Wonder Marvelously

you will not believe, though it be told to you

There’s no better way to waste a lazy Sunday afternoon than to spend it fighting World War II all over again.

The infotainment industry will never let “the last good war” die. Any aspect of the conflict you can think of has been dissected and turned into a six-episode series that goes into excruciating detail and yet is still somehow maddeningly vague. Coming soon to the Style Network: the footwear of the western front, and how it won the war.

My personal favorites are the ones that deal with Wunderwaffen, the so-called “Nazi super-weapons.” There’s just something fascinating about watching the Germans spend so much precious time and money on moonshots like nuclear weapons, delta wing jet bombers, submarine-launched missiles, rocket-powered artillery shells and infrasound death rays. It’s even crazier that each time they came tantalizingly close to success only to fail as the Americans and Russians whittled away at their supply lines.

There were Allied super-weapons, too, and why not? It’s not like the Nazis had a monopoly on megalomania. The big difference is that some of ours (like the atomic bomb) actually panned out, and the ones that didn’t (like B.F. Skinner’s pigeon-guided missiles) were quickly abandoned.

The most out-there ideas came from the British, of course. Winston Churchill loved this stuff and constantly pushed for programs that the other Allies thought were borderline insane. Most of Churchill’s pet projects came straight from British Combined Operations Headquarters, especially after Louis, Lord Mountbatten was promoted to Chief of Combined Operations in October 1941.

It was clear to Mountbatten from early on that Britain couldn’t win the war with sheer numbers. It had to innovate its way to victory, and to do that he needed extraordinarily individuals unconstrained by convention who could think outside the box. Fortunately, he had a knack for locating and recruiting these individuals, tempered by what one his friends called “a total inability to judge men correctly.”

Under Mountbatten’s leadership Combined Operations HQ became a freak show, a dumping ground for eccentrics and weirdos who just didn’t fit into the regular chain of command. Some of the oddballs who passed through its doors included “Mad Jack” Churchill, already a legend for charging into combat swinging a claymore and playing the bagpipes; Hollywood actor Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.; not one but two race car drivers: international playboy Pedro Mones, the Marquis de Casa Maury and land speed record holder Sir Malcolm Campbell; yachtsman Herbert “Blondie” Hassler; and novelists Evelyn Waugh and Robert Henriques.

Biographer David Lampe later claimed that the only thing stopping Mountbatten from putting Lewis Carroll on his payroll was that Carroll was dead. Mountbatten’s own assessment was more direct. He called Combined Operations “the only lunatic asylum in the world run by its own inmates.”

The core of this asylum was a multi-disciplinary group of scientists led by J.D. Bernal and Solly Zuckerman, nicknamed “the Department of Wild Talents.” Now, you might be wondering what a molecular biologist and a primatologist had to offer the war effort, and you wouldn’t be the only one. Bernal and Zuckerman, though, proved to be worth their weight in gold. They were managers par excellence, able to get free-thinking individualists to collaborate and turn their pie-in-the-sky ideas into tangible reality.

The Wild Talents helped Blondie Hassler develop the commando kayaks of Operation Frankton, the raid that turned him into the Cockleshell Hero. They helped Hughes Hallett and others develop the artificial breakwaters and beachheads that made the D-Day landings possible, and the underwater pipelines that kept Allied forces supplied with petrol after the landings. Along the way they also laid the foundations of modern operational research, forever changing the way we fight wars.

But even Bernal and Zuckerman had their hands full dealing with Mountbatten’s most eccentric recruit.

Geoffrey Nathaniel Pyke

Geoffrey Nathaniel Pyke was born on November 9th, 1893 in London to Lionel Pyke, a prominent lawyer, and his wife Sara.

Lionel died when Geoffrey was only a child. Sara responded by having a nervous breakdown, making five-year-old Geoffrey the head of the household by default. He rose to the occasion, but resented his mother’s frailty and inability to adapt to her changed circumstances. As an adult he would shut her out of his life completely.

Geoffrey went to public school at Wellington, where he was mercilessly bullied for being an Orthodox Jew. The experience made him a fervent anti-anti-Semite and also a militant atheist. After Wellington, he went to Cambridge to study law. While there he earned a reputation as a stunningly intelligent thinker, not beholden to convention and capable of original insights and strange leaps of logic.

As Europe mobilized for the Great War, Pyke approached the editors of the Daily Chronicle and volunteered his services as a war correspondent, claiming that he could sneak into Germany and send back reports on the situation from behind enemy lines. The editors of the Chronicle accepted, thinking they had nothing to lose. A few weeks later Pyke crossed the border from Denmark to Germany thanks to a borrowed American passport and made his way to Berlin. He went to work, parking himself in cafés near military bases to eavesdrop on conversations and reading every newspaper he could get his hands on to see what he could glean from reading between the lines. That wasn’t much, because Pyke was arrested six days later when one of his trusted contacts turned out to be a German secret policeman. He was convicted of espionage and thrown into the infamous Ruhelben internment camp.

No prison camp could hold someone as clever and thorough as Pyke for long. After careful observation he realized that if he hid in the right place at the right time, the guards would not be able to see him because they would be blinded by the sun. So in July 1915 he did just that and walked out of the camp in broad daylight. For weeks he and fellow escapee Edward Falk eluded German forces as they hiked several hundred miles to the Netherlands and freedom. On their return to Britain they were hailed as heroes.

Pyke wrote a best-selling book about the escape, then took those royalties and parlayed them into a small fortune. As he would later describe it: “I went into the City and spent a day watching men entering and leaving the stock exchange. All of them appeared ineffably stupid, and many of them were my relatives.” He took up commodities trading and proved to be a quick study, at one point controlling a third of the world’s copper and tin supply.

In spite of this flirtation with hyper-capitalism Pyke was actually a dedicated socialist, who gave freely of his time and money to leftist parties and causes.

In 1918 he married Margaret Chubb, and the couple had a son, David, in 1921. Pyke decided his son deserved a better education than his own, free of close-minded thinking and anti-Semitic bullying. To that end he started Malting House, an experimental Monstesorri-style school where the kids called all the shots and punishment was forbidden. Descriptions of life at the school make it sound like a chaotic nightmare of liberal permissiveness, but the students loved it and it didn’t seem to hurt their test scores.

In 1927 Pyke over-extended himself when he tried to corner the copper market, only to get crushed by an American cartel. He lost everything and had to declare bankruptcy. He shuttered Malting House, abandoned his wife and family, and moved to a remote shack in Surrey where he lived in seclusion. For the next decade he lived off of the largesse of his friends and the occasional small editing job for various leftist newspapers.

When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936, Pyke volunteered his services to the Popular Front. He organized charity drives and logistics, finding novel ways to quickly and economically get the socialist forces the supplies they needed. He also turned his mind to solving technical problems and offering unsolicited advice to the Popular Front. He designed specialized motorcycle sidecars for carrying hot meals and pedal-powered trains. He even tried to save the PF money on medical supplies by teaching them how to use cheap peat moss instead of expensive bandages.

In early 1939 Pyke made a last-ditch attempt to stop World War II from breaking out by conducting a series of clandestine opinion polls showing that the German public was opposed to war. It didn’t work, but it got his name back out there. During the Blitz he also made headlines by writing articles arguing that the entire population of London could be relocated to man-made caverns beneath the chalk cliffs of Dover, with the idea that this troglodytic existence would protect them from German buzz bombs.

Articles like these brought Pyke to Lord Mountbatten’s attention, and on February 22nd, 1942 he arranged an interview with the reclusive genius.

Geoffrey Pyke did not make a great first impression on anyone. He was tall and gangly, with uncombed hair, a scraggly goatee, and thick glasses perched on an eagle-like beak. He wore old clothes for days on end until they were so rumpled and stained it was hard to believe they’d ever been washed or ironed. He looked for all the world like a hobo and not like Britain’s greatest independent thinker. He also had an enormous ego. His opening line was, “Lord Mountbatten, you need me on your staff because I’m a man who thinks. But my services will not be purchased cheaply.”

Mountbatten tested Pyke, asking him what could be done to stop the super-battleship Tirpitz, which was docked in Trondheim and allowed the Nazis to dominate the North Sea. Pyke thought for a minute, and then suggested that underwater pipes could be used to pump compressed air into the harbor, lowering the specific gravity of the water there until the Tirpitz was no longer buoyant. He demonstrated the basic principle with a bucket of water, a toy boat, and a lot of alcohol from Mountbatten’s liquor cabinet.

It was a horribly impractical idea, but it was exactly the sort of out-of-the-box thinking Mountbatten was looking for. He hired Pyke on the spot to be an idea factory for Combined Operations. The job came with the lofty title of “Director of Programmes.”

When MI5 and MI6 found out they flipped their collective lids. They were wary of Pyke’s leftist leanings and suspected him of being a spy for the Soviets. They wrote to Mountbatten, insisting that he could not allow someone like Pyke to have access to sensitive military information. Their warning was ignored, because Mountbatten had decided Pyke’s usefulness to Combined Operations outweighed any potential complications from divided loyalties.

Pyke and Mountbatten were on the same wavelength in many ways. His basic attitude was that, “The war can be won either by having ten of everything to the enemy’s one (including the ships to carry it), or by the deliberate exploitation of the super-obvious and the fantastic.”

To that end, he bombarded his fellows at Combined Operations with so many proposals that they were quickly overwhelmed. Soldiers, in particular, didn’t know how to react to a man who filled notebook after notebook with impractical ideas; took all of his meetings from his bed because he didn’t want to waste time getting dressed; and lived on a diet of herring and biscuits that made him unpleasantly fragrant. They complained to Mountbatten that his new hire was a nuisance, and Mountbatten’s only reply was “too damned bad.”

There’s no better example of Pyke’s “Pykeries” than his contributions to planning a nighttime raid on the oil fields near Ploiești in Romania. First he suggested deploying St. Bernards to ply sentries with brandy so they would be drunk when the airborne assault started. Then he suggested following up bombing with a ground assault with commandoes using all-terrain vehicles modified to sound like barking wolves to scare away Romanian soldiers. The piece de resistance was leaving behind a reserve force disguised as firemen, who could take Axis reinforcements by surprise and spray them with missile-firing hoses.

You can see why Churchill and Mountbatten loved this guy! These are ideas right out of a Tom Swift book, equal parts brilliant and insane.

Project Plough

Not all of Pyke’s ideas were quite as impractical.

When the Nazis captured Norway in 1940, Pyke had the insight that they were not really occupying the country in a traditional sense. Yes, they controlled key population centers and most of the transportation infrastructure, but they had no presence in vast swaths of the country. A vigorous resistance engaging in guerrilla warfare could force the Nazis to either commit more forces to Norway, weakening their positions elsewhere, or force them to quit Norway entirely and relinquish control of the North Sea.

The big problem was that the unoccupied parts of Norway that the resistance would have to operate from consisted largely of snowy mountains and tundra. How could they navigate this terrain?

Pyke had a ready answer: super-snowmobiles!

The key was the Armistead Snow Motor and its revolutionary screw propulsion system. If you could scale down the motor and weld it to a lightweight chassis, the resulting vehicle would be able to achieve speeds of 40 miles per hour, dashing in and out of areas before the Nazis even knew what hit ’em, enabling a few thousand commandos to have the same impact as a much larger army. Even better, since this was all based on existing technology, start-up costs would be minimal and production could begin almost immediately.

In 1941 Pyke forwarded this proposal to his Member of Parliament, who forwarded it to the War Office, who forwarded it to the Prime Minister’s Office, where it was spiked by Churchill’s science advisor, Lord Frederick Alexander Lindemann. Lindemann thought the idea was unworkable and that Pyke was full of hot air. I believe his exact words were: “Mr. Pyke is able to dash off reams of this pretentious nonsense. I suggest that he would be better employed annoying the enemy instead of us, by feeding their espionage with bogus information.”

Now that he was Director of Programmes, Pyke had the ear of Mountbatten and a direct line to the Prime Minister. He dusted off his old proposal and refined it to point out how these snowmobiles could be deployed in numerous theaters of war including Romania and the Alps. He also jazzed it up with a few fanciful flourishes, like arming the vehicles with “snow torpedoes,” a gizmo shaped like an insect’s ovipositor that could drop bombs behind it, and a novel design for those bombs that enabled them to latch on to tank treads. Just in case that wasn’t enough Pykery, he also suggested that parked snowmobiles could be disguised with an inflatable structure that mimicked an officers-only latrine, which rule-following German enlisted men would never dare to enter. Or, if that was too silly, maybe it could just be hidden under a tarp claiming it was a top-secret Gestapo death ray and verboten.

Needless to say Churchill and Mountbatten loved the idea, and their enthusiasm soon infected the Americans. The newly christened “Project Plough” was given the green light. Pyke and Brigadier Nigel Duncan were sent to the United States to supervise the design and construction of the snowmobiles.

Trouble started almost immediately. Duncan sidelined Pyke, seized control of the project, and began making poor decisions. First, he decided to replace the screw propulsion system with more conventional tank treads; they would be easier to manufacture but reduced the top speeds the vehicle could achieve. Then he allowed the Americans to rush the new design into production without first testing it. As a result the snowmobiles were plagued with several mechanical problems, and a few troubling design problems. Like, say, the inability to operate in non-Arctic conditions or fit into the hold of most cargo planes.

Pyke was horrified by what he saw as unnecessary changes to his perfect plan. He contacted Mountbatten and threatened to resign if Duncan wasn’t removed from the project immediately. He got his way.

Unfortunately, that meant the Americans now had to deal with Pyke. They had worked well with Duncan, who was a career military man. Pyke was something else. He was not a scientist or an engineer and had no technical qualifications whatsoever, but still acted like he knew everything. He was dismissive of everyone he thought of as his intellectual inferior, which is to say, almost everyone in America. If you argued with him he would yell at you and call you an imbecile, but if you pushed back he would crumble like a cookie and sulk. How do you deal with someone like that?

(It also didn’t help that MI6 had told the Americans that Pyke was a Soviet spy.)

To their credit the Americans initially worked with Pyke to roll back some of Duncan’s changes. Then Pyke started insisting that the project had to come to a halt so Combined Operations could conduct basic research into the nature of ice and snow. It was the last straw. The Americans contacted Mountbatten and threatened to shut everything down if Pyke wasn’t removed from the project. They got their way.

Project Plough went on without him. The resulting vehicle, the M29 Tracked Cargo Carrier, or “Weasel,” was a lot closer to Duncan’s vision than Pyke’s. Don’t get me wrong, it was a solid military vehicle, highly maneuverable, but hardly the game changer that had been envisioned at the start of the project.

Project Habakkuk

Pyke was supposed to return to London. Instead, he went AWOL. First he checked into the Mayo Clinic for exhaustion, then he took the train to New York and disappeared for several weeks.

He was already hard at work on his next big idea.

It had first come to Pyke while he was conducting research into snow and ice for Project Plough. An old National Geographic article about the North Atlantic Ice Patrol contained an anecdote about how icebergs were curiously resistant to even the most powerful naval ordnance.

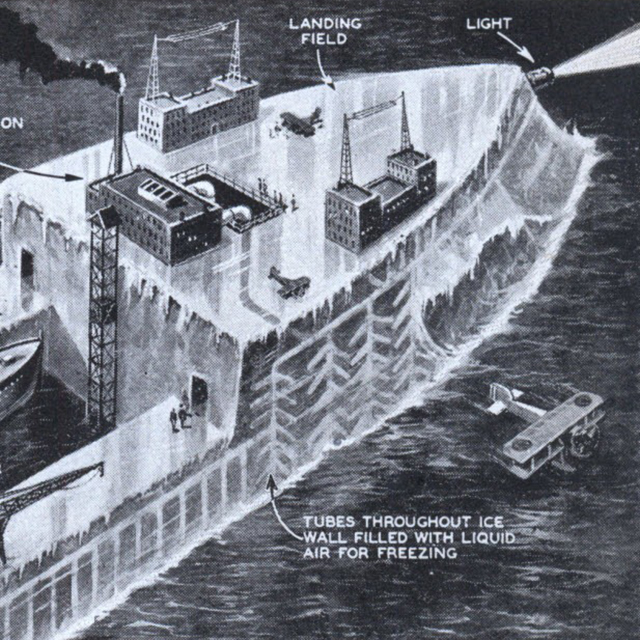

Perhaps, thought Pyke, this could be a solution to Britain’s problems in the North Atlantic, where ships were being sunk faster than they could be replaced. What if you could take an iceberg, hollow it out, and attach engines to it? It would be the perfect transport: far cheaper than building a similarly sized ship out of steel, impervious to the torpedoes of a German U-boat, unaffected by magnetic mines, practically unsinkable. Heck, if the iceberg were big enough you could even level off the surface and create a runway on top, turning it into an aircraft carrier.

He quickly dismissed the idea. Ice was tough in some ways but extremely brittle in others, so tunneling into an iceberg was likely to make the entire structure unstable. The ship wouldn’t have the maneuverability or stability to keep the men and cargo on board safe from the swells and storms encountered at Arctic latitudes. And the instant you steered it out of those latitudes towards an Allied seaport it would start to melt and break up.

Then Pyke stumbled across a passage in The Refrigeration Data Book of the American Society of Refrigeration Engineers that claimed frozen sand was actually several times harder than many types of rock. Intrigued, Pyke consulted with the book’s author, Professor Herman Mark of the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute. He asked the professor if it was possible to reinforce ice to make it stronger.

Mark laughed and told him he’d performed experiments along those lines a few years earlier while working at a Canadian paper mill. All you had to do was add some wood pulp or sawdust to the ice and it would turn hard as a rock. As a bonus the wood also acted as an insulator, vastly slowing the rate at which the ice melted.

Pyke refined his ideas throughout the summer, and in September 1942 he sent Mountbatten a new proposal, over 240 typewritten pages of pure insane genius. In his cover letter he confessed he was not entirely sold on the project himself, noting “It may be gold; it may only glitter. I have been hammering at it too long, and am blinded.”

He called it Project Habakkuk, after a minor prophet from the Old Testament.

Behold ye among the heathen, and regard, and wonder marvelously: for I will work a work in your days which ye will not believe, though it be told you.

Habakkuk 1:5

At its heart, the Habakkuk was still an aircraft carrier made out of ice, only now instead of being sculpted out of an iceberg it would be welded together from 40’ thick blocks of what Geoffrey was humbly calling “Pykrete.” Pykrete was practically indestructible; German torpedoes would only make small craters in the outer hull and any damage could be quickly patched with crushed ice and seawater. The whole ship could be kept at temperature with a simple refrigeration system made out of cardboard.

The Habakkuk would be half a mile long, 300′ wide and 200′ deep. That was nearly twice the size of the Queen Mary. It had more storage capacity than 80 liberty ships, and cargo could be frozen inside the walls of the ship for extra protection. Despite its immensity the Habakkuk could be constructed for only a few thousand pounds because it just was made from water, wood and cardboard.

What’s more, it could have a landing strip and enough hangar space to support 200 Spitfires or 100 Mosquitos along with their air and ground crews and several thousand support staff. This would allow the allies to have an airfield that could be deployed off of any coastal region in Europe.

Slowly deployed off of any coastal region in Europe, that is; because of its sheer size even twenty of the strongest electric motors, driving submerged propeller screws arrayed around the vessel, could only propel the Habakkuk at a pokey 7 knots. Due to its size, though, it could carry enough diesel fuel to give it a range of 7,000 nautical miles.

Just for good measure Pyke also went full Mr. Freeze, equipping the Habakkuk with deck cannons that pumped super-cooled liquid ice. He gleefully described their operation by imagining a raid on the Axis-controlled port of Genoa, with the Habakkuk first ramming and sinking enemy ships before turning its freeze cannons on coastal defenses and turning Nazi soldiers into living icicles.

Mountbatten loved it. He was all-in.

Pyke tasked one of his subordinates, Austrian biologist and glaciologist Max Perutz, to find the ideal ratio of water to wood pulp. Perutz spent weeks cooped up in a freezing room below London’s Smithfield Market and eventually declared that the ideal mixture was nearly 14% sawdust; when wet it had the consistency of freshly mixed concrete and when frozen it was stronger than steel.

Pykrete was everything they had dreamed of. It had a tensile strength of over 3000 psi. You could hit it with a hammer and it wouldn’t chip. You could shoot it with a bullet and it would stop it cold. You could bomb it, blast it, and set it on fire and it would still survive. And yet it could float and was still so ductile you could turn it on a lathe and work into any shape you needed.

Perutz had a sneaking suspicion it wasn’t all that, though. His earlier work had shown him the tendency of ice to severely deform when placed under strain, and an aircraft carrier would be under near-constant strain. He was confident, though, that the problem could be solved with further study.

Mountbatten revealed Project Habakkuk to the Prime Minister on December 5th, allegedly by barging into his private chambers and dumping a block of Pykrete into a freshly drawn hot bath. One hopes that Churchill was not in the tub at the time, if only so one does not have to imagine a naked Churchill.

Churchill, too, was all-in. Two days later he sent a memorandum to his staff, making Habakkuk a top priority.

The advantages of a floating island or islands are so dazzling that they do not at the moment need to be discussed. I attach the greatest importance to the prompt examination of these ideas, and every facility should be given to CCO for developing them.

The members of Churchill’s staff were all-in. Well, except for Lord Lindemann. At this point Lindemann was sick of Churchill ignoring his sound advice and decided to resign rather than work with kooks like Pyke and Mountbatten.

The Admiralty insisted on one small change to the design: the addition of a rudder. The ship didn’t need one: the multiple propellers provided redundancy, and allowed the ship to make tight maneuvers by selectively turning off the propellers on one side or the other, tank tread style. But the Admiralty insisted, and so a rudder was added.

Now, there was only one place in the British Empire where it was cold enough to make ships out of ice: Canada. To get the Canadians on board, Mountbatten gave them a tour of Perutz’s research facility. There they were allowed to go to town on blocks of Pykrete with a sledgehammer. They didn’t make a dent. One of them even drew a pistol and fired a shot at the Pykrete, which just ricocheted off. The Canadians were all-in.

In February a team of engineers from the Canadian National Research Council set up shop on the shores of Lake Patricia in Alberta’s Jasper National Park. A small army of conscientious objectors was conscripted to provide the necessary labor, while Mounties were tasked with keeping the site safe from prying eyes. Locals had no idea what was going on in their own backyard. Their best guess? The Allies were planning to build ice bridges to link the Aleutian Islands to Russia so material could be transported across the Pacific by truck.

The Combined Operations crew ran into problems almost immediately. At first, they had hoped that they would be able to make Pykrete by spreading sawdust on surface of the water, skimming it off as it froze and then laminating it into thicker blocks. This just didn’t work, so instead all the Pykrete had to be produced artificially in refrigeration plants.

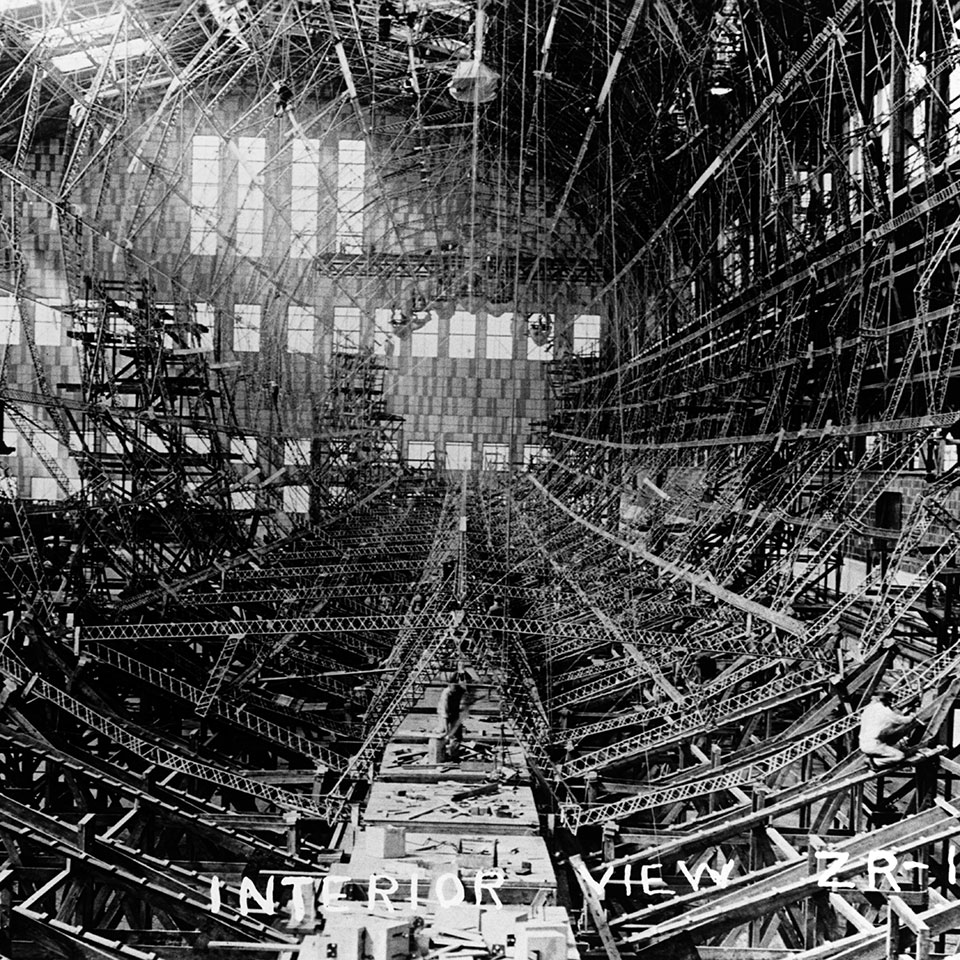

These manufacturing troubles also forced the team to drastically scale down the size of the prototype. The Admiralty had originally asked for a 1/10 scale model, but had to settle for a 1/20 scale model. (Mind you, that was still 60’ long, 30’ wide, and 20’ deep and weighed almost a thousand tons.)

Over the course of several week the Canadians built out the interior structure, including the keel and the refrigeration system. According to Pyke’s original design that system was supposed to recirculate chilled brine, but it was damaged in transit so the prototype would have to make do with cold air.

On the plus side, they discovered that blocks of Pykrete didn’t need to be welded together. If you just left them side-by-side they would eventually freeze together of their own accord.

In March Pyke arrived to supervise the end of construction and perform tests. Mountbatten also sent along Bernal and Zuckerman to keep Pyke on point, and to act as a buffer between the mad genius and the Canadians. It seemed to work, and Pyke was on his best behavior.

In early April the prototype was finally complete. It was sawed free from the ice “drydock” holding it in place and left to drift in the waters of Lake Patricia. Then the bombing tests began. The mini-Habakkuk performed admirably.

Canadians were now working on Project Habakkuk non-stop at every level.

- Scientists in universities across the country continued to study Pykrete to better understand its properties, specifically to see if the flow of the material would continue to be a problem. Eventually they realized that the flow was arrested at -15° C, which was well within the tolerance of the refrigeration system.

- An engineering company in Montreal worked on final design for the ship, figuring out the nitty-gritty details of its layout and support system. They even designed a mechanical system capable of making Pykrete in industrial quantities.

- The Canadian National Research Council scoured the country for the ideal construction site, eventually narrowing it down to Corner Brook, Newfoundland which was cold year round and had paper manufacturing plants where wood pulp could be sourced without raising suspicions.

There may have actually been too many people working on the project. During the week of March 29th, 1943 the daily Superman comic strip featured a plot where the Man of Steel confronted the latest Nazi menace: battleships disguised as icebergs! The ships in the comic bore little resemblance to the real Habakkuk, but military intelligence began to suspect that someone had been talking. Suspicions immediately fell on Pyke, because he had been in New York where the strip was produced and also because no one liked him.

Meanwhile, the prototype was faring surprisingly well. It passed durability tests with flying colors and the refrigeration system kept it in perfect form all summer, and it would have likely lasted longer had they not deliberately shut it off in August and allowed it to melt.

…the fig tree shall not blossom, neither shall fruit be in the vines; the labour of the olive shall fail, and the fields shall yield no meat; the flock shall be cut off from the fold, and there shall be no herd in the stalls…

Habakkuk 3:17

In August 1943 the British and Canadians finally revealed the existence of Project Habakkuk to the Americans for the first time.

First Churchill demonstrated the properties of Pyrkete to President Roosevelt by dumping small cubes into the hot water that had been brought for their tea. Then Mountbatten brought in larger chunks of ice and Pykrete for a more physical demonstration. He drew his pistol and shot the ice, which shattered. Then he shot at the Pykrete and things went pear-shaped. The bullet ricocheted as anticipated, but depending on who’s telling the story the exact outcome differs. So let’s just assume all the stories are true. If that’s the case, the bullet first nicked American Admiral Ernst King in the leg, grazed Lord Mountbatten’s stomach, and then narrowly whizzed past Sir Charles Portal of the RAF before embedding itself into a nearby wall. Meanwhile, two generals were so frightened that they dived under a table and collided, knocking each other out.

Needless to say, it was not the most effective demonstration.

The Americans were still curious. Some of their admirals thought a Habakkuk or two could give them a leg up on the Japanese. So they asked J.D. Bernal, as a representative of Combined Operations, to give them an analysis of the pros and cons. Bernal proceeded to give a quick summary of the project’s advantages, and then, unfailingly honest, gave a devastating run down of its disadvantages.

He mentioned the difficulties they had run into with developing construction methods and material flow, but pointed out that they had been overcome during the development process.

He conceded that individual Habakkuks would not require a lot of steel, but the refrigeration plants required to make them would — nearly as much steel as a conventional aircraft carrier. The plant itself would take months to construct, and wouldn’t be able to produce Habakkuks during the summer. This meant that the first vessels wouldn’t be ready for deployment until 1945.

There was also the matter of cost. The project was already significantly over budget, and the enormous start-up costs meant the first few ships would wind up cost nearly £6,000,000 each. At that price, they were hardly a bargain. In fact, they were far more expensive than a conventional aircraft carrier. Subsequent ships would be more cost efficient, but hopefully there wouldn’t be a need for subsequent ships. Unless the war went on forever.

Habakkuk’s specs hadn’t kept up with advances in military aviation. Its 2000’ runway meant it couldn’t handle most bombers and even fighter planes would need a rocket-assisted takeoff. Landing was an even bigger problem. In fact, it might be easier to just ditch planes in the sea and fish them out later than risk a landing on a Habakkuk.

Those same advances in military aviation meant that planes now had better fuel efficiency and larger fuel tanks. That gave them increased range and reduced the need for a mobile base in Europe.

There was also less of a need for invulnerable ships. The American entry into the war had decisively swung the Battle of the Atlantic in the Allies’ favor as German U-boats were overwhelmed by the flood of cheap and plentiful American ships. It turns out vulnerable ships were perfectly adequate, as long as you had enough of them.

Finally, there was Geoffrey Pyke himself. The Americans, soured by their experiences with Project Plough, didn’t like him. Unfortunately he was so critical to the project that it would be almost impossible to proceed without him.

The Americans thanked Bernal for his honest and frank assessment and passed. For the first time, someone wasn’t all-in on Habakkuk, and frankly, they were the only someones who mattered in the long run.

They weren’t the only ones. Once Churchill and the Admiralty realized the ships would cost far more than the initial estimate of a few thousand pounds or even a later estimate of £1,000,000, they too soured on the idea.

Mountbatten remained high on the project, for what little good that did. He had been promoted to Supreme Allied Commander in South East Asia, and no longer had a say in the day-to-day running of Combined Operations. His successors were less interested in zany super-science, and Project Habakkuk was formally abandoned in December 1943.

Pyke’s Final Years

Mountbatten’s promotion was the beginning of the end for Pyke’s tenure as Director of Programmes. He continued to bombard Combined Operations with crazy new ideas but without Mountbatten there to be his advocate, they increasingly fell on deaf ears. He was quietly let go in 1944.

When Pyke had been hired as Director of Programmes, he had been given the option to claim patent rights on anything he had invented after the war was over. In 1946 he wrote to the Admiralty asking if they would release the patent rights to Pykrete back to him so he could begin commercial exploitation of the material.

Now, Pyke’s claim to be the inventor of Pykrete is dubious at best — if anything, the real inventor would have been Herman Mark — but he had the right to ask for what was due to him. The Admiralty responded by releasing the patent rights to Pyke, but then immediately declassified the entirety of Project Habakkuk, including technical details, and publicized it in the newspapers.

It was a response driven by lingering spite and frustration with Pyke, and it just about ruined him. First, releasing the technical details made the patent effectively useless. Then, when the project was publicized in the papers, the general tone was one of mockery instead of wonder. “Look at the crazy idea these brainiacs wasted your taxes on!” Pyke’s reputation, already shaky, was basically destroyed.

He continued to apply himself to various projects, like promoting social justice and fixing the economy of post-war Europe, but he just didn’t have it any more. Oh, he still had the knack for identifying the real cause of every problem, but he could no longer make the intuitive leap to oddball and unobvious solutions. He resorted to recycling old ideas, like suggesting that post-war Europe could adopt pedal-powered trains as a cost-saving measure.

Eventually he could take it no longer. On February 21st, 1948 he got out of bed for the first time in several days, shaved off his beard, and then downed an entire bottle of sleeping pills. Then he went back to bed, got out his journal, and kept writing down his sensations until he finally passed out and died.

Pyke was privately cremated several days later. No memorial was held to mark his passing, and no gravestone was ever erected to mark his gravesite.

Years after his death, Pyke’s MI5 file was declassified and he could finally be cleared of charges that he was a Soviet spy. It turns out the Soviet spy was Pyke’s private secretary, which to be honest was probably just as bad.

There never was anything quite like Habakkuk. We did eventually get a sort of iceberg aircraft carrier in 1952 when the U.S. Air Force built an landing strip on an iceberg called Fletcher’s Ice Island, but it wasn’t really the same.

Project Habakkuk and Pykrete were quickly forgotten about except by naval historians and lovers of oddball esoterica, who saw it as a fun story about a wacky weapon system. For his part Mountbatten continued to insist it was a great idea that had only been killed because of politics. Others saw it as a story about the value of lateral thinking.

I think it’s probably better understood as a cautionary tale for visionaries. It may be true that if you dream it, you can make it. Just remember that in the end it still might not be worth the cost.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

Project Habakkuk was written up in our gospel, Strange Stories, Amazing Facts in the article “Iceberg Air Bases” (p. 195). We talked about our love of the good book in our teaser episode, “Strange Stories, Amazing Facts.”

J.D. Bernal didn’t make a personal appearance in Series 7’s “Moron or Madman,” but he can be numbered among the biologists who hesitated to speak out against the failures of Lysenkoism because of his own Communist leanings

Sources

- Blow, D.M. “Max Ferdinand Perutz, OM, CH, CBE, 19 May 1914 – 6 February 2002.” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Volume 50 (2004).

- Gucciardo, Dorotea. “‘Another of Those Mad, Wild Schemes’: Canadian Inventions to Win the Second World War.” Icon, Volume 14 (2008).

- Hemming, Henry. The Ingenious Mr. Pyke: Inventor, Fugitive, Spy. New York: PublicAffairs, 2015.

- Hodgkin, Dorothy M.C. “John Desmond Bernal, 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971.” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Volume 26 (November 1980).

- Lampe, David. Pyke: The Unknown Genius. London: Evans Brothers, 1959.

- McCloskey, Joseph F. “British Operational Reseasrch in World War II.” Operations Research, Volume 35, Number 3 (May-June 1987).

- Pickover, Clifford. Strange Brains and Genius: The Secret Lives of Eccentric Scientists and Madmen. New York: Plenum Trade, 1998.

- Ziegler, Philip. Mountbatten: A Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1985.

- Zuckerman, Lord. “Earl Mountbatten of Burma, K.G., O.M., 25 June 1900 – 27 August 1979.” Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, Volume 27 (November 1981).

- Strange Stories, Amazing Facts. Pleasantville, NY: Reader’s Digest Association, 1976.

- “Fletcher’s Ice Island.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fletcher%27s_Ice_Island Accessed 8/15/2021.

- “The Tale of Habbakuk: Ice Cube Carrier of World War II.” National Defense Transportation Journal, Volume 13, Number 1 (January/February 1957).

- “Allies planned aircraft carrier built of ice.” York Daily Record, 1 Mar 1946.

- “Allies planned artificial icebergs as aircraft carriers.” London Guardian, 1 Mar 1946.

- “Great problems of construction in Habbakuk.” Ottawa Citizen, 1 Mar 1946.

- “Allies planned big ice-ship airfields, ran tests in Alberta Rockies lakes.” Edmonton Journal, 1 Mar 1946.

- “Ice ship tests carried out here.” Edmonton Journal, 2 Mar 1946.

- “Canada had key role in Habbakuk project.” Windsor (ON) Star, 20 Mar 1946.

- “Habbakuk.” Vancouver (BC) Province, 13 Apr 1946.

- “Exercise Musk-Ox.” London Guardian, 22 Apr 1946.

- Johnston, Stanley. “Iceberg Carrier!” Chicago Tribune, 30 Jun 1946.

- “Our London correspondence.” Manchester Guardian, 6 Feb 1947.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: