Dawson’s Creek

the curious story of Piltdown Man

On February 15th, 1912 Arthur Smith Woodward received a letter from his good friend Charles Dawson.

Smith Woodward was one of the most pre-eminent paleontologists in Great Britain, Keeper of Geology at the British Museum, and Fellow of the Royal Society. Dawson was a solicitor from Hastings. In his youth Dawson had been an avid fossil hunter with keen eye for easily-overlooked details, and as he grew older he developed an interests in archaeology, paleontology, and geology which brought him into contact with Smith Woodward. The two men soon developed a profitable personal and professional relationship, with Dawson funneling the fossils he found to Smith Woodward, whose analyses won them both fame and fortune.

(Well, mostly fame. If you want to get rich quick, you might want to go into a field other than paleontology.)

At first Dawson’s letter seemed like one of his usual rambling missives. He went on for a while about the book Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was writing, The Lost World, which sounded interesting. He dropped a discreet reminder about some money Smith Woodward owed him. Then he dropped a huge bomb:

I have come across a very old Pleistocene bed overlying the Hastings Bed between Uckfield and Crowborough which I think is going to be interesting. It has a lot of iron-stained flint in it, so I suppose it is the oldest known flint gravel in the Weald. I (think) portion of a human skull which will rival H. heidelbergensis [sic] in solidity.

Now that got Smith Woodward’s attention.

Fossils of pre-human hominids had first been found in Germany’s Neander Valley in the 1850s and now the remains of so-called “Neanderthal man” were being found all over Europe. An even older skeleton, the so-called “Java Man,” had been unearthed in the Dutch East Indies in 1891. These discoveries were forcing scientists to rewrite everything they thought they knew about human prehistory and evolution.

Scientists everywhere but England, that is. Oh, sure, there were plenty of bones being dug up, but they were all Cro-Magnon. Old, to be sure, but still modern humans when you got right down to it. Where were the English pre- and proto-humans, the ancestral progenitors of British greatness?

Apparently, in a gravel bed in the wealden somewhere between Uckfield and Crowborough.

Professional commitments kept Smith Woodward and Dawson apart until late May, but when they finally managed to get together Dawson had quite a tale to tell.

Several years ago he had been at Barkham Manor, near Piltdown Common in Fletching, East Sussex. He had a gentleman’s agreement with the lord of the manor allowing him to wander around and collect fossils, as long as he didn’t make a mess. On this occasion he came across a group of laborers digging in a gravel pit. He asked them if they had seen anything unusual, and the foreman handed him a shard of a fossilized skull they had accidentally smashed, thinking it was a coconut. (Apparently a common sight in the gravel pits of East Sussex.) Dawson pocketed the skull fragment and politely asked the workers to let him know if they found anything else.

The solicitor had returned to the gravel pit over the years, slowly accumulating more skull fragments and a few fossilized teeth. He recognized the teeth as belonging to a species of hippopotamus that had died out during the Pleistocene epoch. That got him thinking — perhaps the skull was from the Pleistocene, too. What did Smith Woodward think?

Smith Woodward thought it almost seemed too good to be true. Here, at last, was what everyone had been searching for: the great British hominid.

In the summer of 1912, Smith Woodward, Dawson, and a handful of trusted associates returned to Barkham Manor to see what else they could find. One of Dawson’s fossil-hunting friends, French paleontologist and seminary student Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, dropped by every now and then to assist. Local photographer John Frisby was on hand to document anything interesting that turned up. There was Smith Woodward’s assistant, Frank Barlow. And let’s not forget the dig’s mascot, Chipper the goose, whose hilarious antics kept their spirits light.

For several months they plumbed the depths of the gravel pit, looking to unearth its secrets. Mostly they found prehistoric mammal bones and teeth, but they did find seven more fragments of the cranium along with the right half of a jaw with two molars still attached. They also found flint tools, a sure sign of human or proto-human activity.

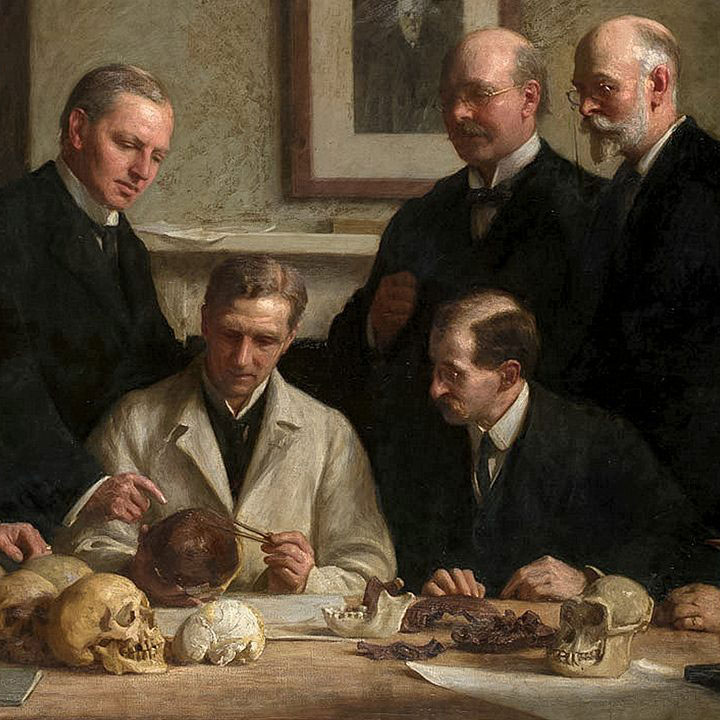

At the December 18th, 1912 meeting of the Geological Society of London, Smith Woodward revealed what he and Dawson had discovered. They had found ten large pieces of the skull representing almost the entire parietal bone along with part of the nasal bone and and orbital ridge, and the right third of the mandible. The bones were remarkably thick, suggesting they came from a primitive man, and chemical tests revealed that they had completely fossilized. Their age was estimated at about half a million years.

Smith Woodward also revealed his reconstruction of the complete skull. With large portions still missing, much had to be inferred from the few fragments they did have. One significant issue was that the articular condyle — the little ball where the mandible bumps up against the temporal bone — had snapped off, which was problematic as hominids and apes had very different structures there. However, the two molars still attached to the mandible had wear patterns suggesting the attachment had been quite man-like, so that is what Smith Woodward went with. He also gave it a prominent human-like forehead, albeit a very low one.

Smith Woodward felt the skull’s distinctive attributes made it the hitherto “missing link” between man and ape, an ancestor with the large brain of modern man but with a large jaw and other ape-like features. He gave this new hominid the grandiose name of Eoanthropus dawsoni, or “Dawson’s dawn ape.”

Everyone else just called it “Piltdown Man.”

Many hailed Smith Woodward’s discovery as a breakthrough: the earliest man, and he was British! But there were doubters from the start. Objections tended to break down along three lines.

First, how old was Piltdown Man, really? The fossil dating techniques of the time involved estimating the age of the strata they were found in, but a gravel pit was just a jumble of loose rock from many different strata. Piltdown Man could have been 500,000 years old, but he could have also been much younger than that.

Smith Woodward and Dawson conceded that they were basing their age on a chemical analysis of the bones, combined with some inferences drawn from the fossilized fauna found alongside them.

Second, were all of the bone fragments from the same individual? The pieces of the parietal bone clearly fit together, but did they come from the same skull as disconnected pieces like the nasal ridge and the orbital bone? And the mandible looked distressingly similar to that of a modern orangutan. These could have been the mixed up remains of several different individuals, or even several different hominids, or even several different hominids and a primate.

Smith Woodward and Dawson stressed that the bone fragments were found in such close proximity to each other that they could have only come from the same individual.

And finally, how accurate was the reconstruction of the skull? A group of the country’s most pre-eminent geologists, paleontologists and anthropologists, including William Boyd Dawkins, Grafton Elliot Smith, and Arthur Keith, thought that Smith Woodward had bungled the job.

Keith was the most vocal about his objections. Smith Woodward had consulted him during the reconstruction process, and even then Keith thought his colleague was going about it all wrong. The cranium was clearly too small, and the lower part of the skull was all wrong. A jaw that ape-like attached to a skull that man-like would make it virtually impossible for its owner to breathe or swallow. An ape-like jaw with limited lateral movement it would be unlikely to produce the human-like flattening of the rear molars. Keith resolved these issues by making his own cranium, less an ape with a modern cranium and more like a man with a big old jaw — sort of a prehistoric Robert Z’dar.

On August 11th, 1913 Keith and Smith Woodward had a public debate about the reconstruction. To most observers, Keith was the clear winner. His expertise with hominid and primate ancestry made him far more convincing than Smith Woodward, whose specialty, after all, was prehistoric fish. Even so, there was no way to tell which of the two was correct unless they found another piece of Piltdown Man’s skull that provided more information about the shape of the skull — something like the missing articular condyle, or his canine teeth.

Nine days after the debate, Teilhard de Chardin found one of Piltdown Man’s missing canines. It projected forward, like an ape’s, suggesting Smith Woodward’s reconstruction had been right all along. Keith swallowed his pride and admitted defeat.

Over the next several years Smith Woodward and Dawson continued to plumb the depths of the gravel pit at Barkham Manor. The rest of Piltdown Man’s remains eluded them, though they did unearth evidence of complex tool-making, including a large club carved from an elephant’s thighbone. Each new find literally rewrote the timeline of early human history.

Then on August 10th, 1916 Charles Dawson died unexpectedly from a case of blood poisoning caused by his chronic periodontitis. (People, go see your dentist.) At his funeral service he was remembered as “The Wizard of Sussex,” one of the last and greatest of Britain’s gentleman scientists.

Several months later, Smith Woodward sadly revealed his friend’s final discovery: more hominid skull fragments and teeth from somewhere near Sheffield Park, that appeared to be from the same species as Piltdown Man. Dawson had found these “Piltdown II” fragments in 1915, but his illness had prevented him from leading Smith Woodward to the site.

After Dawson’s death, Smith Woodward spent many months searching for the Piltdown II but was unable to locate it. Further excavations of the original Barkham Manor site also proved fruitless. There was nothing more to find, it seemed.

That was all right. Important discoveries had been made. The earliest man. The earliest Englishman. Proof, at last, that man had first evolved big brains and then rose up on his own two feet.

Fraud Glorious Fraud

Still, not everyone was on board. Non-British paleontologists continued to find some of the nationalistic claims about Piltdown a bit much. Others still maintained that the skull and jaw didn’t go together.

It didn’t help that no one was finding anything like Piltdown Man anywhere else. In the 1920s, better-documented and verified discoveries like Peking Man in China and the Taung Child in South Africa created a narrative that was exactly the opposite of “brains before bipedalism.” They seemed to suggest that hominids first rose up on two legs, then developed smaller jaws, and then larger craniums. More discoveries in the 1930s and 1940s seemed to cement the idea. Piltdown Man began to look less like the missing link between human and ape and more like a weird mutant atavism or dead-end evolutionary offshoot.

A growing chorus of paleontologists and anthropologists began to clamor for the remains to be tested so they could see just what the heck was going on. That was never going to happen while Sir Arthur Smith Woodward was alive. He guarded the remains like a jealous lover. He had his reasons. First, most of the tests being proposed were inherently destructive and he didn’t see the point of ruining a perfectly good fossil for the sake of a potentially inconclusive test. And second, well, his good name and reputation depended on those remains being authentic and he wasn’t going to give his knighthood up without a fight.

Of course, you can’t live forever, and Smith Woodward passed in 1944. Several years later in 1949 the British Museum finally allowed the Piltdown remains to be tested. The honors went to Dr. Kenneth Oakley, a paleontologist who had been refining the technique of fluorine dating.

The basic idea behind fluorine dating is that fluorine continues to bind to the calcium in bones after death, so by testing the amount of fluorine in a fossil you can get a general idea of how old it is, with more fluorine indicating a greater age. It’s not a perfect technique — environmental variations in the amount of fluorine make it useless for establishing an absolute chronology, but it can be useful for establishing the relative age of fossils from the same area, and confirming whether two bones come from the same individual.

Oakley tested the Piltdown fragments, as well as some of the fossilized animal remains recovered from Barkham Manor and other nearby sites. The results were… well, not entirely unexpected if you’ve been following along. The Piltdown remains were far younger than the animal remains. Instead of being 500,000 years old, they were only about 100,000 years old. It suggested that Piltdown Man was not the missing link after all, but a one-off teratism.

Oakley also uncovered something shocking while going through Smith Woodward’s stuff: a third set of hominid remains discovered by Dawson near Barcombe Mills (now referred to as Piltdown III even though the find comes before Piltdown II in the chronology). For some reason, Smith Woodward had never investigated these remains further and hidden them away in his office.

In 1953 word of Oakley’s tests and the existence of Piltdown III remains reached S. Joseph Weiner, a professor of anthropology at Oxford. When he heard them, he was struck by the realization that Piltdown II and III had never been investigated in any meaningful way, and frankly, neither had Piltdown I. Weiner put together a team consisting of himself, Oakley, and fellow anthropologist Wilfred le Gros Clark to get to the bottom of Piltdown once and for all.

It turns out the doubters were right.

The skull fragments and the mandible did not belong together. Refinements to Oakley’s dating technique established that the cranium was only about 12,000 years old and the mandible was far younger. For that matter, the mandible and teeth didn’t go together, either. The teeth had also been filed and shaped to change their wear patterns.

Thanks to these discrepancies, the trio were allowed to conduct some more destructive tests. Drilling into the fossils they discovered that the teeth had been painted to make them look older, with what appeared to be commercially available Van Dyck brown paint. The skull fragments also showed signs of being chemically stained, most notably, the presence of chromium.

The skull was probably that of a recent Cro-Magnon. The mandible seemed to belong from a modern orangutan. And the teeth were from a chimpanzee. The Piltdown II and III skull fragments, at least, seemed to be of a similar age to the Piltdown I skull fragments. Or rather, the exact same age as the Piltdown I skull fragments. Turns out, they were all from the same skull.

The conclusion was inescapable. Piltdown Man was a hoax.

The obvious next question is: who was the hoaxer?

Whodunnit?

The unfortunate answer is that we don’t know, and will probably never know.

Forty years had gone by and everyone directly involved in the discover had either died or was old and in ill-health. There was no tell-tale forensic evidence pointing at a particular suspect, no secret revelations hidden in long-forgotten diaries diaries, no preponderance of circumstantial evidence.

That won’t stop us from putting on our rumpled overcoat, gumming a half-smoked stogie and taking a look at some of the leading suspects.

The Writer

Let’s start with the most famous name associated with the hoax: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Did Conan Doyle have the means? Absolutely. He had been trained as a physician and was widely read on scientific subjects, including paleontology and evolution. In 1912 he was just putting the finishing touches on The Lost World, a novel about a hidden plateau populated by dinosaurs and cavemen, and as part of his research he’d studied how to fake fossils. One of the characters in the novel, Tarp Henry, even makes the claim, “If you are clever and know your business you can fake a bone as easily as you can a photograph.”

Did he have the opportunity? Sure. He had ample resources to acquire human and exotic animal remains. He was a distant acquaintance of Charles Dawson, and could have figured out the areas where the solicitor rambled. And he lived in Crowborough, only a few miles from Piltdown.

Did he heave the motive? Almost certainly not. Conan Doyle was scrupulously moral (a bit of a scold, if we’re being honest), and the hoax didn’t benefit him in any way. He had no reason to want to embarrass Charles Dawson or Arthur Smith Woodward. If the hoax was intended as guerrilla marketing for The Lost World, it’s hard to see how, or why he thought it would be more effective than a cover blurb proclaiming “from the creator of Sherlock Holmes.”

Others have suggested that Conan Doyle was seeking revenge on modern science for constantly dunking on his beloved Spiritualism. That’s quite a stretch, and also premature — his beef with science didn’t really get started until a few years later when he was taken in by the transparently fraudulent Cottingley Fairies. (Turns out Tarp Henry was right: you can fake photographs pretty easily.)

Besides, if you’re trying to discredit a whole field of science with a carefully crafted hoax… then you kind of have to reveal the hoax at some point? So why didn’t Conan Doyle do it? Those who think he’s the guilty party can’t come up with a better explanation than, “he was very busy and just forgot,” which isn’t going to cut the mustard.

The Revenge Squad

That sort of revenge, though, is often put forth as the driving force behind the Piltdown hoax.

Maybe it was elaborate trap intended to embarrass Arthur Smith Woodward, engineered by one of his rivals like geologist William Johnson Sollas.

Maybe the trap was meant for Charles Dawson and was engineered by one of his rivals: fellow fossil hunter William James Lewis Abbott, who was jealous of his fame; Hastings museum curator William Ruskin Butterfield, who was angry that Dawson took all his best finds to London; or the entire Sussex Archaeological Society, who he had screwed in a real estate deal. (Boy, Dawson sure had a lot of enemies for a country simple solicitor, didn’t he?)

Maybe the hoaxer had an even bigger target in mind. Samuel Allison Woodhead’s goal is supposed to have been nothing less than discrediting the entire theory of evolution.

These all run into the same problem as the Conan Doyle theory, in that none of the supposed hoaxers ever actually tried to spring the trap once their quarry had been lured into it. Revenge may be a dish best served cold but it’s also best enjoyed while all the parties involved are still alive. There’s just no record of these folks speaking out, or speaking out and being ignored.

The Practical Joker

There’s only one revenge-motivated suspect who deserves further scrutiny: Martin Hinton, one of Smith Woodward’s former students, a fellow employee of the British Museum, and later Keeper of Zoology.

In Hinton’s case, there’s some circumstantial evidence that points to his involvement. Years after his death, one of his trunks was found to contain fake fossils similar to the Piltdown remains, along with all of the tools and chemicals necessary to fake them. He’s also a dead ringer for a mysterious stranger once spotted lurking around the Barkham Manor dig site.

Hinton never said a word about Piltdown Man in public, but was known to have expressed his doubts in private. That does not mean that he was in on it, though. It seems more likely that he suspected the hoax but couldn’t actually prove it, and decided to keep his mouth shut rather than risk angering a colleague and getting swept up in vicious academic politics.

If he was in fact the mysterious stranger, it should be noted that the stranger was spotted at Barkham Manor shortly before the discovery of the dig’s most controversial artifact. I have previously described it as a “large club carved from an elephant’s thighbone,” but in the club is actually a dead ringer for a cricket bat. As tools go, that’s a bit on the nose for “the Earliest Englishman” but it fits in perfectly with Hinton’s offbeat sense of humor. Maybe he planted the cricket bat as a warning to the real hoaxer, or as a test to see just how credulous Smith Woodward and Dawson were.

In the end, the trunk is the only real evidence tying Hinton to Piltdown, and it’s just not enough to make the case that he was the hoaxer. Yes, the contents of the trunk could be used to fake fossils, but they also had perfectly legitimate uses and there’s no evidence Hinton ever tried to pass off fake fossils as real ones.

The Self-Starters

It’s clear revenge couldn’t have been the hoaxer’s true goal. It seems far more likely that the hoaxer intended to use the hoax to further their own career.

Two of the names often considered here are Grafton Elliot Smith and Arthur Keith. They had been involved in the acrimonious public debate over Smith Woodward’s reconstruction of the skull. They lost that debate, though, which would seem to eliminate them as suspects. The thought seems to be that they were outfoxed by a second hoaxer, and kept mum so that their own involvement wouldn’t be discovered.

This theory has one major flaw: If Elliot Smith or Keith intended to use Piltdown Man to further their own careers, then why involve Smith Woodward and Dawson? It would have been far easier the for hoaxer to just cut them out of the picture and grab all the glory for themselves.

The Seminarian

That train of thought suggests that the hoaxer did grab all the glory, or at least part of it. That points us in the direction of those who were directly involved in the discovery.

How about Pierre Teilhard de Chardin? He was present for most, if not all, of the Barkham Manor finds and had been the one who uncovered Piltdown Man’s missing canine tooth at just the right time. That’s awfully suspicious. He also wrote letters implying he had seen the Piltdown II remains in situ, but they were discovered while he was serving in the French Army during World War I which seems to imply he had been involved in forging and burying the fossils.

On the other hand, Teilhard de Chardin was hardly a Piltdown Man diehard like Smith Woodward and Dawson. He had written papers expressing his doubts as early as 1920, though he kept his criticism mild out of respect for his dead friend and esteemed colleagues. In 1921 he was involved in the discovery of Peking Man, one of the first big chinks in Piltdown’s armor.

Those letters? They were written forty years after the fact, and the inconsistencies seem less like the tell-tale slip-ups of a congenital liar and more like the mental lapses of a very old man. If you read them closely he doesn’t actually claim to have seen the remains, only the field where Dawson found them, and he seems to have mixed up Piltdown II and Piltdown III.

Teilhard de Chardin seems to have been singled out for extra scrutiny simply because he was the easiest person on the dig to other. The British suspected him because he was French. Protestants suspected him because he was Catholic. Atheists suspected him because of his attempts to reconcile evolution theory with theology. Professional scientists suspected him because he was a dilettante.

In the end, though, he just turns out to have been a guileless young man who aged into a guileless old man with a bad memory.

The Geologist

How about Arthur Smith Woodward? If there was anyone who benefited from the hoax, it was him. The discovery of Piltdown Man brought him fame, fortune, high honors, and a knighthood. He also engaged in some suspicious behavior, covering up the Piltdown II finds and blocking forensic testing of the other Piltdown remains.

But ask yourself this: if Smith Woodward really was the hoaxer, why did he spend years fruitlessly searching Piltdown, Sheffield Park and Barcombe Mills for remains that never materialized? It can’t all be part of the cover-up.

Most of Smith Woodward’s colleagues considered his personal integrity was above reproach and felt he was an innocent dupe. On the other hand, his actions later in life suggest he had some doubts about the authenticity of the Piltdown finds, and that rather than bring them to light he covered them up in order to preserve his reputation.

Smith Woodward may have not been the perpetrator of the hoax, but he was definitely a perpetuator of the hoax. Dupe? Yes. Innocent? Probably not.

The Country Solicitor

How about Charles Dawson?

Well, for years the opinion was that the expertise required to fake a fossil was far beyond the reach of a simple country solicitor. Still, it’s a little suspicious that Dawson was extremely vague about the circumstances surrounding the initial Piltdown finds. And that he was the only person present for every one major find. And that according witnesses he seemed to be subtly steering workers towards the areas where discoveries were subsequently made. And that no new fossils were found after his death. Perhaps he was in league with the true hoaxer?

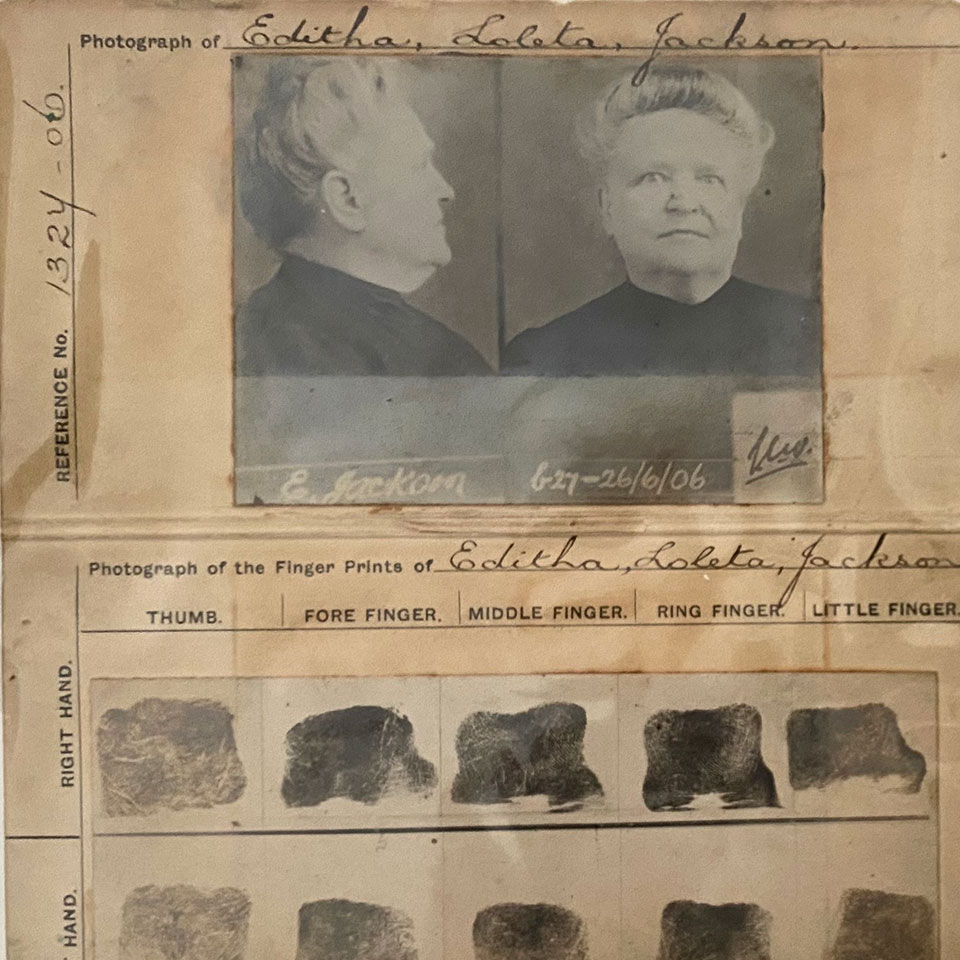

What if I told you that on at least two occasions he was caught chemically treating and staining bones in his law office? It’s true. The accusations came from locals who had axes to grind with Dawson, so they have to be taken with a grain of salt.

What if I told you that in 2003, Miles Russell review of Dawson’s career as an antiquarian and paleontologist turned up almost four dozen obvious frauds? The highlights include:

- a Neolithic stone axe, which conveniently crumbled to dust before anyone else could see it;

- a weird prehistoric rowboat found buried on the beach in Bexhill, which again conveniently disintegrated before it could be shown to anyone else;

- a strange transitional form of horseshoe, half nailed-on and half tied-on, that would have been utterly useless;

- a Roman cast-iron statue rescued from a cinder heap, which turned out to be made through techniques not known to the Romans;

- Roman-era bricks and building materials that were only revealed to be frauds by modern chemical analyses;

- a forged bronze seal from Hastings castle;

- and any number of doctored fossils including stained bones and filed teeth.

Those are just the obvious frauds! There are dozens of other artifacts that seem to be legitimate but whose provenance is sketchy at best. At this point you’d have to start thinking that Charles Dawson was the most credulous individual in the world, or that he was the hoaxer.

(And let’s be honest if you’re willing to entertain the idea that a dilettante like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was capable of faking the fossils, you have to concede that the same techniques are easily within the reach of an enthusiastic hobbyist.)

The circumstantial evidence connecting suspects like Martin Hinton to the case is weak at best. But the circumstantial evidence connecting Charles Dawson to the case is almost overwhelming. It is not a stretch to say that he is the only person who can absolutely positively 100% be directly connected to the fraud. Dawson seemed to have two real motives: improving his social standing by winning a knighthood and admission to the Royal Society, and recapturing his youthful glory days when he was the fossil-finding wonder boy of Sussex.

He probably would have gotten away with it, too, if it weren’t for his untimely death. Ironically, death is what ultimately put him above suspicion — it stopped Dawson before he could overextend himself and slip up, and shielded his memory with the very British urge to not speak ill of the dead.

The Goose

So, definitely Dawson, then. The only question we can’t answer is if he had an accomplice.

If he did have an accomplice, who could it have possibly been? It doesn’t seem to have been Smith Woodward, or Hinton, Teilhard de Chardin. What if those other suspects are mere red herrings, meant to distract us from the real mastermind…

Chipper the Goose.

Everyone knows that geese are @$$holes. It would be just like a goose to fake a series of Pleistocene fossils, bury them in a gravel pit, hide the rake, and then lock me in a telephone booth and make me soil my pants. That’s just classic goose.

All Joking Aside

All joking aside, it was astounding how quickly Piltdown Man was removed from science books once the hoax was revealed. Only a few diehards continued to insist that Piltdown was authentic, and their objections seemed less like scientific ones and more like attempts to salvage the diminished reputations of Smith Woodward and Dawson. In 1959 a third round of tests established that it the skull was, in fact, no more than 500 years old and even the diehards had to give up.

Today Piltdown Man is a cautionary tale, a warning to scientists about the dangers of deferring to authority and a reminder that if something seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Connections

Piltdown Man is written up in our holy text, Strange Stories, Amazing Facts in the article “The Ancestress of Man” (p. 474). (“Strange Stories, Amazing Facts”).

The discovery that fluorine continues to accumulate in fossilized bone was made by Swedish chemist Jöns Jacob Berzelius. You may remember Berzelius from his brief appearance in “Westward Huss,” when he revealed that a so-called runic inscription was nothing more than naturally occurring cracks in a rock.

Arthur Keith, who debated Arthur Smith Woodward about the proper way to reconstruct Piltdown Man’s skull, also makes a brief appearance in “Lost Legacy” where he authenticates cultural artifacts looted from Belize by adventurer Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges.

Arthur Conan Doyle also appears the tale of the Blue-Eyed Six (“Make Insurance Double Sure”), which supposedly inspired him to create Sherlock Holmes’s “Red-Headed League.”

There must have been something in the water there in Sussex; fellow resident Harry Price (“The Fakiest Fake in England”) had a bad habit of unearthing “artifacts” that he himself had faked, before eventually deciding to become a paranormal investigator instead.

Sources

- Booher, Harold R. “Science Fraud at Piltdown: The Amateur and the Priest.” Antioch Review, Volume 44, Number 4 (Autumn 1986).

- Falk, Dean. The Fossil Chronicles: How Two Controversial Discoveries Changed Our View of Human Evolution. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2011.

- Feder, Kenneth L. “Piltdown, Paradigms and the Paranormal.” Skeptical Inquirer, Volume 14, Number 4 (Summer 1990).

- Glassman, Gary. NOVA: The Boldest Hoax. 2005.

- Goodrum, Matthew and Olson, Cora. “The Quest for an Absolute Chronology in Human Prehistory: Anthropologists, Chemists, and the Fluorine Dating Method in Palaeoanthropology.” British Journal for the History of Science, Volume 42, Number 1 (March 2009).

- Goodwin, A.J.H. “The Curious Story of the Piltdown Fragments.” South African Archaeological Bulletin, Volume 8, Number 32 (December 1953).

- Haddon, A.C. “Eanthropus Dawsoni.” Science, Volume 37, Number 942 (January 17, 1913).

- Langdon, John H. “Misinterpreting Piltdown.” Current Anthropology, Volume 32, Number 5 (December 1991).

- MacCurdy, George Grant. “Ancestor Hunting: The Significance of the Piltdown Skull.” American Anthropologist, Volume 15, Number 2 (April-June 1913).

- MacCurdy, George Grant. “The Revision of Eanthropus Dawsoni.” Science, Volume 43, Number 1103 (February 18, 1916).

- Manias, Chris. “Sinanthropus in Britain.” British Journal for the History of Science, Volume 48, Number 2 (June 2015).

- Nisbet, Matthew C. “The Piltdown Hoax Revisited: History’s Most Famous Science Fraud.” Skeptical Inquirer, Volume 45, Number 6 (November/December 2021).

- Pigliucci, Massimo. “Piltdown and How Science Really Works.” Skeptical Inquirer, Volume 29, Number 1 (January/February 2005).

- Pyne, Lydia. Seven Skeletons The Evolution of the World’s Most Famous Human Fossils. New York: Viking, 2016.

- Russell, Miles. Piltdown Man: The Secret Life of Charles Dawson and the World’s Greatest Archaeological Hoax. Stroud, UK: Tempus, 2003.

- Tobias, Philip V. “Piltdown: An Appraisal of the Case against Sir Arthur Keith.” Current Anthropology, Volume 33, Number 3 (June 1992).

- Weiner, J.S. The Piltdown Forgery. London: Oxford University Press, 1955.

- Walsh, John Evangelist. Unraveling Piltdown: The Science Fraud of the Century and Its Solution. New York: Random House, 1996.

Woodward, Sir Arthur Smith. The Earliest Englishman. London: C.C. Watts & Co., 1948.

Wyatt, Valerie and Roderick, Stacey (ed). Hoaxed! Fakes & Mistakes in the World of Science. Tonawanda: Kids Can Press, 2009.

Strange Stories, Amazing Facts. Pleasantville, NY: Reader’s Digest Association, 1976.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: