The First Battle of the American Revolution

why it's not the Battle of Point Pleasant

The Battle of Point Pleasant

It was 1774, and all was not quiet along the frontier.

Pennsylvania and Virginia had been fighting over the territory west of the Appalachians for a decade. Virginia seemed to have won the war when Governor-in-Chief John Murray, the Fourth Earl of Dunmore, marched a column of militiamen up to Pittsburgh and seized Fort Pitt, but the conflict still threatened to reignite at any moment.

The Shawnee had been forcibly relocated to the area when the Iroquois sold their lands to the Penn family, and once again white men were encroaching on their area. Chief Hokoleskwa, known to the English as “Cornstalk,” saw the chaos in Pittsburgh as an opportunity to claw back some of their power. He mounted a series of raids against frontier settlements and attempted to unite other nations into an anti-British coalition. The Virginia and Pennsylvania legislatures were slow to respond to the Shawnee threat, so locals took matters into their own hands.

In the Spring of 1774 William Cresap assembled an illegal militia to deliver some frontier justice, which is to say, indiscriminately kill Native Americans. On April 30 a detachment of Cresap’s militia led by Daniel Greathouse shot two Mingoes who were trying to steal horses, then proceeded to a tavern at Baker’s Bottom along Yellow Creek. A second group of drunk and unarmed Mingoes, who had no idea what was going on, mocked the militiamen. One even stole a coat and ran around laughing, “I am a white man!” In response the militiamen opened fire, killing five men and two women. A third group of Mingoes came to investigate the noise, startled the militamen as they were scalping their victims, and were also killed. In total, some twelve Mingoes were murdered by Greathouse and his men over the course of the day.

Native Americans were outraged by the massacre, and none more than the Mingo Chief Talgayeta, known to the English as “James Logan”: the victims included his brother Taylayne, his nephew Molnah, and his wife Koonay. His two-month-old daughter was the only survivor of the slaughter. Up to this point Logan had been known for his generous heart, his desire for peace, and his boundless love for his fellow man. Now something snapped inside and his heart burned only with vengeance. He led a series of savage attacks on settlements from the confluence of the Ohio all the way down to Grave Creek.

The call to arms was sounded. The first eight hundred militiamen who answered were put under the command of Colonel Andrew Lewis and sent off to the confluence of the Kanawha and the Ohio to begin building fortifications that could be used as a rallying point for future operations. Dunmore remained at Fort Pitt until he had raised another 1700 militiamen, then marched them down the Ohio to join Lewis.

Lewis and his men managed to make it through the Kanawha Valley unmolested, mostly because the Natives weren’t stupid enough to directly engage hundreds of angry white men with guns when it was easy enough to slip around them and raid behind them. On October 6 they arrived at their destination, a swampy little spit of land between the two rivers known to the Natives as “Tu-Endie-Wei” (“the place between two waters”) and to the British as “Point Pleasant.”

Cornstalk and Logan could see where this was all heading, and they didn’t like it. It was bad enough that Virginians were building fortifications deep inside their territory, but if Lewis and Dunmore joined forces they would outnumber their braves 3:1 and there wasn’t much clever tactics could do to close that gap. They needed to strike, and they needed to strike fast.

In the pre-dawn hours of October 10, 1774 some five hundred Shawnee braves took up position, stripped down to their battle dress, and began silently stalking through the woods. Before they reached their target they bumped into a hunting party leaving camp. A skirmish broke out and most of the hunters were killed, but two managed to scramble back behind the palisade and raise the alarm.

Lewis quickly dispatched two columns of men, one along the Ohio and the other along the Kanawha, with orders to re-form behind the Shawnee. He was trying to trap the Natives between the unified column and the camp, so they would be annihilated.

Cornstalk saw right through that plan and called an audible, in an attempt to stop those two columns from uniting at any cost. The place between two waters became a scene of pure chaos. A constant stream of wounded militiamen staggered back to camp for medical care, and fresh troops were sent out to replace them. Officers dropped like flies, including Lewis, who was shot early and conducted most of the battle from a stretcher.

Eventually the two columns of militiamen managed to form a continuous line of battle and transform the engagement into a turkey shoot. It didn’t take long for Cornstalk to realize that the jig was up. He began pulling his forces back at noon, though there were scattered engagements right up until dusk. The arrival of Virginian reinforcements shortly after nightfall finally brought a conclusive end to the battle.

When the dust cleared the Virginians counted 75 dead and 140 wounded, a horrifying casualty rate of about 20%. The Shawnee had only lost forty braves, but their failure to dislodge the Virginians meant they had lost the war. When Lord Dunmore and his men finally arrived on the scene a few days later they decided to sue for peace. In the Treaty of Camp Charlotte they relinquished their claims to all land south of the Ohio River.

These days few people remember Lord Dunmore’s War and the Battle of Point Pleasant, but at the time they were a big deal, hard-fought victories won by brave frontiersmen which secured the border and made Native Americans hesitant to ally with the British during early months of the American Revolutionary War.

To the residents of Point Pleasant the battle was the most important thing that had ever happened in their fair city, so naturally they wanted to commemorate it. In 1848 they proposed erecting a monument to the battle in honor of its diamond anniversary, but the Virginia state legislature wasn’t interested. The legislature was more receptive in 1860, but then got distracted by the Civil War. The idea was revived a decade later in 1873, and while the West Virginia legislature acted too slowly to have anything ready for the battle’s centennial they set aside some funds in the hopes that they might get something ready for the national Centennial in 1876, and then never disbursed those funds.

The project only got off the ground in the 1890s thanks to the tireless efforts of Livia Nye Simpson Poffenbarger, a Point Pleasant society matron and head of the local chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. She spent more than a decade campaigning, writing editorials, giving speeches, and hectoring legislators before her efforts finally bore fruit.

In 1901 the state purchased the battlefield; in 1902 it set it aside as Tu-Endie-Wei State Park; in 1908 it raised funds for a memorial; and in 1910 a tasteful obelisk was dedicated on the anniversary of the battle.

I visited Tu-Endie-Wei during a 2022 road trip through West Virginia, because of course I did.

If you start at the Mothman statue — and let’s be blunt, the only reason you’d be visiting to Point Pleasant is to see the Mothman statue — just walk in the direction he’s facing and you’ll pass through a gate in the flood wall into the state park. Enjoy a leisurely walk south along the wall, which is decorated with a panoramic mural of the battle and several nifty statues depicting its most notable participants. After a few minutes you’ll reach the heart of the park, a small garden square built around the obelisk.

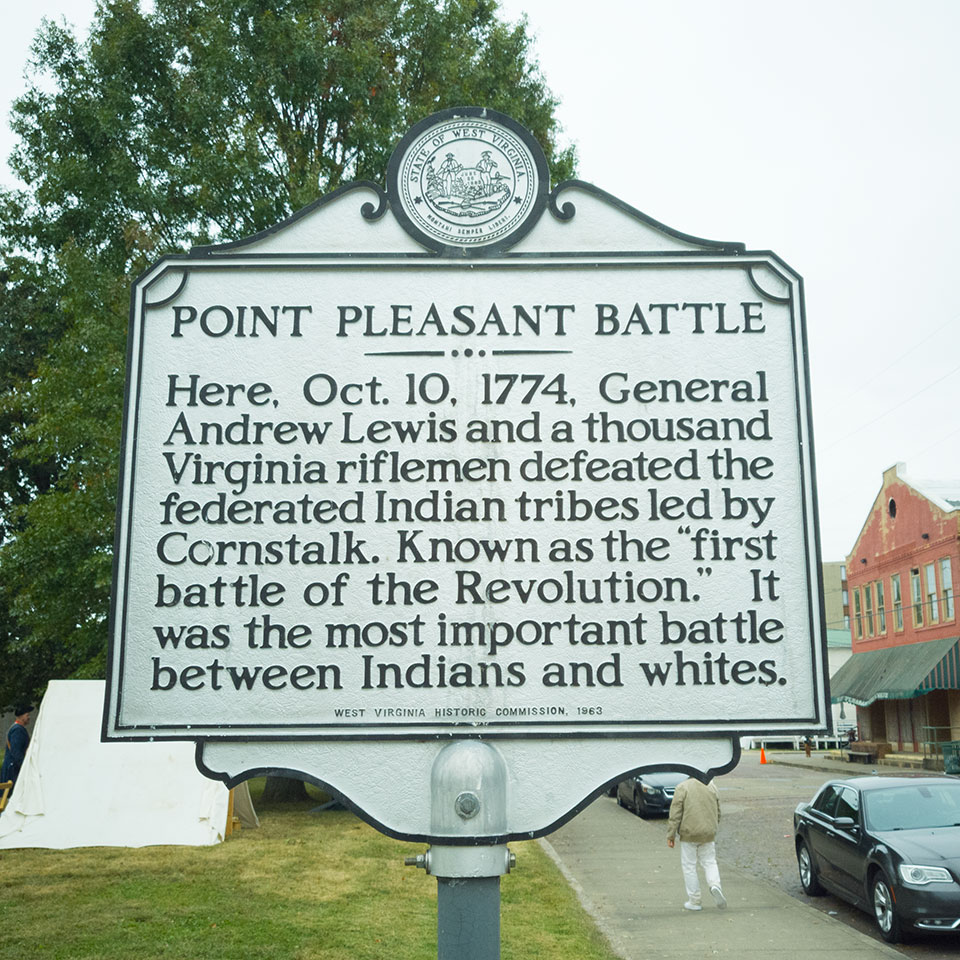

It’s a somber and affecting memorial, though the plaque describing the battle as “the most important battle ever waged between the forces of civilization and of barbarism in America” could probably stand to be replaced with something a little more woke. On the other hand, as I walked down Main Street to get back to my car, I couldn’t help but notice the historical marker right by the park entrance…

Point Pleasant Battle: Here, Oct. 10, 1774, General Andrew Lewis and a thousand Virginia riflemen defeated the federated Indian tribes led by Cornstalk. Known as “the first battle of the Revolution.” It was the most important battle between Indians and whites.

[record scratch] What?

The First Battle of the American Revolution

Before we begin let me reassure you that for once everything you learned in school was actually correct. The first battles of the Revolutionary War are Lexington and Concord and nothing can change that. The real question here is not, “What is the first battle of the American Revolution?” but “Why is West Virginia’s answer to that question different from everyone else’s?”

Surprisingly, the idea has old roots.

Virginians believed that thr war was necessary but weren’t terribly enthusiastic about it. Indeed, the House of Burgesses only begrudgingly permitted Lord Dunmore to raise a militia and never actually allocated any of the colony’s resources for the war, forcing Lord Dunmore to pay for everything out of his own pocket.

Pennsylvanians never trusted Dunmore, and believed he was deliberately overhyping the threat of the Shawnee so he could use the militia to steal Westmoreland County from them. They used Dunmore’s own actions as evidence:

- His initial attempts at diplomacy were curiously hostile, demanding that the Shawnee unconditionally surrender or he would “proceed against them with Vigour & will show them no Mercy.”

- When war became inevitable he actively recruited known troublemakers like William Cresap, Daniel Greathouse, and Simon Girty.

- He deliberately sent Colonel Lewis into the heart of enemy territory, confused him with a series of poorly-worded orders, and was slow to provide reinforcements.

- When the Shawnee finally sued for peace he was in no hurry to respond.

From there it was only a hop, a skip, and a jump to the idea that Dunmore’s actions were deliberate provocations intended to make the situation along the frontier worse.

Then the Revolution broke out. Lord Dunmore went from frontier hero to disgraced exile overnight. Even Virginians found fault with how Dunmore had prosecuted the campaign, with notables like Charles Lee calling it “an impious, black piece of work…”

Everyday Americans found themselves fighting opposite the very men who had been their allies only six months earlier. Some of them could not handle the cognitive dissonance. They began wondering if Lord Dunmore’s War was a secret plot to weaken America in the months before the Revolution. Had he made a secret alliance with the Shawnee, arming them and allowing them to freely raid the frontier? Had he deliberately hung Colonel Lewis and his men out to dry? Could it be that the only thing that foiled his dastardly plan was that Virginians were too tough and brave to be laid low by mere treachery?

It’s worth pointing out there’s no documentary evidence whatsoever for this hypothesis. The diaries and correspondence of everyone involved, from Lord Dunmore down to the lowliest soldier, indicates that their motives were obvious and straightforward: they were trying to secure the border against the threat of hostile Native Americans. Documentary evidence isn’t the only sort of evidence… But in this case it is really quite damning that there’s none whatsoever in favor of the stab-in-the-back theory.

Once you’ve become paranoid enough to contemplate it, though, it’s only a short leap to the idea that the Battle of Point Pleasant was secretly the first battle of the American Revolution.

Except no one made that jump until the arrival of Livia Nye Simpson Poffenbarger on the scene.

So where did Poffenbarger get the idea from? Here are her own words, from the speech she gave at the dedication of Tu-Endie-Wei State Park…

I wish to impress upon all here to-day is the fact that ours is the only society professing to be founded exclusively upon our Revolutionary struggle that recognizes the Battle of Point Pleasant as a part of the war for American independence. Reputable historians, including [George] Bancroft, President Roosevelt and others, have asserted that it was the initial, the first battle of the Revolutionary War. Moreover, they have produced the indisputable evidence upon which the assertion is based. What the consensus of American opinion will be as the years shall roll on and historical research shall bring to light the whole truth, we cannot say. If the verdict shall be the affirmative of that proposition then the first battle will not be lacking in display of heroism and patriotism, exhibited in the midst of an almost interminable wilderness and hand to hand with a savage and at the same time valorous foe.

Reputable historians, eh?

George Bancroft’s History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent makes no reference to the stab-in-the-back theory, nor does it make any attempt to connect Lord Dunmore’s War to the American Revolution.

Theodore Roosevelt’s The Winning of the West mentions the stab-in-the-back theory and explicitly rejects it, but also contains the following passage:

Lord Dunmore’s War, waged by Americans for the good of America, was the opening act in the drama whereof the closing scene was played at Yorktown. It made possible the twofold character of the Revolutionary War, wherein on the one hand the Americans won by conquest and colonization new lands for their children, and on the other wrought out their national independence of the British King… Had it not been for Lord Dunmore’s war… it is more than likely that when the colonies achieved their freedom they would have found their western boundary fixed at the Alleghany [sic] Mountains.

“The opening act in the drama whereof the closing scene was played at Yorktown” sure makes it sound like Roosevelt is on Poffenbarger’s side… but go back and listen to that passage again. The important phrase is “waged by Americans for the good of America.” Roosevelt is saying that Lord Dunmore’s War enabled America’s territorial expansion, and is of a similar character to the Revolution… but he does not say it is a part of it.

And why would he? Lord Dunmore’s War was a war of security and territorial expansion. The American Revolution was about independence and liberty (and maybe also about not paying taxes). They are very different conflicts fought for very different reasons.

If Poffenbarger got her ideas from Bancroft and Roosevelt, it was only because she was doing a lot of reading in between the lines. Why would she do that? The answer seems to be pride. She saw other cities and states celebrating the glories of their past and wanted to do the same thing in Point Pleasant… and maybe, just maybe, attach her name to a big public project that would cement her legacy forever.

The problem was that Point Pleasant only had one historical event worth celebrating and it was hard to gin up enthusiasm for it because it was obscure and overshadowed by contemporary events. Who would ever get excited about the anniversary of Lord Dunmore’s War when the anniversary of the American Revolution was only a few months later?

But what she could make Lord Dunmore’s War part of the American Revolution?

It was a ridiculous idea, but if anyone could make it work it was Livia Nye Simpson Poffenbarger. Earlier I called her society matron, which is true… but she was also a millionaire, publisher of the largest newspaper in West Virginia, and wife of a state Supreme Court justice. She could use her political capital to sway legislators in Charleston, her social capital to convince the fellow matrons of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the bully pulpit of the State Gazette to persuade the common man.

Her campaign started in 1888, when her pet legislators began introducing resolutions declaring the Battle of Point Pleasant a battle of the American Revolution. Others scoffed, calling it a “novel argument” but rejecting it.

A decade of constant repetition eventually cemented the idea in the public’s mind. Well, at least in West Virginia. No one outside of the state seemed to have any idea that history books were being rewritten.

There was some opposition. West Virginia State Historian Virgil A. Lewis politely pushed back whenever he could. He was always ready to rebut Poffenbarger’s assertions with logically sound articles, books, and speeches carefully explaining why she was full of shinola.

His primary arguments were:

- Lord Dunmore’s motives were well-attested to and not sinister.

- Dunmore was actually well-liked at the time of the war. No one suggested he was up to no good until after the Revolution, when he had become a reviled figure.

- The strange and inconsistent actions which made Dunmore seem to be a schemer were just coincidences created by incompetence, the vastness of the wilderness, and the fog of war working together.

- Contemporary historians considered Dunmore’s War a “colonial conflict” and part of the Revolution. Colonel John Stuart even wrote, “it could not be [sic] hardly be considered as connected with the Revolution, and that because of this, neither the heirs of General Lewis nor those of any of his officers, ever made claims for services in lands or otherwise.”

- Elaborating on Stuart’s point, veterans of the Battle of Point Pleasant were not awarded pensions by Congress for their military service. Indeed, at least one such veteran, Joseph Mayse, actively sought a pension and was explicitly denied.

Therefore, said Lewis, the Battle of Point Pleasant was emphatically not a battle of the Revolution.

I’ll add one more item to the list — if we are opening up the definition of the American Revolution to include other conflicts, why are we stopping in 1774? Why not include the War of the Regulation, an actual attempt to overthrow the colonial government of North Carolina that lasted from 1766 to 1771? That has the advantage of actually being about independence, but you never hear anyone saying that the Battle of the Allamance was the first battle of the American Revolution.

In the short term, though, Poffenbarger won the day. In 1908 the United States Congress passed a resolution that explicitly called the Battle of Point Pleasant a battle of the Revolution. (Of course, it’s easy to get legislators to do something stupid — remember that in 1971 the Texas legislature passed a resolution honoring Albert Di Salvo for his work in population control.) And of course she eventually got her monument. During her victory lap she even threw in a few digs at Lewis, most notably failing to invite him to the dedication and instead inviting Virginia State Historian Annie S. Green.

In the long term Lewis won, because let’s face it, had you heard of the Battle of Point Pleasant being the first battle of the American Revolution before today? No one outside of the state has ever considered the idea. Residents of West Virginia aren’t taught about it in schools. Even the West Virginia Departments of Tourism and Natural Resources don’t endorse the idea — the state parks website mentions the controversy but declines to pick a side.

In spite of massive public indifference the idea still resurfaces every few decades when it is politically and financially convenient. The idea seems to be about turning the battlefield into a site for historical tourism, to help juice Point Pleasant’s economy and offset the decline of the Rust Belt.

It was resurrected in the 1970s when the state wanted to get a piece of that sweet, sweet Bicentennial money. Governor Arch A. Moore Jr. issued a proclamation reaffirming that the Battle of Point Pleasant was a Battle of the American Revolution, but the Daughters of the American Revolution and the American Revolution Bicentennial Commission explicitly rejected the idea.

In the 1990s Point Pleasant tried once again, trying to replicate the success of Harper’s Ferry, which had rejuvenated its moribund economy by catering to Civil War tourists. Once again the idea was rejected; the National Park service was being starved for funds and Federalizing land (even small battlefields) had become a controversial issue in some circles.

Point Pleasant eventually found some economic success in the early 2000s by embracing the only other interesting thing that had ever happened there: the mysterious visits of Mothman, the cuddly psychic cryptid who just wants to warn you about your impending doom.

The irony is that Mothman is just as fictional as the town’s other claim to fame. I take some consolation, though, from the fact that Mothman is a myth that can be indulged in for fun without having to rewrite history in the process.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

William Cresap’s father Thomas was the primary instigator of a boundary war between Pennsylvania and Maryland (“The War Between the States”).

Chief Logan attacked settlements from Pittsburgh down to Grave Creek. Grave Creek runs through Moundsville, West Virginia, whose most notable feature is a large burial mound from the Adena culture. In 1838 fortune hunters dug up a rune-carved stone in the mound, which they claimed was evidence of a pre-Native American moundbuilder civilization, possibly Viking in origin (“Westward Huss”).

The “White Savage” Simon Girty served in Dunmore’s army during the war (“He Whooped to See Them Burn”).

These days Point Pleasant is best known as the home of Mothman, but if you ask me Mothman sucks. I’d rather spend my time hunting for West Virginia’s second most famous cryptid: Braxxie, the Flatwoods Monster (“Worse Than Frankenstein”).

Sources

- Bancroft, George. The History of the United States from the Discovery of the American Continent, Volume 7. Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1875.

- Downes, Randolph C. “Dunmore’s War: An Interpretation.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review: Volume 21, Number 3 (December 1934).

- Kruse, Robert J. II. “Point Pleasant, West Virginia: Making a Tourism Landscape in an Appalachian Town.” Southeastern Geographer, Volume 55, Number 3 (Fall 2015).

- Lewis, Virgil. History of the Battle of Point Pleasant Fought Between White Men and Indians at the Mouth of the Great Kanawha River (Now Point Plesant, West Virginia) Monday, October 10, 1774. Charleston, WV: Tribune Printing Company, 1909.

- McAllister, J.T. “The Battle of Point Pleasant.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 9, Number 4 (April 1902).

- McAllister, J.T. “The Battle of Point Pleasant (Continued).” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Volume 10, Number 1 (July 1902).

- Roosevelt, Theodore. The Winning of the West, Volume 1. New York: Review of Reviews Company, 1904.

- Sadler, Sarah. “Prelude to the American Revolution? The War of Regulation: A Revolutionary Reaction for Reform.” The History Teacher, Volume 46, Number 1 (November 2012).

- Simpson-Poffenbarger, Livia Nye. The Battle of Point Pleasant: A Battle of the Revolution, October 10, 1774. Point Pleasant: State Gazette, 1909.

- Williams. Glen F. Dunmore’s War: The Last Conflict of America’s Colonial Era. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2017.

- Wetzel, C. Robert. “The First and Last Battles of the American Revolutionary War: A Cautionary Family Quest.” Sons of the American Revolution. https://www.sar.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/The-First-and-Last-Battles-of-the-American-Revolution-by-C-Robert-Wetzel.pdf Accessed 2/24/2023.

- “Manufactured History: Re-Fighting the Battle of Point Pleasant.” West Virginia History, Volume 56 (1997).

- “Tu-Endie-Wei State Park.” West Virginia State Parks. https://wvstateparks.com/park/tu-endie-wei-state-park/ Accessed 2/23/2023.

- “A glorious day.” Weekly Register, 15 Oct 1874.

- “Monument at Point Pleasant.” Weekly Register, 17 Feb 1876.

- “The legislative.” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, 20 Jan 1887.

- “Charleston letter.” Weekly Register, 2 Feb 1887.

- Weekly Register, 12 Oct 1887.

- “Senator Faulkner to accompany the president.” Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, 20 Feb 1888.

- “Did Point Pleasant start the Revolutionary War?” Virginia Free Press, 26 Apr 1888.

- “West Virginia items.” Shepherdstown Register, 4 Jan 1889.

- “Point Pleasant.” Weekly Register, 4 Apr 1894.

- “A monument to commemmorate the Battle of Point Pleasant.” Weekly Register, 25 Sep 1895.

- “West Virginia pioneers.” Daily Register, 8 Apr 1896.

- “The celebration of the one hundred and twenty-seventh anniversary of the Battle of Point Pleasant.” Weekly Register, 16 Oct 1901.

- “Big column to be erected here this summer.” Point Pleasant Register, 28 Apr 1909.

- “Dedication October 10.” Independent-Herald, 29 Apr 1909.

- “A Virginia monument.” Point Pleasant Register, 16 Jun 1909.

- “West Virginia homecoming week.” Point Pleasant Register, 16 Jun 1909.

- “The Battle of Pt. Pleasant.” Independent-Herald, 2 Sep 1909.

- “Battle of Point Pleasant.” Point Pleasant Register, 29 Sep 1909.

- “Proudest day in West Virginia.” Point Pleasant Register, 13 Oct 1909.

- “Politicians led by woman.” Kansas City Star, 2 Oct 1910.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: