Air Crash Museum

sorry, Meat Loaf -- two out of three ain't good

As soon as man slipped the surly bonds of Earth and danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings, his mind turned to the next great question: how can I use this amazing new invention to kill people?

The Montgolfier brothers made their first ascent in 1783, and less than a decade later the hot air ballon was being deployed… well, not on the front lines, but not too far from them! Admittedly, they were only being used to conduct aerial reconnaissance and transmit long-distance signals, but there was little else they could do. You see, in a balloon you can control your altitude, but lateral movement? That’s entirely up to the elements.

For more than a hundred years, that was the only practical application of air power. Even Henri Giffard’s invention of the blimp in 1852 really didn’t change anything. Sure, now you could control where you were going, but you still weren’t going to get there any time soon. A mobile target would be able to see you coming and have plenty of time to get out of the way.

That all changed thanks to one man: Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin.

Zeppelin had been an observer in the American Civil War, where he encountered balloonist John Steiner and made his first ascent. He loved the experience, but it was missing something: the ability to maim and murder his fellow man. The Count hit the drawing board and began drafting plans for blimps larger than a football pitch, supported by a rigid frame and hauling giant fans that weighed half a ton. These aerial monstrosities would be able to provide long-range reconnaissance, transport troops to otherwise inaccessible locations, and even bombard fixed fortifications.

He successfully flew his first dirigible rigid airship over Lake Constance in 1900, but it was still missing something. That missing piece finally arrived in 1909 when duralumin was developed by metallurgist Alfred Wilm. The aluminum/copper alloy was resilient and lightweight, exactly what Zeppelin needed to hold his rigid airships together without dragging them down.

The German army was impressed. They took twelve. The age of air power had begun.

Other European countries quaked in fear, especially Great Britain. Fortress Britain was no longer unassailable, and her defenders wet themselves in terror at the thought of a sinister “zeppelin” bursting out of the clouds and raining fiery death onto, say, Chesham. They scrambled to create their own airship program.

They needn’t have worried. When World War started in August 1914, the Germans had six zeppelins in active service. By the end of September, four of them had been shot down. It turns out a slow-moving vehicle operating within artillery range and held aloft only by a canvas bag full of highly flammable hydrogen gas was what you call “an easy target.” By the end of the war, every country had given up on the idea of military applications for airships.

Except for the United States of America.

It’s not entirely clear why we decided to go all-in on airships. To some extent, we were just playing catch-up: as a late entrant to the war, we skipped some of the lessons learned early on by the other major powers. There may have been some lobbying by the Aluminum Company of America, which was always on the prowl for new military uses for its signature product. And we may have just been trying to find some use for the United States’s vast natural deposits of helium, most of which lies under Federal land. What better use for all that safe, non-combustible helium than using it to float airships?

There was, as usual, a brief turf war between the Army and the Navy over which of them would have jurisdiction. In the end the Navy won out by arguing that airships operated and handled like oceangoing vessels, and besides, they had “ship” right in the name. As a consolation prize they let the Army have all the balloons and blimps they wanted.

R-38 / ZR-2 (1921)

After the end of the war the Navy went full steam ahead with plans to construct its first rigid airship, the ZR-1. That’s “Z” for zeppelin, and “R” for rigid, and “1” because it was the first.

The Navy had the know-how. The Allies had retrieved the wreckage of crashed zeppelins during the war, and intact samples of duralumin literally fell into their hands in 1916 when the engines of Germany’s L-49 seized up over Belgium. Three years of intense study had enabled them to reverse-engineeer most of the relevant technology.

What the Navy didn’t have were the facilities. America’s existing ballon- and blimp-making facilities didn’t operate on the scale necessary for the construction of airships. ALCOA knew how to make duralumin, but didn’t have the facilities necessary to make it in vast quantities just yet. As a consequence, the ZR-1 would likely not be ready until 1923 at the earliest.

An airship program without airships would just not do, so the Navy tried to buy an existing airship. During the war it tried calling dibs on several zeppelins that wound up being destroyed before they could be captured. When the Germans were forced to liquidate the rest of their airship fleet, the Navy tried to acquire sever but was outbid by the other Allies.

In the end, they solved their problem by purchasing an already-under-construction airship from the British. The British Air Ministry was relieved. They had commissioned the R-38 before the war, but now they were having buyer’s remorse due to the enormous cost.

The costs were enormous, mind, you, because the R-38 was simply enormous. It was over 700′ long and 85′ in diameter. It held 2,720,000 cubic feet of gas providing over 45 tons of disposable lift, and could achieve a cruising speed of 70 mph — super slow for a plane, to be sure, but pretty damn fast for a boat.

The Americans took over the project and re-christened the airship the ZR-2.

According to the project’s original timeline, construction would be finished by Spring 1921 and would be followed by several weeks where American aeronauts would receive flight training from their British colleagues. Then ZR-2 would cross the Atlantic in July, spend the rest of the Summer flying back and forth across the country on a publicity tour, and enter full service in the Fall.

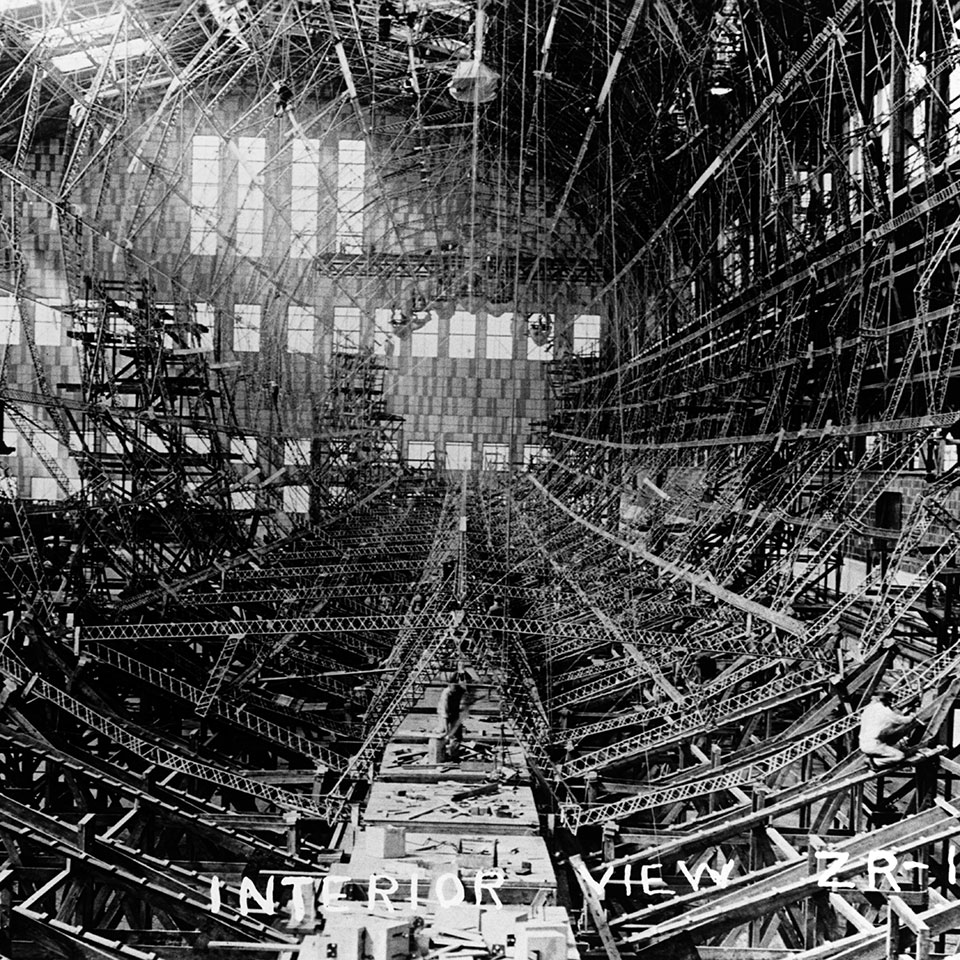

In anticipation of the ZR-2’s arrival, the Navy began construction of an airship hangar at the Naval Air Engineering Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey. Hangar No. 1 was the largest aircraft hangar the world had ever seen — heck, at the time it was the largest single interior room the world had ever seen, capable of housing two ZR-2s side by side with room to spare. And it was only the beginning. The Navy envisioned it as the first in a series of air bases and “mooring masts” spanning the country, at strategic waypoints like Boston, Cleveland, Chicago, St. Louis, New Orleans, Omaha, Denver, El Paso, San Diego, Seattle, and San Francisco.

By March 1921 Hangar No. 1 was complete. Unfortunately, the ZR-2 was way behind schedule and over-budget due to labor unrest, which was conveniently blamed on “Bolshevism.” In attempt to get back on track and minimize delays, the Navy cut back on a lot of the scheduled safety and quality control checks. The Air Ministry, which was trying to keep its costs down, didn’t push back.

On August 23rd, 1921 a multi-national flight crew took the ZR-2 out for her final test flight. The airship took off from its base in Bedfordshire and was afloat for a day and a half. At 5:37 PM on August 24th the ZR-2 was over the city of Hull in Yorkshire, when the flight crew decided to put the airship through a series of stress tests. While she was moving at maximum speed at an altitude of 2,500 feet, they slammed the rudder hard to port, then hard to starboard, then back again.

Two problems became immediately apparent. The first problem was that the airship’s frame was not designed for maneuvering at low altitudes; rapid maneuvering could only be attempted at high altitudes where the thin atmosphere meant less aerodynamic stress. The second was that reverse-engineered duralumin was not quite as strong as its German counterpart.

A girder buckled amidships, just behind the rear engines. The frame crumpled, severing fuel lines and spilling petrol all over the hot engines. That set off an explosion in the fuel tank, which in turn set off a bigger explosion in the air bags. The resulting shockwave shattered windows for miles around.

The ZR-2 split in half and began plummeting towards the earth, nose down. Her commander, Flight Lieutenant Archibald Herbert Wann, at least had the presence of mind to release ballast and open the throttles, steering the airship away from residential areas and toward the River Humber. Most of the terrified crew leapt from the flaming wreckage without parachutes and died on impact when they hit the river. The forward section with the control car plunged into the river. The rear section, buoyed by the remains of a gasbag, made a gentler landing on a nearby sandbar. Of the ZR-2s 49-man crew, only five men survived the crash: four airmen who had been in the tail section, and Lt. Wann, who who had been at the controls.

From beginning to end, the whole disaster had taken about five seconds.

At first the military blamed the disaster on a freak lightning strike, but it wasn’t long before the truth came out.

The ZR-2’s duralumin frame had been a continual source of problems. Several girders had also buckled during a test flight on July 17th, and the only follow-up had been a series of quick patches. The girder that had buckled during the ZR-2’s final flight was one of the patched girders. The whole thing was summed up succinctly by Lieutenant Wann: “She was never any good, only we weren’t sure.” It soon became clear that minimizing delays and cost overruns were more important to the Navy and the Air Ministry than doing things correct.

It was not the Navy’s finest moment. They had spent $14 million on the airship program — $5 million on Hangar No. 1, and the rest on the design of the ZR-1 and the construction of the ZR-2 — and now all they had to show for it was a big empty building and sixteen dead Americans.

ZR-1 “USS Shenandoah” (1923-1925)

Well, if there’s anything you count on, it’s that the once the military has committed itself to a course of action it’s going to stick to it, consequences be damned. Rear Admiral William A. Moffett of the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics assured the public that work on the ZR-1 would not stop: “There won’t be any fizzle with the ZR-1. We are going to make a success of it.”

Work on the ZR-1 continued as planned.

At least once the money started flowing again. Congress had responded to the ZR-2 crash by slashing the budget for Naval aviation. Admiral Moffett tried to change the legislature’s mind, but had difficulty making his case when when the US Army’s semi-rigid Italian airship, the Roma, took a nosedive into some power lines near Norfolk, VA and exploded, killing 34 crew members.

Eventually he managed to pry open Congress’s wallet and the ZR-1 began to take shape at the Naval Aircraft Factory in the Philadelphia Navy Yards. She wasn’t quite the monster the ZR-2 had been, as her builders had chosen to copy the design of the German L-49 as closely as possible. She was only 680′ long, 78′ in diameter, and carried 2,155,200 cubic feet of gas. Her smaller size meant that she only had a disposable lift of about 28 tons, but also meant she could use smaller 320 horsepower engines to achieve the top speed as the ZR-2.

Amazingly, the ZR-1 was completed on-schedule in Summer 1923. During September she made a handful of shakedown cruises, flying from New York to Philadelphia and back. On October 10, 1923 the airship was officially christened the USS Shenandoah.

She was the flagship of the Navy’s airship fleet — indeed, she was the only ship in the Navy’s airship fleet. Now the Navy just had to figure out what to do with her. In six years of planning they had yet to come up with a better idea than “aerial reconnaissance,” and there’s not much of a call for that in peacetime.

(I mean, okay, this is the United States we’re talking about. Even when we’re not officially at war with someone, we’re usually sending troops invade some country in Central America or the Caribbean that’s elected a Communist government, or somehow managed to piss off the United Fruit Corporation, or maybe eats their bread with the butter side down. Still, conflicts of that scale rarely need a ton of reconnaissance, and there’s no way the Navy was going to risk their only airship by deploying it to a war zone.)

At least the Navy was working on the uniqueness problem. They were busy drafting plans for a new generation of airships, and had commissioned a zeppelin right from the source, the Luftsschiffhau Zeppelein Gesellschaft, with an expected delivery date of Summer 1924.

As for the Shenandoah, the Navy first considered sending her on a scientific expedition to the North Pole, which had only been reached once and had yet to be reached by air. Planning for the expedition was well underway in December 1923 when the a French zeppelin, the Dixmude, exploded off the coast of Sicily, forcing them to shelve those plans.

While they tried to figure out what to do next a sudden storm hit Lakehurst in January 1924, tearing the Shenandoah free of her moorings and blowing her all the way to Staten Island. She had to be grounded for several months for while repairs were made. A full inquiry blamed the accident on lax safety procedures, so her captain was relieved of duty and replaced with the service’s most experience aeronaut, Captain Zachary Lansdowne. The new skip ran a much tighter ship and made a number of significant improvements immediately, including drafting a entirely new manual on airship operation and safety.

Once the Shenandoah was back in ship-shape, the Navy revealed her new, drastically scaled-back mission: a public relations tour of the United States. (Ah, yes. Join the Navy, see Dubuque.) The Shenandoah left Lakehurst on October 7th, 1924; flew across the continent to California, then up to Washington, and then back to Lakehurst. Huge crowds assembled to see her wherever she went — and for many of them it was the first time they had ever seen an airship, rigid or semi-rigid.

The Shenandoah returned to Lakehurst on October 25th, after 235 hours and 1 minute of continuous flight time, to discover that she had a new roomie in Hangar No. 1: the ZR-3 had finally arrived from Germany. At 658′ long the ZR-3 was a little shorter than the Shenandoah but dwarfed her in every other way: she was 90′ in diameter, carried 2,764,460 cubic feet of gas, and had 400 horsepower engines that could propel her at 75 mph. On November 25th she was officially christened the USS Los Angeles.

Throughout the Spring and Summer of 1925, the Shenandoah and the Los Angeles participated in fleet exercises designed to test not only their capablilities, but the design of a shipboard mooring mast that could extend their functional range. In the Fall, the Shenandoah was sent out on another publicity tour of the country, where it would make flyovers of air shows and state fairs.

The Shenandoah left Lakehurst on September 2, 1925 bound for St. Louis. As she flew over western Pennsylvania that evening, she spotted thunderclouds to the south and made some course corrections to avoid them. Then she spotted more thunderclouds due west, and corrected once again. Then, she spotted thunderclouds to the north and east. Captain Lansdowne realized, too late, that he had steered into the convergence of two powerful storm fronts.

The Shenandoah started rising rapidly in spite of all attempts to cleave to the ground; at one point she was yawed down 18 degrees and still somehow rising. Captain Lansdowne ordered her due south, but only wound up steering her into even more ferocious updrafts. The airship was buffeted to 3,000 feet, and the crew breathed a sigh of relief as things seemed to die down. Then the winds picked up again and she began ascending at an incredible speed — over 1,000 feet per minute — with her nose pointed almost straight up.

At 6,200 feet the ascent finally came to an end. Unfortunately, that was because the crew had been desperately venting gas in an attempt to level off. Now, with under-inflated gas bags and no updrafts to buoy her, the Shenandoah began plummeting at at a rate even faster than she had been ascending — 1,500 feet per minute. In a vain attempt to keep her aloft the crew dumped more than 4,000 pounds of ballast and made preparations to start dumping fuel.

Crosswinds hammered the Shenandoah, forcing her nose to port and her tail to starboard. With a terrible shriek she tore asunder. For a brief moment the two halves were still held together by dangling control cables and fuel lines, and Captain Lansdowne told everyone in the control car they were free to abandon ship if they so desired. Only two officers took him up on it. The rest remained dutifully at their stations, trying to save the airship and the lives of every man aboard.

But it was too late. Seconds later the control car broke free and smashed to the ground, killing the eight men inside. Moments later two men fell to their deaths from the radio room, followed four more from the forward engine room. A section of the bow, attached to an intact gas bag, broke off and soared up to 10,000 feet with seven men still inside. At least the 22 men astern were lucky. The 425′ long tail section slammed to the ground hard — but safely — in a farmer’s field outside the town of Caldwell, Ohio.

It was 3:45 AM on September 3rd, 1925.

Three hours the bow section drifted back to Earth some 12 miles away. Lieutenant Colonel Charles E. Rosendahl had managed to control its descent by carefully venting the gas bag. The seven sailors inside were worse for wear, but they were alive.

It could have been so much worse. Had the Shenandoah been filled with hydrogen instead of safe, non-combustible helium, the entire crew might have been lost instead of just fourteen men. That was cold comfort to the survivors, who saw little to be grateful for as they surveyed the wreckage of the once-majestic airship.

As word of the crash spread, Caldwell was deluged with curiosity seekers. Local farmers saw an opportunity to make a quick buck, charging 25¢ a head to drive looky-loos out to the remote crash site, and selling water and lemonade for 10¢ a glass. That was morbid, but downright quaint compared to the legions of souvenir hunters and looters who quickly descended on the wreck. These ghouls stripped the Shenandoah of everything of value: canvas and cloth from the gas bags, duralumin struts, instruments from the control car, even the personal effects of the deceased. The local chapter of American Legion put on their old uniforms and went out to guard the crash site until the Navy could arrive, but it was too late. Captain Lansdowne’s cap wound up on display in a Wheeling storefront, and rumors circulated that his wedding band had been wrenched off his finger. Goldbeater’s skin from the gas bags was gathered up by a tailor in Marietta, who turned it into rain ponchos he tastefully called “Shenandoah slickers.”

An official investigation placed most of the blame for the accident on Captain Lansdowne’s decision to steer the Shenandoah directly into the storm front. (In his defense, at the time the country did not have a reliable national weather service.) Testing by ALCOA also revealed corrosion on the airframe, which suggested a flaw in their treatment process. The Navy also came under fire for modifying the safety valves on the airship to make it harder to vent gas in an attempt to conserve expensive helium.

ZR-3 “USS Los Angeles” (1924-1932)

In the wake of the accident the public began to sour on the rigid airship program, which as far as they could tell was just an extra-expensive way to kill our boys in uniform during peacetime. Even military brass came out against the program — most notably, Colonel Billy Mitchell, America’s foremost advocate of air power, whose opposition to the program was one of the factors that lead to his court-martial later that year.

The program still had its supporters, and it helped that most of them were admirals in the Navy. That group included Admiral Moffett and, astoundingly, Lieutenant Colonel Rosendahl, who would go on to become America’s biggest advocate for lighter-than-air aviation. The yeas won the day, and the program continued apace.

A much slower pace. Helium was expensive, and the Navy couldn’t afford enough gas to float two ships simultaneously. With the loss of the Shenandoah they now had to wait for their strategic reserves to build back up before resuming operations with the Los Angeles.

Since the Navy was once again reduced to a single airship, they became far more cautious about her deployment. They were right to be cautions, because whenever the Los Angeles participated in mock combat she performed terribly. The airship was also constantly plagued by embarrassing minor accidents. Most notably, in 1927 she was caught by a gust of wind that lifted the tail section, yawing her to 85 degrees down. (There’s a photo of incident on her Wikipedia page — go check it out, it’s pretty frightening, especially when you remember the crew was on board.)

Eventually, the Los Angeles became a literal public relations vehicle, a showcase for American power and ingenuity. Or rather, German power and ingenuity, since they were the ones who built her.

ZMC-2 (1929-1941)

Even if the Los Angeles was largely out-of-commission, the Navy was still committed to developing new airship designs for the future of warfare. In 1929 they contracted the Aircraft Development Company of Detroit to build an experimental ship, the ZMC-2, with the “MC” standing for “metal-clad” and the “2” standing for I don’t know what because there was no ZMC-1.

There were no duralumin frames or canvas-covered leather to be found on this revolutionary design — instead, the entire gas bag was made out of paper-thin sheets of Alclad, a corrosion-resistant aluminum alloy. It was incredibly durable… and also heavy as hell. To keep the weight down the ZMC-2 had an usual shape, which looked less like a long graceful airship and more like a stubby little blimp. It was 150′ long, 50′ in diameter, and could only handle three aeronauts at a time.

Aeronauts weren’t too fond of the ZMC-2 and saddled it with a number of derisive nicknames: “The Tin Bubble.” “The Tin Balloon.” “The Flying Tomato Can.” Even so, they couldn’t deny that the airship did its job and did it remarkably well. A revolutionary control system that put elevators and rudders in all of the fins made it one of the most maneuverable airships ever built, and allowed it to function in strong winds that might have destroyed other lighter-than-air craft.

Even so, those advantages were outnumbered by the drawbacks. The small crew complement limited how it could be deployed. The all-aluminum construction meant the ship was super-expensive, which made it a hard sell during the Great Depression. The weight of all that aluminum also drastically limited the ship’s operation range.

No more metal-clad airships were ever commissioned. The ZMC-2 was never even officially christened. It was stationed in its own side hangar at Lakehurst, where it was used as a training ship for airmen and occasionally wheeled out to assist in search-and-rescue operations off the Jersey shore.

ZRS-4 “USS Akron” (1931-1933)

The ZMC-2 may have been a failure, but the Navy remained committed to the rigid airship program. If anything, it was even more into airships than it had been before. That’s because they had finally figured out another potential use for lighter-than-air craft: aircraft carriers.

Theoretically, an airship could be used to extend the operational range of more conventional airplanes by serving as a mobile launchpad. It wasn’t a new idea. The Germans and British had experimented with the concept in the waning months of World War I, but found there were two obstacles that needed to be overcome. After disgorging its planes an airship would be not only completely defenseless but in a vulnerable forward position. The planes, meanwhile, would have to find somewhere else to land, because while they could launch from a dirigible there was no way they could land on one.

Or maybe they could. In 1921 the Sperry Aircraft Company proposed an ingenious solution to that problem: the “sky hook.” It was essentially a bar suspended inside a gondola that planes could hook on to, like a trapeze. The sky hook could then be lowered to launch a plane, and raised to land it. The Army extensively tested the sky hook in 1924 and 1925, and found that while attaching to the sky hook in mid-air was tricky, it could be done. The concept was viable.

For rigid airships, at least, which they were not allowed to have.

The project was transferred over to the Navy, which conducted its own tests of the sky hook on board the Los Angeles in 1929. Shortly afterwards they began drafting plans for a dedicated airborne aircraft carrier: the ZRS-4. No, I don’t know where the “S” came from or what it means.

This time, the ship was built by American experts: the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company of Akron, Ohio. Goodyear had been building blimps since the turn of the century, and was interested in expanding into rigid airships. A military contract was an excellent way to finance their move into that space. Goodyear somehow completed the project in time and on budget, in spite of attempted sabotage by anarchists. In September 1931 the ZRS-4 was officially christened the USS Akron. On her maiden voyage, she was symbolically commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Rosendahl.

If the Shenandoah and the Los Angeles had been monsters, the Akron was a titan. She was 786′ long, 132′ in diameter, and carried 6,500,000 cubic feet of gas providing 91 tons of disposable lift. Eight 560 horsepower engines could propel her at 85 mph. She had three reinforcing keels, which would theoretically prevent her from breaking apart mid-air. Her gas bags were made not out of goldbeater’s skin, but Goodyear’s patented rubberized cotton which had the advantage of being resistant to lightning strikes. She carried a payload of three “parasite fighters.” (She was supposed to carry five, but the design of the superstructure meant that you couldn’t get five planes into the hangar without damaging some of them.)

The Akron‘s fighters were the Curtiss F-9C Sparrowhawk, one of the smallest and lightest planes to ever see military service, and purportedly a real pain in the tuchus to fly. Anything heavier would put too much stress on the sky hook and drag down the Akron. The teeny-tiny planes were not much good for anything other than, you guessed it, aerial reconnaissance. At least they also vastly increased the operational range of that reconnaissance. The Akron herself was capable of scouting a path 80 miles wide, but the Sparrowhawks doubled that to 160 miles. In a single day the airship and her fighters could sweep over 120,000 square miles of ocean, which was nothing to sneeze at.

Once the Akron was operational, the Navy had little use for the Los Angeles and she was formally decommissioned in 1932. Her gas bags were emptied, the helium was transferred over to the Akron, and she was moved into long-term storage at Lakehurst. It was in some sense foolish — the Los Angeles was still in good shape and probably had at least four to five years of operational life left, but she was no longer the new hotness so the Navy kicked her to the curb. (Ain’t that always the way?)

Unfortunately for the Navy, the new hotness was also a bit of a hot mess. The Akron kept getting into easily avoidable accidents. Fins were smashed during basic maneuvers, gas bags were accidentally punctured, crewmen kept falling to the deaths from the rigging. Usually with a newsreel crew right there to cover the whole debacle.

The Akron also performed no better in war games than the Los Angeles had. Conventional naval aircraft carriers outperformed the Akron on almost every conceivable metric. It was clear that the days of the rigid airship program were numbered — well, clear to everyone outside the program.

On April 3rd, 1933, the Akron was making a routine patrol along the New Jersey coast, only this time they had a special guest — Admiral Moffett, the program’s director. At 8:45 PM, she spotted a thunderstorm about 30 miles south of Philadelphia and moving rapidly in her direction. The storm overtook her at about 10:00 PM near Barnegat Light. In spite of the rapidly changing weather, Commander Frank C. McCord stubbornly remained on his pre-planned flight path. It was a dumb move. Yes, he had no way to outrun the storm, but with a little work he could have found the right place to weather it. It’s possible he was trying to impress Admiral Moffett by seeming unflappable in the face of danger.

The Akron was buffeted by fierce winds that blew her up and down. Mostly down, to the point where her belly was almost scraping the water. The crew tried to compensate by dumping ballast and opening the throttle to full. She leveled off at 700 or 800 feet — or so they thought. The altimeter worked off of barometric pressure, and the storm had screwed it to all hell. They dropped more ballast and the airship rose to 1600 feet. Maybe. At 12:15 AM, another squall hit and the Akron began dropping rapidly. Elevators were pushed as far forward as they could go, and the air ship yawed up at 25 degrees. That briefly arrested her descent, but then a powerful downdraft struck.

The Akron‘s tail made contact with the water. The stress caused the airframe to snap in two and both halves fell into the freezing waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

A nearby tanker, the Phoebus, saw lights on the horizon which it mistook for flares. It arrived at the scene of the crash and pulled four unconscious aeronauts out of the drink, one of whom died shortly after being rescued. The sailors might have been able to rescue more, but had no way of knowing there were more men out there to rescue.

Everyone else, including Commander McCord and Admiral Moffett, perished, mostly due to hypothermia. It turns out that for all the Akron‘s safety improvements it did not carry life jackets, and only had a single life raft.

ZRS-5 “USS Macon” (1933-1935)

The loss of 72 men at sea was the final straw. Public opinion was now firmly against the program and it’s hard to argue with that stance. After all, if an airship could be taken out by the weather what chance did it stand against an enemy military? The Brooklyn Daily Eagle was unusually succinct: “Build no more coffins of the air.”

The Navy had been planning to build a dozen airship carriers, and was forced to put those plans on hold. The stop order came too late for the ZRS-5. She had been completed and christened the “USS Macon” three weeks before — by Admiral Moffett’s wife, no less.

The admirals thought that maybe a change of scenery would improve the airship program’s long-term odds. They moved the Macon from Lakehurst to an airbase on the west coast — the newly renamed Moffett Field in Santa Clara county, California. They also made changes to the ship’s design, allowing it to finally carry a full complement of five Sparrowhawks, and further modifying the Sparrowhawks so they could carry larger fuel tanks and extend the ship’s operational radius even further.

It didn’t help. Though the Macon could quickly comb vast swaths of the Pacific for enemy ships, she continued to perform poorly in exercises with the Pacific fleet and was repeatedly shot down in mock combat. Admiral David F. Sellers was blunt: the Macon had “failed to demonstrate its usefulness” and “further expenditure of public funds for this type of vessel is not justified.”

On February 12th, 1935 the Macon was off of the California coast near Point Sur when it was battered by high winds. Unfortunately the airship was not operating at 100%. The girders supporting her rear elevators had buckled during a flight the previous year, and the damage had only been addressed with temporary repairs. The Navy was given a grim reminder of the importance of proper maintenance when the high winds ripped those elevators clear off the airframe at 5:18 PM.

Jagged metal shards slashed through nearby gas bags and the stern dropped precipitously. The crew dropped ballast to try and stay aloft, but that caused the Macon to rise above its operational ceiling. Automatic systems started venting the gas bags, and soon it was impossible to keep the ship afloat.

Fortunately, though, the Macon was skippered by Lieutenant Commander Herbert V. Wiley, one of the three survivors of the Akron‘s crash. He knew exactly what to do. He conducted an orderly evacuation as the airship slowly drifted down towards the ocean. There were plenty of life vests and life rafts on board, and in the end only two men lost their lives. Radio man E.E. Dailey had fallen in the first few instants and landed on his back in the ocean, dying on impact. Filipino mess boy Edward Quiday hesitated to slide down an escape rope because he could not swim and was standing next to a gas cell when it exploded. The 81 other crewmen paddled water until they could be rescued by the USS Pennsylvania.

Aftermath

Fortunately for the Navy, their embarrassment at losing a fourth airship was soon driven off the front pages by the conviction of Bruno Hauptmann, alleged kidnapper of the Lindbergh baby. Even so, the loss of the Macon was effectively the end of the rigid airship program.

Don’t get me wrong, the Navy still had grand designs. At the time they were drafting plans for the ZRCV, an absolute colossus of an airship. It would have been 897′ long, 148′ in diameter, and carry 9,550,000 cubic feet of gas along with either a dozen fighters or nine dive bombers. The problem was that Congress was never going to allocate another dime for airship construction, and rightfully so. Active work on the ZRCV plans ceased after the Hindenberg disaster in 1937, and the project was officially terminated in 1940. Plans for smaller rigid airships were also abandoned at the same time.

The Navy briefly considered re-floating the Los Angeles, but just didn’t have the budget for it. That left them with one final airship: the poor old ZMC-2. The Flying Tomato Can was still chugging along, helping out with search and rescue operations off the Jersey shore. It was the only one of the Navy’s six airships with a completely clean service record. (Not for lack of trying, mind you! On several occasions the good people of New Jersey had taken pot shots at the ZMC-2 with their hunting rifles, and a few had even hit.) In the opening months of 1941, the ZMC-2 finally reached the end of its operational lifespan and was quietly retired.

That was the end of the short, sweet history of rigid airships in the military.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

The obvious connection here is to last week’s episode, “The Sea King” which was about the CSS Shenandoah. Interestingly, despite the shared name there seems to be no direct connection between the two vessels — the airship was definitely not named after the privateer. Which is good, because if that was the case we’d probably have to cancel it.

The loss of the USS Akron was hardly the worst thing to happen in New Jersey. Take your pick: we’ve got insurance fraud (Series 4’s “Pleadings from Asbury Park”), the Jersey Devil (Series 6’s “What-Is-It?”), shark attacks (Series 8’s “Scarlet Billows”), and even eugenics (Series 8’s “Common Clay”).

Sources

- Flaherty, Thomas H. Jr. (ed). The Epic of Flight: The Giant Airships. Chicago: Time-Life Books, 1980.

- Graham, Margaret B.W. “R&D and Competition in England and the United States: The Case of the Aluminum Dirigible.” Business History Review, Volume 62, Number 2 (Summer 1988).

- Gray, Andrew. “Stand by for a Crash: The Demise of the Naval Dirigible.” Air Power History, Volume 39, Number 3 (Fall 1992).

- Nauton, Duke. “Flying — Simple and Unsophisticated.” Aerospace Historian, Volume 22, Number 4 (Winter 1975).

- O’Neil, William D. “Land-Based Aircraft Options for Naval Missions.” SAE Transactions, Volume 86, Section 4 (1977).

- Robinson, Douglas H. “The Zeppelin Bomber: High Policy Guided by Wishful Thinking.” The Air Power Historian, Volume 8, Number 3 (July 1961).

- Rosendahl, C.E. “Mooring Masts and Landing Trucks for Airships.” SAE Transactions, Volume 4 (1929).

- Rosendahl, C.E. Up Ship! New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1932.

- Ryan, Donald E. Jr. “Filling the Gap: The Airship’s Potential for Intertheater and Intratheater Airlift.” Air University Press, 1992.

- Smith, Richard K. “The ZRCV: Fascinating Might-Have-Been of Aeronautics.” Aerospace Historian, Volume 12, Number 4 (October 1965).

- “Lighter-Than-Air Follies.” The New Atlantis, Number 28 (Summer 2010).

- “Big airship to attempt flight overseas in spring.” Long Beach Telegram, 11 Jan 1921.

- “Death blows to Navy aviation seen in House’s economy.” Baltimore Sun, 16 Feb 1921.

- “World’s largest airship to cross Atlantic in May.” Chicago Tribune, 20 Feb 1921.

- Bradford, A.L. “US dirigible to cross Atlantic.” Charlotte News, 10 Apr 1921.

- “Cross-sea flight of R-38, or ZR-2, to US delayed.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 Apr 1921.

- “Navy getting ready to receive giant ZR-2, biggest rigid airship.” Washington Times, 15 May 1921.

- “Super-airship ready for ocean flight.” New York Herald, 26 Jun 1921.

- M’Gregor, Donald. “What the war toy ZR-2 means in money.” New York Herald, 14 Aug 1921.

- “Big dirigible is off on her maiden flight.” Dayton Herald, 23 Aug 1921.

- “ZR-2 falls in flames at Hull, carrying 44 to deat; 6 officers, 11 men of American crew among victims; Hoboken fire burns two piers, damages Leviathan.” New York Herald, 25 Aug 1921.

- “Divers fail to find 41 bodies entombed in wreck of ZR-2.” New York Herald, 26 Aug 1921.

- “ZR-2 wreck forces air policity decision.” New York Herald, 26 Aug 1921.

- “British and US airmen admit they knew ZR-2 was defective.” New York Daily News, 28 Aug 1921.

- “ZR-2 disaster will not stop American plans.” Chicago Tribune, 25 Sep 1921.

- “Recent tragedy causes little change in plans of ZR-1 now being built for navy.” Billings Gazette, 9 Oct 1921.

- “Charred skeleton of twisted metal marks the spot where 35 Americans died in crash of big Italian dirigible.” Albany-Decatur Daily, 22 Feb 1922.

- “Gas bag of big Navy Zeppelin to be made of gold beaters’ skins.” Baltimore Sun, 12 Jul 1922.

- “Possible for St. Louis to see the ZR-1 next year.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 24 Aug 1922.

- “Design of big Navy airship ZR-1 is now approved by experts.” Newport News Daily Press, 10 Dec 1922.

- Tinker, Clifford A. “To the top of the world in Navy’s huge rigid airship.” Boston Globe, 1 Jul 1923.

- Garret, Oliver H.P. “Cruise of giant ZR-1 over New York described by observer in airplane.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 12 Sep 1923.

- “Our new German-made behemoth of the air.” Hamilton Evening Journal, 15 Sep 1923.

- “ZR-3 sails to US early this fall.” Washington Evening Star, 20 Sep 1923.

- “ZR-1 defeats stiff winds which delay flight to St. Louis.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 2 Oct 1923.

- “Dirigible to be repaired in a month.” Franklin News-Herald, 18 Jan 1924.

- “Shenandoah to be tested out Thursday.” Brooklyn Citizen, 12 May 1924.

- “ZR-1 undergoes big test today.” New York Daily News, 26 May 1924.

- “President wires warm greeting.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 16 Oct 1924.

- “Captain Steele of the dirigible Los Angeles tells of his experiences as an airman.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 25 Jan 1925.

- “USS Shenandoah ready to go to Amundsen’s rescue.” Port Chester Daily Item, 19 Jun 1925.

- “15 perish as Shenandoah breaks in 3 parts during electric storm over Ohio; many hurt.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 3 Sep 1925.

- “Shenandoah wreck looted.” Boston Globe, 4 Sep 1925.

- “Disaster perils Navy air policy.” Washington Evening Star, 4 Sep 1925.

- “Fatal crash of dirigible described by survivors.” San Francisco Examiner, 5 Sep 1925.

- “Publicity motive in voyage denied.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 Sep 1925.

- Beamish, Richard J. “Expert lays crash to willful negligence.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 Sep 1925.

- “Salvaging wreck of Shenandoah.” Baltimore Sun, 7 Sep 1925.

- Tipton, William D. “Think Shenandoah may have paid for Lakehurst escape.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 8 Sep 1925.

- “Wilbur disclaims any blame for Navy airship disasters.” Washington Evening Star, 10 Sep 1925.

- “Gotham sees Los Angeles.” Los Angeles Times, 14 May 1926.

- “Air navigator sees future for skyships.” Los Angeles Evening Express, 12 Oct 1926.

- Wilkie, David J. “All-metal dirigible sets new style.” Moline Dispatch, 28 Aug 1929.

- Righter, Harold E. “Little gold rivet starts work on biggest airship.” Brooklyn Times-Union, 7 Nov 1929.

- “Queen of the sky roads.” Los Angeles Times, 5 Jan 1930.

- “Metal airship built in U.S. passes test.” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 17 Mar 1930.

- “ZRS-5 contract not canceled.” Washington Evening Star, 6 Aug 1930.

- Taylor, Harld J. “Reasons for carrying out contract for second airship cited.” Akron Beacon Journal, 25 Sep 1930.

- “Airship called a weak weapon.” Detroit Free Press, 8 Mar 1931.

- Smith, Robert B. “World’s largest airship nearly ready.” Cincinnati Enquirer, 3 May 1931.

- “Red, working on dirigible, under arrest.” Green Bay Press-Gazette, 20 Mar 1931.

- “New U.S. dirigible faces rigid tests to assure safety.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 2 Aug 1931.

- Pyle, E.T. “Interesting job of the belly bumpers.” Evansville Press, 23 Aug 1931.

- Taylor, Harold J. “Slight changes are expected in ZRS-5’s design.” Akron Beacon Journal, 11 Nov 1931.

- “Going and coming.” Evansville Press, 25 Dec 1931.

- “Los Angeles may be sold, money used for ZRS-5.” Akron Beacon Journal, 29 Jan 1932.

- Taylor, Harold J. “ZRS-5 will be ‘overweight’ but safety factors more important.” Akron Beacon Journal, 10 Feb 1932.

- “Helium’s loss delays Akron.” Detroit Free Press, 14 May 1932.

- “Exit the Los Angeles.” Miami News, 5 Jul 1932.

- “Storm delays airship Akron.” Dayton Daily News, 26 Jan 1933.

- “Akron breaks to pieces in storm at sea; 73 dead.” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, 4 Apr 1933.

- “Give new version of Akron tragedy.” Visalia Times-Delta, 11 Apr 1933.

- “‘Macon‘ flight recalls initial trip by ‘Akron.'” Akron Beacon Journal, 21 Apr 1933.

- “Macon crashes in ocean; warships hunt survivors.” Fresno Bee, 12 Feb 1935.

- “Macon sinks, two dead.” San Francisco Examiner, 13 Feb 1935.

- Hyman, Alvin D. “Macon quiz opens; survivors return; Wiley tells story.” San Francisco Examiner, 14 Feb 1935.

- “Wiley hints Macon crashed because of faulty design.” San Francisco Examiner, 15 Feb 1935.

- “Defect in Macon caused wreck!” San Francisco Examiner, 16 Feb 1935.

- “Navy lieutenant does ‘about face,’ now tells board Macon was safe.” San Francisco Examiner, 17 Feb 1935.

- “‘Weather didn’t sink the Macon.'” San Francisco Examiner, 19 Feb 1935.

- “Macon inquiry ends, defect in design blamed.” San Francisco Examiner, 22 Feb 1935.

- “Sniper fires on ZMC-2 as it aids in search for body.” Asbury Park Press, 1 Aug 1935.

- “Tho ships fall, Lakehurst’s spirit moves on.” Asbury Park Press, 11 Jun 1936.

- “2 firms after zepp contract.” Akron Beacon Journal, 25 Jan 1939.

- “Time proves metal airship, but U.S. won’t be convinced.” Detroit Free Press, 6 Aug 1939.

- Talbert, Ansel E. “Dirigible Los Angeles is ordered dismantled.” Dayton Daily News, 8 Dec 1939.

- Francis, Devon. “Dirigibles seen returning to favor.” Miami Herald, 18 Feb 1940.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: