Monster without a Mask

the life and times of Rondo Hatton (1894-1946)

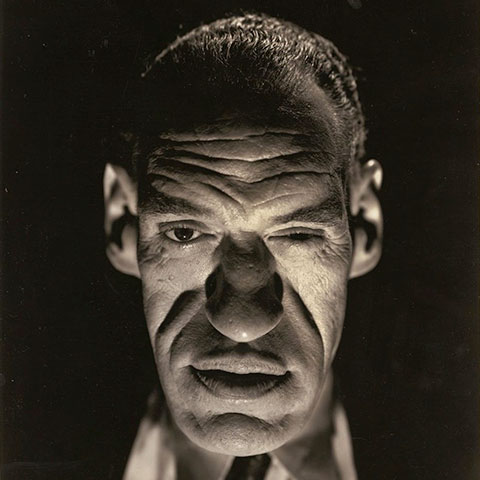

They called the Glutton of Glands, the Monster without Makeup, the Brute, the Creeper. You can call him anything you want, but his friends called him Rondo.

Early Life

Rondo Hatton was born on April 22, 1894.

His parents, Stewart and Emily Hatton, were itinerant college instructors – adjunct professors, basically – so the family moved around. When Rondo was born, they were teaching at Kee-Mar College in Hagerstown, Maryland. Census records put them at Hickory, North Carolina in 1900, where Rondo’s younger brother Stewart Jr. was born. Census records also put them in Charlestown, West Virginia in 1910, where Stewart Jr. died at the age of 11 from acute appendicitis.

Perhaps looking to get away from bad memories, in 1912 the family to Hillsborough County, Florida where they had some relatives. Young Rondo was a high school stand out, an all-star multi-sport athlete for the Hillsborough High Terriers, and active socially. He was also a hit with the ladies, voted “handsomest boy” in his senior class.

After graduating from high school, Rondo went on to college, though by all accounts he was more interested in sports and socializing than academics. He started at Columbia College in Missouri; then went to the North Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts, where he joined Sigma Nu fraternity; before finally ending up at Davis & Elkins College in West Virginia, where he played quarterback for the football team.

When his college days came to an end in 1916 Rondo joined the Florida National Guard. His company was called up to patrol the Texas border during the Pancho Villa Expedition. During World War I, they were sent over to France for a few months.

While in France, Rondo’s unit was supposedly gassed by the Germans and he spent months recuperating in a hospital bed. However, there are no contemporary records of an attack. That’s strange, in that the Tampa papers were breathlessly publishing every scrap they could get about their brave boys – and Rondo in particular. They published news bulletins when Rondo was out of town on vacation, when Rondo told a funny joke at the soda counter, when Rondo’s wife left the car running and it got stolen. It seems hard to believe they wouldn’t mention Rondo fighting for his life in France.

The omission doesn’t necessarily mean anything. War department records from this era are fragmentary, and Rondo’s own failure to mention it could be chalked up to a veteran’s reluctance to talk about his wartime experience. However, odds are the “gas attack” was just a story made up by a Hollywood publicist years later.

Rondo was honorably discharged and sent back to Florida in July, 1919. If he was recovering from a gas attack, he was apparently quite recovered, because he immediately joined the University of Florida Gators football team as a substitute quarterback. If it seems odd to you that a 25-year-old Army veteran who’d already graduated from college would be playing football against boys six years younger, well, it seemed odd to Florida’s opponents too, and they filed a formal protest. Rondo was forced to sit out a few games while his status was debated, but he was ultimately ruled eligible for the remainder of the season.

Now with his football playing days firmly behind him, Rondo needed something to do. He was extremely active in the American Legion, played on local intramural teams, coached the high school football team, and worked as writer and editor for the Tampa Times, the Tampa Tribune, and the Downing Sports Syndicate. He dabbled in real estate, acting as an agent for others and speculating on industrial and residential ventures. In April 1926, he married Elizabeth Immel James, a local debutante. The popular young couple was the toast of Tampa.

Those happy days were soon to end.

Acromegaly

At some point in the 1920s Rondo was diagnosed with acromegaly, a condition where the body produces excess Growth Hormone after the growth plates on the bones have fused. Rondo had developed the condition in his late teens, but now its symptoms were undeniable. His hands and feet enlarged and were prone to painful infections. His face changed as his nose, lips and brow began to swell and his jaw and chin became more prominent, until the Handsomest Boy in Hillcrest High was almost unrecognizable. His organs became enlarged, causing frequent headaches and intense pain. In later years he would develop additional complications as well, including arthritis, type 2 diabetes, and high blood pressure.

Today there are ways to stop the spread of acromegaly, but in those days there were no effective treatments. Which isn’t to say there were no treatments. With “his ten thousand friends pulling for him” Rondo underwent a series of painful facial and dental surgeries intended to slow the effects of his condition. None of them were effective, and they left him with scars on his face and metal plates in his cheeks.

To make matters worse after the 1929 stock market crash stock market Rondo’s real estate ventures went belly-up. His young wife couldn’t cope with the shame of bankruptcy and the stress of Rondo’s worsening medical condition, and divorced him in June 1930.

Early Roles

There were some signs of hope, though. In late 1929 the Lupe Vélez film Hell Harbor was being shot in Tampa, and Rondo was sent to cover it for the papers. His distinctive look caught the eye of director Henry King, who thought he could add some visual interest to a few crowd scenes and cast him as an extra. Rondo can be seen in a few scenes of the opening reel as the rough-looking proprietor of a seedy dance hall, greedily eyeing a sailor who doesn’t know he’s about to get rolled. It’s a nothing part, but Rondo makes the most of it.

King thought Rondo had talent, and tried to lure the young man back to Hollywood. At first Rondo wasn’t convinced there was money in it, but after the stock market crash he started reconsidering that position. In 1931 when William Wellman’s Safe in Hell was filming in St. Petersburg, he drove up to audition and landed a non-speaking role as a juror in the court scenes.

Movie roles were few and far between in Florida, so it was back to sportswriting for Rondo. He remained active in the community, getting married a second time to Mabel Housh in September 1934, and underwent more painful surgeries. By 1936, Rondo and his wife were ready for a change, and left to make their fortune in Hollywood.

When they arrived in California Rondo called up Henry King to see if he had any roles for him. It took a few months, but King eventually cast him in 1938’s In Old Chicago, a historically inaccurate epic about the Great Chicago Fire starring Tyrone Power, Alice Faye, and Don Ameche. Tampa papers eagerly reported on every aspect of the film’s production, creating the impression Rondo would have a major role. When the movie was released, at least one ad that ran in local papers featured Rondo’s name in bigger type than the names of the three leads put together.

Any of Rondo’s friends who went to the theater expecting to see the debut of Hollywood’s next superstar was going to be disappointed. Rondo has a decidedly minor role as the bodyguard of the film’s antagonist, Gil Warren. He has about three minutes of screen time, mostly standing in the background behind Brian Donlevy and trying to look imposing in spite of the fact the he’s clearly shorter than everyone else in the scene. He has about five lines, and his delivery is wooden and unconvincing, even on gimmes like “Thank you.” On the plus side, he’s a noticeable and visually striking presence, and his underacting is a welcome relief to the over-the-top drunken Irish accents adopted by the other bit players. And he gets to shoot Don Ameche in the back in the last reel, so he’s got that going for him.

Rondo’s appearance made him stand out, but it also made it difficult for him to find regular acting roles. He appeared as a bit player in fourteen films over the next seven years – frequently in grotesque roles like “convict” or “leper” or “hunchback” or “ugly man.”

Some highlights from this era include a quick appearance in 1938’s Alexander’s Ragtime Band, a part in 1939’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame (where he loses an “ugly man” contest to Charles Laughton’s Quasimodo), and the role of Gabe Hart in the 1943 adaptation of The Ox-Bow Incident. My favorite, though, has to be the 1944 comedy Johnny Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, where he appears as a grotesque undertaker in a short scene that plays to all his strengths.

Pearl of Death (1944) as “The Hoxton Creeper”

Rondo’s luck changed when Universal cast him in 1944’s Pearl of Death, a Basil Rathbone Sherlock Holmes film loosely based on the short story “The Adventure of the Six Napoleons.” Rondo plays “The Hoxton Creeper,” a silent killer who snaps spines for the movie’s antagonist only to betray him at Holmes’ urging. He doesn’t have any spoken dialogue and for most of the movie is only seen in silhouette or dark shadow, but he makes for a frightening figure in a padded suit that bulks out his otherwise lanky frame and the close-up shots of his giant hands and oddly-proportioned face are genuinely terrifying. For his five minutes of screen time, Hatton was paid $400 – about $5,000 in modern money.

The Creeper character struck a chord with audiences – and with Universal executives, too. They put him under contract and announced they were developing a new slate of horror characters, which would include Rondo as the Creeper. Those films would take some time to develop, though, and Universal wanted to strike while the iron was hot. So they created roles for Rondo in films they already had in development.

Jungle Captive (1945) as “Moloch the Brute”

First he was hastily written into 1945’s Jungle Captive, the last film to feature Z-list Universal monster “Paula, the Ape Woman.” Rondo plays “Moloch the Brute,” the assistant of an evil endocrinologist who seeks to use the blood of his lab assistant to restore the Ape Woman to life. He isn’t given much to do other than look imposing and deliver some exposition, and he does neither well. Previous films had used unusual angles and clever staging to make Rondo look taller and more imposing, but director Harold Young wasn’t smart enough to do any of that. This was also the first time Rondo had extensive dialogue in a movie, and while he’s still not a good actor, his line readings are okay – not great, just okay.

That voice, though! It’s scratchy and wheezy, and it sounds like he’s doing a bad impression of Eddie “Rochester” Anderson. It undercuts the menace he otherwise effortlessly conveys. Rondo’s acromegaly was clearly making it increasingly hard for him to breathe, and it’s unusual that the producer and director chose to leave his performance in the final cut instead of overdubbing his dialogue or reassigning it to other characters.

Rondo is also treated very strangely in the movie. Other characters are constantly calling him hideous and brutish and in a way that seems structured to be deliberately cruel. Maybe Universal was just trying to talk up their new horror star, or maybe the scriptwriter was upset at having to shoehorn a new character into the turd he’d just finished polishing. We’ll never know how Rondo felt about it, though, because he kept mum. Maybe he was just happy to have work.

The Spider-Woman Strikes Back (1945) as “Mario the Monster Man”

Rondo’s next outing was 1945’s The Spider Woman Strikes Back, where he plays “Mario, the Monster Man,” the hideous henchman of the evil Zenobia Dollard, who uses tropical orchids to murder ranchers in an an isolated western town. The film is ostensibly another Sherlock Holmes spin-off – lead actress Gale Sondergard had previously menaced Basil Rathbone as a similar (but unrelated) character in 1944’s The Spider Woman.

This time out, Rondo doesn’t have any dialogue. He can play to his strengths like lurking in the background, looking ugly, and occasionally bringing a tray of poisoned milk to the film’s lead ingenue. Director Arthur Lubin can’t save the terrible script, but he does manage to inject some visual interest into the proceedings, which makes it one of Rondo’s more successful outings from that era. If the movies were getting worse, at least the paychecks were getting bigger. Rondo was now commanding $1,250 per picture, or about $18,000 in modern money.

House of Horrors (1945) as “The Creeper”

In September 1945, Universal was finally ready to begin production on House of Horrors, the first real movie to star the Creeper. Rondo stars as a fugitive killer with a compulsion to murder women. While escaping from the police he’s rescued by a failed abstract sculptor and becomes not only his muse, but his instrument of revenge on the rest of the art world.

The movie plays to Rondo’s strengths – he has dialogue, but it’s short and structured to make his affectless line readings seem chilling rather than comical. (My favorite line? When asked why he had to kill a woman, his only response is, “She screamed.”) Director Jean Yarborough and cinematographer Maury Gertsman film the introduction and horror sequences with some real flair that showcase Rondo’s appearance, though even they can’t save the movie from scene after interminable scene of nattering art critics and insufferably smug police detectives.

The only real problem is that even though the picture had been developed to be a Rondo Hatton vehicle, the script reduces the Creeper to something less than a character and more of a prop. Instead, the spotlight is stolen by Martin Kosleck and his scenery-chewing performance as crazed sculptor Marcel de Lange. Maybe it was something that happened during filming, or maybe this was a sign that Universal was no longer so high on Rondo. In either case, he was already under contract, so they were going to make another Creeper movie anyway.

The Brute Man (1946) as “The Creeper”

In The Brute Man the Creeper is revealed to have survived his seeming death at the end of the previous film. He returns to his hometown where he goes on a killing spree. It’s eventually discovered that the Creeper is a formerly handsome college athlete disfigured by a freak chemical accident, who is taking revenge on those responsible. He also falls in love with a blind woman who can’t see how hideous he is – though he still tries to murder her in the end.

You may notice that, aside from all the murdering, that sounds like a luridly sensational version of Rondo’s Hollywood bio – a popular football star, disfigured by a gas attack. That’s not a coincidence. Universal had decided if they were going to exploit Hatton’s deformities, they might as well go all in.

Given that House of Horrors made effective use of Rondo, you’d think a sequel put together by the same writer, director, and cinematographer would have been adequate at least. You’d be wrong. The production team seemed determined to not learn any lessons from their previous outing. Once again, the film focuses on characters other than Rondo, and this time the actors don’t even bother to justify it with hammy performances. Rondo gets way too much dialogue and he’s even wheezier and more unconvincing than usual. Everything about the film drags – it’s less than an hour long, and somehow feels like it’s three times longer.

On the plus side, the opening sequence is great. Worth a watch all by itself. But turn the movie off immediately afterwards.

For his work on The Brute Man, Rondo earned $3,500, or about $50,000 in modern money. The films may not have been any good, but he was finally earning enough money to pay for his medical treatments and take care of his family.

Death and Legacy

Rondo never lived to see his star turns on the big screen. After production on The Brute Man finished in December 1945 his health took a turn for the worse. He was bedridden for a few months, and on February 2, 1946 he died of a massive heart attack at age 51. His remains were shipped back to Tampa, where is buried in the American Legion cemetery.

In the months after Hatton’s death, Universal merged with International Pictures. The new Universal-International was all about prestige – they decided they would no longer produce B pictures and washed their hands of the ones they still had in the pipeline. They sold the unreleased The Brute Man to PRC for $125,000 – an amount that barely covered the negative cost.

Though Rondo’s career was short and largely unsuccessful, his striking presence remained a pop culture presence that influences us to this day. Most notably, his physical appearance inspired the character of “Lothar” in Dave Steven’s Rocketeer comics and the Disney movie based on them. In a less sensitive vein, Rondo was also “honored” by writer Joyce Brabner when she founded “The Rondo Hatton Center for the Deforming Arts” in Wilmington, Delaware. In 1996 The Brute Man was featured in the seventh season of Mystery Science Theater 3000, paired with the short film “The Chicken of Tomorrow.”

Since 2002, the fan-voted Rondo Hatton Classic Horror Awards have honored winners with a duplicate of Marcel de Lange’s bust of The Creeper from House of Horrors. Which means that one of Hollywood’s unjustly forgotten stars is literally the Face of Horror.

Connections

Rondo Hatton moved to Hillsborough County, Florida in 1912. You know who was also new to Tampa in 1912, was voted the handsomest boy in his high school, invested heavily in Florida real estate, and lost his shirt after Black Monday? Our friend Bebe Rebozo (“Be My Bebe”). I’m not saying a teenage Rondo ever babysat the infant Bebe, but I’m not saying it didn’t happen either. Alternate history buffs, hop to it!

Rondo’s Pearl of Death co-star Miles Mander was a good friend of famous aviator Claude Grahame-White (“The Realest Housewife of Beverly Hills”).

Charles Laughton, whose Quasimodo handily defeated Rondo in an “ugly man” contest, would stay in the Garden of Allah (“The Garden of Oblivion”) hotel whenever he was in Hollywood.

Rondo was featured in 1945’s Jungle Captive, the third Universal picture to feature Paula, the Ape Woman. Vicky Lane starred in the title role, but she was a replacement for the series original star: Burnu Acquanetta (“Burning Fire, Deep Water”).

Rondo isn’t our only connection to Pancho Villa. On the other side of the border, “archaeologist” and scam artist Frederick Albert Mitchell-Hedges (“Lost Legacy”). claimed to spend a year fighting with Villa.

References

- Mallory, Michael. Universal Studios Monsters: A Legacy of Horror. New York: Universe Publishing, 2009.

- Weaver, Tom, et al. Universal Horrors: The Studio’s Classic Films, 1931-1946. (Second Edition). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2007.

- “Acromegaly.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acromegaly. Accessed 3/25/2019.

- “Wikipedia: Rondo Hatton” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rondo_Hatton. Accessed 3/25/2019.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: