The Terror of Gillikin Country

they terrorized the rust belt for years, and the cops were none the wiser

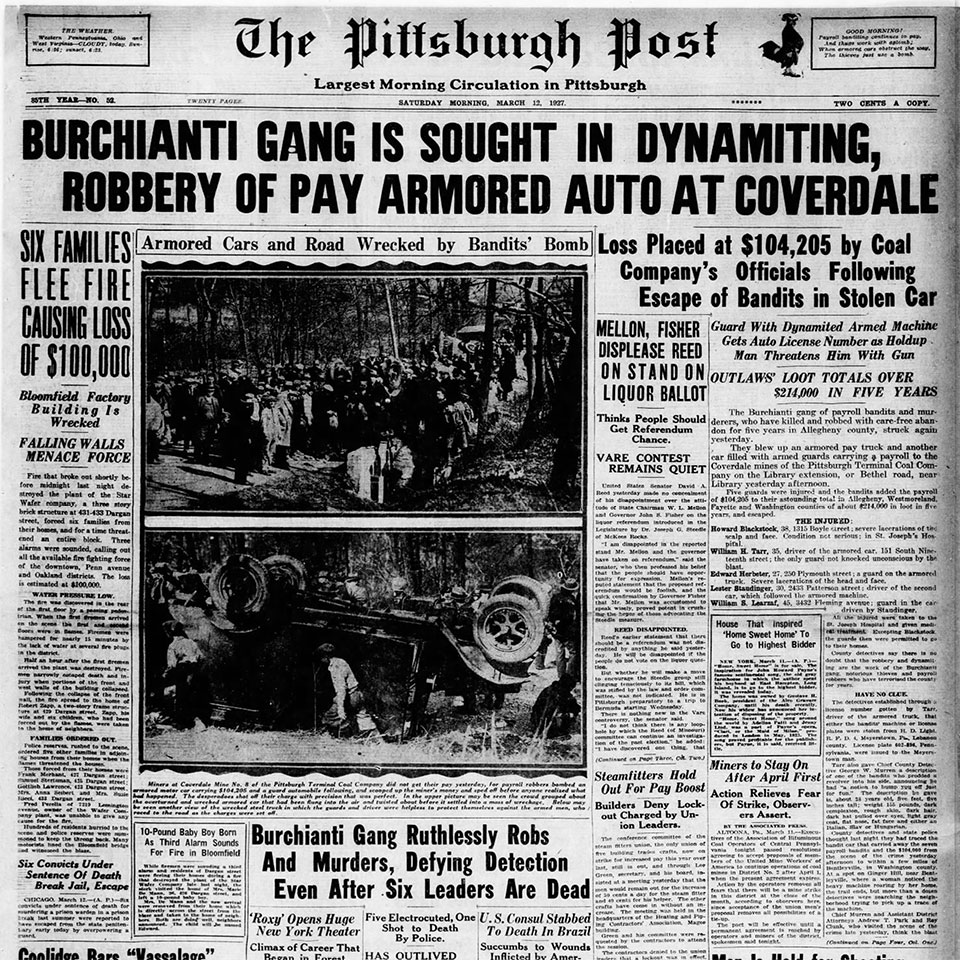

On Friday, March 11, 1927 a Brinks armored truck and its escort vehicle made their way through the south hills of Pittsburgh. They were carrying the payroll for the Pittsburgh Terminal Coal Company’s Coverdale mine.

The convoy turned off Library Road onto an extension that went to the mine. Suddenly, a tremendous explosion went off beneath the armored truck. It was hurled 75 feet through the air and came to a rest upside down with the rear doors blown off. Another explosion went off in front of the escort vehicle, which drove right into the four foot deep crater and could not drive out.

As the dazed and injured guards struggled to get their bearings, six armed men wearing flat caps and jumpsuits emerged from the woods. The robbers relieved their victims of weapons — mostly pistols and shotguns, but also a machine gun that had been on hand just in case of an assault just like this. One of the bandits, a cruel-looking thug with a broken nose, taunted the injured men with his pistol, and announced he was entertaining a notion to bump them off just for fun.

Then, the bandits turned their attention to the loot. They tore open the mangled doors of the armored truck and stripped its contents with surprising efficiency. A few minutes later the robbers were speeding away in their getaway car, having stolen the strangely precise sum of $103,834.38.

It was the Great Coverdale Payroll Robbery, the first successful armored truck robbery in history.

(Just to be clear: armored trucks had been robbed plenty of times. The novelty of the Coverdale robbery was that the crooks struck while the cash was still in transit, instead of just jumping the guards after they’d started to unload their cargo.)

The injured guards limped onward to the Coverdale mine, where they were loaded into trucks and rushed to nearby St. Joseph’s Hospital. The mine managers started frantically calling for help to no avail — the telephone lines running to the mine had been knocked down by the explosion.

When the cops finally arrived, the robbers’ trail was cold as ice. It didn’t matter. The cops already knew who was responsible: the Torso Burchianti Gang.

The Torso Burchianti Gang

The Burchianti Gang had been terrorizing the Monongahela Valley since 1921. They specialized in industrial payroll robbery, the bigger the payroll, the better. Their jobs were incredibly risky, but the huge payoffs meant the gang could lay low for months as they planned their next heist.

The gang’s members were all experts in their fields: safecrackers, sharpshooters, demolition experts, and getaway drivers. Tony “Torso” Burchianti was the de facto leader, not because he was smart or cunning, but because he was reckless and ruthless. His attitude set the tone for the gang. They never hesitated to shoot a resisting victim, an interfering security guard, or even an innocent bystander who happened to get a glimpse of a gang member’s face. Collateral damage and the loss of innocent lives didn’t bother them in the least.

Reckless and ruthless they may have been, but the Burchiantis were also professionals. You had to catch them red-handed, because otherwise they always seemed to have airtight alibis. They were cool as a cucumber under interrogation, and never give up their accomplices.

The cops weren’t sure who was running with the gang these days. A life of crime is usually a short one, and the original six members were long gone. Jack Stummy had been shot during a caper. Pete Falier, Hugo Fiotti, Pete Sabri and John Torti had gone to the electric chair. Torso had been the last to go, and true to his nature, it was spectacular.

In 1924 the gang had planned an ambitious robbery: the $500,000 payroll of the Carnegie Steel Company’s Clairton mills. It was a simple plan: kill everyone in the passenger car of the train being used to transport the cash, then throw the steel safe off the side. But when the gang boarded the train on Pittsburgh’s South Side they realized it was packed full of cops and security guards. Clearly, their inside man had flipped on them. They called an audible and got off at the next stop.

But nobody could get word to Torso, who was idling further down the line in the getaway vehicle. He sped away when the guards started to disembark, and was caught after a thrilling high-speed chase. Shortly afterwards he convicted of felony murder in an unrelated crime and sentenced to fry. He went to the chair on June 1, 1925, chomping a cigar and calling the warden every Italian vulgarity he could think of.

The Great Coverdale Payroll Robbery

Torso’s gang soldiered on without him. They pulled several other jobs the subsequent years, and the Coverdale robbery showed all the signs of a typical Burchianti caper.

The demolition equipment used in the heist had been stolen a few days previously from a PTCC mine in nearby Mollenauer. The crooks had spent hours digging up asphalt, planting their homemade charges, and then meticulously patching the road so no one would notice the work. They left inconspicuous piles of newspaper on the side of the road to help them work out their timing. And they’d cut the telephone wires to slow the inevitable call to the cops. That last one had been unnecessary, as it turned out, but still, the sign of a professional job.

The crooks had a sizable head start. By now they could be halfway to Buffalo or Detroit, preparing to cross the border into Canada.

The cops had virtually nothing to go on. Known gang associates like Dan Rastelli and John Burchianti were hauled in for questioning, but they were tight-lipped as usual. The only real clue was the model and plate number of the getaway car, a blue Stearns-Knight, PA 602-595, but even that looked like a dead end. The crooks had switched plates with a different car.

But over the weekend the cops got a lucky break.

A woman in rural Washington County told the police she had seen a blue Stearns-Knight go up a dead-end street on Ginger Hill… and never return. After a quick search the cops found the getaway vehicle at the bottom of a nearby ravine, with the stolen machine gun in the back seat. The bandits had backed it up to a barbed wire fence, pushed it into the ravine, and erased their tracks tracks. They’d even patched the fence so no one could see where they’d gone off road. (Again, total pros.)

The cops expanded their search area to include Washington County. It turns out the Stearns-Knight had been spotted making trips to a general store in Bentleyville. Some discreet questioning allowed the cops to track it back to a dairy farm owned by one Joe Weckoski. According to neighbors, Weckoski seemed to have an awful lot of money for a man with a failing farm. Recently he’d had visitors, who had been driving back and forth from his farm to the city at all hours.

That was all the police needed to hear. They surrounded the Weckoski homestead, quietly corralled Joe’s wife Sophie and his six kids, and surprised two men hiding out on the second floor. Stanley Melowski was napping in a cot. Joe Smith was counting a stack of crisp new bills. Smith glanced over at two .45s sitting on the table as the cops rushed up the stairs, only to think better of it.

Then they hunkered down and waited for Joe Weckoski to return. They may have been a little too obvious about it. Shortly after dark a vehicle started to turn up the drive, but the driver spotted the patrol cars by the house. He quickly backed up and sped off down the road. The car was later found abandoned on Pittsburgh’s North Side.

Joe Weckoski may have eluded their dragnet, but the cops were finding plenty of evidence around the farm. There were shotguns and ammunition aplenty. Stolen dynamite and fuses were found hidden in the woodshed. A calendar in the trash had the pay schedules of nearby mines clearly marked.

The cops really liked Joe Smith as a suspect. He had a broken nose, like the thug who had threatened the Brinks men. The bills he’d been counting had serial numbers that matched the ones stolen in the robbery. Even better, he had a bank passbook in the name of “Stanley Stanko” with suspicious deposits that lined up with previous Burchianti jobs. Then a Pittsburgh detective identified “Smith” as Paul Palmer, a two-bit hood who’d jumped bail after getting a chest full of buckshot after a failed saloon robbery in Sharpsburg. They aggressively grilled Smith for hours, thinking they could break the dumb Hunky. But Smith was a wall. He gave them nothing.

Then the cops got a telegram from Detroit. Police there had seen the APB on Smith and identified him as one Paul Jawarski, alias “Paul Topps” or “Paul Poops.” Jawarski was wanted for killing a police officer in a Hamtramck bank robbery. The cops showed Smith the telegram, and he broke.

He admitted to being Paul Jawarski. And he started to confess everything.

Unfortunately for the cops, “everything” was exactly what the Pennsylvania police didn’t want to hear.

Kings of Quendor

Paul Paluszynski was born in the Ukraine, but his family emigrated to America when he was still a child. The family bounced around the Rust Belt before settling down in Detroit, where they shortened their name to “Pallas.” Later Paul would later adopt the surname “Jawarski” to hide his criminal antics from his parents.

Paul and his siblings Sam and Lucille witnessed their father’s slow steady decline, brought on by hours of backbreaking labor in the mines and mills. The three of them swore that wouldn’t happen to them. They would live the easy life and get it the easy way, through crime. They formed their own gang, the Flatheads, named after the flat caps and jumpsuits they wore on the job.

The Flatheads first struck on July 15, 1921 when they boarded an interurban streetcar between the Pennsylvania towns of Charleroi and Donora. They forced the driver to stop the car near Eldora Park and then turned their attention to their real target: two employees of the Youghiogheny & Ohio Coal Company, carrying the $40,000 payroll for a nearby mine. Naturally, they resisted so Paul Jawarski shot one of them in the head. That convinced the other one to give up the goods. The Flatheads cut the power cable for the streetcar and nearby telephone lines, and then fled in a waiting car. The police had nothing to go on. The knew it had to be an inside job, because the payroll was about an hour ahead of schedule, but interrogating the mine employees proved fruitless. Every other lead proved to be a dead end.

In the years to come, this crime would be attributed to the Burchianti Gang. (To be fair to the cops, it did fit their M.O. The felony murder that sent Torso Burchianti to the chair had been committed during a very similar streetcar robbery.)

Eight months later, on March 11, 1922, the Flatheads jumped the paymaster of Pittsburgh’s Bernard Gloeckler Company as he returned to his office after a trip to the bank. They relieved the paymaster of his $7,000 burden and hopped into a waiting car. That car was later found abandoned on Stanwix Street in downtown Pittsburgh, but the Flatheads were long gone. The cops had no other leads.

The police later attributed this crime to the Burchianti Gang. (Mostly because it was a payroll robbery.)

On December 22, 1922 the Flatheads ambushed a convoy carrying the payroll for the Pittsburgh Coal Company’s Harrison mine. As the convoy made its way down Beadling Road, Paul Jawarski stepped out of the woods with a shotgun and blasted their armed escort, John Ross Dennis, right off his motorcycle. When the dazed Dennis started to reach for his revolver, Jawarski kicked him back to the ground and shot him in the back of the head. Then the Flatheads disabled the rest of the convoy, snagged the $20,000 payroll, and fled in a waiting car. That car was later found abandoned near Charleroi, stripped of any useful evidence.

The cops wouldn’t give up this time, though, since there’d been a murder. A few days later they rounded up a handful of rough types who had suddenly come into money: Thomas Duggan, John Burchianti, Louis Lieri, Orlando Fabbri, Frank Rostrelli, and Dan Rastelli. The surviving victims positively identified the six men as their attackers, and Rastelli was singled out as the murderer because he had a broken nose. (Just like Paul Jawarski.)

Fortunately for these six men, the prosecution was a regular comedy of errors. Dugan, Lieri and Rostrelli had airtight alibis and all charges agains them had to be dropped. The cases against Burchianti and Fabbri went to trial, where it turns out they also had excellent alibis but didn’t speak English so good and had been railroaded by the cops. They were found innocent of all charges. Dan Rastelli was convicted and sentenced to death, but an honest judge threw out all the circumstantial evidence against him and overturned his conviction. The cops fumed at this perceived miscarriage of justice, but there was nothing they could do.

This crime, too, was attributed to the Burchianti Gang. (Mostly because one of the men they’d arrested had the not-terribly-uncommon last name “Burchianti.”)

After the Beadling payroll robbery, Paul Jawarski decided to take it easy for a while. He got married, had a kid. But growing families need money, and Paul Jawarski only knew one way to make money.

The People’s National Bank of Hamtramck, MI was in one of the safest places possible: directly across the street from police headquarters. But police headquarters emptied out on March 4, 1924 when fire alarms went off all across the city — decoys set off by the Flathead Gang. In the confusion, three masked men tried to rob the bank. Things went south real fast. One of the bandits was shot by a teller, who set off the silent alarm. Two patrolmen rushed to the scene and fatally wounded another robber. The sole survivor, Paul Jawarski, was forced to flee empty-handed. And he added yet another line to his rap sheet: during his escape, he shot Sgt. Frank Boza through the neck, killing him instantly.

This crime was not attributed to the Burchianti Gang. (Mostly because it had taken place in Detroit, and the Michigan cops didn’t seem to have the tunnel vision their Pennsylvania counterparts had.)

Just over a month later, on April 30, Jawarski and an accomplice stormed into a Sharpsburg, PA saloon and emptied the register. But when they turned to leave, the bartender called after them, saying that he hadn’t given them everything just yet. Curious, Jawarski turned around… and received a shotgun blast to the chest at point blank range. His accomplice fled into the night and was never seen again. The critically-injured Jawarski was arrested and rushed to a nearby hospital. It didn’t look good. But amazingly, he made a recovery. He gave the cops a fake name, “Paul Palmer,” was charged with attempted robbery, and then, astoundingly, released on $4,000 bail. Which he promptly jumped.

On August 18 three Flatheads walked into an illegal after-hours bar, a “blind pig,” on West Elizabeth Street in Detroit and started waving their guns around. Unfortunately for them, Detective Frank Hage of the Detroit PD was at that very moment trying to buy a used car from the bartender. Hage drew his service revolver and chased the crooks out of the saloon and down the street. When one of the robbers tripped, Hage stopped to reach for his cuffs. Paul Jawarski took advantage of the opening and shot Hage straight through the heart, killing him instantly.

No one attributed these crime to either the Burchanti or Flathead Gangs, because they were small potatoes.

On November 11 Jawarski was hiding out in Chicago with four other criminals when police started firing tear gas through the windows. The men were rounded up and Jawarski was positively identified as “Paul Topps,” wanted for questioning in the murder of Detective Frank Hage. Jawarski was shipped back to Detroit, questioned, but never charged.

All in all, 1924 was a very bad year for Paul Jawarski. He resolved that next year would be very, very different.

On November 20, 1925 five Flatheads walked into the offices of the Ainsworth Manufacturing Company in Detroit. They forced the employees to be quiet and then ambushed two Brinks armored guards as they dropped off the company payroll. The Brinks men put up more of a fight than expected, so the Flatheads decided to cut their losses and flee with only a portion of the payroll. (Which was still a considerable $18,000.) Jawarski vented his frustrations during the firefight, killing one of the guards, Ross Loney, with a blast from a sawed-off shotgun.

Finally things were starting to go Paul Jawarski’s way.

The Flatheads’ next job was even bigger. On December 24, 1925 a payroll train stopped in Mollenauer, PA, loaded down with the payroll and Christmas bonuses for the Pittsburgh Terminal Coal Company’s No. 3 Mine. As the paymaster and two guards carried the money away from the train, the Flatheads burst on the scene in a speeding car and began firing wildly. One of the guards, Isaiah L. Gump, was shot in the stomach and bled to death. The other guards were quickly overwhelmed by superior numbers, and the bandits fled with the entire $48,000 payroll.

Police were on the scene almost immediately, and they knew just who to arrest: Dan Rastelli and John Burchianti, who lived nearby. The two men may have gotten a pass for the Beadling robbery, but the cops knew guilty when they saw it. But once again Rastelli and Burchianti proved to have ironclad alibis. As did every other Burchianti associate the cops called in for questioning: Sam Evola, Frank Feeny, Harry Lagos, Robert Sickles, Nick Silver, Dominic Simone, and “Italian Joe” Zardanelli were all clean as a whistle. Suspiciously so.

Damn, those Burchiantis were slick.

Meanwhile, the Flatheads were laughing all the way to the bank, just as they had for years. Well, not all of them. Flathead Jack Wright started grumbling to Paul about his share of the loot, so Jawarski addressed his grievances like a true leader. He shot Wright and dumped his body somewhere it would never be found.

(Here’s a bizarre sidebar to the Mollenauer robbery: the Flatheads had to steal two getaway vehicles. First they stole a car off the street in East Liberty, but it turned out to belong to Secretary of the Treasury Andrew W. Mellon. That was too hot even for the Flatheads, and they abandoned the car on Cherry Way downtown.)

And that brings us back to the present: March 1927. Paul Jawarski confessed to all of these crimes as he led the cops to $33,061 in hidden in a milk can buried in a manure pile under a cherry tree on the Weckoski farm.

Needless to say, the Pennsylvania cops were not happy. Their tunnel vision had allowed the Flathead Gang to operate for years, because they’d been ascribing all of their crimes to another gang with a similar modus operandi. All that time and money wasted running down Burchianti associates and harassing poor, innocent Dan Rastelli. It made them look like fools.

It was a small consolation that this time, at least, they’d caught the right person.

For a while Jawarski seemed to cooperate. He gave the cops info on Weckoski, and the name of four other confederates. Names that later turned out to be fake, but hey. He pled guilty, sparing the state the expense of a trial. And he was even willing to plead guilty to the Beadling and Mollenauer hold-ups, but only on the condition that he be executed as soon as possible.

That set off alarm bells. Prosecutors rejected the deal, rightly suspecting that Jawarski was trying to silence himself so he couldn’t be milked for more information. So they convicted him the old-fashioned way, and left him to rot away in the Allegheny County Jail waiting for the governor to sign his death warrant.

Concentrated Brains, Extra Quality

On August 18, 1927 Paul got a surprise visitor: his brother, Sam Pallas. They had a short chat in the visitor’s room. And then Sam rushed the guards and somehow managed to get two .45 automatics to his brother. Paul took one for himself and then threw one to his cell-mate, John Vasbinder, a drug-crazed psycho who had shot man in McKeesport for not giving him a quarter. The three men then shot their way out of the prison, wounding two guards, and into a waiting car driven by an unknown woman.

Another first for Paul: the first successful escape from the Allegheny County Jail that wasn’t an inside job.

Sam was picked up in Hamtramck at the end of September and sent to jail for organizing the breakout. Paul’s sister Louise was also pulled in for questioning, since she was suspected of being the getaway driver, but the cops couldn’t make anything stick. Paul remained at large.

On June 6, 1928 he struck again. Five Flatheads burst into the office of the Detroit News in the middle of the morning, threatening the employees and looting the paper’s $18,000 payroll. They shot their way out through two policemen (one of whom, George Barstad, died) and started a high-speed chase and running gun battle through the streets of downtown Detroit before escaping in the general direction of Ohio.

It sure looked like Paul Jawarski was back, and thinking bigger than ever.

But he screwed up. On September 13, 1928 he was dining out in the open in a Cleveland eatery when one of the other patrons recognized him — they had sung together in a church choir as kids. Soon the cops were on the scene, only to be greeted by shots from Jawarski’s gun. He killed patrolman Anthony Wieczorek, wounded patrolman George Effinger, and then ran out the back door, shooting an innocent bystander in the groin for good measure. He fled through back alleys, with the cops in close pursuit, before barricading himself in a residence on Chambers Avenue. The cops flushed him out with tear gas and then blasted him with a shotgun as he stumbled out the front door.

He begged for the cops to finish him off, but they were determined to see justice done. They drove him to the hospital in an armored car, surrounded by cops with machine guns and gear gas. Paul laughed at the sight, and taunted them: “Ain’t you glad I got out of jail? Look at the trip you get.” As he recovered from his wounds he confessed to even more crimes, even claiming to have killed 26 men, including John Vasbinder and several other wanted criminals. (The cops could only verify ten kills — they thought the others were a trick to stop them from searching for Flathead associates.)

Rather than waste money on a murder trial, Ohio extradited Jawarski back to Pennsylvania on the condition that they execute him right away. On January 21, 1929 he went to the electric chair in Rockview Prison. He tried to go out like Torso Burchianti, with a cigar in his mouth, but the warden refused.

Shortly before his execution, Paul Jawarski sent the district attorney one final message confessing to a few more miscellaneous crimes. He signed it off in the most badass way possible:

“See you at 49 Hell’s Fire Road. 10 Miles Beyond Hell.”

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

Other famous residents of Philadelphia’s legendary Eastern State Penitentiary include John Blymire, the York County hex murderer (“Bound in Mystery and Shadow”); child kidnapper William Westervelt (“Your Heart’s Sorrow”); and Joseph Peters of the Blue-Eyed Six (“Make Insurance Double Sure”).

This is the second of two episodes to feature a brief appearance by a member of the Mellon family. The Flatheads stole the car of Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon. Andrew’s son, Paul, would eventually front Yale University the money to buy the fraudulent Vinland Map (“Westward Huss”).

Sources

- “The Flathead Gang.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Flathead_gang. Accessed 4/22/2020.

- “Mollenauer PA (Mine No. 3)” Coal Camp USA. http://www.coalcampusa.com/westpa/pittsburgh/montour3/mon3.htm. Accessed 4/24/2020.

- “Paul Jaworski.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Jaworski. Accessed 4/22/2020.

- Capo, Fran and Bruce, Scott. It Happened in Pennsylvania; Remarkable Events That Shaped History. Guildford, CT: Rowan and Littlefield, 2011.

- Sebak, Rick. A Short History of Route 88. 2018. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=94jJNLXyNgg&feature=emb_title

- “Car bandits escape after shooting man and stealing $40,000.” Pittsburgh Press, 16 Jul 1921.

- “Payroll bandits elude pursuers, flee with $10,000.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 12 Mar 1922.

- “Nine payroll bandits and slayers elude police.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 24 Dec 1922.

- “Officers chase many blind leads.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 25 Dec 1922.

- “Three payroll murder suspects nabbed.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 30 Dec 1922.

- “Three identified as Beadling holdup men.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 10 Jan 1923.

- “Dennis murder trial may go to jury tonight.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 8 Jun 1923.

- “Two of three defendants in payroll case found innocent.” Pittsburgh Press, 15 Jun 1923.

- “Second outlaw in bank holdup hovers close to death.” Detroit Free Press, 5 Mar 1924.

- “Burchianti to be given over to local police.” Scranton Times-Tribune, 10 Apr 1924.

- “Bar proprietor opens fire as he gives cash.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 1 May 1904.

- “Detective, hijacker slain in down-town pistol duel.” Detroit Free Press, 18 Aug 1924.

- “Kin’s target practice cost detective’s life.” Detroit Free Press, 19 Aug 1924.

- “Tear gas bomb takes fight out of bandit gang.” Belvedere Daily Republican, 11 Nov 1924.

- “1 dead, second hurt in $18,000 payroll theft.” Detroit Free Press, 21 Nov 1925.

- “Bandits elude police after killing payroll guard.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 25 Dec 1925.

- “Payroll killing laid to executed bandit’s gang.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 26 Dec 1925.

- “Sleuths believe auto found Downtown used by payroll bandits.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 27 Dec 1925.

- “Burchianti gang sought in dynamiting, robbery of pay armored auto at Coverdale.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 12 Mar 1927.

- “Burchianti gang ruthlessly robs and murders, defying detection even after six leaders are dead.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 12 Mar 1927.

- “Two arrested in pay holdup; bandit auto found.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 13 Mar 1927.

- “Payroll bandits believed to have fled state.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 14 Mar 1927.

- “$30,000 of mine pay loot found.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 16 Mar 1927.

- “Weckoski confesses plot in Coverdale Mine holdup.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 17 Mar 1927.

- “Jaworski names four as Coverdale bandits.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 20 Mar 1927.

- “Prayers of Dan Rastelli answered when Jaworski clears his name of crime.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 20 Mar 1927.

- “Murderers escape county jail.” Pittsburgh Press, 18 Aug 1927.

- “Hold suspect in jail case.” Pittsburgh Press, 1 Oct 1927.

- “Galloping ghosts of the coal fields.” McAllen Daily Press, 13 May 1928.

- “$20,000 bandits make good escape; officer near death.” Detroit Free Press, 7 Jun 1928.

- “Jawarski boasts of killing 26 men.” Pittsburgh Press, 14 Sep 1928.

- “Eldora holdup confessed by Paul Jawarski.” Pittsburgh Press, 21 Sep 1928.

- “Jawarski bids farewell to wife and babe.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 19 Dec 1928.

- Lytle, William G. “Jawarski goes to death in chair.” Pittsburgh Press, 21 Jan 1929.

- “$500,000 pay theft foiled.” Pittsburgh Press, 11 Jan 1947.

- “Jawarski gets 8 to 16 years.” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, 8 Apr 1947.

- Sprigle, Ray. “My biggest stories: Boss of the Flathead Killers.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 3 Apr 1949.

- “The Great Detroit News Payroll Robbery.” Detroit News. 30 Apr 2000. http://blogs.detroitnews.com/history/2000/04/30/the-great-detroit-news-payroll-robbery/ Accessed 4/22/2020.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: