Rapscallions!

"Patience is Sour"

In the final year of the American Civil War the Confederacy turned to terrorism, sabotage, and subterfuge.

This isn’t to say there wasn’t espionage going on before then; wherever there’s a war there will be spies at work. For the first three years of the war, though, the Confederates were happy to restrict their operations to military targets.

In the last sixteen months, they turned those operations loose on civilian targets as well.

Why did it take the Confederates so long to adopt this strategy? In various Lost Cause apologia it is often suggested that this change was intended to force a diplomatic end to the war by demoralizing the civilian population. It is also suggested the Confederates had previously avoided this strategy because it was seen as “ungentlemanly” or “dishonorable.” Alas, they were ultimately forced to stoop to the Union’s level, especially after its embrace of total war.

You have to take these excuses with a grain of salt, because Confederates and Lost Cause historians are masters of self-justification. The Confederacy had always been willing to target innocent civilians, commercial activity, and other non-military targets. Of course when Southern gentlemen did it was all nice and proper, done politely, and only because those damned Yankees had forced their hand.

Let’s be blunt: the only reason the Confederates changed their strategy is because it became obvious they were losing and there was no way to change that outcome through conventional warfare. In desperation they turned to the cloak-and-dagger crowd as their last possible salvation.

From February 1864 through April 1865, Confederate agents based out of Canada waged a campaign of terror across Northern states far removed from the usual battle lines. Over the next three episodes we’ll be telling their stories.

So let’s get started.

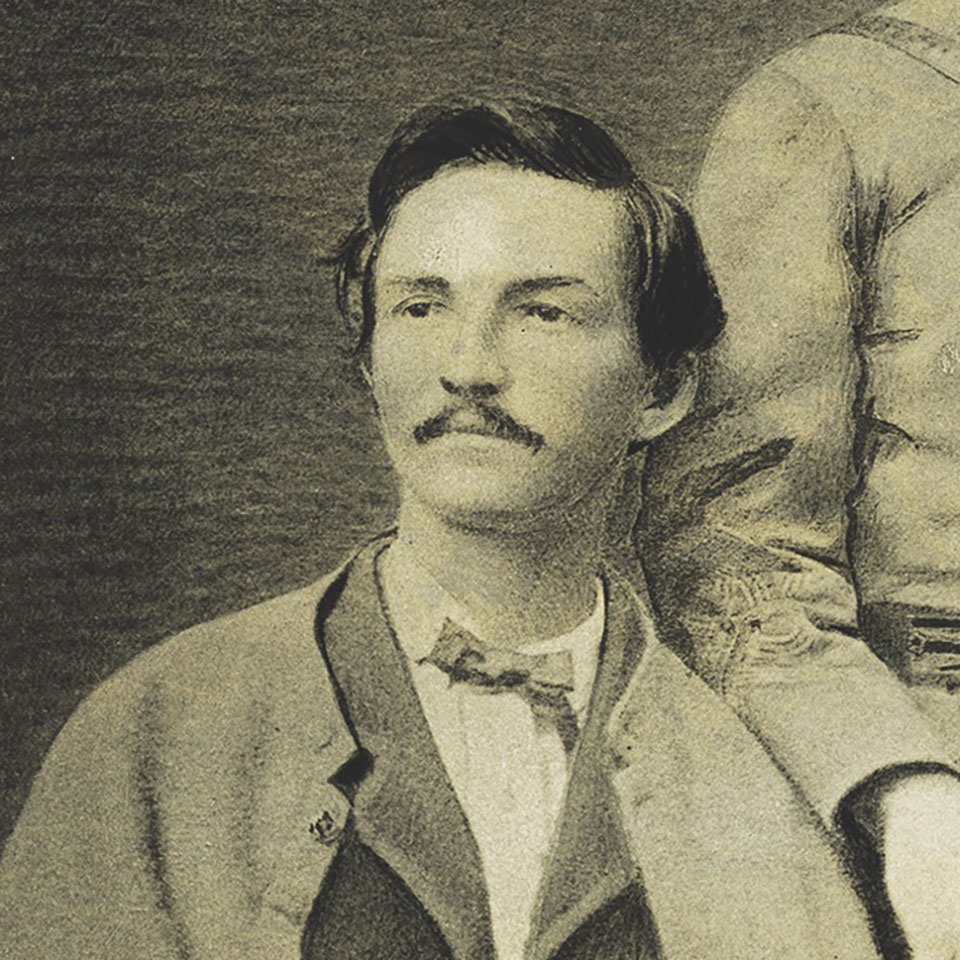

Thomas Henry Hines

Thomas Henry Hines was a 23-year-old faculty member of Masonic University in La Grange, Kentucky when the secession crisis broke out. Though Kentucky ultimately chose to remain in the Union, large numbers of Kentuckians sympathized with the Confederacy, including Hines. He defected and enlisted in General John Hunt Morgan’s Kentucky Cavalry, where he quickly rose to the rank of captain.

In the summer of 1863, General Morgan was given orders to take a small force behind enemy lines and make trouble. Officially, Morgan’s goal was to support the Vicksburg campaign by tying up potential reinforcements hundreds of miles from the front. Unofficially, Morgan’s goal was make his way east, join up with Robert E. Lee’s Army of the Potomac in Pennsylvania, and march on Washington, DC.

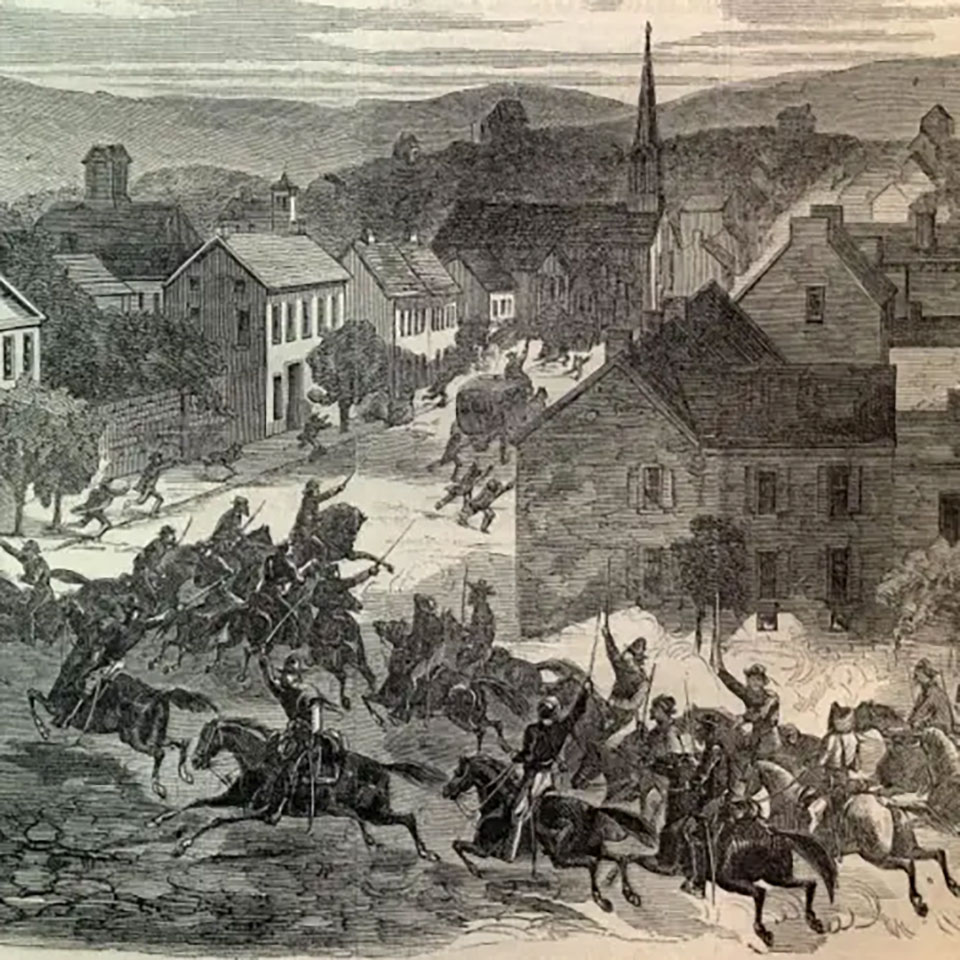

Morgan’s Raiders set out from Burkesville, Kentucky on on July 2, 1863 and crossed over into Indiana a week later. The Union Army was caught by surprise, and locals scrambled to mobilize their militias. For two weeks Morgan rampaged across the countryside virtually unopposed.

During the raid Captain Hines worked as a scout, moving ahead of the army, delivering messages, spying on enemy troop movements, and liaising with local Copperheads.

So I guess I have to interrupt the story and explain Copperheads.

Copperheads

The simplified version of the Civil War taught in most schools depicts the North and South as culturally and politically homogenous units, but that’s not true. Each sides had internal factions based on regional, philosophical, and political differences.

In general, the North was broadly pro-Republican, pro-Union, and anti-slavery. However, outside of their strongholds the Republicans held only a slim majority, and their electoral support wavered a lot based on how well the war was going at any given moment.

Opposition to the Republicans was strongest in the Northwest; not the Pacific Northwest, mind you, but the old Northwest Territory (the area north of the Ohio and east of the Mississippi). Specifically, we’re talking about the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Wisconsin, and Minnesota.

Fortunately for the Republicans, that opposition was not united, but a loose coalition of small interest groups with widely divergent goals. There were:

- conservative reactionaries opposed to any sort of change;

- civil libertarians who actually bought into the states’ rights justification for the war and who opposed Federal overreach in other areas;

- pacifists and anti-war activists;

- outright Confederate sympathizers and pro-slavery racists;

- abolitionists who feared radical Republicans would destroy the cultural dominance of whites;

- abolitionists who did not give a fig about preserving the Union;

- regionalists who distrusted Northeastern elites;

- and rural farmers with strong economic and social ties to the South.

The unofficial spokesman for these groups as a whole was Ohio Congressman Clement Laird Vallandigham, the leader of the so-called “Peace Democrats.“

Vallandigham was a powerful orator who could hold a crowd in the palm of his hand. In his speeches he accused Republicans of being tyrannical monarchists in thrall to “King Lincoln” and railed against New England profiteers who he believed were prolonging the war for financial gain.

Mind you, Vallandigham had no idea how to actually end the war. His only suggestion was childishly simplistic: “Withdraw your armies, call back your soldiers, and you will have peace.” As if the mere presence of soldiers was the only reason the war existed in the first place.

These days we call these factions “Copperheads,” an insult the Republicans used to imply that they were snakes-in-the-grass. At the time, though, the term was more specific. You could be against the war without being a Copperhead, and many were.

What made you a Copperhead was being a member of an explicitly anti-Republican secret society. Of which there was really only one.

So I guess I have to interrupt this interruption to explain the Secret Order of American Knights.

The Secret Order of American Knights

Americans have always loved secret societies. In olden times when power had yet to consolidate in government hands, they were often the fastest and easiest way to organize your neighbors and get things done. Secret Societies combined all the business of politics with all the fun of frat parties and beer league softball. What’s not to like? Before the mid-Twentieth Century almost everyone in America was a Son of Liberty, a Freemason, an anti-Mason, a Tammany Hall man, a Know-Nothing, an Elk, a Moose, an Odd Fellow, a Son of the Desert, or something similar.

So it should be no surprise that in the Antebellum period there were pro-slavery secret societies.

The largest of these was the Knights of the Golden Circle, which worked to create a slaveholding empire, a “Golden Circle” centered on Havana with a thousand mile radius. They worked to make that dream a reality by supporting pro-slavery politicians, sponsoring the African slave trade (even when it was illegal), and financing filibustering expeditions into Central America.

The Knights had worked to arm and organize the Confederacy in the early days of the secession crisis. Then it withered away, a victim of its own success. Like Alexander, it had no worlds left to conquer.

There had been Northern chapters of the Knights of the Golden Circle, but they never had very many members; the organization was too obnoxiously Southern, racist, and pro-slavery to appeal to many people above the Mason-Dixon Line. When war broke out those few chapters were quickly exposed and destroyed by Republican crusaders like Governor Oliver Hazard Perry Throck Morton of Indiana.

A friendly secret society would be a useful ally that could advocate for Confederate interests in the North, so Confederate sympathizers made several attempts to re-create the Knights of the Golden Circle. Eventually there were more than a dozen or so copycat organizations, including:

- the Knights of the Golden Square;

- the Knights of the Columbian Star;

- the Order of the Star;

- the Star Organization;

- the American Association;

- the Southern League;

- the Corps de Belgique;

- the Democratic Invincible Club;

- the Democratic Reading Room;

- the McClellan Minute Guard;

- the Circle of Honor;

- the Mutual Protection Society;

- the Order of the Mighty Host;

- and the Paw Paws.

There is some debate as to whether all of these societies were actual successors to the Knights of the Golden Circle. At first glance, they do seem to be shallow copies with the serial numbers filed off: their internal hierarchy was identical, their oaths and rituals are very similar, even some their symbolism like the “Columbian Star” come right from Golden Circle literature.

At the same time those symbols are often just generic patriotic symbols, and many of the organizational similarities are more likely a result of secret societies copying the grandaddy of them all, the Freemasons.

The most successful of these copycats was the Secret Order of American Knights, which had been founded in 1856 by Phineas C. Wright. Wright was a former member of the Corps de Belgique, the rabble-rousing editor of the New York Evening News, and an infamous Copperhead. In 1863 he somehow persuaded many of the other Golden Circle pretenders to join forces under his banner.

The consolidated Order of American Knights boasted that it had half a million members in almost every Union and Confederate state, and several Central American countries to boot. (More sober analyses seem to indicate it was less than half that size, and geographically constrained to the Midwest.)

Its membership included many well-to-do businessmen and prominent Democratic politicians. It is not clear how many of them were actually anti-Republican or pro-Confederate; back in those days it was not uncommon for ambitious men to join every secret society they could as a way of getting ahead, and tended to not ask questions about their long-term goals.

Somehow this massive consolidation was done in secret. When the average joe went down to the meeting hall the sign over the door still said “The Order of the Mighty Host,” the same people were still wearing the same old robes, and the oaths and rituals they chanted were unchanged. The leaders, though, knew they were secretly the Order of American Knights.

And they were just waiting for a moment when they could mobilize this massive Copperhead organization to make a difference during the war.

Back to Morgan’s Raid

Okay, that’s enough context for now. So let’s turn back the clock six minutes and talk about Morgan’s Raid of July 1863.

During the raid Captain Hines worked as a scout, moving ahead of the army, delivering messages, spying on enemy troop movements, and liaising with local Copperheads. He was aided in this endeavor by his silver tongue and extremely good looks, which had farmer’s daughters up and down the Ohio Valley falling at his feet. (There are a lot of farmer’s daughters being seduced in Hines’ memoirs, to the point where one suspects he’s either compensating for something or trying to protect collaborators and traitors by blaming everything on nameless jezebels.)

Hines soon discovered that the local Copperheads were not capable of or inclined to provide any sort of meaningful assistance as there was no benefit to them to do so. The problem was that Morgan and his men were raiding, moving quickly and seemingly randomly, so they could not provide advance notice of their movements without tipping their hand to the Union army chasing them. By the time Copperhead leaders learned that Morgan’s men were heading their way, they had no time gather supplies for the raiders or call out the troops to support them. And since Morgan wasn’t planning on sticking around, providing aid and comfort to the raiders risked exposing the Copperheads as traitors and subjecting them to reprisals when the Confederates moved on.

Meanwhile, rank-and-file Copperheads had to deal with the reality that Confederate soldiers were looting and pillaging the countryside. They had been taught secret signs and signals that would keep their own property safe, but it turned out those signs and signals were hoaxes that did not work. If anything, they seemed to make matters worse. Morgan’s Raiders seemed to take special relish in targeting Copperheads, telling them they should be happy to give everything they had for the cause.

Without local support, Morgan quickly stretched his supply lines past their breaking point. On July 19 he decided to retreat back to Kentucky. He soon discovered that the Ohio River was flooded, every ford across it was now heavily defended, and that the Union army was closing in from the west. For over a week he stumbled east looking for an escape route, constantly under fire and losing troops the entire way, before surrendering at the outskirts of East Liverpool, Ohio on July 26, 1863.

Morgan, Hines and the other captured officers were briefly sent to a prisoner-of-war camp on Johnson’s Island, near Sandusky. They were hardly model prisoners. In fact, to protest the lack of provisions there they trapped, killed, and cooked the commandant’s dog, leaving behind the following bit of, uh, doggerel as a taunt.

For want of bread

Your dog is dead

For want of meat

Your dog is eat

Shortly afterward the raiders were transferred to THE Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus, with the implication being that they were not prisoners-of-war but common criminals.

Hines planned a dramatic escape, partly inspired by the new English translation of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables but mostly inspired by the lax security at the state pen. For three weeks the prisoners dug a tunnel to freedom with only a broken pocket knife and some butter knives stolen from the canteen. Hines covered for them by sitting on a cot that hid their tunnel from view and reading Gibbons’ Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire out loud to bore away any guards who drew near.

They slipped out of the prison on November 27, and this time they left behind a slightly more tasteful note.

La Patience est amère, mais son fruit est doux.

(“Patience is sour, but its fruit is sweet.”)

Morgan and Hines made their way south, hopping trains when they could, hoofing it when they couldn’t, and hiding out with friendly Copperheads wherever they went. At one point Hines even allowed himself to be captured to allow Morgan to escape, used his silver tongue to talk his way out of a lynching, then escaped again and reunited with Morgan to finish the journey.

Well, at least that’s the romantic version of the story Hines put in his memoirs. The more likely version of events is that Morgan and Hines bribed their jailers, walked out the front door of the prison unmolested, and then beat feet for Kentucky.

The Great Northwestern Conspiracy

Thomas Henry Hines was now free and eager to get back into action.

In January 1864 he traveled to Richmond to propose a daring new scheme: using secret agents to free Confederate soldiers from prisoner-of-war camps. (Okay, it wasn’t entirely new. A similar plan had been proposed in 1862 by Captain Charles Longuemare, and rejected. But I digress.)

Having just escaped from a Northern prisoner-of-war camp, Hines knew that they were poorly built, extremely overcrowded, and horribly insecure.

He believed a massive prison break would succeed if it had outside assistance, provided by a handful of secret agents operating out of Canada. Those agents could slip back-and-forth across the porous international border with impunity, and Canadian authorities would not interfere with their operations as long as they kept their overtly hostile acts on the American side of the border. Additional support would be provided by local Copperheads.

You might be surprised that Hines was willing to take a chance on Copperheads given that they had just failed him, but he believed the Copperheads had been set up for failure. This time they would be part of the plan from the beginning, giving their secret societies time to transform into a paramilitary fighting force that could seize state arsenals, rearm the prisoners-of-war, and stall Union forces.

The end result would be a massive army, tens of thousands strong, hundreds of miles behind enemy lines. The Union would either have to withdraw troops from its offensive campaigns to subdue them, or let them run wild in the heartland. During the resulting chaos the Copperheads could overthrow their state governments and withdraw their support for the war effort.

It was a good plan, certainly worth exploring. Alas, the Confederate leadership was still worried about optics. Subterfuge seemed unbecoming of Southern gentlemen. Public opinion in the North would justifiably regard such work as treachery, and public opinion in the South would almost certainly regard it as dishonorable and Yankee-ish.

They decided to pass.

So what changed their mind?

In February 1864 the Union launched their own secret raid to free Union soldiers being held in Richmond prisoner-of-war camps. It was a spectacular failure and its leader, Ulric Dahlgren, was killed. Plans recovered from his body seemed to indicate his secondary objectives included razing Richmond to the ground and assassinating Jefferson Davis.

There is some debate as to whether those objectives were part of Dahlgren’s official orders, his own personal objectives, or Confederate disinformation. The important thing is that their discovery rattled the Confederates and rattled them good. If the North was willing to stoop so low to win the war, then the South would have to stoop lower.

Jefferson Davis immediately greenlit a plan to create a network of Confederate operatives in Canada to engage in spycraft, subterfuge, sabotage, and other dirty tricks to hamper the Northern war effort. He tapped three men to lead it:

Jacob Thompson, formerly James Buchanan’s Secretary of the Interior, was the money man, with access to over a million dollars in Confederate gold that had been laundered through Montreal banks.

Clement Claiborne Clay, former Senator from Alabama, was the charming diplomatic face of the operation who would reassure the Canadian authorities while making contacts with Confederate expatriates already in the country.

Serious-minded James P. Holcombe was there to monitor the other two and keep things grounded and moving.

At least, that was the plan. Clay had a falling out with the other two over goals and methods, then fell ill and left to focus on his recovery. Holcombe proved to be a junior partner at best, unable or unwilling to press his own opinions. Thompson turned out to be the easiest mark there ever was, wasting hundreds of thousands of dollars on hare-brained schemes that went nowhere.

(On one occasion he was approached a rando who claimed he was there to buy guns for Judah P. Benjamin but said he had misplaced his official orders. Thompson gave him $3,000 and then very predictably never saw him, the money, or the guns ever again.)

That’s all in the future, though. Right now the three commissioners’ top priority was Thomas Henry Hines’ plan or, as it would come to be known, “The Great Northwestern Conspiracy.”

Hines arrived in Toronto in April 1864.

At the time the city was a wretched hive of scum and villainy, packed full of Yankee deserters, escaped Confederate prisoners-of-war, war profiteers, smugglers, assassins, ne’er do wells of any description, and Argonauts fans.

The Southerners, at least, tended to congregate in the lobby of the Queen’s Hotel on Front Street. So that’s where Hines went.

He had his pick of potential co-conspirators, but wound up assembling a team of men he knew from Morgan’s Raiders, including Lts. Bennett H. Young and John W. Headley; Capts. John Breckinridge Castleman and Robert Cobb Kennedy; and Cols. George B. Eastin, Robert Martin, and George St. Leger Ommaney Grenfell.

(A Brief Digression about George St. Leger Ommaney Grenfell)

Let’s take a quick moment to talk about Grenfell, because he’s a fascinating character who’s probably not worth a full episode.

George St. Leger Ommaney Grenfell was a 62-year-old British aristocrat who ran away from home to become a soldier-of-fortune against his parents’ wishes. He fought for the French against the Arabs; switched sides to become the personal bodyguard of Algerian rebel leader Abdelkader; conducted a “one-man war” against pirates in Morocco; fought for the Turks in the Crimea; helped put down the Sepoy Rebellion in India; and rode with Garibaldi’s South American Legion. When the Civil War broke out, he was struck by the nobility of the Confederate cause and the Southern way of life and enlisted.

That was the story as Grenfell told it, and as it was uncritically repeated by Lost Cause historians for a hundred years. Eventually historians who weren’t wearing rose-tinted glasses took a closer look and realized it couldn’t possibly be true unless Grenfell had a teleporter or a time machine or possibly both.

It turns out Grenfell was actually a 56-year-old British nepo baby who managed the French branch of his father’s company; briefly served in the National Guard during the July Revolution of 1830; fled the country when he was caught committing financial fraud; became a smuggler in Algeria; briefly served as a liaison between the British and the Turks in the Crimea (though he never saw combat); and then knocked around South America as a filibusterer and ne’er do well before heading north to join the Confederate army.

Grenfell eventually wound up attached to Morgan’s Raiders, where he made a name for himself by wearing a bright red cap that made him an easy target, compulsively bathing in every stream he came across, and never shutting up about how awesome he was.

He was captured with the others at the end of the raid and immediately created a enormous diplomatic problem for the Union. While he was an enemy combatant, he was also a British citizen. Throwing him into an overcrowded, unsanitary prisoner-of-war camp might persuade Her Majesty to abandon her neutrality. We couldn’t have that.

Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton offered Grenfell a deal: give up some military intelligence, swear that you won’t take up arms against the United States, and you can go free. Grenfell agreed. His so-called “intelligence” was fake, but by the time Stanton realized that Grenfell was in Canada and reunited with his old friends.

End of digression.

Clement Laird Vallandigham

Now that they had the band back together, Thomas Henry Hines and Jacob Thompson traveled to Windsor to meet with Clement Laird Vallandigham.

Begin new digression.

Clement Laird Vallandigham was an undistinguished and unsuccessful Democratic politician, until he lost the 1856 Congressional race in Ohio’s Third District by a mere nineteen votes. For two years Vallandigham ranted and raved that Republicans had stolen the election from him. He was so obnoxious and persistent that eventually the House of Representatives expelled his opponent and gave Vallandigham the seat… on the last day of the term, making it a symbolic victory at best.

Vallandigham was able to ride the outrage to victory in 1858 and quickly became one of the loudest pro-slavery voices in Congress. It turns out he was a huge racist who believed African-Americans were a “spurious and mongrel race” who did not deserve civil rights, and thought of slavery as a simple matter of property rights. And boy, did he love property rights.

During the secession crisis, Vallandigham attempted to play peacemaker by proposing a series of amendments that would restructure the country into four geographic confederacies with sweeping powers of nullification that would make legislation virtually impossible without an overwhelming super-majority in all four regions. As this would have the net effect of giving the South everything it wanted, no one else took it seriously at all.

Eventually Vallandigham became the unofficial leader of the Peace Democrats, making fiery speeches accusing New England elites of provoking the war for philosophical interests and prolonging it for personal gain. This particular brand of crazy did not play well in Ohio. Though anti-war Democrats did well in the 1862 midterm elections, Vallandigham lost his seat by a landslide.

Then he ran afoul of General Ambrose Burnside. Burnside had been recently placed in charge of the Department of the Ohio, and in an attempt to shut down what he saw as dissent and sedition issued General Order No. 38…

The habit of declaring sympathies for the enemy will not be allowed in the department. Persons committing such offenses will at once be arrested, with a view to being tried as [spies or traitors]… or sent beyond our lines into the lines of their friends.

The order was obviously illegal and unconstitutional, and Vallandigham saw an opportunity. On May 1, 1863 he gave a speech in Mount Vernon, Ohio where he spit on a copy of the order, thundered that “King Lincoln” had “plunged the country into cruel, bloody and unnecessary war,” and asked voters to “hurl the tyrant from his throne.”

He was trying to provoke Burnside, and boy howdy did he.

At 3:00 AM on May 5, sixty soldiers turned up at Vallandigham’s house to arrest him. As they knocked down the front door, Vallandigham barricaded himself in the bedroom and fired several shots out of the window into the darkness, chanting “Asa Asa Asa!” (No one knows why.) He was eventually dragged out of the house, plunked in front of a military commission, tried, found guilty, and sentenced to imprisonment for the remainder of the war.

Burnside had unintentionally proved Vallandigham’s point that the government was trampling American civil liberties. Democrats used the incident to score political points, and Republicans were put on the defensive. President Lincoln tried to salvage the situation by commuting Vallandigham’s sentence from imprisonment to exile. He was packed off to Shelbyville, Tennessee; walked over to enemy lines under a flag of truce; and unceremoniously abandoned there.

The Confederates made Vallandigham the toast of the town for a week or two, but quickly realized he was more worried about his own personal brand than he was about their cause. Eventually he made his way to Canada and established a base of operations in Windsor. From there he could send messages to his supporters in Ohio and whip them into a frenzy.

That frenzy eventually made him the Democratic candidate for Governor of Ohio in the 1863 election, though he still had to run his campaign from exile. He lost by more than 100,000 votes. Support for the Peace Democrats was largely contingent on the war, and unfortunately for Vallandigham it looked like the Union was winning. It did not help that a certain Confederate cavalry raid had gone right through southern Ohio, either. It turns out when there are boots on the ground and crops being burned voters are more concerned about practical matters than lofty principles.

From that description it might seem like Vallandigham was a spent force. So why would Hines and Thompson bother to visit him?

It turns out now he had the backing of an entire secret society.

The Sons of Liberty

Let’s get back to the Order of American Knights. Many of its leaders were prominent Democratic politicians, and with a presidential election looming they wanted to transform the Order from an anti-Republican one to a pro-Democratic one. They envisioned it as a version of the Republicans’ Union Leagues, which would work behind the scenes to support Democratic candidates. And maybe provide them with a Second Amendment solution if it looked like Republicans were stealing the election.

The American Knights were too fragmented and decentralized to fulfill that function. Not only were there too many redundant levels of organization, most members were still unaware that they were American Knights. So the leaders convened a national meeting in New York City on February 22, 1864 to do a bit of reorganization and rebranding.

After the meeting the American Knights changed their name to “The Order of the Sons of Liberty” and began claiming to be a revival of the Colonial-era secret society of the same name. (You may remember them as the ones who threw all that tea into Boston Harbor.) This time the name change did make its way the local lodges, confusing the rank-and-file to no end. Few of them were aware that they had been part of a larger national organization. Even fewer of them were aware that that organization now had a paramilitary wing that was actively equipping and training a militia.

Also at that meeting, the Sons of Liberty named Clement Laird Vallandigham their “Supreme Commander.”

There’s no indication that Vallandigham had previously been involved with the American Knights, but it’s not impossible; like many politicians he was a serial joiner of secret societies. What seems more likely is that the Sons of Liberty were using Vallandigham’s infamy to get publicity. (“Supreme Commander” seems to have been a largely ceremonial position in any case, and Vallandigham’s chief contributions seem to have been rewriting the organization’s oaths to be more dogmatic and slogan-heavy.)

The Northwest Confederacy

Hines and Thompson didn’t know any of that. What they knew was that was that a prominent anti-war politician was living in exile and had recently been named head of a large pro-Confederate secret society. So in early June, they went to meet with Vallandigham to see if they could work with the Sons of Liberty.

As usual, Vallandigham talked a big game. He crowed about his few accomplishments. He exaggerated his political strength. He boasted that he had 300,000 Sons of Liberty under his command, all of them ready to take up arms to defend their civil rights.

More than that! Remember that amendment Vallandigham had proposed, which would have split the country into four regional confederacies? He had a new iteration of that plan. The Sons of Liberty would seize control of the Northwestern states and create their own “Northwest Confederacy” responsive to their own interests. Maybe that meant independence, maybe that meant joining the South, or maybe that meant joining forces to crush the Northeast and reunite the United States.

Thompson was dazzled by Vallandigham’s patter. What an idea! An alliance between the South and Northwest would easily be able to crush the Northeast. Even if there was no alliance, the lost of the Northwest would cripple the Union. Even a failed revolution would spread division, doubt, and doom.

Hines was a little more skeptical. He thought maybe Vallandigham’s mouth was writing checks that his wallet couldn’t cash. But he kept those thoughts to himself.

Vallandigham would have been an ideal ally, save for one thing. He was willing to work with the Confederates, but not for them. He would not take their money, no matter how much they offered.

Then, on June 15, Vallandigham made a surprise appearance at a Democratic convention in Ohio. In one fell swoop he thumbed his nose at Lincoln’s exile, re-entered national politics, and cut himself off from the Sons of Liberty.

The day-to-day operations of the society devolved to the state-level Grand Commanders and Councils of Thirteen. Hines had met and worked with many of these men during Morgan’s Raid, men like James J. Barrett, the Sons of Liberty’s Adjutant-General; William A. Bowles and Harrison H. Dodd of Indiana; and Judge Joshua Fry Bullitt of Kentucky.

It turned out they had a lot fewer scruples about taking Confederate money than Vallandigham had.

Hines had everything he needed to get started: money, agents, and allies. All he needed now was a plan, and the one he drew up was a doozy.

It would start at Camp Douglas in Chicago. Its urban setting made it uniquely vulnerable, and security there was hardly tight — in fact, at one point prisoners were able wander out of camp and down the street to have lunch downtown. The Sons of Liberty would attack the camp from the outside while the prisoners rioted inside. In the chaos, Hines and his hand-picked agents would seize control. Simultaneously Capt. Castleman would strike at Rock Island on the other side of the state.

The two prison breaks would free some twenty thousand Confederate soldiers, who would be armed and equipped by the Sons of Liberty. They would rampage across the countryside, making their way south to join forces with raiders moving north. Meanwhile the Sons of Liberty would seize Federal arsenals, overthrow their state governments, declare independence, and free even more Confederate prisoners.

Hines scheduled the operation for July 1, but after some pushback rescheduled it for July 4. In the end he reluctantly conceded that everyone could use a few more days to prepare, and starting a revolution on Independence Day had a certain poetic irony to it.

That was still only a few weeks away, though, and there was so much to be done: there were militas to train, timetables to synchronize, palms to be greased, prisons to be cased. Thompson opened up his wallet and Hines spent freely. Records show he spent:

- $2,000 for railroad tickets, and another $2,000 to bribe railroad employees;

- $3,000 to rent horses for freed prisoners who were cavalry officers;

- $2,000 to lodge conspirators in hotels before the attack;

- $3,000 for couriers to coordinate everything;

- and $2,000 to “raise the Irish” (which seems to be code for buying cases of Monongahela rye and Old Rifle Whiskey).

That doesn’t include the small fortune they spent on armaments for the Sons of Liberty. Rifles and pistols were acquired in bulk from every merchant who had them for sale. They contacted Dr. Richard Jordan Gatling to see if they could acquire several of his eponymous guns. They bought hundreds of firebombs from R.C. Bocking, a chemist who claimed to have rediscovered the long-lost formula for Greek fire, which could not be extinguished by water.

Sons of Liberty across the Northwest were organized into small units and began training. As for the Confederates, Hines reached out to his old friend Capt. Adam “Stovepipe” Johnson and persuaded him to make a raid into Kentucky that would keep Federal troops occupied.

Everything seemed to be going smoothly.

That should have been the first warning sign.

The Best Laid Plans

The commandant of Camp Douglas, Col. Benjamin Sweet, began hearing rumors that there would be a massive prison break. At the same the he noticed his prisoners were sending more outgoing correspondence than ever, but leaving a lot of pages blank. He realized they were writing with invisible ink made from lemon juice, grabbed a candle, and uncovered the entire plot.

Sweet alerted the Department of War and asked for reinforcements, but there were none to be had. Instead he canceled leave and put the camp on high alert. When Independence Day came and went without a prison break, Sweet assumed his due diligence had saved the day.

He could not have been more wrong.

The Sons of Liberty had panicked as Independence Day approached. They went back to Hines and told him they needed more time to prepare. Many of their men had not been adequately trained for the task at hand. Worse than that, most of those men had not even been told what the task at hand was.

Hines was not happy, but agreed to give the Sons of Liberty two weeks to get their act together. Then someone pointed out that if he made it three weeks, the Democratic National Convention would be coming to Chicago on July 20. The influx of out-of-state delegates would help cover the movements of their own troops. Hines liked that. July 20 it was.

Then the Democrats delayed their convention to August 29.

The conspirators met in Chicago on July 20 to discuss what to do. Hines was angry when he learned that his allies were still not ready, and that most of their men had still not been told what was going on. He was starting to wonder if the Sons of Liberty were all bark and no bite, but he was already in for a penny so he might as well be in for a pound. He initially gave them another three weeks to prepare for an August 16 uprising, then pushed it back further to August 20 when the Copperheads were still hesitant, before finally agreeing to stick with the original revised plan and strike during the Democratic National Convention.

This time, the delay would prove fatal to their plans.

It turns out the leaders of he Sons of Liberty had vastly overestimated how many of their men were ready to take up arms against the Republicans. Oh, sure, they had been perfectly willing to join an anti-war pro-Democrat secret society, but talk of actual armed revolution made them queasy. When the Grand Commanders started handing out rifles and bombs and administering loyalty oaths, many of them went straight to the authorities to rat them out.

One of those informants was Felix Stidger, the Secretary General of the Grand Council of Indiana, who had actually been informing on the organization for years. Thanks to Stidger and others like him the Union quickly learned everything there was to know about the Great Northwestern Conspiracy. It sprang into action.

Judge Joshua Fry Bullitt, the Grand Commander of Kentucky, had gone to Canada after the July 20 meeting to get funds for his operation from Jacob Thompson. On his way back to Kentucky the judge was stopped by soldiers, who discovered he was carrying a sack filled to the brim with gold coins and a check for $5,000 drawn on known Confederate accounts in Montreal. Bullitt was arrested, but not before he helped his traveling companion escape so he could go warn other Sons of Liberty. Too bad that traveling companion was Felix Stidger.

Kentucky was out.

Around the same time, Grand Commander Harrison H. Dodd of Indiana realized he had to start letting the rank-and-file know what was expected of them. He went to Joseph J. Bingham, the chairman of the state Democratic committee, and asked him to help coordinate the uprising. Bingham angrily refused, then went to gubernatorial candidate Joseph E. McDonald to see if he knew about this. McDonald did not, and the two men resolved to shut the plan down. First, they made Dodd convene a public meeting of the Sons of Liberty, where they ambushed their assembled leaders and made them swear an oath to not overthrow the government of the United States. Then, just in case those oaths proved to be worthless, they leaked word of the plot to the local papers, which published breathless exposés of the Sons of Liberty and their activities. Governor Morton read those stories and sent the state police to raid Dodd’s offices, where they discovered guns and ammunition hidden in crates labeled “Sunday school books” and “Gospel tracts.”

Indiana was out.

On August 21 Stovepipe Johnson was accidentally shot in the head by his own men, blinded, and captured by Union soldiers. There would be no cavalry raid.

The Confederate Army was out, too.

Back at Camp Douglas, Col. Sweet received a letter from an officer in Detroit who had been given inside information about the plot, and explicitly naming the men on the inside who were working with the conspirators. Sweet had them promptly thrown into solitary. Back in Canada, Hines found the informant and had him thrown over Niagara Falls.

Illinois was not out, but it was forewarned.

It was hardly alone. At one point, while Hines was coordinating with Sons of Liberty in Indiana, he was alerted that Federal agents were coming to arrest him and only escaped by the skin of his teeth. It should have been a big clue that the Union was watching him closely.

Astoundingly, Capt. Thomas Henry Hines was not out.

A Hard Choice

On August 24, 1864 Hines and his hand-selected crew of sixty agents gathered at a farmhouse outside Toronto… where they were surprised to be joined by Jacob Thompson and twenty complete strangers he had invited to observe the proceedings. Hines furiously tore into his boss, but it was too late now. He just had to press on and hope none of the observers was a Union spy. (Some of them definitely were.)

Each of the Confederates was issued a pistol, $100 in cash, and a round-trip rail ticket to Chicago. They traveled in groups of two and three and checked into hotels all over the city. On August 28 they reconvened at Hines’ suite in the Richmond House hotel, which was posing as the “the Missouri delegation” to the Democratic Convention, for one final pre-operation check-in.

Except now the Sons of Liberty didn’t want to go through with it.

It was clear to everyone that the authorities were on to them. Bullitt was in jail. Dodd had only avoided arrest thanks to a last-second tip. Stovepipe Johnson was in a prisoner-of-war camp infirmary. Union forces were massed in the streets to keep order during the convention, and more than a thousand new recruits had been sent to reinforce Camp Douglas.

Also, as it transpired, many of them had still not told their rank-and-file members what they were up to, much less arm and train them. Or bring them to Chicago.

They wanted out.

Hines was livid, but resisted the urge to shoot everyone in the room and counted to ten. He took stock of the situation and asked his co-conspirators to come back after he had some time to think.

The following morning he proposed a simplified operation: a single attack on Rock Island, which held fewer prisoners-of-war but was not as heavily defended as Camp Douglas. The freed Confederate prisoners could still help the Sons of Liberty seize local arsenals and march on the state capital in Springfield. All he needed was 500 fighting men.

The Sons of Liberty did not have 500 fighting men.

Hines calmly asked if they could raise 200 fighting men. They said they would try.

They came back a few hours later with 25 fighting men and profuse apologies. They suggested that maybe they could push everything back to Election Day. They would be ready this time, for sure.

Hines kicked them out of his suite and busted open the mini-bar.

Years later, he would recognize that he had no one to blame for the mess but himself. He had expected military discipline from civilians. He had expected anti-war activists to take up arms. He had forgotten that his allies’ goals were not his own.

(Just to drive home the point, across town at the convention Clement Vallandigham persuaded the party to add an anti-war plank to its platform, which presidential nominee Gen. George B. McClellan immediately repudiated.)

The Show Must Go On

Right now, though, Hines had to offer his men a hard choice. They could stay with Hines, they could head South, or they could go back to Canada. Twenty-two of them chose to remain with Hines and engage in a campaign of terror and sabotage.

Col. Grenfell was feeling ill, so he stayed in Carlyle, Illinois to drill the Copperheads there.

Capt. Castleman took some men down to St. Louis, where the army had some transports tied up at the wharf. Security was terrible — civilians were freely allowed to board the boats at will — so it was child’s play to sneak on board, smash open a few flasks of Greek fire, and set them ablaze. They hit about a dozen before calling it quits, and were glad to get that. It turns out that Bocking’s Greek fire was temperamental; it frequently did not work at all and when it did it was no harder to put out than regular fire. Castleman grumbled that “a box of old-fashioned matches” would have done better.

Castleman reunited with Hines and they all went to Mattoon, Illinois to set fire to army storehouses there. Then one of the Confederates got so drunk he confessed to everything in a saloon. Soldiers raided their hideout and Hines barely escaped; Castleman did not. Hines felt so bad about it he had an escape kit bound up in a Bible and sent to his friend in prison. Castleman wound up not needing it; he was freed in a prisoner exchange a few weeks later.

The Trials for Treason in Indianapolis

While Hines and Castleman were terrorizing the countryside, their co-conspirators were being rounded up. Harrison H. Dodd, William A. Bowles, and four other leaders of the Indiana chapter of Sons of Liberty were arrested for treason and put on trial in Indianapolis.

At first, they treated the trial like a joke, and why shouldn’t they? The charges were a combination of strange things they actually did which were not necessarily illegal, and wild-eyed accusations of treason right out of the government’s most paranoid fever dreams. On the first day of court they laughed and smirked, until the prosecution called its first witness… Felix Stidger.

Then they went white as a sheet.

Their subsequent behavior was telling. Dodd escaped by trying together some bedsheets and climbing out a second story window, then fled to Canada. Bowles tried to get his wife to smuggle bowie knives and bribe money into jail, but the hapless Mrs. Bowles was caught each time.

The trial did not take long and all six were convicted (Dodd in absentia), three of them sentenced to death. Thanks to the negative publicity from the trial, the Sons of Liberty officially disbanded on September 17, 1864.

Election Day Sabotage

Meanwhile, Capt. Hines decided to make one last run at Camp Douglas on Election Day. The plan was virtually the same, attack Camp Douglas and free its prisoners-of-war, though there would be no attempt to seize the state capitol and only minimal support expected from local Copperheads.

This time the team consisted of Hines and only three other agents, including Grenfell. He worked closely with former Chicago-area Sons of Liberty, most notably Cook County boss Charles Walsh, who owned a farm only a block away from Camp Douglas. He made damn sure they were trained and ready.

Alas, keeping the plan small did nothing to stop leaks. Former Son of Liberty Maurice Langhorn had been spying on them for the Union the entire time. Col. Sweet also sent his own double agent, John Shanks, a prisoner-of-war who had fallen in love with a camp nurse. Shanks was allowed to “escape” from the camp, make contact with conspirator J.F. Betterworth, and ply him with whiskey until he spilled the beans.

On November 7, the night before the election, the army rounded up the conspirators. Walsh’s farm was raided and a large cache of weapons was discovered. Grenfell was arrested in his sickbed — he had come down with an attack of malaria — with a warning from Hines sitting unread on his bedside table.

Hines and co-conspirator Vincent Marmaduke managed to escape the roundup and made their way to the home of Copperhead Dr. Edward W. Edwards. The army eventually tracked him there but Hines saw them coming, barged into the bedroom of Dr. Edwards’ sick wife, slit open her straw mattress, and crammed himself into it. Soldiers searched the house and picked up the sleeping Marmaduke… and then left two guards outside, just in case Hines decided to show himself again.

The wily Hines spread rumors that Dr Edwards’ wife was on her deathbed, mingled with friends and family members coming to pay their final respects, and then waltzed out the front door undetected. Then he hopped on a train to Cincinnati, crossed back into Kentucky, and hid out there for the rest of the war, all four months of it.

That was finally the end of it.

Aftermath

After the war the conspirators were hunted down and punished and got their just desserts… oh, who am I kidding? This is America. Most of them went completely unpunished. Those who had been convicted were pardoned or had their sentences commuted. Others just hid out in Canada or Europe until President Andrew Johnson issued a blanket amnesty for ex-Confederates in 1868.

I would like to say they went on to have small, undistinguished lives… but many of them went on to be relatively prominent figures at the local, state, and even national level. Some of them, like Hines, wrote self-serving biographies that provided the basis for this episode.

There were two major exceptions.

George St. Leger Ommaney Grenfell’s luck had finally run out. He had been captured as a soldier, he had been arrested as a spy, he had violated his oath to not take up arms against the United States, and he had personally embarrassed Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. His nationality would not save him this time. He was convicted by a military tribunal and sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment. Stanton was determined to give Grenfell the most painful prison term possible, so he was packed off to Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas and thrown into a cell with Dr. Samuel Mudd. Grenfell rotted away for years, far longer than he ought have, and by 1868 he was the only Confederate of any importance in any prison anywhere. (Even Jefferson Davis had been paroled for good behavior by then.) Eventually Grenfell decided to escape. He and three other prisoners bribed the guards, climbed over the walls, and rowed to freedom in Havana. At least, that was the plan. They were never seen again, and were assumed to have drowned at sea.

Clement Vallandigham was driven out of politics and returned to his law practice. On June 17, 1871 he was in Lebanon, Ohio defending an accused murderer. While demonstrating how the victim could have shot himself in the stomach while drawing the murder weapon from his pocket, he accidentally shot himself in the stomach while drawing the murder weapon from his pocket. He died later that day, though on the plus side the jury found his client not guilty.

I can’t think of a better metaphor for this whole operation than accidentally shooting yourself with your own gun. Can you?

Connections

For another example of secret societies and politics mixing, look no further than the anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant Order of the Star-Spangled Banner, better known to history as the “Know-Nothings,” who took over the tiny American Party when the Whigs collapsed in the late 1840s and early 1850s. (“Miss Bunkley’s Book”)

If the idea of violent agitators streaming over the Canadian border sounds familiar, it should. It’s just that last time all that traffic was heading in the other direction, when Canadian dissidents and American opportunists poured over the border during the “Patriot War” of 1838-1840. (“Dangerous Excitement”).

Colonel George St. Leger Ommany Grenfell is hardly the first person to completely exaggerate his military achievements. Two other standout examples of stolen valor are Confederate commerce raider George Canning, who couldn’t decide whether his war wounds were from the Crimea or Shiloh (“Shenandoahs: The Sea King”); and artist James McNeill Whistler, who made himself sound like a South American revolutionary instead of a passive observer to the revolution (“Crepuscule in Blood and Guts”).

(Also, you really should read more about Grenfell — his story is utterly bonkerys. If you can get a hold of it, Stephen Z. Starr’s Colonel Grenfell’s Wars is definitely worth checking out.

A lot more than Confederate informants have gone over Niagara Falls over the years. Men in barrels, women in barrels, Sam Patch “The Jersey Jumper”, a barge full of circus animals, the steamship Caroline (“Dangerous Excitement”)… and baseball player Ed Delahanty (“Triple Jumper”).

Sources

- Ayer, I. Winslow. The Great Northwestern Conspiacy in All Its Startling Details, Illustrated With Portraits of Leading Characters. Baldwin and Bamford, 1865.

- Balsamo, Larry T. “‘We Cannot Have Free Government without Elections’: Abraham Lincoln and the Election of 1864.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Volume 94, Number 2 (Summer 2001).

- Beauregard, Erving E. “The Bingham-Vallandigham Feud.” Biography, Volume 15, Number 1 (Winter 1992).

- Benton, Elbert Jay. The Movement for Peace Without Victory During the Civil War. Western Reserve Historical Society, 1918.

- Coffman, Edward M. “Captain Hines’ Adventures in the Northwest Conspiracy.” Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Volume 63, Number 1 (January 1965).

- Crenshaw, Ollinger. “The Knights of the Golden Circle: The Career of George Bickley.” American Historical Review, Volume 47, Number 1 (October 1941).

- Dew, Charles B. Apostles of Disunion: Southern Secession Commisioners and the Causes of the Civil War. University of Virginia Press, 2001.

- Fesler, Mayo. “Secret Political Societies in the North during the Civil War.” Indiana Magazine of History, Volume 14, Number 3 (September 1918).

- Horan, James D. Confederate Agent: A Discovery in History. Pickle Partners, 2015.

- Johnston, Steven. “Lincoln’s Decisionism and the Politics of Elimination.” Political Theory, Volume 4, Number 4 (August 2017).

- Keehn, David C. Knights of the Golden Circle: Secret Empire, Southern Secession, Civil War. Louisiana State University Press, 2013.

- Klement, Frank L. “Carrington and the Golden Circle Legend in Indiana during the Civil War.” Indiana Magazine of History, Volume 61, Number 1 (March 1965).

- Klement, Frank L. “Civil War Politics, Nationalism, and Postwar Myths.” The Historian, Volume 38, Number 3 (May 1976).

- Klement, Frank L. “Copperhead Secret Societies: In Illinois during the Civil War.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Volume 48, Number 2 (Summer 1955).

- Mackey, Thomas C. Opposing Lincoln: Clement L. Vallandigham, Presidential Power, and the Legal Battle over Dissent in Wartime. University Press of Kansas, 2020.

- Markle, Donald E. Spies and Spymasters of the Civil War. Hippocrene Books, 1994.

- Mayers, Adam. Dixie and the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the Union. The Dundurn Group, 2003.

- McPherson, James M. “No Peace without Victory, 1861-1865.” American Historical Review, Volume 109, Number 1 (February 2004).

- Morrow, Curtis Hugh. “Politico-Military Secret Societys of the Northwest.” Social Science, Volume 4, Number 1 (Winter 1928-1929).

- Pitman, Benn. The Trials for Treason at Indianapolis, Disclosing the Plans for Establishing a North-Western Confederacy. News Publishing Company, 1865.

- Rodgers, Thomas E. “Copperheads or a Respectable Minority: Current Approaches to the Study of Civil War-Era Democrats.” Indiana Magazine of History, Volume 109, Number 2 (June 2013).

- Sanders, Charles W. While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

- Schultz, Duane. The Dahlgren Affair: Terror and Conspiracy in the Civil War. W.W. Norton, 1998.

- Smith, Bethania Meradith. “Civil War Subversives.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Volume 45, Number 3 (Autumn 1952).

- Starr, Stephen Z. “Colonel George St. Leger Grenfell: His Pre-Civil War Career.” Journal of Southern History, Volume 30, Number 3 (August 1964).

- Starr, Stephen Z. Colonel Grenfell’s Wars: The Life of a Soldier of Fortune. Louisiana State University Press, 1971.

- Tidwell, William A. April ’65: Confederate Covert Action in the American Civil War. Kent State University Press, 1995.

- Van der Linden, Frank. The Dark Intrigue: The True Story of a Civil War Conspiracy. Fulcrum Publishing, 2007.

- Van Doren Stern, Philip (editor). Secret Missions of the Civil War. Portland House, 2001.

- Weber, Jennifer L. “Lincoln’s Critics: The Copperheads.” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Volume 32, Number 1 (Winter 2011).

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: