Westward Huss

Minnesota Vikings can be found far beyond U.S. Bank Stadium

This is part two of a three part series on the Viking relics of North America. It is not necessary to read all three parts to understand the story (but it can’t hurt). Part one, on the quest for Vinland in New England, can be found here. Part three, on fraudulent Viking relics in Oklahoma and the rest of the country, can be found here.

Okay, so where did we leave off last time?

In the mid-19th Century, some scholars and antiquarians began to theorize that Icelandic explorers had settled in New England several centuries before Christopher Columbus.

Several different groups latched on to this theory to further their own goals. In Europe, you had Scandinavians trying to enrich their history and establish a cultural link to the United States. In America, you had a WASP elite looking to replace Columbus as the “discoverer of America” as a way of asserting cultural dominance over Catholics and southern European immigrants. (And also to rewrite Native American history and culture to soothe their guilty conscience.) And of course there were also just contrarians and kooks building castles in the sky.

There was only one problem: none of them could find evidence of the Viking settlements anywhere. So to bolster their arguments they began misinterpreting historical documents and artifacts, or, in some cases, faking them. Finally, after more than a century of searching in vain, a lone Viking settlement was discovered in the 1960s… a thousand miles away from where everyone had been looking, and far smaller than anyone had anticipated.

Now, while all this was going on, you had another group of scholars and antiquarians pursuing a parallel line of thought. If they Vikings had reached New England… why would they have stopped there? Perhaps they had ventured even further into North America, not to settle, but to explore and trade like the coureurs des bois of New France. It was possible that Vikings had explored vast swaths of North America, including portions of central Canada and the upper Midwest of the United States.

Of course, this second theory had the same problem as the first: a complete and total lack of physical and documentary evidence. Unsurprisingly, its proponents came up with the same solution.

Making stuff up.

Inventio Fortunatae (14th Century)

Some of the earliest “evidence” rolled out for extensive Viking explorations of North America are a series of maps produced in the 16th century. They often have surprisingly detailed outline of the North American, including a large inland sea along the Arctic coast. Which is to say, they show Hudson Bay some fifty fears before it was ever sighted by Henry Hudson.

How did European mapmakers know about Hudson Bay, if no European explorer had yet to see it? The answer is simple: they copied it off earlier maps made by Gerardus Mercator. (Hey, if you’re going to steal, steal from the best.)

Well, then, how did Mercator know about Hudson Bay? He read about it in a book called the Inventio Fortunatae. The Inventio Fortunatae, or “The Fortunate Discovery,” recounts the travels of a Franciscan friar who traveled to Greenland in the mid-14th Century, armed only with his faith in Christ and an astrolabe, to survey the country and the lands beyond. After years of service, he compiled a weighty tome filled with details of the Arctic regions based on personal observations and reports from the locals. Or, at least, it’s supposed to be filled with details of the Arctic regions. Mercator never actually saw the Inventio Fortunatae. In fact, no one has in over five hundred years.

Still, he had the next best thing, a detailed summary of the Inventio that appeared in another book, the Itinerarium of Jacobus Cnoyen. A book that no one has seen in over four hundred years.

At least we have Mercator’s summary of Cnoyen’s summary, which he thoughtfully included in a letter to English astronomer and magician John Dee. Except, well, that summary is filled with all sorts of wild untruths. It mentions a giant mountain of magnetic rock at the North Pole, surrounded by a circular sea and the four islands of the “Hyperborean continent.” Its descriptions of the Arctic coastline are fanciful at best. Oh, and it claims Greenland was colonized by King Arthur.

Looking back on Mercator’s maps and the copies thereof, it turns out that “surprisingly detailed” is not the same as “surprisingly accurate.” Errors just start leaping out at you. There’s the presence of Hyperborea, for starters. The shape of North America and Asia’s Arctic coastlines are all wrong. The shape of Greenland is all wrong. Major islands and archipelagos, like Baffin Island, Ellesmere Island, and Svalbard are completely missing.

And “Hudson Bay?” Well, Mercator’s maps do have an inland sea, but it’s a perfect circle reached by a big river that goes due south. His imitators have altered the contours to make them a little more naturalistic, but the basic shape remains and it’s not the shape of Hudson Bay. It only looks like Hudson Bay to us because we’re expecting it to be there.

The Inventio Fortunatae, if it ever existed, sounds less the true tale of a holy man on a map-making mission and more like a series of fanciful extrapolations from classical sources like Strabo, Plutarch, and Pliny the Elder. It’s almost certainly not proof that the Vikings — or anyone from Europe — extensively explored North America before the 16th Century.

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye (18th Century)

How about the travels of 18th Century explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye? He was one of the first Europeans to travel west of the Great Lakes, and there are tales of his travels that seem to imply that Viking explorers reached the Canadian heartland. Specifically, alternative archaeologists like to cite his encounters with the Mandan or “white Indians,” and his discovery of a mysterious inscribed stone.

In New France, La Vérendrye and others started to hear tales of the Mandan, a light-skinned, blonde-haired, blue-eyed race Native Americans with strange cultural practices. These tales inspired scholars to all sorts of irresponsible speculation, much of it tied into the racist idea that there was a white “Mound-Builder” civilization that predated Native American settlement of North America. Perhaps the Mandan were the surviving remnants of this long-lost race of white men. They could be the only living descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, the Welsh followers of Prince Madoc, or, you guessed it, the Vikings of Vinland. Even if the Mandan weren’t predominantly white, perhaps they had interbred with the long-lost white race through the cultural practice of “walking with the buffalos” — essentially, offering up their wives to visitors.

There’s only one problem with such speculation: La Vérendrye had actually found the Mandan out along the Missouri River… and was disappointed. Based on the descriptions passed along by travelers, he had expected to find a strange race of white men living in seclusion out in the wilderness. What he found, though, was a group of Native Americans, not with light skin but lighter skin. “Blonde hair” turned out to be gray hair. No blue eyes anywhere to be seen. And their “strange cultural practices” weren’t actually all that strange. La Vérendrye didn’t think they were appreciably different from any other group of Native Americans he had met.

The travelers’ tales he had heard were just that, tales.

All of the differences that set the Mandan apart are pretty easily explained away. Their lighter skin pigmentation was due to their agricultural lifestyle, which meant they spent less time under the sun than their nomadic neighbors. The grayish hair seems to be a genetic predilection for achromotrichia (a fancy scientific way of saying “gray hair”). Modern genetic testing doesn’t seem to think the Mandan are significantly different from any other tribe of Native Americans. Their cultural practices only seem strange to Europeans used to dealing with the eastern tribes like the Iroquois, and did not reflect any sort of long-lost ties to Jewish or Christian religious practices.

There is absolutely no truth to the idea that a race of white men lived on North American shores in pre-Columbian times, as much as 17th and 18th Century racists might have wished otherwise.

More intriguing is the tale of the Vérendrye Runestone.

In 1738, while wandering central North Dakota, La Vérendrye stumbled across an unusual monument: several giant pillars of stone leaning up against each other, like a giant stone tipi. Inside the enclosure was another stone pillar with a niche carved into it, and in that niche was a stone tablet, covered on both sides with strange writing. Intrigued, La Vérendrye and his sons broke the stone free and brought it back to Quebec. There, several Jesuits declared that the stone was covered in “Tatarian characters” and shipped it off to Jean-Frédéric Phélypeaux, Compte de Maurepas in Paris for further study.

What, exactly are “Tatarian characters?” Did the Jesuits mean some sort of near-Eastern script, like Old Hungarian or the Old Turkic Orkhon script? Scripts that bear an uncanny resemblance to, dare I say, Viking runes? We’ll never know, because after arriving in France the tablet vanished, never to be seen again.

Assuming it ever existed in the first place. Most contemporary account of La Vérendrye’s expeditions do not mention the story, save one: the works of Swedish naturalist Pehr Kalm, who recounts a conversation he had with La Vérendrye towards the end of the latter’s life. If we assume that Kalm didn’t outright invent the conversation (and he seems to be generally trustworthy), it’s hard to explain why he’s the only one who’s heard this tale. Was he a victim of bad translation and poor memory? Was La Vérendrye just pulling his leg? Was there a conspiracy by the Jesuits and the French to cover up potential Turkish claims to North America?

Unless the tablet shows up, well, your guess is as good as mine. And since we’re just throwing out outlandish theories, well, I’m not saying it’s aliens, but…

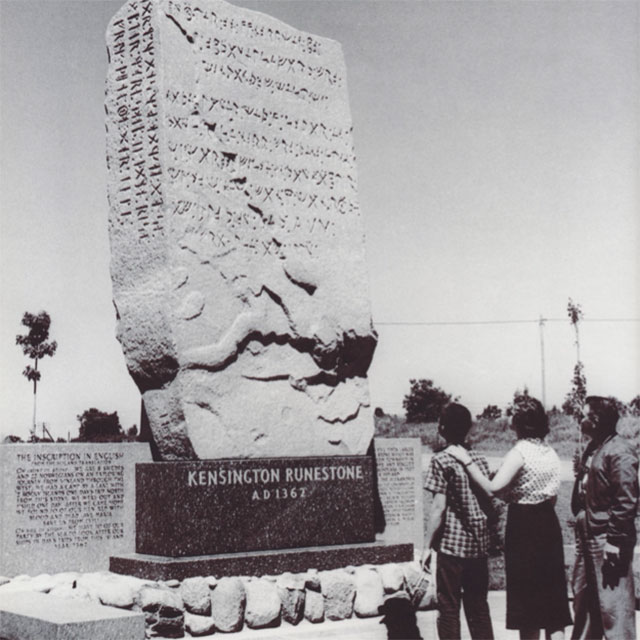

The Kensington Runestone (1898)

The idea of Vikings in the Midwest didn’t really get a proper kickoff until 1898. In that year Olof Ohman, a Swedish immigrant living in Douglas County, Minnesota, was clearing some fields on his farm. Entangled in the roots of one of the trees he uprooted was an oddly rectangular stone.

At first, Ohman thought nothing of it. Later, his 10 year-old son Edward came over with some hot coffee for his pop and though the stone looked a bit odd. Edward used his cap to beat away some of the dust and revealed several lines of what appeared to be a runic inscription. The two Ohmans puzzled over what they’d uncovered, and even called in a few of their neighbors, farmer Nils Flaten and cobbler Hans Moen, to take a look.

The stone was some 202 pounds of Minnesota graywacke, 2½’ high, 16” wide, and 5” thick, crudely cut into a roughly rectangular and relatively flat shape. Along one of the “faces” and down one of the “edges” was a lengthy inscription in some sort of strange characters, with what looked like a few Latin characters thrown in for good measure. Ohman and Flaten thought they might be some sort of Native American petroglyphs.

Thinking the stone would be a fun curio to show off, the two men gave it a thorough cleaning and hauled it to the nearby town of Kensington, where it was exhibited in a bank window for several weeks. Some locals agreed with Ohman and Flaten that the carvings were Native American in origin. Others thought it might be some sort of secret code used by robbers giving directions to their buried treasure, which lead to a brief spate of hole-digging on nearby farms. And still others thought they looked more like Scandinavian runes.

In January 1899 real estate agent John P. Hedberg wrote a letter about the stone to a Swedish language newspaper in Minneapolis, and included a copy he’d made of the transcirption. Intrigued, the editors forwarded Hedberg’s letter to the foreign languages department of the University of Minnesota. Ultimately, it made its way to Olaf Breda, professor of Scandinavian languages.

Breda confirmed that the characters were indeed runes, and presented a coherent message in Swedish. The inscription along the face read:

Eight Gotalanders and 22 Norwegians on reclaiming journey from Vinland to west. We had a camp by two skerries one day’s journey north from this stone. We were fishing one day. After we came home we found 10 men red from blood and death. AVM save us from evil.

The shorter inscription down the side read:

There are 10 men by the sea to look after our ships fourteen days journey from this island. Year 1362.

Breda was intrigued by the stone. But he thought it was troubling for a few reasons.

- First, the runes were a strange mixture of archaic runic forms that died out hundreds of years before 1362 and newer runic forms that were just then coming into fashion. You might expect to see one or the other in the same document, but not both.

- Additionally, the umlauts on the runes correspond to their use in modern Swedish orthography, which is not identical to their use in Old Swedish.

- The grammar of the inscription was bad, but that was hardly a deal-breaker. However, it also used several anachronistic terms such as othdagelsfard (“voyage of discovery”) and dagh rise (“day’s journey”).

- The mixture of runes, Arabic numerals and Latin text was also puzzling and highly unusual, if not unprecedented.

For these reasons and several others, Breda declared the stone was most likely a modern hoax. Still, he thought it was worthy of further study.

The next scholar to investigate the Kensington Runestone was Professor George O. Curme of Northwestern University in March 1899. Curme was excited by the possibilities of such an exciting find and champing at the bit to declare it genuine. But when Curme actually got a chance to see the runestone in person, he was troubled by the same irregularities that had troubled Breda and the fact that the copy of the inscription he had been sent was not identical to the inscription on the stone itself. After further consideration, he too decided that the stone was actually a modern hoax but forwarded information about it to his colleagues, seeking a second opinion.

Rasmus Bjorn Anderson, head of the Department of Scandinavian Studies at the University of Wisconsin and one of the leading disciples of Carl Christan Rafn, took one look at the stone and declared it to be a hoax. That means something, because Anderson would believe anything — you may remember that in our last episode he was proclaiming the Fall River Skeleton to be the corpse of Thorvald Eriksson!

The final blow was the report of several professors from Christiana University in Sweden who declared that the stone was a hoax, the hoaxer seemed to have a deficient knowledge of Old Swedish and runic forms, and what’s more, could barely handle a chisel.

With an array of the world’s greatest experts on Scandiavian history and runology arrayed against it, the Kensington Runestone soon dropped out of the news cycle. Olof Ohman reclaimed it from the bank window and used around the farm as a doorstop.

There it stayed until 1907, when Olof Ohman met Hjalmar Holand for the first time.

Hjalmar Rued Holand had emigrated to the United States as a teenager to go live with his older sister in Wisconsin. He proved to be a bright lad and industrious student of history, earning a Masters degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1899.

Holand was not a big fan of academia. He felt professors were so far removed from the common people that they had lost touch with reality. That feeling only deepened after he heard multiple lecturers describe the lives and motivations of immigrants in a way that didn’t match the lived experience of Holand or anyone he knew. Even so he continued to play the game, working diligently on what would eventually become a multi-volume history of the Norwegian experience in America.

Along the way, though he fell under the sway of Carl Christan Rafn, Bjorn Rasmus Anderson and others who argued that the Vikings had settled in America centuries before Columbus. Holand took their fringe theories one step further. He insisted that not only had the Vikings settled the New England coast, they had also traveled through the Canadian Arctic all the way to modern-day Minnesota and Wisconsin.

It’s hard to say what motivated Holand to make this strange intellectual leap. To play armchair psychiatrist, it seems that Holand, having emigrated as a teenager, still held a deep nostalgia for his homeland and sought to relieve that nostalgia by making homeland and adopted country the same place. After all, if the United States was a country built and settled by Scandinavians, well, then, it was as good as home. And if the Scandinavians predated the Anglo-Saxons who currently ruled the roost, well, even better.

If genuine, the Kensington Runestone provided hard evidence that Vikings had reached Minnesota some time in the 14th Century. Holand hand-waved away all the previous academic objections to the stone’s authenticity made it the centerpiece of his 1908 book, De Norske Settlements Historie. He even concocted an origin story for the stone.

In 1347 a ship full of Greenlanders crashed on the shores of Iceland, and sent a panicked report back to Europe that the Greenland settlements were slowly dying. Concerned, in 1354 King Magnus Smek of Sweden issued a royal proclamation sending one of his lieutenants, Paul Knutsson, to travel to Greenland, assess the situation, and do what he could to correct the problem. Holand believed the Kensington Runestone had been carved by members of the Knutsson expedition. Clearly things had gone badly, with half of their party being massacred by agents unknown. The surviving members carved the Kensington Runestone as a record of their travels, and turned back.

These outlandish claims came under fire almost immediately. And there’s good reason to doubt them.

First, any original documents relating to the Knutsson expedition have been lost to history. King Magnus’s original order is only known by references to a later 16th Century copy, and even that copy was destroyed by a fire in the early 18th Century.

There’s also no proof that Knutsson even left Sweden. It would be highly unlikely that he had, given that the Black Death was decimating the population of Scandinavia at that time. If Knutsson survived the plague, he would be needed more in Sweden than in Greenland.

If the Knutsson expedition had launched, it was astounding that it wound up in Minnesota, thousands of miles away from actual Norse settlements in Greenland and Newfoundland. The stone’s carver claims to be on a “voyage of discovery” though that doesn’t line up with Knutsson’s royal remit to fix the problems in Greenland.

Even more astounding the carver of the stone claims to be only 14 days from the sea, which is incredible. The shores of Hudson Bay may only be 900 miles away as the crow flies, but that would be a journey involving multiple lengthy portages and sailing upstream through unknown and barely navigable waterways.

The story presented on the stone makes no sense. Okay, you’re a Viking on an exploratory mission in unknown territory and you come back to camp to find half of your men have been murdered. Let’s spend the next few precious hours carving a runestone to tell your story to a search party that is probably not ever coming.

And finally, no matter how much he might like to, Holand couldn’t just hand-wave away previous objections to the stone’s authenticity. He had to address them.

Holand would spend much of the next 40 years addressing these criticisms and battling with far more respected scholars of Scandinavian history and langauges including Johan A. Holvik and Erik Wahlgren. Holand’s academic credentials couldn’t match those of his opponents, but he had one thing they didn’t — the single-minded obsessiveness of a crank.

First, he endeavored to prove that the Kensington Runestone was indeed a legitimate find and not planted. In 1909 he marched Olof Ohman and Nils Flaten down to a notary public and had them swear out affidavits recounting the story of the stone’s discovery. Holand considered the affidavits unassailable, though that was far from true. They were suspiciously full of detail given that they were made a full decade after the events they recount. The grammar and wording of the affidavits doesn’t sound like the natural speech or writing patterns of Ohman or Flaten, suggesting they had been heavily edited by a third party, likely Holand. There are minor inconsistencies between the affidavits, like the exact date when the stone was discovered. (August or November?)

And it’s not like there have never been fraudulent affidavits before. Ohman in particular had incentive to lie about the stone’s origins, since he and Holand were actively trying to sell it to the Minnesota Historical Society for the astronomical sum of $5,000 dollars.

To that, Holand responded that Ohman was little more than an ignorant peasant too simple to lie and too unskilled to carve runes. That does Ohman a great disservice, since from every other account he was a reasonably clever and intelligent man. A clever and intelligent man who also owned a copy of a Swedish-language encyclopedia with lengthy sections on the Old Swedish syntax and runology. As for “too simple to lie?” It doesn’t jibe with the memory of his neighbors, who remembered that Ohman liked a good practical joke and had once declared “he would like to figure out something that would bother the brains of the learned.”

To critics who claimed he could not prove the Knutsson expedition ever happened, he countered that they could not prove it didn’t happen either. That, at least, put both sides at an impasse.

To explain the vast amounts of territory that the Knutsson supposedly covered, Holand theorized that water levels had been far, far higher years ago and also that Knutsson and his men had switched from Viking longboats to Native American canoes. He was right about the water level, but not to his credit credit. The area around Ohman’s farm had been a swampy marsh until farmers began to drain it in the mid-19th Century.

The canoe thing also didn’t jibe with one of Holand’s other arguments, that the area was filled with “mooring holes” that had been used to anchor their ships. You don’t need to moor a canoe — you can just pull it up on to the land. The placement of mooring holes make even less sense than the ones Frederick J. Pohl discovered on Cape Cod, since they were all at vastly different levels. There’s also the matter of why you would bother to waste time carving mooring holes if you are only passing through.

Even Holand had to concede there was no evidence the Vikings had actually settled Minnesota. Repeated archaeological surveys of the area did not turn up any artifacts, either Swedish or Native American. Again, not surprising since the area had previously been a swamp.

As for issues with the stone’s carving and language, Holand once again hand-waved most of those away. Recent scholarship has actually vindicated Holand’s stance here a bit, suggesting some of the archaic runic forms may survived in isolated communities, and that some of the anachronistic words and phrases may have originated far earlier than previously thought.

To try and get some academic muscle on his side, in 1911 Holand took the stone to Europe and showed it to every scholar of Scandinavian language and history he could find. It didn’t work. Scholars in France, Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Norway all declared the stone a modern fabrication. He experienced more success back home when the Minnesota Historical Society declared the Kensington Runestone to be genuine. They didn’t buy it, as Holand had hoped, because it turns out the title was total mess and it was unclear who actually owned it.

Over the years the Kensington Runestone became a colorful piece of Minnesota pseudo-history that no one outside of Minnesota actually believed in. It was exhibited at countless Minnesota state and county fairs; in 1948 at the Smithsonian Institution; in 1949 at the Minnesota Centennial exhibition in St. Paul; and at the Minnesota pavilion 1964 New York World’s Fair. In 1951 parts of Ohman’s farm were turned into “Runestone Memorial Park” and the Runestone itself is on permanent display at the Runestone Museum in nearby Alexandria.

After Holand died in 1963, a different class of crank got wider access to the stone and theories really started spiraling out of hand.

In 1967 the Kensington Runestone was studied by Dr. Ole G. Landsverk and Alf Monge, who had developed a theory that every genuine runic inscription also included deliberate irregularities that constitute a sort of Baconian cipher hiding the date it was encoded. They claimed to have found the date “April 24, 1362” encoded in the Kensington Runestone’s inscriptions. Others have been largely unable to duplicate their findings, and everyone questions why the Vikings would ever bother hiding significant dates in plain sight.

In the early 2000s the stone was investigated by the Kensington Runestone Scientific Research Team. One of the Team, geologist Scott Wolter, made a detailed analysis of the stone and, based on weathering patterns, declared it to be at least 400 years old.

There is the slight problem that Wolter’s chosen field of “archaeopetrography” is practiced by only one person — Scott Wolter — and like most forensic science his techniques have never been peer-reviewed or seriously tested.

There’s also the bigger problem that Wolter is also a conspiracy theorist, who suggests that the secret purpose of the Knutsson expedition was to transport and bury the secret treasure of the Knights Templar somewhere in North America. To support this, he claims that there are micoscopic punch marks on certain characters of the stone spelling out an additional message:

Grail, these 10 (men have) Wisdom, (the) 10 (men are with the) Holy Spirit.

Amazing how Landsverk and Monge missed that one.

Look. There are just some phrases where, once you hear them, you know the author is full of crap. Those phrases include things like “Knights Templar” and “Holy Grail” and “buried treasure.” To hear them so many of them in the same story is mind-boggling.

All of this seems less like it comes from a place of genuine belief, and more like Wolter was angling to get his own show on the so-called History Channel. If so, it worked. He was the host of the pseudo-archaeology show America Unearthed for 39 episodes from 2012 to 2015, and again for another 10 episodes when it was revived on the Travel Channel in 2019.

At this point it seems unlikely we’ll ever know who carved the Kensington Runestone unless someone finally invents the necrophone. It’s clearly a fraud — there are just too many irregularities to be ignored. But who perpetrated it? And why? These are questions we’ll never be able to definitively answer.

The Beardmore Relics (1930)

In case you couldn’t tell from that lengthy summary, the Kensington Runestone is the elephant in the room here. It’s so big, in fact, that it leaves little room for other so-called relics when it comes to the debate about a possible Viking presence in the upper Midwest. That didn’t stop these “relics” from occasionally popping up, though most of them were transparently fake, planted by people looking to reverse-engineer a local ethnic presence or make a quick buck.

A prime example would be the sword plowed up in a field in Ulen, Minnesota in 1911. For decades locals claimed it was the discarded weapon of some long-forgotten Viking settler, perhaps even Paul Knutsson himself. The sword itself, though, was clearly not a medieval design and was quickly revealed to be a mass-manufactured theatrical prop that could be mail-ordered out of an 1882 catalog.

More intriguing are the relics discovered in 1930 by freight conductor and part-time prospector James Edward Dodd of Port Arthur, Ontario. While working a claim on the shores of Lake Nipigon near the town of Beardmore he unearthed a strip of old rusty iron that turned out to be a broken sword. More digging turned up an axe, and a strip of bent metal.

Dodd was fascinated by the items, but also broke. He tried to sell them as genuine Native American artifacts. That didn’t work, so he began to do some research and discovered that it was tradition for a Viking warrior to be buried with a broken sword. (The practice had largely died out by the time the Vikings reached the New World, but we’ll let that slide.) Belatedly, he realized he may have been digging into the grave of some long-lost Viking explorer.

Unable to sell the items locally, in 1936 Dodd sent sketches of the items to the Royal Ontario Museum. Dr. C.T. Currelly, the Museum’s Curator of Archaeology, immediately recognized them as genuine Viking artifacts: a sword, an axe, and a shield handle. Curran offered to buy the lot for $500, and Dodd jumped on the offer. He even tossed another scrap of iron he found on a later dig, which he claimed to be a part of the shield.

Everyone agrees the Beardmore relics are 100% genuine Viking artifacts, though Currelly’s identification of them is wanting. The so called “shield handle” is actually a rangle, a jangling instrument hung from a horse’s harness to make noise and drive away evil spirits. What the scrap of iron is, that’s anyone’s guess.

What people can’t agree on is whether the relics were actually found near Beardmore.

Shortly after the relics were sold, Dodd’s foster son Walter and his co-worker Eli Ragotte came forward to reveal the truth behind their discovery. The artifacts had not been dug out of a lonely grave on the shores of Lake Nipigon, but found in 1928 while cleaning out the basement of a house Dodd had rented in Port Arthur. Walter Dodd even remembered the address: 33 Machar Avenue.

That house belonged to one J.M. Hansen, and yes, he had admitted to having some weird old artifacts in the basement. He had taken them as security for a loan to Jens Bloch. Bloch, an amateur antiquarian, had collected the items in Norway and brought them to Canada when he emigrated in 1923. Bloch had yet to repay the loan when he died in 1936. Hansen didn’t know where they had got off to. He admitted they looked similar to the Beardmore relics, though of course he hadn’t laid eyes on them for years and they had been professionally restored in the meantime.

There was also the slight matter of the erstwhile discoverer. It turns out James E. Dodd was known to have a slight problem with the truth, to the point where his friends called him “Liar Dodd.” (His friends called him that!) Case in point, that “shield boss” he recovered on a later trip back to Lake Nipigon? Yeah, that trip never happened. Dodd hadn’t been back to the claim since 1930. And it wasn’t even his claim.

Unfortunately, the large Norwegian community of Port Arthur had caught Viking fever and were quite extremely proud of their home-grown artifacts and their newly important position in Canadian history. Ragotte, Hansen, and Walter Dodd were forced to recant their statements under intense public pressure.

Still, the truth will out and eventually word leaked out to the general public. The relics are still on display at the Royal Ontario Museum — they are genuine historical artifacts, after all — but no one presents them as proof that Vikings once roamed the shores of Lake Superior.

Well, except for the kooks.

The Spencer Lake Mound (1935)

Woof. That was long too. Let’s try something short and sweet.

In 1935, a team of archaeologists from the University of Wisconsin were excavating Native American burial mounds near Spencer Lake, Wisconsin. In the course of their joyful grave-robbing they dug up some 58 peacefully resting Native Americans, countless artifacts… and one horse skull.

This was more than curious. American horses went extinct near the end of the Miocene Epoch, some 10 million years ago, and were only reintroduced to the continent by the Spanish in the 16th Century. So what was a horse skull doing in a Native American burial mound that was dated to approximately 1000 AD?

Say it with me: Vikings!

Clearly, the established dates for the mound were wrong, and not only had the Vikings settled the coastline of North America but they had made it all the way to Waupaca, Wisconsin. And they’d brought horses with them!

Or maybe not. Shortly after the skull was unearthed, two local men approached archaeologist Ralph Linton and claimed to have planted the skull years earlier as teenagers. Apparently they thought it was a funny prank to play on the archaeologists of the future. Linton brought the story to the head of the dig, W.C. McKern, who brushed off any concerns and insisted the soil around the skull had been undisturbed.

In the meantime, of course, Viking fever broke out and locals began rewriting the history books to trumpet the Viking settlement of Wisconsin. The pranksters only took their story to the public when the Milwaukee Public Museum planned a major exhibition of the Spencer Lake artifacts in 1962.

In spite of the public confession, Viking proponents held out on this one for a few more decades. Finally, in 2001 radiocarbon dating established that the skull was thoroughly modern and the history books had to be un-rewritten.

The Sauk Center Altar Rock (1943)

On the plus side, the good people of Thunder Bay and Waupaca actually have some relics to point to. The good people of Sauk Center, Minnesota just have holes.

Four of them, to be exact, in a big ol’ boulder. They are roughly triangular and not unlike the “mooring holes” found by Hjalmar Holand around Kensington or by Frederick Pohl on the shores of Follins Pond. You would be forgiven for thinking that perhaps some farmer started drilling with the end goal of blasting the boulder away, then took a second look at the sheer mass of this big chungus and thought better of it.

But when Hjalmar Holand and the good people of Sauk Center rediscovered the rock in 1943, they knew better. Clearly Viking explorers — perhaps even the fabled Paul Knutsson — had used the boulder to celebrate Mass, making it one of the earliest Christian churches in America. The thought is apparently that two of the holes, which are horizontal, were used to provide support to an altar, while the two holes that are vertical were used to support an awning of some sort.

I have no idea how the Holand and the people of Sauk Center got all that from a bunch of holes in a rock. Seriously. I spent weeks researching this and didn’t see any sort of evidence whatsoever being presented. Apparently they all just knew somehow, through the Akashic Record or something.

In any case, there are the usual problems with this theory. If the Vikings had settled in the area, why has no other evidence of their habitation been found? And if they were just passing through and stopping to celebrate Mass, why did they bother to drill the damn holes in the first place?

Meanwhile, the boulder hit the big time in the 1970s, when the local chapter of the Knights of Columbus began to promote it as the “Sauk Center Altar Rock” and celebrate Catholic Masses there. Which sounds like the sort of thing a hip young youth pastor would try out to boost flagging attendance for the early Sunday folk Mass.

Also, is it funny that a fraternal order named after Christopher Columbus actively promoted the view that Vikings beat him to the New World by 500 years? Or is it just me?

In any case, the Viking masses seem to have died down after only a few years. There’s still not a shred of evidence whatsoever that the Altar Rock was a temporary Viking church, but that doesn’t stop the faithful from believing.

Elbow Lake Runestone (1949)

Here’s another short but sweet one.

Sometime in 1944, Victor Setterlund uncovered a 75 pound, heart-shaped rock covered with runic inscriptions while making a footpath on his farm near Barrett, Minnesota. It made quite a stir across the state and noted authorities, including Hjalmar Holand and J.A. Holvik, were called into investigate. Everyone agreed that the inscription read, “Four maidens camped on this hill” accompanied by a hard-to-read date.

Hjalmar Holand thought that date was 1362, but he also thought the stone was a hoax. The inscription felt too fresh, and too inconsequential.

J.A. Holvik thought the date was 1776, but rather rely on guesswork he took the simple expedient of directly asking Victor Setterlund was it supposed to be. Setterlund sheepishly confessed to carving the inscription himself and said that it was supposed to be 1886 but he’d botched the carving.

At least Setturland had the final word on his brief moment in the sun. “It sure doesn’t take much to put some people on if they want to believe you bad enough.”

Vic, you don’t know the half of it.

AVM Runestone (2001)

On May 13, 2001, two members of the Kensington Runestone Scientific Testing Team were conducting a survey of the land near Runestone Park. They were about a quarter of a mile from the spot where Ohman purportedly unearthed the stone, when they thought they spotted an inscribed rock on a nearby island where local farmers were tossing boulders pulled out of their fields. They took some photos and returned a few weeks later. This time, the cleared away moss and lichen to discover the date 1363, the Latin inscription “AVM” and a runic inscription reading “Christ the Savior conquers.”

Well. That was enough for the Scientific Testing Team. They returned a week or so later, winched the rock out of its position and onto the hood of a 1971 Chevy Imaala, and used a duck boat to float it over to shore. They began cleaning the stone and hired a team of archaeologists to examine the nearby area.

On August 11th they announced their find to the general public and claimed that the second inscription not only proved the authenticity of the Kensington Runestone, but the idea that the Vikings had extensively settled Minnesota.

There were problems from the beginning, of course. The general scientific community was extremely skeptical. Geologists pointed out that the land where the stone was located, along with most of the surrounding area, would have been underwater in the 14th Century. The archaeological survey turned up a handful of Native American artifacts, but nothing remotely Norse. Another group of KRS enthusiasts claimed to have spotted the stone in the mid-1990s and dismissed it as a fraud. Despite these setbacks, the Scientific Testing Team remained hopeful.

Alas, the stone was totally debunked when it was examined by Team member, geologist Scott Wolter. He cleverly noted that the iron pyrite exposed by the carving had not completely oxidized, meaning that that the inscription was relatively recent. Wolter’s announcement was less a finishing blow and more like kicking a dead horse, though.

You see, when the Scientific Testing Team began asking for donations to fund their further research, two former University of Minnesota Ph.D. students came forward and revealed that it was all a hoax. In 1985, Drs. Kari Ellen Gade (professor of Germanic Studies at Indiana University, Bloomington) and Jana K. Schulman (then professor of English at Southeastern Louisiana University, now director fo the Medieval Institute at Western Minnesota University), and three other friends attended a seminar on runic inscriptions. Afterwards, they discussed the Kensington Runestone and wondered if they could create a fake half as convincing. So a few weeks later they took a hiking trip, carved some runes into a rock, and then promptly forgot about for the next fifteen years.

Gade and Schulman came forward too late to prevent the KRSSTT from collecting the money and sending the stone to Wolter for testing, but they did come forward before he had announced his findings. Until that point, Wolter purportedly had “nagging doubts” about the age of the inscription but was still willing to vouch for its antiquity. After the revelation that the stone was fake, he had to extensively revise his report to make sure he didn’t look like a total ass.

Patriots 24, Vikings 10

The contrasts between the two strains of Viking fever are key to understanding them. In one area you have a beleaguered “elite” trying to strip away the symbolic power held by certain immigrants; in the Midwest you have other immigrants trying to integrate themselves into their adopted homeland’s history.

The similarities between the two strains are also fascinating. Because of a complete lack of supporting evidence, proponents wind up having to over-invest in the evidence they do have and mask the flimsiness of their arguments with spurious interpretations, wild leaps of intuition, arguments packed full of logical fallacies, and the personal charisma of their leaders. Over time that sloppiness leads both groups to get taken over by kooks, crazies and frauds.

Or rather, that’s how it goes when you’re trying to construct a narrative out of these stories. It’s far more likely that, just like their mythical North American Vikings, the kooks, crazies and frauds had been there all along and were just waiting for the moment to reveal themselves.

Connections

This isn’t a a connection to our podcast, but the Inventio Fortunatae and its giant magnetic rock show up in the latest series from the Constant on the history of longitude. Go check it out!

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye found a strange arrangement of stone pillars somewhere in central North Dakota. Sounds like a monument to the geographic center of the North American continent to me! We discussed the various geographic centers of North America in the Series 4 episode “The Centers of All Things.”

If you would prefer to read about the time Scandinavians actually tried to colonize the New World, check out Series 10’s “Nya Sverige” about the ill-fated colony of New Sweden.

Sources

- Feder, Kenneth L. Archaeological Oddities. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2019.

- Fell, Barry. America B.C. New York: Pocket Books, 1989.

- Goudsward, David. The Westford Knight and Henry Sinclair: Evidence of a 14th Century Scottish Voyage to North America (Second Edition). Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2020.

- Holand, Hjalmar R. America 1355-1364: A New Chapter in Pre-Columbian History. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1946.

- Holand, Hjalmar R. Westward from Vinland. New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1940.

- Kehoe, Alice Beck. The Kensington Runestone: Approaching a Research Question Holistically. Long Grove, IL: Waveland Press, 2005.

- Wahlgren, Erik. The Kensington Stone: A Mystery Solved. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1958.

- Wolter, Scott F. The Hooked X: Key to the Secret History of North America. St. Cloud, MN: North Star Press, 2009.

- Carpenter, Edmund. “Further evidence on the Beardmore relics.” American Anthropologist, Vol. 59 No. 5 (October 1957).

- Gilman, Rhoda R. “Kensington runestone revisited: recent developments, recent publications.” Minnesota History, Vol. 60 No. 2 (Summer 2006).

- Godfrey, William S. “Vikings in America: Theories and evidence.” American Anthropologist, Vol. 57 NO. 1 (February 1955).

- Hjorthén, Adam. “A Viking in New York: The Kensington Runestone at the 1964-1965 World’s Fair.” Minnesota History, Volume 63, Number 1 (Spring 2012).

- Hughey, Michael W. “‘Making’ history: the Vikings in the American heartland.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society, Vol. 2 No. 3 (Spring 1989)

- Liestøl, Aslak. “Cryptograms in Runic Carvings: A Critical Analysis.” Minnesota History, Volume 41, Number 1 (Spring 1968).

- Mancini, J.M. “Discovering Viking America.” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 28 No. 4 (Summer 2002).

- Moltke, Erik. “The Ghost of the Kensington Stone.” Scandinavian Studies, Volume 25, Number 1 (February 1953).

- Nielsen, Richard and Knirk, James E. “Forum.” Scandinavian Studies, Volume 73, Number 2 (Summer 2001).

- Michlovic, Michael G. “Folk Archaeology in Anthropologic Perspective.” Current Anthropology>, Volume 31, Number 1 (February 1990).

- Powell, Eric A. “The Kensington Code.” Archaeology, Volume 63, Number 3 (May/June 2010).

- Powell, Eric A. “Runestone Fakery.” Archaeology, Volume 55, Number 1 (January/February 2002).

- Snow, Dean R. “Martians & Vikings, Madoc & Runes.” American Heritage Magazine, Volume 32, Number 6 (October/November 1981).

- Springer, Karri L. “The Fact and Fiction of Vikings in America.” Nebraska Anthropologist, Volume 15 (1999).

- Sprunger, David A. “Mystery & Obsession: J.A. Holvik and the Kensington Runestone.” Minnesota History, Volume 57, Number 3 (Fall 2000).

- Trow, Tom. “Small holes in large rocks: the ‘mooring stones’ of Kensington.” Minnesota History, Vol. 56 No. 3 (Fall 1998)

- Wahlgren, Erik. “American Runes: From Kensington to Spirit Pond.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology, Volume 81, Number 2 (April 1982).

- Rath, Jay. “Wisconsin: The Baloney State.” Madison.com, 31 Mar 2007. https://madison.com/news/wisconsin-the-baloney-state-the-state-enjoys-a-rich-tradition-of-hoaxes-and-myths/article_72f826da-3adb-54f1-b1fc-19f56798cfd8.html Accessed 4/12/2021

- Williams, Henrik. “American Runestones.” Uppsala University, 30 Apr 2019. http://www.runforum.nordiska.uu.se/blog/american-runestones/ Accessed 4/12/2021.

- “AVM Runestone.” Fake Archaeology. http://www.fakearchaeology.wiki/index.php/AVM_Runestone Accessed 4/12/2021.

- “AVM Runestone.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AVM_Runestone Accessed 4/12/2021.

- “Inventio Fortunata.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inventio_Fortunata Accessed 4/12/2021.

- “Spencer Lake horse skull.” Milwaukee Public Museum. http://www.mpm.edu/index.php/node/27107 Accessed 4/12/2021.

- “Top Ten Viking Hoaxes.” The Viking Rune. https://www.vikingrune.com/2009/05/top-ten-viking-hoaxes/ Accessed 4/12/2012.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: