Rapscallions!

"Resist at Your Peril!"

Okay, so what do you need to know from the previous episode?

In the final years of the American Civil War, it became obvious to the Confederacy that it could not win by conventional means. It became desperate to find something that would change that outcome, and increasingly turned to cloak-and-dagger strategies: sabotage, subterfuge, and terror.

Eventually the Confederates established a spy ring in Canada run by three men: money man Jacob Thompson, James Buchanan’s former Secretary of the Interior; charming Clement Claiborne Clay, former Senator from Alabama; and reliable James P. Holcombe, the man who could actually get things done. For an entire year they were behind any number of audacious, insane, and utterly outrageous plots against the Union.

The first of these plots was the Great Northwestern Conspiracy, a bonkers plan to free Confederate soldiers from prisoner-of-war camps, who would then help Copperheads overthrow state governments and secede to form a “Northwest Confederacy.” It failed spectacularly, mostly because no one involved had the balls to actually go through with it.

This is the story of one of their other plots.

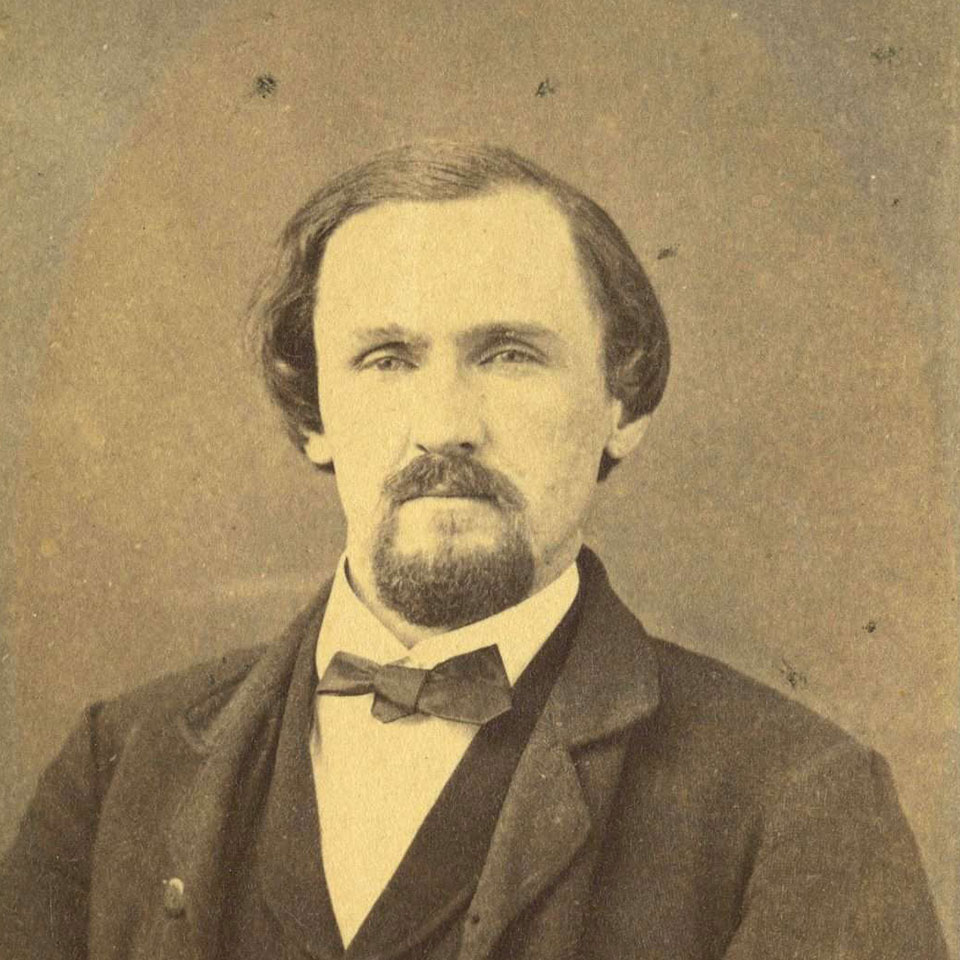

John Yates Beall

John Yates Beall — it’s spelled B-E-A-L-L but pronounced Bell — John Yates Beall was born on January 1, 1835 to a socially prominent family from Charles Town, Virginia (now West Virginia). He was a precocious young lad with a promising future.

When the Civil War broke out, Beall dropped out of the University of Virginia’s law school and joined the Second Virginia Infantry. Alas, his military career was cut short on October 16, 1861. At the Battle of Bolivar Heights he took a bullet through the lungs. To make matters worse, during his recovery he became consumptive. (Which is to say that he contracted tuberculosis; no one tell John Green.)

Beall was declared unfit for active military duty. Dejected, he drifted north and for a while worked at a mill in Cascade, Iowa. When he thought he had recovered he decided to travel to England to volunteer for the Confederate Navy, only to be told that a long sea voyage was inadvisable because his wound had not fully healed.

Johnson’s Island

That wasn’t enough for Beall, though, and in early 1863 he went back to Richmond to pitch them a cunning plan that could not fail.

One of the most pressing issues of the Civil War was what to do with prisoners-of-war. Neither side had anticipated a protracted war, or the sheer quantities of prisoners they have to deal with. Weeks into the conflict existing prisons and jails were overstuffed to the point of bursting. To relieve this pressure existing facilities were hastily converted into prisoner-of-war camps but even those were not sufficient to meet demand.

One of the Union’s most famous prisoner-of-war camps was built on Johnson’s Island, in Lake Erie just outside of Sandusky, Ohio. (For you coaster-heads out there, if you’re lucky you can see it from Cedar Point on a clear day.)

It was a great location for a prison, about three miles offshore with no direct connection to the mainland. There was no way that anyone could approach the island from any direction without being spotted. It was also relatively flat, meaning that one could monitor the entire area with a few well-placed guard towers. The isolation and topography made it possible to control a large number of prisoners with a small number of guards, barely more than a single battalion.

Johnson’s Island was originally intended to be a depot for all captured Confederate soldiers, but like every other prison camp it wound up being overwhelmed by the sheer number of prisoners being taken. At its most crowded it held 3,000 prisoners in an area originally meant to hold about 2,000 — a recipe for disaster.

Despite that it was honestly one of the nicer prisoner-of-war camps on either side — though given that your competition is Andersonville, that’s not saying very much. Prisoners were given one meal a day, though it was rarely filling. Fresh water was hard to come by, since most sources were fouled by mud or effluvia from the latrines. Indeed, most of the camp was a giant mud pit that would put Woodstock to shame. Even worse was the dungeon, where prisoners condemned to death were chained hand and foot, sometimes even tethered to a 60 pound iron ball like they were in a cartoon.

Though the Confederates moaned about starvation at least they were being fed, which is more than can be said for prisoners elsewhere. The postal service was excellent even if censors were going through everything with a fine-toothed comb. There was even a well-stocked prison library courtesy of the Young Men’s Christian Association.

What Beall realized as he studied Johnson’s Island was that the qualities that made it an attractive location for a prison also made it a high risk for a massive prison breakout. The small number of guards could be easily overwhelmed by desperate prisoners, and the remote location far behind the battle lines would make it hard for reinforcements to arrive in a timely fashion.

What few reinforcements the camp could call on, though, were formidable indeed: the USS Michigan, the country’s first iron-hulled warship, a 582-ton vessel with 15 guns. It had been left to guard the Great Lakes because it was too big to fit through the Welland Canal and join other Union vessels on the blockade. Mind you, it couldn’t be everywhere at once and was responsible for a territory that stretched from Buffalo to Duluth. Fortunately it didn’t need to be everywhere at once, and spent most of its time plying the waters of Lake Erie.

Beall’s plan to deal with the Michigan was simple: capture it, which he figured could be done by a small force of pirate commandoes. Once they established control of the ship the Great Lakes region would be defenseless. The Michigan‘s guns would be used to free the prisoners on Johnson’s Island, who could either escape to Canada or form an army that would liberate other prisoner-of-war camps and create havoc. Then it would go on to destroy Union commerce by shelling canals and ports from New York to Minnesota.

It was a bold plan, even if it wasn’t exactly a new one — a Lt. William H. Murdaugh had proposed the same thing about a month earlier.

Alas, the Confederates were not yet in a place where they were willing to back such a plan. Piracy and subterfuge still seemed ungentlemanly. Jefferson Davis was also worried that military operations launched from Canada might ruin the country’s uneasy relationship with Great Britain and endanger the delivery of several ironclad warships currently under construction in Liverpool.

Beall’s proposal was shot down, but the higher-ups liked his moxie.

Chesapeake Bay

So they did the next best thing: they made him a pirate.

In March 1863 Beall was made an Acting Master of the Confederate Navy and given leave to assemble a group of privateers and irregulars to spread havoc in the Chesapeake Bay. (What does it say that a consumptive with one lung was unfit for regular infantry service but fit to be an acting master? Either nothing good about the Confederate Navy, or that standards had slipped a lot in two years.)

His first few operations were flashy but did little significant damage. He cut a submarine telegraph cable; he destroyed the Cape Charles Lighthouse at the mouth of the Chesapeake; he captured a small gunboat and a few fishing scows. He graduated to the rank of major nuisance when he began targeting transport ships out of Baltimore carrying war materiel, and captured one with a cargo worth about $200,000.

The Union couldn’t have that, so in October it put together a special task force to hunt down the privateers. On November 10 they literally caught Beall and his men napping, clapped them in irons, and dragged them to Fort McHenry.

On the prison transport, Beall showed a flair for the dramatic, rising up, rattling his shackles, and trying to rally his men to riot. They declined to do so, and he accused them of being “dastardly cowards.”

He kept up the dramatics in solitary confinement, refusing to allow the guards to remove his irons for the regular rest and exercise he was entitled to. “No! Let them alone! Until your Government sees fit to remove them!” He kept up the act for 42 days, before the government just unshackled him and shoved him into the general population.

Beall was returned to the Confederates in a prisoner swap on May 5, 1864. He returned to a very different Confederacy, one that was now willing to try any plan, no matter how outlandish, that might change the course of the war.

His old proposal was given the green light.

John Wilkinson’s Raid

What the higher-ups didn’t tell him was that someone had already tried his plan, and failed.

While Beall was off playing pirate, someone had revived Lt. Murdaugh’s original proposal. Lt. John Wilkinson of the blockade runner Robert E. Lee was tapped to lead the raid, and he was given fifteen men to make it happen. His only explicit instructions were that he should not violate Great Britain’s neutrality. Wilkinson didn’t see how that would be possible, so he decided he would just do whatever he could and let the higher-ups smooth over any difficulties.

Wilkinson and his men left North Carolina on October 7, 1863. They snuck through the Union blockade, sailed up to Halifax, then made their way down the St. Lawrence to Montreal. There they met with escaped prisoners-of-war who had been through Johnson’s Island, who gave them as many details as they could about the prison and its layout.

Unfortunately, while Wilkinson was casing the joint, the Union got word that something was up. They responded by moving the USS Michigan out of its usual berth in Erie and sending it to Sandusky, where it could quickly respond to any breakout attempt. Now Wilkinson needed a plan to deal with the warship. The best one he could come up with was to hijack a civilian vessel, ram the Michigan in a way that made it all look like an unfortunate accident, and then try to take it over in the ensuing confusion.

It was a technique that had been successfully used to capture transports in the Chesapeake, but no one had actually tried it on a warship yet. Wilkinson figured he would need a lot more men to pull it off, and began actively recruiting from the Confederate expatriate community in Montreal. At least some of whom, it turned out, were Union double agents.

The raiders assembled near St. Catherine’s on November 12, 1863 to start their operation. As they were assembling they learned that the authorities were on to them. Governor-General Monck of Canada had issued orders to arrest anyone who might violate British neutrality. American Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton had put all military facilities on the Great Lakes on high alert.

Wilkinson saw little point in proceeding; noting “There was a possibility of a successful issue to this enterprise, but not a probability.” He canceled the raid, and sent everyone back home.

Bennet G. Burley

Beall either didn’t know or didn’t care about Wilkinson’s failed operation. He was just happy to be back in the thick of things. He made his way to Toronto and began assembling a crew of his own… which included his right-hand man Bennet G. Burley.

Burley was a Scotsman, the son of a master mechanic with pretensions of being an inventor. In 1860 he ran away from home to become a soldier-of-fortune, first fighting with Garibaldi for a united Italy, and then working for the better-paying Papal Guards against Garibaldi.

In 1861 Burley arrived in New York and tried to sell the United States Navy plans for a torpedo his father had designed, but the Navy was not interested. Then he went south to Richmond and tried to sell it to the Confederate Navy. They accused him of being a spy and threw him in jail, but freed him on the condition he work on the torpedo project. The torpedo was tested once on a warship in New York Harbor but failed to explode.

When Beall was recruiting misfits for his little band of Chesapeake pirates, Burley was one of his first recruits. He had not been captured with Beall and the others because he had been using a sick day. He had been captured a few months later while trying to test out his torpedo design on a few Union transports.

Burley was sent to Fort Delaware, a tiny little rock in the middle of the Delaware River about six miles south of New Castle. He escaped by swimming through an open sewer into the (not much cleaner) river, where he hopped on a fishing boat that took him to Philadelphia. From there he made his way to Toronto, where he was reunited with Beall.

Eventually Beall put together a crack team of twenty men. He still had an enormous problem: what to do about the USS Michigan. Like Wilkinson before him, he concluded that he just didn’t have the manpower to take it in a straight-up fight; he would be outnumbered more than 5:1. There had to be a better way to take it.

Charles C. Cole

Enter Charles C. Cole.

Cole had recently introduced himself to spymaster Jacob Thompson in Toronto. He claimed to have an incredible pedigree: he had been a captain in the Confederate Army under Nathan Bedford Forrest; he had been captured then escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp; he switched services and became a lieutenant in the Confederate Navy; and then he somehow wound up in Canada with no way to return home.

Thompson had no way to verify any of these claims, but it’s not like he was the type to check references anyway. As we have previously established, he was easily impressed and extremely gullible.

In July 1864 Thompson introduced Cole to Beall as the secret agent who would help him take down the USS Michigan through subterfuge. The two men then made a brief reconnaissance of Sandusky, accompanied by Lt. Bennet H. Young (who was concurrently working for Capt. Thomas Henry Hines as part of the Great Northwestern Conspiracy).

A few weeks later Cole moved to Sandusky and took lodgings at the West House hotel. His cover was that he was a retired executive from the Mt. Hope Oil Company of Philadelphia, looking to have a good time. Now, you might think his ability to have a good time was crippled by the fact that he also brought along his wife Annie, but she spent most of her time shuttling back-and-forth across the border delivering messages to Cole’s co-conspirators, so she was rarely around.

Cole quickly became known around town as:

…a dashing young “swell”… whose prodigality in expenditure attracted the cupidity of the citizens in Sandusky, while his fine wines and costly dinners won, with still greater rapidity, upon the United States officers in the vicinity. (The Memoir of John Yates Beall)

He was spending money as fast as Thompson could send it. He spent a small fortune on a yacht, a fast team of horses, and more liquor than seemed entirely reasonable. No expense was spared in pursuit of his goal: to make friends with the officers of the USS Michigan.

Cole focused his efforts on two key officers: Captain John C. Carter and the ship’s engineer. He made some friendly overtures, and just for good measure threw in all the whiskey and cigars Thompson’s money could buy. Eventually he was invited to tour the ship, then allowed to visit Johnson’s Island and converse with officers being held there (and also slip them warning of the escape plan through slips of paper rolled into cigars).

It was a good start, but it wasn’t enough. Capt. Carter remained distant, and while the engineer seemed awfully friendly he was only one man. Cole realized his original plan to bribe them just would not work. So he would have to incapacitate them somehow.

A new plan began to take shape.

Cole would throw a lavish banquet, invite the Michigan‘s crew to join him, and ply them with drugged champagne until they passed out. The Michigan would have only a skeleton crew left on board and would be stuck in port thanks to some minor sabotage courtesy of the ship’s engineer (who turned out to be eminently bribable after all). That would make it easy pickings for Cole and other local Copperheads.

Once Cole had control of the Michigan he would send word to Beall and his men, who would be waiting nearby in a hijacked steamer. They would swoop in, crew the ship, and train its guns on Johnson’s Island. The prisoners would be freed, and then the Michigan could spread terror along the Great Lakes for a week or two before Beall scuttled it and retreated to Canada.

It seemed foolproof. The operation was scheduled for September 19.

The Philo Parsons Incident

The Philo Parsons was one of the largest steamships plying the waters of Lake Erie at the time. On September 18, while the ship was tied up for the night in Detroit, owner Walter O. Ashley was approached by Bennet G. Burley.

Burley booked passage for the next day, then politely asked if the Philo Parsons could make a brief stop at Sandwich, on the Canadian side of the Detroit River, to pick up a few of his friends. He made it seem like this would be a favor for one of the men, who was lame and had trouble getting around. Ashley agreed, but noted he was on a tight schedule. He was not going to tie up in Sandwich, only touch the dock; Burley’s friends would have to be ready to jump the gap. Burley agreed.

On September 19, the Philo Parsons left Detroit with Burley aboard. A short time later it touched the dock in Sandwich and three men came on board. One of them was John Yates Beall. Ashley and Captain Sylvester Atwood were immediately suspicious. Burley had earlier described Beall as lame, but now he seemed to be anything but. They kept their mouths shut, though.

The ferry proceeded to Amherstberg to take on twenty five more passengers. Sixteen of them were Confederate agents, who were carrying a dilapidated steamer trunk bound securely with ropes. Ashley and Atwood did not like the look of the new arrivals either, but figured they were just “skeedaddlers” (or, Union deserters).

From Amherstberg the Philo Parsons steamed down to Middle Bass Island. There Captain Atwood took his leave — his family lived on the island, and he was going to spend the night with them. Control of the vessel was turned over to first mate De Witt C. Nichols.

The next stop was Kelley’s Island, where several more passengers came on board. A messenger from Cole was supposed to have been among them, but was not. Beall seemed unconcerned.

The Philo Parsons left Kelley’s Island at 2:00 PM. Once it was well clear of the island, Beall gave the signal. The Confederates opened their trunk and armed themselves with the hatchets and revolvers inside. As the passengers recoiled, Beall leveled his revolver at Ashley’s head and declared, “I take possession of this boat in the name of the Confederate States! Resist at your peril!”

Burley rounded up the crew and then pointed at the ladies’ cabin. “Get into that cabin or you are a dead man,” he said, then began counting slowly to ten. The crew quickly complied. Mostly. When pilot Michael Campbell was ordered into the hold by one of the raiders, he told them to go to hell. A quick shot between Campbell legs produced rapid compliance.

Ashley knew there was little point to resistance, and only begged the Confederates to please not scuttle his ship. Beall snorted that Union soldiers would not be so kind: “If you were a United States officer and had seized one of our boats, you would probably destroy it.”

Despite that he was pretty respectful. Civilians were allowed to keep all their money and property; even one who was purportedly carrying some $80,000 (or maybe just $80). He did confiscate some $100 of the ship’s money as his prize, and toss all the cargo in the hold over the side.

This took about half an hour, and during that time the Philo Parsons had been drifting aimlessly on the current. When Beall finally took control he turned it back towards Sandusky, but soon realized he did not have enough fuel on hand to complete the trip. He turned back to Middle Bass Island for wooding.

As soon as the ship touched the dock on Middle Bass, Confederates began frantically loading as much fuel as possible. When the woodlot owner and his employees came down to help, the Confederates fired a few shots to drive them off. That drew the attention of Captain Atwood, who came down to see what was going on and was taken captive.

While Beall debated his next move another steamship, the Island Queen, came alongside them to refuel. The Confederates immediately swarmed the deck only to discover that its passengers included some twenty five soldiers from the Ohio Volunteer Infantry on their way to Toledo to be discharged. Fortunately, they weren’t armed, but they did put up some resistance. Shots were fired, another man took a hatchet to the head, others were knocked down or pistol whipped. Henry Haines, the engineer, couldn’t hear the Confederates ordering him to surrender over the roar of the engines and was shot in the gut when they finally decided to just “shoot the son of a bitch.”

Beall had far too many prisoners now. He made the passengers and crew swear an oath not to call for help, then put them ashore into the care of Captain Atwood. To help ensure Ashley’s compliance, he returned most of the money that he had previously taken (though Burley kept $20 for himself).

Captain Orr of the Island Queen and other prisoners who would not swear the oath were thrown into the hold of the Philo Parsons. Then the two vessels were lashed together and set off.

As soon as the Philo Parsons was out of sight the passengers violated their oath. They commandeered some rowboats and made their way to Put-In-Bay on South Bass Island to spread the word. That attracted the attention of resident John Brown Jr. and his brother Owen Brown. They hadn’t fought at Harper’s Ferry just to let some Confederates spread mayhem in their own back yard. They called out the local militia, handed out guns and ammo from their personal store, and even readied a “victory cannon” that had been left on the island by Oliver Hazard Perry after the War of 1812. Then John and several others rowed over to Sandusky to warn others, though they arrived too late to make a difference.

Meanwhile, Beall stripped and scuttled the Island Queen and set her adrift. She drifted for five miles, struck a reef, then sank.

At 10:00 PM the Philo Parsons took up position opposite Marblehead Light at the entrance to Sandusky Bay. In the moonlight they had a clear view of the USS Michigan and patiently waited for Cole’s signal: a flare that would be fired from its deck.

It never came.

What Happened?

Turns out the Union had been on to the plot for some time.

On September 17, a double agent named Godfrey Hyams delivered intelligence to Lt. Col. Bennet H. Hill, Assistant Provost General of Michigan, that an attack on the USS Michigan was imminent, that several officers had been bribed by Cole, and that he intended to drug and incapacitate the others.

Hill promptly passed that information off to Capt. Carter, who had been suspicious of Cole the entire time. The spy had not bothered to hide his Confederate sympathies at all, and spent most of his time partying with Sandusky’s leading Copperheads. Carter had even assigned one of his gunners to keep an eye on Cole, and that gunner tailed him as far as Windsor, Ontario where he was spotted meeting with exiled Copperhead politician Clement Vallandigham.

Hyams and Carter weren’t the only ones who knew something was up. A counterspy posing as a patent medicine salesman on Johnson’s Island said the prisoners were seemed to think they would be escaping very soon. Even a local debutante Cole was trying to woo (when his wife wasn’t around) was secretly spying on him and reporting his actions to the Union officer she was actually sweet on.

Cole, of course, was oblivious to all of this.

Back in Sandusky he put out a lavish spread at his hotel, hoping to lure officers and enlisted men off the Michigan so there would be only a skeleton crew. He was surprised when only one man showed, Ensign James Hunter. Hunter had a few drinks and began complaining that Capt. Carter had refused to grant anyone leave to attend the party. Then he suggested that the captain might be more amenable if Cole went to the Michigan and made his case in person. Cole thought that was a great idea and grabbed his coat.

The moment he set foot on deck he was immediately arrested.

The silver-tongued spy tried to talk his way out of it by offering to buy a round of whiskey for everyone on the boat. Instead they frisked him and found bank drafts drawn on Montreal banks that were known for laundering Confederate money. And also his commission as a major in the Confederate Army. Whoops.

While Cole was hauled off to jail, Beall sat on board the Philo Parsons and waited for the signal. And waited, and waited, and waited. Eventually, he decided to proceed anyway.

His crew revolted. First the pilot said it was too dangerous to navigate the bay at night, but Beall didn’t care. Then the rest of the men also chickened out, with only Burley standing with his captain. He tried to sway them with more dramatics, pointing that “immortal glory” was theirs for the taking and the only disgrace would be failure to act, but no dice. Realizing he was hopelessly outnumbered in more ways that one, Beall agreed to the demands to turn back. But first he made all of his men sign a formal declaration that they were cowards and absolving him of blame for the operation’s failure.

The Confederate flag was raised and the Philo Parsons was turned back toward Detroit. Beall hoped he would stumble across some Yankee clippers to plunder on his way back, but no such luck. Just above Malden they sent what little booty they had seized over to the mainland. Captain Orr and the other prisoners were set ashore on Fighting Island. The Philo Parsons docked at Sandwich and was scuttled. The crew disappeared into the night.

In the morning Capt. Carter and the USS Michigan went in search of the raiders they had been expecting, but could not find them. They made it as far as Detroit before turning back to Sandusky.

The Trial of Charles C. Cole

Charles C. Cole’s life story quickly unraveled. It turned out that he was not only a spy, but a liar and con man. He had never served under Nathan Bedford Forrest; he had never escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp; he had never been a lieutenant in the Confederate Navy. He wasn’t even married to the woman he was passing off as his wife; she was just Annie Brown, a prostitute he had hired to be a courier (a courier with benefits, presumably).

Cole was just a Pennsylvania boy who had run off to join the Confederate Army but had never been more than a foot soldier. He had been captured in Tennessee and paroled with the understanding that he would return to Harrisburg and spend the rest of the war living with his parents.

After his arrest, Cole began ratting out everyone who had helped him. He named several local Copperheads as well as prominent and respected members of Sandusky’s business community, many of whom seemed to have no idea what he was going on about.

Four of the men went to trial: Charles C. Cole, his actual co-conspirator John B. Robinson, architect J.B. Merrick and businessman Louis Rosenthal. Cole immediately flipped to provide state’s evidence against the others, so Merrick and Robinson went on trial first. The problem was that Cole’s testimony was the only evidence against them, and it was so unbelievable that the defendants were found not guilty after only thirty minutes of deliberation.

The authorities held on to Cole but eventually decided he was too untrustworthy to use as a witness against Rosenthal or others. He was tried by a military commission and sentenced to hang as a spy.

At this point Annie Brown came back on the scene, returning from Toronto with a letter from Jacob Thompson asserting that Cole was a soldier and not a spy. That got Cole’s death sentence commuted to imprisonment for the duration. Which, ironically, he was sentenced to serve out on Johnson’s Island.

In July 1865 Cole attempted to escape. Only twelve men ever managed to escape from Johnson’s Island, and Cole would not be among their number. A month later he was transferred to Fort Lafayette in New York, where he served out the rest of his sentence. After the war he was quickly forgotten.

The Trial of John Yates Beall as a Spy and Guerrillero

Beall could not handle being betrayed by his men, and retreated to a hunting camp in north Ontario to sulk and lay low. That wasn’t really him, though, and after a few weeks he felt the need to get back into action.

In December 1864 Beall volunteered to work with two other Confederate saboteurs, Lt. Col. Robert Martin and Lt. John Headley. Martin and Headley had just unsuccessfully tried burn down New York City, and now were trying to free Confederate prisoners-of-war being transferred from Johnson’s Island to Fort Warren in Boston by derailing trains. On December 10 and 11 the conspirators crossed over to Buffalo from Niagara Falls and made several unsuccessful attempts to sabotage the train tracks, fleeing back across the border after each failed attempt.

On December 15 they made one final attempt. In the wee hours of the night they placed a few stray rails across the train tracks, but they did not derail their target. Instead the train hit the loose rails and sent them flying about fifty yards. When it came to a stop and soldiers began walking back along the tracks to see what they had struck, The Confederates belatedly realized they had no actual idea what to do if the first part of the plan succeeded, and bolted.

They made their way to the nearest train station, outside Buffalo, and hopped on the next train to Canada. Beall was about to board the train when he realized the youngest member of their group, Pvt. George Anderson, was missing and went back to find him. The two men tried to take a quick nap and wait for the next train, only to be picked up by policemen who were looking for them.

When asked to identify himself, Beall reflexively gave his real name, then corrected himself and said he was W.W. Baker. He and Anderson were then arrested under suspicion of being escaped prisoners from Point Lookout. After hours of intense interrogation Anderson broke and told the authorities the truth, which was corroborated by a diary Beall had hidden in his coat.

When the authorities realized they had Beall in custody, they were over the moon. He was famous. He was sent to New York to be tried before a military commission as a spy and guerilla.

Beall attempted to bribe his way out of jail, offering his jailer $1,000 in gold to set him free. Mind you, Beall didn’t have the gold on him, but swore he was good for it and that had done this sort of thing before. The offer was refused, and Beall was immediately transferred to a more secure holding facility at Fort Lafayette.

His trial began on January 20, 1865. Beall was charged with espionage, with piracy, with attempted sabotage, and with attempted arson for participating in Martin and Headley’s previous attempt to burn New York City. (Which he had not participated in, and was dead set against)

His initial strategy was to delay.

I am a stranger in a strange land; alone and among my enemies; no counsel has been assigned me, nor has any opportunity been allowed me either to obtain counsel, or procure evidence necessary for my defense. I would request that such counsel as I may select in the South be assigned me, and that permission be granted him to appear, and bring forward the documentary evidence necessary for my defense. If this cannot be granted, I ask further time for preparation.

He had hoped his cellmate, Gen. Roger A. Pryor, would be able to serve as his defense attorney. This was refused, on the basis that a prisoner-of-war should not serve as counsel for an accused spy, and he was assigned a public defender. A very good one, actually: James T. Brady, who had previously defended Congressman Daniel Sickles after he shot U.S. District Attorney Philip Barton Key.

Brady’s defense strategy was to argue that Beall was a regular soldier acting in accordance with the laws of war, and that any evidence he was a spy was spotty at best. He gave a very passionate and learned speech on the subject. He even produced documents backing up his argument, including affidavits from the Secretary of the Confederate Navy that Beall was on active duty, and from Jefferson Davis himself that the Philo Parsons incident was a authorized military operation.

Alas, this evidence was being presented to Maj. General John A. Dix, who would have none of it. He knew a spy when he saw one.

On February 18 the military commission found Beall guilty of all accounts except attempted arson, of which he was provably innocent. He was sentenced to hang.

Brady appealed the conviction, of course. He sent President Lincoln a copy of the trial transcript with a handwritten note from Beall: “Some of the evidence is true, some false. I am not a spy or guerrilero. The execution of the sentence will be murder.” Some ninety members of Congress even signed a petition begging for clemency in the case, including notable Republican die-hards like Thaddeus Stevens and future president James A. Garfield.

Lincoln, who was normally a soft touch, would not be moved and deferred to the judgment of General Dix. Dix would also not be moved. He had no love for Confederates, and even less love for spies. Especially spies he suspected of trying to burn down his beloved New York.

John Yates Beall was walked up to the gallows on February 24, 1865 and asked if he had any last words. He said:

I protest against the execution of the sentence. It is absolute murder; brutal murder. I die in defense of my country. I have nothing more to say.

And then he was hung by the neck until he was dead.

During his incarceration and trial Beall kept a diary, which was later expanded into a “memoir” and published posthumously. It is a masterclass in self-pity and shifting the blame to others, and is hard to take seriously.

It sold pretty well, though.

The Trial of Bennet G. Burley

Despite the loss of his most capable naval man, Jacob Thompson was still trying to turn the Great Lakes into an active front for the war.

In October 1864 one of Thompson’s proxies, Dr. James T. Bates, spent $16,500 to purchase the steamer Georgian. Ostensibly the ship would be used to shuttle timber across the Georgian Bay. In actuality, the Confederates planned to refit the vessel with a bow ram and several artillery pieces and then send it to sink the USS Michigan.

When Bates took possession of the Georgian at Port Coulborne, American authorities began wondering why it had been purchased for a price far beyond its actual value, at the end of the season. Double agent Godfrey Hyams soon confirmed their suspicions. Bates realized that he had been rumbled, packed the hold full of lumber, and steamed off to Sarnia, Ontario. He was trailed by the USS Michigan the entire way, and was boarded in both Detroit and Sarnia by customs officials who found nothing out of place.

However, the authorities did intercept a crate labeled “potatoes” that was being shipped to the Georgian, but which actually contained munitions. They tracked it back to a familiar face: Bennet G. Burley.

After the Philo Parsons incident, Burley had returned to his first love, inventing. He had set up a laboratory in Guelph and began improving the Confederate formula for Greek fire, trying find a way to use it in cannonballs and torpedoes. Burley was arrested on November 17 and dragged to Toronto in irons.

In a rather novel legal strategy, the United States government attempted to have Burley extradited to Ohio… for the crime of stealing $20 from Walter O. Ashley, the owner of the Philo Parsons. Burley’s defense counsel argued that the taking was not a criminal act but an act of war beyond the scope of the criminal courts. The argument failed, largely because the British government was getting fed up with Confederates abusing their neutrality.

Back in Scotland, Burley’s father attempted to hold up his son’s extradition through diplomatic channels. That worked for a while, not forever. Burley was extradited to Ohio and tried for robbery. The trial took forever, but the evidence against Burley was weak and the jury deadlocked. A retrial was scheduled, but Burley did not stick around to see how it would turn out. Instead he decided to jump bail, leaving behind a Bible on his bedside table with a short note stuck inside:

Sunday:

I have gone out for a walk.

Perhaps I will return shortly.

B.G. Burley.

He did not return. He fled back to the United Kingdom and eventually became a celebrated war correspondent under the nom de plume of “Burleigh” (spelled all posh with an E-I-G-H). He had a pretty crazy life, including serving as Rudyard Kipling’s personal escort during the Boer War, but those tales can wait for another day.

As for the Georgian, it eventually got iced in for the winter. Thompson realized he would never have a chance to covertly arm it and tried to sell it instead. Before he could do that the vessel was seized by the British government on April 6, 1865. (And a week later the whole thing was moot anyway because the war was over and Lincoln was dead.)

Aftermath

And that would be that, if it wasn’t for a story that began circulating years after the war.

It was said that on the night before John Yates Beall’s execution, President Lincoln was visited by an old college buddy of Beall’s who eloquently made the case for lenience. It was said the case was so persuasive that Lincoln was moved to tears and swore he would pardon Beall first thing in the morning.

Lincoln’s word proved to be worthless in the cold light of day. Secretary of State William H. Seward talked the president out of issuing the pardon by suggesting that it would destroy popular support for Republicans across the North. The execution went on as scheduled, and Beall’s old college buddy swore he would have his revenge.

The name of that buddy? John Wilkes Booth.

Great story, isn’t it?

It’s not true. Beall and Booth were not old college buddies. There’s a possibility they may have met while serving in the Virginia militia in 1859, but no definitive proof. They never corresponded or spoke of each other, and Booth’s diaries do not mention Beall and unambiguously state that he was motivated solely by his love of country. The whole tale seems to have been concocted by newspaper editor Mark M. Pomeroy to sell more copies of Pomeroy’s Democrat.

That’s too bad, because it would have made a far better ending to today’s episode than this anticlimax.

Connections

Johnson’s Island, of course, first appeared last episode (“Rapscallions 1: Patience is Sour”) when General John Hunt Morgan and his men were imprisoned after the failure of their July 1863 cavalry raid. You might remember that they ate the commandant’s dog before getting transferred to the Ohio State Penitentiary.

Though the Philo Parsons incident was undoubtedly the most exciting part of its service record, the USS Michigan had a long and storied career. After the war it was primarily a training vessel where young officers could get their first taste of command. Those officers included Lt. Commander Charles Vernon Gridley, who became a tragic hero during the Spanish-American War. (“He Fired When Ready”)

The first plan to capture the USS Michigan was abandoned because the Confederacy worried that operations in Canada would endanger the delivery of several ironclad rams being built in England. They should have just gone ahead with it, because those rams were seized by the British when the United States complained that their delivery would violate neutrality laws. The Confederates were forced to adopt a strategy of refitting commercial vessels as pirate ships, the last of which was the CSS Shenandoah (“The Sea King”).

Bennet G. Burley made a daring escape from Fort Delaware, which is located in the Delaware River right between the unimaginatively named Delaware City, DE and Finn’s Point, NJ — the heart of what was once the colony of New Sweden (“Nya Sverige”).

The Detroit River has always been a weird flashpoint for conflicts between the United States and Canada. Not only was it a hotspot of activity during the Patriot War (“Dangerous Excitement”) it also so action during the War of 1812 and was the final home of “The White Savage” Simon Girty (“He Whooped to See Him Burn”).

Sources

- Beall, John Yates. Memoir of John Yates Beall: His Life; Trial; Correspondence; Diary; and Private Manuscript Found Among His Papers, Including His Own Account of the Raid on Lake Erie. John Lovell, 1865.

- Bell, John. Rebels on the Great Lakes: Confederate Naval Commando Operations Launched from Canada, 1863-1864. Dundurn, 2011.

- Gora, Michael (editor). Lake Erie Islands: Sketches and Stories of the First Century after the battle of Lake Erie. Lake Erie Historical Society, 2004.

- Harris, William C. Confederate Privateer: The Life of John Yates Beall. Louisiana State University Press, 2023.

- Horan, James D. Confederate Agent: A Discovery in History. Pickle Partners, 2015.

- Jones, Virgil Carrington. The Civil War at Sea, Volume 3: The Final Effort. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1962.

- Karle, Ted. “More Photographs of the U.S. Steamer Michigan.” Military Images, Volume 30, Number 3 (September 2008).

- Keehn, David C. Knights of the Golden Circle: Secret Empire, Southern Secession, Civil War. Louisiana State University Press, 2013.

- Lawson, John D. (ed.). American State Trials (Volume XIV). Thomas Law Book, 1923.

- Markens, Isaac. President Lincoln and the Case of John Y Beall. Self-published, 1911.

- Mayers, Adam. Dixie and the Dominion: Canada, the Confederacy, and the War for the Union. The Dundurn Group, 2003.

- Sanders, Charles W. While in the Hands of the Enemy: Military Prisons of the Civil War. Louisiana State University Press, 2005.

- Schultz, Duane. The Dahlgren Affair: Terror and Conspiracy in the Civil War. W.W. Norton, 1998.

- The Trial of John Y. Beall as a Spy and Guerrillero by Military Commission. Appleton and Company, 1865.

- Tidwell, William A. April ’65: Confederate Covert Action in the American Civil War. Kent State University Press, 1995.

- Wilkinson, John. The Narrative of a Blockade Runner. Sheldon & Company, 1877.

- Woodford, Frank B. Father Abraham’s Children: Michigan Episodes in the Civil War. Wayne State University Press, 1961.

- “Ask Infoser.” Warship International, Volume 45, Number 4 (2008).

- “Comments and Corrections: Ask Infoser.” Warship International, Volume 54, Number 4 (December 2017).

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: