The Realest Housewife of Beverly Hills

confidante of kings, movie stars, and mobsters

Dorothy Cadwell Taylor was born in Watertown, New York on November 13, 1888.

Her father, Bertrand Leroy Taylor, was a leather goods manufacturer who turned a small fortune into a large fortune by playing the market. His children were raised ub the lap of luxury — no, more than that, a lap that grew more luxurious by the day. They were given the best education, wore only the finest clothes, and lived in a mansion on Fifth Avenue just across the street from Central Park.

As a teenage debutante Dorothy was known for her “piquant prettiness”: she had silky black hair; a shapely head; big, black-lashed blue-gray eyes; and a figure “so perfect that she wears no corsets under her smartest gowns.” Her vivaciousness and quick wit made her a hit at parties. She was also good at sports: she was a strong swimmer, an excellent golfer, and a good doubles partner for tennis.

Later, she was known for… other things.

Here’s an example. In November 1904 the Taylors’ car was pulled over for careening down Fifth Avenue at forty miles an hour, veering wildly from lane to lane. The cops began grilling the family chauffeur, but fifteen-year-old Dorothy pushed him out of the way and declared that she had been behind the wheel and just wanted to how fast the car could go. She knew she didn’t have a driver’s license yet, so she figured there was some sort of small fine she’d have to pay and began reaching for her pocketbook. The cops arrested her instead. During her arraignment Dorothy was openly contemptuous of the court, and in the end her father wrote a check that made all of this all go away.

This is Dorothy Taylor in a nutshell. From one point of view she was merry and mischievous, filled with joie de vivre, honest and brave and unafraid to face the consequences of her actions. From another point of view she was reckless and impulsive, indifferent to the problems she was creating for everyone else, and only willing to face the consequences of her actions because she was sure that her money and social status would shield her from the worst of them.

In 1910 Dorothy was engaged to James Ralph Bloomer, a stockbroker from Cincinnati. They picked a wedding date in October, and then Dorothy abandoned her new fiancé to go on a summer vacation in Europe with her parents. Absence did not make the heart grow fonder; she soured on Bloomer, and Bloomer soured on her. The engagement was finally broken when the Taylors returned from Europe… several weeks after the proposed wedding date.

One of the souvenirs Dorothy brought back from Europe was a French bulldog named Toto which she had purchased in Paris. It should not surprise you to learn that she was a terrible dog owner who treated Toto more like a fashion accessory than a pet and made no effort to train him. One day she became annoyed by his heavy breathing (which is just something bulldogs do), so she grabbed his ears and yelled at him. The terrified pup reacted by biting her face. Dorothy was rushed off to the hospital for stitches and a rabies shot, and Toto was rushed off to the vet to be put down.

Dorothy was left with tiny, barely visible scars on her left cheek and upper lip. As far as high society was concerned, though, her beauty was “forever marred.” That was a huge blow to someone whose self-worth was tied up with her good looks. To let everyone know she still had it, she made damn sure that next summer everyone saw her being squired around by the Continent’s most eligible bachelors.

Just in case she didn’t actually have it, Dorothy also decided to be outrageous. The bluenoses spluttered indignantly when she showed up on the beach in the skimpiest of swimsuits (by our standards, a modest two-piece without a skirt). She defended the things high society decried as vulgar, like jazz and the turkey trot. And she never missed a chance to denigrate her countrymen.

Americans have no conception of the artistic or beautiful in life and they show their pitiful ignorance by denouncing something they do not understand.

Dorothy Taylor quoted in “‘Turkey trot’ has many strong foes,” Morning Post, 16 Jan 1912

Outrageous.

Claude Grahame-White

In December 1911 Dorothy was sailing from Cherbourg to New York aboard the Olympic when she caught the eye of fellow passenger Claude Grahame-White.

That name probably means nothing to you unless you’re really into aviation history. Grahame-White was a British aviator who made headlines by completing the first successful night flight, but what really made him a legend was landing a biplane on West Executive Avenue, a little street that runs past some building called “The White House.” He was able to parlay his fame into a business empire, The Grahame-White Aviation Company, which owned and operated aerodromes and built airplanes.

The instant Claude laid eyes on Dorothy Taylor he fell head over heels for the dark-haired beauty with “eyes full of fun.” It wasn’t long before he got a chance to make his move. On the Olympic‘s second day at sea a terrible storm kept most of the passengers glued to the toilets in their cabins, leaving Claude and Dorothy alone in the dining hall. A casual greeting turned into a friendly chat turned into a shipboard romance. They partied like there was no tomorrow. On the last day of the journey, they were even able to persuade the captain to clear out the reading room so they could have a dance party which lasted into the wee hours of the morning.

The next day the lovers were breakfasting in the Royal Suite with their friends, Lionel and Alan Mander, when the ship docked in Sandy Hook. Local reporters had been notified that Claude was one of the passengers, and as soon as the gangplank was lowered they made a beeline for the Royal Suite. Dorothy answered the door. When the reporters asked if Claude was there, she responded:

Oh, yes, Mr. Grahame-White’s here, and we are engaged to be married and please do come in and take our pictures.

Dorothy Taylor quoted in Graham Wallace, Claude Grahame-White: A Biography

Dorothy was joking, but the reporters had no way of knowing that. The following day newspapers ran headlines announcing that world-famous aviator Claude-Grahame White was engaged to New York socialite Dorothy Cadwell Taylor.

Claude was shocked and embarrassed, but also intrigued. The pair did have excellent chemistry. Maybe this could be something more than a fling. Dorothy invited him to dinner at her parents’ house, and it wasn’t long before they were engaged for real.

The Taylors traveled to England in April 1912 to finalize the wedding plans. Shortly after their arrival Claude offered his bride-to-be a rare chance to make history as the first woman to fly over the English Channel (albeit as a passenger). Dorothy chickened out at the last second, and when Claude returned from France she grounded him until the wedding. It was not an auspicious start to the engagement.

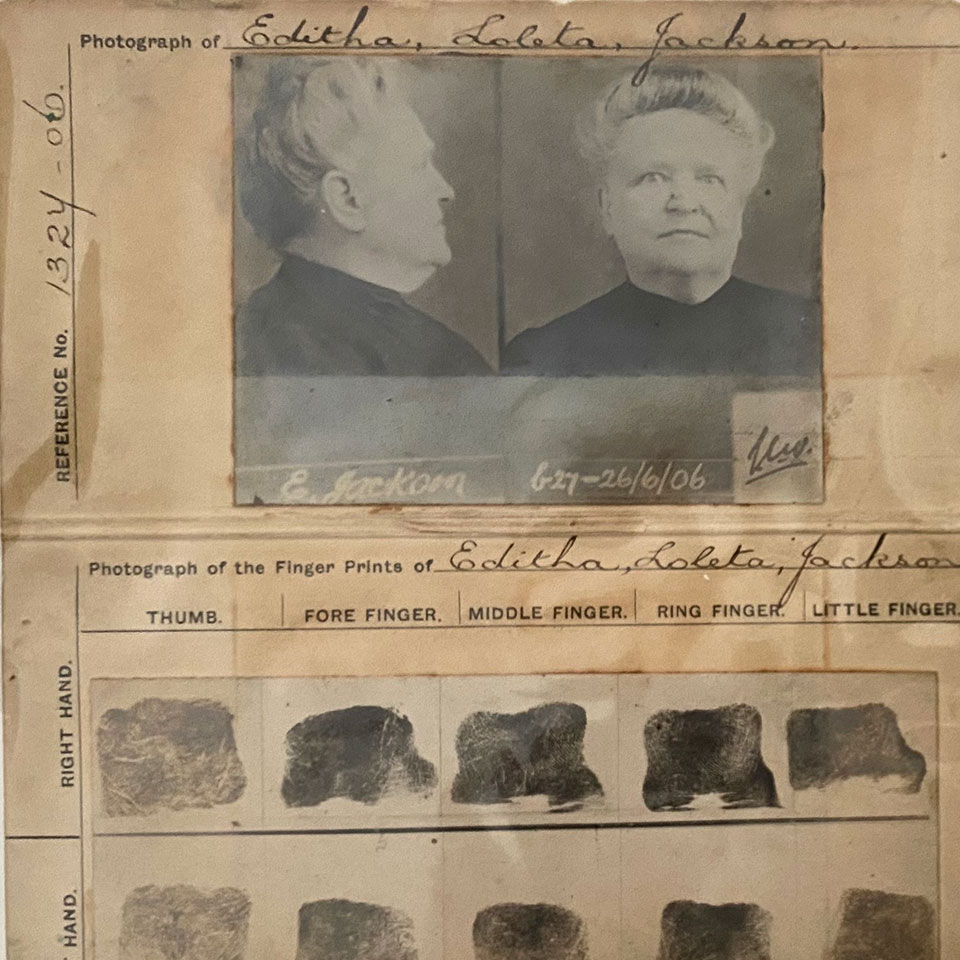

Dorothy and Claude were united on June 27, 1912 in a tremendous spectacle billed as “Britain’s first aero-wedding.” The church was decorated with little airplanes, include a huge arrangement of white lilies in the shape of a biplane that hung over the altar. The guests were a Who’s Who of British aviation: Tommy Sopwith, Gustav Hamel, Jimmy Valentine. The groom flew to the ceremony and parked his plane on the lawn. After the ceremony his friends and students did a formation flyover and dropped confetti. Even the wedding cake topper was a little fondant Nieuport monoplane.

The couple spent a romantic weekend in Paris and then cruised around in a yacht for a week. On the return trip Claude finally flew Dorothy across the English Channel — though her chance to be the first woman to do so had already been seized by one Miss Davies. After the honeymoon they lived in Claude’s flat in London for a few months, then took up permanent residence at a manor house in Kingsbury.

Well, semi-permanent. Fifty years later the Grahame-Whites would have been jet-setters, traveling from continent to continent in search of the next party. For now they made do with taking the train to exotic destinations like Biarritz, St. Moritz, and Rome. Wherever they went, life was a non-stop party with the rich and famous: aviator Chips Drexel; actresses Ethel Levey, Maxine Elliott, and Sarah Bernhardt; songwriter George M. Cowan; singer Enrico Caruso; ballerina Anna Pavlova; inventor Gugliemo Marconi (Marconi, the only name in radio!); Lady Astor and the Grande Duke Alexander of Russia.

Dorothy was visiting friends in Berlin when the Great War started in August 1914, and had to scramble to get back to England before she was trapped behind enemy lines. Claude decided it would be safer for her to return to New York and live with her parents for the duration. She was back less than a year later, though… to file for divorce.

Their marriage had been on rocky ground from the start.

At first Dorothy had been supportive of her husband and his career, but the novelty of being married to a famous aviator wore off quickly. The endless stream of air shows and business functions became boring and repetitive, and she started skipping them so she could stay at home and party with her society friends.

There was also the matter of money. The Grahame-White Aviation Company wasn’t doing very well, but Dorothy couldn’t stop spending like it was going out of style. Those endless parties, those nights at the theater, those fancy dinners at the Savoy? Dorothy was footing the bill for it all.

Claude could have found a way to make the finances make sense if it weren’t for the fact the he wanted children and Dorothy didn’t. It was just one of many things they really should have discussed before the wedding.

Eventually Claude became convinced that Dorothy was a spoiled child without a single thought in her pretty little head, who cared only for a life of hedonism and the hollow delights of high society. There’s a grain of truth in that characterization, but remember that it takes one to know one. Claude loved the endless partying just as much as his wife did, he just couldn’t find a way to afford it.

For her part, Dorothy became convinced that Claude was having affairs — probably because he was. She hired a private detective to follow him around, and was shocked to learn that his mistress was her one-time friend Ethel Levey. (Her shock was lessened somewhat by the hilarious discovery that Ethel had the ceiling of her bedroom painted with a trompe l’oeil sky with a plane descending through the clouds, as if the pilot was going to touch down on her, uh, landing strip.)

Dorothy was still willing to try and work through their marital problems and wrote letter after letter to her estranged husband. Claude was having none of it. He insisted that he had already given her all the chances she was going to get.

I am quite willing and ready to blot out from my memory all that has happened. I have done my best to break off your attachment to the woman who has so far made our lives unbearable, and I hope before it is too late you will give her up and return to me.

letter from Dorothy Grahame-White to Claude Grahame-White, Oct 7 1915

I have written you fully explaining the reasons why we could never live together again with any hope of happiness, and I have never seen any sufficient reason for altering that decision. Since your return to England I have told you verbally and in writing that we are entirely unsuited to each other. I have no wish to reproach you with your conduct, but your written statements do not entitle you to say that another woman has been the cause of our parting.

letter from Claude Grahame-White to Dorothy Grahame-White, Oct 9, 2015

That was it, then. Dorothy filed for divorce… and maybe also started a rumor that Claude and Ethel had been arrested and shot for being German spies. Claude was furious. Bertrand Taylor stepped in to mediate, and offered a deal to his son-in-law: if Claude consented to the divorce, he wouldn’t have to pay alimony. Done and done. The divorce was finalized in December 1916, Dorothy went back to the States with her parents, and Claude married Ethel.

It may have been the biggest mistake he ever made. A few months later Dorothy received a $15 million inheritance and was set for life.

Maybe. Dorothy definitely came into some money, but it’s not clear what the source was. She couldn’t inherit anything from her parents because Bertrand and Nellie Taylor were both still very much alive. She couldn’t inherit anything from her grandparents because they weren’t rich. Any trust in her name would have likely vested years earlier. Her father could have just given her the money, but why now?

So many questions, and so few answers. Mostly because no one’s ever been interested in Dorothy qua Dorothy, so they just take the story at face value and don’t dig any deeper.

Count Carlo Dentice di Frasso

For the next several years Dorothy lived at home with her parents and kept a low profile.

In May 1921 she was back in the headlines when she announced that one of her bracelets had gone missing, and not just any old bracelet: a $40,000 gold bracelet encrusted with diamonds and sapphires that had once been owned by Grand Duke Nicholas of Russia. Fortunately it hadn’t been stolen; she’d accidentally dropped it in the gutter after a party. A friend’s chauffeur found it and returned it a few days later.

If this all seems a bit contrived, that’s because it was. No one, not even the idle rich, casually loses track of a $40,000 bracelet like that. No, this was Dorothy’s way to let everyone know she was back in the game. The bracelet, you see, was a gift from Count Carlo Dentice di Frasso, the Master of the Roman Hounds.

Carlo was the archetypal Italian nobleman, which is to say, handsome, charming, distinguished, and poor as a church mouse. He’d fixed that one defect by marrying New York heiress Georgina Wilde in 1906 in a Downton Abbey sort of arrangement; she got a fancy title, her nouveau-riche family got social respectability, and he got access to their vast fortune. Since love was a secondary consideration at best the couple had an open relationship, though they were still polite enough to keep their affairs on the down low.

By 1921 the marriage had outlasted its usefulness for all the parties involved. It was virtually impossible to get a divorce in Italy, so the couple relocated to New York to get one there (along with an annulment for very Catholic Carlo). Georgina moved back in with her parents, and Carlo moved in with their good friends the Taylors. It wasn’t long before he was putting moves on their beautiful (and extremely wealthy) daughter.

In 1923 Dorothy and Carlo tied the knot. It was either June or July; no one is quite sure when because it wasn’t a pull-out-the-stops extravaganza like her first wedding, just a quiet elopement.

Dorothy got the same deal that Georgina had earlier: he got the money, she got the title, and they could both have as many affairs as they wan ted as long as they kept them discreet. That seemed to satisfy all of the parties involved, though Dorothy did later express some regrets.

I married England’s greatest aviator and the greatest gentleman in Europe, and it’s a toss-up which jerk took me for more dough.

Countess Dorothy Dentice di Frasso quoted in Elsa Maxwell, I Married The World

Some sources act like this was a May-December romance where Dorothy was swept off her feet by a decrepit old Lothario, who then kept her trapped in a loveless marriage. That, at least, was the version of the tale she liked to tell later in life when she was trying to excuse her numerous affairs. In actuality Carlo was only twelve years her senior, and only three years older than Claude Grahame-White.

In 1925 the Count and Countess di Frasso purchased a villa on the outskirts of Rome. Well, I say villa, but this wasn’t any old villa. It was the Villa Madama, an architectural masterpiece designed by Raphael for Pope Leo X and intended to serve as a pastoral Vatican, a testament to the power of the Church and the Medici popes who ruled it while simultaneously celebrating the triumph of secular humanism. It had taken forever to build. Construction was interrupted by Raphael’s death in 1520; Leo X’s death in 1521, and the Sack of Rome by Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1527. When Pope Clement VII died in 1534 the Medici decided to cut their losses and Raphael’s grandiose plans were abandoned, with only one wing and several elaborate gardens built.

You would never know that the Villa was half-finished just by looking at it. Raphael’s students Giulio Romano, Giovanni da Udine, and Baldessare Preuzzi pulled out all the stops when it came to the interior decor and gardens — probably because they were also battling for control of the master’s workshop and saw the Villa as a chance to stake their claim for supremacy.

Over the years the Villa went through several names and owners, ultimately becoming known as the Villa Madama after its most famous resident: Charles V’s daughter Margaret of Austria, who was married to both Alessandro de Medici and Ottavio Farnese. After Margaret died the Villa passed from the Farnese to the Bourbons, and then through several wealthy private owners.

One of the ways those private owners stayed wealthy was by skimping on building maintenance. By 1925 the Villa had fallen into disrepair. The floors were mildewed and warped, the ceiling sagged, the walls were stained, the frescoes faded, the gardens overgrown.

The Count and Countess di Frasso started restoring the Villa to its former glory, and were ideally suited to the task — Carlo had the taste, and Dorothy had the money. They spent more than $1 million sprucing the place up. They also made numerous improvements: installing elevators, upgrading the plumbing and wiring, and supplementing the interior decor with rich silk curtains and Renaissance paintings.

Once renovations were complete the Count and Countess threw a huge party, a nine course dinner for two hundred people, featuring guest of honor being Crown Prince Umberto. It made the couple internationally famous and established them as the premiere host and hostess of Italy.

They hosted a lot, because the Countess was a 24-hour party person. One of her society friends, heiress Barbara Hutton, later recalled:

It was hard to tell whether the Countess threw one party that lasted all summer or a series of weekend parties that lasted all week. Guests just came and went as if the Villa Madama were a Grand Hotel.

Barbara Hutton quoted in Jeffrey Meyers, Gary Cooper: American Hero

Through hosting parties the Countess made the acquaintance of party planner and future gossip columnist Elsa Maxwell. Dorothy and Elsa discovered that they enjoyed each other’s company and became fast friends. It didn’t hurt that their business interests dovetailed; Elsa needed Dorothy’s money to finance her extravagant parties, and Dorothy needed Elsa’s connections to keep her name in the headlines.

Once the Count and Countess di Frasso were on top of the world they started letting the mask slip and show their ugly sides. Everyone already knew they were superficial and vain; that was just part and parcel of being Italian aristocrats. They were also huge Fascists who donated their money and political capital to Mussolini. They could be racist AF, and once ordered all the Americans out of a Paris nightclub when the owners allowed a black woman onto the dance floor. Dorothy also developed a reputation for being thin-skinned and petty; she once tried to get Noël Coward blackballed from Venice for the unpardonable offense of being wittier than her, and when Elsa took Coward’s side it led to a vicious catfight where both women had to be forcibly separated, taking huge chunk of each other’s hair with them.

Gary Cooper

One day in 1931, the Countess came back from a shopping trip and was informed that there was someone waiting for her in the sitting room. She hadn’t been expecting anyone, so when Elsa told her the visitor was a short, dull fellow she was in no rush to meet him. When she finally did drop by to say hi she got the shock of her life.

The visitor was neither short nor dull. The visitor was Gary Cooper.

By 1931 Cooper was one of the biggest movie stars in the world, acting in five films a year and sometimes two at once. Off-screen, though, his life was a shambles. He was trapped in an abusive relationship with the jealous “Mexican Wildcat” Lupe Vélez. He was constantly arguing with his mother, a moralistic taskmaster who didn’t like Lupe. He was also teetering on the edge of financial ruin, as both lover and mother were spending money faster than he could make it.

These stresses eventually started to take their toll on Cooper’s health. His weight dropped to 148 pounds and he started showing symptoms of jaundice. His doctor told him he needed to take a year off to rest or he would die. Paramount said he could have five weeks off, and he was glad to get it. He immediately left for a European spa vacation. On his way out of Hollywood he was ambushed by Vélez, who cursed and fired a pistol over Cooper’s head as his train pulled out of the station.

Cooper spent a few weeks at the spa and then made his way to Rome. Producer Walter Wanger had helpfully suggested his star should drop by the Villa Madama to meet the Count and Countess di Frasso, who ran a “sort of open house for celebrities… dignitaries… royalty on the loose… other congenial characters.” He did just that, with a letter of introduction from Wanger in his hand.

The Countess took one look at the “half-smiling, pathetically thin Adonis” thirteen years her junior and immediately fell in… love? Lust? Does it matter? She was determined to have him. Cooper was all for it. He was always looking for the next big role, and “side piece of a debauched European noblewoman” sounded pretty good to him.

It was a whirlwind romance. The Countess took Cooper on tours of Italy’s greatest monuments and museums. They went car racing, they went horse riding, they even went hunting with the Italian cavalry. They washed down the richest food with the finest wine. She bought him a brand new wardrobe of the sharpest suits. She educated him on style and manners and introduced him to a better class of people, people like Marjorie Merriweather Post, Barbara Hutton, Crown Prince Umberto, and the Duke of York. They were having so much fun that Cooper made the unilateral decision to extend his five week vacation.

Paramount was none too happy about that. They figured that if their star was well enough to canoodle with a Countess he was well enough to get back to work. They sent several telegrams ordering him return. Cooper ignored them, so Paramount decided to play hardball. They fired him from George Cukor’s Girls About Town and replaced him with Anderson Lawler.

Cooper’s next picture was supposed to be Edward Sloman’s His Woman. It was a rare chance to act opposite Claudette Colbert, and he wasn’t going to lose that role to goddamn Anderson Lawler of all people. He started packing his bags. The Countess tearfully begged her lover to stay, even offered to divorce her husband. Cooper was usually putty in the hands of a beautiful woman, but this time he could not be swayed. He said his goodbyes and went back to Hollywood.

A few weeks into the shoot Cooper got a surprise invitation to go on an African safari from a casual acquaintance, a wealthy horse breeder named Jerome Preston. Why the hell not, he figured. After production wrapped he took a plane to Naples, an ocean liner to Alexandria, a barge up the Nile, and made his way to the shores of Lake Nyasa in Tanganyika… where he was surprised to meet the Countess di Frasso, dressed like Coco Chanel if she were going after Dr. Livingstone. It turned out Preston was a friend of hers, and she had arranged the whole safari so she could spend a few more weeks with her lover boy.

It was actually a pretty good safari. In addition to bagging the Countess di Frasso, Cooper also bagged two lions and sixty head of game; permanently damaged his hearing by screwing around with an elephant gun; and adopted a chimp named Toluca as a pet.

The Countess was pretty pleased with herself, though she seemed to be missing the signs that just maybe Cooper wasn’t as into her as she was into him.

The sun was setting. Gary was sitting by himself with an elbow on his knee… looking down at the ground. It was one of the most beautiful pictures I had ever seen. “Oh, darling,” I said, “what are you thinking?” He looked at me for a minute and said, “I’ve been wonderin’ whether I should change my brand of shoe polish.”

Countess Dorothy di Frasso quoted in Jane Ellen Way, Cooper’s Women

In February 1932 the rainy season brought the safari to an end, and the lovers decided to take the party to the Riviera for sea, sand, sun, and sex. Once back in Europe they were joined by the Count di Frasso, which had to be a little weird for everyone.

Paramount was not happy when they finally discovered where their star had gone. Producer William Goetz ruefully joked, “I’ve always wanted to go to Europe on the Countess di Frasso,” and then put a hold on Cooper’s salary. Cooper was lucky. The studio would have fired and blacklisted anyone else who pulled a stunt like this.

Cooper didn’t realize what had happened until started running out of money at the casinos of Monte Carlo. He briefly considered retiring to become the Countess’s full-time side piece, but then he heard that some newcomer named “Cary Grant” was being groomed to take his place. What really freaked Cooper out was that Grant’s initials (“CG”) were the reverse of his own initials (“GC”).

He started packing his bags. Once again the Countess tearfully begged her lover to stay, promised she would divorce her husband, even offered to purchase the entire movie studio and give it to him. She was clearly terrified by the idea of losing him. Cooper thought it was “cute,” but he also felt like he’d had his fun and it was time to get back to work.

Though, uh, in order to do that he had to borrow some money from her because he was flat broke and couldn’t afford a plane ticket home.

The Countess asked Elsa Maxwell to keep tabs on Cooper. She was worried that someone else would steal away his affections. Maybe one of his exes, like Clara Bow or Lupe Vélez. Maybe someone new like Tallulah Bankhead, who once described her career goals in Hollywood as “I’m here for the money and to f*** that divine Gary Cooper.” It didn’t help that Cooper’s next film was Devil in the Deep… co-starring Tallulah Bankhead.

She didn’t need to be worried. Cooper may have been back to work but he was still upset with how the studio was treating him. He was sluggish and sullen off-camera, barely interacted with his co-stars, and skipped out on parties and publicity junkets. Bankhead explained away Cooper’s behavior with an impish quip: “He’s probably worn to a Frasso!”

The Countess was worried anyway. She arrived in Hollywood not long after Cooper did, ostensibly to sell some footage she’d taken of their African safari but really so she could stake her claim to Cooper’s loins. Cooper had been sort of hoping their affair was over, but now realized the Countess’s love was “a cashmere-lined straitjacket” that he would have a hard time escaping.

You may find yourself wondering why Gary Cooper, the most famous movie star in the entire world, would put up with any of this. Well, in addition to being an enormous himbo Cooper was also a total pushover, conditioned by his mother to unthinkingly obey any woman in a position of authority. That was one of the reasons he’d stayed in his abusive relationship with Vélez for so long. The only way he knew how to deal with conflict was to avoid it, which was hard to do when the Countess kept turning up everywhere he went like a bad penny.

At first the Countess booked a room at the notorious Garden of Allah. Then she was invited to stay with Mary Pickford until she could find more permanent accommodations. The problem was that she seemed in no rush to find more permanent accommodations. Pickford was not happy, though the Countess did not pick up on those vibes. Well, at least not until September. The Countess, Cooper, and Pickford were going to take a trip to Italy, but while they waited at the station Pickford left to pick up a telegram at the gate… and never came back.

The Countess finally got the hint. She purchased a mansion in Beverly Hills, a short walk from Cooper’s own. She hired legendary interior designer Elsie de Wolfe to turn it into “the ultimate art deco house,” where “chinoiserie wallpaper met a fluffy rug made of monkey fur.”

Once she had a permanent a base of operations, the Countess got back to what she did best: throw parties. She sent out countless invitations to Hollywood bigwigs, using Cooper’s fame and her infamy as a sort of lure. Her first big bash was literally a big bash: her guests were treated to three amateur boxing matches at a ring set up in the back yard.

It wasn’t long before the Countess di Frasso was the top hostess in Hollywood. If you received an invitation to one of her soirées, you knew you had made it. Guests rubbed shoulders with Hollywood royalty like Fred Astaire, Lionel Barrymore, Charles Boyer, Dolores Del Rio, Marlene Dietrich, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Clark Gable, Samuel Goldwyn, Frederick March, Norma Shearer, Irving Thalberg, Fay Wray, and Loretta Young. She even extended invitations to that young up-and-comer Cary Grant, much to Cooper’s distress.

David Niven would later recall that the Countess’s “luncheon parties melded into tennis and swimming parties, and the afternoon parties went on till the early hours of the morning.” He also engaged in a bit of pop culture psychoanalysis, theorizing that the non-stop partying was a pathetic attempt to stay young and relevant. (He wasn’t necessarily wrong.)

Eventually, though, all good things must come to an end. In early 1933 Cooper met bit player Veronica Balfe and fell head over heels for her. The Countess tried to fight for her man by losing weight, dressing younger, and throwing ever more extravagant parties. She only realized she was losing the battle when Cooper started ghosting her, because she knew avoiding conflict was the only coping mechanism he had. Still she fought on, though the only tools left in her toolbox were grand gestures.

In July 1933 she announced that she was going to move to Reno so she could get a quickie Nevada divorce from the Count and marry Cooper. She had hoped that would force her lover to come to her, if only to ask what the hell she was doing. It didn’t work. Then she announced she was flying back to Italy forever, hoping Cooper would come to his senses and rush to the airport to stop her like the end of some hacky rom-com. He didn’t.

Cooper and Balfe married in December 1933. The Countess came slinking back to Hollywood a few weeks later. She acted like she was fine, claiming she wanted to be friends with the newlyweds, but behind the scenes she was actively working to undermine their marriage by spreading malicious rumors about them through her friends Elsa Maxwell and Hedda Hopper.

Balfe wouldn’t have any of it. She invited the Countess to lunch at the Mocambo, with Lupe Vélez serving as a sort of mediator. There she returned several gifts that the Countess had given to Cooper, including an Afghan hound and several expensive jeweled tie studs and cuff links. The Countess tried to force Balfe to keep them, but Balfe remained adamant, and the Countess left in a huff. Vélez cackled throughout the whole thing, like she was having the time of her life.

That was that. Cooper still kept in contact with the Countess over the years, partly out of gratitude, partly out of guilt, and mostly because her social connections made crossing her dangerous. But their affair was over.

Alone

The Countess would just have to settle for being Hollywood’s hottest hostess. With Elsa Maxwell’s help, she threw some of the craziest and outlandish parties the movie industry had ever seen.

In April 1935 the Countess once again staged boxing matches in her backyard. This time, though, the drunken revelry got out of hand and two guests started pummeling each other for real in the foyer and had to be separated by the police. The Countess tried to spin the tussle as an elaborate April Fool’s joke, but no one bought it because April Fool’s Day had been a week earlier.

In June 1935 she threw a costume party where guests were instructed to come dressed as someone from history they admired. The Countess herself dressed as Stravinsky’s Firebird (which is sort of cheating), but her good friend Marlene Dietrich was the one who made headlines by dressing as Leda, a costume that consisted of a skimpy dress in the shape of a swan. (And if that sounds familiar to you, it’s because Björk wore a recreation of that dress to the Oscars in 2001).

In December 1935 she held a “Red and White” party, which doesn’t sound all that exciting. The twist was that before the party the Countess had her staff hide microphones around the house which she used to surreptitiously record her guests… Guests that included influential people like John Barrymore, Claudette Colbert, George Cukor, Marlene Dietrich, Betty Furness (for Westinghouse), William Haines, Olive McClure, Clifton Webb, and Cary Grant (rumor had it he was the new Gary Cooper). A few weeks later she invited the same group back to her house for brunch, where she “entertained” them by playing back the secret recordings. The Countess laughed with delight to hear the catty critiques, witty insults, and sly innuendoes. Her guests were horrified to hear their dirty laundry aired in public. They established a united front and forced her to destroy the recordings.

She tried the same trick again a few months later, but this time Ann Sheridan accidentally stumbled across one of the hidden microphones and warned the other partygoers. When the Countess listened to the playback, the only thing she heard was malicious gossip about herself. She retired the trick after that.

In 1938 the Countess and Elsa staged “The Old English Costume Ball,” where guests were stopped at the door and helped into costumes resembling Eighteenth Century court dress, including wigs, lorgnettes, and swords — all made of inexpensive and colorful paper. The Countess made herself the center of attention by repeatedly changing costumes throughout the evening, building up to a spectacular Marie Antoinette outfit that included a gigantic powdered wig and a set of false teeth.

The party was a smashing success, until some unnamed starlet got blackout drunk and started screaming. Her escort put a roofie in a glass of champagne and tried to get a server to take it to her, but the server was intercepted by Leslie Howard who chugged it and passed out. A second roofie was given to the screaming starlet and she and Howard were dragged upstairs and put in a guest bed to sleep it off. The Countess sardonically looked at the two and sighed, “The joint looks like a funeral parlor with those two.”

As for her love life, well, the Countess continued to have affairs with everyone in Hollywood who wasn’t Gary Cooper. Her sexual conquests included director Johnny Farrow; screenwriters Rowland Brown, Willis Goldbeck, and Ben Hecht; actors Reggie Gardiner, William Powell, Lyle Talbot, and Tom Tyler; Olympic bobsledder Freddie McEvoy; a parade of aristocratic European himbos; and even Cary Grant (I hear he’s the new Gary Cooper).

She could often be found at the Hollywood Bowl, sitting next to Lupe Vélez and watching the fights. Vélez would loudly cheer on the Mexican boxers, the Countess would cheer on the Italian boxers, and they competed to see which of them could be the most obnoxious. One day a handsome young Italian boxer (possibly Enzo Fiermonte, but probably not) scored a singularly impressive victory. The Countess charged the ring and was kissing him on the lips before the timekeeper could start ringing the bell. Despite her initial enthusiasm the relationship only lasted a few weeks. One Saturday the boxer was knocked out in the first round and limped back to the locker room to find out he had been dumped while he was unconscious.

In 1937 the Countess had an affair with bit player and catalog model William McCoy, and invited him to spend the summer with her in Paris. She wrote McCoy a $2,000 check to cover his travel expenses, but McCoy decided to stay in the United States with his wife instead. The Countess asked for her money back, but McCoy had already spent it and wasn’t in any rush to repay her. At least, not until the Countess called Jack Warner to complain. The combined wrath of the Warner Brothers proved to be a great motivator.

Her bad luck and bad taste in men were so well-known that they were satirized in Clare Boothe Luce’s 1936 play The Women, an ensemble piece about several women living in a group home in Reno so they can establish residency for a no-fault Nevada divorce. One of them is the Countess de Lave, an extravagant romantic who has thrown everything she has away to make a success out of cowboy actor Buck Winston, who then dumps her for a much younger woman. Any resemblance to real persons living or dead was purely coincidental, I’m sure.

The Countess’s post-Cooper sex life was mostly quick flings and one-night stands, but she did have one significant long-term relationship. The problem was that it was with the worst possible person.

Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel

In early 1933 the Countess went to Santa Anita to watch the races. One member of her entourage, hotelier James McKinley Bryant, spotted an old friend of his over at the betting window. He called the young man over and they had a quick chat.

And that is how Countess Dorothy di Frasso met Benjamin Siegel, better known to his friends as “Bugsy.”

The popular image of Bugsy Siegel is that he was a naïve dreamer who had grand plans for developing Las Vegas, only to be denied because his reach exceeded his grasp. That phase of his life was a decade in the future, though. At this point in his life he was just a jumped-up thug, one of the leading figures in the National Crime Syndicate and its enforcement arm, Murder Inc.

By 1933 it was obvious that Prohibition would be repealed, so the Syndicate began looking for alternative revenue streams. The motion picture industry was one of the few industries in America turning a profit, so Siegel was sent to California. His assignment was to ingratiate himself into the Hollywood elite and identify business opportunities for the Syndicate. His cover was that he was a “sportsman,” which was vague enough that he could conceivably go anywhere and do anything.

He quickly made friends with actor George Raft, best known for playing mobsters and hoods in films like Scarface. That was great for Raft; he was a marshmallow in real life and palling around with an actual tough guy gave him some street cred. It wasn’t so great for Siegel, because the tough guy vibes scared everyone else off. As a result his influence was limited to actors who were already mobbed up to some degree.

And one idiot who was too blinded by love to see his true nature. The Countess locked eyes with Siegel at the Santa Anita Racetrack and was instantly besotted with the handsome young gangster eighteen years her junior.

The Countess decided to make Siegel her next project. She took him out dancing, invited him to parties, introduced him to Hollywood society, and eventually charmed him into her bed. It was a relationship that benefitted them both: the Countess got a handsome boy toy on her arm who made her feel young again, and Siegel finally got the connections he so desperately needed.

The Countess and Siegel actually made a pretty good couple, because were very like minded. One big thing they had in common was that they loved betting on long shots and get-rich-quick schemes.

Now, you might find yourself wondering why someone as wealthy as the Countess would be interested in get-rich-quick schemes. The short answer is, the Countess wasn’t actually all that wealthy.

The first cracks in her facade appeared in 1934 when her father Bertrand Leroy Taylor Sr. passed away. His will was contested by Geraldine Ott, a Kansas divorcee turned exotic dancer turned nightclub singer, who claimed to be Bertrand Sr.’s “common law widow” and therefore entitled to his entire $15,000,000 estate. Ott’s claims were eventually shot down — it turned out her “engagement ring” was a cheap $5 band from a pawn shop — but the challenge revealed that the Taylors weren’t nearly as rich as everyone had thought.

Most of Bertrand Sr.’s wealth had been tied up in the stock market and it taken a real hit on Black Monday in 1929. He wasn’t completely ruined, but his subsequent investments didn’t pan out and he found it hard to check his extravagant spending. That fabulous estate just kept getting smaller and smaller, and by the time of his death it was only worth $1,200,000. Which is a lot of money, especially in 1935, but not “I have mansions in New York and Beverly Hills but spend most of my time at a Renaissance Villa in Rome” money.

The Countess had been counting on her inheritance to help finance her lifestyle, and when it became clear it wouldn’t she started indiscriminately sinking her money into any investment she could find that might pay off big. She teamed up with actress Constance Bennett to try and break into the cosmetics industry. That partnership ended after an argument, so she tried to break into the cosmetics industry on her own. She spent a small fortune trying to turn soybeans into a thing, which was a great idea but about twenty years too early.

These ideas could have borne fruit if the Countess stuck with them, but she never did. In the end she was reduced to raising money any way she could. She leased her limousine to movie studios for $150 a day. She leased her mansions to the nouveau riche. She even wound up leasing her pride and joy, the Villa Madama, to the Italian government, which used it as a residence for visiting diplomats.

By 1938 the Countess could no longer afford sipping cocktails at the Waldorf-Astoria and was reduced to downing beers at dive bars in Brooklyn. She was at one such bar when Bill Bowbeer, part-time prospector and full-time drunk, sidled up to her table, sat down, and told her a tale of buried treasure.

Back in 1821 the spirit of revolution was sweeping across South America. As the rebel army marched on Lima, the Viceroy of Peru panicked. He chartered a British ship, the Mary Deere, and loaded it to the gills with doubloons, bars of gold and silver, gems, jewels, and fabulous art (including a life-sized solid gold statue of the Virgin Mary encrusted with precious stones).

Captain Thompson of the Mary Deere was instructed to sail away and see how the revolution fared. If the Spanish won, he should return to Lima; if the rebels won, he should take the treasure up to Mexico. Captain Thompson chose option number three: he murdered his Spanish minders and stole the treasure.

When the Spanish realized they’d been tricked they set out in hot pursuit. Captain Thompson stopped on Cocos Island to ditch the treasure. He knew the remote island would be a safe pace to stash his ill-gotten gains — the legendary pirate Benito Bonito had buried his own treasure on Cocos Island decades earlier, and no one had ever found it.

It was a pretty good plan, until it wasn’t.

The Spanish caught the Mary Deere and hung the crew as pirates. Captain Thompson and his first mate John Alexander Forbes were spared, on the condition that they lead the Spanish to the buried treasure. Once they reached Cocos Island, Thompson and Forbes somehow escaped their captors and fled into the jungle, out-waited the Spanish, and lived as maroons for years until they were rescued by a passing American whaler.

Captain Thompson died shortly after the rescue. Forbes settled in California and got so wealthy during the Gold Rush that it was hardly worth going back for the treasure, though he did draw a map showing its location and gave it to his eldest son Charles.

After Bowbeer finished his story he looked the Countess right in the eye and declared that he had that Forbes family map. He even borrowed her lipstick and made a quick sketch from memory on the tablecloth.

Now, you or I would probably roll our eyes at that cock-and-bull story and ask Bowbeer if it ever actually worked. I mean, really, Benito Bonito? That’s clearly a fake pirate from a children’s book. If we were in a good mood we might even offer to pay for his beer.

Countess Dorothy Dentice di Frasso told Bowbeer she was all in, shook his hand, then called Bugsy Siegel and told him to get a boat.

Siegel spent $17,000 to charter the Metha Nelson, a three-masted schooner that had been used as a set for several movies including the Clark Gable and Charles Laughton version of Mutiny on the Bounty. Then he scraped together a crew of about two dozen gangsters and ne’er-do-wells who had never been to sea before. There was the Countess, of course; her lady’s maid Filomena Renzi; Bill Bowbeer and his treasure map; Bugsy Siegel; “Champ” Segal, no relation, Bugsy’s personal trainer; Dr. Benjamin Blank, who had gone to medical school with Bugsy’s brother Maurice; Jean Harlow’s stepfather Marino Bello, and his nurse Evelyn Husby; and Jack Warner’s right-hand-man Richard Gully. Commanding this motley crew was Captain Robert B. Hoffman, a German martinet who clearly had his work cut out for him.

On September 10, 1938 the Metha Nelson left port on a voyage that was subsequently called “one of the daffiest cruises in the annals of the sea.”

The expedition’s cover was that they were shark fishing, to fulfill a contract with the German Navy for shark oil. It was such an obvious lie that it encouraged public speculation about what they were actually up to. Hedda Hopper thought the Syndicate was trying to establish a new heroin smuggling route. The FBI thought Siegel was trying to make contact with his old pal Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, who was supposed to be hiding on an island somewhere, and asked Captain Hoffman to keep an eye out for the fugitive. (The FBI was half right; Lepke was hiding on an island but it was Coney Island.)

For the most part the trip was quiet. They worked all day, drank all night, listened to records on the phonograph, played cards, and discussed how they would spend a treasure that they hadn’t yet found and which probably didn’t exist.

Several of the crew began fighting for the affections of Evelyn Husby, the only attractive and available woman on board. Marino Bello temporarily solved that problem by marrying her. Captain Hoffman officiated, the Countess was the matron of honor, and Siegel was the witness. That stopped the fighting, though if anyone thought about it for a second they would have remembered that sea captains don’t actually have the authority to marry people.

The Metha Nelson reached Puntarenas in late September, where the crew signed a pro forma agreement to give the Costa Rican government a third of anything they found on Cocos Island and took on six soldiers to serve as a military escort.

The Costa Ricans thought the Metha Nelson was on a fool’s errand. Fortune hunters had been searching for the treasure of Cocos Island for over a century without success. A German treasure-hunter named August Gissler made a systematic search of the island for over two decades and found nothing. If there had ever been a treasure it was long gone… but just in case the Metha Nelson did find something, the Costa Ricans wanted to make sure they got their cut.

They also wanted Mrs. Bello, or Miss Husby, or whatever you want to call her. One local officer took a fancy to her and began making crude passes, so Marino Bello challenged him to a duel. In the cold light of day the fifty-one-year-old Bello thought better of it, and made sure the Metha Nelson was back out to sea before made him follow through.

Eventually they arrived on Cocos Island which, to be frank, was a bit of a dump. The shores were steep rocky cliffs, and the hilly interior was overgrown with vegetation and overrun with wildcats, boars, snakes, rats, and red ants. It was hot and muggy and uncomfortable. But that was where the treasure was, so there was nothing to do but go ashore and dig.

Did we dig? Christ, did we dig! We drilled through rocks and shale. The climate was murderous but we couldn’t stop. We dynamited whole cliffs.

Richard Gully, quoted in Dean Jennings Southern, We Only Kill Each Other

They dug. And dug. And dug, and dug. The fruits of their labors were meager: rusty nails, old boots, and the cast-offs of a century of fortune hunters. As the days wore on there was less digging and more drinking. Drinking and grumbling.

The Countess, of course, was not involved in any of the digging. She stayed in her cabin for most of the trip, supposedly “supervising” the operations but mostly just drinking and complaining about the heat.

After ten days of this the crew of the Metha Nelson decided to call it quits. They sailed up to Panama, where Bugsy Siegel flew back to California. Siegel’s excuse was that he was worried about how his bookmaking operation was faring, but in reality he was just angry that he’d been suckered into a wild goose chase by a skirt who wasn’t even all that pretty.

The Countess was pretty miffed that her erstwhile paramour had abandoned her, and decided to get even by making a drunken pass at Champ Segal. Champ knew that he would get a beating or worse for messing with Bugsy’s girl, and passed. That made the Countess angrier, so she went to Captain Hoffman and told her Segal was plotting to hold her for ransom and demanded that he be shot. Hoffman respectfully declined.

That was unusual because Captain Hoffman was, to put it mildly, a bit of a Nazi — not just metaphorically, an actual Nazi. When two members of the crew, Abraham Kapellner and Charles Segal (no relation) started getting insubordinate he whipped them with chains and called them every anti-Semitic slur he could think of. That was the final straw for Kapellner and Segal, who jumped ship in Guatemala and boarded Italian ship bound for Los Angeles, the Cellina. When Hoffman found out he radioed the Cellina and falsely claimed that the two men were mutineers. They were promptly thrown into the brig.

A few days later Captain Hoffman steered straight into a typhoon. The sails were destroyed and the crankshaft of the diesel engine was seriously damaged, leaving the Metha Nelson dead in the water. It drifted aimlessly for three days before another ship responded to their S.O.S… the Cellina, as it happened. It gave the Metha Nelson a tow back to Acapulco. Everyone who could afford it flew back to Los Angeles.

When the Metha Nelson finally made it back to Los Angeles in January 1939 the FBI pounced on it in an attempt to catch Lepke, who at that very moment was several thousand miles away eating a hot dog at Nathan’s and trying to decide whether he wanted to ride the Cyclone or the Wonder Wheel.

Everyone else found themselves dragged into the escalating fight between Captain Hoffman, Kapellner, and Segal. Hoffman had his former crew members arrested and tried to have them charged with mutiny, but as a grand jury began investigating the incident Hoffman seemed less and less like Captain Smollett and more and more like Captain Queeg. The grand jury declined to indict anyone and Hoffman slunk back to Germany.

The public couldn’t hear enough about the doomed voyage of “the Hell Ship” and it was front page news for several weeks. It was the first time anyone outside the FBI heard the name “Bugsy Siegel” associated with the National Crime Syndicate. When people in Hollywood discovered they had been palling around with a mobster they were shocked and horrified and angry.

Some of that anger was directed at the Countess, who many people felt had been deliberately trying to launder Siegel’s reputation. Humphrey Bogart decried “the clique of ex-bootleggers and phony baronesses that get all dressed up in chinchillas and tailcoats to see the world premier of a movie.” The Countess fought back, claiming that Bugsy was an innocent boy, someone she could mold into the perfect gentleman.

I don’t care what others think, but to me Ben is a kind of knight. If he had been living in the time of King Arthur, he would have been a gallant member of the Round Table.

Countess Dorothy di Frasso quoted in Dean Southern Jennings, We Only Kill Each Other

No one was buying it. The Countess’s now-public relationship with Siegel basically killed her career as a Hollywood hostess. Fewer and fewer people attended her parties, and her influence began to wane.

In March 1939, German flying ace Raven Erik Freiherr von Barnekow, who was dating Kay Francis at the time, suddenly announced to the press that he was going to sue the Countess for slander after she called him a Germany spy. “I am an American citizen, and I am a manufacturer of motors, and such false remarks as this may damage my business.”

The Countess was baffled, for several reasons. For starters, Barnekow was a German spy and everyone knew it. Second, he wasn’t an American citizen. And finally, she barely knew him. “I haven’t seen the Baron Barnekow in weeks. I didn’t know the baron in Europe or Germany. I do not know what his politics are, and I must say, I couldn’t care less.”

Barnekow, it seems, was trying to divert public ire from himself and onto a then-hated figure. It didn’t work, and his accusations were soon forgotten.

As that little kerfuffle died down, Siegel and the Countess heard rumors about a brand-new type of explosive hundreds of times more powerful than TNT called either “radium-atomite or just plain old “Atomite.” (In spite of the sci-fi name it wasn’t some sort of atomic wonder weapon, just a regular old explosive.) They sought out the two chemists who were developing it, Thomas S. Hamilton and Michele Bonotto, who blew up a couple of mid-sized boulders in the Imperial Valley to demonstrate their product. The Countess was so impressed she became their principal investor, sinking some $50,000 into product development.

In the summer of 1939 Dorothy asked her husband Carlo (remember him?) to try and sell the new explosive to the Italian government. Mussolini was interested — very interested. He advanced the Countess $40,000 to scale up the production of Atomite and asked for an in-person demonstration at her earliest convenience.

The Countess packed her bags for Italy with stars in eyes. She could already envision her latest triumph. She would bowl over Il Duce with her amazing new explosive, and give Siegel the same glow-up she had given to Gary Cooper. She would dazzle her lover with the Villa Madama and the splendor of Rome, introduce him to European society, and win his heart forever.

In that sense, at least, the trip was a triumph.

I’m telling you, this joint was bigger than Grand Central Station, and half the guys she had hanging around were Counts or Dukes or Kings out of a job.

Bugsy Siegel quoted in Dean Southern Jennings, We Only Kill Each Other

The Countess introduced the awe-struck Siegel to numerous world leaders including Benito Mussolini; Prince Aimone, the Duke of Aosta; King George II of Greece; Crown Prince Umberto and King Victor Emmanuel II of Italy; and Pope Pius XII. For some reason she chose to introduce him as “Bart” Siegel, which Crown Prince Umberto mis-heard as “baronet.”

He acted oddly for a baron. He tried to sell us dynamite.

King Umberto II of Italy quoted in Elsa Maxwell, I Married the World

In every other sense the trip was an utter failure.

The Atomite failed to explode in test after test after test. The Countess and Siegel complained of sabotage, but the truth was much more mundane: to save money they had left Hamilton and Bonotto back in the States, so there was no one around who could fix any technical problems that arose. In any case, the new super-explosive wasn’t actually all that super in the first place. It just had great marketing.

Mussolini was not amused. He demanded his money back, and he got it. Then, just out of spite, he kicked the Countess out of her own house to make room for two visiting diplomats: Joseph Goebbels and Hermann Göring.

Siegel wasn’t a particularly good Jew by any measure, but the thought suddenly crossed his mind that maybe he could do the world a solid by shooting a few Nazis. The Countess panicked and tried to talk him out of it. It was a suicide mission, after all, and whether he succeeded or failed he would be taking the Count and Countess di Frasso down with him. Siegel calmed down, and then flew back to Los Angeles.

(Michele Bonotto continued to work on Atomite and by the early 1950s he had developed it into a sort of jellied explosive. The Countess wound up with ownership of the patents, though she didn’t actually do anything with them.)

At this point in late 1939 Lepke Buchalter was finally ready to come in from the cold and take one for the team, but one of his conditions was that Murder, Inc. bigwigs had to personally take care of his enemies first. Siegel was given the job of taking out Harry “Big Greenie” Greenberg, which he did by boxing in Big Greenie’s car and filling him with so much lead he could use his d*** for a pencil.

Siegel screwed up the hit, leaving behind a trail of evidence that led right to him. He was arrested and hauled off to the Los Angeles County Jail — sort of. He barely spent any time behind bars because the jail’s doctor kept giving him day passes for medical reasons. That doctor was Dr. Benjamin Blank, a friend of Siegel’s brother Maurice from medical school and former ship’s doctor of the Metha Nelson. When Blank’s actions were discovered there was a huge scandal, though it would hardly be the first or last time a celebrity got preferential treatment at the Los Angeles County Jail.

Also scandalous was the fact that the Countess was using her social connections to apply pressure on District Attorney John Dockweiler in an attempt to get him to drop the case. Dockweiler did drop the charges, but it had nothing to do withe her lobbying. His problem was that New York authorities wouldn’t let key witnesses like Abe “Kid Twist” Reles and “Tick Tock” Tannenbaum travel, which basically torpedoed his case.

Charges were eventually re-filed in New York and Siegel was re-arrested. By now his alibi was that he could not have possibly been involved in Big Greenie’s murder because at the time he and the Countess had been in Italy. This was a transparent lie — the timelines did not sync up at all — but the Countess backed him up.

It didn’t matter. The New York district attorneys had Siegel dead to rights — or at least they did until their star witness, Kid Twist, died unexpectedly. (The Kid either fell out of a sixth story window trying to escape police custody, or was thrown out of a sixth story window by crooked cops.) Once again the charges were dismissed and Siegel was a free man.

The end of the trial was also the end of Siegel and the Countess’s romantic relationship. She had used all of her remaining influence to support her paramour, which made her useless to him. He began fooling around with actress Wendy Barrie before eventually going more-or-less steady with Virginia Hill. The Countess was not pleased when she learned that her self-sacrifice would not be rewarded, and vented to George Raft that she would kill anyone who was fooling around with her man.

Alone Again

Once again the Countess was alone… well, okay, she still had Carlo half a world away, for whatever he was worth. She kept herself amused with a series of one-night stands and short-term flings and by playing matchmaker for her friends. Most famously she kept trying to get her good friends Barbara Hutton and Cary Grant to hook up even though the two of them had very little in common.

Eventually politics gave her something bigger to worry about. Throughout 1940 it became increasingly clear that the United States would enter World War II on the side of the Allies.

The Countess didn’t think that would work out well for her, and she was probably right. Okay, sure, she had authoritarian leanings, but so did every rich person in America. The thing is most of them didn’t rent their house to Mussolini, host parties for Nazis and mobsters, or marry members of the Italian Fascist government.

It didn’t help that she kept doing stupid things: when Italian actor Tullio Carminati was briefly detained at Ellis Island she sent him a cake with a knife in it. It was a gag, but she was only one who found it funny. The FBI so completely missed the joke that they put her under surveillance and suggested she be detained as a foreign agent.

In March 1941 she decided to play it safe and decamped to Mexico City for the duration. She figured she could just take over the social scene, like she had in Beverly Hills a decade earlier, but didn’t count on the fact that the queen of Mexico City’s expat social scene, Mrs. Wallace Payne Moats, hated her guts. She was constantly snubbed and eventually forced to import friends from Europe: in this case, the exiled King Carol II of Rumania and his mistress, Magda Lupescu.

Politics wasn’t the only motivation for her move, though. She was also trying to keep costs down. Her financial situation was getting dire. Her inheritance was almost entirely gone. The Villa Madama was had been seized by the Italian government, which had confiscated everything except for one small cottage for official use and offered only pittance in return. Most of her remaining assets were in Italian banks, which were kind of hard to transact with given that there was a war on even if Mussolini hadn’t outlawed taking lire out of the country.

The Countess had always been addicted to get-rich-quick schemes, and as her bank account dwindled she placed her bets on longer and longer long shots. The most disastrous was a vitamin oil factory run by con artist Fred Angevine, which turned out didn’t actually exist — Angevine had just been taking her money and sending her fake account statements that she never followed up on.

Her only reliable source of income was her mansion in Beverly Hills, which she rented out to other rich folks. Elsa Maxwell was always happy to use it for a party venue, as was Evalyn Walsh McLean, owner of the Hope Diamond.

The Countess Dorothy Dentice di Frasso who returned to the United States after the end of World War II was a very different Countess. Her money was almost entirely gone; she had her furs and jewels and property but that was about it. She had few friends, as most of her acquaintances had abandoned her when she started cavorting around with mobsters and war criminals. She was a widow too; Carlo had died in February 1945 as the Allies swept through Italy.

In her mind, though, she still had the magic. In January 1946 she approached Bugsy Siegel and offered to sell some of her jewels to help finance the completion of the Flamingo Hotel & Casino. Siegel turned down her offer, which most mob historians seem to regard as a romantic gesture, a gallant attempt to keep his ex-lover from wasting her dwindling assets on a doomed venture. It seems just as likely, though, that Siegel was trying to avoid being sucked back into the Countess’s suffocating embrace.

Siegel was gunned down by persons unknown in June 1947. Everyone was suddenly reminded of his long-time relationship with the Countess and she decided it would be best to get out of town. She sold her mansion to conductor José Iturbi, took an extended sabbatical in Italy, and eventually relocated to Palm Beach, Florida.

In 1947 she was able to reclaim some of her money and property that had been confiscated during the war, though the Italian government kept the Villa Madama. It was too little, too late. She had lost too much money on disastrous business ventures, and couldn’t curb her spendings. By the end of the decade she was almost completely out of liquid assets and was forced to live off a trickle of money coming in from a trust set up decades earlier by her father.

Gone were the days of million dollar mansions and hosting extravagant parties. In her own words, she was forced to “live like a turnip.” She somehow managed to get her kicks in less expensive ways, like trying to get her revenge on Gary Cooper by encouraging him to divorce Veronica Balfe and marry Patricia Neal instead, or trying to beat the crap out of crime reporter Michael Stern in the lobby of the Excelsior Hotel in Rome when he started asking impertinent questions about her relationship with Bugsy Siegel.

She could never turn down a good party, though. When her good friend Marlene Dietrich opened a one-woman show at the Sands in January 1954, well, the Countess just had to be there. (Astoundingly, she had never been to Las Vegas before, even though her lover had helped build it up from nothing.) She had a blast. She was joined by dear friends like Cary Grant, Clifton Webb, and Elsa Maxwell. Dietrich was phenomenal, of course, and the afterparty was to die for.

Literally.

The festivities came to a screeching halt when the Countess collapsed outside the ladies’ room. Dietrich and Grant rushed to her side and forced her to swallow some of the nitro pills she had been popping all night like they were Tic Tacs. The Countess soon came around and explained she had a serious heart condition which meant she couldn’t drink alcohol or eat rich food… which she had been doing non-stop all day. She was surprisingly chipper about it, chirping, “You know, darlings, I am going to die.”

Her worried friends called her doctor back in Encino — there’s a come-down, Beverly Hills to Encino — scheduled an appointment for the next day and booked an overnight ticket on the Union Pacific Los Angeles Limited. Grant drove her to the train station, and Webb boarded the train to act as her guardian. There wasn’t much he could do, though. He went to wake the Countess in her sleeper compartment as the train pulled into Pomona, and discovered that she had died during the night. Her corpse was wearing thousands of dollars of furs and jewels.

It was January 4, 1954.

The Countess Dorothy Cadwell Taylor Grahame-White Dentice di Frasso was interred at the Taylor family plot in the Bronx. Grant and several of her friends accompanied the coffin back to New York and threw a wake where they toasted her menu all night. Grant wistfully remarked, “We did it because we remembered how much Dorothy hated being alone.”

There were problems with her will, of course. There was quite a bit of money left in the family trust, but Dorothy could not legally transfer her share to anyone else. Other than that she had about $20,000 in liquid assets and tens of thousands of dollars in jewelry and furs, some of which had gone missing. In the end her brother got $1, her maid Filomena Renzi got $25,000, and the remainder of the estate went to her niece Mary Taylor.

Final Thoughts

Those who knew the Countess di Frasso would always remember her as a gracious and giving hostess who loved excitement. If they were being honest, though, they would have to admit that they barely knew her.

She was a person with a million acquaintances, all of them shallow. During her life Barbara Hutton, Cary Grant, Clifton Webb, and Marlene Dietrich were her nearest and dearest friends. Constance Bennett was her business partner. She feuded with Kay Frances, Noel Coward, and Tallulah Bankhead. And yet her impact on their lives was so negligible that the Countess is barely mentioned in their biographies.

She had only one true friend, Elsa Maxwell, who described the Countess in her autobiography as “a very generous woman who craved adventure rather than getting old,” and praising her as a “great broncobuster of the banal, bathos, pathos and hypocrisy that makes up what we call modern society.” That was it, though. To everyone else she was a punchline, a joke, someone to namecheck when you were telling a story about the weird wild parties of old Hollywood.

In the end, the Countess’s story wound up being shaped by the biographers of three very different men, none of whom liked her all that much. To Claude Grahame-White’s biographers she was a silly, fatuous girl who kept distracting the great man from the very important business of running a failing aviation company. To Gary Cooper’s biographers she was a old fool who kept complicating his relationships because she was too lovestruck and obtuse to pick up obvious signals. To Bugsy Siegel’s biographers she was nothing more than an easily exploitable mark who quickly outlived her usefulness.

Here’s the thing: it’s hard to argue that they’re wrong. Dorothy was so many things during her life: vivacious and fun; cruel and uncaring; pretty and witty; vain and shallow; cultured and sophisticated; superficial and intellectually incurious; strong-willed; easily manipulated; generous and giving; petty and vindictive; loving and tender; incapable of forming true friendships. If you’re going to take a random slice of her life it’s a crapshoot which version of Dorothy you’re going to get: a fun-loving Fascist, a generous and gullible socialite, a tender but vindictive lover. It’s just dumb luck the only slices of her life that posterity cares about just happen to be particularly unflattering.

Hopefully this episode will help you remember a slightly different Dorothy: a dark-haired beauty with eyes full of fun who loved life, and was often disappointed when it didn’t love her back the same way.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Connections

When Dorothy Taylor joked that she and Claude Grahame-White were engaged, the pair were brunching with Claude’s friends Lionel and Alan Mander. Lionel would later move to the United States, change his name to “Miles Mander,” and become a movie star. Miles played a scheming crime boss in Sherlock Holmes film “The Pearl of Death” (1944) but was upstaged by his hideous minion, played by acromegalic actor Rondo Hatton (“Monster without a Mask”). (For that matter, Lupe Vélez was the star of “Hell Harbor”, Rondo’s first movie.)

The Graham-Whites’ European friends included Russian Ballerina Anna Pavlova. Anna is little remembered today, though the meringue-based desert that bears her name is as delicious as ever (“You Are Who You Eat”).

Dorothy’s rival for Graham-White’s affections, Ethel Levey, made her theatrical debut in Charles H. Hoyt’s musical comedy “A Milk-White Flag.” One of Hoyt’s earlier musicals, “A Trip to Chinatown” was a star vehicle for actress/fraudster Laura Biggar (“Pleadings from Asbury Park”).

Gary Cooper was encouraged to seek out the Countess di Frasso by her friend Walter Wanger. Wanger is probably most famous for shooting his wife’s agent in the balls, but before that he produced a string of hits that included 1943’s “Arabian Knights” starring Sabu, Maria Montez, Shemp Howard, and “The Venezuelan Volcano” Burnu Acquanetta (“Burning Fire, Deep Water”).

Cooper starred as Billy Mitchell in “The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell” (1955), where the former general was put on trial after going on an angry rant denouncing his superiors. One of the incidents that prompted Mitchell’s tirade was the crash of the rigid airship the USS Shenandoah, which killed his good friend Capt. Zachary Lansdowne (“Air Crash Museum”).

During her time in Hollywood, the Countess occasionally frequented the bar at the Garden of Allah hotel (“The Garden of Oblivion”) where she palled around with regulars like William Powell, Cary Grant, John Farrow, and David Niven. (She avoided Tallulah Bankhead, though.)

Through Bugsy Siegel, the Countess has ties to other members of the National Crime Syndicate including Owney Madden and Abe “Kid Twist” Reles (peripheral figures in the disappearance of Judge Crater, from “Call Your Office”); Meyer Lansky (a known associate of Florida real estate developer Bebe Rebozo, from “Be My Bebe”); Santo Trafficante (also an associate of Robozo, and probably responsible for the disappearance of Key West fire chief Bum Farto, from “With Both Hands”), and “Davie” Berman (one of the one of the Jewish Mafiosos who ran “American Hitler” William Dudley Pelley and his fascist Silver Legion out of Minnesota, from “Seven Minutes in Heaven”).

Many people have sought the Treasure of Lima over the years, including British racecar driver Sir Malcolm Campbell. During WWII Campbell became a member of Combined Operations HQ, a dumping ground for eccentrics and weirdos and geniuses who didn’t fit in anywhere else. One of those genius weirdos was Geoffrey Pyke, who conceived of Project Habakkuk, a wild plan to build an aircraft carrier out of ice and sawdust (“Wonder Marvelously”).

Also, not a connection to us, but if you’d like to learn more about the Treasure of Lima and Cocos Island you should check out The Curiosity of a Child episode “Tales of Treasure”.

Peru did eventually win its independence, though Spain refused to recognize it. That eventually led to the Chincha Islands War in 1865. One of the participants in the war was artist James McNeill Whistler (“Crepuscule in Blood and Guts”), though truth be told his participation was very limited.

If you want more stories of maroons being rescued from remote islands, there’s always the tale of James Francis O’Connell, the “Tattooed Irishman” of Pohnpei (“Liminal Space”).

Others who attempted to sell projects of dubious value to Mussolini include librarian and utopian Paul Otlet, who hoped Il Duce would back his proposed World City (“Steampunk Google and the World City”).

Sources

- Anile, Albert. “Mary and the Moor: The Precious Memories of Orson Welles’s Secretary from the Set of Othello.” Film History, Volume 27, Number 2 (2015).

- Arce, Hector. Gary Cooper: An Intimate Biography. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1979.

- Bach, Steven. Marlene Dietrich: Life and Legend. New York: William Morrow, 2002.

- Collins, Amy Fine. “The Man Hollywood Trusted.” Vanity Fair (April 2001).

- Cukor, George. The Women. 1939.

- Elet, Yvonne. Architectural Invention in Renaissance Rome: Artists, Humanists, and the Planning of Raphael’s Villa Madama. London: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Eyman, Scott. Cary Grant: A Brilliant Disguise. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020.

- Gragg, Larry Dale. “Gangster.” History Today, June 2015.

- Gragg, Larry Dale. Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel: The Gangster, the Flamingo, and the Making of Modern Las Vegas. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2015.

- Higham, Charles and Moseley, Roy. Cary Grant: The Lonely Heart. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1989.

- Hobart, Christy. “Elsie in Amber.” House and Garden, May 2007.

- Jennings, Dean Southern. We Only Kill Each Other: The Life and Bad Times of Bugsy Siegel. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1967.

- Kear, Lynn and Rossman, John. Kay Francis: A Passionate Life and Career. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2015.

- Kellow, Brian. The Bennetts: An Acting Family. Louisville, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 2004.

- Le Poidevin, Richard and Le Poidevin, Antoine. “Tales of Treasure: Cocos Island, the Centurion, and a Hermit.” The Curiosity of a Child. https://curiosityofachild.podbean.com/e/48-%f0%9f%aa-tales-of-treasure-cocos-island-the-centurion-and-a-hermit/ Accessed 7/21/2023.

- Levinson, Barry. Bugsy. 1991.

- Mandell, Lisa Johnson. “The real countess of Beverly Hills estate is listed at last.” At Home In Hollywood. https://athomeinhollywood.com/2016/06/02/real-countess-of-beverly-hills/ Accessed 8/30/2022.

- Maxwell, Elsa. I Married the World. Melbourne: William Heinemann, 1955.

- Meares, Hadley. “Meet the Mysterious Socialites Behind LA’s Wildest New Party House.” Curbed, 23 Mar 2016. https://la.curbed.com/2016/3/23/11286538/yotta-life-party-mansion Accessed 8/30/2022.

- Meyers, Jeffrey. Gary Cooper: American Hero. New York: William Morris, 1998.

- Niven, David. Bring on the Empty Horses. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1975.

- Preston, Douglas. The Lost City of the Monkey God. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2017.

- Shnayerson, Michael. Busy Siegel: The Dark Side of the American Dream. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2021.

- Stadiem, William. Jet Set: The People, the Planes, the Glamour and the Romance in Aviation’s Glory Years. New York: Ballantine Books, 2014.

- Stern, Michael. No Innocence Abroad. New York: Random House, 1947.

- Turnbull, Martin. “Hollywood Places – U to Z.” martinturnbull.com https://martinturnbull.com/hollywood-places/places-u-to-z/ Accessed 8/30/2022.

- Way, Jane Ellen. Cooper’s Women. New York: Prentice Hall, 1998.

- Wallace, Graham. Claude Grahame-White: A Biography. London: Putnam, 1960.

- Walker, Frank. The Scandalous Freddie McEvoy. Sydney: Hachette Australia, 2018.

- Webb, Clifton and Smith, David L. Sitting Pretty: The Life and Times of Clifton Webb. Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi, 2011.

- “Countess Dentice di Frasso.” Meher Baba’s Life and Travels. https://www.meherbabatravels.com/personalities/countess-dentice-di-frasso/ Accessed 8/30/2022.

- “Countess di Frasso, the American Heiress Dorothy Taylor, in Her Youth.” Playground to the Stars. http://www.playgroundtothestars.com/2013/12/countess-di-frasso-the-american-heiress-dorothy-taylor-in-her-youth/ Accessed 8/30/2022.

- “The Countess Dorothy di Frasso.” Tweedland. http://tweedlandthegentlemansclub.blogspot.com/2013/07/the-countess-dorothy-di-frasso.html Accessed 8/30/2022.

- “Dorothy Before Being DiFrassonized! British Ace’s Wife, Mrs Claude Grahame-White!” The Esoteric Curiosa. http://theesotericcuriosa.blogspot.com/2011/09/blog-post_25.html Accessed 8/30/2022.

- “Dorothy Caldwell Taylor Dentice di Frasso.” Find A Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/177989689/dorothy-cadwell-dentice_di_frasso Accessed 7/29/2022.

- “Explosive is more powerful than T.N.T.” Popular Mechanics, Volume 50, Number 3 (September 1928).

- “Metha Nelson accusers.” Calisphere. https://calisphere.org/item/ad62d768fecbe065921aa0c80f4ae9e0 Accessed 7/29/2022.

- “Milestones.” Time, Volume 1, Number 19 (Jul 9, 1923).

- “People.” Time, Volume 63, Number 4 (January 25, 1954).