Nuns on the Run

Six Months in a Convent

This is part one of a three-part series about escaped nuns and anti-Catholicism in early Nineteenth Century America. You don’t have to read the entire series to understand each individual story, but it would provide extra context that might be helpful. Part two, about Protestant activists who claimed that convents were vice dens in 1836, can be found here. Part three, about attempts by the Know-Nothings to use anti-Catholic propaganda to sway elections in 1854, can be found here.

It took a long time for the United States to come to terms with Catholicism.

It’s well-known that the British colonists who settled in the New World were not seeking religious freedom in the modern sense, where everyone is free to practice their own religion, but were only seeking the freedom to practice their religion, everyone else be damned.

While Protestants eventually learned how to play nice with other Protestants, Catholics were excluded from their little club. Most American Protestants cleaved to prejudices formed in the early days of the Reformation. They mocked Catholics as superstitious ignorant foreigners whose loyalty to the Pope made their loyalty to the Crown suspect. As a result Catholics were discriminated against both privately and publicly: they were not considered full citizens and were granted only limited civil rights. The discrimination wasn’t exactly quiet, either. In New England celebrations of “Pope’s Day” on November 5 included parades where marchers sang anti-Catholic songs and typically ended with throwing effigies of the Pope and the Devil on a bonfire.

For the most part this anti-Catholicism was largely theoretical. There were few Catholics in the colonies, because there were few Catholics left in England to emigrate. That changed after the French and Indian War, when the United Kingdom added Canada to its colonial holdings. Canada was very French and very Catholic, which was a constant source of conflict between the conqueror and the conquered.

In 1774 Parliament attempted to de-escalate that conflict by passing the Quebec Act, which granted freedom of worship to Canadians and a restored full civil rights to Catholics. Paranoid Americans worried the British were laying the groundwork for a Catholic takeover of the entire continent. That year’s Pope Day celebrations saw the appearance of a new effigy on the bonfire: King George III.

Anti-Catholic sentiments were deliberately suppressed during the Revolutionary War, when the colonists were trying to win over Catholic allies including the French and Canadians. After the Revolution freedom of religion was guaranteed in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, and for the first time Catholics in the United States could worship openly.

Mt. Benedict

Catholics were still a distinct minority until the 1820s, when there was a massive influx of immigrants from Ireland and Germany. Within a decade Catholics became the largest single Christian denomination in the country, a state of affairs which persists to this very day. (Protestants as a whole outnumber Catholics 2:1, but Catholics outnumber the largest individual Protestant denomination 4:1.)

Nativists believed that immigrants were responsible for the decline of civic institutions and a rise in crime. Since the majority of the new arrivals were Catholic, nativists were reflexively anti-Catholic. Catholics were decried as intellectually incurious children, prone to believe in superstition and the supernatural, who valued form and ritual over faith, and were more loyal to the Pope than to the President.

America’s White Anglo-Saxon Protestant elite led the charge. Samuel F. Morse, the country’s greatest inventor, believed mass Catholic immigration was a plot by organized by Klemens von Metternich and the Bavarian Illuminati to put a Catholic Hapsburg monarch on the throne of America. The Reverend Lyman Beecher, the country’s most famous preacher (and father of Henry Ward Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe), preached that the invading Catholic hordes did not respect American values, prophesied that their refusal to assimilate would undermine our civic institutions, and called for the government to deport them all.

The lower classes were more direct in their approach: whenever they felt Catholics were getting “out of hand” they rioted. It didn’t take much to get the nativists reaching for their truncheons. Boston, for instance, had sprawling anti-Catholic riots in 1823, 1826, 1828, 1829, and 1833. Some of the riots were triggered by political issues like education and welfare, others by economic issues like wages and competition, and some even by petty personal grievances like beat whom in a bar fight.

Then there was the time Bostonians picked a fight with some nuns.

Protestants have always been weird about nuns, but in the Nineteenth Century they were really weird about nuns. They tended to view convents as a perversion of the normal order, which channeled women away from their “natural” role as wives and mothers and into an unnatural celibacy and seclusion, where they labored not for proper material but the vain pursuit of spiritual brownie points. Clearly no woman would voluntarily choose such a debased existence, so nuns must have been seduced into it by priests and bishops. Even if they eventually realized that they had made a horrible mistake they were trapped, not only by social and religious pressure, but by the physical structure of the convent itself. (Is it a coincidence that both prisons and convents have cells? I think not.)

As a result, many anti-Catholic Protestant crusaders viewed themselves as white knights trying to save good Christian girls from the life of a dusty old maid trapped in eternal servitude to the Pope.

The Ursuline Order had been a presence in Boston for decades, but when the city’s Catholic population increased they acquired a small plot of land at the foot of Mt. Benedict in Charlestown and built a lovely convent. It was a grand building of solid brick, with beautiful terraced gardens, even a small cemetery. It was perhaps too grand for the six nuns that were its only full-time residents. The nuns also ran a finishing school out of the convent, where they taught young ladies everything they needed to know to be good wives and mothers. (Because who better to teach you that than a nun.)

Nativist locals hated, hated, hated the convent.

Protestants hated it because it made them realize how far they had fallen. Most of the school’s students were Protestants, the children of wishy-washy Unitarian types who might has well have been secular. That they would prefer a Catholic education to a proper Protestant one was a slap in the face.

The patriots disliked the idea that a foreign prince like the pope had built a Catholic stronghold only a stone’s throw the birthplace of American liberty, Bunker Hill. They fought tooth and nail to prevent the Church from acquiring more land in the area, and even changed zoning laws to prevent a Catholic cemetery from opening nearby.

The poor were not happy that a finishing school for rich young ladies had been plunked down in the middle of a working class neighborhood. Other factors presented them from acting on their class resentments, so they were sublimated into religious hatred.

The xenophobes just hated anything related to immigrants and papism.

And everyone hated the Mother Superior, Mary Anne Moffat or Mother St. George. She was a #girlboss in every sense — a strong-willed woman with a singular vision who wouldn’t take crap from anyone, who could also be mean-spirited, short-tempered, and imperious if she didn’t get her way. Over the years her prickliness created quite a few enemies she would have to deal with later.

Rebecca Reed

Enemies like Rebecca Theresa Reed.

Reed was born in 1813, the youngest daughter of poor farmer William C. Reed. Her early life was utterly unremarkable until her teen years, when she decided to act out. Her version of “acting out” was to become religious.

This isn’t that unusual. Most people question the religion they were raised in at some point — children of devout families experiment with atheism, children of Christians experiment with world religions, etc. etc. In this case, the child of non-churchgoing Protestants became a devout Catholic.

If that seems strange to you, consider this. If you are a tween drama queen in an era before Archie and Shaun Cassidy and Twilight there is no better source for tragedy, romance, and melodrama than the lives of the saints and martyrs. Who could resist turning their pillowcase into a wimple and pretending they were about to be killed for their unshakeable faith in Christ?

Also, if your interest in religion is not doctrinal but aesthetic, Catholicism handily beats Protestantism, which has deliberately purged itself of all the cool rituals and clothes and art and architecture.

What sealed the deal in Rebecca Reed’s case was a visit to the convent. To a thirteen-year-old used to backbreaking farm labor, the genteel pace of life at the convent must have seemed like Heaven. From that moment on she had only one goal in life: she was going to be a nun.

William C. Reed put his foot down. It was bad enough that his daughter was flirting with papism, but he would be damned before he would let her be a nun. Rebecca responded by running away from home to a nearby Catholic neighborhood. She was quickly welcomed into the community, started going to Mass, and was eventually baptized. Eventually she began asking the nuns if she could join the convent.

Mother St. George wasn’t keen on the idea. She believed that Rebecca’s newfound religiosity was a passing fancy, that her faith was shallow and superficial, her vision of convent life a childish fantasy. She politely gave the young girl the brush-off.

Only to be overruled by the local Bishop, who wanted every convert he could get. On August 7, 1831 Rebecca Reed entered the Ursuline convent at Mt. Benedict as a postulant.

(If you are not Catholic and unfamiliar with how convents work, here is a gross oversimplification. When a candidate first enters the convent they become a postulant. This a trial period so they can figure out whether the religious life is right for them. A fully committed postulant becomes a novice, and their time is devoted to prayer and study. After a few years the novice takes their vows and becomes a full-fledged nun.)

Rebecca Reed immediately began proving Mother St. George right.

She came to our Community, doubtless, in the belief that she would have nothing to there, but to read, meditate, and join in our prayers. She found that every hour had its employment, and that constant labor was one of the chief traits of our order. The novelty of the scene wore away, and the hours, she imagined she would spend with so much delight as an inhabitant of a cloister, she found, to her sorrow, appropriated the duties of everyday life.

Mother St. George

Rebecca Reed’s parents were not terribly religious; she had only an unconscious understanding of Protestantism and no understanding of Catholicism at all. She showed no interest in trying to rectify her ignorance by studying her Catechism, either. Actually, it would be more accurate to say she had no interest in any sort of work whatsoever, and frequently shirked her chores and ignored her duties.

Most importantly, Rebecca Reed did not understand that becoming a nun meant withdrawing from the secular world. She corresponded openly with her sisters and school friends, and on several occasions tried to sneak out to attend parties in town. Mother St. George quickly put an end to that by banning Rebecca’s friends from the convent, but may have also overstepped her bounds by confiscating and destroying letters meant for her charge.

After a few months it became clear that Rebecca Reed did not understand what she was doing and wasn’t putting any work into her spiritual development.

Mother St. George sat down with Bishop Fenwick and tried to persuade him to let her go. The Bishop insisted that they explore other options instead. If the local environment was full of distractions, they could either remove those distractions from Rebecca, or remove Rebecca from those distractions. He floated the idea of transferring the troublesome postulant to a convent in Quebec, where she might flourish under a different Mother Superior.

Unfortunately for them, Rebecca Reed was eavesdropping on the meeting. She started entertaining fantasies that the Church was isolating her from her friends and family, holding her prisoner against her will, and plotting to spirit her out of the country for nefarious purposes. In her paranoid state she made a “daring escape” from the convent in January 1832, waiting for a moment when she was “unguarded” to break some lattices in the garden, use them to climb over a nearby wall, and run to a neighbor’s house.

It was hardly necessary. The front door was wide open and Reed was free to leave at any time.

It was also hardly clandestine. Rebecca’s “escape” made such a racket that Mother St. George interrupted her class and invited all of the students to come over to the window “to see Miss Reed run away.”

Rebecca Reed renounced Catholicism and returned to Boston. She became a music teacher and seamstress, with a small side gig retelling her adventures as a cautionary tale for young Protestant ladies. With each retelling the story became more exaggerated and grandiose. She promoted herself to a full-blown nun; the mild discipline she was subjected to became excruciating torture; and her proposed transfer to Canada became part of an international sex trafficking ring.

The Protestants of Boston couldn’t get enough.

The Burning of the Convent

By 1834 Catholic/Protestant relations in America were at a low point, because Catholic had decided to fight back instead of meekly presenting the other cheek. And when I say fight, I do mean fight. Catholic immigrants interrupted lectures and sermons, chased anti-Catholic crusaders through the streets, and beat their Protestant oppressors to the punch by starting their own riots. America’s cities were on edge.

Charlestown was no exception. It was a tinder box ready to burn, and several sparks were about to set it off.

First there was Peter Rossiter, the Ursuline convent’s groundskeeper. Locals had started taking shortcuts across the convent grounds, damaging the meticulously groomed garden and lawns. When Rossiter politely asked trespassers to cut it out, they just laughed in his face. On July 28 Rossiter snapped and set his dog on a group of trespassing youths. (Like, I feel your pain, Pete, but not cool, man.) A local brickmaker named John Buzzell took offense for obscure reasons, and started a fight with Rossiter which ended in a draw. Both men walked away licking their wounds and planning for round two.

Then there was Sister Mary John, Mother St. George’s second-in command. Sister was not entirely suited for the job, but despite her obvious struggles the Mother Superior kept settling new responsibilities on her shoulders. The stress eventually caused a nervous breakdown, and Sister Mary John left by walking through the front door (see, Rebecca?) and sprinting to the farm of neighbor Edward Cutter. She vented to Cutter, complaining about the Mother Superior’s management style and swearing she would never return to the convent — and then collapsed on the kitchen floor. Mother St. George and Bishop Fenwick quickly located the missing nun, and with some work persuaded her to come back to the convent where they would give her all the time she needed to rest and recuperate. Sister Mary John agreed and willingly went with them.

The local rumor mill told a different tale about Sister Mary John’s escape, influenced by anti-Catholic propaganda and Rebecca Reed’s stories of convent life. It claimed that the nun had not willingly returned to the convent but had instead been dragged back kicking and screaming. Now that the Catholics had her back in their vile clutches she was surely being tortured using the methods of the Inquisition. Eventually, of course, she would be bricked up alive in the convent’s “dungeons,” like the noble Constance de Beverly in Sir Walter Scott’s Marmion.

Enter the Boston Truckmen. They were a local association of labors that functioned like a social club crossed with a mutual aid society — sort of like a union but without the collective bargaining power. (Think of them as the Teamsters and you’re halfway there.) They circulated pamphlets all over town recounting the salacious rumors about the convent and Sister Mary John’s escape, casting the young nun as a noble and virtuous girl who had rejected the false Christianity of Catholicism only to be recaptured by the Mother Superior, the Bishop, and their Jesuit minions. (It’s always the Jesuits with these people.) The Truckmen called on local Protestants to storm the convent, free the women held prisoner inside, and then tear it down brick by brick. (Oh, did I mention John Buzzell was a Truckman? He was a Truckman, all right.)

Tempers were starting to flare, so Charlestown’s selectmen finally decided to intervene. In early August the selectmen went to the convent and announced they were there to search the grounds for young women being tortured. Well, Mother St. George was not in the mood to be ordered around by uppity Protestants and their elected officials. She denied the request and was about to tear them a new one when Sister Mary John stepped in. Sister assured the selectmen that she was fine, that rumors of her “abduction” and “torture” were just rumors, and she just neeed some rest. The selectmen left satisfied that nothing sinister was afoot, but for some reason decided to keep that fact to themselves.

Our final figurative spark is the Reverend Lyman Beecher. He had left Cincinnati on a lecture tour, which brought him to Boston on August 10. There he delivered a series of blistering anti-Catholic sermons. Their subject matter wasn’t anything new, but their tone was — the usually restrained Beecher was now full of fiery invective and passionate please from action. The Boston Truckmen’s anti-convent campaign had been losing steam, but Beecher’s sermon re-energized it.

On August 11 a lone selectman visited the convent to warn the nuns that an attack of some sort was imminent. He graciously offered a solution: if they allowed him to see the basement for himself he could go to the Truckmen and tell them the dungeons were just a fantasy. Mother St. George was about to dress him down when once again Sister Mary John Changed her mind. Instead she threw open the cellar doors and sneered, “If you want to play spy in my house, you shall do it alone.” The selectman took one look down the narrow stairs into the pitch darkness of the cellar… and chickened out.

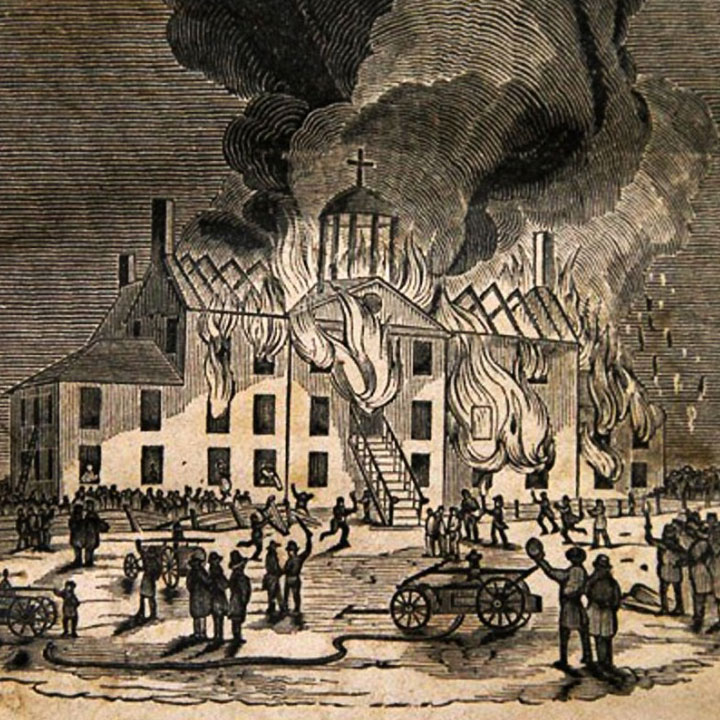

As the sun fell that night a large mob assembled on the convent’s lawns. There were hundreds of them — Boston Truckmen, sailors, nativist hoodlums, curious locals. They had all been drinking, and continued to drink as they sat on the lawn chanting “No Popery!” and “Down with the Cross!”

Several of their number approached the convent, knocked on the doors, and demanded to be let inside. From the safety of a second story window, Mother St. George replied that the nuns and their students were trying to sleep, and told the crowd to go home and come back in the morning. Her refusal only angered the mob. They began to chant harder, demanding that she throw open her dungeons and free the “mysterious lady” imprisoned inside.

As midnight approached they started lighting tar barrels, tearing down garden fences for kindling, and making bonfires. Mother St. George had seen enough. She flung the convent doors wide open and began hurling insults at the mob, calling them vagabonds and drunkards, and claiming that if they didn’t leave now Bishop Fenwick would raise an army of ten thousand Irishmen to “sweep them into the sea.”

It was the worst possible thing she could have said.

Two pistol shots rung out, one of them slamming into the door behind the Mother Superior. She was momentarily stunned but recovered her wits and dashed back into the convent. At the same time a group of about a hundred men, their faces painted like Native Americans Braves in imitation of the Boston Tea Party, launched a clearly organized attack.

Screaming “Down with the Pope! Down with tyranny!” they broke down the front doors, started systematically looting, and set the building on fire. The nuns and their fifty students escaped through the back door and briefly sought refuge in a crypt. When rioters began heading their way, they made a run for it. Edward Cutter helped them over a garden fence to safety on his farm.

At this point Charlestown’s emergency services arrived on the scene: a single part-time police officer, and a whole fire company. They all decided that quelling a riot was way above their pay grade, sat back, and enjoyed the show. Some of theme even joined in.

Now the rioters were on a roll. They dropped a piano out of a second story window with a mighty crash, paraded around in the students’ spare frocks like deranged mummers, tossed all the books into the fires, and then moved on to the cemetery where they dug up the corpses and put on a macabre puppet show. They uprooted the gardens, felled all the trees, and burned Bishop Fenwick’s house for good measure.

When the sun rose over the horizon, the mob melted away as if it had never even existed. It would have all seemed like a strange nightmare, if not for forty-seven terrified girls and the burning husk of the Ursuline convent.

Ember Days

Well, that and the fact that the rioting resumed the next evening and continued for several more days. In response to rumors that the Irish were forming an army to come get their revenge, Protestants took to the streets to “defend themselves” by attacking Irish homes and Catholic churches. Local grandees responded by calling out the militia — not to protect the Irish or the Catholics, mind you, but to protect their precious private property.

On the morning of August 12 a small notice from the Charlestown selectmen ran in local newspapers, stating that they had personally investigated the convent and there was nothing funny going on, so everyone could calm down now. Too little, too late, selectmen.

Boston’s well-to-do WASPs were horrified. Sure, they were all for getting rid of Catholics, but violence was so declassée. Lyman Beecher tried to put some space between himself and the rioters, claiming that his sermons were not intended to be rabble-rousing, and expressing utter bewilderment that anyone would take his call to action as a call to action. At the same time he defended the assault as the noble action of a concerned citizenry responding to Catholic threats of violence, conveniently ignoring the fact that Catholic threats had been made in response to Protestant threats. Later that year he even published a pamphlet calling for religious tolerance, though his idea of “tolerance” seemed to be that Catholics should just shut up, take it, and just be grateful that Protestants allowed them to stay in the country at all.

Samuel Morse went in the exact opposite direction. He claimed that that Mother St. George’s ill-timed utterances on August 11 proved that Pope Gregory XVI and his Jesuits were conspiring with Holy Roman Emperor Francis I and his Bavarian Illuminists to overthrow America with an army of Irish infiltrators. (We probably won’t be doing a full episode on Morse any time soon, but you should definitely look into him because he was a deeply, deeply unpleasant man.)

Faneuil Hall put together a blue-ribbon commission to investigate the events of the evening. Eventually it released a report concluding that the root causes of the arson were a local distrust of Catholics, exacerbated by Rebecca Reed’s gossip and rumors about Sister’s Mary John’s attempted “escape.” Gee, you think? Your taxpayer dollars at work, folks.

At some point it became obvious that someone was going to take the fall.

The Boston Truckmen panicked, because they knew it would be them. The blanketed the community with flyers threatening to kill anyone who ratted them out to the authorities. It didn’t work. Thirteen Truckmen were arrested, including John Buzzell. Also arrested was Prescott P. Pond, one of the firemen who had joined in the looting (and also Rebecca Reed’s brother-in-law, and possessor of the most delightfully Bostonian name I’ve ever heard).

The trial started on September 14. It should have been a cut-and-dried case: dozens of people had witnessed the Truckmen planning and executing the attack, and also their feeble attempts to cover up their involvement. Unable to use a real legal defense, the Truckmen’s attorney George Farley did the only thing he could: he tried to shift the blame on to the victims by making the trial a referendum on Catholicism. He read passages from the Bible into the court record, called anti-Catholic witnesses including Rebecca Reed to the stand, and made openly prejudicial statements to the jury.

And it worked.

The jury found most of the rioters “not guilty.” The presiding judge thought it was the worst miscarriage of justice he had ever seen in all his years on the bench. Which raises the question of why he’d allowed it to happen in the first place.

It really shouldn’t have been a surprise. There were hundreds of rioters that night. Almost everyone in the jury pool would have either been at Mt. Benedict or known someone who was there, and they were disinclined to think that the “good people” they knew had done anything criminal. (As an example, in our episode about the last day at Connie Mack Stadium, I got in an argument with a YouTube commenter who didn’t think the events of that night should be classified as a riot. Eventually it became clear that he had been there that night and participated in the “festivities” and didn’t want to think he had done anything boorish. How can you argue with that?)

Only one rioter was convicted: a 17-year-old boy named Marcy who had staged a mock auction of several books before throwing them on the bonfire, who was found guilty as charged. That, finally, outraged the public. A young boy going to jail for some innocent tomfoolery? Surely he deserved some clemency. Let boys be boys. The governor was bombarded with petitions demanding a pardon for Marcy, and curiously many of them were signed by Catholics. I guess they figured if you were going to let the ringleaders go unpunished you might as well let the whole lot go. Marcy got his pardon.

Six Months in a Convent

During the trial Rebecca Reed decided to cash in on her newfound infamy by publishing a book about her experiences at the Ursuline convent. Those experiences were pretty thin, though, so she joined forces with a ghost writer, an anti-Catholic activist named William Crosswell who could provide extra context on the villainy of the Catholic Church and the perversities of convent life. Their work was eventually published as Six Months in a Convent: A Narration of Facts.

There’s no way around it: it’s bad, really bad, and confirms every sneaking suspicion Mother St. George ever had of her one-time postulant.

The majority of the story is nothing more than a litany of petty complaints from a callow young girl who thinks the great injustice of the world is that it is not entirely organized for her own personal benefit. She did not like being bossed around by anyone; she did not like being disciplined; she did not like working; she did not like kneeling all the time; she did not like the quality of the food in the cafeteria. Fundamentally, she does not seem to grasp that the life of a nun is not one of leisure but one of thankless hard work, and that she actually has to put in that hard work to receive any of the perceived benefits.

The rest of the book is the “context” provided by Crosswell, and it’s mostly knee-jerk xenophobia, of the “well this isn’t like my church” variety. Croswell repeats a standard litany of anti-Catholic talking points; describes church rituals in a way designed to make them seem exotic and bizarre; slanders the character of the Mother Superior and the Bishop; and engages in Morse-style conspiracy mongering.

(In his defense, some of the rituals described in the book are pretty weird by modern standards. I’m pretty sure no on is forcing nuns to make the sign of the cross on the floor with their tongue as an act of contrition, at least not any more.)

From a Catholic standpoint, the annoying thing is that much of what is declared inexplicable is in fact perfectly explicable, if it wasn’t being described by someone both ignorant and incurious and an interlocutor attempting to cast things in the worst possible light. Here’s an example: at one point Rebecca is scolded for gargling before Communion, and thinks the other nuns are just being mean to her for no reason. Pretty much any Catholic could have told her that you’re not supposed to eat or drink anything before taking Communion. In fact, it’s something Rebecca herself would have known if she had been reading her Catechism. Which she wasn’t.

There are a few serious allegations in the book that do deserve attention. Most notably, even if Reed was supposed to be withdrawing from the material world she was only a postulant and not a nun, and the Mother Superior should not have been screwing with her correspondence.

At its core, Six Months in a Convent is the tale of a young girl forcing her way into an unfamiliar situation and getting frustrated that she is expected to conform to it rather than have it conform to her. The irony is that as a recent convert Rebecca Reed was actually given a lot of leeway by Mother St. George and Bishop Fenwick, and was allowed to make errors that would have never been tolerated from a life-long Catholic. When it became clear that Reed wasn’t improving, the Mother Superior and Bishop switched strategies and started treating her like any other postulant. Reed didn’t like that, and bailed almost immediately.

Six Months in a Convent sold 10,000 copies in its first week, and has sold more than 200,000 copies to date. That’s right, it’s still in circulation today, resurrected every decade or so by some group that gets an anti-Catholic bug up its butt and can’t be bothered to do basic fact-checking.

Not that Catholics didn’t try to fact-check the book. Mother St. George published her own book, An Answer to Six Months in a Convent, Exploring its Falsehoods and Manifold Absurdities. It’s mostly a page-by-page rebuttal of Rebecca Reed’s assertions, combined with a sharp-tongued attack on Reed’s personal character. It’s also dry as toast and not terribly interesting. Six Months in a Convent’s audience was reading so they could go on a rollercoaster emotional journey and make a concerned tut-tut every know and then. They weren’t interested in a reasoned discussion of theological points and an explanation of Catholic ritual.

Moffat’s book sold terribly, of course. Even two Protestant books rebutting her rebuttal sold better.

Ashes to Ashes, Dust to Dust

The real lesson of the burning of the convent is that it is very hard to counter emotion with intellect. You can tell the truth as clearly and directly as possible, but logic loses to emotion nine times out of ten. Someone gripped by paranoia and terror is not going to be settled by your polite reassurances. In the end Catholics and Protestants were talking two different languages, one of them high-minded, the other not, and this miscommunication led to a breakdown of trust and civic order.

On the first anniversary of the burning of the Convent, Protestants applied for a permit to parade through Charlestown carrying an effigy of Mother St. George that they would then shoot through the head and throw on a fire. For once the Charlestown selectmen were proactive instead reactive and denied their permit.

Over the next two decades attacks on Catholic churches in New England became so common that many congregations protected themselves with armed security guards 24/7. Of course, the presence of armed security guards angered Protestants, triggering more attacks, in a terrible vicious circle.

Rebecca Reed died of tuberculosis on February 28, 1838. It seems very likely she contracted the disease from one of her fellow postulants at the convent.

As for the Ursuline convent itself, well, it was a total loss. The Catholic Diocese of Boston estimated the damages at $100,000 (that’s about $3.2 million today) and tried to get reparations from the state. Friendly legislators introduced bills to compensate the diocese in 1835, 1846, 1853 and 1854 — and each time those bills were voted down by huge Protestant majorities. The people of Massachusetts clearly thought the burning was a tragedy, but well, it wasn’t their tragedy and they weren’t going to waste their money on it.

The diocese let the convent remain as-is as a rebuke to the city and state. The charred ruins were clearly visible for miles around, especially from the top of the new Bunker Hill Monument. In the 1870s the diocese finally sold the land to a railroad, who cleared the rubble, leveled the land to lay tracks, and subdivided the rest into lots for individual homes.

Today you’d never know it was ever there, except for a state historical marker.

Connections

In addition to being a noted anti-Catholic, Samuel F. Morse was also the inventor of the telegraph. Maybe. Dr. Charles Thomas Jackson claimed that Morse had stolen the idea, and the two men spent decades locked in pointless litigation. Dr. Jackson also claimed to have given William Morton the idea for surgical anesthesia (“Kings of Pain”).

Austrian prime minister Klemens von Metternich may or may not have been conspiring to take over America with an army of Bavarian Illuminists, but he most definitely refused to provide assistance to British diplomat Benjamin Bathurst (“Gone Guy”).

In 1834, Protestant activist Samuel B. Smith was chased through the streets of Baltimore by a Catholic mob. Smith would later go on to work with fake “escaped nun” Maria Monk (“The Awful Disclosures”).

The (entirely fake) legend of Borley Rectory (“The Fakiest Fake in England”) also featured a young nun being bricked up alive inside a convent’s walls.

After the convent was demolished, the Charlestown State Prison was eventually built on the site. One of its residents was bigamist George W. Pepper (“A Good Thing to Die By”).

Sources

- Anbinder, Tyler. Nativism & Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings & the Politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Archdeacon, Thomas J. Becoming American: An Ethnic History. New York: The Free Press, 1983.

- Billington, Ray Allen. The Protestant Crusade, 1800-1860. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1964.

- Blair, Jennifer. “Reading for Information in St. Ursula’s Convent, or The Nun of Canada.” The Yearbook of English Studies, Volume 46 (2016).

- Carey, Patrick W. “The Confessional and Ex-Catholic Priests in Nineteenth-Century Protestant America.” U.S. Catholic Historian, Volume 33, Number 3 (Summer 2015).

- Hofstadter, Richard. Anti-Intellectualism in American Life; The Paranoid Style in Amercan Politics; Uncollected Essays 1956-1965. New York: Library of AMerica, 2020.

- Mercado, Monica L. “Have You Ever Read? Imagining Women, Bibles and Religious Print in Ninteenth-Century America.” U.S. Catholic Historian, Volume 31, Number 3 (Summer 2013).

- Moffat, Mary Anne Ursua. An Answer to Six Months in a Convent, Exposing Its Falsehoods and Manifold Absurdities. Boston: James Monroe, 1835.

- Munroe, James Phinney. “The Destruction of the Convent at Charlestown, Massachusetts, 1834.” New England Magazine, February 1901.

- Myers, Gustavus. History of Bigotry in the United States. New York: Random House, 1943.

- Reed, Rebecca Theresa. Six Months in a Convent: A Narration of Facts. Boston: Russel, Odiome & Metcalf, 1835.

- Rugoff, Milton. The Beechers: An American Family in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Harper & Row, 1981.

- Schreiner, Samuel A. Jr. The Passionate Beechers: The Family Saga of Sacntity and Scandal that Changed America. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- Schultz, Nancy Lusignan (editor). Veil of Fear: Nineteenth Century Convent Tales by Rebecca Reed and Maria Monk. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 1999.

- Whitney, Louisa. The Burning of the Convent. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1877.

- Yacovazzi, Cassandra L. “Are You Allowed to Read the Bible in a Convent? Protestant Perspectives on the Catholic Approach to Scripture in Convent Narratives, 1830-1860.” U.S. Catholic Historian, Volume 31, Number 3 (Summer 2013).

- Yacovazzi, Cassandra L. Escaped Nuns: True Womanhood and the Campaign Against Convents in Antebellum America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- “Fire, outrage.” Boston Morning Post, 13 Aug 1834.

- “Threatened assassination.” Fall River Monitor, 30 Aug 1834.

- “Trial of the convent burners.” Boston Morning Post, 8 Dec 1834.

- “Miss Rebecca Theresa Reed.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 Mar 1835.

- “Impotent and impudent falsehood.” Greenfield Gazette & Franklin Herald, 31 Mar 1835.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: