The Number of the Stars

are there really twelve planets?

If you are a long-time listener to this show you may remember the following passage from episode #55, “Lost Legacy,” about the so-called Mitchell-Hedges Skull of Doom…

An elaborate mythology began to develop around the idea that there were other crystal skulls, like the one in the British Museum… each set of skulls consisted of twelve skulls representing the twelve planets, which stored the minds and knowledge of ancient Atlantean aliens or something…

Was that really three years ago now? How time flies.

In that clip I offhandedly mention that there are twelve crystal skulls, one for each of the twelve planets. At the time you might have heard that and gone, wait, twelve planets? Where did that number come from? And honestly I was confused too, but the number wasn’t important to the story I was telling at the time and I just moved on.

The question never really went away, though. Where did this extraordinary claim that there are twelve planets come from?

Most articles about the Skull of Doom attribute the claim to Native American legends, without specifying specific legends or tribes. I’ve listed to enough episodes of Tales from Aztlantis to know that’s code for “I don’t know and I can’t be bothered to check.”

Other sources attribute the claim to the Maya, and then go on to explain how the Maya learned about the extra planets from the Atlanteans in the days after the Great Deluge. As you can imagine, I couldn’t take those sources seriously at all.

It looked like if I wanted to get to the bottom of this, I would have to have to do some digging.

Not that much digging. If you Google “twelve planets”…

Well, actually, the first thing that comes up is a bunch of Battlestar Galactica wikis, but once you filter out the phrase “Lords of Kobol”…

Well, you get a lot of angry forum posts from the time they demoted Pluto to dwarf planet, but once you filter out that…

You get Zecharia Sitchin.

Sitchin was a self-taught linguist who claimed his idiosyncratic translations of cuneiform writings revealed that the Sumerians gods were ancient astronauts who genetically engineered our ancestors to be slaves. More importantly, Sitchin also claimed that the gods bestowed their advanced knowledge on these early humans, including the fact that there were twelve planets. That includes the Sun and Moon and also the mysterious planet Nibiru from whence the gods came.

That sounded like the beginning of an episode to me. All I had to do was read half a dozen or so books by a well-known pseudo-scientific crank, chase them with several dozen articles by skeptics debunking him, and find some way to present that information in an entertaining fashion.

Easy peasy.

As I researched that episode I realized that something just didn’t feel right. The 12th Planet, the first book in Sitchin’s “Earth Chronicles” series, was published in 1976. But I knew I’d seen references to “the twelve planets” that predated it.

I went digging through my research notes on “Seven Minutes in Heaven,” about William Dudley Pelley, and was reminded of his associate George Hunt Williamson, whose “Knights of the Solar Cross” were sworn to defend the twelve planets. Williamson’s books were published in the late 1950s.

A decade earlier, UFO contactee George Adamski casually mentioned the twelve planets but did not provide any more detail.

I was also pretty sure I remembered a references to twelve planets in old Theosophy texts, or maybe in the Oahspe. I wasn’t going to go check, though, because you can’t possibly pay me enough money to read that gibberish again.

My suspicions had been confirmed, though. The idea that there were twelve planets predated Sitchin by at least two decades, if not by an entire century. If the number didn’t come from him, where did it come from?

It turns out the answer was pretty simple, though it took me a while to find it.

What Is A Planet, Exactly?

Let’s establish what a planet is.

The International Astronomical Union defines a planet as a celestial body which directly orbits a star, with sufficient mass to collapse into a roughly spheroidal shape, and which has managed to clear its orbit of any other celestial bodies or capture them as moons.

Of course, that is the modern definition, built on thousands of years of scientific progress. The earliest astronomers had a very different and much simpler idea of what a planet was.

When humanity first looked up at the heavens it noticed a few things. There were the Sun and Moon, which are pretty hard to miss. Then there were the stars. And then five things that at first seemed to be stars — but while the stars moved through the night sky in a nice orderly progression, these weirdos had odd paths that arced, looped, and occasionally doubled back on themselves or spiraled.

Everyone noticed these star-like things, but it was the Greeks who called them planetes, or wanderers. The Romans gave them the individual names we know them by today: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.

No one was quite sure what they were. Aristarchus of Samos thought they were stars that were much closer to the Earth. He assumed that the other stars had orbits every bit as janky, which only seemed more regular because they were so far away. That’s a pretty good hypothesis, even if it is wrong.

At least Aristarchus had a hypothesis. Everyone else just shrugged their shoulders and treated the planets as five weird anomalies.

Now five, of course, is not twelve. So who was saying there were twelve planets? And what were those extra seven planets?

- Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto wouldn’t have been on the list. They’re not visible to the naked eye and the naked eye was all the Ancients had.

- The Sun and the Moon wouldn’t have been on the list, either. They were so much larger than everything else in the sky they were put in their own separate categories.

- Earth definitely wouldn’t have been on the list. Most cultures still thought it was at the center of the universe because they lacked the paradigm to understand that it was just another planet.

I pored through countless books on astronomy. No one (and I mean no one) ever claimed that there were twelve planets. The closest I could get was Philolaus of Croton, who believed that there were ten objects orbiting the “central fire” of the universe — the Sun, the Moon, the Earth, a “Counter-Earth” in our orbit but on the opposite side of the Sun, the five planets, and a crystal sphere that the stars were mounted on. That’s only ten objects, mind you, and still only five planets.

I was told that the Qu’ran said there were twelve planets, but when I tracked down the surah in question I was once again disappointed…

˹Remember˺ when Joseph said to his father, “O my dear father! Indeed I dreamt of eleven stars, and the Sun, and the Moon — I saw them prostrating to me!”

Surah Yusuf, 12:4

That’s eleven, not twelve, and stars, not planets.

I thought maybe the number twelve had some numerological significance. Except in most numerological systems two digit numbers get reduced to single digit numbers. Twelve, in particular, reduces to 1+2=3, and we all know that three is a magic number somewhere in the ancient mystic trinity; the past, the present, and the future; faith and hope and charity; the heart, the brain, and the body… but no one’s claimed there were only three planets either.

Maybe twelve was just a symbolically powerful number? There’s no denying that we love to group things in dozens. Since the days of Babylon there have been twelve months and twelve signs of the Zodiac. The Greeks had twelve virtues; twelve Olympian gods; and twelve Labors of Hercules. In the Torah there are twelve patriarchs; twelve sons of Jacob who sire the twelve tribes of Israel; twelve lesser prophets. In the New Testament you have twelve Apostles; and twelve gates, angels, legions of angels, and foundations in the Book of Revelation. If you want to dip into the woo-woo a bit, there are also twelve Laws of Atlantis and the twelve Emerald Tablets of Hermes Trismegistus.

Except while everything else seemed to be cheaper by the dozen, the planets remained a stubborn exception.

I thought maybe there’d be some philosophical system where there would be one planet for each Olympian god. Nope!

One source that said there was a list of twelve gemstones that were associated with the twelve planets. Upon further examination it was just a list of the birthstones and “planets” was either a poetic or sloppy translation for “Zodiac signs.”

That also turned out to be the case when I found a list claiming to show how the twelve Apostles mapped on to the twelve planets. Planets once again meant Zodiac signs.

That got me thinking. Maybe I was looking in the wrong place.

Astrology

Maybe the answer didn’t lie in astronomy, but astrology.

What do you know, as soon as I started looking into astrology I found the answer almost immediately.

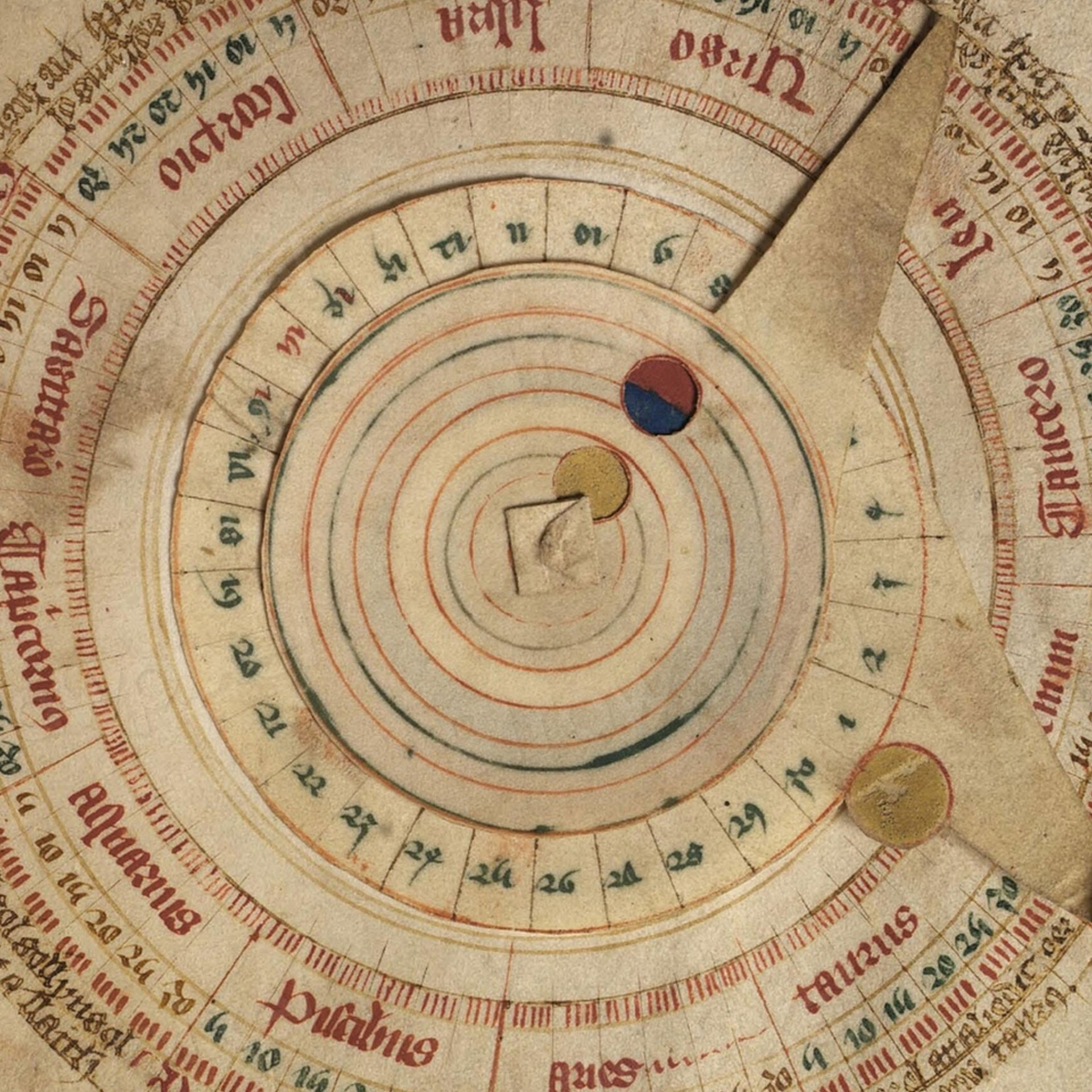

Back in the time of Babylonia some astrologer decided that each sign of the Zodiac was “ruled over” by one of the planets. There was the slight problem that there were twelve signs of the Zodiac and five planets, but our astrologer was clever. He decided to have all the planets pull double shifts.

Take a look at any chart showing the classical “Chaldean Zodiac.” You will notice that, when it comes to planets, one side of the chart is a mirror image of the other half. Mercury rules both Gemini and Virgo, Venus rules both Taurus and Libra, and so on. The Sun and Moon fill the remaining two slots, with the Moon ruling Cancer and the Sun ruling Leo.

That’s how we get to twelve planets.

Except though there are actually only seven “sacred planets” or “mystery planets”. And only five of them are actual planets.

It’s messy, but if you’re results-focused it works. As much as anything in astrology can be said to work.

The idea that the stars and planets influence our lives has always been a pretty dodgy proposition at best. Yes, the force of gravity is infinite in its reach, but the idea that distant celestial bodies can influence the day-to-day minutiae of our life is pretty silly. Might they have some nearly insignificant effect on the weather? Sure. Are they going to make me meet a tall dark handsome stranger? No.

I saw through it at a pretty early age, though it helps that in elementary school I knew a boy who was born the same day and hour as I was, in the same hospital, who even had the same first name. According to astrology our lives should be very similar, but they couldn’t be more different. He’s a writer and a professor, and I build websites and do whatever this is for fun at night.

(On the off chance that David Amadio is out there listening to this: Hi! It’s Dave White from Ardmore Avenue Elementary. I read your book. It’s really good.)

Eventually there came a day when even astrologers had to admit how dicey the entire idea of planetary rulership was.

Specifically, that day was March 13, 1781 when William Herschel first laid his eyes on Uranus.

Got the giggles out of your system? Good.

For most people, the discovery of a new planet would be a thrilling scientific breakthrough. For astrologers it was an existential nightmare. Their entire pseudo-science was based on the idea that heavenly bodies influenced events on Earth. What did it mean that there was a new heavenly body they had never heard of? Was every prediction they had ever made wrong?

I mean, yes, of course every prediction they had ever made was wrong, but you know what I’m trying to say.

Astrologers were forced to adapt. Some abandoned the idea of planetary rulership entirely. Some kept on doing what they’d been doing, claiming that if Uranus was really all that important the Ancients would have known about it, or that it was too far away to affect things on Earth (which is hilarious because distant objects affecting things on Earth is the whole basis of astrology). Others tried to incorporate the new planet into the rulership system, even though that made the chart unpleasingly unbalanced.

Just when astrologers finally thought they had everything figured out and could get back to business, some schmuck went and discovered Ceres in 1801. And Neptune in 1846. And Pluto in 1930. And a whole ton of asteroids, dwarf planets, and more along the way.

Eventually modern astrologers found a way to work the Sun, the Moon, and the other planets into the rulership system (though they still have to double up Venus and Mercury to make the numbers work out right).

Everything was up in the air for a very long time, though. And in that time people came up with some really crazy ideas.

Theosophy

Some of the craziest came from our old pals the Theosophists.

You might think the Theosophists only recognized the seven “sacred planets” of traditional astrology, because they were obsessed with the number seven.

In Theosophy there are seven elements; Seven Eternities in the Septenary Hierarchies; Seven Ways to Bliss; Seven Truths; and Seven Keys to the Temples of Ancient Wisdom. There are Seven Sublime Lords; Seven Lords of Meditation; Seven Creative Spirits; Seven Sons of the Web of Life; and the Primordial Seven, who take Seven Strides through the Seven Regions Above and the Seven Regions Below. In the House of Seven Gables there are seven brides for seven brothers with seven sacks with seven kittens standing on the corner in Winslow, Arizona with seven women on their mind.

A casual glance through their writings would seem to confirm that hypothesis. But once you do some digging it falls apart.

One of the key ideas behind Theosophy is that it unifies pre-existing belief systems. That means retaining as many ideas from belief systems as possible regardless of whether they make sense when those belief systems get smushed together.

So Theosophists keep the astrological idea that there are twelve planets ruling the Zodiac but change them from planets to “planetary chains” or “planetary cycles.” Planetary chains typically include more than one planet but function similar to the ruling planets with a built-in fudge factor to help hand-wave away the ambiguities that arrive from incompatibilities in the merged doctrines.

From there it all gets a little hinky, because there are inevitably arguments about the best way to resolve those ambiguities. In practice that means no two Theosophists believe exactly the same thing. Eventually two major schools of Theosophical astrology developed, one championed by Theosophist-turned-astrologer Gottfried de Purucker, and another championed by astrologer-turned-Theosophist Alan Leo.

Let’s start with de Purucker, because his doctrine is more comprehensive and easier to understand.

…there are not only seven but twelve sacred planets, although, because of the extremely difficult teachings connected with the five highest, only seven were commonly mentioned in the literatures and symbols of antiquity. However, reference is made in places to twelve spiritual planetaries or rectors, which were known as the Twelve Counsel Gods and called in the Etrusco-Roman language Consentes Dii — ‘Consenting or Cooperating Gods.’ Thus it is that each one of the twelve globes of our earth chain has as its overseeing ‘parent’ one of these twelve planetary rectors. This shows clearly enough that the ancients, at least the initiates among them, knew of more planets in our solar system than the seven or five commonly spoken of.

First, we have the seven sacred planets of the Ancients. That includes Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. Though the Ancients included the Sun and Moon in that list, de Purucker does not. Instead, he says the Sun and Moon are mere stand-ins for planets which have only partly manifested in our physical universe, and therefore can only be seen by people who have achieved a certain level of spiritual development.

(Theosophists loved doing this sort of thing to explain why their numbers didn’t add up. Remember earlier when I said they believed in seven elements? Well, those seven elements were the five elements of classical Chinese philosophy and two more that only exist spiritually. The same thing is happening here.)

The Sun, supposedly, is a stand-in for the planet Vulcan. This is a whole story by itself, and one which other podcasts have already covered in great detail, but Vulcan was a hypothetical planet proposed by Urbain le Verrier to explain several anomalies in the orbit of Mercury. It was purportedly spotted by other French astronomers in the 1850s and 1860s but not by anyone else, which de Purucker explains by stating Vulcan “became practically invisible to the physical eye during the Third Root Race, after the fall of man into physical generation”. The problem here is that de Purucker was writing in the early Twentieth Century, when science no longer believed in Vulcan because they had explained away most of the anomalies in Mercury’s orbit with accurate measurements, and then explained away the rest by applying the Theory of Relativity. His take appears to be deliberately contrarian.

The planet near the Moon, on the other hand, is identified as the Black Blood Moon Lilith, which shares the Moon’s orbit but revolves in the other direction. The two do not smash into each other because they are not in the same physical continuum. I’m not even going to open that can of worms.

Okay, that’s seven planets, albeit two of them of dubious existence. Where do the other five come from? You will be surprised to learn they do not include Uranus or Neptune or Pluto.

Uranus is a member of the universal solar system, but does not belong to our solar system, even though as a true planet it is closely linked with our Sun both in origin and destiny. The only sense in which Uranus can be considered as a member of our solar system is the purely astronomical one, in that Uranus is under our system’s influence so far as the revolutions of its physical globe around the sun are concerned.

Neptune, on the other hand, is not by right of origin in this solar manvantara a member either of our solar system or of the universal solar system. As I have explained in my Fundamentals, it is what is called a capture, which event changed in one sense the entire nature of the universal solar system, and will remain with us until the karmic time shall come for it to leave… Likewise, the planet Pluto is a capture.

So, Uranus and Neptune and Pluto are part of the solar system physically but not part of the solar system spiritually. Got it. So to take their place we add in four spiritual planets that have yet to manifest in our physical reality, which are imaginatively called A, B, X, and Y.

That gets us to eleven. To bring us an even dozen de Purucker adds the Sun, even though he just finished explaining that it was not one of the sacred planets. I guess it’s still pretty sacred, though.

The reasoning behind de Purucker’s astrology may be tortured, but at least it’s internally consistent. Alan Leo doesn’t even have that going for him.

In addition to “planetary chains” and “planetary cycles” (which are different things) there are also “planetary logi” which are a third, entirely different thing and Leo is never clear which one he is talking about at any given moment. He just says “planets” and hopes you can infer what he means from context. He is also inconsistent about how the planets fall into those classifications.

Leo believes that Uranus and Neptune are an actual part of the solar system. He believes in Vulcan and Lilith but does not believe in the other invisible planets. Sometimes the Sun is the Sun, and sometimes the Sun is Uranus. Sometimes the Moon is a stand-in for Lilith and sometimes it’s just the Moon.

It’s all very confusing and it hurts my head so maybe let’s move on.

UFOlogy

We’ve seen how the idea that there are twelve planets was established by astrology and then expanded on by Theosophy. Theosophy then became enormously popular and its ideas influenced other esoteric philosophers, writers, and thinkers. Eventually its ideas became so ubiquitous that their origins were forgotten and they became the structural foundations of modern New Age movements.

That means these ideas just pop up in the strangest places. For instance, you would not have expected the idea that there were twelve planets to pop up in the writings of more scientifically-minded UFO cultists.

But it did.

The first reference pops up in the writings of UFO contactee George Adamski. The book Inside the Space Ships is devoted to Adamski’s encounters with the Space Brothers, which includes being taken for a ride on one of their flying saucers. While on board he casually glances over at a monitor and sees a depiction of our solar system with twelve planets orbiting the sun. But that’s all there is to it. Adamski does not name the extra planets or elaborate on their significance. It’s just a random background detail.

Other early UFO enthusiasts did elaborate. Central to the Soulcraft-inspired cosmology of George Hunt Williamson are the Knights of the Solar Cross. They protect all of the other planets of the solar system including Vulcan, Mercury, Venus, Earth (“Saros, the sorrowful planet”), Mars (“Masar”), Jupiter, Saturn (“home of the Universal Tribunal”), Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, and unnamed intra-Vulcanian and trans-Plutonian worlds. These worlds are all supposedly inhabited, though Williamson does not explain how that’s possible on the gas giants or the planets with surface temperatures that could melt lead or the planets with atmospheres made of sulfuric acid. Oh, and there was also a thirteenth planet, Lucifer (“Maldek, the silver-tongued”) which got blowed up by mad scientists who peppered in God’s lo mein but that was okay because its destruction got the number of planets in the solar system down to a properly symbolic number: twelve planets that align with the twelve signs of the Zodiac and the “twelve lessons of the Creator.”

No, I don’t know why everything has to come in groups of twelve either. It’s like we’re stuck back in the Magnesium Atom Totality.

Sitchin

And that brings back us to where started.

At some point in the 1950s Zecharia Sitchin, a Russian-born, Palestinian-raised economist, became obsessed with the cuneiform script of ancient Sumeria. Sitchin taught himself how to read the language from textbooks and then sat down to translate every clay tablet he could find. In the course of this project he discovered hidden histories and cosmic secrets that had somehow been ignored by every other archaeologist, linguist, and historian in the world.

Here’s a quick summary.

At some point in the distant past an immense exoplanet entered our solar system and really messed it up. In the outer solar system its tremendous gravity yanked Uranus over onto its side; reversed the orbit of Neptune’s moon Triton; ripped away one of Saturn’s moons and flung it into the depths of space where it became Pluto.

As it passed into the inner solar system the exoplanet’s satellites struck the planet Tiamat and smashed it into pieces. Tiamat’s liquid water froze solid and formed comets. The rocky detritus became the asteroid belt between Jupiter and Mars. The two largest fragments settled into stable orbits and became the Earth and the Moon.

The exoplanet itself was drawn into an irregular 3,600 year orbit around the sun and became the planet Nibiru. Intelligent life evolved there and formed an advanced civilization with access to crazy sci-fi super-science.

Even super-geniuses can be super-doofuses, though, and the Niburuans “punched a hole in their atmosphere” which caused the planet to “lose its internal heat.” They discovered they could patch the damage by spritzing gold flakes into their atmosphere, but did not have enough gold to finish the job.

About half a million years ago they discovered that Earth was lousy with gold and sent some brave explorers to our planet to get it. These ancient astronauts were called the Anunnaki (“Those of Heaven who are on Earth”) and the Nefilim (“Those who were cast upon the Earth”). The Anunnaki first attempted to extract gold from seawater but when that didn’t, uh, pan out they had to start mining it the old fashioned way.

About 300,000 years ago the miners decided that manual labor was beneath them and went on strike. The bitter conflict was only resolved when scientists spliced Nibiruan genes into the native “apewomen” to create the first hominids. The Anunnaki enslaved these proto-humans and ruled over them as god-kings.

About 12,000 years ago a close pass by Nibiru pulled the Antarctic ice pack into the ocean, causing a massive sudden rise in sea levels that submerged all of the planet’s landmasses. The Anunnaki were surprisingly cool with that, because they thought it would kill all of their now-rebellious slaves while keeping their hands morally clean. Unfortunately for them rebels helped the humans ride out the deluge in vast submarine “arks.” When the waters receded the aliens and humans negotiated an uneasy truce.

About 3,200 years ago nuclear war broke out between various factions of the Anunnaki. The resulting devastation killed most of the Nibiriuans on the planet and caused the Bronze Age collapse.

The remaining ancient astronauts abandoned our planet around 2,600 years ago during Nibiru’s most recent visit.

If this all sounds a bit familiar it’s probably because you’ve been playing too much Assassin’s Creed. Or watching too much of the so-called History Channel.

Now, there are a lot of obvious problems with Sitchin’s story.

Sitchin was not a linguist or historian, and while undoubtedly very intelligent he was clearly in way over his head. Like a lot of autodidacts he tended to favor his own ideas even when they were quite obviously wrong. When he did rely on outside scholarship he rarely cited it correctly, constructing whole books out of paraphrases, misquotes, and misunderstandings. This was likely intentional — the ambiguity allowed him to escape criticism and contradiction when he was called on his bullshit.

Experts who can actually read ancient Sumerian say that his translations are idiosyncratic at best but usually just flat-out incorrect.

A massive terrestrial planet with a long-period irregular orbit should not exist according to our current understanding of orbital mechanics. Nibiru should have either been drawn into a closer orbit, or have enough momentum to escape into interstellar space.

If a planet with that sort of orbit did exist it would be a massive ball of ice for most of its year, except for the brief period where it was in the inner solar system. It is highly unlikely that life as we know it could evolve under those extreme conditions, much less billions of years before it did so on Earth.

It’s not clear why super-intelligent beings would try to extract gold from seawater. There is quite a bit of gold in the ocean, but it’s spread across the entire ocean, which is, y’know, huge. When they gave up panning for gold they decided to mine deposits in Africa, instead of looking for easier-to-get surface deposits in other parts of the planet.

Despite being super-advanced technologically the Niburuans appear to be like kindergartners socially and emotionally. One dynastic fight between two rulers apparently culminated in a playground fight where they took turns kicking each other in the sack and biting each other on the dick. Which then made it hard for them to have sex with their sisters later.

But look, I could go on about the stupidity of Sitchin’s oeuvre for hours. I don’t have to do that, though. The aforementioned Paranoid Strain did three whole episodes on this stuff last year. And then for good measure you can go over to Michael Heiser’s website SitchinIsWrong.com, which goes into even more detail. Go check them out, I’ll put links in the show notes.

Instead, let’s get back to our problem. Why does Sitchin think there are twelve planets, to the point where his breakthrough book actually bears the title, The 12th Planet?

Sitchin’s twelve planets are the Sun, Mercury, Venus, Earth, The Moon, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, and Nibiru. He cites his own translations of Sumerian texts as proof of this claim, along with a single depiction of the solar system on a cylinder seal in the Vorderasiatiche Museum in Berlin.

Let’s start with the cylinder seal because that’s the biggest part of his argument. It depicts a circle in a six-pointed star, surrounded by eleven dots of different shapes and sizes. Sitchin’s argument is that this is the Sun, and the dots accurately show the relative size of the planets and their orbits.

Unfortunately the Sun is pretty uniformly depicted in Sumerian art as a circle containing a four pointed star with wavy lines coming out of its vertices — and this isn’t it. It is clearly some sort of star, but it’s not clear what the eleven spheres around it are. They can’t show the relative size of the planets, because at any scale like that Pluto and Mercury would have to be almost invisible. And their orbits are just wrong. There are some convincing arguments that the symbol might represent a star cluster like the Pleiades, but we don’t know for sure.

The word Nibiru does appear in Sumerian texts, but does not refer to a trans-Plutonian planet. The literal translation of the word is “a place of crossing” and it is used in a couple of different contexts. Sometimes it seems to be a line in the heavens, some sort of useful demarcation like the ecliptic. Other times it seems to be a poetic alternate name for the planet Marduk, which we know as Jupiter.

Sumerian astrological and astronomical texts all uniformly agree that there are five planets, the same five planets everyone else knew about. There’s nothing that could be construed as a reference to Neptune, Uranus, or Pluto.

Then there’s other questions, like why the list contains Earth’s moon but none of the larger moons of other planets? There’s nothing particularly special about our moon. Why does the list include the Sun, which is definitely not a planet?

(The answer, by the way, appears to “to pad out the list for marketing purposes.” If you start writing about aliens from Planet X people know you’re a kook from the get-go, but if you say they’re from Planet XII they’re intrigued.)

In response to his critics Sitchin scrambled to find other artifacts and documents that he could use to back up his assertions. For example, he pointed to an ancient Egyptian “celestial map” depicting twelve barques, which he said represented the twelve planets. Only at least six of those barques appear to be the invention of his fevered mind. In a more egregious example, he seems to have just redrawn the cylinder seal and then attempted to pass the drawing off as a second artifact.

In spite of these serious criticisms and the weakness of Sitchin’s rebuttals, The 12th Planet became enormously popular, mostly because it’s the New Age equivalent of comfort food. It’s just remixing the cosmic catastrophism of Immanuel Velikovsky with the ancient astronauts of Erich von Daniken. That makes it unoriginal but also easy to grasp.

It also had the good fortune of coming out at a time when Velikovsky’s influence was on the wane and it was becoming increasingly obvious that von Daniken was a fraud. Essentially Sitchin functioned as sort of an escape hatch for kooks looking for ideas to latch on to that weren’t radically different from the ones they already believed.

As Sitchin’s works became part of the New Age canon they became the latest vector for the idea that there are twelve planets. The idea got a further signal boost in the early 2000s when the History Channel went all in on Ancient Astronauts and other kooks made Nibiru a central part of the 2012 Mayan Apocalypse conspiracy.

Could There Actually Be Twelve Planets?

Now, I’ve just spent quite a bit of time laying out why there are not twelve planets, that there is no historical basis for the idea that there are twelve planets, and why some people today think there are twelve planets in spite of all that.

So let’s ask one final question: could there actually be twelve planets?

This is essentially a two-part question.

The first part is, are there more planets out there? The answer is, “Probably not.” There are almost certainly more dwarf planets out there, but anything with enough mass to be considered a planet would have likely been spotted by now. While we can’t definitively rule out that there might be something big on the edge of the solar system, odds are anything that far out escaped into interstellar space billions of years ago. That shouldn’t stop astronomers from searching the night sky for Planet X or Nemesis or Nibiru or whatever they want to call it. It just means they should be realistic about their odds of actually finding anything sizable.

The second part is, is there some way to jigger the list of planets we do know about so that there are twelve planets? The answer is, “Sure.” The definition of a planet is a completely arbitrary one. We’ve already seen how it evolved over time from “those five weird stars” to “something in orbit around the sun” before eventually settling on the more technical definition that demoted Pluto to a dwarf planet. There’s nothing stopping us from redefining the word yet again.

If you drop the requirement for a planet to have cleared their orbit of debris, and replace the “mostly spherical” requirement with a radius or mass requirement, you can add Eris, Haumea, and Makemake to the list. My Very Excellent Mother Just Sent Us Nine Pizza Eggrolls & Hot Mustard.

If you drop the requirement for planets to be in orbit around the sun you can throw a few moons orbiting Jupiter and Saturn to the list — notably, Io, Ganymede, Callisto, and Titan. My Very Excellent Mother Just Invented Garlic Cheese Sauce That Undulates Nervously.

What you need to recognize, though, is that your new definition would still be completely arbitrary and driven mostly by the need to get to the number twelve. Once you start including dwarf planets it’s hard to come up with a good reason to exclude the smaller ones like Ceres, Gonggong, Orcus, Quaor, and Sedna. Once you start including moons you’re going to want to get the Moon on the list because, let’s be honest, it’s the best moon.

And you want to get the sun on there, too, well, good luck with that. You’re on your own.

Connections

The idea that there were twelve planets first surfaced in the background of “Lost Legacy,” our episode about the so-called Mitchell-Hedges Crystal Skull of Doom.

We briefly discussed George Hunt Williamson and his relation to “American Hitler” William Dudley Pelley in the episode “Seven Minutes in Heaven.”

If Zecharia Sitchin’s ideas sound familiar to you, that may be because cult leader and idea sponge Dwight York incorporated large chunks of them into the beliefs of his United Nuwaubian Nation of Moors, which we discussed in the episode “Space is the Place.”

Sources

- Adamski, George. Inside the Space Ships. Abelard-Schuman, 1955.

- Amadio, David. Rug Man. Paul Dry Books, 2023.

- Baum, Richard and Sheehan, William. In Search of Planet Vulcan: The Ghost in Newton’s Clockwork Universe. New York: Plenum Trade, 1997.

- Blavatsky, Helena P. The Secret Doctrine. Jeremy P. Tarcher, 2009.

- Boudry, Maarten. “The Hypothesis That Saves the Day: Ad Hoc Reasoning in Pseudoscience.” Logique et Analyise, Volume 56, Number 223 (July/August/September 2013).

- Colavito, Jason. The Cult of Alien Gods: H.P Lovecraft and Extraterrestrial Pop Culture. Prometheus Books, 2005.

- Comins, Neil F. What if the Earth Had Two Moons? And Nine Other Thought-Provoking Speculations on the Solar System. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2010.

- de Purucker, Gottfried. Fundamentals of the Esoteric Philosophy. Theosophical University Press, 1932.

- de Purucker, Gottfried. The Fountain-Source of Occultism. Theosophical University Press, 1974.

- Dreyer, J.L.E. History of the Planetary Systems, from Thales to Kepler. Cambridge University Press, 1906.

- Flaherty, Robert Pearson. “‘These Are They’: ET-Human Hybridization and the new Daemonology.” Nova Religio, Volume 14, Number 2 (November 2010).

- Gillett, Roy. The Secret Language of Astrology. Sterling Publishing, 2011.

- Grundhauser, Eric. “There is gold in seawater, but we can’t get at it.” Atlas Obscura, 23 Mar 2017. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/gold-ocean-sea-hoax-science-water-boom-rush-treasure Accessed 7/24/2024.

- Heiser, Michael. “Zecharia Sitchin: Why you can safely ignore him.” UFO and Paranormal News from Around the World, 3 Sep 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20171219111503/http://www.ufodigest.com/news/0909/ignore-him.php Accessed 7/26/2024.

- Heiser, Michael. Sitchin is Wrong. https://www.sitchiniswrong.com/ Accessed 7/24/2024.

- Heiser, Michael. “The Myth of a Sumerian 12th Planet: ‘Nibiru’ According to the Cuneiform Sources.” 2003.

- Heiser, Michael. “The Myth of a 12th Planet: A Brief Analysis of Cylinder Seal VA 243.” 2003.

- Jackson, Cass and Jackson, Janie. Astrology, Plain and Simple. Hampton Roads, 2005.

- Jastrow, Morris Jr. Aspects of Religious Belief and Practice in Babylonia and Assyria. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1911.

- The Koran. Penguin Books, 1956.

- Learn, Joshua Rapp. “The Asteroid Belt: Wreckage of a destroyed planet or something else?” Discover, 28 Jan 2021. https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/the-asteroid-belt-wreckage-of-a-destroyed-planet-or-something-else Accessed 7/26/2024.

- Leo, Alan. Esoteric Atrology. Destiny Books, 1983.

- Levenson, Thomas. The Hunt for Vulcan. New York: Random House, 2015.

- Lewis, Tyson and Kahn, Louis. “The Reptoid Hypothesis: Utopian and Dystopian Representational Motifs in David Icke’s Alien Conspiracy Theory.” Utopian Studies, Volume 16, Number 1 (Spring 2005).

- Lobo, Greenstone. “12 Zodiac signs & only 5 planets.” Saptarishis Astrology. https://saptarishisastrology.com/12-zodiac-signs-and-only-5-planets-by-greenstone-lobo/ Accessed 8/22/2024.

- Marrs, Jim. Our Occulted History: Do The Global Elite Conceal Ancient Aliens? William Morrow, 2013.

- Moorey, Teresa. The Numerology Bible: The Definitive Guide to the Power of Numbers. Firefly Books, 2012.

- Morrison, David. “The myth of Nibiru and the end of the world in 2012.” Skeptical Inquirer, Volume 32, Number 5 (September/October 2008).

- Morrison, David. “Update on the Nibiru 2012 Doomsday.” Skeptical Inquirer, Volume 33, Number 6 (November/December 2009).

- Newbrough, John Ballou. Oahspe: A New Bible in the Words of Jehovih and his Angel Embassadors. Oahspe Publishing Associates, 1882.

- Pilkington, Mark. Far Out: 101 Strange Tales from Science’s Outer Edge. The Disinformation Company, 2007.

- Plait, Phil. “The Planet X saga: the scientific arguments in a nutshell.” Bad Astronomy. http://www.badastronomy.com/bad/misc/planetx/nutshell.html Accessed 7/26/2024/

- Pratt, David. “The Twelve Sacred Planets.” David Pratte. https://davidpratt.info/sacredpl.htm#na8 Accessed 7/30/2024.

- Richmond, Maureen Temple. “The Threefold Rulership System in Esoteric Astrology.” The Esoteric Quarterly, Winter 2018.

- Richter, Jonas. “Traces of the Gods: Ancient Astronauts as a Vision of Our Future.” Numen, Volume 5, Number 2/3 (2012).

- Schilling, Govert. The Hunt for Planet X: New Worlds and the Fate of Pluto. Springer Science + Business Media, 2009.

- Sitchin, Zecharia. The 12th Planet. Bear & Company, 1991. (orig. 1976)

- Sitchin, Zecharia. The Stairway to Heaven. Bear & Company, 1992. (orig. 1980)

- Sitchin, Zecharia. The Wars of God and Men. Bear & Company, 2002. (orig. 1990)

- Sitchin, Zecharia. The Lost Realm. Harper, 2007. (Orig. 1990)

- Sitchin, Zecharia. When Time Began. Harper, 2007. (Orig. 1993)

- Sitchin, Zecharia. The Cosmic Code. Harper, 2007. (Orig. 1998)

- Sitchin, Zecharia. “What If?” Archeology, Volume 42, Number 1 (January/February 1989).

- Sitler, Robert K. “The 2012 Phenomenon: New Age Appropriatian of an Ancient Mayan Calendar.” Novo Religio, Volume 9, Number 3 (February 2006).

- Thomas, Paul Brian. “Revisionism in ET-Inspired Religions.” Nova Religio, Volume 14, Number 2 (November 2010).

- Thompson, William Irwin. Coming into Being: Artifacts and Texts in the Evolution of Consciousness. St. Martin’s Press, 1996.

- Van Den Berg, Hugo A. “”X Makes Nine: A Distant Ice Giant in the Solar System.” Science Progress, Volume 99, Number 2 (2016).

- Van Flandern, Tom. “An Astronomer’s Analysis of the Akkadian Seal.” Converation for Exploration, 5 Feb 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080205194138/http://www.lauralee.com/vanflan.htm Accessed 7/25/2024.

- Welfare, Simon. Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World. New York: A&W Publishers, 1980.

- Wheeler, Brannon. “Guillaume Postel and the Primordial Origins of the Middle East.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion, Volume 25, Number 3 (2013).

- Williams, Stephen. “Fantastic Messages from the Past.” Archaeology, Volume 41, Number 5 (September/October 1988).

- Williamson, George Hunt. Other Tongues, Other Flesh. Amherst Press, 1953.

- “Christian O’Brien v. Zecharia Sitchin: Comparing historical records.” The Golden Age Project. https://www.goldenageproject.org.uk/obrienvsitchin.php Accessed 7/24/2024.

- “Dwarf Planet.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwarf_planet Accessed 8/22/2024.

- “List of Solar System objects by size.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Solar_System_objects_by_size Accessed 7/24/2024.

- “The 12th Planet and Zecharia Sitchin.” Rational Skepticism. https://www.rationalskepticism.org/viewtopic.php?t=10141&start=20 Accessed 7/26/2024.

- “Zecharia Sitchin and our alien ancestors.” The Psychology of Extraordinary Beliefs, 1 Mar 2019. https://u.osu.edu/vanzandt/2019/03/01/zecharia-sitchin-and-our-alien-anecestors/comment-page-1/ Accessed 7/26/2024.

Links

- Sitchin Is Wrong

- Unidentified: Zecharia Sitchin’s Made-Up Ancient Aliens History

- Unidentified: Fear of a 12th Planet

- Unidentified: Nibiru Needs Gold (and Sperm, for Some Reason)

- 404 Media: If Planet X Exists, It’s Running Out of Places to Hide

- David Amadio’s Rug Man (it’s great!)

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: