Nuns on the Run

miss bunkley's book

This is part three of a three-part series about escaped nuns and anti-Catholicism in early Nineteenth Century America. You don’t have to read the entire series to understand each individual story, but it would provide extra context that might be helpful. Part one, about nativists destroying a Boston convent in 1834, can be found here. Part two, about Protestant activists who claimed that convents were vice dens in 1836, can be found here.

In the previous two parts of this series, we discussed how European immigration to the United States sparked a backlash of nativism and anti-Catholicism in the 1830s. In general, this manifested as a widespread belief in anti-Catholic propaganda (like the unsupported conspiracy theories of Maria Monk); in the specific, it manifested as attacks on Catholic places of worship (like the 1834 burning of Boston’s Ursuline Convent).

Well, if nativists thought the 1830s were bad, they thought the 1840s were a nightmare. Three million new immigrants arrived on our shores, making newly arrived immigrants almost 15% of the population. Nativists were quick to blame the new arrivals for everything they didn’t like about the nation’s current direction: economic stagnation, increased crime, and what they saw as moral decay.

Violent clashes between Protestants and Catholics were happening less frequently, but they were still happening with astonishing regularity. In 1844, Philadelphia’s Kensington neighborhood turned into a literal battlefield thanks to an ongoing debate over which version of the Bible to use as a textbook in public schools and whether public funds could even be allocated to parochial schools, which turned into a general debate over how to suppress the voting rights of the city’s burgeoning Catholic population. During the fracas Protestant mobs burned down two Catholic churches, a convent school, and numerous homes. As the ashes cooled, a grand jury assigned all the blame for the rioting on Catholics, for having the temerity to assert their civil rights.

While all that was going on, the Whig Party was self-destructing.

Frankly, it’s amazing the Whigs lasted as long as they did. The party started as elitist retrenchment in the face of Jacksonian ideas of democracy and popularism, and in its twenty years of existence never managed to form an ideology more coherent than, “make things better for the rich, maintain the status quo for everyone else, and block everything the Democrats want to do.” The problem was that individual Whigs often had very different ideas about what that meant, so the party quickly fragmented into multiple factions which agreed on very little.

Ultimately, it was slavery what did them in. The party ran General Winfield Scott for president in 1852, but Scott refused to endorse the party’s pro-slavery platform. That cost the Whigs Southern votes and handed the election to Democrat Franklin Pierce. In 1854 these same regional differences reared their ugly head again during debates over the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which, if you don’t remember your high school civics class, threw out the decades-old Missouri Compromise and gave territories the right to choose whether they should be a slave or free. Though that seems pretty neutral on first glance, it was actually a massive victory for slavery.

All I Know Is That I Don’t Know

After the Kansas-Nebraska act passed, Whigs began fleeing the party in droves and aligning themselves with fringe third parties that were a better fit for their personal ideologies. Many northern Whigs found themselves moving over to the American Party, which seemed to support their two key issues: abolition and temperance.

The American Party rarely ran its own candidates, preferring instead to throw its support to major party candidates who aligned with their goals. As a result, no one knew what they party was really about. That wound up benefiting them greatly, because it allowed Whigs to project their hopes and dreams onto a blank slate. A good modern comparison would be Ross Perot’s Reform Party, whose members were for “reform” but could not agree on what needed to be reformed and how.

At the start of 1854 the American Party had only a few thousand members, most of them concentrated in Norther cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. After the influx of Whigs they had more than 100,000 members across the entire country. They went from being perennial also-rans and never-wases to handily trouncing the Democrats and what little remained of the Whigs in head-to-head contests.

The leadership of the American Party knew that if they were going to transition from an unaligned voting block into a real political party they would need to clarify their political beliefs and voting principles. The problem with clarifying those beliefs was that their core members only agreed on one thing.

Sometimes, there’s nothing wrong with a simple answer. For instance, if someone asked you to name the root causes of the Civil War, you could just say slavery or you could rattle off any number of other issues — federalism vs. states rights, free trade vs protectionism, sectionalism — but frankly all of those other issues arise as a result of slavery, so just say slavery.

It’s much the same way with the American Party. Yes, they were pro-abolition and pro-temperance — but only because they were fundamentally anti-immigrant. The party started in the 1850s as a coalition of like-minded nativist groups. Its inner circle of leaders was a secret fraternal society called the Order of the Star Spangled Banner. Members of the Order were not allowed to discuss its principles, or even acknowledge its very existence. That earned the group a moniker which you do remember from history class: “The Know-Nothings.”

Their only real policy position Know-Nothings could agree on was that they were against immigrants and everything immigrants stood for. They wanted to stop all future immigration and require existing immigrants to be residents for twenty years before they could be naturalized. They were tough on crime because they thought all immigrants were criminals. They were for temperance because they thought all immigrants were drunks. They were for abolition because they mistakenly thought immigrants were pro-slavery (because it raised their wages by reducing competition or something like that). So of course they were also anti-Catholic, because immigrants were Catholic.

Here’s what the Know-Nothings believed in regard to religion.

- America was a Christian nation, by which they meant it was a Protestant nation.

- Catholic immigrants were undesirables being “dumped” on American shores by European nations trying to get rid of them. They were responsible for all of society’s ills, but especially for a rise in crime and a decline in public morality.

- Catholics by very definition could not be good Americans, because the structure of the Church itself was autocratic and anti-democratic. Priests and bishops encouraged ignorance in lay Catholics by shrouding their true beliefs with symbolism and mysticism, and emphasizing rote performance of rites and rituals over independent thought.

- Because Catholics were conditioned to do whatever ecclesiastical authorities said, they voted in massive blocks which gave them disproportionate political power, which is to say, any political power at all.

- Whenever Catholics gained political power they used it to force their beliefs on others. The public school debate was a perfect example, where they were trying to force schools to use the Catholic Douay-Rheims Bible instead of the good old King James Version (all other versions are per-versions).

- Therefore, though to outsiders the Know-Nothings and American Party seemed to be pro-active anti-Catholic bigots, they were actually re-active patriots defending the American body politic from foreign invaders.

Once those beliefs were clarified, Know-Nothings were ready to pick a fight with Catholics. Now, this is the third part of a three-part series, so I think you can guess the battlefield they wound up selecting: convents. Now all they needed was an excuse to go to war.

Miss Bunkley’s Book

Let’s take a quick trip to Maryland.

If you remember anything about Maryland from your high school history classes, it is that it was supposedly a “Catholic haven,” so you figure Catholics would have had an easy time there, right? Nope! They were allowed to freely worship, but that was about it. They still weren’t allowed to vote or hold public office until after the Revolution. In spite of that, Catholics were still pretty entrenched in Maryland and the state could boast more Catholic churches, monasteries, and convents than any other state.

That did nothing to help the state avoid the waves of anti-Catholic hysteria sweeping across the country. In 1839 a Sister Isabella Neale “escaped” from a Carmelite convent in Baltimore during a mental health episode, which inspired local nativists to attack the convent and demand that the nuns free the (non-existent) Protestant women being held prisoner inside. They were turned back by the militia but returned every night for three nights to protest and riot.

And then there was Josephine Bunkley.

Josephine was born in 1834; her parents were nominally Episcopalian but were not terribly religious. In her teenage years she was invited by Catholic friends to explore their religion, and was hooked. As a young woman she decided to become a nun, and entered the convent of the Sisters of Charity in Emmitsburg, MD as a postulant.

Once Josephine actually started living in the convent her idealized image of a religious life was shattered. The life of a nun was clearly not for her and as her postulancy came to an end she decided not to continue on to the novitiate — but when she announced her intention to leave to the Mother Superior, she was pressured and shamed into staying. That was bad enough, but the Mother Superior also made Josephine the target of her bullying. Eventually the young woman could take it no more, walked out the front door in the middle of the night, and hitchhiked to the next town over.

Now that Josephine was on the outside, she needed money. When local publishing house Dewitt & Davenport came looking for the rights to her life story, she seized the opportunity. Two ghostwriters, Charles Beare and Mary Jane Stith Upshur, expanded her threadbare story into something publishable. The resulting manuscript was first published as Miss Bunkley’s Book and later retitled The Escaped Nun, or, Disclosures of Convent Life and the Confessions of a Sister of Charity, Giving a More Minute Detail of Their Inner Life, and a Bolder Revelation of the Mysteries and Secrets of Nunneries, Than Have Ever Before Been Submitted to the American Public.

Miss Bunkley’s Book is a pretty standard convent memoir, along the lines of Rebecca Reed or Maria Monk, though more nuanced than the former and less sensationalistic than the latter.

Josephine soured on convent life almost immediately. About two months into her postulancy she received a litter from home which was intercepted by her superiors, who then embarrassed the young girl by mockingly reading excerpts to all the other nuns. Josephine started crying which led the nuns to physically discipline her. During the course of that she was thrown back, struck her head on the floor, and knocked unconscious.

That’s just her first complaint. Here are some of the others that she accumulated over the year.

- At night “strange noises” could be heard in the convent which spooked the young postulant. (So we know she has an overactive imagination.)

- The nuns maintained order and discipline with extreme measures, with punishments including being forced to tongue the sign of the cross on the floor, kneeling in stress positions, beatings and flagellation. Many nuns internalized this and also practiced other forms of self-mortification for sins real and imagined. (For a change these are actually real complaints that needed to be addressed.)

- She received “unwanted sexual attention” from priests. (This seems mean the occasional hug or chaste peck on the cheek, which I guess counts as assault if you’re a emotionally neutered WASP.)

- Nuns at the convent kept dying in mysterious ways. (On further examination the mysterious ways seem to be “old age” and “disease” but the book attributes their deaths to crossing the Mother Superior. More interesting is the fact that consumptive nuns were not isolated from other nuns, which meant tuberculosis was running rampant through the convent — sorry turned into John Green for a second there.)

- There’s an appearance our old favorite, “Catholics aren’t allowed to read the Bible.” (They absolutely are, it’s just not the Bible Protestants prefer.)

- There are complaints about things endemic to any large organization, favoritism, cliquishness, inefficiency, and reluctance to change. Some other complaints seem to be about a few weird individual nuns. (Of course, these are blown way out of proportion and used as an indictment of the entire convent system.)

- The actual nature and meaning of the vows taken by novices and nuns was hidden from her until the very end of her postulancy. (That’s not good.)

- Despite being told that postulants and novices were free to leave at any time, when Josephine decided to end her postulancy the Mother Superior browbeat her into staying by making her feel like she hds no other options. (That’s not good either.)

- The straw that finally broke the camel’s back came when Josephine receivds a letter from her sister, offering to come take her home. The Mother Superior once again read it out loud to the other nuns and claimed she would never allow it to happen. (That’s really, really bad — but also sounds like it’s been exaggerated for effect.)

- After her escape were several other strange incidents which are interpreted as attempts by the Jesuits to recapture her and return her to the convent. (And which actually didn’t happen.)

- Here allegations are “backed up” by letters detailing the stories of other nuns who were unable to “escape” from the convent. (It’s worth noting all these anecdotal accounts are all pseudonymous and unsubstantiated.)

One thing you may have noticed: unlike the other two books we’ve covered, there are some actual valid criticisms of the convent system mixed in with the same old knee-jerk anti-Catholic stuff. The problem is that those criticisms get lost in the shuffle because the signal-to-noise ratio is awful.

You know who else agreed with that assessment? Josephine Bunkley.

When she saw what Beare and Upshur had done to her story, she was angry. She had wanted to tell her actual story and make a serious criticism of the convent system. When she saw that the ghostwriters had taken her outline and turned it into a conspiratorial anti-Catholic screed, she got upset. So she sued Dewitt & Davenport to stop it from being published.

Dewitt & Davenport put up a good fight, trying to claim that the extensive revisions had turned Bunkley’s manuscript into a substantially new work which she had no authorial interest in. Their attorney also inadvertently made a damning revelation: the publishers really didn’t care whether the book was true or not, because they were backed by the American Party and their primary interest was in producing nativist propaganda they could be distributed in advance of upcoming state elections. (Making them the Regnery of their day.)

Those arguments didn’t go over well in a court of law, and a judge issued an order prohibiting them from publishing the book with Josephine Bunkley’s name attached. She had won.

Except she hadn’t.

When it became clear they were going to lose, Dewitt & Davenport stereotyped the book and ran off several thousand copies before the judge’s order came down — the order did not prohibit them from selling off existing inventory. They also leaked excerpts to newspapers all over the country. And then they sold the copyright to the Harper Brothers, who were able to print up more copies because the injunction was attached to the publisher and not the manuscript.

Thankfully for Josephine, the book did not sell terribly well and did not have many lasting effects. Unfortunately, it still sold well enough to destroy her personal life. After its publication her Catholic friends wouldn’t have anything to do with her. Even when she swore up and down that the book did not represent her actual views.

The Smelling Committee

Miss Bunkley’s Book may not have had any lasting effects but it did have some immediate short-term effects.

The Know-Nothings cleaned up in the 1854 Massachusetts elections, winning every seat in the Senate, 375 of 378 seats in the House, and the governorship. They immediately started implementing their anti-immigrant agenda, disbanding militia companies with immigrant members, evicting immigrants from public almshouses and deporting then back to Europe, and instituting a literacy test at the polls.

Know-Nothings also used the momentary furor created by Miss Bunkley’s Book to implement anti-Catholic measures, mostly targeted at schools. They barred the use of state funds for parochial schools; forced public schools to use the King James Bible instead of the Douay-Rheims Bible; and required all students to read from that Bible daily. Just for spite they also banned the teaching of all foreign languages. Mostly they were trying to stamp out Latin, on the grounds that if English was good enough for Jesus and King James it should be good enough for anyone.

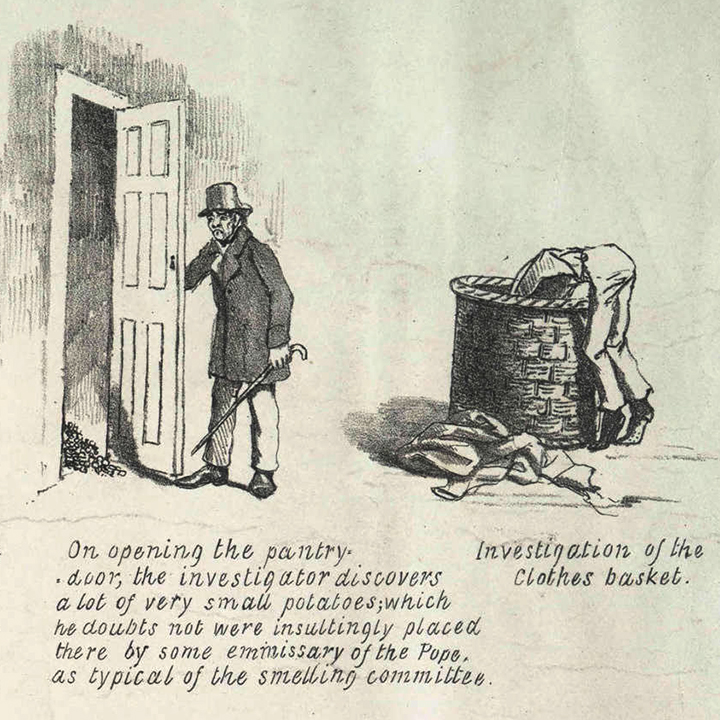

They didn’t forget about convents, either. On February 18, 1855 the legislature established a Joint Special Committee on the Inspection of Nunneries and Convents, or, as it was later more popularly known, “The Smelling Committee.” (Because it stunk, see?) It had seven members from all over the commonwealth, but the only you really need to care about is Joseph Hiss, who was also the “Grand Worshipful Instructor” of the Order of the Star Spangled Banner’s Boston Chapter. The Committee was empowered to investigate convents for sexual misconduct and other irregularities — not that there were any specific allegations of wrongdoing, mind, you just a general sense that something fishy was going on. At the time there were only five convents in the entire commonwealth, and explicit anti-Catholic legislation seemed a bit wonky on First Amendment grounds, so the Committee was also given the authority to search “theological seminaries, boarding schools, academies, nunneries, convents and other institutions of a like character.” They didn’t have any actual intent to search Protestant institutions, but it was a nice CYA move.

The Smelling Committee went on three excursions. They conducted a surprise inspection of a Catholic College in Worcester on March 25; of a Catholic school in Roxbury on March 26; and of another Catholic school in Lowell on March 29. There were likely more on the schedule, but Catholics not struck back on March 31. They focused most of their ire on the Roxbury trip, which sounded like an utter fiasco.

At 11:30 AM on March 26, two omnibuses carrying somewhere between sixteen and twenty-four men pulled up in front of the school. You will remember that the Committee only had seven members — the surplus seems to have consisted of relatives, friends, and other assorted hangers-on invited along for the ride. They rang the doorbell and announced themselves thus: “We are a committee of the Massachusetts Legislature, delegated with authority to visit this and other institutions of instruction in this Commonwealth, in order to gain information of their condition, and report it to that body. Have you any objection to an investigation?”

The school’s residents, which consisted of seven Catholic nuns, twelve teenage girls, and an elderly Irish groundskeeper, were shocked. Two dozen angry looking strangers were crowded onto their stoop, drinking and smoking and tapping their canes, and refusing to provide any proof of identity. They allowed the men in, but did not really feel like they had much choice in the matter.

The girls were agitated, and began shrieking “The house is full of Know-Nothings!” but the nuns quickly quieted them down. For the next half hour the Smelling Committee turned the house upside down, poking their nose into every nook and cranny, from the classrooms to the chapel to the kitchen to the bedrooms. They did not even have the decency to put down their bottles of whisky or snuff their cigars. Just after noon the men piled back into their omnibuses and departed just as suddenly and unexpectedly as they had arrived.

Catholics had spent the fifteen years since Maria Monk formulating an effective response to Protestant incursions. Rather than respond with facts or logic, they had crafted an emotional appeal of their own.

This was not some stone fortress where women were being held prisoner agains their will. This was a home, where these women lived, and this unreasonable search was not only a violation of their Constitutional rights but against all social propriety and decorum. The main thrust of the argument was most clearly expressed by Charles Hale of the Boston Daily Advertiser:

This establishment is kept in an ordinary house, situated upon the Dedham turnpike, in Roxbury, just beyond Oak Street. The spot possesses considerable natural beauty; the house is an old one and badly out of repair. The girl who could not escape from its weak fastenings, if any attempt should be made to confine her there, would scarce deserve her freedom. The house is situated upon an open piece of land, surrounded by a low stone wall that a child could climb. There is also a wide gate-way, and the gate, a fragile structure, is always open…

If any man describes the manner in which he entered a lady’s bedchamber and asks me, “How could I have done it in a more gentlemanly manner?” I can only answer, You should not have done it at all. The act is so gross, so repulsive to all notion of refinement, that no gentleman can perform it except for some necessity, such as did not exist in the present case. There is no gentlemanly way for a man to enter the bedchamber of a lady who is an entire stranger to him. The place is sacred to itself. If a man’s house is his castle, how much more is the apartment in a house occupied by a lady, her own castle, so retired and so private the intrusion is intolerable! The nineteen men who went to Roxbury on the 26th visited every chamber in the house. Let them all swear that their visits were perfectly “gentlemanly” if they please — the word has a strange meaning to them.

Charles Hale, “Our Houses are Our Castles”

It was a pretty convincing argument. Nativists struck back, claiming that they had to conduct surprise inspections because otherwise Catholics would be able to hide the nuns they were secretly holding in prison, but no one was buying it. Catholics also pointed out that that a half hour search was hardly exhaustive.

Just in case the first argument hadn’t worked, the Catholics also drew attention to the Committee’s expense reports. Those three trips should have been simple there-and-back excursions, taking no more than a few hours and costing the commonwealth no more than a few bucks. And yet in Worcester they somehow managed to run up a tab of $99.90 over just a few hours. In Roxbury the legislators and their guests stayed overnight in a fancy hotel and ran up a huge bill at the nicest restaurant in town. The Lowell trip turned into several days of sight-seeing. The approved expenses included expenditures on cigars and alcohol, including beverages like champagne (which at the time was prohibited by law).

The legislators didn’t have much of a defense there, except that those who love sausages and the law shouldn’t look too closely at how they were made. No one was buying it.

Just in case the second argument didn’t work, Catholics also pointed out that in Lowell the expense report included lodgings for a lady friend of Joseph Hiss, one “Mrs. Patterson.” Hotel employees reported that no one had stayed in Hiss’s room, but two people had spent the night in Patterson’s.

The legislators had no response to that.

It’s not clear whether people were swayed by Hale’s eloquent arguments, angered by the obvious corruption, or enraged by the idea that a state legislator was keeping his mistress on the public dime. (Probably a little of all three, but mostly the last one.) Hiss was officially censured and removed from his post by a 230-30 vote. Savaged by the press and hounded by creditors, he ultimately resigned. The fuss kicked up by the press crippled the operations of the Committee, which did nothing of note for the rest of the year and was disbanded at the end the legislative session.

In their final report the Smelling Committee declared victory, claiming that the threat of surprise inspections had led the convents in the state to clean up their act, and blaming Jesuit trickery for their failure to unearth any malfeasance. (Always the Jesuits.)

That report went right into the circular file, and deservedly so.

Our Homes Are Our Castles

As it turns out 1855 was the high water mark for the Know-Nothings.

Part of the problem was that building their organization with former Whigs meant they wound up inheriting all of the Whig Party’s problems with factionalism and sectionalism. Things finally came to a head in 1856 when Know-Nothing leadership introduced a loyalty oath requiring party members to never threaten the unity of the country. Northern abolitionists correctly interpreted this as a move by Southerners to neuter the party’s position on slavery, and noped out for the newly formed Republican Party.

They were not alone. Many voters and legislators who had been projecting their hopes and dreams onto the Know-Nothings got a shocking wake-up call when the party’s governing strategy turned out to business as usual. By 1856 the party had stopped promoting themselves as agents of change, and started promoting themselves as the protectors of the status quo. Because that had worked so very well for the Whigs.

It didn’t help that their anti-immigration and pro-temperance legislative agenda somehow managed to unite immigrants and drunks into an unstoppable force. And, you know, the naked bigotry probably didn’t help either.

As with many things, Abraham Lincoln put it best.

When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read “all men are created equals, except negroes and foreigners and Catholics.” When it comes to that I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.

Abraham Lincoln, personal correspondence to Joshua Fry Speed

The Know-Nothings were decisively trounced in the 1856 elections. The American Party presidential candidate, Millard Fillmore, came in a distant third with only Maryland’s 8 electoral votes and 20% of the popular vote. Candidates further down the ticket fared no better. By 1857 the party was de facto done, though they somehow managed to hang around until 1860 when they were officially dissolved.

They’ve never really left us, though. They just got better at keeping the quiet parts quiet. And usually hidden behind a screen of honeyed words and more popular platforms.

Connections

Josephine Bunkley’s ghostwriter Mary Jane Stith Upshur was the niece of John Tyler’s Secretary of the Navy, Abel P. Upshur, who got blown to pieces during an artillery accident on the USS Princeton. We told that story in the episode “Peacemaker.”

Sources

- Anbinder, Tyler. Nativism & Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings & the Politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University PRess, 1992.

- Archdeacon, Thomas J. Becoming American: An Ethnic History. New York: The Free Press, 1983.

- Berman, Cassandra N. Wayward Nuns, Randy Priests, and Women’s Autonomy: Convent Abuse and the Threat to Protestant Patriarchy in Victorian England. St. Paul, MN: Macalester College, 2006.

- Billington, Ray Allen. The Protestant Crusade, 1800-1860. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1964.

- Bracken, Maureen and McCusker, Luke. “The Tyranny of Mobs: Threats and Violence against Irish Catholics in Baltimore and Elsewhere.” The Irish Railroad Workers Museum. https://www.irishshrine.org/big-pivot-posts/the-tyranny-of-mobs-threats-and-violence-against-irish-catholics-in-baltimore-and-elsewhere Accessed 5/13/2023.

- Bunkley, Josephine M. Miss Bunkley’s Book: The Testimony of an Escaped Novice from the Sisterhood of St. Joseph, Emmettsburg, Maryland, the Mother-House of the Sisters of Charity in the United States. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1855.

- Carey, Patrick W. “The Confessional and Ex-Catholic Priests in Nineteenth-Century Protestant America.” U.S. Catholic Historian, Volume 33, Number 3 (Summer 2015).

- Hale, Charles. “Our Houses are our Castles”: A Review of the Proceedings of the Nunnery Committee of the Massachusetts Legislature. Boston: Charles Hale, 1855.

- Hofstadter, Richard. Anti-Intellectualism in American Life; The Paranoid Style in Amercan Politics; Uncollected Essays 1956-1965. New York: Library of AMerica, 2020.

- Mercado, Monica L. “Have You Ever Read? Imagining Women, Bibles and Religious Print in Ninteenth-Century America.” U.S. Catholic Historian, Volume 31, Number 3 (Summer 2013).

- Myers, Gustavus. History of Bigotry in the United States. New York: Random House, 1943.

- Yacovazzi, Cassandra L. “Are You Allowed to Read the Bible in a Convent? Protestant Perspectives on the Catholic Approach to Scripture in Convent Narratives, 1830-1860.” U.S. Catholic Historian, Volume 31, Number 3 (Summer 2013).

- Yacovazzi, Cassandra L. Escaped Nuns: True Womanhood and the Campaign Against Convents in Antebellum America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- “Joseph Hiss.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Hiss Accessed 5/15/2013.

- “Know-Nothing.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Know_Nothing Accessed 5/15/2013.

- “The Convent Committee, better known as the Smelling Committee, in the exercise of their onerous and arduous duties at the Ladies Catholic Seminary, Roxbury.” Boston Athenaeum. https://cdm.bostonathenaeum.org/digital/collection/p13110coll5/id/1840/ Accessed 5/15/2013.

- “Escape of a young lady from the Roman Catholic sisterhood.” Recorder, 1 Jan 1855.

- “Case of Miss Bunkley.” Daily American Organ, 14 Mar 1855.

- “The case of the escaped nun in court.” New York Herald, 4 May 1855.

- “The case of the escaped nun.” New York Herald, 8 May 1855.

- “The convent matter.” Brooklyn Evening Star, 9 May 1855.

- “The Know-Nothing proscription.” Hamilton Spectator, 24 May 1855.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: