Run the World

who really deserves the title of "America's first woman governor?"

A few years ago, my brother and I took a vacation in the great state of Texas. We’re both huge nerds, so our trip included a lot of historic sites and museums. We hit the San Antonio Missions, the Johnson Ranch, the Dr. Pepper Museum and Free Enterprise Institute, the Sixth Floor Museum, and, of course, the Texas State Capitol.

If you’ve never been to the Texas State Capitol, go! It’s a pretty neat building. Since the governor and legislature only work for a few days each session, you can have access to a surprising amount of the building. You can wander onto the floor of the House of Representatives. You can sit at the table where the governor signs and vetoes legislation. And you can marvel at the rotunda, which is a good 15′ higher than that of the U.S. Capitol, and ringed by portrait of the state’s governors.

One portrait the tour guides make sure to show off is that of Miriam Amanda Ferguson, the first elected woman governor in United States. Now, if you’ve ever taken a women’s studies course, you’re probably scratching your head. Wasn’t Wyoming’s Nellie Tayloe Ross the first woman governor in the United States? That’s right! Ross was sworn in about twenty days before Ferguson was.

Ah, the tour guides will say, but both women were actually elected on the same day in November. Since Texas is on Central Time and Wyoming is on Mountain Time, well, Mrs. Ferguson was actually elected an hour before Mrs. Ross. Therefore, they will snarkily declare, Texas rightly deserves the honor of “first woman governor,” but in the absence of official recognition, they’ll settle for the pedantic distinction.

Then the tour guide will move you along to the next stop before you can ask any questions. But as my group shuffled along I happened to notice a portrait hanging a few spaces to the left of Miriam Ferguson. A portrait that led me to do some digging to see what was really going on with this first woman governor thing. And let me tell you, it’s not pretty. On either side.

So, let’s do this thing. A no holds barred, three round bout to see who truly deserves the title of America’s first woman governor. Woo!

Round 1: The 1924 Gubernatorial Elections

So, here’s the point where the Bechdel test goes out the window, because in order to understand the elections of Miriam Amanda Ferguson and Nellie Tayloe Ross, you have to talk about their husbands.

Texas

In the case of Miriam Ferguson, that would be James Edward Ferguson. Jim Ferguson was a good ol’ boy, country lawyer and banker from Temple, Texas. Oh, and the Twenty-Sixth Governor of Texas.

He had run in the 1914 election as “Farmer Jim,” a populist champion of the common man and an outsider who wasn’t beholden to the political machine. In actuality he was just a shameless opportunist who used politics and graft to increase his fortune and personal influence. He had an uncanny knack for throwing just enough red meat to his constituents to keep them happy, without making any concessions that would upset the real power brokers. It worked well enough to get him elected, and re-elected in 1916.

But Farmer Jim made one key mistake: he messed with Texas. The University of Texas, that is. Back then it was thoroughly Republican, elitist, and anti-Ferguson. So Jim attacked the University in the press every chance he could, cut all of their state funding, and tried to force out one of the regents.

His heavy-handed approach caused a backlash from UT alumni that actually got him impeached. (They threw in some charges related to his financial mismanagement of state funds, and some suspicious “private loans” that were clearly bribes, but really, it was all about the University.) In the end, Farmer Jim was convicted 25-3 by the state Senate and barred from holding any future office of honor, trust or profit in the great state of Texas.

That didn’t stop him from trying to run for governor in 1918, president in 1920, and senator in 1922. Each time he failed to make it out of the Democratic primary, sparing the party the potential embarrassment of fielding a candidate who couldn’t actually go on the ballot in the general election.

When Jim tried to run for governor again in 1924, the Democrats finally put their foot down and refused to put him on the ballot. So Jim responded by filing paperwork announcing Miriam’s candidacy for governor.

It wasn’t actually the first time he’d tried this trick. He’d done the exact same thing in 1922 when the Democrats had balked at putting his name on the ballot. But in that race, the party had relented on the hair-splitting technicality that United States Senator wasn’t a “state office,” and Jim had withdrawn Miriam’s name from consideration. This time, though, they didn’t budge, so Miriam entered the race.

Miriam Amanda Wallace Ferguson had been the daughter of a wealthy farmer, and married Jim back when he was a poor country lawyer joining every fraternal society that would have him as a member. To our modern sensibilities Miriam seems like a pleasant non-entity, but at the time she was practically the ideal of a Texas wife: a modest woman who ran a tight house, lived for her children, kept her opinions to herself and unquestioningly supported her husband.

Miriam was also thoroughly uninterested in politics. She had been against woman’s suffrage, the the Nineteenth Amendment, and was on the record as saying, “I prefer that men shall attend to all public matters.”

Her primary campaign was an interesting one. In July the Fort Worth Record-Telegraph ran a comparison of the nine Democratic hopefuls. Miriam’s platform was the shortest and least detailed, relying on generic statements like “reduce waste” and “cut expenses” and “restore Texas to the place she has held in the galaxy of states.” (#maketexasgreatagain)

Well, she did have a few unique appeals. First: clearing her family name.

“I have a little bright-eyed grandson that I love dearer than life itself. If somebody wants to point the finger of scorn at him and say, ‘Your grandfather was impeached by the Senate of Texas,’ I want that grandson to be able to say: ‘Yes, and as a rebuke to that impeachment that denied Grandfather the right to go to the people, my dear Grandmother was elected governor.”

Her second appeal was, “Vote for me, and I will do whatever my husband tells me to do.” She was clearly a proxy for Jim Ferguson and nothing more. Jim couldn’t even be bothered to keep up the ruse that she was the real candidate, often using “I” instead of “she” or “we” in the statements he issued as her campaign manager.

Her final appeal was, “Vote for me because I’m a woman.” Jim relished the idea of being involved in a historic first, and thought Miriam could sweep up the votes of women who were happy to finally have a voice in elections but didn’t see themselves as any sort of feminist. So he created an image of wifehood and motherhood for Miriam that was so bland and inoffensive that it verged on the saintly. When some wag noticed that Miriam’s initials were “M.A.”, Jim popularized the nickname “Ma Ferguson” and the catchy campaign slogan “Me for Ma.”

None of the nine candidates in the August primary managed to win the nomination outright, but Miriam managed to snag enough of the vote to qualify for the three-candidate run off a few weeks later.

At this point, Jim made one important change to Miriam’s platform. The leading candidate, Judge Felix Robertson, was supported by the Ku Klux Klan, so Miriam became anti-Klan. Well, sort of. She called the Klan interlopers from Georgia who should keep their noses out of Texas politics. But she also made it very clear that she supported the Klan’s goals 100%, even if she did not support their method their methods. She made her position plain: “A bonnet or a hood.”

Well, it worked. On August 23 Miriam Amanda Ferguson won the Democratic Primary with 90,000 votes. At that point, winning the election was such a sure thing that Jim even ran ads in the papers calling his wife the “governor-elect.”

Though that didn’t stop some people from trying to derail the Ferguson train. San Antonio attorney Charles M. Dickson filed to get an injunction to stop Ma Ferguson from appearing on the ballot on the following grounds directly related to her gender:

- The Nineteenth Amendment only gave women the right to vote in Federal elections, not state elections;

- Even if it did, they still only had the right to vote, but not the right to hold elected office;

- Married women had limited legal rights to execute contracts and enter agreements, which precluded them from executing the duties of governor;

- And finally, since women could not join the military, women could not in any meaningful way be the “commander-in-chief” of National Guard units, which was one of the essential functions of the governor.

It is worth noting that Miriam’s republican opponent, Dr. George C. Butte, found these arguments extremely distasteful and declined to participate in the suit. When it became clear he was going to lose even Dickson backed away fro the suit, claiming his only goal was to clarify some ambiguities in the law rather than directly opposing Ferguson’s candidacy.

With nothing else to write about, Texas papers were forced to run articles about what Ma Ferguson would look like with a bob, whether she would have a cat or a dog in the governor’s mansion, and what kind of appliances she had in her kitchen. She cruised to victory in the November 4 general election, winning 58% of the vote.

Wyoming

Our discussion of the 1924 Wyoming gubernatorial election will go a lot quicker.

Because Wyoming wasn’t supposed to have a gubernatorial election in 1924. At the beginning of October, popular Democratic governor William B. Ross died unexpectedly of appendicitis, and a special election was called to fill the office the remainder of his term.

This put the state Democratic party in a bind. Wyoming was a thoroughly Republican state, and none of the party’s rising stars had a fraction of the late governor’s popularity or name recognition. So in desperation, they turned to the only potential candidate who did: his widow, Nellie Tayloe Ross, a small town socialite and former school teacher.

Nellie was not terribly excited by the idea, but she was in a bind herself. Her husband’s political ambitions had led their family to live far beyond its means. Without a steady source of income, she would have no way of paying off the mountains of debt she’d just inherited.

And the more Nellie thought about the prospect of running for governor, the more attractive it seemed. “Governor of Wyoming” was certainly a guaranteed steady income for at least two years. She and her husband had been intellectual equals, and she’d always been very involved in his political career. Maybe she’d “unconsciously absorbed” enough of his political craft to muddle through with the help of his aides. So she accepted the party’s nomination.

Though she also made it very clear they shouldn’t expect much.

“While I believe as a general proposition that most public offices can be filled by women quite as satisfactorily as men, a public career for myself never previously had an appeal. I appreciate far beyond my ability to express the honor conferred upon me by unanimous vote of the delegates, but I regard it as a tribute to my departed husband, giving further substantial evidence of the high esteem in which he was held by the people of this state.”

Nellie’s whole platform amounted to, “Vote for me, and I’ll carry on my husband’s work.” She didn’t even bother to campaign, using her mourning period as a shield. Her precious few public appearances were appallingly terse: her acceptance speech at the nominating convention was less than 400 words, and a brief message aimed at Wyoming’s women was only 300 words.

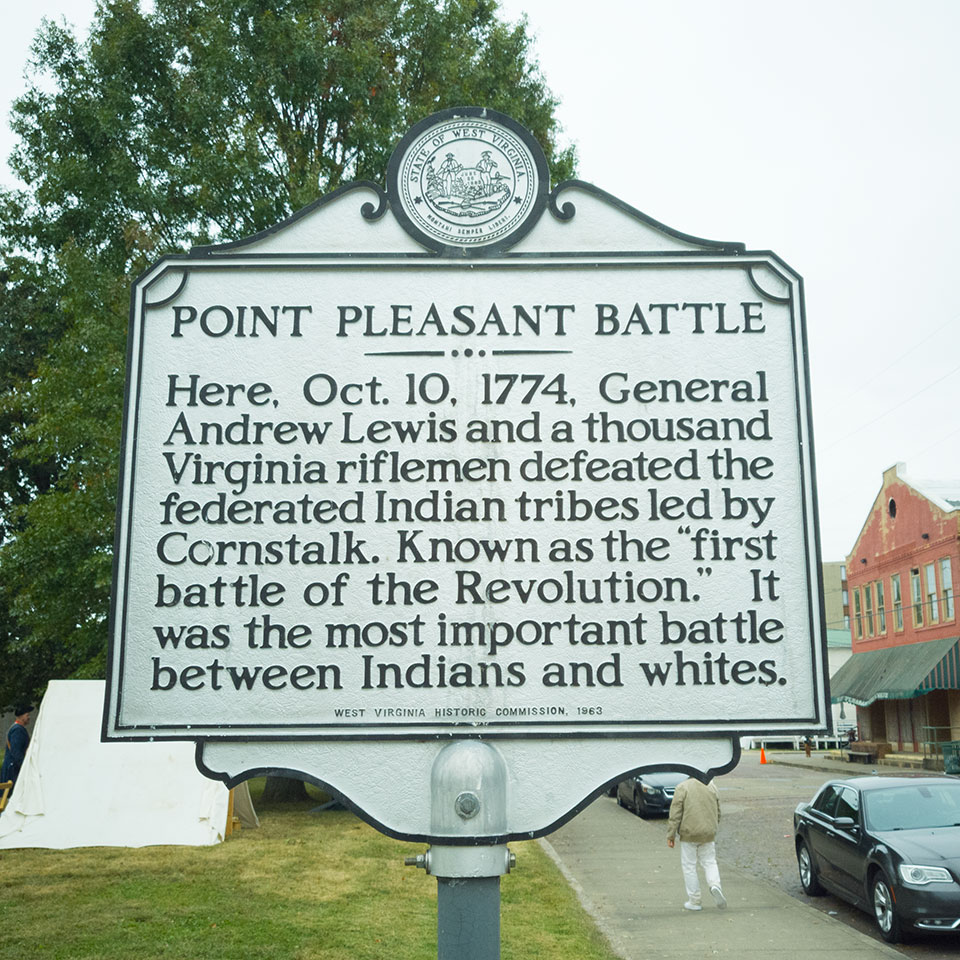

William’s friends and allies picked up the slack. They aggressively reminded voters about Wyoming’s history of women’s rights — it had been the first territory to extend the franchise to women — and pushed the idea that the Equality State needed to “beat Texas” to the first woman governor.

It wasn’t the greatest appeal, but it worked. On election day Nellie defeated her opponent, Eugene J. Sullivan, by some 7,000 votes. Sullivan was gracious in defeat, and his concession speech managed to be uplifting, conciliatory and belittling at the same time:

“Mrs. Ross has a man-sized job and it is not proper that we should stand away looking on, letting her conduct the battle alone. This little lady, now your governor, should be granted your complete unforced support.”

Scoring

Scoring this round is not going to be easy.

On one hand you have a candidate who is just a proxy for her corrupt husband. On the other, you have a candidate who embodies one of my least favorite political tropes: the widow’s succession. Neither woman was running out of personal ambition, and neither ran anything close to a substantive campaign.

So let’s call this round a draw. On to round two!

Round 2: Accomplishments in Office

Wyoming

Nellie Tayloe Ross was sworn in as Wyoming’s fourteenth governor on January 5, 1925, and was almost immediately plunged into the thick of it. Wyoming’s do-nothing legislature only met for 40 days out of every two years, which meant she only had one shot to present her legislative agenda.

She dropped the ball.

Nellie had a number of strikes against her from the start. She had no practical executive or legislative experience. What little stroke or influence she’d inherited from her late husband had been used up during the campaign itself. And the legislature was solidly Republican.

None of her proposals passed. There was nothing for her to do for the next two years except to manage the daily business of the state.

When the 1926 elections rolled around, the Republicans were far less cordial than they’d been two years earlier. To their credit, they never made Nellie’s sex an issue, but they did decry her as a figurehead for a group of her late husband’s associates and cronies. Which, to be fair, she was. They also attacked her as weak on women’s rights, because she hadn’t even attempted to seat a single woman in any of the state’s appointed offices.

Nellie countered by asking voters to judge her solely on the basis of her accomplishments, which unfortunately were few and far between. As election day neared, she desperately begged voters to re-elect her so no one could say the nation’s first woman governor was a half-term failure.

The emotional appeal didn’t work. She lost her re-election by the slimmest of margins and the Republicans went on to capture every office in the state.

Texas

Down in Texas, Miriam Ferguson was sworn in as the state’s twenty-ninth governor on January 20, 1925. Over the next few months she actually managed to shepherd a number of proposals through the state legislature, most notably outlawing the Ku Klux Klan.

As expected, the First Gentleman held all the real power in the state. Jim Ferguson attended every cabinet meeting and did most of the talking. He even had his own desk inside the governor’s office. One insider noted, “Jim’s the governor, Ma signs the papers.”

The Fergusons immediately returned to their crooked ways, selling pardons and taking bribes and kickbacks in exchange for fat government contracts. That drew the ire of state Attorney General Dan Moody, who nullified the worst examples.

In 1926, an irate Moody decided to primary Ma Ferguson. The Fergusons crowed about their experience, claiming that they offered Texas a great value as “two governors for the price of one.” Moody accurately pointed out that one of those governors was just a puppet, and the other one was the most corrupt politician in state history.

The Fergusons went down in flames in the primary, and Moody went on to become Texas’s thirtieth governor.

Scoring

Scoring for this round seems easy: Nellie Tayloe Ross had no real accomplishments in office, and Ma Ferguson had quite a few. Sounds like an easy Ferguson win. But I’d argue the brazen corruption of the Fergusons offset the few good things they inadvertently managed to accomplish. I’ve got to call this one another draw.

After two rounds, our candidates are even. Sounds like the last round will decide it all.

Round 3: Later Careers

Texas

After leaving office, Miriam Ferguson returned to her life as a wife and homemaker. Which now meant serving as Jim’s proxy candidate every other year.

In 1932 Ma actually managed to win a second term as governor, after running one of the most spectacularly disingenuous campaigns in Texas history. Once again, the Fergusons used their positions to enrich themselves at the expense of the state and were turfed out after a single term. Their abuse of the pardon power was so extensive that Texans amended their constitution to take most of the process out of the governor’s hands.

By 1940 the Fergusons’ act was getting old. They proved to be no match for a new generation of go-getting demagogues like “Pappy” O’Daniel. Seeing the writing on the wall, the Fergusons retired from politics for good. Jim died in 1944, and Miriam in 1961.

Wyoming

After leaving office, Nellie Tayloe Ross supported her family by becoming a lecturer on the Chautauqua Circuit, an organizer for Wyoming’s Democratic Party, and eventually, a full member of the Democratic National Committee and its Director of Women’s Activities.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt installed Nellie as the Director of the U.S. Mint in 1933, partly in recognition of her service to the party, and partly to get her out of the way of Eleanor Roosevelt (who had been working under Nellie for the previous four years and openly coveting her positions). She took the job very seriously, and became the longest serving director fo the Mint, holding the position for the entirety of the Roosevelt and Truman administrations.

She died in 1977 at the age of 101.

Scoring

This is another tough round. Ma won a second term as governor, but she was still a puppet. It’s hard to top “longest-serving director of the U.S. Mint.” So let’s give this one to Nellie.

Final Scoring

That means Nellie Tayloe Ross takes the whole thing. Congratulations, Wyoming! You can still lay claim to the nation’s first woman governor.

Sorry, Texas. I know this would’ve been a feather in your cap, but maybe next time before you push that narrative you should make sure your candidate isn’t a corrupt puppet.

Still, it’s not like Nellie comes out looking great in this battle either. She was also a puppet, though she did have some agency and wasn’t corrupt. What really redeems Nellie is her long and distinguished career of civil service.

So there you have it, folks, the story of America’s first two woman governors. Neither one is exactly the bright shining feminist icon we would have liked to have. But remember what Bismarck said: “Politics is the art of the possible, the attainable — the art of the next best.”

Happy International Women’s Day!

Sources

- Luthin, Reinhard H. American Demagogues: Twentieth Century. Gloucester, MA: Beacon Press, 1954.

- Scheer, Teva J. Governor Lady: The Life and Times of Nellie Tayloe Ross. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2005.

- “Mrs. Ferguson files for governor.” Bryan (TX) Eagle, 29 May 1924.

- “Ferguson barred from ballot, will campaign for wife.” Austin Statesmman, 8 Jun 1924.

- “Farmer Jim’s wife in race for governor.” Austin Statesman, 10 Jun 1924.

- “Woman opens her campaign for governor.” Shreveport (LA) Times, 18 Jun 1924.

- “Mrs. Ferguson’s plea for votes is unique.” Houston Post, 22 Jun 1924.

- “Mrs. Ferguson now nursing handshaked right arm and hand.” Bryan (TX) Eagle, 19 Jul 1924.

- “Stop waste, cut expense plan of all.” Fort Worth Record-Telegraph, 20 Jul 1924.

- “Mrs. Ferguson is running close contest with Whit Davidson for third place.” Fort Worth Record-Telegraph, 27 Jul 1924.

- “Mrs. Ferguson reverses Farmer Jim on education.” Austin American, 1 Aug 1904.

- “‘Ma,’, back home, says ‘I’ll miss my kitchen.'” Fort Worth Record-Telegraph, 23 Aug 1924.

- Clark, J. Mabel. “‘Ma’ considers bobbed hair and fox trotting.” Fort Worth Record-Telegraph, 25 Aug 1924.

- “‘Ma’ Ferguson: ‘Why I fought Klan.'” Fort Worth Record-Telegraph, 31 Aug 1924.

- Ferguson, Miriam. “Common people will rule at Austin, ‘Ma’ declares.” Fort Worth Record-Telegraph, 1 Sept 1904.

- “Ferguson forces have control.” Galveston Daily News, 2 Sep 1924.

- “Platform banishes mask.” Austin American, 3 Sep 1924.

- “‘Ma’ Ferguson enjoys rocking chair vacation.” Houston Post, 7 Sep 1924.

- “Ma’s peach preserving is done and issue is closed.” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 10 Sep 1924.

- “Latest injunction causing no worry for the Fergusons.” Austin Statesman, 11 Sep 1924.

- “Legal tangle being woven to bar ‘Ma.'” Austin American, 14 Sep 1924.

- “Conspiracy charged by Ferguson.” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, 22 Sep 1924.

- “Attack on women’s rights.” Austin Statesman, 23 Sep 1924.

- “‘Ma’ Ferguson wins — injunction brought by Dickson is refused.” Bryan (TX) Daily Eagle, 29 Sep 1924.

- “The dramatic story of Texas’ ‘Ma’ Ferguson.” Austin Statesman, 5 Oct 1924.

- “Widow of governor to ‘carry on;’ asks ban on sentiment.” Los Angeles Evening Express, 15 Oct 1924.

- “Boosting Mrs. Ross.” Edwardsville (IL) Intelligencer, 15 Oct 1924.

- “Ma wins in court and Jim gets busy.” Austin American, 19 Oct 1924.

- “Women candidate marvel in science.” Washington (DC) Evening Star, 26 Oct 1924.

- “Warren, Winter and Mrs. Ross win state.” Casper (WY) Star-Tribune, 5 Nov 1924.

- “Sullivan pledges help to Mrs. Ross.” Casper (WY) Star-Tribune, 7 Nov 1924.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: