Neither Here Nor There

the strange second life of a proud people

In 1889, Will Allen Dromgoole, a reporter for Nashville’s Daily American, was running around the state house trying to get quotes for a story when she heard a word that stopped her dead in her tracks.

That word was “Melungeon.”

Now, she knew what a Melungeon was. It was a fairy tale that everyone in Tennessee knew. You see, back in the day Old Horney (that’s the Devil, son) was wandering the land when he decided to settle in Tennessee because it reminded him of his beloved tarnation. He got hisself hitched to a pretty little Injun gal who spat out whole litter of demons, the Melungeons. They mostly kept to themselves up in their mountain caves, but when they got hungry they would turn invisible and go out to find naughty little boys and girls to eat.

What shocked Dromgoole was that the two men were talking about Melungeons as if they were real. She interjected herself into the conversation and discovered two fascinating things. First, Melungeons were real. And second, while they weren’t invisible flying ogres, no one could agree on exactly what they were.

“Hillbillies.”

“Godless degenerates.”

“Lazy Indian sneakers.”

“They’re Portuguese n*****s.”

“A Melungeon isn’t a n*****, and he isn’t an Indian, and he isn’t a white man. God only knows what he is. I should call him a Democrat, only he always votes the Republican ticket.”

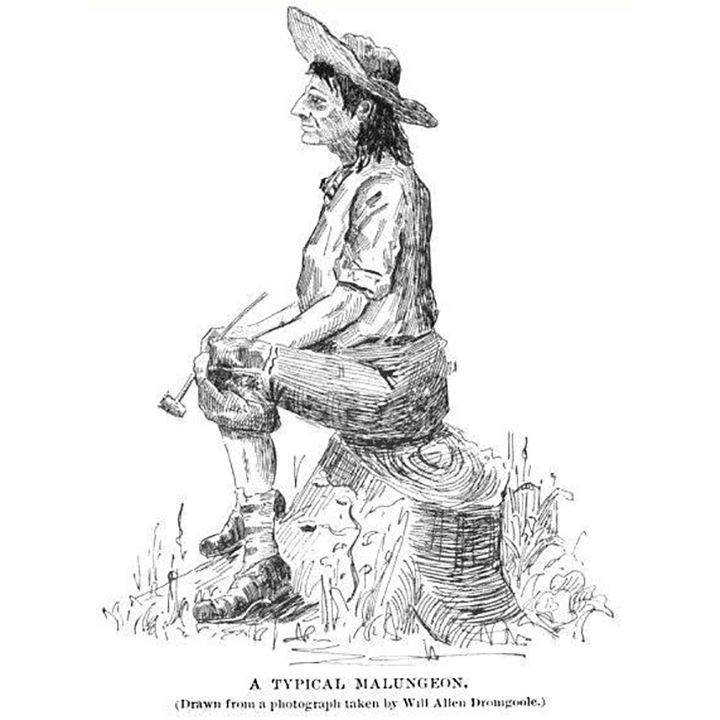

They couldn’t even agree on how to spell it. The most widely accepted spelling was M-E-L-U-N-G-E-O-N, but there was also “Malungeon” with an A, “Melungin” with an I, “Melunjin” with a J, “Malugin” with a whole missing syllable, and even “Malungu” and “Malongo.”

They did have tales of the Melungeons which were new to Dromgoole.

They were an ancient race of unknown origin. The first European settlers who moved over the Appalachians were surprised to find the Melungeons already living on the land, and for some reason, speaking an archaic dialect of Elizabethan English. They were even more surprised by the Melungeons’ appearance. They weren’t white, they weren’t Native Americans, but something entirely different. The settlers eventually chased the Melungeons out of the fertile valleys and up into the rocky hills. In their isolation they turned into godless heathens, drunken idlers who refused to work the land and supported themselves in unlawful ways: making moonshine, robbing their neighbors, and counterfeiting. Indeed, they were supposed to be such good forgers that their fake gold coins had nearly bankrupted the Confederacy.

One legislator mentioned that there was a Melungeon community in his district, up on Newman’s Ridge near Sneedsville. That was all Will Allen Dromgoole needed to hear. She packed her bags and went off find herself some real-life boogeymen.

Dromgoole had been hoping her trip into the mountains would be like a visit to Brigadoon, full of magic and whimsy and adventure with some life-affirming lessons tacked on to the end. All she found was disappointment. As far as she could tell the Melungeons were not magical creatures, just garden variety hill folk, degenerates too lazy and shiftless to work and too drunk to care that they lived in squalor. All they had time for was fighting and fu….n adult times with their special friends. (Ask your mommy and/or daddy.)

She would have called them poor white trash, except they weren’t white. Mind you, they weren’t black either. Oh, they had dark skin, but that was where it ended. Some had straight hair and Caucasian facial features. Others looked more like Native Americans, and still others like Orientals. She first thought they might be biracial, but that wasn’t possible because they bred like rabbits and everyone knew that mixed race children were sterile like mules. (A common misconception at the time.) All the Melungeons would say about it was that they were Portuguese, as if that explained anything.

Will Allen Dromgoole was an intrepid girl reporter through and through. If there was a story to be found, then by gum, she would find it. She put up her hair, interviewed everyone who would talk to her, read every legal record and church register she could get her hands on. It took her a few weeks but she finally thought she had unraveled the mystery of the Melungeons.

They were not some ancient race. The original Melungeons seemed to be descended from Scotch-Irish settlers like Jim Mullins who moved into the area in the early 1700s, took Native American wives, and raised their children to be fine, upstanding citizens. She called this group the “Ridgemanites.”

In the 1790s the Ridgemanites got new neighbors, the mulatto Collins and Gibson families. Their patriarchs, Vardy Collins and Buck Gibson, ran a scam where Vardy would darken Buck’s skin with dye, sell him as a slave, and split town. Buck would lighten up after a few days, be freed or escape, and meet back up with Vardy so they could run the scam again. Eventually they made their way so far west that they ran out of farmers to scam, and settled on Newman’s Ridge next to the Ridgemanites.

A few years later they were joined by two black families: first the Goins and later the Denhans, who claimed descent from slaves marooned in the Carolinas by Portuguese pirates.

Over time the Ridgemantes intermixed with their black and mulatto neighbors. The dilution of their white blood meant the loss of all the nobility and intelligence they had inherited from their European and Native American forebears. Within a few generations the transformation was complete. The Ridgemanites were no longer noble citizen-farmers of European stock but shifty, lazy, mixed-race abominations. Melungeons.

Not surprisingly the residents of Newman’s Ridge were not happy about Dromgoole’s conclusions and drove her out of town. She had the last laugh, though. She wound up publishing stories of her trip in newspapers across the nation, where they received great acclaim.

The Actual Melungeons

It should not surprise you to learn that most of what Will Allen Dromgoole wrote about the Melungeons was wrong.

I am tempted to go easy on her. After all, it’s entirely possible that a hundred years from now someone will be making a holovid about how everything in this podcast is wrong. Then again, I am relying on a hundred years of work by dedicated historians, ethnologists, and sociologists while Dromgoole was relying on some half-heard rumors that she filtered through the racism, classism, and priggish morality that predominated in black and white big mustache racist times. So screw her.

She was right that there were originally two separate but related groups that were lumped together under the name “Melungeon.” However, the first group were not Scotch-Irish settlers who married Native Americans, but African-Americans.

African slaves first arrived in America in 1619, when a British pirate ship docked at Jamestown and sold several Angolan slaves captured from Portuguese merchant vessels. Several of these slaves feature prominently in Melungeon family trees, including John Gowen and Margaret Cornish. (Those are their slave names and not their real names, of course.) Some of these slaves earned their freedom and settled in the tidewater regions of Virginia and the Carolinas. They had children with each other, and also with white colonists and Native Americans.

As the institution of slavery became more ingrained into the fabric of society, so did racism. By the end of the Seventeenth Century only white men could vote, own property, serve on juries, or even testify in court. Blacks and enjoyed none of those privileges and protections, and Native Americans only had the limited rights granted to them by treaty. Mixed-race individuals were considered abominations that violated strict racial hierarchies.

In the late Eighteenth Century one of these mixed-race groups began migrating over the Appalachians into an area that’s now split between Virginia, West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Their hope was that on the frontier they could finally get out from under whitey’s thumb. It was a fool’s hope. White settlers kept pushing the frontier west and it wasn’t long before they were right back in the thick of it.

It’s not entirely clear how this group came to be called “Melungeons.” The name first appears in the minutes of the Stony Creek Primitive Baptist Church from 1813, where the writer complains about “them Melungins” who have moved into the area.

It has been suggested that the name is derived from the Angolan malungu, or the Afro-Portuguese melungo, or the Kongolese mu alongo or maybe melugo or melango, meaning “person in the same boat”; from a different Afro-Portuguese word meaning “white person;” from the Greek melon or the Italian melongena, meaning dark-skinned; from the French melange, meaning mixed; from the Spanish malungo, meaning “chubby”; from the English malingerer, meaning “lazy”, or malengin, meaning “ill-intent”; or even from some mangled combination of Mullins and Goins, two prominent Melungeon surnames.

What Melungeon really means, though, is “I don’t know what you are, but I know it’s not good.”

Mixed-race individuals existed in limbo, neither black nor white nor Native American. That confounded racists who wanted nice clean racial categories. Their solution was to create an overflow category, a group that had none of the special protections Native Americans received, and which couldn’t be treated as harshly as blacks, but who definitely weren’t getting all the privileges of being white either.

This is where the second group of historical Melungeons comes into the picture: everyone who wasn’t part of the original Melungeons, but who also didn’t fit nicely into an existing category. If you weren’t white or black or an Injun or a Chinaman, well, well, you must be a Melungeon. Go and git up on that ridge with the others.

For the most part Melungeons were not appreciably different from any other group of hill folk or mountain men. The stereotype was that they were poor, ignorant, lawless, immoral — even though they weren’t actually all that different from the folks down in the valleys.

In the 1830s and 1840s, new laws and regulations began making life difficult for mixed-race individuals. The most infamous example would be the “one drop” rule which said if you had a single drop of black blood in you, you were black. Native Americans also had many of their legal protections stripped away, and it was made much harder to claim Native American ancestry.

Mixed-race groups responded to these new laws in the only way they could. They couldn’t pass for French or German or English, but they could claim to be something else, some heritage that had just enough whiteness that they could hold onto their civil rights. It helped if it was something exotic which none of their neighbors had ever seen. They could be an Aztecs a Romani or Moors. They could be the remnants of some long-lost civilization, like Phoenician mound-builders or the Lost Tribes of Israel or the Welsh colony of Prince Madoc or the Lost Colony of Roanoke. They could be descended from explorers like Spanish conquistadores or Zeng He’s treasure fleet or the Knights Templar.

For Melungeons, the heritage of choice was Portuguese. Why not? Their ancestors had been enslaved by the Portuguese, didn’t that make them Portuguese too in a roundabout way?

Amazingly, the law took their side. In 1845 the state of Tennessee arrested eight Melungeons for illegally voting in the previous year’s elections. The prosecution argued that the defendants were mixed-race, which made them black, and therefore they couldn’t vote. The defense argued that they couldn’t be mixed-race because they were fertile, and everyone knew mixed-race people were sterile, and therefore they must be Portuguese and could vote. The judge agreed with the defendants.

The decision was bolstered by an 1855 libel suit, where a judge ruled for the plaintiff even though the defendant spluttered that the plaintiff had to be black because he had that “negro smell.”

There was the occasional setback — in an 1889 trial one Melungeon was ruled to be black because his feet were “too flat” to be white — but in general, when Melungeons went to court, they won.

Once Melungeons had binding legal decisions declaring them to be Portuguese, they used them as a wedge to force open more doors — voting rights, property rights, even allowing their children to attend white schools instead of black schools.

The white population responded by having a full blown racial panic attack. They all knew the Melungeons weren’t really white, and if the law wasn’t going to protect them they would have to protect themselves through social pressure. Melungeons were ostracized and discriminated against more than ever.

During the heyday of the eugenics movement things got really dark. State authorities like Virginia’s Walter Plecker used extensive genealogical records and (now discredited) racist physiological techniques to get many Melungeons reclassified back from white to mixed-race, making them targets of eugenics programs like forced sterilization and long-term confinement in homes for the feeble-minded and infirm.

Relief finally arrived in the 1930s, when the New Deal brought better jobs and improved transportation infrastructure to rural areas. Melungeons took advantage of these opportunities by moving out, to distant communities where no one knew or cared who they were. Often they destroyed family records and refused to talk about their uncomfortable pasts. Even their own children were kept in the dark, because what they knew couldn’t hurt them.

Hiding in plain sight turned out to be a much better strategy for avoiding discrimination than legal subterfuge. When sociologists and ethnologists attempted to seriously study Melungeons and similar ethnic groups in the 1950s they were shocked to find that many of them had just disappeared. They had vanished into the crowd, melted away in the melting pot, never to be seen again.

They had finally become what legend had wanted them to be all along: a lost race.

The Modern Melungeon Movement

In the modern world, though, nothing stays lost for long.

In 1988 Dr. N. Brent Kennedy, a 33-year-old academic in Tennessee, fell seriously ill. He was in and out of hospitals for months before he was correctly diagnosed with sarcoidosis, a rare autoimmune condition. When he read up on sarcoidosis, he realized he was a rare statistical outlier — in the United States, 80% of people with sarcoidosis are black, 10% are of Middle Eastern or Portuguese descent, and 10% are Appalachian whites.

Growing up in Wise, VA Kennedy had always been told that his family was Scotch-Irish. That seemed odd, because his mother and many members of her family had had a notably dark complexion. He began to ask himself why so many members of his family had a “Mediterranean appearance” and wondering if that might explain his sarcoidosis.

Kennedy started researching his family tree and was surprised when his relatives refused to help him out. More than that. One of them set a box full of family mementos on fire in front of him, and another told him, “I hope you burn in hell.” In the end, he decided his family had to be Melungeons. That would explain the secrecy and hostility, and their “Portuguese ancestry” would explain why he had come down with sarcoidosis.

The more Kennedy thought about it, the more he didn’t like the idea that Melungeons were Portuguese. They were “too dark” to be Portuguese and didn’t seem to have retained any Portuguese customs or language. (Of course, things like this also vanish quickly as populations assimilate — I’m technically third-generation Irish-American and it’s not like I go out step dancing every week.) He also hated the explanation that ethnologists had come up for the so-called “little races,” that they were “tri-racial isolates,” for being too reductive.

In the end Kennedy decided there was only one thing the Melungeons could be: the descendants Turkish galley slaves who were stranded in the Carolinas by Sir Frances Drake in 1567, who mixed with local Native American tribes to form a new race of people.

After that revelation everything else just sort of clicked into place. It explained the sarcoidosis, of course. Turks were darker than the Portuguese. The word “Melungeon” must be derived from the Turkish melun jinn, meaning “damned ones,” referring to their stranding in the New World. He also began seeing Turkish loan words scattered across the American landscape: Allah Bamya, “God’s cemetery”; Tenasüh, “a place where souls move about”; and Dilhah Yer, “the beautiful land.”

At this point your horse hockey detector should be going off. N. Brent Kennedy was an academic, but not a historian, ethnologist or linguist. While he seems to have been a kind and thoughtful person who I would have loved to have a cup coffee with, that doesn’t mean he didn’t have his flaws, most notably unconscious racism and tunnel blindness, which led him to ignore inconvenient facts. His own facts are often taken out of context and misinterpreted, and he rarely sites sources in his writing.

Let’s start with his assumption that his family had “Mediterranean” origins. I find myself wondering, “What is a Mediterranean person? Is that a real thing? What are they supposed to look like?” I also find myself wondering why, if 80% of sarcoidosis sufferers are African-American, Kennedy never entertained the thought that his ancestors were black.

Are Melungeons descended from Turkish galley slaves? It is true that Drake seems to have taken some 600 or so Turkish sailors as hostages, only 100 of whom were ransomed back to the Sultan of Turkey. There is no record of what happened to the others at all. They may have been sold as slaves or they may have just died. There is no evidence whatsoever for Kennedy’s hypothesis that Drake stranded them in the Carolinas.

Kennedy’s Turkish Melungeons were supposedly encountered by European explorers in the Carolinas in the 1600s, which he bases on scattered reports of unusual tribes speaking an antiquated dialect of English. One wonders, though, why Turkish Melungeons would be speaking English at all and not, you know, Turkish. In any case, these stories are rarely contemporary and never corroborated. But Kennedy needs them to be true for his hypothesis, because he also needs these Turkish Melungeons to migrate west to Tennessee prior to the 1750s to match similarly unsubstantiated tales from a few decades later.

As for his linguistic theories, the less said the better. Alabama and Tennessee are definitely loan words from Creek and Cherokee, though Kennedy would argue that the Creek and Cherokee lifted them from the Turks. Delaware, though, is not debatable, because it is not a loan word from a Native American language. It is derived from the title of Virginia’s first governor, Thomas West, the Third Baron De La Warr. And also, no one would ever describe Delaware as “the beautiful land.”

Kennedy seemed undaunted by the fact that his theories received virtually no support from the academic community. Instead he founded the Melungeon Heritage Associate (MHA) and set up a website with a short checklist people could use to self-identify as Melungeons. Items on the checklist included:

- Extremely generic physical characteristics — dark skin, thin lips, narrow face, high cheekbones, wide forehead, wavy black hair.

- Extremely specific physical characteristics — polydactylism, the “Anatolian ridge” (a golf-ball sized lump below the Adam’s apple), the so-called “Asian eye fold”, and “shovel teeth” — which sound more like the signs of inbreeding and malnutrition than a marker of any specific ethnic heritage.

- A family history of certain diseases and conditions which are most prevalent in several unrelated non-European heritages — Bechet’s syndrome (Asian communities), Machado-Joseph’s disease and familial Mediterranean fever (Jewish communities), sarcoidosis (African-American communities) and thalassemia (everywhere but Northern Europe).

- Ancestors who resided in specific counties in the “historic core area,” especially if they were classified as colored in census data.

- A long list of specific surnames — most of them Scotch-Irish and therefore extremely common.

You can probably figure out what happened next: tens of thousands of people began to identify as Melungeons, based on a vague checklist they found on a website somewhere.

Are these modern Melungeons actually the descendants of older Melungeons? Some of them almost certainly are, and have the genealogies that can prove it. Many, though, are basing their self-diagnosis on things like “weird vibes” and not knowing much about their family history.

Why would someone voluntarily choose to identify as a mixed-raced minority group, when prejudice and bigotry are still rampant in this country? Well, that prejudice and bigotry hits harder on certain ethnic groups than others, and bigots may not have the same sort of strong feelings about Turks that they do about African-Americans and Native Americans.

These modern Melungeons may also be seeking a sense of belonging. For a long time the goal of many groups was assimilation, the point where they stopped being German or French or Irish and just became American, but in the Twentieth Century that started to flip and people became justifiably proud of their ethnic and cultural heritage. Those who had already assimilated to a point where they had lost their ethnic identity are often left out of this “ethnic reverie” because Americanness and whiteness are hollow constructs whose cultures and rituals are shallow and meaningless. By identifying as Melungeons these people are trying to find a culture and identity of their own. It’s like when someone you know tries to make themselves seem exotic by claiming they have a Cherokee princess somewhere in the family tree — which is also something that a lot of modern Melungeons do.

Of course, there’s always the question of exactly what culture they are trying to identify with. The original group of Melungeons, the ones descended from Angolan slaves, have a culture and heritage that might be worth reconnecting with. The second-wave Melungeons don’t have a common culture or heritage, other than living on the wrong side of the tracks, but this is the group that most modern Melungeons identify with. It turns out that many of them are open to the idea of being not-white but not nearly as open to the idea of being black.

For the moment, let’s assume only the best intentions for everyone involved in the modern Melungeon movement and step back from it for a second. It is fascinating to watch a group construct a new identity for themselves in real time. Okay, sure, it happens all the time on the Internet, but those are typically shallow faddish identities that are quickly discarded, and this is something meaningful, an attempt to construct an ethnicity. What complicates this creation is how the present interacts with the past. Are these modern Melungeons the same as the original Melungeons? Could they be, with time? Should they be? Were the original Melungeons ever really a thing in the first place?

Let’s be blunt, I am not the right person to weigh in on serious discussions about identity and belonging. So let’s change the topic to something I can weigh in on: are the Melungeons really Portuguese or Turkish? Fortunately, we live in the Twenty-First Century, where these questions can be solved through DNA testing.

Melungeons have been the subjects of small-scale DNA studies in 1979, 1990, 2002, 2010, and 2012. And the results have been… inconclusive at best.

Most self-identified Melungeons have mostly northern European genetic markers, with a smattering of markers from other regions, including Iberia and Anatolia. Kennedy and the Melungeon Heritage Association have touted those results as proof of their claims, while scientists more cautiously note that those results make Melungeons genetically indistinguishable from most of their white neighbors.

Other Melungeons are still predominantly northern European but have significant African and Native American ancestry. That seems to suggest that the historical Melungeons were what people thought they were thought to be all along: free people of color with white partners.

What does that tell us? Well, mostly nothing. One of the scientists quoted in Melissa Shrift’s Becoming Melungeon put it best:

The DNA told people who felt a deep connection to American Indians that their ancestors were mostly white. It informed a lot of blonde-haired, blue-eyed people that at least some of their forebears were black.

Melissa Schrift, Becoming Melungeon

So maybe the next time when your aunt tells you that your ancestors were Cherokee princesses and Turkish galley slaves, take that with a grain of salt.

Connections

Attempting to pass as another race or ethnic group is hardly a survival strategy unique to the Melungeons. We’ve countered plenty of examples before, from Dr. Dinshah Ghadiali (“Normalating”) to Burnu Aquanetta (“Burning Fire, Deep Water”) to the United Nuwaubian Nation of Moors (“Space is the Place”).

For other improbably stories of Portuguese adventures in the United States, check out the first episode of our “Westward Huss” series for the story of Dighton Rock and very tenuous connection to Portuguese explorer Miguel Corte-Real.

For more about the shameful history of eugenics, check out our episode about the supposedly degenerate Kallikak family. (“Common Clay”).

Sources

- Allen, S.D. “More on the Free Black Population of the Southern Appalachina Mountains: Speculation on the North African Connection.” Journal of Black Studies, Volume 25, Number 6 (July 1995).

- Berry, Brewton. Almost White. London: Collier Books, 1969.

- Bible, Jean Patterson. Melungeons Yesterday and Today. Rogersville, TN: East Tennessee Printing Company, 1975.

- Dromgoole, Will Allen. The Malungeons. Boston: Arena Publishing, 1891.

- Dromgoole, Will Allen. The Malungeon Tree and Its Four Branches. Boston: Arena Publishing, 1891.

- Elliott, Carl. “Adventures in the Gene Pool.” The Wilson Quarterly, Volume 27, Number 1 (Winter 2003).

- Everett, C.S. “Melungeon History and Myth.” Appalachian Journal, Volume 26, Number 4 (Summer 1999).

- Groover, Mark D. “Creolization and the Archaeology of Multiethnic Households in the American South.” Historical Archaeology, Volume 34, Number 2 (2000).

- Gross, Ariela. “Of Portuguese Origin: Litigating Identity and Citizenship among the Little Races in Nineteenth-Century America.” Law and History Review, Volume 25, Number 3 (Fall 2007).

- Hirshman, Elizabeth Caldwell. Melungeons: The Last Lost Tribe in America. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005.

- Kennedy, N. Brent. The Melungeons: The Resurrection of a Proud People. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 1994.

- Hashaw, Tim. Children of Perdition: Melungeons and the Struggle of Mixed America. Mercer, GA: Mercer University Press, 2006.

- Henige, David. “Origin Traditions of American Racial Isolates: A Case of Something Borrowed.” Appalachian Journal, Volume 11, Number 3 (Spring 1984).

- Henige, David and Wilson, Darlene. “Brent Kennedy’s ‘Melungeons.'” Appalachian Journal, Volume 25, Number 3 (Spring 1998).

- Hirshman, Elizabeth Caldwell. Melungeons: The Last Lost Tribe in America. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2005.

- Ivey, Saundra Keyes. “Ascribed Ethnicity and the Ethnic Display Event: The Melungeons of Hancock County, Tennessee.” Western Folklore, Volume 36, Number 1 (January 1977).

- Price, Edward T. “The Melungeons: A Mixed-Blood Strain of the Southern Appalachians.” Geographical Review, Volume 41, Number 2 (April 1951).

- Puckett, Anita. “The Melungeon Identity Movement and the Construction of Appalachian Whiteness.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, Volume 11, Number 1 (June 2001).

- Reed, John Shelton. “Mixing in the Mountains.” Southern Cultures, Volume 3, Number 4 (Winter 1997).

- Schrift, Melissa. Becoming Melungeon: Making an Ethnic Identity in the Appalachian South. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2013.

- Vande Brake, Katherine. Through the Back Door: Melungeon Literacies and Twenty-First Century Technologies. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2009.

- Yates, Donald N. and Hirschman, Elizabeth C. “Toward a Genetic Profile of Melungeons in SOuthern Appalachia.” Appalachian Journal, Volume 38, Number 1 (Fall 2010).

- “Negro speaking!” Hiwasse (TN) Patriot, 27 Oct 1840.

- “The Melungens.” Littell’s Living Age, Volume 20 (March 1849).

- “The Melungeons.” Washington Evening Star, 8 Feb 1889.

- “Melungeon theory knocked out.” Morristown (TN) Republican, 21 Aug 1897.

- “An elephantine old girl.” Raleigh (NC) Farmer and Mechanic, 20 Sep 1898.

- Amer, R.O. “Strange folks of the Ozarks.” Nashville Tennessean, 26 Jun 1910

- King, Lucy S.V. “Origin of ‘Melungeon.'” Nashville Tennessean, 26 Jun 1910.

- Shepherd, Judge Lewis. “Who and what are the Melungeons?” Nashville Tennessean, 26 Jun 1910.

- Worden, William. “Sons of the Legend.” Saturday Evening Post, October 18, 1947.

- Fort, John P. “The origin of Melungeons is shrouded in Mystery.” Chattanooga News, 20 Oct 1923.

- Rogers, T.A. “A romance of the Melungeons.” Chattanooga Sunday Times Magazine, 21 Jun 1936.

- Morello, Carol. “Finding light from an obscure past.” Boston Globe, 1 Jun 2000.

- Marshall, Andrew. “Not black or white, but a breed apart.” London Observer, 4 Jun 2000.

- Hardcastle, Martha. “Landmark DNA study to trace ancestry.” Dayton Daily News, 14 Jun 2001.

- “DNA study of Melungeons rady.” Danville (KY) Advocate-Messenger, 16 Jun 2001.

- Kahn, Chris. “DNA offers new look at mixed heritage of Melungeon people.” Miami Herald, 20 Jun 2002.

- Loller, Travis. “Origins of Melungeons examined.” Asheveille (NC) Citizen-Times, 27 May 2012.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: