French Leave

a baseball superstar, an irate owner, and a clever workaround

(A quick note: the recorded episode features snippets of an interview we conducted with #23 about the particulars of this case. In this transcript, those sections are represented by the green backgrounds.)

It was time.

The National League had been the dominant force in baseball ever since it was formed in 1876. Sure, there were rival leagues from time to time — the American Association, the Union Association, the Player’s League — but the National League defeated them all with a deft combination of superior play, clever marketing, and underhanded business practices.

The 1900 season had not been a good one for the National League. Attendance was down. Way down. So at the end of the year, the league announced that it would drop four of its twelve teams.

Ban Johnson, president of the minor-league Western League, saw an opening. He saw that fans weren’t bored with baseball, they were bored with the National League. In 1901 he renamed the Western League to the snappier “American League,” started teams in three of the cities abandoned by the National League, and added other new teams to directly compete with existing National League franchises.

Most importantly, the new league refused to re-sign the National Agreement, the anti-competitive compact signed by all the minor leagues forcing them to abide by National League contracts. Since those contracts included a “reserve clause” preventing players from negotiating with other teams, and an “option clause” allowing the team to renew contracts at will, players were essentially bound to the same team for life.

Now what can you tell us about the reserve and option clauses?

The reserve clause primarily is a device used by the owners to create stability in their organization, especially when you have a professional sports league. Basically, it is a clause whereby the owners could designate a certain number of players as indispensable players that other teams could not negotiate with and basically lock that player into playing for the team he was with if he was designated as one of those indispensable players.

Now that’s the reserve clause. But the unique thing about the reserve clause in this case is that teams had a right to designate five players at one point. Then they had increased that to eleven players, and that’s significant because there were only fourteen players on a team. So the whole team was designated…

Everybody except the ball boy, I’m assuming.

So, basically they were trying to prevent exactly what happened. Raids on their team, other people coming in and offering to pay a bit more money and getting them.

Now, the option clause was a little different. The option clause was that the team had a right to exercise an option in the contract to say, “Look, we’re gonna bind you to another two or three years of work for us.” That could only be done by exercising this option to play for two or three more years. But there was no corresponding right of the player to say, “No, I can play for somebody else.” What it boiled down to was this: He either had to take it or leave it.

And the team also had the other side of it. They could say, “Look, we don’t want you to play for us any more,” give you ten days notice and begone with you. So the gist of this option clause was that these teams could lock in the players for three years by exercising the option, yet kick them out in ten days if they didn’t want them around any more. Hardly a fair deal.

To top it off, the National League also unilaterally imposed a $2,400 salary cap on all players in 1894, well below the market value of their services. Many NL owners found ways to pay superstars under the table, but they were never very generous. Why would they be? They were the only game in town.

When the American League dropped out of the National Agreement, they simultaneously launched a massive talent raid on the National League clubs. Ultimately, they signed away some of the best players in the National League like “Iron Man” Joe McGinty, “Turkey Mike” Donlin, Roger Bresnahan, Chick Stahl, Jimmy Collins, John McGraw, and some guy you may have heard of named “Cy Young.”

Indignant National League owners fought back in court, led by their legal counsel, Colonel John Ignatius Rogers, owner of the Philadelphia Phillies.

Rogers’ Phillies were a prime target for the talent raids, probably because Rogers himself was not well-loved. John Schiffert’s Baseball in Philadelphia memorably describes him as “self-promoting, stubborn, arrogant, overbearing, enraged, gloating, litigious, bitter, mean-spirited, long-winded, meddler, suspicious, strident, and manipulative.”

Schiffert could have also added “cheap.” Rogers was the chief architect of the National League’s reserve clause and the salary cap, and seemed to delight in keeping player salaries as low as possible. When given a chance to get out from under Rogers’ thumb, players took it willingly. When the dust cleared, the Phillies had lost four key players: pitchers “Frosty Bill” Duggleby, “Strawberry Bill” Bernhard and “Chick” Fraser; and second baseman Napoleon Lajoie.

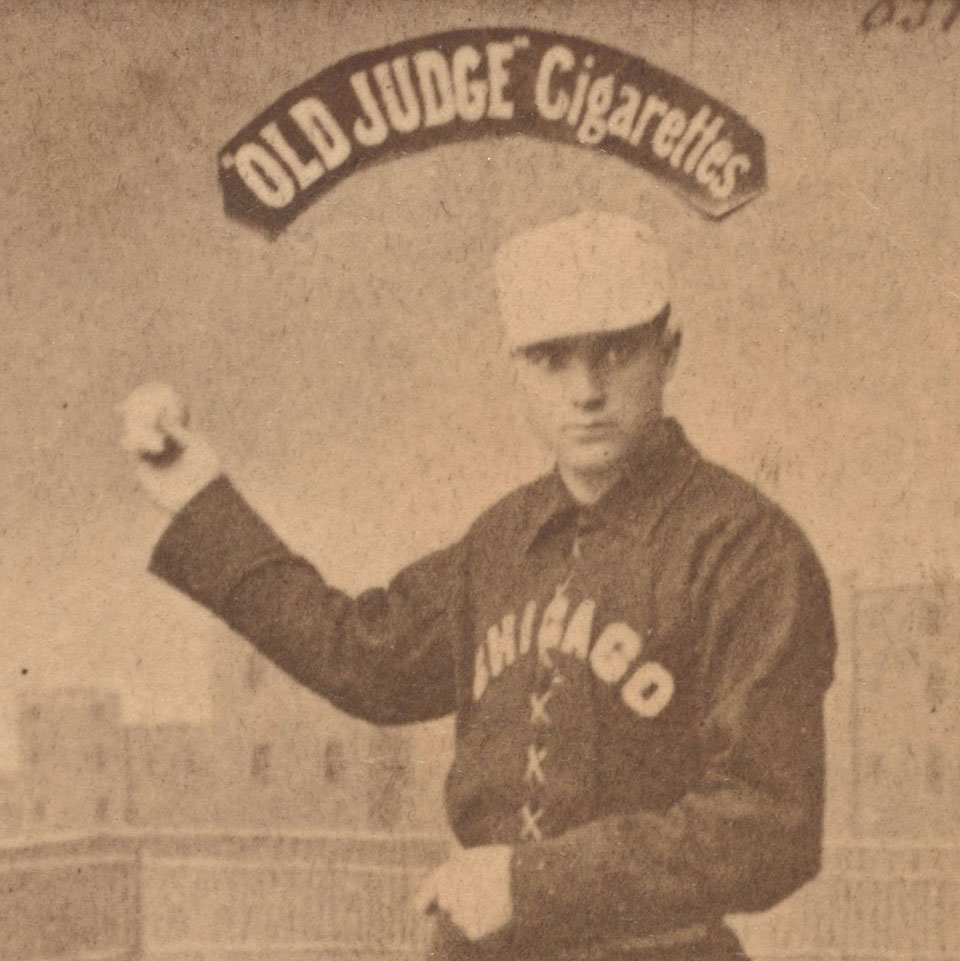

Lajoie, nicknamed “Nap” or “Larry” or sometimes just “Frenchie,” was the real steal. These days, we tend to forget how good Nap was, but here’s all you need to know: he was the sixth player admitted to the Baseball Hall of Fame. When the only strike against you is that maybe you’re not quite as good as Ty Cobb or Babe Ruth, you’re in some pretty rarefied company. In 1901 Lajoie was till an up-and-coming star. He’d had five amazing seasons, hitting over .320 in each, batting in more than 100 runs twice, and stealing more than 20 bases thrice.

No matter how cheap he was, Rogers knew he had to keep a player like that happy and he slipped Nap $200 under the table in 1900. But then Nap found out that Rogers had been slipping team captain Ed Delahanty, who had similar stats, $600. In 1901 he refused to sign his contract extension unless Rogers made up the $400 difference for the previous year.

So when Ben Shibe and Connie Mack of the newly-formed Philadlephia Athletics offered Lajoie a multi-year contract worth $4000/year, Lajoie switched clubs without hesitation. (Supposedly, Rogers offered to match the Athletics’ contract, and Lajoie was ready to agree — but only if he got the $400 he felt he was owed for 1900. Rogers refused, and Lajoie left.)

Round 1

Rogers wasn’t going to take it lying down, though. In March 1901 he went to the Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas and filed for an injunction to prevent Lajoie from playing for the Athletics.

Rogers, who had drafted the reserve and option clauses himself, was absolutely convinced that they were ironclad. The Athletics were equally convinced that they were completely unenforceable. Both sides relished a chance to prove their arguments in court.

Rogers, having drafted the clauses, is obviously convinced that they’re great because he’s a giant egomaniac who think he can do no wrong. Why would the American league think these clauses were unenforceable?

Let’s go back to Rogers himself. First off, we’re dealing with contract law. Written documents. And there’s been contract law in existence for two to three hundred years, from the English common law. A basic contract requires an offer, acceptance, consideration, burdens on both sides, a meeting of the minds, intent to be bound by the contract, and certainty of terms.

The reason contracts were deemed inviolate — your word is your bond, your written word is your badge of honor, so to speak, you live up to you word — so what was written and signed was considered inviolate.

So that’s one of the reasons why, I suppose, that Rogers thought he was invincible and walk into because one, Nap signed the contract. He agreed to all the stuff he now disagreed with him. The contract was clear and unambiguous as written by Rogers. Everybody knew what was going on. The ten day clause was in there, the reserve clause was in there. Whether Lajoie understood it, we don’t know, but he signed it anyhow.

Rogers also felt he could prove irreparable harm if the contract wasn’t enforced, which is that the Phillies would lose a lot of money because Nap wasn’t going to play for them. And that was a big deal because Lajoie was a very very big draw. When he did go play for the A’s, the A’s got 10,500 people to see him on the first day. The Phillies only had 750 or so.

Then, also, Rogers thought, “Hey, the A’s are stealing my players and I’m not getting any money from them. So I’m losing all the way around, and this wasn’t right. Somehow or other I have to have some way, some remedy available to me so I can have this contract enforced.” And the only way he could go into court and do that was to request for an injunction.

We talked about the reserve clause and the option clause. But we didn’t talk about specific performance. “Here’s the contract, I’m going to pay you $2,400, you have to play for the Phillies.” The contract also had a clause for specific performance, which is that Lajoie agreed to that remedy in court. If there was a violation of contract, the Phillies could go into court and order him to specifically play for the Phillies. Lajoie signed that too.

And that’s why Rogers was so firm that he thought he would prevail, that it was ironclad, and that he couldn’t lose.

Why the American League thought it was objectionable and they thought they would win was basically the fairness side of the argument. The contract was one-sided. It was either play, or not play and he could dictate all the terms and that wasn’t fair. And it was an unconscionable deal. He was basically bound to life to the Phillies, where the Phillies could just cut him adrift in ten days.

Those arguments have always been present in the law, especially the written law, when one side has more power than the other in a bargaining agreement. So that’s basically the forces that were set up for resolution by the court.

The case went before a judge in early April.

First, the Athletics went after the contract on technicalities. Lajoie had apparently signed his original contract in pencil, not pen. He had never received a personal copy of the contract. And the option had only been signed by one of the club’s managers, but was supposed to have been signed by two. These might seem like picayune objections to you, but they’re good lawyering — throw out every argument you can think of, in the hope that one of them sticks.

The rest of the arguments went mostly as expected. The Athletics argued that the reserve and option clauses were onerous and one-sided. The Phillies argued that they were entirely fair, and had been standard boilerplate in league contracts for years, as if that somehow made them enforceable.

There was at least one moment of levity in the courtroom. While arguing against reserve clauses, which were usually reserved for indispensable experts whose loss would lead to irreparable harm, Athletics’ lawyers managed to get Phillies manager William Shettsline to begrudgingly admit that he considered every man on the team an expert. With the exception of third base coach Pearce Chiles, who had been demoted from outfielder to third base coach and then fired after getting caught stealing signs.

After a few weeks, a ruling came in. Writing for the panel, Judge Ralston wrote:

It was stated at the argument that the base ball clubs have found it necessary to reserve the right to discharge; that without it the business must be discontinued. This may be so, but if the clause is so important that it cannot be omitted, then the benefits arising from it must compensate for the lack of the remedy by injunction, for a court of equity will not enforce specific performance of a contract, or enjoin the breach of it, where one party is bound for a series of years while the other may annul it at any time upon giving ten days notice.

If the court were to enjoin the defendant for the balance of the period for which he agreed to play for the plaintiff there would be no way to compel the plaintiff to employ him or pay him a salary for more than ten days.

Such a contract is lacking in mutuality, and a court of equity will leave the parties to their remedies at law.

The injunction is refused and the bill dismissed.

Judge Ralston’s decision here seems to hinge on mutuality of contract. Can you briefly describe the principle of mutuality.

Mutuality is a very confusing concept because sometimes it gets broken down into two other concepts. But it begins with the idea that there’s equality of burdens to a certain extent.

But they break it down even further, and that’s where it gets confusing. You can have mutuality of obligation — it’s a fair deal all the around, you’ll play baseball for me, I’ll pay you $2,400. That seems like a fairly simple easy deal. Mutual burden.

That’s the burden. The remedy, what can somebody do for you, what are your rights to compensation or relief if the contract is breached? Well the remedies were a little different.

So mutuality of obligation is one thing, mutuality of remedy is other, and that’s when people get confused, when those two terms are intertwined. And it’s almost impossible to get them un-intertwined, if you know what I mean. Because the remedy in this case was the Phillies could keep him on for three years just by exercising the option.

Lajoie had no other right or remedy. He could get kicked out in ten days or his contract could be terminated in ten days. But he had no similar right against the Phillies to say “You must pay me for three years.” No.

To a certain extent that makes some sense in terms of professional sports. As we all know people get hurt, they lose their skills, they lose their abilities…

Sham retirements…

True! But the mutuality of what the court considered in this case was the ten day clause where Nap could be let go after ten days notice. They thought that wasn’t a fair deal. They thought the remedy wasn’t mutual, therefore they struck the whole contract as void for lack of mutuality of remedy, not mutuality of obligation.

Rogers, of course, railed against the decision, arguing that a contract enforceable in a court of law should not have specific enforcement in a court of equity. But for now, the case was settled. The Athletics had won.

The split between law and equity. Law… if you’re in a contract of law. Say you enter into a contract, I’ll pay you a dollar a horseshoe for 500 horseshoes and you deliver me 500 horseshoes. Simple deal, it’s a simple contract, it’s a legal and it’s enforceable in a court of law, okay? But only enforceable to the extent that we’ll pay you money if you breach the contract. One side will have to pay the other side money if the contract is breached.

Pragmatically speaking, you know and we all know that there are other things that are involved in a breach of contract that don’t involve money, or can’t be solved by payment of money. So if he signs a contract to play for the Phillies and now he’s paying for someone else, no amount of money is going to bring him back if he doesn’t want to play.

Nap doesn’t have enough money to pay the Phillies for all their loss of profit in any given year…

And for that matter, how much could you prove that profit was due to Nap? Certainly there are other factors as well.

There are thirteen other members of the team. Exactly. Bottom line is, you then go to the consideration of the equity side of the court.

A court also has two hats. One hat is the law side, the other hat is the equity side. And the equity side is the fairness, the reasonableness, you can’t do contracts against public police, you have to be reasonable. Those sort of considerations. But specifically when it comes to ordering things other than money.

In this case, they wanted specific performance. The Phillies went into court to require Lajoie to play for the Phillies, or to stop him from playing from the Philadelphia Athletics or any other team. That doesn’t involve money. That involves prohibition or enjoining, they call it enjoining certain conduct.

And that’s the fairness side of the courts. The fairness side, the equitable side, which involves something more than basic contract analysis.

Meanwhile, Nap Lajoie had the season of his life. He led the league in eight offensive categories: batting average (.422), slugging (.643), hits (232), total bases (350), doubles (48), home runs (14), runs scored (145), and RBIs (125). But even though their star won the triple crown, the Athletics finished in fourth place.

The Phillies had to make do with Bill Hallman at second. Hallman hit a pathetic .184, far below the Mendoza Line (though to be fair, Mario Mendoza wouldn’t even be born for another 49 years). Somehow, they still managed to finish second, 7.5 games behind the first-place Pittsburgh Pirates.

Round 2

Rogers and the Phillies appealed the Court of Common Pleas ruling to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. Arguments were made before the court in mid-November, though the judges took their time thinking over the merits of the case.

In the meantime, the National League established a “corruption fund” to try and lure American League players back into the fold. The New York Giants offered Nap a three-year contract worth $7,000/year, which Lajoie politely declined.

The Supreme Court’s ruling did not come down until April 22, 1902, almost a month into the season. It was a stunning reversal:

The legal principle that contracts must be mutual does not mean that in every case each party must have the same remedy for a breach as the other… Mere difference in the rights stipulated for does not destroy mutuality of remedy. Freedom of contract covers a wide range of obligation and duty as between the parties and it may not be impaired, so long as the bounds of reasonableness and fairness are not transgressed.

My understanding as I’m reading this is that the Supreme Court considered the mutuality of remedy here a Hobson’s choice. Lajoie could either take it or leave it. That was his mutuality of remedy, sign or not sign.

That was part of it. But yet they also noted he wasn’t getting nothing, he was getting $2400 if he signed the contract. Yes, there was a reserve clause in it. And the court basically said, “He could have objected.”

Now where that would have got him, I don’t know, but the court said he could have objected to that provision of the contract. Whether the Phillies would have taken that out, I don’t know. But he signed, and again we come back to that your contract is inviolate, your written word is your bind so to speak.

So their basic consideration here is that because Lajoie has the option of not playing baseball at all, the contract is still mutual.

Uh, I’m going to say this. This is not the finest hour of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court.

I tried reading the ruling and it seemed like some pretty dense legalese. So it was hard to read and even harder for a layman to understand. Did you find it similar?

Yes I do. Even the modern commentators who try to analyze it have some difficulty in boiling it down to its essence. But the bottom line, they say, “You sign the contract, you’re bound by it.”

A telegram with news of the injunction was sent to the Athletics, and arrived during a game against the Baltimore Orioles. When Connie Mack read it, he pulled Lajoie from the lineup in the middle of the eighth inning. Nap would not play for weeks while American League lawyers debated how to proceed. Rogers gloated to the press that Nap would be back under his thumb any day now. So he was surprised when in early June, Lajoie was traded from the Athletics to the Cleveland Bronchos.

The American League had public opinion and precent on their side. Pennsylvania was the only state that ruled in the National League’s favor in these contract disputes: courts in Missouri, New York, and Washington, DC had all ruled for the American League. (In fact, the Missouri court found specifically called out the Pennsylvania decision, calling it “inequitable, unconscionable, and contrary to public policy.”)

Based on that, American League lawyers ultimately decided that the Supreme Court’s injunction would not be enforceable outside the state of Pennsylvania.

Now, why would it be unenforceable outside of Pennsylvania? Obviously, we have intra-state contracts signed all the time. Criminal law obviously has special things where if you flee across state lines there are federal organizations to enforce that. But why would contract enforcement not be possible across state lines?

Well, “full faith and credit” may apply to certain types of orders of the Supreme Court of one state, but when there is lack of jurisdiction…

Remember now, this is a Philadelphia case. It started out in the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas and eventually made its way to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. And at the time Lajoie was in Philadelphia, and the Philadelphia Phillies were in Philadelphia, and the Philadelphia A’s were in Philadelphia. So everything was concentrated in Philadelphia. Hence it was easy for a Philadelphia court to say, “We’re going to void the contract.” The bottom line is all the parties were in Pennsylvania.

When you go to another court, another state, and the parties, maybe one party isn’t a resident of that other state. They call it in personum jurisdiction. If all the parties aren’t there sometimes the court doesn’t believe they have the power or right to enter any orders that affect those other people.

Connie Mack traded Lajoie to Bronchos, partly as a favor to their owner (a personal friend), and partly as a favor to the league (which was trying to bolster attendance for the struggling Cleveland franchise). And it worked. Lajoie couldn’t carry the whole Cleveland team on his back, but he could lift it back to the middle of the standings with his league-leading .378 batting average.

Rogers was furious. He had Lajoie declared in contempt of court and tried to serve injunctions against him, but Pennsylvania sheriffs returned the injunctions endorsed non est inventus — the enjoined could not be found. But the injunctions did mean that Nap Lajoie was a wanted man in the state of Pennsylvania.

Since he risked arrest by setting foot in Pennsylvania, Lajoie made separate travel arrangements that allowed him to avoid the Keystone State entirely. When the Bronchos had to play the Athletics in Philadelphia, he’d chill in Atlantic City for a few days and then rejoin the team afterward. For 1902, that’s superstar treatment. Manager Bill Armour jokingly called the situation “French leave.”

Since he couldn’t lay a finger on Lajoie in Pennsylvania, Rogers filed for an injunction in the Ohio Court of Common Pleas. But Judge Wing dismissed the suit in August, on the rather technical grounds that it had no jurisdiction to enforce Pennsylvania laws on a resident of Vermont.

The actual ruling was that the Ohio court was not compelled to enforce a decree for specific performance of a Pennsylvania contract. They didn’t actually disagree with the ruling, and they sort of gave it lip service and said, “That’s a nice decision but we’re not going to enforce it because it calls for specific performance of a contract made in Pennsylvania, here were are in Ohio, we’re not going to do that.”

How much of that was because the judges were in the pocket of the Cleveland Indians, we’ll never know, will we?

Rogers was fit to be tied. But this time there was nothing the Colonel could do.

Fugitive No More

In the off-season, the rival leagues buried the hatchet and signed a new National Agreement. The reserve and option clauses that had been decried as monstrous and inequitable soon became standard in American League’s contracts. As part of the “peace treaty” the teams allowed players who’d jumped to stay where they’d landed. In the cases where a player had conflicting contracts, an arbitration committee would determine which team had the better claim.

One owner who wasn’t happy about all of this was Colonel John I. Rogers, who argued that the league did not have the legal authority to sign away his contractual rights. Unfortunately for Rogers, the Phillies had seen declining attendance and were losing money hand over fist. He was pressured to sell the team to another management group and was out of baseball. (Thank God.)

One player who still had a problem was Nap Lajoie, who remained a wanted man in Pennsylvania. In May 1903, the Athletics, Bronchos and Phillies all filed an injunction for relief in advance of a Bluebirds/Athletics series in early June.

Amazingly, the petition wound up on the docket of Judge Ralston, who had handed down the original ruling in Lajoie’s favor. Ralston apparently thought that all of the parties in the original suit had been acting abominably, and deserved every punishment that had come their way. But in the interests of peace, he set the injunction aside. But he did wait until the last second to issue his ruling.

Nap Lajoie was a free man once again. He would continue to play and manage for Cleveland until 1914, and was so beloved in that they even renamed the team the “Cleveland Naps” in his honor. He played one more season for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1915, spent a few years in the minors, and then retired. In 1937 he was elected to the second class of the Baseball Hall of Fame.

John Rogers had been forced to sell his interest in the Phillies, but he’d retained ownership of their ballpark. Unfortunately, the notoriously cheap Rogers didn’t keep up on maintenance. A balcony collapse in August 1903, killed twelve and injured hundreds. The resulting lawsuits ruined him.

Major League players would continue to be indefinitely bound by the reserve and option clauses until Curt Flood and Marvin Miller established free agency in 1972.

Would you say the Pennsylvania’ Supreme Court’s ruling had any influence on sports law going forward?

Well, strangely, and even though a bunch of other courts have refused to abide it, it does have some ongoing significance in terms of basic contract law. Let’s set this up a little bit.

You have decision issued by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, which is the highest court of one state. And we all know there’s a hierarchy of laws. It goes from the lower courts to the trial courts to the superior court, intermediate state… the law of any given state is whatever the supreme court says it is.

But here you’ve got rinky-dink courts in Missouri saying this contract, the same contract that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court looked at in essence, was inequitable, unconscionable, contrary to public policy, violated anti-trust provisions, deprived players of due process, and even one said constituted involuntary servitude! Which… I can see that. It’s a little stretch.

To find a civil rights claim in a baseball law argument is strange.

Another interesting facet of this is this guy Rogers, who must have had immense hubris, went into federal court in Philadelphia a month after the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania’s decision. One month later he went into federal court, but not in a Phillies case. It was a case where he was suing on behalf of the Brooklyn baseball club. It was a Brooklyn case. All the parties were in New York but he filed this case in the federal court in Philadelphia. And the federal court in Philadelphia completely rejected the argument of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania and said that this was not a unique contract, it was an unfair and inequitable contract, and that the injunction should not have been granted, at least for the Brooklyn team.

Now we’ve got a case where multiple courts are arrayed against the Pennsylvania Supreme Court on this issue. But yet over time the notion of mutuality of contract and its ruling on mutuality of contract has actually taken hold. Because it’s the highest court of a state. When other states start looking at decisions for precedential value and to support it, they don’t go looking for the Court of Common Pleas of Cuyahoga County or some local low court in Missouri. They look for the highest decision of any given state. And so the Pennsylvania Supreme Court is given some credence among legal scholars.

And in this case the mutuality of contract determination of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court has given significance that the ten day provision does not in and of itself render a contract void for lack of mutuality.

Even though at the contemporary time that argument was rejected by almost every other state court and federal court that heard the case, years of time have stripped out the context so the ruling itself is seen out of context and still has precedential value, essentially.

That’s correct. Very succinct synopsis.

Connections

It’s a tenuous connection, but a connection nonetheless! The Philadelphia Athletics eventually moved west to become the Kansas City Athletics, and then even further west to become the Oakland Athletics. The Oakland A’s employed baseball’s only designated runner, “Hurricane” Herb Washington (“Hurricane Coming Through”).

Lajoie chose to jump to the American League in 1901 because of the discrepancy between his pay and that of team captain Ed Delahanty. The following year, Delahanty himself would leap to the American League — and the year after that, he would be dead (“Triple Jumper”).

The famously parsimonious Colonel John Ignatius Rogers has shown up in an improbable number of episodes including “Triple Jumper” (about the mysterious death of Ed Delahanty), “The Buzzer Brigade” (where he used electronics to cheat at baseball), “520%” (about a con man); and “A Month of Billys” (about preacher Billy Sunday’s baseball career).

Sources

- “1902 Cleveland Bronchos: Schedule.” Baseball Reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/CLE/1902-schedule-scores.shtml Accessed 5/11/2020

- “1902 Philadelphia Athletics: Schedule.” Baseball Reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PHA/1902-schedule-scores.shtml Accessed 5/11/2020.

- “1903 Cleveland Naps: Schedule.” Baseball Reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/CLE/1903-schedule-scores.shtml Accessed 5/1/2020.

- “Ed Delahanty.” Baseball Reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/d/delahed01.shtml Accessed 5/11/2020

- “Nap Lajoie.” Baseball Reference. https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/l/lajoina01.shtml Accessed 5/11/2020.

- “John Rogers (baseball).” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Rogers_(baseball) Accessed 5/1/2020.

- “Nap LaJoie.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nap_Lajoie Accessed 5/1/2020.

- “Base ball surprises: If affairs are as stated, the Phillies will be losers.” Altoona Tribune, 9 Feb 1901.

- “Lajoie not signed.” Philadelphia Times, 10 Feb 1901.

- “Was it fairy tale” Allentown Leader, 15 Feb 1901.

- “Waiting to Fight.” Allentown Leader, 14 Mar 1901.

- “The Old Sport’s musings.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 Mar 1901.

- “National League opens the fight.” Philadelphia Times, 27 Mar 1901.

- “Ha! Ha! the legal dogs of war are slipped by angry Colonel Rogers.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 Mar 1901.

- “League victory in law would mean defeat on field.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 Mar 1901.

- “Base ball suits filed in equity.” Philadelphia Times, 29 Mar 1901.

- “American League people promptly call bluff of Philadelphia club.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 30 Mar 1901.

- “Col. Rogers Files an Amendment to Bill in Equity.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 Apr 1901.

- “Lajoie gets back at the Colonel and tells a few things on his own account.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 20 Apr 1901.

- “Lajoie scores first in big fight to restrain him from playing for Mack.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 21 Apr 1901.

- “Lajoie is freed from National League yoke and ten-day clause knocked out.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 May 1901.

- “John I. Rogers on Lajoie case.” Philadelphia Times, 23 May 1901.

- “Comment.” Philadelphia Times, 16 Nov 1901.

- “Comment.” Philadelphia Times, 17 Nov 1901.

- Philadelphia Ball Club, Ltd. v. Lajoie, 202 Pa. 210, Pa. Supreme Court (1902)

- “Decision in Lajoie’s case is reversed.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 Apr 1902.

- “American League will fight case.” Philadelphia Times, 22 Apr 1902.

- “Lajoie enjoined for five days.” Philadelphia Times, 24 Apr 1902.

- “Injunctions are made permanent.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 Apr 1902.

- “Americans win over Nationals out in St. Louis.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 7 May 1902.

- “League contract really perpetual.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 14 May 1902.

- “Lajoie and Bernhard go to Cleveland.” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 24 1902.

- “No legal move in Lajoie case.” Philadelphia Times, 9 Jun 1902.

- “Notice served on two jumpers of court’s rule.” Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, 13 Jun 1902.

- “Non est inventus.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 Jun 1902.

- “Base ball pot begins to boil.” Philadelphia Times, 30 Jun 1902.

- “Cleveland judge dismisses suit.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 10 Jul 1902.

- “Jumpers barred from this state.” Pittsburgh Press, 13 Jan 1903.

- “National peace committee lacked power to sign away Phillies’ enjoined players.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 Jan 1903.

- “Lajoie forgot law.” Pittsburgh Press, 22 Feb 1903.

- “Not eligible to promenade here.” Pittsburgh Press, 6 Jun 1903.

- “Nap Lajoie is pulled up.” Pittsburgh Daily Post, 22 Apr 1902.

- “Will play in Phila.” Buffalo Times, 06 Jun 1903.

- “Exiles may play in to-day’s game.” Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 Jun 1903.

- “Napoleon Lajoie: How Major League Baseball Made Legal History.” State Museum of Pennsylvania. http://statemuseumpa.org/napoleon-lajoie-war-between-american-national-leagues/ Accessed 2/1/2020.

- Rogers, C. Paul III. “Napoleon Lajoie, Breach of Contract and the Great Baseball War”, 55 SMU L. Rev. 323 (2002)

- Schiffert, John. Baseball in Philadelphia: A History of the Early Game, 1831-1900. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006.

Links

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: