A Month of Billys

was Billy Sunday good at baseball?

If you’re at all familiar with the American Evangelical movement, you have heard the name of Billy Sunday.

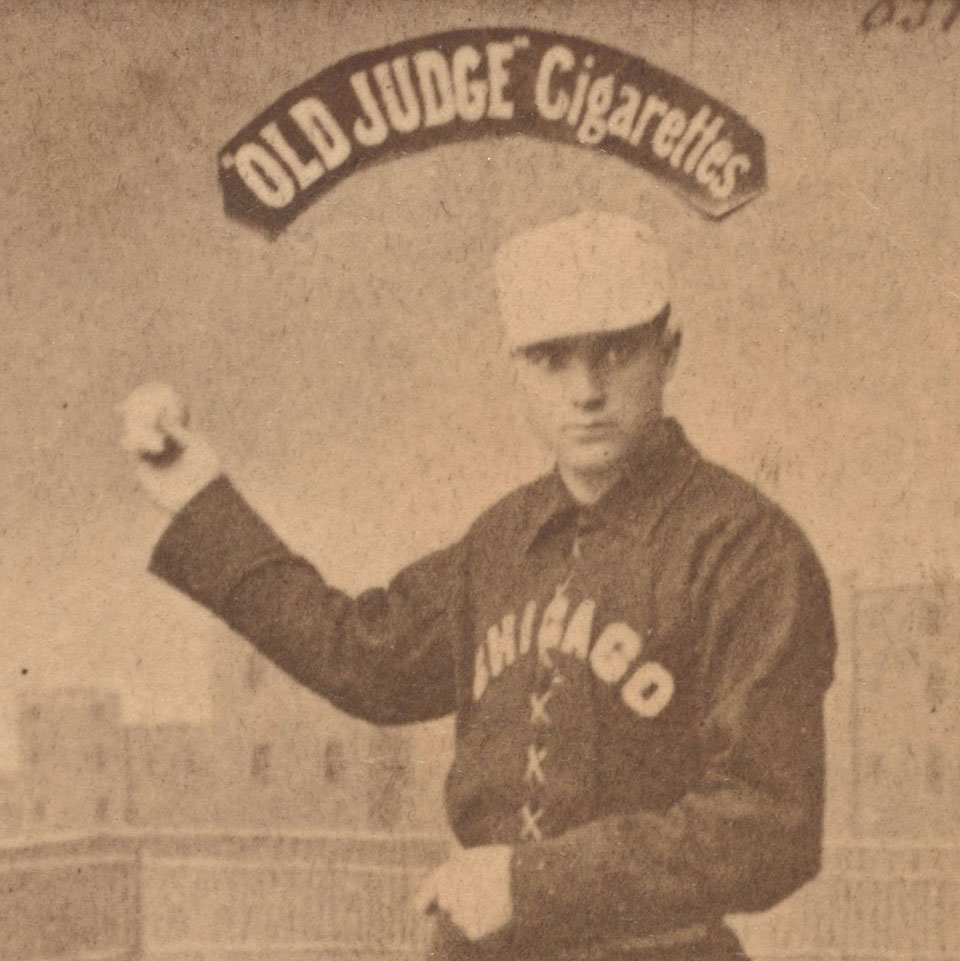

Sunday was an early baseball star who played for the Chicago White Stockings, the Pittsburgh Alleghenies, and the Philadelphia Phillies. Though never a top-tier player, his dramatic fielding style and swift base running made him a fan favorite wherever he played.

Eventually, Sunday walked away from the sport to become a preacher. He started off speaking off-the-cuff at the YMCA, and eventually worked his way up to become the advance man for revivalist J. Wilbur Chapman. When Chapman decided to settle down, Sunday took over his circuit and quickly became the most famous evangelist of early Twentieth Century America. His admirers included Henry Cabot Lodge, Woodrow Wilson, Herbert Hoover, and Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis.

Sunday held some surprisingly some surprisingly Progressive views for a man of his age: he called for racial harmony, fought against child labor, and supported woman’s suffrage. Yet the most part he was a fire-and-brimstone moralist who defended the status quo. He attacked the theory of evolution; demonized Germans during WWI (even though he was half-German himself); valorized the Ku Klux Klan; and once said he would “rather be in hell with Cleopatra, John Wilkes Booth and Charles Guiteau” than support striking coal miners. He was also against having fun in any form, including drinking, gambling, dancing, motion pictures, and any book other than the Bible. In fact, there was only one source of fun that met Billy Sunday’s approval: baseball. Never on the Lord’s day, of course.

There are so many facets of Billy Sunday’s life and career that beg to be explored. I could dissect his distinctive and effective rhetorical style. I could examine how his values came less from Christianity and more from a blue-blooded reactionary conservatism. I could take a deep dive into the suspicious finances of his revivals. I could gossip about how he raised his children, who spurned the Christian values he championed.

I am not going to do any of that. Instead, I want to ask: was Billy Sunday actually a good baseball player?

It’s not a trivial question. Young men and the working poor were drawn to Sunday’s revivals by the prospect of seeing a real major leaguer, and once he had his foot in that door he stepped through to sell salvation.

Sunday knew that if the general public forgot he was a ballplayer his appeal would be diminished, so he made sure to remind them of his playing days every chance he got. He was constantly throwing out the first pitch at games, hobnobbing with current and former players, and working ham-fisted baseball metaphors and anecdotes into his sermons. His crowning glory was his personal conversion narrative, where he saw the light and walked away from the major leagues at the peak of his career to spread the word of the Lord.

That’s a powerful tale, but how accurate is it? To find out we’ll have to start at the beginning.

Misery and Poverty

William Ashley Sunday was born in Ames, Iowa on November 19, 1862.

He was the third and youngest son of William Sonntag and Mary Jane Corey. His father was a farmer, but at the time of Billy’s birth he was serving as a private in Iowa’s Twenty-Third Volunteer Infantry, fighting the Confederates in far-off Missouri. The two would never meet, because on December 23, 1862 William Sonntag died of pneumonia in an Army hospital.

It was a terrible Christmas gift, and it the tone for Sunday’s childhood of misery and poverty.

Mary Sunday remarried, but was deserted by her second husband after only a few years. She couldn’t afford to raise five children on her own, so she started ridding herself of the boys from her first marriage. Fourteen-year-old Albert was old enough to work and put food on the table, but twelve-year-old Edward and ten-year-old William were sent off to live with their grandparents. That didn’t last long, and soon the two boys were were unceremoniously dropped off at the Soldiers’ Orphans Home.

(Also, while all this was going on, their eldest brother Albert was kicked in the head by a mule and became an invalid, and their half-sister Elizabeth burned to death while tending the kitchen fire.)

Eddie and Billy were not happy at the orphanage, and left as soon as they could. Now fourteen years old, Billy went right into the workforce. He was a farm hand and a bellhop before landing a sweet gig as an errand boy for Col. John Scott, the former lieutenant governor. Mrs. Scott took a shine to the handsome young lad and paid for him to attend the high school in nearby Nevada, where he made a name for himself as an athlete.

You see, Billy Sunday was fast. Really fast. How fast was he? Well, one Fourth of July he entered a hundred yard race with a $3 cash prize. He hadn’t known there was going to be a race until the day of, and despite his lack of training (and shoes) he left all the other competitors in the dust.

Feats like that brought Billy to the attention of the Marshalltown Fire Brigade. Back in the day fire-fighting tournaments were a big deal, pitting local fire departments against each other in tests of job-related skills and general athletic prowess. Competitors took these tournaments very seriously, and weren’t above bringing in ringers to secure their victory.

Soon Billy was a “volunteer” for the Marshalltown Fire Brigade. Nominally, he had a do-nothing job assisting the local undertaker, but his real job was to train full-time for the next firefighting tournament.

That still left Billy with more free time than he knew what to do with, so he started playing baseball. Turns out he was a natural. In 1882 Billy led his team to a thrilling victory over a heavily favored team from much larger Des Moines, scoring five runs and making numerous spectacular catches in the outfield.

The game was the talk of Marshalltown for days. Weeks. Months, even. They were still talking about it in December, when the city’s favorite son came back to visit his parents for Christmas.

That favorite son would be one Adrian Constantine “Cap” Anson, first baseman, team captain, and manager of the Chicago White Stockings. When Anson’s parents wouldn’t shut up about the local team’s star player, he decided to see what all the fuss was about. Anson was impressed, and offered the young man a contract to play in the majors for $60/month.

Billy couldn’t sign on the dotted line fast enough.

The Best Baserunner in the Whole League

Billy Sunday reported to Chicago’s Lakefront Park in April 1883. He was flat broke and wearing everything he owned, in this case, an ill-fitting sage green suit that cost him $6. The other White Stockings had a good laugh at the poorly dressed hick who thought he could play major league ball, but they stopped laughing when Billy challenged the fastest man on the team to a hundred yard race and beat him by a good fifteen yards.

They could use a man with speed like that.

Could, but didn’t. Billy was the backup outfielder on a world-class team which had just won back-to-back-to-back pennants with a stacked lineup that included two future Hall of Famers in the form of Cap Anson and King Kelly. They just didn’t need his services that often.

Billy appeared in only fourteen games in his rookie year. His only “accomplishment” of note was kicking off the season with thirteen consecutive strikeouts. He took too many risks on the field and in the base paths, trusting that his speed would win the day. Frequently, it did not. He committed numerous errors on balls he should have been able to reach, and was caught stealing more often than not.

Fortunately for Billy, his position was secure. His teammates liked him and manager Cap Anson considered him a bit of a pet project. Even owner Al Spalding was on Billy’s side, holding up Billy’s humble demeanor and Christian values as an exemplar for other ball players to follow.

Billy became a fixture of the White Stockings lineup over the next several years, appearing in about forty games each season. He became known for his range in the outfield, his spectacular diving catches, and for being a holy terror on the base paths. Assuming he could get on base in the first place that is; he never quite figured out major league pitching.

When he wasn’t penciled into the lineup Billy acted as the team gopher. He held on to the petty cash, made travel arrangements for road trips, managed the team’s equipment, and took care of whatever odd jobs needed doing.

Cap Anson also put Billy to work as a special attraction, arranging pre-game races against the opposing team’s fastest runner. Billy didn’t always win, but he always put on a good show.

Then Anson began making cash wagers on the races, sometimes as much as $1,000. That didn’t sit well with Billy, who considered gambling immoral. Once he tried to talk his way out of a race against Arlie Latham of the St. Louis Browns, but Anson won him over with a spurious motivational speech.

I’m not much on religion, but I don’t believe that God wants you to start out with him by throwing down your friends, on a contract that you took before you went with him. Now, I tell you what you do. You go down to St. Louis and run that race, and you can fix it up with God afterward.

Billy did what he was told, but it left a sour taste in his mouth for years.

Despite his limited playing time, Billy was popular with White Stockings fans. Young ladies, in particular, swooned over his clean-cut handsome face. Billy, though, only had eyes for one woman: Helen “Nell” Thompson, older sister of the team’s bat boy. They began dating.

That didn’t sit well with Nell’s father. He did not want her dating a baseball player who worked as a firefighter in the off season. Neither career was stable, and they tended to attract men who were drinkers, fighters, and flirts. To Billy’s credit, he straightened up his act considerably and began attending Sunday services at the Jefferson Park Presbyterian Church. Nell’s father wasn’t fully won over, but his grumbling became noticeably quieter.

Greatest Thing I Ever Saw!

Now, Billy may have cut back on the drinking, fighting, and flirting, but he didn’t cut it out completely. One evening in June 1886 the team went on an epic bar crawl after winning a home series against the New York Giants. Towards the end of the night they found themselves at the corner of State and Van Buren, and sat down on the curb to sober up.

A horse-drawn gospel wagon was parked nearby and a Salvation Army choir was singing hymns to a small crowd. Maybe it was the Lord, maybe it was the booze, but Billy was moved. He sat on the curb, singing along, tears streaking down his cheeks. When the missionaries invited the crowd to follow them to a nearby church he stood up, dusted off his coat, and announced to his teammates: “Boys, it’s all off. We have come to where the roads part.”

When Billy showed up at Lakefront Park the next day, he was expecting to be ribbed, and was pleasantly surprised when his teammates were supportive. Even King Kelly, the team’s most notorious roisterer, clapped him on the back and proclaimed, “Bill, I’m proud of you. Religion ain’t my long suit, but I’ll help you all I can.”

At first, getting right with the Lord seemed to be great for Billy. His relationship with Nell improved, he had more pep in his step, more power in his swing.

This period of his life is probably best exemplified by his famous “prayer catch.”

Now, there are a lot of versions of this story, most of which have been exaggerated with to make them more dramatic. I’m going to give you the most accurate version I’ve been able to piece together.

It’s July 10, 1886 and the White Stockings are playing the Detroit Wolverines. Chicago is up 2-0 at the top of the fifth, but Detroit is threatening with runners on 2nd and 3rd and their best hitter, Charlie Bennett, stepping up to the plate. Pitcher John Clarkson seems to have things in hand, but stumbles during his release and sends a fat pitch right over the middle of the plate. Bennett pounces and smacks it into deep right field.

Billy gets a good read on the ball and starts sprinting at top speed, but it’s headed outside of the play area and into the fans in right field. (At this point there are no outfield walls, so the edges of the field are marked with chalk lines or ropes, and everything after that is festival seating.) It’s going to be hard to get this one, so Billy dashes off a quick prayer to his creator.

God, I’m in an awful hole. Help me out, if you have ever helped mortal man. Help me get that ball. And you haven’t much time to make up your mind, either!

Well, the Lord makes up his mind and the crowd parts in front of Billy like he was Moses parting the Red Sea. He takes one last glance over his shoulder, makes a desperate dive, snags the ball, and tumbles to a stop beneath a team of horses. The crowd is silent in breathless anticipation.

When Billy pops up holding the ball, the crowd goes wild. Gambler Tom Johnson, the former mayor of Cleveland, immediately runs up to the outfielder and stuffs a $10 bill in his hand, proclaiming: “Greatest thing I ever saw! Buy yourself the best hat in Chicago! That catch won me $1500!”

Billy is beaming. This is the greatest play he’s ever made, and proof that God is on his side. “I believe the Lord helped me get the ball that day because I was trying to trot on the square for him.” (He does not question why the omnipotent creator, his only begotten son, and their little bird friend would care about the outcome of a sporting event. Athletes never do.)

Alas, the Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. A few weeks later Billy was injured and benched for the rest of the season. He had to watch from the sidelines as his team won the pennant, only to go down in flames in the World’s Championship Series against the St. Louis Browns of the American Association.

That was the swan song of Cap Anson’s Chicago White Stockings dynasty. In the off-season Al Spalding sold off King Kelly and the rest of the team’s top players. Spalding claimed he was just trying to clean up the team, get rid of the drinkers and gamblers and reprobrates, but really it just came down to the money.

As usual, Billy’s spot was secure, and as a result he saw more playing time than ever during the 1887 season, some fifty games. He stepped up to the plate, hitting a career-best .291 and stealing 34 bases. His new teammates didn’t do nearly as well, and the team finished in third place behind the Detroit Wolverines and Philadelphia Quakers.

Billy was starting to pull away from the game at this point. At Nell’s urging, he was taking classes in rhetoric and theology at Northwestern University, serving as the school’s baseball coach in lieu of tuition.

On New Year’s Day 1888 Billy finally proposed to Nell, and she accepted. Her father begrudgingly gave the couple his blessing. Billy may have been a degenerate ballplayer, but he was one of the good ones.

Long-Term Loan

Now, the Lord never gives you more than you can handle, but he threw the newly engaged couple a curveball in early February when they learned that Billy had been traded to the Pittsburgh Alleghenies.

Spalding and Anson told Billy the deal was conditional on his approval, and he was sorely tempted to stay — Anson and the White Stockings were like family by now — but Spalding either could not or would not pay him even half of what the Alleghenies were offering and Billy was planning on starting a real family. He packed up his bags and reported to Recreation Park in Pittsburgh.

The Alleghenies were not like the White Stockings at all. The team just plain sucked, and struggled to win games. The players were less disciplined, rowdier, and not inclined to hang out with a holy roller like Billy.

Billy was a starting player now, and made the most of it. He appeared in a career high 120 games, and while he still couldn’t hit for beans, his fielding was spectacular and he somehow managed to steal 71 bases.

The highlight of his season came on September 5. The Alleghenies were in Indianapolis playing the Hoosiers, but Billy was scratched from the lineup so he could take a train up to Chicago and finally get married to Nell. He was given a hero’s welcome at the train station. After the ceremony, Anson and Spalding set up special box seats for the happy couple at that afternoon’s White Stockings game.

That was their entire honeymoon. The very next day the couple went back to Indianapolis, and Billy suited up to play.

The Alleghenies still sucked, and finished in sixth place, two games under.

Billy continued to pull away from the game. He taught Sunday school whenever the Alleghenies were at home in Pittsburgh, and gave lectures about religion and morality at the local YMCA whenever they were on the road. He drew huge audiences, though they were more interested in baseball stories than salvation. After the season ended he started working part time for the YMCA, though the salary was even less than the pittance he’d been earning as a fireman.

Meanwhile, Cap Anson had a bad case of seller’s remorse. He hadn’t wanted to trade Billy in the first place, and the boy had really shown what he was capable of when he was given a chance to play every day. The Alleghenies were happy with their acquisition and did not want to make another trade, so Anson began arguing that there had never been a trade in the first place — just a “loan” which he was now calling due. His rhetorical tricks didn’t work, and the people of Chicago wound up wondering why their manager was so hung up on a middling player like Billy Sunday.

Billy’s 1889 season was unremarkable. He played forty fewer games, though his numbers were about what’d you’d expect if you pro-rated his 1888 performance.

1890, though, now that was a different story. That year the National League had to contend with the upstart Player’s League, which lured away most of the top talent with the promise of more money. Billy was one of the few players who didn’t jump from the Alleghenies to play for their Player’s League equivalent, the unimaginatively named Pittsburgh Burghers. The Alleghenies were left with a lineup of washed-up has-beens, unproven rookies, and “trolley leaguers” with no business being anywhere near the majors.

As usual, Billy Sunday rose to the occasion. He still couldn’t hit major league pitching for beans, but he wasn’t facing major league pitching any more. He improved his batting average by twenty points and stole bases like they were going out of style. He even got to be a relief pitcher once — though he gave up two walks, a double, and a triple before he was yanked, giving him an ERA of, uh, infinity. Mid-season he was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies, and finished his season there.

You Promised God To Quit

During the off-season, Billy had a hard choice to make. He was offered a full-time position working for the YMCA; it paid far less than a baseball player’s salary, but he could no longer deny he was being called to the ministry.

There was only one problem: he was still under contract to the Philadelphia Phillies for several more years. He politely asked them for his release, but reassured them that if they did not grant it by he would show up at the Baker Bowl on April 1 ready to play.

Winter flew by with no word from the Phillies, and Billy turned to prayer. “Lord, if I don’t get my release by March 25th, I will take that as assurance you want me to continue to play ball; if I get it before that date I will accept that as evidence you want me to quit playing ball and go into Christian work.”

The Phillies ultimately granted Billy Sunday his unconditional release on March 17, 1891. Divine providence had nothing to do with it; the Player’s League had folded after only one season and now teams could afford to pick and choose who they wanted to keep.

Of course, immediately after that the Cincinnati Red Stockings offered to give Billy $500 a month to play outfield, more than the Phillies had been offering. He was sorely tempted to take that offer, but Nell laid down the law. “There is nothing to consider; you promised God to quit.”

And that was how Billy Sunday left baseball to become a preacher. There’s far more to the story, of course, but we’re ending it here.

Cold Hard Stats

So, let’s get back to the real question: was Billy Sunday a good ballplayer?

Billy Sunday certainly thought he was. He was constantly reminding people that he was “the fastest baserunner who ever played the game,” that he could run the bases in 14 seconds flat, that in one season he batted .359 and in another he stole 95 bases.

Could he run the bases in 14 seconds flat? Hard to say. He was never officially timed, and his career ended before the advent of motion pictures so he was never filmed either. In the 1890s the world record for the 100 meter dash was about 10.8 seconds. Rounding the bases is 120 yards, which is basically a 100 meter dash with some sharp cornering that would slow a runner down. It’s definitely possible, especially in those days of crude hand-timing, but also unlikely.

Did Billy ever hit .359? Not even close. The closest he ever came was some 74 points lower, when he batted .291 in 1887, and if you discount that one anomalous season, his lifetime batting average was about .243. If Billy ever hit .359 it was playing sandlot baseball back in Marshalltown, and pro-am records don’t count because the skill differential between players is too great.

He didn’t steal 95 bases either. I’m not sure why he’s lying about that, because still stole enough bases to appear twice on the all-time single-season stolen base leaders: tied at 50th for the 84 bases he stole in 1890, and tied for 114th for the 71 bases he stole in 1888.

Was he the fastest man in baseball? Of course not. There’s only one fastest man in baseball, and that’s Cool Papa Bell. Cool Papa Bell was so fast he once smacked a line drive up the center and got hit by the ball as he was sliding into second. Cool Papa Bell was so fast that he could hit the switch and be under the covers before the lights went out. Cool Papa Bell was so fast he once vibrated into another dimension and had to fix the tear in the space-time continuum with the help of the Golden Age Cool Papa Bell.

Joking aside, Billy Sunday was hardly the fastest man in baseball.

Don’t get me wrong, 84 stolen bases are nothing to sneeze at, but Billy was only able to run up those numbers in 1890, when anyone with actual talent had jumped ship to the Player’s League and he was up against whatever group of misfits the other National League owners had managed to round up. And he wasn’t even the fastest player in the league that year! His Philadelphia Phillies teammate Billy Hamilton stole 102 bases, Harry Stovey of the Boston Reds stole 97 bases, and Hub Collins of the Brooklyn Bridegrooms stole 85.

When you look at the all-time list of single season stolen base leaders, you can’t help but notice that it’s dominated by players from the 1880s and 1890s. The game was vastly different back then — outfields were cavernous, gloves were primitive, and speed was king. Billy was fast, but not even close to the fastest.

His total of 246 career stolen bases puts him at 247th on the all-time list of career stolen bases, putting him in the illustrious company of players like Garry Maddox, Tony Fernandez, Stan Javier, and Andy Van Slyke. Great guys, but not exactly speedsters.

To be blunt, Billy was an average player at best. His fielding was slightly above average, his base running was good, and his hitting was meh at best. Throughout his career his Wins Above Replacement vacillated between -0.4 and 1.3. That makes him a solid utility player, but not a superstar.

If you look at the numbers season-by-season, Billy’s hitting peaks in 1887 and declines in steadily in 1888 and 1889, only to be given a mild bump against weak opponents in 1890. His base running peaks in 1888 and shows a similar decline. At the same time, his fielding gets progressively worse — his fielding percentage and range factor stay about the same, while the number of errors he commits steadily increases disproportionate to his amount of actual playing time.

This puts the lie to the heart of Billy Sunday’s conversion story. He wasn’t some superstar who walked away from the game at the peak of his ability. He was an aging journeyman who left before he could be shown the door. There’s nothing wrong with that! One of the secrets to having a good life is knowing when to quit.

Then again, when you’ve made a promise to God to quit you damn well better quit. The big man does not like to be left hanging.

Connections

Sunday wasn’t the last ballplayer whose only selling point was speed. For two seasons in the mid-1970s, the Oakland Athletics experimented with using college track star Herb Washington as a “designated runner.” We talked about this disastrous experiment in the episode “Hurricane Coming Through.”

For another ballplayer who put up impressive numbers (but only against weak competition), check out the story of Johnny Dickshot, the self-professed “Ugliest Man in Baseball”, who looked like an All-Star in the 1940s… but only because all the superstars were off fighting Hitler and Tojo.

The owner of the 1890 Philadelphia Phillies? Once again it’s the famously parsimonious Colonel John Ignatius Rogers, who has shown up in an improbable number of episodes including “French Leave” (about Nap Lajoie’s complicated contract situation), “Triple Jumper” (about the mysterious death of Ed Delahanty), and “The Buzzer Brigade” (about the earliest use of electronic devices to cheat at baseball).

Sources

- Brown, Elijah P. The Real Billy Sunday. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1914.

- Bruns, Robert A. Preacher: Billy Sunday & Big-Time American Evangelism. New York: W.W. Norton, 1992.

- Corbin, David A. Life Work and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: The Souther West Virginia Miners, 1880-1922 (Second Edition). Morgantown: University of West Virginia, 2015.

- Hankins, Barry. Jesus and Gin: Evangelicalism, the Roaring Twenties and Today’s Culture Wars. New York: Palgrave Macmillan: 2010.

- Juliano, William. “The Evangelical Outfielder: Billy Sunday’s Rise from the National League to the National Consciousness.” The Captain’s Blog, 22 Dec 2010. http://www.captainsblog.info/2010/12/22/the-evangelical-outfielder-billy-sundays-rise-from-the-national-league-to-the-national-consciousness/4379/ Accessed 2/17/2021.

- McLoughlin, William G. Jr. Billy Sunday Was His Real Name. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955.

- Sowell, Mike. July 2, 1903. New York: Macmillan, 1992.

- “Billy Sunday.” Baseball Reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/sundabi01.shtml Accessed 2/17/2021.

- “Single-Season Leaders & Records for Stolen Bases.” Baseball reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/SB_season.shtml Accessed 1/1/2023.

- “Sporting affairs.” Chicago Tribune, 13 Mar 1886.

- “Ball notes.” Nashvillle Banner, 5 May 1886.

- “Van’s victory.” Oakland Tribune, 29 Jun 1887.

- “Athletes at the ball park.” Chicago Tribune, 23 Jul 1886.

- “Answers to correspondents.” Chicago Inter-Ocean, 31 Jul 1887.

- “Gossip about Ball-Players.” Chicago Tribune, 15 Jul 1888.

- “Another good man signed.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 18 Jan 1888.

- “Sporting.” Pittsburgh Press, 9 May 1888.

- “He stands alone.” Pittsburgh Press, 11 Sep 1888.

- “Sunday is now a Quaker.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 23 Aug 1890.

- “Sunday’s retirement.” Pittsburgh Dispatch, 31 Aug 1890.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: