Death from Above by Chocolate

sometimes a story seems too good to be true because it is

Otto Y. Schnering was flying high.

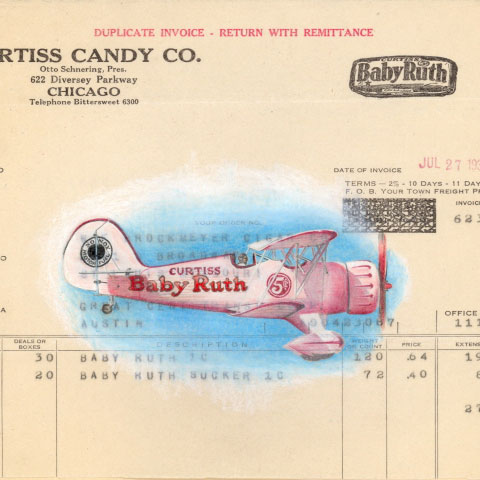

Schnering founded the Curtiss Candy Company in 1916 and had modest success selling chocolate all over the greater Chicagoland area. One of his best sellers was the Kandy Kake, a circular nougat patty topped with nuts and enrobed in chocolate.

In 1921, Schnering noticed the rising popularity of candy bars and decided to bring a cheap 5¢ bar to market to undercut his competitors. He refashioned the Kandy Kake into something you might find a bit more familiar — the “Baby Ruth.” It was the right move at the right time. Soon the Baby Ruth was the best-selling candy bar in Chicago, but Schnering wasn’t content. He wanted to take his company national.

Schnering was a great believer in the power of advertising. If something had caught the public’s fancy, Schnering would make sure the Baby Ruth name was all over it — or at least prominently displayed nearby. Over the years he’d put the Baby Ruth name on race horses, race cars, speedboats, sports teams, you name it.

In 1923, the public’s fancy had settled on airplanes. Powered flight was still new and exciting, a circus attraction that gathered crowds to see wing-walkers, daredevils and aerobats. So Schnering went to Atlanta and hired Doug Davis, one of the era’s most famous barnstorming pilots, to pull off the most audacious publicity stunt ever conceived.

Davis hauled his stunt plane up to the booming metropolis of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, loaded it up with Baby Ruth candy bars, and… well, why don’t I just read it to you straight from history, eh?

Within five minutes, Pittsburgh was a screaming pandemonium. Doug Davis was roaring through the business district, a dozen feet above the streets, looping, rolling and swooping between buildings. Upper-floor office workers experienced the sensation of hearing a roar; glancing out the window, they saw a flying machine a few feet away.

People rushed to the streets and rooftops. Children ran out of schools, drivers left cards standing at intersections. Traffic was jammed for blocks and blocks.

When he was absolutely certain that he had Pittsburgh’s attention, Mr. Davis did what he’d been hired to do. He climbed to the proper altitude and dumped his cargo overboard. Down upon Pittsburgh rained hundreds of tiny parachutes — each carrying a five-cent Baby Ruth bar. The pandemonium was doubled. People risked falls from windows reaching for the parachutes.

Children ran out into the streets (without danger — traffic was hopelessly snarled) and adults fought for free candy.

After a couple of hours, when Davis had run low on gas and had run out of Baby Ruths, Pittsburgh was restored to some sort of order. It was at once obvious to the city fathers that, unless something was done quickly, Pittsburgh would be in constant turmoil, free candy or no free candy. The city council met in emergency session and passed an ordinance prohibiting airplane flights over the city and below a height of several hundred feet, and making candy bars on parachutes illegal.

Man, that’s a great story, isn’t it? It’s almost too good to be true.

Did I say almost? My bad.

It is actually too good to be true.

Things Fall Apart

When I first encountered this story, I wanted it to be true. And why wouldn’t I? But I also wanted more information. And when as I went digging, I immediately noticed one thing: most stories quoted one or more paragraph of that long excerpt I just read, verbatim. The stories that didn’t were usually citing a story that did. And none of the stories said where the text came from in the fist place.

But I was persistent. And eventually, I found one story that credited the original source: a promotional pamphlet published by the Curtiss Candy Company in the mid-1950s.

Marketing is not particularly known for its academic rigor or for having a strict relationship with the truth. This meant that every published reference I had found so far was dependent on a single, unsourced publication. That’s a problem.

But not an insurmountable one. It just meant I’d have to do some more digging. Fortunately, the story gives us a few significant details we can use to narrow our search.

Doug Davis

First, we have aviator Doug Davis. Davis turns out to be a real person, a pioneering aviator and stunt pilot known for being the rival to (and later the partner of) Buffalo Bill’s niece Mabel Cody. Davis and Cody were even the founders of the “Baby Ruth Flying Circus,” which fits our story… almost. It turns out the Baby Ruth Flying Circus doesn’t come into existence until several years after 1923. No serious biography of Davis mentions his candy bombing of Pittsburgh, and the few biographies that do mention it are all quoting the Curtiss pamphlet.

Strike one.

Pittsburgh

Well, I also knew where the candy bombing took place: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. That should be an encouraging sign. In the 1920s Pittsburgh is the ninth largest city in the United States, which means an incident of this scale is going to be widely reported in multiple newspapers across the nation. So off to newspapers.com I went.

A quick search for “Baby Ruth Pittsburgh 1923” turned up a big fat pile of nothing. “Doug Davis Pittsburgh 1923” also got nothing. Adding quotation marks didn’t help, and expanding the geographical region to the entire country didn’t help either.

This isn’t to say searching for “Baby Ruth” was fruitless. I got a lot of results… but none of them for the candy bar.

I got the Sultan of Swat, George Herman Ruth. I got movie stars and vaudevillians like Baby Ruth Sullivan and Baby Ruth Roland. I got Grover Cleveland’s daughter Ruth, who died of diphtheria at the age of twelve in 1904. I got so many foundlings and orphans that it quickly became tiresome to read about them all, though I did perk up when one of them was referred to as a “swamp baby.” I got a character in the musical A Trial Honeymoon; a brand of bread; a life-like toy doll; a miniature alligator that lived in a Lancaster, PA department store; and “Baby Ruth, the world’s only roller-skating pony.” (And if you think I didn’t fall down that rabbit hole for a whole evening you don’t know me very well.)

But nothing about the candy bar in 1923, and no mention of a promotional stunt causing widespread panic in a major American city.

Strike two.

1923

Maybe the Curtiss publication had the date wrong. That happens all the time. Our memories aren’t great, and we have a tendency to mentally adjust events to fit better into our life stories. So I thought I’d expand the date range.

Now, I know the story couldn’t possibly have taken place earlier than 1921 because the Baby Ruth candy bar didn’t exist before then. A search for “Baby Ruth” 1921 comes up with nothing. Same with 1922, and I’ve already done 1923.

In 1924 we do start to see results. In March, there’s a national trademark registration for Baby Ruth which mentions Curtiss has been using it as a mark since 1921, which is a good sign. Shortly after that we start to see notices that the brand has been licensed to regional confectioners. The brand name starts popping up in advertisements and want ads.

And then, on November 28, 1924 I find the first real result, a small advertisement.

Look for the Baby Ruth airplane today and Saturday. Catch a parachute and get a bar of Baby Ruth candy.

It should be an encouraging find, proof that the candy bombing did take place. Except that this ad is running in Alabama, in the Montgomery Advertiser. It’s a whole year off, and in the wrong part of the country. So I keep searching. A follow-up article mentions that Davis’s affiliation with Baby Ruth is something new.

After 1924, there are so many references to Baby Ruth candy bombings that I start to lose count. They were definitely a real thing. There are no reports of widespread panic, none of them seem to have taken place over city centers, and all of them appear to have been advertised well in advance. I can’t find any taking place in Pittsburgh, though. The closest I can get is an Altoona air show in 1925, over two years and 100 miles away.

So it’s not looking good.

Foul tip, still strike two.

The Law

But I’ve got one more trick up my sleeve. The original story mentions that after the candy bombing, the Pittsburgh city council passed an ordinance prohibiting airplanes from flying over the city and making candy bars on parachutes illegal.

Pittsburgh’s current municipal code doesn’t have any such prohibitions, but municipal codes change quite a bit over time. So last October I spent an evening in the Allegheny County Law Library, poring through the Municipal Record. I pulled volumes from 1921-1925 and I found nothing. Nothing about candy bars, nothing about airplanes, nothing about advertising. No resolutions, no ordinances.

Nothing.

Strike three. That would seem to be the end of it.

Almost.

So What Really Happened?

I did find something in all my searching that I didn’t tell you about, a short article from the Atlanta Constitution, on December 18, 1924. It’s only four sentences long, so I’ll just read the whole thing for you:

Doug H. Davis, Georgia aviator, who has been distributing samples of candy from an airship over the city, was fined $10 in police court today. This is the first aviator to be arrested here. The arrest was made by a motorcycle officer after Davis landed. It is a violation of a city ordinance to drop anything from an airship in Macon.

Whaddya know. And it’s even right there in the Macon-Bibb County municipal code, §3.10: “It shall be unlawful for any person or persons to drop from any aircraft, pamphlets, papers, noise-producing devices or other things.”

That’s as close as we can get to the legendary Pittsburgh candy bombing run. It happened in a different year, in a different part of the country. It didn’t cause a widespread panic, and it didn’t prompt the city to change its laws but was instead a violation of an existing ordinance.

And it makes sense. Doug Davis was based out of Atlanta and operated mostly in the South. Newspaper articles show that Baby Ruth was aggressively expanding in that part of the country. Why wouldn’t the bombing runs start down there?

So how did the story get changed?

Marketing.

Moving the date from 1923 to 1924 is probably just a matter of poor record-keeping and hazy personal recollections. Moving the location to Pittsburgh, a city with ten times the population of Macon, is just trying to make the story seem more important. And changing a $10 fine into a ripping yarn about people falling out of buildings and panic in the streets is hucksterism, pure and simple.

There you have it. Candy bombings did happen, but this particular one did not. For seventy years, credulous people have been regurgitating marketing copy without bothering to do the legwork to verify it. Which is a shame, because it really was too good to be true.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m going to enjoy myself a Baby Ruth.

Connections

Buffalo Bill Cody had a lot of nieces. Mabel Cody became an aeronaut and helped found the Baby Ruth Flying Circus. Another niece, Sadie Cody, became associated with faith healer and would-be messiah John Alexander Dowie (“Marching to Shibboleth”).

Another legendary story from Pittsburgh is the saga of Joe Magarac, the Paul Bunyan of the Steel industry, which may have been entirely made up by a down-on-his-luck author. (“Jackass Forever”)

Sources

- Almond, Steve. Candy Freak. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2004.

- Broekel, Ray. The Chocolate Chronicles. Des Moines: Wallace-Homestead, 1985.

- Broekel, Ray. The Great American Candy Bar Book. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1982

- Chmelik, Samantha. “Otto Y. Schnering.” Immigrant Entrepreneurship. https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entry.php?rec=111 Accessed 9/5/2019.

- Cobb, Kyl. Griffin: Georgia: We Could Have Been Famous… Volume 2: Heroes, 1890-1949. Self-published, 2016.

- “Curtiss Candy Co., est. 1916.” Made in Chicago Museum. https://www.madeinchicagomuseum.com/single-post/curtiss-candy-co Accessed 9/1/2019.

- “Doug Davis (aviator).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doug_Davis_(aviator) Accessed 9/1/2019.

- “Macon-Bibb County, GA Municipal Code.” Municode. https://library.municode.com/ga/macon-bibb_county/codes/code_of_ordinances Accessed 2/11/2020.

- Municipal Record: Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council of the City of Pittsburgh for the Year 1921. Pittsburgh: Kaufman Printing, 1922.

- Municipal Record: Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council of the City of Pittsburgh for the Year 1922. Pittsburgh: Kaufman Printing, 1923.

- Municipal Record: Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council of the City of Pittsburgh for the Year 1923. Pittsburgh: Kaufman Printing, 1924.

- Municipal Record: Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council of the City of Pittsburgh for the Year 1924. Pittsburgh: Kaufman Printing, 1925.

- Municipal Record: Minutes of the Proceedings of the Council of the City of Pittsburgh for the Year 1925. Pittsburgh: Kaufman Printing, 1926.

- Official Gazette of the United States Patent Office, 18 Mar 1924.

- Stebbins, Clair C. “Doug H. Davis.” Aviation Quarterly, Vol 9. No. 2 (Spring 1990).

- Wells, Jeff. “The Day Baby Ruths Rained Down on Pittsburgh.” Mental Floss. https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/70002/day-baby-ruths-rained-down-pittsburgh Accessed 8/28/2019.

- Advertisement. Montgomery Advertiser, 28 Nov 1924.

- “Sugar-coated shells fall and all Atlanta Surrenders.” Atlanta Constitution, 10 Dec 1924.

- “Aviator drops candy from air in Macon, Draws fine of $10.” Atlanta Constitution, 18 Dec 1924.

- “Pilot of airplane bombards city with candy parachutes.” Tampa Tribune, 21 Jan 1925.

- “Candy will rain from sky tomorrow.” Greenwood Daily Commonwealth, 10 Mar 1925.

- “Candy to be given.” Montgomery Advertiser, 15 Jul 1925.

- “Candy dropped from airplane.” The Messenger (Owensboro, KY), 24 Sep 1925.

- “Baby Ruth plane is gone.” The Messenger (Madisonville, KY), 26 Sep 1925.

- “Displays at fair big drawing card on opening day.” Altoona Tribune, 20 Aug 1925.

Special Thanks

This episode would not have been possible without the assistance of Lori Hagen, senior research assistant at the Allegheny County Law Library. Thanks, Lori, you’re the best.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: