events that would eventually lead to the downfall of the Society.

After the return to Pennsylvania, Rapp’s preaching had become increasingly more apocalyptic. It may have been a reaction to political developments in Europe, or a reaction to the increasing doubts among his flock, or even just an acknowledgement of his own advancing age. He became convinced that the “woman clothed in the sun,” a key figure in the Book of Revelation, had emerged or would soon emerge in eastern Europe, and he looked for a sign that would prove it.

On September 29, 1829, he got one.

On that day, the Harmony Society received a great letter secured with a magnificent golden seal which has to be described. It depicted the Earth, upon which sat a book inscribed verbum dei, which was being held open by a lion with one of his paws while he held a key with his other. Behind him rose a cross bearing various symbols, including an anchor, and above it the tablets of the Ten Commandments. This was all surrounding by lightning and arrows, and surmounted by clouds and the throne of God with symbols representing the Holy Trinity and the Gospels. Around the outside of the seal were crowns, and the phrase Beati qui servant mandata dei ut sit potest as eorum in ligno vitae et per portis intrent in civitatem dei. That’s a misquote of Revelation 22:14, “Blessed are they who keep the Lord’s commandments, for the Tree of Life is theirs, and they may enter in through the gates into the City of God.”

It came with a set of instructions asking for the letter to be read aloud at the next assembly of the Society. And it was.

The letter was dated July 14, 1829 and was handwritten in a beautiful script by one Samuel, the “consecrated servant of God, in the profane world still truly active Chief Librarian of the Free City of Frankfurt, Doctor philosophiae & theologia, Johann Georg Goentgen.” Samuel claimed to be transcribing the thoughts of the “the Ambassador and Anointed of God” and the “Lion of Judah,” another figure from the Book of Revelation who was deemed worthy to open the Book of Seven Seals containing the mysteries of God.

The Lion of Judah wrote with great familiarity about the Harmony Society, and seemed to be intimately familiar with its teachings. He chided them for straying from the true path and becoming obsessed with commerce and industry. He declared North America to be a desert of civilization, whose religious freedom allowed for the rise of both Christians and anti-Christs. He ended with a message of hope, nothing that the same freedom that gave anti-Christs the ability to take root also made it possible for the soil to redeemed, and encouraging the Society to return to their holy mission.

The fiery polemic had arrived at the right place in the right time. It vindicated the Society’s beliefs and bolstered their waning faith in their leader and the mission. On October 29, they sent a reply to the so-called Lion of Judah, inviting him to come to Economy.

For almost two years, they heard nothing. Then, on September 17, 1831 Rapp received a letter from Dr. Goentgen.

His highness, the Archduke Maximillian von Este, the Anointed of God of the stem of Judah of the root of David, had left Bremen with a retinue of 45 loyal retainers in July and had arrived in America on September 3. The Anointed did not wish to make himself known to the world, until he had a chance to meet with the Harmonists and see if they would follow the call of God. He had every hope the Society would prove themselves better than the faithless sheep of Europe, and together they would unite as one and exact God’s plan on Earth. Which the Anointed already had received directly from God, and which he would reveal when he reached Economy and assessed its citizens.

For the time being, for his protection and that of the Society’s, he was traveling incognito under the name “the Count de Leon.” Though I’m not entirely sure how incognito one can be when traveling with a retinue of 45 retainers.

So, let’s talk about the Count de Leon. As you may have guessed, he wasn’t actually a Count. Or an Archduke. He was, instead one Bernhard Müller, the son of two peasants in Kostheim (now in Germany, then in France). He claimed to be the son of the Italian House of Este, spirited away as a child and raised by peasants either to avoid embarrassing his parents, to avoid complicating an already complicated line of succession, or avert the fulfillment of an unspecified sinister prophecy. Or maybe he was just the illegitimate child of Prince-Bishop Karl Theodor von Dalberg, the Arch-Chancellor of the Holy Roman Empire. None of this was true.

Young Bernhard had been a tailor’s apprentice who ran away to join the circus. He wound up in Regensburg, where he became the pupil of English missionary William Sykson. In 1810 he wrote an angry letter to Napoleon predicting the emperor’s downfall, and after Waterloo he became convinced he was a prophet and the savior of the world.

Müller was an illuminatist, an alchemist, and a would-be prophet. It’s unclear exactly how much of his own lies he actually believed. It’s entirely possible he was genuine, though much of his behavior seems to be that of a classical scam artist. He had been chased out of several cities in Europe, including London, Dublin, and Offenbach, before settling once again in Regensburg where he gathered a small following.

In 1829, at the peak of his powers, he wrote notes to seventy two of the crowned heads and church dignitaries of the world announcing the Second Coming and the start of Christ’s promised thousand year reign. Every letter he sent was ignored.

Except for the one he sent to the Harmony Society.

When he received George Rapp’s reply, “The Count” and his followers sold all their worldly goods and made their way to the New World. Upon arrival, The Count wrote a letter to President Andrew Jackson, introducing himself as an exiled Belgian prince. He also circumspectly asked if he might be extradited back to Europe, implying that if that was the case AJ should do a brother a solid and let him know so he could head south to Mexico instead.

The Count’s “incognito” journey was widely reported in all the papers. He was not shy about telling people who he was, or why he had come to America, and where he was heading. The only thing he was evasive about were his religious motivations. Instead, he claimed he had merely come to buy 100,000 acres of land on which he could resettle his loyal followers.

When the Count finally made it to Economy in late September, sparks flew. The Count clearly considered himself superior to George Rapp, and expected to step in and take over the entire commune with no struggle. He settled into the town’s inn and started turning it into a sort of royal court.

For his part, Rapp was taken aback by the arrival of “The Lion of Judah” who was nothing like what he expected. Could he be a charlatan, or was this a test of his faith? Should he retire from preaching and turn his flock over to this charismatic stranger? He prayed as he had never prayed before trying to figure out his guest.

By the end of the year, Rapp had his answer. He knew the Count was up to no good, and moved to turn him out. He presented the Count and his retinue with a bill for room and board totaling $1,817.36.

The Count had not spent three months idly waiting for Rapp to turn over the Society to him. He had been studying his hosts, making friends, and identifying the fault lines that threatened to divide them. He knew there were members who wanted to leave the Society, but couldn’t bear the financial hardship that would entail. He knew there were members upset with their low personal standard of living, members chafing at the restrictions of enforced chastity, members upset with Rapp’s dictatorial leadership style.

When Rapp presented his bill, the Count presented a bill of his own. He claimed that Rapp had lured him to Economy under false pretenses, wasting his precious time. By his reckoning, the Society owed him $17,761.74 for travel expenses. But he was a generous man. He’d be willing to pay Rapp’s bill and settle up for a mere $15,944.38.

The end result of this back and forth was that Rapp was left spluttering with indignation while the Count and his allies holed up in the inn and fomented discontent in the community.

The Society took a few steps to address the dissenters’ complaints, like reducing Rapp’s power by instituting a Council of Elders, but it was too little, too late. In March, the protests turned violent. In the end, Rapp had no choice but to let the Count and his 250 followers leave. They represented nearly a third of the Society’s total membership, and they took $100,000 of the Society’s money with them.

They didn’t go too far. This new group, calling themselves the “New Philadelphians,” moved up the Beaver River and founded the city of “Löwenburg” near present-day Monaca, PA. At first, they rejoiced in their newfound freedom. Then, they slowly realized that it had been bought too cheaply. They sued for more, only to be countersued and harassed by the Society and its agents.

During these legal proceedings it came out that the Society had never been properly incorporated under Pennsylvania law. This allowed it to operate free of state interference, but it left it virtually unprotected from individual members looking to assert their rights.

Eventually, in 1833 the New Philadelphians decided to leave the Society behind entirely and relocated to Louisiana. It did not go well. The Count died in the disease-ridden swamps shortly after arrival, though his widow managed to keep the New Philadelphians going until 1871. Today their “New Jerusalem” in Louisiana is preserved as the Germantown Colony near Minden.

This was only the first blow to the Society. In June 1834, Frederick Rapp died after a long illness, concentrating both spiritual and temporal power in George Rapp’s hands. It was a seamless transition, since anyone who might have objected to this state of affairs had defected with the New Philadelphians. Rapp’s new powers were exercised almost immediately. In 1836 the Council of Elders and all members signed a new agreement to ratify the Harmony Society’s original charter, with one change. Now, anyone leaving was guaranteed nothing. If the Council of Elders were so inclined, they might pay the former members a pittance. But more often than not, they were not so inclined.

Then the Panic of 1837 hit, destroying the economy of the United States. Only the Society’s self-sufficient structure enabled it to survive. The resulting depression scared George Rapp so badly that he took half a million dollars off the Society’s books, turning it into gold and silver bullion which he hid beneath the floorboards of his cottage.

All the while, the Society continued to lose members, either due to old age or crises of conscience. When George Rapp passed away on August 7, 1847 the once-mighty Society had dwindled to a mere 288 members. Rapp had thought himself wise, but the Lord knoweth the thoughts of the wise, that they are vain.

This is part one of a two-part story. You can read part two at “That No Man Take Thy Crown.”

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

George Rapp thought Napoleon was the Antichrist and was obsessed with “The Woman Clothed in the Sun” from the Book of Revelation. He should have looked no further than British prophetess Joanna Southcott (“Exceeding Great”), who also thought Napoleon was the Antichrist and who claimed to be the Sun Woman.

The Harmony Society’s first home was in Butler County, PA, which is named for Revolutionary War hero General Richard Butler, who was laid low by “the white savage” Simon Girty in at the Battle of the Wabash River (“He Whooped to See Them Burn”).

Supplemental Material

Sources

- Arndt, Karl J.R. George Rapp’s Harmony Society (1785-1847) Revised Edition. Cranbury, NJ: Associated University Presses, 1972.

- Byron, George Gordon. Don Juan. London: self-published, 1824.

- Melish, John. Travels through the United States of America, in the years 1806 & 1807, and 1809, 1810, & 1811. Philadelphia: self-published, 1818.

- Nordhoff, Charles. The Communistic Societies of the United States. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1875.

- Postl, Karl (as Charles Sealsfield). The Americans as They Are. London: Hurst, Chance & Co, 1828.

- Wilson, William E. The Angel and the Serpent: The Story of New Harmony. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1964.

- “An Additional Source on the Harmony Society of Economy, Pennsylvania. https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/viewFile/3548/3379 Accessed 8/10/2019.

- “Bernhard Mueller.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bernhard_M%C3%BCller Accessed 8/10/2019.

- “George Rapp.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Rapp Accessed 8/10/2019.

- “Harmony Society.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harmony_Society Accessed 8/10/2019.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: