Burning Fire, Deep Water

neither Venezuelan nor Volcano

The Venezuelan Volcano

Walter Wanger was going to make the biggest damn movie Hollywood had ever seen.

His adaptation of Arabian Nights was going to kick off Universal’s 1943 season and set the tone for the rest of the year. This movie would have something for everyone! The thrilling athleticism of Sabu! The exotic beauty of Maria Montez! And, to bring the laughs, Shemp Howard as Sinbad the Sailor! All shot in glorious, eye-catching three strip Technicolor!

And what’s the point of doing an adaptation of the Arabian Nights if you don’t have a few scenes set in the Sultan’s harem, amirite fellas? Wanger himself had spent weeks casting the most alluring and curvaceous beauties Hollywood had to offer. He had high hopes for the one he’d chosen to stand at the head of the ensemble: Burnu Acquanetta.

The sultry South American sensation had come out of seemingly nowhere. She’d been working as a waitress in New York when a photographer saw her admiring her own reflection in a window. He asked her if she was a model, and she said yes, but it turned out she didn’t have representation. The photographer immediately gave her the card of Harry Sayles Conover, who hired her on the spot and represented her as “the typical Latin American girl.”

Americans were crazy for all things South American at the time, and it didn’t take time for Acquanetta to become one Manhattan’s top models. During the day she appeared on the covers of Bazaar and Cosmo and Vogue. At night she turned all the heads at the Stork Club and the Twenty-One.

Acquanetta was squired around town by some of the city’s most eligible bachelors: Orson Welles, Prince Aly Khan, and Ed Judson (the ex-Mr. Rita Hayworth). Millionaire hotelier Howard Johnson was so taken by her beauty he proposed to her every day. Walter Winchell dubbed her the “Venezuelan Volcano.”

Soon, the Latin lovely was offered a lucrative job at the Copacabana in Rio de Janeiro. Her trip to Brazil had a one-day stopover in Beverly Hills, so she went out to party at the Mocambo. There she caught the eye of studio moguls Louis B. Mayer and Walter Wanger, who hired her on the spot.

Wanger had high hopes for his new ingenue. She didn’t speak English all that well, but the kind of beauty she had made language irrelevant. He was going to dress her in a bewitching harem outfit and shuttle her around the country to do advance publicity for the film. He was going to put her on the film’s poster, and then showcase her in a series of ‘B’ pictures that would show off her lithe limbs and smooth caramel skin. He even ginned up a fake rivalry between Acquanetta and Maria Montez, just to get his new starlet’s name out there in the dirt sheets.

He was going to make a lot of money for Acquanetta… and himself, too. All Acquanetta had to do was go down to the offices of the Screen Actors’ Guild and get her union card.

Full-Blooded Indian Princess

Now, getting a SAG card shouldn’t have been a complicated. The union already knew that Acquanetta had landed a role in a major motion picture, and Wanger was paying her initiation fee, so all she really needed to do was show proof of identity. A birth certificate would do just fine.

There was only problem: Acquanetta didn’t have a birth certificate.

The guy at the SAG office was very understanding. It made sense that a foreign national wouldn’t necessarily have a birth certificate on her, or have an easy way to acquire a copy. Her Venezuelan passport would be more sufficient to provide proof of identity.

Ah, about that, señor…

For the next several minutes the SAG guy listened, dumbfounded, while Acquanetta poured out her life story.

She had been born on July 21, 1921 near Ozone, Wyoming. Her parents were Arapaho Indians, “Laughing Water” and “Blue Skies,” and they gave her the name “Burnu Acquanetta,” meaning “burning fire, deep water.” Alas, Acquanetta’s parents died of influenza when Acquanetta was only three, and she was taken in by another Native woman, Linda Smith.

For several years she and her foster mother lived a nomadic existence, wandering the reservations of Wyoming and Colorado and Oklahoma, but when Linda fell in love and got married, Acquanetta was sent off to live with a rich family in New England.

When Acquanetta turned 14, she ran off to join a troupe of gypsies. She worked tent shows, usually standing in as a magician’s assistant or doing song-and-dance routines. When the carnival reached New York, she became entranced by the allure of the big city and jumped ship to work as a waitress.

That wasn’t enough for her, though. She knew she was beautiful and dreamed of being model or actress. Alas, beautiful women are a dime a dozen in New York, and young Acquanetta had trouble making an impression on casting agents.

Eventually, though one of them gave her some useful advice, though: “Gee, kid, they’re crazy for South Americans now. You could pass as one easy if you only had an accent.”

Well, why not? It was definitely true that Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor” policy had driven New Yorkers nuts for everything South American. Acquanetta had dusky skin and ethnically ambiguous features. She could easily pass as an exotic Latin type.

So, she took a room with a family in Spanish Harlem and spent every spare minute trying to copy the way they spoke. And it seemed to work! Soon she was working the city’s most exotic nightclubs, carousing with South American expatriates who thought she was one of her own.

One slight problem, though: she didn’t speak a word of Spanish. If anyone ever tried to engage her in conversation in her supposed native tongue, she’d try to brush it off: “My Eenglish, eet ees so bad, I need to practice — let us not talk Spanish.”

Soon Acquanetta had the confidence to stride into the Conover Modeling Agency, who fell for her act hook, line and sinker. Conover soon made her the most popular model in town, but Acquanetta, looking for new worlds to conquer, set her sights on Hollywood. After all, they were just as crazy for South Americans as New York was.

Her original plan was to travel to Mexico or Venezuela, get a foreign passport, and then return to the California and start looking for work. Unfortunately, on the train out west she bumped into super-agent Charles Feldman, who fell in love with her look at first sight. When Feldman reached Hollywood, he phoned up Walter Wanger and pitched her for a role in Wanger’s latest movie.

Walter, I’ve found something you won’t believe until you see it! But ravishing! You know what I mean? Dark, sultry, explosive, colossal! Fresh out of Venezuela — that’s in South America — via the Powers agency — that’s in New York! She is a find, Walter! You’ve got to see this baby! She is the Good Neighbor Policy but in a dream walking!

Wanger met with Acquanetta and had her sign a $1,000 contract on the spot.

And now she was here, at the offices of the Screen Actors’ Guild, begging an anonymous union functionary to maybe just approve her application anyway, and keep this stuff about her not really being Venezuelan quiet?

Well, welcome to Hollywood, Acquanetta. Within half an hour everybody in Tinseltown knew the real story.

Walter Wanger was not happy. She met with him, apologized, and claimed everything was just an innocent deception to inject a little glamour into her dull and stupid life. It must have been a very convincing apology. Wanger decided her dancing and swimming skills (and of course her beauty) were more important to the studio than where she really came from. At least now they didn’t have to pay for English lessons that Acquanetta didn’t need.

Universal switched gears and started promoting Acquanetta not as a voluptuous Venezuelan, but as a beautiful Indian princess.

In practice, all that really meant was putting out a press releases touting Acquanetta as the first “full-blooded Indian” to be featured in a motion picture. (Really? Lillian St. Cyr would like a word, boys.) They also snapped some publicity photos of Acquanetta wearing assorted Western costumes that were just lying around wardrobe. (I’ve seen them, and they’re insultingly stereotypical. All Acquanetta is missing is a butter dish.)

Acquanetta leaned into her new role with the aplomb of a seasoned actress.

I chose the Latin American background because it was exotic and fitted my type. But now that my little trick has been exposed, I see no reason to continue the deception or alibi. As a matter of fact, boys, I’m proud of being a full-blooded Indian.

There was an initial uproar about all this unnecessary deceit, but after a few months the furor died down. Of course, there were a still few problems with Acquanetta’s story as she told it:

- First, the town of Ozone, WY doesn’t seem to have ever existed. It’s possible it was just a small, unincorporated settlement, but it’s a little odd that there’s no records of it anywhere.

- Second, her birthdate seemed to vacillate between 1920 and 1921 depending on who she was telling the story to, and when.

- And finally, there is absolutely no way that “Burnu Acquanetta” is an actual Arapaho name. Just look at it! The Latin roots are right there.

In the end, though, it turned out that no one really cared all that much.

Walter Wanger’s Arabian Nights (1942) was released on Christmas Day, 1942. Turns out the harem girls aren’t in it all that much. When they are on the screen, though, Acquanetta is definitely the standout of the group, and even had a few lines at the beginning of the movie, pretending to have trouble reading from a book. In the end, though, she doesn’t make much of an impression.

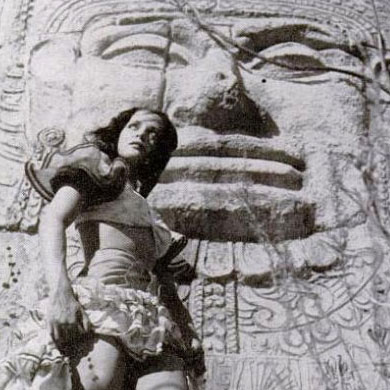

Later in the year she landed the supporting role in the musical comedy Rhythm of the Islands (1943), appearing opposite Allan Jones and Jane Frazee. This time, it was a credited role, that of “Luani,” though it was a role with next to no dialogue. Acquanetta definitely makes an impression on the screen, with her skimpy native costume showing as much skin as the censors of the time would allow. Her acting, though… To be fair, she was doing that broken English “native voice” that Hollywood used all the time back then, and it’s hard to sound good doing that.

A Human Form with Animal Instincts

It was clear that Universal had no idea what to do with Acquanetta. Her infamy hadn’t turned in to celebrity. She couldn’t act very well. She could dance, but she wasn’t exactly Cyd Charisse. She could swim, but you can only make so many aquamusicals and Esther Williams had the market cornered. She was very beautiful, but beautiful women in Hollywood are a dime a dozen.

So Universal did what they did with every actor they couldn’t figure out: they turned her over to the horror division. And the horror division did what they always did with an actor who couldn’t act: they put her in a role where she didn’t have to speak.

In Captive Wild Woman (1943) Acquanetta plays what is definitely the most unusual monster in the Universal Horror cannon: Paula Dupree, the Ape Woman. Paula may seem to be a dark and alluring beauty, but she is secretly a gorilla given the appearance of a beautiful woman through a strange combination of gland transplants and hypnosis. Unfortunately for everyone else in the movie, when Paula’s savage animal passions are inflamed, she reverts to her true form, complete with a Wolfman-style transformation sequence, and goes on a violent rampage.

Acquanetta as Paula is only on screen for about a third of the movie. Most of the time we see Paula’s original gorilla form, played by stuntman “Crash” Corrigan, whose primary qualification for the role was that he owned his own gorilla suit. That didn’t stop Acquanetta from claiming in her later years that wearing the gorilla suit made her faint from the heat, or that there was a real gorilla on set that chased her around.

Captive Wild Woman is a deeply disturbing movie. The New York Times bluntly declared: “The picture as a whole is in decidedly bad taste.” John Carradine’s lascivious mad scientist is distressingly open about his desire to create “a human form with animal instincts” that will be receptive to his depraved lust. For most of the movie, the only person of color is little more than a snarling jungle beast only able to express herself through violence. And that’s without getting into all the implied bestiality!

The film still managed to be a mild success for Universal, probably because its budget was so low. A sequel was rushed into production.

In the meantime, Acquanetta was cast in The Mummy’s Ghost (1943) as Amina Mansouri, the Mummy’s love interest. However, while filming a scene where Amina faints, she hit her head on some rocks. They were supposed to be papier-mâché rocks, but apparently the set decorators working that day had decided to save some time by whitewashing real rocks. Acquanetta was knocked out cold and remained unconscious for an entire day. While she recovered from her injuries, the production moved ahead, replacing her with Ramsay Ames.

At least, that’s the story that the studio released to the press. It seems just as likely that director Reginald Le Borg realized that Acquanetta just didn’t have the acting chops to carry the movie’s love story (such as it is) and replaced her with an actress who could. If so, it didn’t work out for Le Borg, because he was stuck with Acquanetta for his next few films.

She went back to the role of Paula Dupree once again for Jungle Woman (1944). After an introduction made of recycled footage that takes up the first third of the running time, Paula is briefly resurrected by a different mad scientist, falls in love with his future son-in-law, and once again goes on a violent rampage before being killed. This time she gets a few lines. The film would have been better off letting her be silent.

After that, it was on to the Inner Sanctum mystery Dead Man’s Eyes (1944), where she played a jealous model who blinds Lon Chaney Jr. It’s not a good movie, and Acquanetta is one of the worst parts of it. Her accent definitely has to be heard to be believed. It’s supposed to be… eastern European, I guess? But it’s all over the map. It’s so distracting you can’t even focus on her flat line readings.

After Dead Man’s Eyes, everyone at Universal realized that Acquanetta couldn’t act, and opportunities started to dry up. For her part, Acquanetta insisted she was being blackballed for refusing the unwanted attentions of Hollywood bigwigs like Darryl F. Zanuck and Clark Gable. Which would have been impressive since both men were away from Hollywood serving in the Army at the time.

On July 16, 1944 Universal quietly let Acquanetta’s contract expire rather than waste any more time and money developing her career.

Mildred from Norristown

Of course, what if her inability to act wasn’t the reason Acquanetta was fired? What if the reason she had been fired was because studio executives had found out that she was actually black?

In this version of the story, Acquanetta was born Mildred Davenport in Newberry, South Carolina. The Davenports eventually relocated to Norristown, Pennsylvania where they became one of the most well-off and socially prominent African-American families in the Philadelphia area.

Rather than being orphaned or running away to join a camp of gypsies or working as a waitress, Acquanetta just dropped out of the West Virginia State College for Negroes to pursue her dream of becoming a Broadway dancer. There weren’t a ton of roles for black dancers, and Acquanetta wasn’t light-skinned enough to pass for white, but maybe a Latin type?

After that, her story picks up right where we started this episode.

So instead of being a Native American posing as a Venezuelan, Acquanetta may have been an African-American posing as a Native American posing as a Venezuelan.

While Acquanetta may have been able to fool white America, she couldn’t fool black America. The African-American press had first taken notice of Mildred Davenport back when she was a Philadelphia socialite, and eagerly followed her career as she transformed herself into model/actress Burnu Acquanetta. And the papers weren’t coy about her origins, either! The Pittsburgh Courier called her “the pretty negro girl who took Hollywood by storm,” and the Los Angeles Sentinel referred to her as a “beautiful Negro screen actress”. Later in her career she would be profiled by Jet magazine on several occasions, though notably none of these publications were never able to interview her.

What stopped the story from getting out? Well, white people just didn’t read black papers. And that’s pretty much it.

Apparently, Acquanetta didn’t even bother to hide it all that much. On one occasion she took a white actress back to her family home in Norristown, and then had to pass her mother off as “the cook” rather than admit she was really black.

Eventually word got back to Universal, who panicked when they learned their new star was black. They’d already made several movies where Acquanetta had been the love interest for a white man. These interracial love scenes were somehow okay if she was Latin or Native American. But if it ever got out that she was black? White people in the South would lose their damn minds, and the resulting outcry could ruin the studio. Rather than take the risk, they let Acquanetta go.

For her part, Acquanetta adjusted her cover story to accommodate the few facts that dribbled out of the African-American papers into the public consciousness. It was a simple enough adjustment. She was still an Arapaho orphan, but instead being fostered by a white New England family she was taken in by the black Davenport family.

Of course, Acquanetta also couldn’t resist tinkering with the other parts of story, either, changing her father from a full-blooded Arapaho to being part-English, part-French, part-Jewish, and an illegitimate descendant of King Charles I of England. Sometimes her father had five or six wives all over the country, and sometimes the Davenports were somehow his in-laws. The inconsistencies had the net effect of making every part of her story seem unbelievable, which may have provided her some additional cover.

After being dropped by Universal, Acquanetta’s career stalled out. She made the papers for getting married to a young G.I. shipping out to the front, only to have the marriage annulled by his parents. She appeared as a pinup girl in the September 29th, 1944 issue of Yank magazine (that’s “The Army Weekly,” not some salacious porno mag). For a while she was pursued by Sam Katzman of Monogram Pictures, though nothing ever came of it because of her stubborn insistence that she was meant to be in A movies in spite of her Z level talent.

RKO did hire Acquanetta to play the villain in Tarzan and the Leopard Woman (1946), one of Johnny Weissmuller’s lesser outings, and while she looks great in a leopard-skin unitard she once again can’t act her way out of a wet paper bag.

Eventually she drifted down to Mexico. Later, she would claim to have been sent down by the Roosevelt administration to act as a goodwill ambassador, but there’s no proof of that. It’s possible she was trying to make a name for herself in the booming Mexican motion picture industry, or that she was just drawn to Mexico’s slightly more cosmopolitan attitudes towards race.

Mostly she spent most of her time flirting in clubs with Mexican playboys. Eventually, she landed one of them, jet-setting Russian millionaire Ludwig Baschuk. The two were married by a rabbi in Cuernavaca on March 7, 1946. About a year later they had a son, Sergio, and Acquanetta settled into a life as s a wife and mother.

It didn’t last long. In 1949 Baschuk deserted Acquanetta for reasons unknown, so she filed for divorce, seeking $2,500 a month in alimony. Acquanetta didn’t come off very sympathetically in the proceedings. She threatened her ex-husband by claiming she knew “big people” who could throw him in jail. Baschuk comes off even worse, claiming that the couple had never actually been married, just cohabiting.

Turns out Baschuk was right. Mexican courts could find no civil records of their marriage anywhere. Eventually the suit was thrown out for lack of evidence, though Acquanetta would later claim she had dismissed it voluntarily so Baschuk wouldn’t take Sergio back to Mexico.

It didn’t take long before Acquanetta married again, this time to septuagenarian illustrator Henry Clive, who she had been modeling for. It seems to have been a companionate marriage, intended to provide some stability for young Sergio.

Clive was far from a jet-setting millionaire, though, so Acquanetta returned to acting. She had little problem finding roles in C pictures, since as one admirer noted, “People never pay to see Acquanetta act. They pay to see her.” She landed a small role a jungle girl in Mystery Science Theater 3000 staple Lost Continent (1951), playing against Cesar Romero. She had small, unmemorable rolls in Callaway Went Thataway (1951) and The Sword of Monte Cristo (1951).

Then, tragedy. Five-year-old Sergio died of cancer in late 1952, plunging the actress into a deep depression. Her marriage to Clive felt apart, and they divorced. She even had to sue the Manhattan Life Insurance company to just to get a payout on Sergio’s life insurance, since they were denying her claims for failure to report pre-existing conditions.

She took one more acting role, a bit part in Take the High Ground! (1953). After that, she did whatever it took to make ends meet, model work, advertising, and even working as a disk jockey for Los Angeles radio station KPOL.

Mrs. Touchdown

Not too long after becoming a DJ, Acquanetta met and married Palm Springs businessman Jack Ross. She would later claim that they met while she was playing the role of “Shira, the Dragon Lady” in the TV series China Smith (1952-1955) which would have been quite a feat since Shira was actually portrayed by Myrna Dell.

A few years later, the couple opened a series of Lincoln/Mercury dealerships out in Phoenix, Arizona and moved out to Mesa to be closer to them.

To promote the dealerships, Jack adopted the outsize persona of “Mr. Touchdown” for his TV and radio commercials, and also tried to grab viewers’ attention by showing off his beautiful movie-star wife. It proved to be a successful gamble, and they sold quite a few cars. It probably helped that each car also came with a trunk full of free groceries.

Jack’s car dealerships also sponsored the Friday night late late movies, which Acquanetta would come out to introduce.

Soon, the couple were beloved local celebrities and fixtures of Phoenix’s social scene.

Jack expanded the business, and even unsuccessfully ran for governor of Arizona in 1970 and 1974.

Acquanetta settled comfortably into her life as a trophy wife. She gave birth to four boys, Lance, Tom, Jackie and Rex. She gave freely of her time and money to local hospitals, theaters, museums and youth groups.

And, of course, like every rich person who moves to the southwest, she became a crazy New Age wacko. She kept her hair in long braids, dressed in flowing white kaftans, and accessorized with chunky turquoise jewelry. She became a teetotaler and a vegetarian. She developed psychic powers and the ability to see the future, or so she claimed. She self-published a book, The Audible Silence, filled with her banal poetry and philosophy. And she spent years refining her own tortured, obviously fake history.

Their car commercials became weird, with a white-clad Acquanetta spouting vague inanities like a “sexy Socrates” before Jack came on to give the hard sell. They also started giving out little porcelain Acquanetta dolls to car buyers.

If anything, the kitschy weirdness just brought Acquanetta a new generation of fans.

Unfortunately, Jack and Acquanetta’s marriage wasn’t perfect. Once, after catching Jack cheating, she reportedly rolled down the windows of his Lincoln Continental and filled it with wet cement. After a few more incidents like that, the couple divorced in the late 1980s. The big winner in their divorce? The city of Mesa, to whom she donated the Hohokam ruins at Mesa Grande.

Acquanetta even returned to acting one last time, taking a small role in the direct-to-video release Grizzly Adams: The Legend Never Dies (1989). For the most part, though she spent her later years in quiet reflection, happy to be a mother and a grandmother.

She passed away on August 16, 2004 and is buried in the Paradise Memorial Gardens in Scottdale. Today she is little remembered, except by long-term residents of Phoenix and fans of classic horror movies.

The Legend Never Dies

Looking back on the tale I’ve just told, I’m struck by two questions. First, what’s the truth? And second, why do I care?

As for the truth, there’s only one thing I can say for sure: she definitely wasn’t Venezuelan. But was she a black woman trying to pass as a Native American, or was she actually a Native American or biracial orphan taken in by a black family?

You can’t trust anything Acquanetta had to say about the matter. She was a product of the Hollywood studio system and as a result she was always shoveling piles of manure around burnish her own image. Most of her friends said she was warm and loving but always “on” and it was hard to know her true thoughts. Acquanetta always insisted she was a “kaleidoscope with many facets” and that may be where we have to leave it.

There’s no way to know for sure other than DNA testing the heck out of the Ross and Davenport families. What good what that do, though? In the end, it’s their family business, and we should just butt out. (And yes, I realize that’s an odd stance to take for someone who’s spent the last twenty minutes airing Acquanetta’s dirty laundry.)

As for why I care? I think I’m less interested in Acquanetta herself and more what her story says about this country and its people.

One of the stories we tell ourselves as a nation is that America is a place where you can leave the past behind and become whatever you want to be. That freedom, though is really only for white Americans, and denied to everyone else because of the color of their skin and the racism of the white majority.

I can’t blame someone who was clearly the victim of both personal and systemic racism from doing everything they could to bypass the system by passing as a more “acceptable” ethnic group. And the idea that there’s even such a thing as a more acceptable ethnic group… Don’t get me started. And the concept of “passing” itself is also inherently problematic, because it is arguably a selfish act in which the individual aligns themselves with the oppressor for personal gain without doing anything to benefit the oppressed.

Then again as middle-aged middle-class cis white man I am probably the worst person to be talking about all of this. (I believe technically I qualify as “part of the problem.”) Others have spoken about these issues with more insight and eloquence than I could ever manage.

So maybe that’s why I’m interested in Acquanetta’s story. Because it shows you the seams, the cracks, something that lets you work your way something bigger than the story itself.

Connections

Universal may have let Acquanetta’s contract expire in 1944, but they went on to make one more Ape Woman film without her — 1945’s Jungle Captive, featuring Vicky Lane as Paula. Jungle Captive is a terrible movie, but it’s notable notable for being Universal’s first attempt to make a horror icon out of acromegalic actor Rondo Hatton. We recounted Rondo’s life story back in Series 1’s “Monster without a Mask.”

Sources

- Mallory, Michael. Universal Studios Monsters: A Legacy of Horror. New York: Universe Publishing, 2009.

- Mank, Gregory William. Women in Horror Films: 1940s. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1999.

- Weaver, Tom, et al. Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films, 1931-1946 (Second Edition). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2007.

- “An ancient treasure in modern Mesa.” Arizona Museum of Natural History. https://www.arizonamuseumofnaturalhistory.org/plan-a-visit/mesa-grande/an-ancient-treasure-in-modern-mesa Accessed 12/29/2020.

- “Thrilled in thirteenth.” Pittsburgh Courier, 28 Jun 1941.

- “Latins ‘gift to films’ just U.S. Indian Girl.” Miami News, 20 Jul 1942.

- Harrison, Paul. “Brownskin movie cutie No. 1 Hollywood puzzle.” Ventura County (CA) Star-Press, 31 Jul 1942.

- Schallert, Edwin. “Deceptive Burnu gets important film ‘break.'” Los Angeles Times, 10 Aug 1942.

- “Venezuelan Volcano: Fiery Burnu Acquanetta flares up in harem.” LIFE, 24 Aug 1942. https://books.google.com/books?id=fk4EAAAAMBAJ Accessed 12/20/2020.

- Robb, Inez. “Lovely fakers who got away with it.” American Weekly, 27 Sep 1942.

- “Speaking of Pictures…” LIFE 26 Oct 1942. https://books.google.com/books?id=UEEEAAAAMBAJ Accessed 12/20/2020.

- “‘Horror Queen’ of screen hurt.” Los Angeles Times, 27 Aug 1943.

- “Actress loses alimony plea.” San Bernadino County (CA) Sun, 13 Jan 1950.

- “Acquanetta loses right to obtain part of fortune.” Pittsburgh Courier, 21 Jan 1950

- “Hollywood jungle girl.” Jet, 14 Feb 1952. https://books.google.gm/books?id=XI8DAAAAMBAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=acquanetta&f=false Accessed 12/20/2020.

- “To bury son of actress.” Hazelton (PA) Plain-Speaker, 4 Nov 1952.

- “Insurers sue film actress in son’s death.” Los Angeles Times, 14 Mar 1953.

- “Miracle of Roses pageant Saturday a family tradition.” Arizona Republic, 6 Dec 1967.

- Wilson, Maggie. “The private side of a public personality.” Arizona Republic, 5 Oct 1969.

- Smith, Turk. “Selling that ‘dream car.'” Arizona Republic, 12 Oct 1969.

- Overend, William. “The philosopher, the cowboke, and the leopard woman.” Arizona Republic, 17 Jun 1973.

- Tabor, Gail. “Acquanetta portrait returned after years.” Arizona Republic, 1 May 1992.

- Cieslak, David J. “’40s actress Acquanetta dies at 83.” Arizona Republic, 17 Aug 2004.

- Pela, Robert L. “Acqua Blues.” Phoenix New Times, 2 Sep 2004. https://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/arts/acqua-blues-6427534 Accessed 12/20/2020.

- Pela, Robert L. “The many mysteries of Acquanetta (and Jack Ross).” Phoenix New Times, 25 Sep 2014. https://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/best-of/2014/megalopolitan-life/best-of-phoenix-2014-legend-city-the-many-mysteries-of-acquanetta-and-jack-ross-7296643 Accessed 12/20/2020.

- “Horace Davenport, groundbreaking Montgomery County senior judge, dies at 98″.” Pottstown (PA) Mercury, 5 Apr 2017. https://www.pottsmerc.com/news/horace-davenport-groundbreaking-montgomery-county-senior-judge-dies-at-98/article_95c904bf-4566-55c7-a229-9825aab84c70.html Accessed 7/27/2021.

- Halliburton, Karen. “Who was 40’s B-actress Acquanetta and was she trying to pass?” 50Bold, Aug 2019. https://50bold.com/who-was-40s-b-actress-acquanetta-and-was-she-trying-to-pass/ Accessed 12/29/2020.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: