The Hot House

refining radium in the home, for fun and profit

Lansdowne is a small suburb in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, about a mile west of Philadelphia on Baltimore Pike. It’s just over a square mile in size, and has a population of about 10,000 people.

Over the years Lansdowne has had a number of famous residents: Pat Croce, former owner of the Philadelphia ’76ers; Olympians Bruce Harlan and Leroy Burrell; and musicians Joan Jett, Kurt Vile, and Jeff LaBar. And, of course, yours truly.

But no former resident left their mark on the community quite like Dr. Dicran Hadjy Kabakjian.

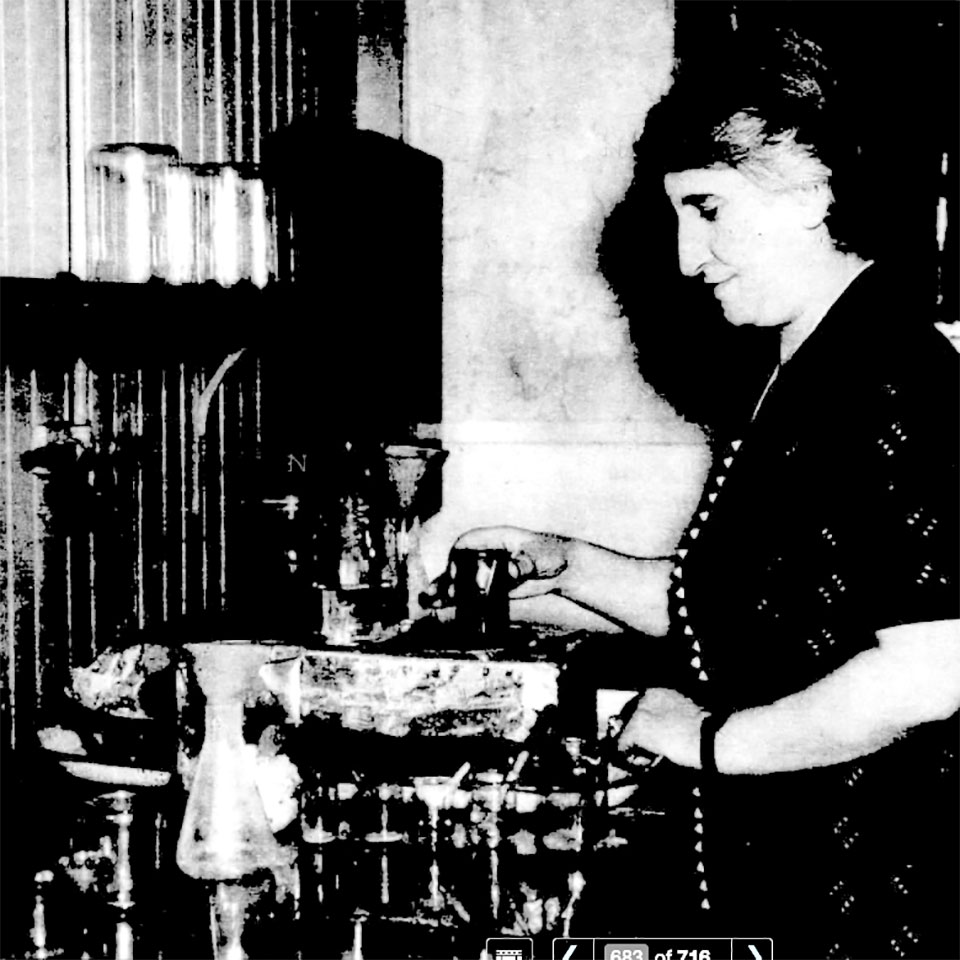

Dr. Dicran Hadjy Kabakjian (1875-1945)

Dicran Hadjy Kabakjian was born in 1875 in city of Yozgad in the Ottoman Empire. Though Ottoman by citizenship, Kabakjian was a proud Armenian by birth and throughout his life he remained active in Armenian causes and organizations. He was an advocate for Armenian independence following World War I and the Armenian Genocide, and an early member of both the Armenian Students Association and the Knights of Vartan.

Kabakjian had a passion for science and learning, and he soon realized that he would have to leave the Ottoman Empire to develop that passion. In 1906 he emigrated to the United States to study physics at the University of Pennsylvania. He received his Masters degree in 1907, his Doctorate in 1910, and was immediately hired by the University as a physics instructor. He became an assistant professor in 1914 and a tenured full professor in 1924.

In the early 1900s there was no more exciting field of study than radioactivity. It had only recently been discovered by the Curies, and every physicist was scrambling to make new discoveries in this strange new field and find practical applications for it.

Dr. Kabakjian was no different. He soon became one of the foremost authorities in the United States on radiation and radioactivity. Though he never made any exciting discoveries or thrilling theoretical leaps, he did solid work confirming others’ studies and expanding the bounds of science.

In 1913, Kabakjian developed a process for extracting radium salts from carnotite, a yellowish clay-like uranium ore mined in Colorado and Utah. Kabakjian’s process, which involved crushing the ore into a fine sand and treating it with strong acid, was far more efficient than the other processes in use at the time, extracting 90% of the radium from the ore. He sold the exclusive rights to this process to the W.L. Cummings Chemical Company of Lansdowne, which kept him on retainer as its “chief radium consultant.”

In 1915, Cummings set up a radium refining facility in Lansdowne, in a wooden building by the train tracks near the intersection of South Union and Austin Avenues. The company employed twenty-five workers, who operated powerful grinding and crushing machines, manually shifted the resulting sand piles into vats two stories tall, and applied chemical treatments to the sand. They also carefully measured the refined radium into small glass tubes, which were placed inside silver plated tubes, which were placed in nickel-plated iron tubes, which were put inside a heavy leather case and stored in a steel vault until they could be sold to researchers and doctors clamoring for radium. The facility processed up to two tons of carnotite ore per day, and its yearly output was three grams of radium — about the same mass as a penny.

That sounds like a lot of work for very little output, but remember two things. First, Cummings was one of only six radium-producing facilities in the entire world. And second, the price of radium was an astonishing $100,000 per gram (about $2 million today).

The business did quite well for a few years, and both Cummings and Dr. Kabakjian prospered. But nothing lasts forever. The market for radium underwent some changes in the early 1920s as richer ores were discovered, and Cummings could no longer compete despite the additional refinements Kabakjian made to his process. The Austin Avenue refinery closed for good in 1922 and the rights to the process reverted to the good doctor.

That put Dr. Kabakjian in a bind. He had moved his family into a beautiful three-story Victorian duplex at 105 East Stratford Avenue in Lansdowne, just to be closer to the refinery, and he really needed his “chief radium consultant” retainer.

Thankfully, he had a flash of insight. While the margins of his radium process no longer made sense for a small company, Kabakjian realized he could make them work for a smaller boutique company. So in 1923 the Kabakjian family started refining radium in the basement of their suburban home.

Every few months a truck would come by and drop a load of carnotite ore into the Kabakjians’ backyard. The Kabakjian boys, Armen and Raymond, would move the ore into the basement and grind it into sand. Even their daughters got in on the act. Alice would cook the sand until the radium crystals formed, Louise would weigh the crushed crystals and pack them into fine-gauge platinum needles, and Lillian kept the books. Dr. and Mrs. Kabakjian participated throughout the entire process. The radium-filled needles were sold to doctors and hospitals, for the then-new field of radiotherapy for cancer, and the income helped the Kabakjian family weather the depression.

In the 1930s, Dr. Kabakjian found another source of income. He developed a “radium finder” — a sort of homemade Geiger counter — and would use it to find radium that had been misplaced, for a fee. (Because apparently even when a material is worth tens of thousands of dollars a gram, people still can’t be bothered to keep track of it.) He found radium on the carpeted floors of doctors’ offices, in hospital trashcans and furnaces, and in cluttered laboratories and student workspaces.

During WWII any scientist with a background in radioactivity was drafted into the war effort, including Dr. Kabakjian . He provided radium to the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard so they could x-ray ship parts to find minute cracks and other imperfections.

But Dr. Kabakjian was getting old, and had to shutter the family business. He retired from active teaching in 1944, and died on November 13, 1945.

Because Dr. Kabakjian had spent decades working with radioactive material, he was given a thorough post-mortem examination to see if radiation had led to his downfall. Doctors determined he had indeed died from work-related causes — but not because of radiation. Fumes from the strong acids he used in his refining process had given him fibrosis of the lungs.

Joint Decontamination Project (1961-1965)

After Dr. Kabkjian’s death, his family no longer needed a giant three-story house. They sold 105 East Stratford Avenue to the Tallant family in 1949 and moved into a smaller home.

The Tallants were not aware initially aware of Dr. Kabakjian’s work with radium. When Anna Tallant heard about it from neighbors, she had a small panic attack. She brought glass vials she had found in the basement to the police, asking them to test the house with a Geiger counter. The police did not take her concerns seriously.

Eventually, the Tallants moved into an even larger home and sold 105 East Stratford to the Kizirian family in 1961.

In late 1950s and early 1960s, Pennsylvania spent a small fortune cleaning radioactive contaminants from a five-story office building Pittsburgh that had been used to produce radium. (That’s the Parkvale Building in Oakland, if any Pittsburgh residents want to have a panic attack now.) Worried about the negative publicity from the incident, the state tasked Dr. Jan Lieben of the Department of Health to practively track down old sites used to process radioactive material. Dr. Lieben did some research and came across the news about Dr. Kabakjian’s odd home business.

The Kizirian family was surprised when Department of Health investigators with Geiger counters showed up at their home. They were even more surprised when those investigators discovered that radiation levels in the house were far above what could be considered safe.

The basement, where most of the refining work had been done, was the most contaminated — one basement sink was throwing off so much gamma radiation that testers refused to approach within a few feet. But other rooms also showed significant contamination, including the first floor dining room, the front porch, the garage, and the driveway. The dangers in the house included gamma rays, radon gas created by the decay of radium, and fine radium dust that was everywhere.

The state ordered the Kizirians to clean the house up, but Harry Kizirian was then-unemployed and could not afford the estimated $10,000 cost. State and federal agencies were no help, because regulations regarding clean-up only covered military and industrial sites. Private residences were out of luck. The state Bureau of Radiation Protection was adamant: if the Kizirians couldn’t afford to clean up the house, they would have to demolish it.

So the Kizirians got a lawyer, Charles Basch. He wrote the Army, the U.S. Public Health Service, and the Joint Nuclear Accident Coordinating Center of the Defense Department, to no avail. Eventually Basch was able to get the ear of a friendly congressman, who was able to order a joint state-federal decontamination project led by the Air Force.

In 1964 crew of state technicians and Air Force personnel wearing respirators and contamination-proof coveralls descended on the Kizirian house. They removed almost 10,000 items the Kabakjians had left behind when they moved out, all covered in a fine coating of radium dust, along with large chunks of the concrete and wooden floors. Everything they couldn’t remove was sanded, scraped, power washed, and vacuumed to within an inch of its life and then given three thick coats of epoxy-based paint to seal in any contaminants that remained. (Tough you would think lead paint would have actually been fine, just this once.) Over 120 drums of contaminated material were shipped to a disposal site near Buffalo, NY.

As part of the clean-up, the Kabakjian and Kizirian families, along with others who lived or worked at the house, were tested at MIT, who found no long-term consequences to their health. The bodies of Dr. and Mrs. Kabakjian were also exhumed for testing, and the professor’s body was found to contain 5.7 micrograms of radium, at that time the largest amount of radioactive material ever detected in a human body.

The final clean-up costs were nearly $200,000, almost twenty times the original estimate. A follow-up study found the level of contamination had been reduced by over 90%, but also found that residents of the house would be exposed to an additional .5 rems of radiation per year over their normal environmental exposure. And while that’s was hardly going to give anyone radiation poisoning, it is certainly enough to increase the risk of cancer in long-term residents, especially lung cancer caused by the inhalation of radon gas and fine radium particles.

Dr. Lieben wrote to the U.S. Public Health Service, arguing that the Kizirians could not be allowed to return, that further clean-up activities were impractical, and that the house should be destroyed. He was overruled by the PHS’s Russell I. Pierce, who poo-poohed the dangers, noting that residents would only be in danger if they spent “16 hours or more per day at the house.” He was joined by Raymond Kabakjian, who declared, “This whole thing about radium has been blown out of proportion.”

In the end, the Kizirians moved back in to 105 East Stratford Avenue, and the radioactive house became a strange piece of local lore that was quickly forgotten.

Superfund (1983-1989)

After the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act of 1980 (CERCLA), the Environmental Protection Agency put out a call for state and local agencies to nominate toxic waste sites in their jurisdictions that might be eligible for thew new “Superfund” treatment. Someone in Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Resources remembered the old Kabakjian house and passed it along.

The EPA sent agents to 105 East Stratford Avenue to perform some tests and install radon detectors. What they found was terrifying, but they struggled at how to express it. At the time, there were no residential safety standards for radiation exposure.

Non-environmental exposure limits to gamma radiation for the general public were then set at .17 rem/year. A resident of the former Kabakjian residence would be getting a hefty dose of 1.6 rem/year, or about ten times the limit.

Tests of the soil outside the house turned up radium, thorium, actinium and protactinium in troubling quantities. Soil activity levels were estimated at 2800 picocuries per gram (pCi/g). By comparison, a level of 15 pCi/g would trigger safety reviews at a uranium mining facility.

The EPA also noted that “even with windows open for the summer, the first floor shows radon concentrations above what would trigger a remedial action at a uranium mill tailings site.” Exposure levels for uranium miners were limited to 0.3 Working Levels (WL) of radon gas. The exposure level in the former Kabakjian residence was estimated at 0.309 WL. And that was on the first floor. Levels in the basement were worse.

Now, to put these numbers in perspective, you get a dose of .1 rem from a chest x-ray, and the average human being is exposed to about .3 rem/year from environmental sources. Limits for occupational exposure are about 5 rems a year, with exposure not to exceed 3 rem per quarter.

So the levels of gamma radiation weren’t great, but weren’t likely to kill you immediately. The most worrying problems were the radon gas and radium dust inside the house, because once a radiation source gets inside your system, you’re toast. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) estimated that a lifelong resident of the house would have an increased risk of cancer about 8-10% higher than normal, and an increased risk of lung cancer 14-37% higher than normal.

And, just to back that up those statistics with some totally unreliable anecdotal evidence:

- Anna Tallant, who lived in the house from 1949-1961, died in 1969 of breast cancer at age 54.

- Dicran Kabakjian’s son, Dr. Raymond Kabakjian, who spent most of his formative years in the ouse, died in 1977 of abdominal cancer at age 65.

- Kabakjian’s grandson, Raymond Jr., died in 1983 of bladder cancer at age 37.

- William Dooner, who delivered carnotite ore to the Kabkjians home for two decades, died in 1984 of age 71 of lung cancer.

The EPA also sent agents next door to run tests on the other half of the house — oh, yeah, did you forget that the Kabakjians lived in a duplex? Well, so did everyone else, because the 1964 decontamination effort ignored that side of the house completely completely. Anyway, it turns out the situation at 107 East Stratford Avenue, while not as dire, was still well above federal safety limits. And remember, those safety limits were for mines.

As best as the EPA could figure, the 1964 clean-up did a great job, but left behind an infinitesimal amount of radium weighing less than a paperclip. It was even possible that the solvents used during cleaning had pushed that material deeper into the structure of the home, making it harder to remove and spreading contamination to the other side of the duplex. That was all it took for the house to slowly become a radioactive nightmare over the next 20 years.

There was only one solution. The house had to go. As a “hot” site in the middle of a residential neighborhood, it shot it to the top of the EPA’s priority list. They got a $100,000 allocation to relocate the remaining residents, commissioned a feasibility study for demolishing the house from the Argonnne National Laboratory, and installed additional security defenses, radon detectors and a fire detection system.

They tried to reassure the public. “The main problem is inside the house,” declared George Bochanski, director of regional public affairs for EPA. “We feel strongly that it does not present a problem to any neighbors or people on the street. If you’re standing on the sidewalk outside the house, the meter shows absolutely nothing.”

Those reassurances didn’t stop the press and public from going, um, nuclear. The 1964 clean-up efforts had been received with mild bemusement, but in the intervening 20 years anxieties about the dangers of radiation had only increased. The issue became the, um, hot issue in local politics, and played a huge part in Lansdowne’s elections in 1985 and 1987. It was enough to make you yearn for the boring days of PTA squabbles and municipal bond issues.

One particularly aggrieved group was the local Armenian community, who felt that the good doctor’s accomplishments were being pushed aside and his name dragged through they mud as the media created the portrait of a mad scientist with a callous disregard for his own safety and the safety of the community.

To some extent, they had a point. When Kabakjian started his home business, the long-term dangers of radiation were not fully known. Chemical fume hoods weren’t standard laboratory equipment until late in Kabakjian’s career, so he could be excused for not having one. Kabakjian even had his white blood count repeatedly tested and took a break from the business when it was low.

But there’s no denying Kabakjian plowed ahead with his work even after the dangers of radiation became better understood, thanks to the death of famous researchers and the sensational stories of the Radium Girls and Eben Byers. He had no real excuse for not changing his procedures later in life, when the dangers were more apparent.

The Kizirians were also not happy. They made noise about suing the EPA for driving an old widow out of her home, but eventually realized they didn’t have a leg to stand on.

The furor even reached Kabakjian’s alma mater, where his old laboratory had been transformed into studios for the art school. The building had been extensively decontaminated during the 1950s, but a new round of tests demanded by faculty and students found some hot spots that had to be addressed.

In the short term, the EPA’s biggest worry was fire. If the old wooden building were set ablaze the entire town and parts of nearby communities might be sprinkled with fallout. That was why the EPA had installed a state-of-the-art fire detection system. But Delaware County Fire Marshall George Lewis and Lansdowne Fire Chief Paul Wentzell specifically ordered the Lansdowne fire department to not fight any fires at the house, fearing for their safety.

In the meantime, the house sat behind a large fence, attracting gawkers and the curious, while the EPA tracked down bits of the Kabakjian’s furniture that had dispersed among relatives and friends after the doctor’s death.

The initial feasibility study from Argonne National Labs came back, estimating that it would cost almost $800,000 to remediate the property, which would entail dismantling the house, removing up to 20 tons of radioactive soil, and replacing the connection to the sewer lines. A later 1986 study pegged the cost at $6 million. (By comparison, the normal cost to demolish a three-story wooden residence was only $24,000, and a twenty-story skyscraper in Center City Philadelphia had been recently been demolished for a mere $2 million. And neither study took into account the $1.5 million the EPA had already spent guarding the house and commissioning feasibility studies.)

Clean-up work finally started in 1987. The neighborhood was put under 24-hour guard as workers in white bunny suits armed with Geiger counties and cleaning tools worked to seal up the house the house and pull it apart, brick by brick. As they dismantled the residence they discovered the problem was far, far worse than they had thought.

The EPA had initially expected much of the house to be clean, but the only part of the house that didn’t give off radiation was one recently replaced brick. Apparently, the acid fumes released during Kabakjian’s refinement process efficiently spread radium particles throughout the house.

The Kabakjians had also apparently used to put old newspapers on top of their workbenches to catch spills, and when they were done they would burn them in the fireplace, which spread the contamination further.

The family may have also tracked radium around the house with their shoes and clothes, which they did not change after working.

The back yard was a nuclear nightmare. Not only would it have been piled high with carnotite ore for years, but Kabakjian had also used it to bury lab waste, knowing it was too dangerous to throw out in the regular trash. So the yard was studded with small pits filled with discarded lab equipment, broken vials and discarded tailings. He’d also dug a few pit in neighbors’ yards, just for fun. The duplex’s lot and six neighboring yards had to be replaced, removing the earth to a depth of 9 feet.

Nearby trees also turned out to be radioactive, either from neighborhood squirrels tracking radium dust with their tiny little feet, or maybe just thanks to fallout from the chimney. Those trees had to be removed.

As they dismantled the garage, they learned from neighbors that Kabakjian had also stored old lab equipment in their garages, and those had to be dismantled as well.

The Kabakjians had also disposed of radioactive waste liquid by dumping it into a convenient laundry sink in the basement, and occasionally by flushing it down the basement toilet. That had contaminated the local sewer lines, necessitating the additional removal of some 240 feet of sewer mains.

By June 1989, the clean-up was finished. The final cost was $11.6 million, over ten times the original estimate. The house had turned into 1,430 tons of rubble, filling 460 shipping containers, which were sent off to a nuclear waste disposal site in Utah. The 4,000 tons of radioactive soil removed from the house filled another 878 shipping containers, and another 6,776 tons of clean soil were trucked in to replace them. And 246 feet of municipal sewer line had to be replaced.

But the Hot House was no more. It was finally over.

Austin Avenue (1990-1995)

Sort of.

See, the EPA had been so busy cleaning up Kabakjian’s home that they forgot about his workplace, the W.L. Cummings Chemical Company on Austin Avenue.

Well, not forget, exactly. They just made it a lower priority, at least until a local environmentalist took a stroll around it with a Geiger counter and took her results to the local papers. No surprise, she found significant levels of radioactive contamination.

The Austin Avenue refinery was demolished. And in the course of that, they made yet more discoveries.

The Kabakjian process produced a lot of waste sand containing trace particles of radioactive material. Kabakjian had been content to bury the sand in his backyard, but Cummings cleverly figured a way to turn waste into profit: he sold it to local contracting firms to make mortar, stucco, plaster, and concrete. Which meant that there were an unknown number of homes in Lansdowne and neighboring communities filled with radioactive plaster, known to contain radium, thorium, and possibly uranium.

EPA scientists spent weeks driving around in a specially equipped van, trying to detect houses with radioactive stucco from the street. They found 21 more sites, including a small cluster of them only four blocks from my childhood home. Nothing was nearly as bad as the Hot House — but a few of them came awfully close. The EPA repaired one contaminated house, demolished and rebuilt ten houses, and permanently demolished and relocated the residents of eight more.

And then it was finally over.

The astounding thing is how lucky Lansdowne was. The contamination was largely limited to the Kabakjian home, the Austin Avenue refinery, and the homes of a few unfortunates who bought concrete in 1920. No one was seriously harmed, and cancer rates thankfully remained low. It could have been much, much worse. And yet it still took fifty years and $70 million to ensure that Lansdowne was radiation-free.

Well, mostly radiation-free. Pennsylvania still has an enormous radon problem, and Lansdowne is no exception.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Sources

- “Why radium is expensive.” Tonkawa (OK) News, 7 Sep 1916.

- Kabakjian, Dicran H. Impregnation of Water with Radium Emanations. US 1309139, United States Patent Office, 16 May 1918.

- “Exclusive radium process perfected.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 26 Jul 1921.

- “Radium reclaimed by scientist from laboratory trash.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 Mar 1932.

- “Dr. Kabakjian, scientist, is dead.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 15 Nov 1945.

- “EPA to Evacuate Radium-Tainted Duplex in Lansdowne.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 20 Sep 1984.

- Stecklow, Steve. “This old house is radioactive.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 17 Mar 1985.

- “EPA Superfund Record of Decision: Lansdowne Radiation, PA.” EPA/ROD/R03-85/014. 2 Aug 1985.

- St. George, Donna. “Lifting the curse of radioactive legacy.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 05 Mar 1987.

- Stecklow, Steve and Mayer, Cynthia. “A $7.5 million housecleaning bill.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 Aug 1988.

- Mayer, Cynthia. “‘Hot House’ is gone, but radiation lingers – and cleanup costs mount.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 9 Dec 1988.

- Gorenstein, Nathan and McGroarty, Cynthia. “Radium: Yesterday’s marvel is today’s mess.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 16 Dec 1991.

- “NPL Site Narrative for Austin Avenue Radiation Site.” Federal Register: 57 Fed. Reg. 46949 (Oct. 14, 1992).

- “Success in Brief: EPA Completes Cleanup of Nation’s Only Residential Superfund Site.” Superfund at Work, EPA 520-F-92-016, Fall 1992.

- “EPA Superfund REcord of Decision: Austin Avenue Radiation Site.” EPA/ROD/R03-94/181. 27 Jun 1994.

- “EPA Superfund Record of Decision: Austin Avenue Radiation Site.” EPA/ROD/R03-96/238. 27 Sep 1996.

- Rubenau, Joel O. and Landa, Edward R. Radium City. Pittsburgh, Heinz History Center, 2019. https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/magazine/Radium-City.pdf. Accessed 4/29/2020.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: