Kings of Pain

who gets the credit for an important discovery?

To all those sufferers throughout the world, wHho, in their time of sorest need, have been relieved by the boon it has been the happy lot of the discoverer to confer, and have returned thanks for the priceless blessing, this [episode] is dedicated.

Since the dawn of medicine, surgeons have had to deal with one major problem: it turns out people don’t like it very much when you start cutting into their flesh. They start screaming and crying and thrashing about. It makes it damned difficult to get anything done.

The surgeons of antiquity had only one real way to deal with the problem: wine. Massive quantities of alcohol made patients groggy and sluggish, and therefore less able to fight back. That was a great help to the surgeons, though it didn’t actually do anything to lessen the pain felt by their patients. Well, unless they were so drunk that they passed out and became completely insensate. And if that were the case, it was very likely they might never wake up.

For centuries medical professionals searched for something that could help kill the pain, but nothing ever seemed to work out. Opium could make a patient languorous, but it was far to easy to deliver an underdose (in which case the patient would still feel everything) or an overdose (in which case the patient would die). Numbness could be introduced by tourniquets, but it wore off almost immediately. Leeching had the same problem, with the added bonus of introducing patients to shiny new leech-borne diseases. Extreme exsanguination could introduce sleepiness but only by taking the patients to the brink of death.

That’s where things stood for centuries. Millennia, even.

Factitious Airs

In the early 1770s, chemist Joseph Priestly discovered a number of “factitious airs” — that’s “synthetic gasses” for those of us who don’t speak old-timey English. Later in the decade physician Thomas Beddoes decided to review Priestly’s work and see if any of the factitious airs had potential medical applications.

Beddoes was too important to do the work himself, so he left the actual investigation to his assistant, some nobody named “Humphry Davy.” Working his way through the factitious airs, Davy reached one that Priestly called “dephlogisticated nitrous air” and started his rigorous testing protocol. Which is to say, he filled up a bladder with the stuff and then inhaled deeply from it.

Davy’s first important discovery was that dephlogisticated nitrous air wasn’t lethal. Well, at least not in the quantities he was huffing. His second important discovery was that was a mood enhancer. If Davy was energetic, it made him hyperactive; if he was relaxed, it made him sleepy; if he was happy, it made him exhilarated; if he was sad, it made him despondent. It also seemed to lower his inhibitions, make him laugh a lot, and remove his ability to feel pain.

In his notes, Davy gave dephlogisticated nitrous air a more manageable name, nitrous oxide, and wrote that “in its extensive operation [it] appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with advantage during surgical operations in which no great effusion of blood takes place.”

Beddoes took Davy’s notes and did… absolutely nothing with them. He was doctor, not a surgeon, and was only interested in factitious gases if they could cure diseases.

Laughing Gas

Nitrous oxide was not forgotten, though. Davy gave a few hits to his good friend, famous poet and drug addict Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who really liked how it made him feel. Word of the “laughing gas” and its mood-enhancing properties got around and it wasn’t long before chemistry students were doing whip-its in their dorm rooms.

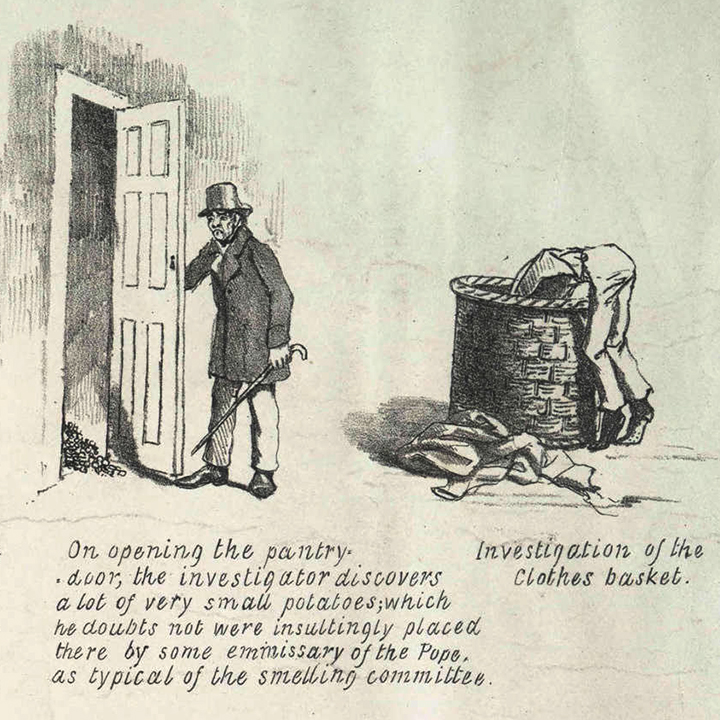

It took a few decades, but laughing gas parties eventually made their way out of the dorms and into the parlors of the well-to-do. They even became a part of public events, including scientific lectures, theatrical performances, and traveling medicine shows.

Enter Gardner Quincy Colton, a poor medical student from Vermont. In 1844 Colton had the bright idea of throwing a laughing gas party, charge a cover, and use his cut of the gate to pay for his tuition. His show was simple: he gave a brief lecture about the history of the gas, ran down its chemical properties, showed how it was made, and then let everyone in the audience take a hit. Everyone got nice and high, ran around like idiots for a while, and then sobered up and went home.

Colton’s first “Grand Exhibition of the Effects Produced by Inhaling Nitrous Oxide” was such a hit that he staged it several more times, then took it to Broadway, and then on a nationwide tour.

After the December 10th show in Hartford, Colton was approached by a patron who had watched several attendees injure themselves — except they were so high their injuries didn’t even register. The patron wondered out loud if laughing gas could be used to dull the pain of surgery, and asked Colton why no one had ever tried. Colton honestly replied that he had no idea. The patron then asked if he could buy some laughing gas, and Colton said sure. The next day the man came by the exhibition hall with a gas bag, which Colton graciously topped off.

And that’s how Horace Wells got his hands on a bag full of laughing gas.

Horace Wells was no ordinary thrill-seeker looking for a cheap high. He was one of Hartford’s most prominent dentists, a curious inventor with an eye for new devices and procedures that could make his job easier.

Now when it came to pain, dentists had it just as bad as surgeons. Possibly worse than surgeons, since the average surgical patient was unlikely to bite his doctor in a blind panic. If laughing gas could dull a patient’s pain sensations, that would be great. If it could preserve the integrity of Horace Wells’ fingers in the process, even better.

Wells immediately took the bag of laughing gas back to his office, inhaled the whole thing, and had his friend Dr. John Riggs extract a rotten tooth.

Wells didn’t feel a thing.

Within a few weeks Wells was manufacturing laughing gas at home and administering it to his own patients before procedures. “Painless dentistry” quickly made him the most popular dentist in Hartford. He hired multiple assistants to expand his practice, and even reached out an old friend, William Thomas Green Morton, about the possibility of opening a satellite clinic in Boston.

Morton had a flair for public relations, and he knew a good story when he heard one. He reached out to the doctors at Massachusetts General Hospital and told them about Wells’ discovery, thinking they would spread the word to their patients. The surgical department was very intrigued, and invited Wells to come talk about his procedure and demonstrate it on a surgical patient.

The lecture did not go well. Once the surgeons realized that Wells was using laughing gas they dismissed “painless dentistry” as a cheap parlor trick. The demonstration went even worse. The patient became drowsy and nodded off, but as soon as the surgeon made his first cut he woke up and started screaming. Wells was laughed out of the operating theater at Massachusetts General, and slunk back to Hartford in shame.

Wells had been lucky up to that point. He had been routinely underdosing his patients, giving them just enough gas to make them giddy but not enough to consistently make them immune to pain. Eventually he was going to run into a patient who needed a larger dose, and it was just his bad luck that it happened at the worst possible time.

Horace Wells took the loss so hard that he completely abandoned his dental practice. That may seem like an overreaction, but that’s just the kind of person Wells was. He plunged head-first into every new venture heedless of danger and full of boundless enthusiasm, only to plunge into abject despair the first time he encountered any setback.

Wells may have given up on dentistry, but dentistry didn’t give up on laughing gas. The effects didn’t last long enough to keep a patient under for a long surgery, but at the time the most complicated dental procedure consisted of little more a quick yank. Soon Wells was making a living by selling laughing gas to other dentists throughout Connecticut.

Hey, a fella’s gotta eat.

Sulfuric Ether

Horace Wells may have given up on his dream of painless dentistry, but his friend William Thomas Green Morton decided to pick up the ball and run with it.

William Morton was a colorful character, to say the least. His family was poor, and at an early age William had to drop out of school and go to work.

In 1836 Morton’s quest for work took him to Rochester, where he took a job at a dry goods store; joined “the Brick Church,” a new Protestant denomination popular with the town’s businessmen; and then sweet-talked fellow parishioner Loren Ames into being his partner in an import/export business. Ames provided the money, and Morton handled the day-to-day operations.

Those day-to-day operations involved purchasing goods from New York on Ames’ credit; selling those goods for a small profit and keeping all the revenue for himself; and cooking the books just in case Ames ever decided to check them. Morton was utterly shameless in his fraud. He began misrepresenting his business partner as Loren’s much wealthier older brother Lyman Ames, while the same time reorganizing the partnership structure in an attempt to completely freeze out Loren.

When the Ames brothers found out what Morton was up to they immediately dissolved the partnership. They were generous, though, and agreed to let bygones be bygones if Morton assumed all outstanding debts. Morton agreed, and then made no attempt to pay down any of those debts.

Within three months he was bankrupt. Another local businessman, Phineas B. Cook, agreed to “endorse” Morton’s debts for $5,000 on the condition that Cook would then take possession of the company’s remaining inventory. Morton took the cash, paid off his debts, sold off the inventory, and pocketed the proceeds for himself. When Cook protested, Morton dropped a bombshell: he was only seventeen years old, and therefore nothing he signed could be legally binding. It was a one-time get-out-of-jail-free card, and it worked. Mostly — he was expelled from the Brick Church for his scandalous conduct, for all that was worth.

In 1839, Morton brought his sister to Rochester and enrolled her in a fancy finishing school but neglected to pay her tuition. When the school threatened to drag the Mortons into court, he gave them a check for the entire amount drawn on a non-existent bank in Kentucky. By the time the school realized they’d been had, the Mortons were long gone.

In Cleveland, Morton got a job as a clerk, joined a Protestant church that was popular with the city’s businessmen, and sweet-talked fellow parishioner Charles Pomroy into partnering with him in an import/export business. Once that was set up Morton purchased goods on Pomroy’s credit and kept all the revenues for himself.

The added angle this time was that Morton fraudulently presented himself as a well-connected relative of the governor of Massachusetts, Marcus Morton. (No relation.) The young swindler became more audacious, and began forging checks and letters. He even got his hands on a set of official U.S. Mail seals he could used to create fake postmarks.

When Pomroy found out what his partner was up to, he dissolved the partnership and locked Morton out of the store. Morton then picked the lock and sold off the remaining inventory. Then he skipped town, leaving his creditors high and dry.

(One of those creditors was Cleveland’s top mohel. As his debts mounted, Morton had undergone a circumcision as part of an attempt to woo the beautiful daughter of a wealthy Jewish businessmen. When he skipped town he still owed the mohel $75 for the operation. At least the mohel got to keep the tip.)

This time Morton relocated to St. Louis. I’ll give you three guesses what happened next (the first two don’t count). The twist this time was that he tricked mark J.B. Sickles with a forged letter of introduction from a “mutual acquaintance.”

Afterwards Morton returned to St. Louis, apparently thinking he would be protected by girlfriend’s wealthy father and his social connections. It didn’t work. Irate creditors published an article in the St. Louis Daily Evening Gazette exposing Morton as a sham, and the young fraudster skipped town and headed back east.

Morton’s luck turned in Baltimore. Before he could hook a mark his stolen postal stamps and forged checks were discovered, and Morton was forced to flee town only a few steps ahead of John Law.

By the age of twenty one, William Thomas Green Morton had run out of four major American cities on a rail. He seemed destined for a life of crime… but that all changed in 1840 when he befriended Horace Wells.

Morton was looking for more stability in his life, and Wells thought dentistry could provide that stability. It was a well-paid, respectable profession… and even better, one that didn’t require much in the way of education or training.

Which was good because Morton was a bit of an idiot.

Wells made Morton his apprentice, and not long after that, his business partner. He set Morton up with a small practice in nearby Farmington with the understanding that he would eventually be reimbursed for the training and capital he provided. He never was, of course.

Then, Wells came up with a remarkable invention: a sort of dental solder that could be used to weld fake teeth to golden dental plates. He and Morton formed a partnership to manufacture them. Wells even paid one of the most eminent chemists in the country to endorse them. Dr. Charles Thomas Jackson did so gladly, because the money was good and his tests showed the solder worked as advertised.

There was only one problem: the dental plates were so expensive to manufacture that there was no way to make a profit off of them. (That’s probably why we don’t make them out of gold any more.) Wells, as usual, had rushed heedlessly into the manufacturing business without doing more research, and now he was quitting at the first sign of trouble.

Maybe the second sign of trouble. He also discovered that his business partner was bringing absolutely nothing to the table. Morton hadn’t invented anything, hadn’t contributed any funds to te partnership, and hadn’t even done any work to promote the product. The only thing he had been doing was draining Wells’s capital with his expense account.

The manufacturing partnership was dissolved, but the two men remained friends and continued to operate their joint dental clinics. Wells was too kind and forgiving for his own good… but at least he made sure all of his future transactions with Morton were notarized. He was soft-hearted, but he wasn’t stupid.

Flush with cash stolen from Wells, Morton did two big things. First, he moved his clinic from rinky-dink Farmington into big, bustling Boston. Second, he pitched woo to a wealthy patient, Elizabeth Whitman. Soon the pretty young woman was head-over-heels in love with her handsome dentist.

Elizabeth’s father, Edward, did not approve of his daughter marrying a mere dentist. He only consented to their marriage when Morton agreed to become a doctor. William and Elizabeth were wed in 1844, and shortly afterwards the couple moved in with Dr. Charles Thomas Jackson so that the eminent scientist could provide remedial instruction to the young dentist.

Morton eventually moved out and enrolled in Harvard Medical School, but never attended a single lecture. He had a panic attack when he realized that he wasn’t smart enough to be a doctor. Eventually he realized that his father-in-law’s ultimatum was nothing more than hot air, and there would be no repercussions for his failure. After that he could sleep well at night.

In 1845, Horace Wells shared the discovery of painless dentistry with his former apprentice. In turn, Morton shared the discovery with the doctors of Massachusetts General Hospital and got his old friend an invitation to demonstrate the new discovery. It’s highly likely that while Wells was being laughed out of the operating theater, Morton was sitting in the back row of the audience trying not to be noticed.

Wells quit dentistry after that fiasco, but Morton thought his friend had the right idea but the wrong gas. He began his own experiments, and eventually came across sulfuric ether.

The existence of sulfuric ether had been known for centuries; in the 16th Century, German doctor Valerius Cordus synthesized “sweet oil of vitriol” by mixing sulfuric acid and alcohol. Ether fumes worked a lot like nitrous oxide, but the effects were longer lasting and more potent. So potent, in fact, that chemists making ether would frequently pass out. In a laboratory that could be lethal, which earned the gas a dangerous reputation. In spite of that, it had become a popular party drug for chemistry students.

Morton conducted a few “experimental trials” on himself to determine the right quantity of ether to use. Once he worke everything out to his satisfaction, Morton attempted to conduct human trials on his in-laws — who quite sensibly refused. Morton was forced to do animal trials on the family dog, and only after those were successful could he convince a friend to undergo the process.

On September 30th, 1846, Morton invited a newspaper reporter into his office to witness the use of sulfuric ether on a dental patient. As the reporter watched, Morton knocked out his first patient of the day and extracted his rotten tooth. The patient didn’t even twitch during the procedure.

When the patient woke up minutes later, Morton playfully asked if he was to have his tooth extracted. The confused patient said yes, so Morton made a grand sweep of his arms, pointed to the tooth lying on the floor, and declared, “Well, it is now!”

If this sounds overly dramatic, it was. The whole scene was staged. The patient really did get a tooth removed, but he wasn’t some rando off the street. He was one of Morton’s close personal friends. For that matter, so was the reporter.

The cheap showmanship worked, though. After the article ran business picked up at the clinic. As the weeks wore on, Morton upped the razzle-dazzle factor, adding orange essence to mask the awful smell of sulfuric ether and changing the method of administration from a grubby ether-soaked rag to a complicated gas flow regulator of his own design. Or rather, which he paid his former landlord and teacher Dr. Charles Thomas Jackson to design.

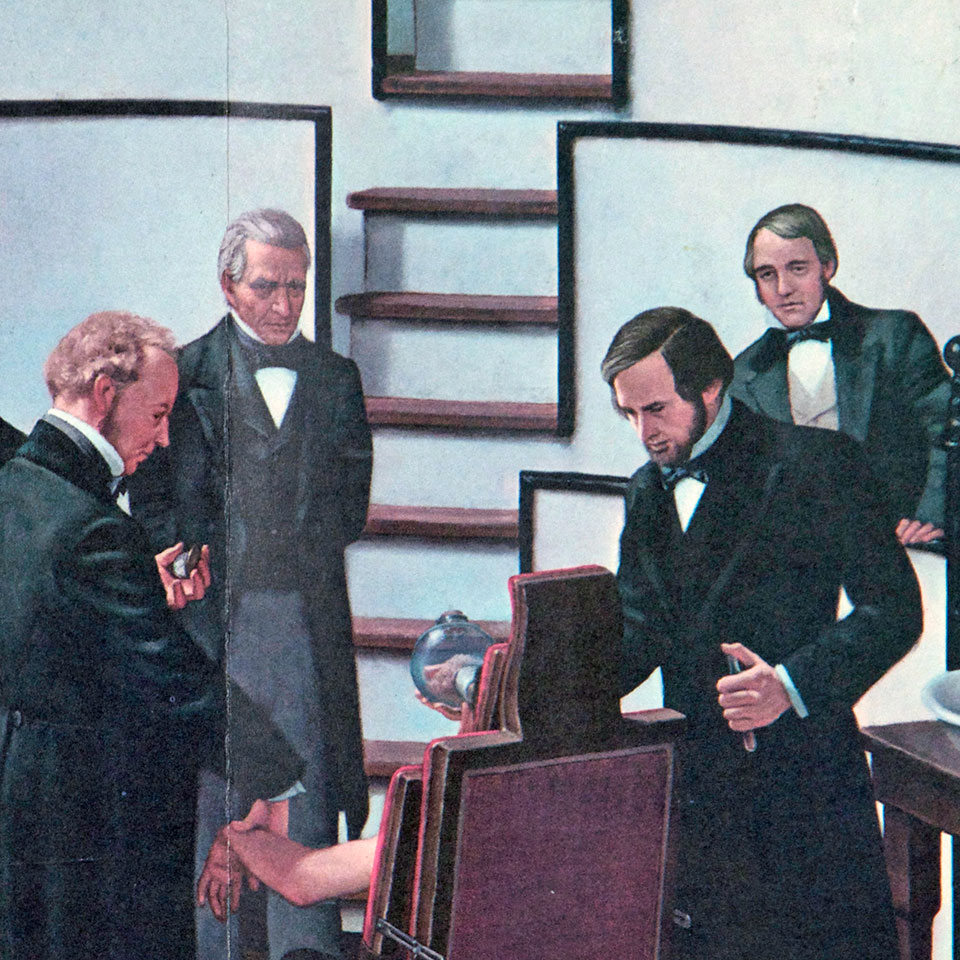

Word of Morton’s painless dentistry made it back to Massachusetts General Hospital, and the surgeons invited Morton to come demonstrate his process. Mindful of what had happened to Wells, a panicked Morton sat up all night tinkering with his gas flow regulator, trying to resolve some pesky technical problems. He eventually worked them them out, and on October 16, 1846 at 10:30 AM he burst into the operating theater a half hour late, right as the surgeons were about to start operating without him.

Morton quickly set up his new apparatus and put the patient under. The surgeons were then removed a large cancerous tumor from his neck, without so much as a twitch.

William Morton had succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. An account of the event was written up in the next issue of Scientific American. Soon Morton was the most successful dentist in Boston, hiring a small army of assistants to perform a dozen etherizations per day. He made moves to trademark patent his discovery, and even formed a company to distribute and market it nationwide.

Of course, to trademark a product you need a trade name. Morton assembled a “brain trust” of Boston’s top scientific and legal minds to come up with a trade name. The group included notables like zoologist Augustus Gould, surgeon Henry Bigelow, and geologist Louis Aggasiz, but it was jurist Oliver Wendall Holmes who suggested that “anaesthesia” had a nice ring to it.

Morton hated the name, and went with his first choice, “Letheon,” instead.

Morton also invited Horace Wells to visit him in Boston, observe an etherization, and invest in the Letheon Company. Wells, who only half-grasped what Morton was doing, refused. Back home in Hartford, Elizabeth Wells asked her husband if his former apprentice had actually discovered something new. Horace replied, “No! It is my old discovery, and he does not know how to use it.” He thought Morton was going to kill someone.

The move to patent Letheon was controversial. At the time, most doctors felt that it was unethical to patent medical breakthroughs, that profiting off disease and suffering was a violation of the Hippocratic oath. Morton wasn’t a doctor, had never taken the oath, and didn’t care about ethics in any case. If a doctor wanted to dismiss Letheon as mere patent medicine, well, Morton was happy to sell to a doctor down the street with fewer scruples.

Unfortunately, the largest group of holdouts were the surgeons of Massachusetts General. They refused to use Letheon unless Morton told them exactly what was in it. Morton resisted for a few weeks, but caved after his attorneys pointed out he needed the endorsement of the hospital more than the hospital needed Letheon. Morton was forced to admit that it was only sulfuric ether with hint of orange essence to improve the smell. The surgeons had suspected it all along, but now that their questions were answered they began using Letheon on their patients and talking up the product to every other surgeon who would listen.

It wasn’t all sunshine and roses for Morton, though. His former teacher, Dr. Charles Thomas Jackson, had begun claiming that it was he who deserved sole credit for the invention of Letheon.

This was confusing. Dr. Jackson had said nothing for weeks, even as Morton’s fame grew. Morton had paid Jackson a generous $500 consulting fee for assisting in the design of the gas flow regulator, and they had both agreed that it was more than adequate recompense for the services rendered. Morton had even offered to give the doctor a 10% stake in his patent and Jackson had refused, citing his professional ethics, until his attorney advised him to sign on to the patent application.

Clearly, something had changed over the previous few weeks. But what?

The Ether Wars (Part 1)

To understand that, we’ll have to take a look at Dr. Charles Thomas Jackson.

As a child, Jackson developed a keen interest in the natural sciences. At the time, Boston society didn’t consider science to be a respectable profession for a young brahmin. That bias was shared by Jackson’s father, who insisted that his only son would go into a respectable profession — medicine. He even managed to enforce that desire from beyond the grave by making Charles’s inheritance conditional on his graduation from medical school.

Jackson and his sisters conspired to come up with a clever workaround that made make everyone happy. Jackson did attend Harvard Medical School and graduated in 1829, but then he traveled to Paris for post-graduate studies at the University of France. Without the will’s executor constantly looking over his shoulder, Jackson was able to pursue independent studies in other sciences on the side. He received advanced degrees in medicine and geology before returning to the United States in 1832.

Jackson was in unusually high spirits on during the return voyage and entertained his fellow passengers with intelligent conversation about the scientific discoveries of the day. (It turns out he was a bit of a know-it-all, which I think we can all appreciate.) One evening the topic of conversation turned to electricity, and as usual Jackson had a lot to say about the matter. That piqued the interest of another passenger, a young painter returning from a Grand Tour of Europe. He peppered Jackson with questions all evening… and then the following day… and then the day after that.

The newly minted Dr. Jackson claimed his inheritance and became financially secure. He never practiced medicine and became a geologist instead, conducting mineral surveys throughout the Northwest Territory for the federal government, and serving at various times as the state geologist of Maine, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire.

In 1837, Jackson received a letter from the painter with whom he had conversed on his voyage home. Samuel Finley Breese Morse had been mulling over those shipboard conversations for years. He had developed a working electric telegraph system, and was finally ready to apply for a patent. He was looking for witnesses who could back up his claim to have independently invented the device.

The response he received from Dr. Jackson stunned him. Jackson pointed out that the telegraph was based on ideas that the two men had discussed. Morse didn’t dispute that, but Jackson then went on then argued that since Morse had no knowledge of electricity at the time, those ideas were all Jackson’s. He demanded that Morse acknowledge him as the sole inventor of the telegraph.

Now, it is undeniable that Jackson had provided the basic principles of electric telegraphy to Morse, but he was hardly the first to work them out. Ampère and Sömmerring had already built crude versions of the device, and more refined systems were had been developed by Gauss and Wheatstone. It could be argued that Jackson did deserve some share of the credit, but the lion’s share? Hardly. In any case, Morse was in no mood to share any of the credit. He told Jackson to stuff it.

Jackson did not stuff it. He sued.

Morse’s position is easy to understand. Jackson may have given him some ideas, but Morse was the one who had turned those ideas into reality. His telegraph was the result of years of independent experimentation, and moreover relied on technologies that had not exited at the time of his conversations with Jackson.

Jackson’s position is harder to understand at first, especially since he didn’t seem to care about the money at all. Deep down, though, it boiled down to one thing: it wasn’t enough for him to be a scientist. He had to be a great scientist, the discoverer of some fundamental principle or the inventor of some incredible device. Something, anything, that would prove to the ghost of his father that he was right to abandon medicine for geology.

The ensuing court battle between Jackson and Morse lasted for decades, and their behavior spoke poorly to both men’s character. They were revealed to be petty, stubborn, vain, and vindictive.

Dr. Jackson’s case was awfully weak, and it did not help that he tried to bolster it with transparent lies. He claimed to have corresponded or met with Morse on several occasions — but he hadn’t. Morse had written to him, and Jackson had never answered. Jackson even claimed that he had built a working telegraph of his own in 1834 but had never bothered to write about it for any journals or even bother show it to any of his friends. He would have been laughed out of court if it weren’t for the zealous advocacy of his brother-in-law, some guy named “Ralph Waldo Emerson,” and an obscure family friend named “Henry David Thoreau.”

Morse could have easily prevailed on the merits, but decided that he would rather win by dragging his opponent through the mud. He claimed Jackson suffered from “excessive vanity, partial insanity, and a reckless disregard of truth and justice.” He claimeds that Jackson plagiarized large chunks of his geological surveys from Canadian sources, and that he had also attempted to steal the credit for inventing guncotton from Christian Friedrich Schönbein. Neither claim was true. Jackson’s geological surveys were similar to existing surveys because they were surveying the same country. He had managed to get an article about guncotton published before Schönbein’s discovery was public knowledge but never claimed that he was the inventor.

In 1846, as Dr. Jackson was battling Morse in the courts, William Thomas Green Morton dropped by one day to borrow the old gas bag’s, uh, gas bag. Jackson wanted to know why his one-time pupil and tenant needed a gas bag, since Morton was a thick-o with no interest in chemistry. Morton responsed that he was going see if he could use the placebo effect to get results similar to the ones his friend Horace Wells had been achieving with nitrous oxide.

Dr. Jackson was horrified. He told Morton it was a terrible idea. Then he proposed an alternative: sulfuric ether.

Jackson had previous experience with ether and its effects. While work in his lab in 1832, Jackson inhaled a lungful of chlorine gas and began choking. Remembering from medical school that sulfuric ether could be prescribed for breathing difficulty, he huffed some fumes to soothe his irritated throat. Soon he was high as a kite, and insensible to pain. He’d been meaning to do something with that discovery, but had never got around to it.

Now he freely offered it up to Morton. At least this way the young idiot wouldn’t kill someone. Morton, who had never even heard of sulfuric ether before this point, thanked Jackson for the tip and went on his merry way.

I think you know what happened after that.

At first Jackson was happy to let Morton take the credit for the invention of Letheon, but as the weeks went on and the young dentist became the toast of the town that opinion began to change. It was the Samuel Morse situation all over again, only worse because at least Morse had dome some hard work to develop a working telegraph from Jackson’s designs. The only thing Morton had contributed to Letheon was adding some perfume to mask the smell.

Morton did offer Dr. Jackson a share of the patent, but not out of generosity. It was an attempt to buy off the old man so that he wouldn’t get in the way of the patent application. Morton and his lawyers hoped that small sop would satisfy the old grump. They had no such luck.

The court battle between Jackson and Morton lasted for decades, and their behavior spoke poorly to both men’s character. The Ether Wars had begun.

William Morton pled his case in the popular press, wining and dining reporters up and down the Eastern seaboard and writing books that promoted a folksy and enchanting, if entirely untrue, story about how he discovered of sulfuric ether and arguing that he deserved sole credit for the way it was revolutionizing surgery.

Dr. Charles Jackson pled his case in the scientific community, writing letters to the French Academy of Sciences and promoting his own exaggerated stories of how he bestowed the knowledge of sulfuric ether upon a complete ignoramus, and arguing that he deserved sole credit for the way it was revolutionizing surgery.

Horace Wells even crawled out of the woodwork insisting that he was the first person to come up with the idea of inhaled anesthesia, even if he had the wrong gas, and arguing that he deserved sole credit for the way it was revolutionizing surgery.

It was all very, very confusing and no one could quite figure out who actually deserved the credit. Actually, let me walk that back. No one seemed to think Horace Wells deserved the credit except for the state legislature of Connecticut, who were determined that the glory belonged to their fellow Connecticutensian.

Morton joined forces with Morse to open up a second front in the ongoing assassination of Jackson’s character. They portrayed their opponent as a serial thief of ideas, a plagiarizer, a pathological liar, a drunk, a has-been who hd washed out of medicine.

Determined not to make the same mistakes he was making with Morse, Jackson lowered himself to Morton’s level. He exposed the dentist’s criminal past and called him a con artist, a grifter, and an all-around idiot.

The irony was that the two men were battling over the credit for a commercial failure. Once word got out that the Letheon was nothing more than readily available sulfuric ether, dentists and surgeons stopped paying for Morton’s expensive subscription service and started making it for themselves. The only thing Morton had to offer over the generic brand was his gas flow regulator, which was so poorly designed and cumbersome to use that no one bothered. It was easier and just as precise to use an ether-soaked sponge.

And that’s when they were were using sulfuric ether at all. For several years its use in the United States was localized to New England, because Morton’s patent application had convinced doctors further away that Letheon was mere patent medicine, no more effective than the snake oil they could get from the local quacks.

To try and salvage what was left of his business, Morton offered to sell Letheon to the Army and Navy at a bulk discount. It seemed like a slam dunk, especially since the country was in the middle of the Mexican-American War and field surgeons were busier than ever. In the end, though, the armed forces declined… because they were already using the generic brand.

By the end of 1847, the Letheon Company was bankrupt. Morton’s dental clinics also went under when his assistants quit en masse to open their own clinics. It didn’t help that Morton was in charge of the finances at both companies, and while he knew how to cook the books he apparently had no idea how to keep them.

Morton was forced to retire to a life of genteel poverty in the country. Well, at least, that’s how he portrayed it. In truth, he was living on a lavish estate, “Etherton Cottage,” paid for by his wife Elizabeth’s family money.

These setbacks might have induced a less stubborn man to give up the fight. Not Morton, though: he fought harder than ever. His plan was now to claim sole credit for the invention of anesthesia, and then somehow convince the government to give him a huge honorarium for the service he had rendered to mankind.

Morton’s newfound resolve also steeled the resolve of his opponents. If there was money at stake, well, Horace Wells wanted his fair share. Jackson didn’t care about the money at all, but he would be damned if he let an idiot steal his glory.

Chloroform

As the three men battled it out in the courts of law and public opinion, a new miracle gas appeared on the scene: chloroform.

Like nitrous oxide and sulfuric either, chloroform had been around for years. In recent years British scientists had noticed its anesthetic properties, and after the start of the Ether Wars they began to look the substance in a new light. Chloroform’s number one fan was obstetrician James Young Simpson, who had first discovered its properties after huffing a big bag full of it at a party.

As an anesthetic, chloroform had major advantages over its rivals. It was fast acting, powerful, and cheaper to make. It also wasn’t combustible, which was important in those days when indoor light was provided by open flames. Of course, it was also extremely lethal if you accidentally administered an overdose, but no one considered that a drawback because surgery was already lethal enough.

It wasn’t long before chloroform had displaced ether as the anesthetic of choice. One of its earliest fans in America was Horace Wells. He wasn’t using it on his dental patients, though. No, he was using it to get high.

After abandoning his dental clinic and his family, Wells had relocated to New York and taken up residence in the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Tribeca. He lived on the edge of development, on a run-down street frequented by ruffians and prostitutes. As an addict, Wells fit in just fine.

One day of Wells’s rough new friends asked him to whip up a bottle of vitriol. At the time, splashing those who had spurned your affections with vitriol was a popular past time, though it sounds a lot less charming once you know that “vitriol” is sulfuric acid. Anyway, Wells agreed, they doused an ex-lover or two with the stuff, and had a good laugh. Then the friend asked Wells to whip up more so they could “continue the sport.” Wells did, but then thought better of it and refused. The bottle remained on his mantle, though.

On January 20th, 1848 Wells went back to his apartment and got high. He was out for a few hours, but awoke in a frenzy, grabbed the bottle of vitriol, and ran up and down Broadway splashing it on every woman he saw. Several were burned, one so severely she was sent to the hospital. The women ran to the police, identified Wells as the monster behind the attacks, and he was quickly arrested.

Wells didn’t seem to realize the seriousness of his predicament until about halfway through his January 23rd arraignment. Afterwards he was returned to his cell in the Tombs. There he took a bottle of chloroform out of his boot, got high, and opened his femoral artery with a straight razor hidden in his other boot. As Wells bled to death on the cold stone floor he wrote a self-pitying letter to his wife and children begging for forgiveness… and still stumping for his fair share of credit.

I again take up my pen to finish what I have to say. Great God has it come to this? Is it not all a dream? Before 12 tonight to pay the debt of Nature; yes, If I were to go free tomorrow I could not live and be called a villain. Got knows I am not one… I die this night believing that God, who knoweth all hearts, will forgive the dreadful act. I shall spend my remaining time in prayer. Oh what misery I shall bring on all my near relatives, and what still more distresses me is the fact that my name is familiar to the whole scientific world as being connected with an important discovery. And now, while I am scarcely able to hold my pen, I must to all say farewell! My God forgive me! Oh my dear wife and child, whom I leave destitute of the means of support, I would still live and work for you, but I cannot. Did I live I should become a maniac.

suicide note of Horace Wells

If you are tempted to shed a tear for Horace Wells, you should remember that most drugs don’t put violent ideas in your head. What they do is lower your inhibitions, making you more likely to do things you were already inclined to do. Chloroform didn’t make Horace Wells want to attack women, it only made it easier for him to acknowledge that he wanted to attack women.

The Ether Wars (Part 2)

Wells may have been out of the picture, but Morton and Jackson were still going at it hammer and tongs.

Each man had a small coterie of true believers to plead their case. Jackson could always rely on the support of Emerson and Thoreau. Morton had somehow managed to get Daniel Webster on his team. Even dead Horace Wells had plastic surgeon Dr. Thomas Dent Mütter stumping for him.

The only thing they wound up accomplishing was destroying each other’s reputations. Morton had always been a money-grubbing liar and a cheat, and thanks to Jackson the whole world knew it. Jackson had always been obsessed with fame and glory and scornful of lesser men, but it took Morton to reveal that to the world.

Increasingly, the general public did not care for either man. Nobody wanted to give either one of them the credit, and they certainly weren’t interested in handing out any large cash prizes.

In 1850 the French Academy of Sciences attempted to use the wisdom of Solomon to broker an end to the Ether Wars. The Academy had initially been inclined to award the honor to Jackson, a fellow scientist known to many of its members, but were troubled by his recent behavior. It was also not inclined to award the honor to Morton because of his unethical attempt to patent a medical discovery. In the end the Academy decided to split the difference and recognize both men as the inventors of anesthesia. They each received a gold medallion and a small cash reward.

The decision satisfied neither man. They quickly went back to sniping at each other, but they were locked in a stalemate.

Then, in 1854, Jackson dragged another combatant into the Ether Wars. Crawford Long was a graduate of Transylvania University and the University of Pennsylvania medical school, now working as a country doctor in rural Georgia. Three years after Morton’s first public demonstration of surgical ether, Long wrote an article for the Southern Medical Journal claiming to have used sulfuric ether in a series of operations dating back to 1842.

Now, at first glance Long’s claims feel a bit like a bit of backwoods braggadocio. “Oh, sure, down in Georgia we used to use ether all the time, just never though there was anything about it worth mentioning.” There were dozens of other doctors who had made similar claims over the years. What set Long apart, though, was that his claims were documented. He had receipts and other records that backed up his version of events.

Now, you might think that Charles Jackson would be poorly disposed towards Crawford Long, since Long’s story undermined his own claim to be the sole discoverer of anesthesia. After the Academy’s decision, though, Jackson’s priorities had shifted. He did not want to win as much as he wanted William Morton to lose. To that extend, he started pushing Long as the co-discoverer of anesthesia.

Long did nothing to tip the balance of power, however, and the Ether Wars remained a stalemate. It turns out no one cared any more. The public had moved on, and desperately wished both men would do the same.

For one shining moment the Civil War seemed to turn Morton’s fortunes around, when the Surgeon General recommended that he receive a special award for his discovery of anesthesia. Congress was slow to act on the recommendation, though, and then Morton’s case was finally dealt a fatal blow.

For years Morton had been scraping by as a patent troll, suing doctors who used sulfuric ether as an anesthetic and settling with them out of court. One clinic, though, was brave enough to pursue a judgment and get the entire patent invalidated, on the principle that you can’t patent a substance. The decision was savage.

In a naked ordinary sense, a discovery is not patentable. A discovery of a new principle, force, or law, operating or which can be made to operate on matter, will not entitle the discoverer to a patent. It is only where the explorer has gone beyond the mere domain of discovery, and has laid hold of the new principle, force, or law, and connected it with some particular medium or mechanical contrivance, by which, or through which, it acts on the material world, that he can secure the exclusive control of it under the patent laws…

A discovery may be brilliant and useful, and not patentable. No matter through what long, solitary vigils, or by what importunate efforts, the secret may have been wrung from the bosom of nature, or to what useful purposes it may be applied. Something more is necessary. The new force or principle brought to light must be embodied and set to work, and can be patented only in connection or combination with the means by which, or the medium through which, it operates. Neither the natural functions of an animal upon which, or through which, it may be designed to operate, nor any of useful purposes to which it may be applied, can form any essential parts of the combination, however they may illustrate and establish its usefulness.

Morton v. New York Eye Infirmary (17 F. 879, 1862 Dec 01)

That was it for Morton. No one was going to give him a red cent now. His “momentous discovery” was now “obvious” and “unpatentable.” Still he fought on, making one final attempt to plead his case in 1868. During the New York leg of the trip he fell ill. On July 15, Morton was riding in his carriage when he began screaming at the top of his lungs. Then he burst out of the carriage and dashed into Central Park, where he dunked his entire head into the waters of a nearby pond. His traveling companions pulled him out of the water and rushed him to the nearest hospital, where he was pronounced dead of “congestion of the brain” brought on by sunstroke.

Jackson continued to press his own case after Morton’s death. It didn’t work. People had always thought he was disagreeable, and now they thought he was classless for libeling a dead man. With everyone seemingly against him Jackson became paranoid and defensive, which made everyone actually against him. In 1873 Jackson fell down the stairs after a stroke and could no longer speak intelligibly. He spent the rest of his life in an asylum and died in 1888.

The Judgment of Posterity

With all of its combatants dead and gone, the Ether Wars finally came to an end. Even so, the question remained: who deserved the credit?

At first posterity seemed to favor William Thomas Green Morton. This seems to be a side effect of how both men pled their case. Morton argued his side through books and pamphlets that were widely read, while Jackson argued his side through private correspondence and legal memoranda that were seldom seen.

That would have been understandable enough, if Morton’s proponents hadn’t also been dead set on making him a martyr and Jackson a monster. Most accounts portrayed Morton as a selfless humanitarian hounded to an early grave by a vindictive associate. Jackson was even given an ironic comeuppance, as they insisted his final years in the asylum were not due to his need for convalescent care but due to “madness” brought on by the sight of the monument erected in Morton’s honor. This version of the story received its ultimate expression in the 1944 Preston Sturges film The Great Moment. Morton is played as portrayed as a virtual saint, while Jackson is played as a mean drunk sneering lines like “Go back to your tooth-yanking and leave science to the scientists.” Amazingly, though the plot is centered on the battle between both men, the film provides no context whatsoever to help explain what’s going on.

In more recent years, though, the Ether Wars have received a long overdue critical re-examination.

So ask yourself this: who deserves the credit for the discovery of anesthesia? Was it William Morton, who actually performed the first etherization? Was it Charles Jackson, who provided Morton with all the necessary knowledge? Why not Horace Wells, who gave him idea in the first place? Why not Gardner Colton, who introduced Wells to laughing gas? Why not Crawford Long, who beat them all to the punch? Why not Humpry Davy, who first noted the anesthetic properties of nitrous oxide? Why not Thomas Beddoes, who was Davy’s boss? Why not Joseph Priestly, who discovered nitrous oxide in the first place? Why not Valerius Cordus? You could easily construct a case for any of them.

Now take a step back and realize that you’re framing the argument in the wrong way.

In history, there are two conflicting school of thought: the “great man” theory which argues that all developments are the result of decisions made by extraordinary individuals, and the “trends and forces” theory that argues that all developments are the result of societal pressures far greater than any one person. The truth, of course, is probably a bit more complicated, with trends and forces often given a good shove in the right direction by a great man, but like it or not the trends and forces are often more important than the individuals involved.

As with Morse and the telegraph, multiple groups of people were simultaneously closing in on the idea of surgical anesthesia. Someone was going to get there first… but does that person deserve sole credit for the discovery?

The short answer to the question is that everyone listed above deserves the credit for discovering anesthesia, and the same time none of them do. There can be no one discovery of anesthesia, because the discovery anesthesia is not a singular event but the culmination of years of science and observation.

This isn’t a novel argument. It was first made in the waning days of the Ether Wars, in an obituary of Charles Thomas Jackson that ran in The Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The discovery of anesthesia, like the discovery of printing, was too great a gift for any one man to confer on his race… That Doctor Jackson suggested the use of ether for producing insensibility to pain, and that this suggestion was based on previous experience, seems unquestionable. But it was not a suggestion, however fruitful; not an unimproved experience, however important; not a rash experiment, though called courageous when successful: but the careful and cautious investigation of the conditions of success and the limits of safety, that constituted the great gift for which mankind should be grateful. The monument erected on the Public Garden in Boston, in honor of the discovery of anesthesia, by blazoning no man’s name, implicitly records the verdict in which most thinking men acquiesce; and the one great lesson which the “Ether Controversy” should teach is that for such great gifts, not to man, but to God, belongs all the glory.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Volume 16

Connections

One of the members of Morton’s “brain trust” was geologist Louis Agassiz. Many things have been named in honor of Agassiz, most notably Lake Agassiz, a glacial lake in the central plains of the United States and Canada that dried up in the early Pleistocene era. That hasn’t stopped pseudo-historians from speculating that the lake somehow survived into early modern times and was used by Vikings to reach central Minnesota (“Westward Huss”).

In addition to being an inventor, Samuel F. Morse was also a noted anti-Catholic bigot (“The Awful Disclosures”).

In his later years, Charles Thomas Jackson suffered from paranoid delusions that a cabal of Harvard professors that was conspiring against him. The purported leader of this group? Eben Norton Horsford, best known as the inventor of baking powder, but who you might remember for his unshakeable conviction that Boston was the site of the lost (and completely fictional) Viking colony of Norumbega (“Westward Huss”).

Sources

- Archer, W. Harry. “Chronological History of Horace Wells, Discoverer of Anesthesia.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Volume 7, Number 10 (December 1939).

- Beecher, Henry K and Ford, Charlotte. “Some New Letters of Horace Wells Concerning an Historic Partnership.” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Volume 9, Number 1 (January 1954).

- Bigelow, Henry J. Ether and Chloroform: A Compendium of their History, Surgical Use, Dangers, and Discovery. Boston: David Clapp, 1848.

- Boland, Frank K. “Crawford Long and the Discovery of Anesthesia.” The Georgia Review, Volume 6, Number 1 (Spring 1952).

- de Camp, L. Sprague. The Fringe of the Unknown. Buffalo, NY: Prometheus Books, 1983.

- Fenster, Julie M. Ether Day: The Strange Tale of America’s Greatest Medical Discovery and the Haunted Men Who Made It. New York: HarperCollins, 2001.

- Gay, Martin. A Statement of the Claims of Charles T. Jackson, M.D. to the Discovery of the Applicability of Sulphuric Ether in Surgical Operations. Boston: David Clapp, 1847.

- Gerald, Michael C. “Drugs and Alcohol Go to Hollywood.” Pharmacy in History, Volume 48, Number 3 (2006).

- The Invention of Anaesthetic Inhalation. New York: D. Appleton, 1880.

- Morton, William Thomas Green. Discovery of Etherization: Brief Embracing the Legal Points of Dr. Morton’s Case. Self-published, @1850.

- Morton, William J. Memoranda Relating to the Discovery of Surgical Anesthesia, and Dr. William T.G. Morton’s Relation To This Event. New York: self-published, 1905.

- Rice, Nathan P. Trials of a Public Benefactor. New York: Pudney & Russell, 1859.

- Silverman, Kenneth. Lightning Man: The Accursed Life of Samuel F.B. Morse. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003.

- Sims, J. Marion, et. al. “On the Nitrous Oxide Gas as an Anaesthetic.” British Medical Journal, Volume 1, Number 380 (April 11, 1868).

- Smith, Truman. An Inquiry into the Origin of Modern Anaesthesia. Hartford: Brown adn Gross, 1867.

- Soifer, Max E. “Historical Notes on Horace Wells.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Volume 9, Number 1 (January 1941).

- Sturges, Preston. The Great Moment. Hollywood, CA: Paramount, 1944.

- Wolfe, Richard J. Tarnished Idol: William T. G. Morton and the Introduction of Surgical Anesthesia. San Anselmo, CA: Norman Publishing, 2001.

- Wolfe, Richard J. and Menczer, Leonard E. I Awaken to Glory: Essays Celebrating the Sesquicentennial of the Discovery of Anesthesia by Horace Wells. Canton, MA: Science History Publications, 1994.

- Wolfe, Richard J. and Patterson, Richard. Charles Thomas Jackson: “The Head Behind the Hands.” Novato, CA: HistoryOfScience.com, 2007.

- “Charles Thomas Jackson” Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Volume 16 (1881).

- “Suicide of Dr. Horace Wells of Hartford, Connecticut, U.S.” Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal (1844-1852), Volumne 12, Number 11 (May 31, 1848).

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: