The Sea King

the last Confederate ship

At the start of the American Civil War, the U.S. Army was in a bad place.

To be fair, it would have been hard for the Army to hold on to officers committed to the heinous causes of slavery and white supremacy, and even harder for it to hold on to forts in hostile Southern territory. It also didn’t help that James Buchanan’s Secretary of War, John Buchanan Floyd, had been treasonously diverting materiel to Southern armories for years.

In comparison, the U.S. Navy was in a very good place. Don’t get me wrong, the defection rate for naval officers was about the same as it was for army officers, but the Navy managed to hang on to most of the fleet. This naval superiority made it possible for Lincoln to establish a blockade of Southern ports and cripple the Confederate economy.

As a result, the Confederate Navy was in a bad place. Southern ports and shipbuilding facilities lagged far behind their Northern counterparts, which didn’t matter much because the blockade made it impossible to get raw materials. They had to make do with barges and gunboats and rams and the occasional captured Union vessel.

To shift the balance of power, the Confederate Navy would have to acquire new ships from somewhere else. It immediately turned to Great Britain, the Confederacy’s largest trading partner and arguably the best shipbuilders in the world. There was only one problem: Great Britain was ostensibly a neutral party to the Civil War, and according to its own laws British companies weren’t allowed to sell armaments to any of the belligerents.

British shipbuilders were more than happy to ignore the law, but they were being watched like a hawk by Ambassador Charles Francis Adams. For four long years Adams made damn sure the British actually stuck to the terms of their professed neutrality. Whenever the rebels tried to purchase war materiel, Adams would raise a fuss and the Crown would step in to shut things down.

Even so, Confederate agent James Dunwoody Bulloch managed to acquire two sloops in 1862, and had them retrofitted into… well, not real warships, but “sloops-of-war” that could still do some damage. The CSS Alabama and the CSS Florida were “commerce raiders” (i.e., privateers) who preyed on American shipping with the goals of crippling trade, diverting ships from the blockade, and destroying public morale. For two years the two privateers went on a rampage, capturing and sinking more than a hundred Yankee merchant vessels.

Of course, merchant vessels aren’t exactly known for being heavily armed. Whenever the commerce raiders encountered actual encountered Union warships they fared very badly. On October 7, 1863 the Florida was docked at the Brazilian port of Bahia when she was rammed in the middle of the night by the USS Wachussett, which captured the crew and towed her back to Chesapeake Bay. Eight months later on June 19, 1864 the Alabama was finally cornered by the USS Kearsage at the French port of Cherbourg, and sunk after a brief engagement in international waters.

That left Bulloch with no navy. His recent attempts to acquire two ironclad “rams” had been foiled by Adams, so he switched his goal from building new ships to acquiring existing ships.

In October 1864 Bulloch finally acquired a new vessel, the Sea King, from Liverpudlian merchant Richard Wright. Wright was sympathetic to the Southern cause, mostly because he was heavily invested in cotton. The Sea King was an “extreme clipper” — excuse me, an ***EXTREME CLIPPER!!!*** — designed for making the tea run from Canton to London at high speed. She was a sizable ship, 230′ long and displacing about 1,000 tons, propelled by the one-two punch of a traditional sail augmented by a 250 horsepower steam engine. She could make make eight knots in a dead calm and sixteen knots with favorable winds.

Bulloch’s purchase wasn’t a secret for very long. Adams desperately tried to stop the Confederates from taking control of their new vessel, assigning the USS Niagara and the USS Sacramento to seize her in international waters. Alas, they wound up mistakenly detaining a Spanish vessel while the Sea King steamed merrily out of port, ostensibly on the first leg of a two year trading voyage.

The CSS Shenandoah

A week later on October 20th, the Sea King rendezvoused with a supply ship, the Laurel, in international waters near Madeira. She took on a full load of coal — along with some three dozen Confederate naval officers and seamen.

Their first order of business was to transfer the ship’s registry. This was a mere formality, since money had already exchanged hands in Britain, but completing the transaction on the high seas allowed Wright to avoid the consequences of violating British neutrality laws. The ship was rechristened the CSS Shenandoah and placed under the command of Captain James Iredell Waddell.

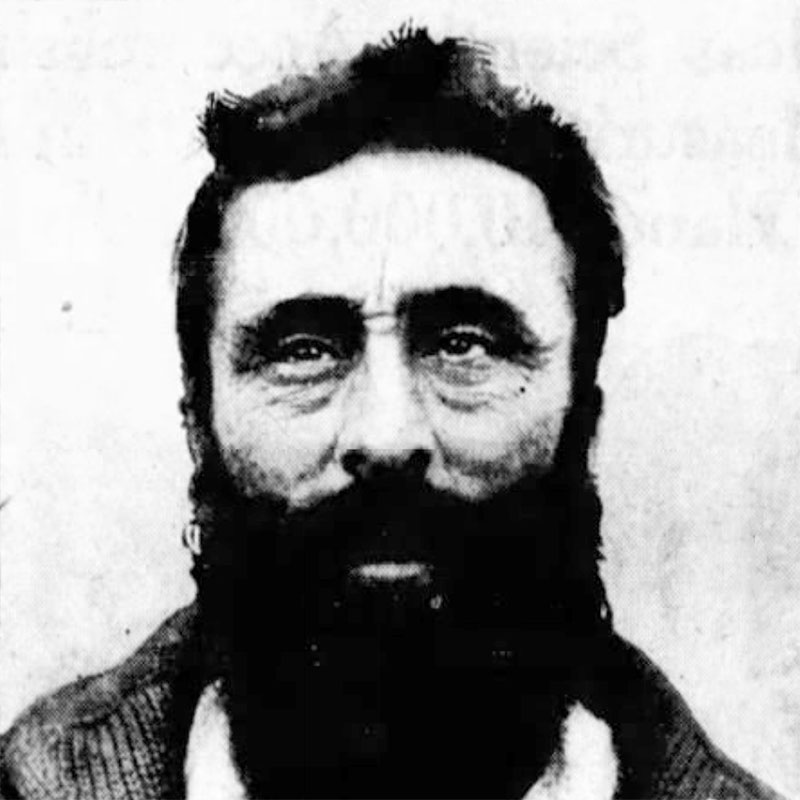

Captain Waddell was an experienced officer with over twenty years of undistinguished service. The only real highlight of his career was how it had ended: he jumped ship on St. Helena after resigning his commission, and hitchhiked his way back to Maryland to pledge his loyalty to the Confederacy. His devotion to the Southern cause was only deepened by his personal tribulations — namely, his fruitless attempts to get the U.S. Navy to make good on his back wages, which they were refusing to pay out over a mere technicality like “treason.”

Waddell was hardly anyone’s first choice to command a commerce raider. That would have been the dashing Raphael Semmes, former captain of the Alabama, but he was still recovering from injuries received in battle. Waddell just happened to be next in line, a captain without a commission, since he was supposed to have skippered one of the ironclad rams that had been seized. The end result was a profound mismatch of captain and vessel. Waddell was a methodical rule-follower, the perfect skipper for a commercial steamer on a tight schedule, but hardly bold or decisive enough to command a privateering vessel where every day would present him with difficult choices.

Difficult choices which began immediately.

The Shenandoah needed at least 60 hands to be considered “fully crewed” and should ideally have carried a full complement of 150 to ensure operation at peak efficiency. The thirty-odd Confederates on board now barely comprised a skeleton crew. Captain Waddell tried to solve the manpower crisis by enticing the Sea King‘s former crew to stay on under the new management. He offered a generous £10 signing bonus and a salary of £4/month. They turned Waddell down flat, since they had been looking forward to an easy voyage and were not exactly eager to be dragged into a foreign war. The captain responded by upping his offer to a £15 bonus and £7/month.

That convinced some of the British sailors to enlist. But only nine of them.

That brought the Shenandoah‘s crew complement up to 43: 9 British volunteers, 10 veterans of the CSS Alabama who had been left behind in France, and 23 officers. The ship was still some 17 hands shy of being fully crewed. What’s worse, it also boasted a 1.2:1 ratio of officers to enlisted men. Anyone who’s ever worked in a middle management-heavy office can tell you that’s not an ideal situation.

For now, though, the crew had their hands full retrofitting the Shenandoah into a proper warship. Or, I should say, the ship’s carpenter had his hands full, as there was no one else on board capable of assisting him. For several days he worked non-stop cutting gun ports, reinforcing bulwarks, and turning the extreme clipper into a… clipper-of-war? That doesn’t sound right. The rest of the crew spent their time clearing the deck, setting up their depressingly spartan quarters, and staying out of his way.

During the retrofit, another major problem was discovered. While attempting to mount the ship’s mighty 32-pound Whitworth guns, First Officer William Conway Whittle noticed that they had forgotten to pack the gun tackles necessary to secure them. If the big guns were ever fired, recoil would propel them across the deck and through the hull. The ship wasn’t technically defenseless, mind you, as it was equipped with a pair of 12-pounders. Then again, since the primary use of the 12-pounders was to fire warning shots, the only ammunition they Confederates had for them were blanks.

This was hardly an auspicious start to the voyage of the CSS Shenandoah.

Faced with shortages of men and materiel, Capt. Waddell made his first decision: the Shenandoah would make for Tenerife, where she could stock up on supplies and do a little light recruiting on the side.

His officers immediately objected. The Laurel wasn’t due back in Liverpool until mid-November, which gave the Shenandoah a three week head start over any Yankee pursuers. A trip to Tenerife would cut that head start down to mere days. Unable to refute that logic, Waddell backed down and ordered the ship to bypass the Canary Islands and head south into the mid-Atlantic shipping lanes. With luck, he would stumble across a prize whose cowardly captain would surrender at the mere sight of the Confederate flag.

This was a sign of things to come. Without clear orders to follow, Waddell was horribly indecisive. He agonized over every decision, second-guessed himself, and did not stick to his guns when challenged. He was also conflict-averse, both in terms of interpersonal relationships and, y’know, actual naval battles. This seemed like mere prudence to the seasoned captain, but it seemed a lot like cowardice to his hot-headed junior officers, and especially to First Officer Whittle. Lieutenant Whittle began to openly challenge and undermine his captain at every turn… though he was always careful to stop just shy of outright insubordination.

For now, though, the ship made its way south. Once they were able to raise the anchor, that is. The skeleton crew had a bit of trouble with that at first.

On October 28th, the Shenandoah spotted a square-rigged barque and gave chase. It turned out to be nothing but trouble. The Mogul was an American ship — or at least, it had been until 1863, when its owners transferred the registry to a British firm. Commerce raiders were supposed to let neutral vessels pass unmolested. Yankee merchants knew that, though, and had been forging registries from neutral countries as a get-out-of-jail-free card for situations just like this. Captain Waddell suspected that was the case here, but if the registry was legitimate he would be needlessly antagonizing the British.

Reluctantly, Waddell let his prize go. The other officers were not happy, and started grumbling behind his back.

Two days later on October 30th, the Shenandoah chased down a second barque and found more problems. The Alina was actually American, but its cargo was not. The captain had papers proving that the $90,000 of railroad iron in the hold had been purchased by a British company building railroads in Buenos Aires. Captain Waddell had another hard choice to make. If he seized the Alina, he’d be antagonizing the British. If he let it go, he’d be antagonizing his officers and letting supplies he desperately needed slip away.

In the end he settled the matter with a technicality: the contracts carried by the captain were not notarized, and therefore not legally binding. The Confederates stripped the Alina of everything: the iron in the hold, pulleys and rope to make gun tackles, yards and yards of spare canvas sail, canned provisions, crockery, silverware, books, even the furniture from the captain’s quarters. And then they sunk her.

Seven of the Alina‘s twelve hands decided to sign on with the Shenandoah, bringing its crew complement up to 50. You may be wondering what could possibly convince a man to join forces with the privateers who have just destroyed his ship. What you need to remember is that the choice is between doing the same job you’ve already been doing, getting paid, and enjoying some degree of freedom; and getting clapped in irons, tossed in the brig, and rotting away below decks. It’s not exactly the hardest choice to make. You should also know that none of the seven defectors were American: three were French, and the others were German, Dutch, Swedish, and Malaysian. They really didn’t care who won the American Civil War.

The important thing, here, though, was that the Shenandoah now had proper gun tackles and was fully operational. Well, mostly operational. Clippers weren’t exactly built to carry cannon. The balance was so far off that if the gunners were ever called on to fire a proper broadside, the ship would flip over. Still, with the cannon properly secured, Captain Waddell could be more aggressive. Unfortunately, for the rest of the week every ship he caught was indisputably British and had to be let go.

The officers were disappointed, and many of them began to shirk their duties. It didn’t help that they thought these duties were beneath them — these were tasks that would have been handled by seamen had the ship been fully crewed. To try and shut that line of thinking down Captain Waddell decided to make an example of the biggest shirker, Lieutenant Francis Chew. When it came time for First Officer Whittle to mete out discipline, he objected. Whittle’s personal code of honor prohibited him from raising his hand to Southern gentlemen and fellow officers. Not that he was soft-hearted, mind you: he was all too happy to inflict out the most barbarous tortures to anyone who crossed him. In the end Waddell backed down, and once again wound up looking weak. He should have stood his ground. Chew was dangerously incompetent, and would cause all sorts of problems over the next several months.

At dusk on November 5th the Shenandoah gave chase to a schooner, which she caught just as dawn was breaking the following day. The Charter Oak was the fairest prize she’d caught so far, as American as American could be. And yet once again it presented a head-scratching dilemma. If Captain Waddell sunk the Charter Oak, he’d have to take on the passengers and crew as prisoners. Captain Samuel Gilman would have been easy enough to cope with, but his crew consisted of three Portuguese sailors who were obvious deserters from the Union Navy. The passengers were even worse, since they were all civilians and non-combatants: Gilman’s wife, widowed sister-in-law, and six-year old nephew. Waddell did not like the idea of having women and children on board, and he liked the idea of having deserters on board even less. The smart move would have been to bond the ship — essentially. forcing Captain Gilman to sign a contract to sit out the remainder of the war in a neutral port, and then reimburse the Confederacy for the value of his cargo after the conclusion of hostilities. Bonding the ship, though, meant that the Shenandoah would lose out on its cargo: 2,000 pounds of canned fruit, 600 pounds of canned lobster, and a 500 lb. hogshead of fresh ice.

It was Gilman who made up Waddell’s mind, insisting he had excellent insurance and could cope with the loss of his ship. The canned fruit and lobster were welcome addition to the Shenandoah‘s stores, but the ice proved to be more trouble than it was worth. In the process of retrieving it they lost a launch when it drifted too close to the Shenandoah‘s propeller, and then after wrangling the barrel on board they discovered the ice had already melted. It seemed like a metaphor for the voyage so far.

On November 7th, the Shenandoah ran down another barque, the De Godfrey, bound for Valparaiso with a hold full of pork, beef, tobacco and lumber. Alas, the supplies Captain Waddell desperately needed, the meat and tobacco, were buried beneath 40,000 feet of lumber that would take an entire day to move. Waddell had to settle for grabbing 40 easily accessible barrels of salt beef and then putting the rest to the torch. At least the burning meat and tobacco gave off a lovely lingering smell.

The De Godfrey‘s captain and most of his crew willingly enlisted with the Shenandoah. One sailor, though, refused: John M. Williams, the cook. This was a problem, because the Shenandoah desperately needed a cook. Fortunately for the Confederates, Williams was a free black man so they just enslaved him and threatened to torture him to death when he refused to work. Williams reluctantly complied, though that didn’t stop Lieutenant Whittle from meting out harsh discipline whenever he felt the cook wasn’t showing enough gratitude to his white saviors. (What a swell guy.)

The ship was now fully crewed, if just barely, but was now facing a different problem demographic problem: there were forty prisoners crammed into the hold. On November 9th, Captain Waddell arranged to have eight of them transferred to a Danish ship, the Anna Jane, in exchange for a spare chronometer and some provisions. The officers, lead by Lieutenant Whittle, once again objected, arguing that the released prisoners would spread the word of their existence and eliminate their one real advantage: surprise. It was a good point, but officers didn’t seem to understand that according to the rules of war prisoners had to be fed and cared for. Waddell knew that the Shenandoah‘s stores were low, and the ship was only going to take on more prisoners over the next few weeks. If their numbers grew too large, he was taking on the risk that they might band together and seize control of the vessel.

The Gilmans were allowed to remain on board. The officers once again objected, saying that if they were going to get rid of any of prisoners the Gilmans should be first in line. They probably had a point: the unctuous Captain Gilman was nothing but trouble. Captain Waddell had his reasons, though. Gilman’s sister-in-law and her son had been bound for California, and Waddell felt it was his duty as a Southern gentleman to see a widow through to her final destination, or at least get her on a ship headed in the right direction. It was honorable, I guess? Though as we will see later the Southern ideals of honor could be very mutable.

The next day, the Shenandoah came across the weirdest ship she’d ever seen, the Susan out of New York. At first glance the Susan looked like a side wheel steamer, but the side wheel wasn’t actually moving the ship. It was providing power for the bilge pump. The system didn’t work very well, and as a result the Susan was on the verge of sinking to the bottom of the Atlantic and taking its cargo of coal with it. The crew was eager to jump ship and sign on with another captain, so the Shenandoah‘s ranks swelled once more to the tune of three hands and a dog. Even the ship’s captain tried to join up, but Waddell refused because he was a Jew.

The next day they ran down another ship, the Kate Prince of New Jersey, with a load of Cardiff coal bound for Bahia. While the ship’s captain presented Waddell with papers proving the ship’s cargo was owned by a British firm, his pretty young wife took Lieutenant Sidney Lee aside and explained that while her husband was a dirty Yankee, she and the 21 man crew were all Confederate sympathizers and very eager to do their part for the cause. The junior officers suddenly became very, very eager to burn the Kate Prince. Even more eager than usual, I should clarify — they wanted to burn every ship they ran into, to hell with the consequences. This shows why they were only officers and Waddell was the captain. The Kate Prince‘s papers were duly notarized, unlike the Alina‘s, and Waddell had no choice but to let her go. On the plus side, he also used it as a chance to pass off his remaining prisoners on someone else. Including the Gilmans this time.

Later that day they ran down the Adelaide, transporting a cargo of flour from New York to Rio. It was flying an Argentine flag, but Captain Waddell knew immediately that the transfer was fraudulent. The raiding party stole everything that wasn’t tied down, smashed furniture and cabins to pieces, and poured kerosene all over the deck. They were just about to light the match when a lieutenant discovered papers proving that the ship’s real owner was a Southern smuggler who had somehow figured how to get around the Union blockade. Waddell hastily called the burning off and had the cargo re-loaded while he figured out how to deal with yet another tricky problem. The damage to the Adelaide was severe — if she encountered a Union vessel, the fact that she had been stopped by a Confederate raider would be obvious, and it would be just as obvious that the privateers had not sunk or bonded her. The entire smuggling operation would be exposed. In the end, he bonded the ship. It was the best he could do. It gave its captain a get-out-of-jail free card, and transferred all the heat to Waddell for having illegally bonded a neutral vessel.

Third times a charm, though. On November 13th they caught the Lizzie M. Stacey out of Boston, bound for the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii). She was as fair a prize as they could hope for, and the crew set her ablaze with joy. Only to then panic as the wind changed and the burning boat started drifting their way. Emergency evasive maneuvers had to be taken.

For the next three weeks, the ship sailed along the coast of Brazil, and then turned east to cross the South Atlantic.

The officers were, as usual, not happy. They had been at sea for six weeks now and had seen precious little in the way of action. They’d stopped eight ships and had to let three of them go. Of their five prizes, one was of questionable legitimacy and the others were small potatoes at best. In the last three weeks they hadn’t stopped a single ship. In the meantime word of the Shenandoah‘s conversion had finally reached the American government, and they were now being actively hunted by Union warships. The crew took their frustrations out in the only way they could, by writing nasty letters in their diaries about the captain.

No one seemed to appreciate that Waddell was only making the best out of a bad situation. For six weeks he had managed to cope with insubordinate officers, a short-staffed crew, and a lack of provisions. Yes, he’d had some difficulties navigating the rules of war, but you can’t really blame him for that — no wait, actually you can.

On December 4th, the Shenandoah‘s luck finally turned, or so it seemed. Near Tristan de Cunha she encountered the Yankee whaler Edward, which was so engrossed in the process of rendering a captured whale that the Shenandoah was able to sneak up alongside without being noticed and finally start her long-hidden mission.

Waddell’s secret orders were to cripple the Northern whaling industry. Now, at first this may seem odd, since whaling had peaked in 1853 and had been in near-constant decline ever since thanks to the over-harvesting of whale fisheries, the invention of kerosene, and the discovery of oil in Pennsylvania. In the late stages of the war, though, the industry had rebounded. With whalers calling it quits in droves, whale oil and whalebone became scarce again, driving up the prices and making the industry commercially viable once more. It was only a temporary rebound, since the influx of new whalers wound up shifting the equilibrium point again, but that was in the future. It was 1864 and whaling was back, baby!

The Edward was a pretty little prize, at least. There was no whale oil to be had, but Waddell was happy to confiscate its ample stores: 200 barrels of beef and salt pork, ship’s biscuit to last for months, and even luxuries like tobacco, soap, butter, flour, and clothes. The captain dropped the whalers off at nearby Tristan de Cunha and turned east towards Cape Town. Unfortunately he also had to drop off most of the provisions he’d just looted, too. The British governor had initially refused to take them, since it would be a violation of British neutrality, and the provisions were a bribe.

Victoria

Three days later the ship started to make a strange sound. It turned out the brass sleeve around the propeller had cracked, and the damage was too severe to be fixed at sea. The crew also noticed that this was a pre-existing issue that had been addressed with temporary repairs on at least one occasion. It seemed like Wright had sold Bulloch a lemon.

Captain Waddell had to make another tough choice. The easy move would be to keep heading for Cape Town and receive repairs there. On other hand, that would be first place any pursuing Union vessels would be looking for them. Waddell made the counter-intuitive move to bypass Cape Town, make his way across the entire Indian Ocean, and put in at Melbourne for repairs. Had Waddell put in at Cape Town he would have almost certainly been sunk by the USS Iroquois, which was only a few days behind them. He had made the right move, but for the wrong reason. The captain was less concerned about Union pursuit than he was about making a pre-planned rendezvous with a mail steamer in Melbourne that he could use to send letters to his wife and children.

To avoid pursuers the ship flirted with the weather at perilous Antarctic latitudes, where it was lashed by rough swells, cold winds, and ice. It worked, though. For four weeks they didn’t see a single soul.

That changed on December 29th. As the weather let up the Shenandoah spotted another American vessel, the Delphine, and quickly ran her down. It was a fair prize with a hold full of rice polishing machinery headed for Burma. The ship’s timid captain, William G. Nichols, tried to convince the Confederates to bond instead of burn his ship. He claimed that his wife was on death’s door and that she could not be moved or she would die. The Shenandoah‘s doctor made a house call and found Mrs. Nichols to be the picture of health. More than that, actually: she was a knockout. He also realized she was a vicious, controlling mean girl who would test the limits of the crew’s patience and gallantry.

Plundering the vessel was put on hold when Lillias Pendleton Nichols began barking orders at the privateers, ordering them to fill two whaleboats with her personal possessions and transfer them to the the Shenandoah. Then she commandeered the captain’s cabin without asking first, demanded that the “pirate chief” set her ashore immediately, and slammed the door in Waddell’s face.

Things only got worse over the next month. Lillias Nichols belittled her husband William at every turn, and flirted with the Confederate officers to make him jealous. In their diaries, Waddell and Whittle expressed sympathy for poor henpecked Captain Nichols. The two of them together could barely contain his wife, who was constantly barking orders at the crew and acting like she owned the place.

Whittle only managed to silence her once. While unloading her possessions, he found a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in her library and threw it into the sea. Mrs. Nichols responded by screaming, “If I had been in command, you would never have taken the Delphine!” and stomping into her cabin. Waddell fared no better than his first officer. When the crew stopped at the remote Île Saint-Paul on January 2nd to barter for fish, the captain announced he would be complying with Mrs. Nichols’ request and putting her ashore. It was a joke, but Lillias panicked and locked herself in the cabin until the Shenandoah was safely back at sea.

That was more or less it for another month. They stopped another ship, the Nimrod, which had been legitimately transferred to a British firm, and failed to run down another clipper, the David Brown.

On January 25th, 1865 the CSS Shenandoah finally arrived at the port of Melbourne. The harbor pilot who came over first thought he was boarding the Royal Standard, which was due in that day, but quickly realized he had boarded the notorious Confederate raider. In awed tones he told the crew, “You have a great many friends in Melbourne.” As the Shenandoah steamed triumphantly into Port Philip Bay proudly flying the “stainless banner,” Yankee ships began hastily hauling down Old Glory and raising other flags.

Immediately upon docking, Waddell wrote a letter to Sir Charles Darling, the Governor of Victoria, requesting permission to make repairs to the propeller; take on a full load of coal, along with ammunition and provisions; and offload his prisoners. According the conditions of British neutrality, Darling’s answer should have been easy: hell no. Belligerent vessels allowed to spend only one day in port, unless delayed by weather; were only allowed to take on enough provisions to get them to the next neutral port; and were certainly not allowed to to dump their prisoners on Her Majesty.

Waddell had a ready-made answer to the last problem: he just emptied the brig the instant the ship docked. When authorities called him out on it, he claimed that the prisoners had been released without his knowledge or permission, which was a total lie. He had, in fact, made the parolees sign non-disclosure agreements pledging them to silence about their time on the Shenandoah. Lest you think that lying was a violation of Waddell’s honor a Southern gentlemen, remember, all’s fair in love and war. <sarcasm>I’m sure Waddell would have extended the same courtesy to lies made by, say, Union captains.</sarcasm>

On her departure, Lillias Nichols told the Confederates that she was much obliged by their hospitality and she hoped that they would be sent to the bottom of the sea. Then she marched her henpecked husband and the crew of the Delphine straight to the office of American consul William Blanchard, tore up her NDA, and shared everything she knew. Which was a lot. Apparently her flirting had been a cover for some light spying.

Blanchard immediately cabled Ambassador Adams in London to let him know the Shenandoah had arrived, then cabled the U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong asking for them to send a warship to Melbourne immediately. Then he wrote his own letter to Governor Darling, first arguing that because the Shenandoah had not set into any Confederate ports it had not been “naturalized” and was therefore a stateless pirate; and then arguing that even if it wasn’t, it was still a belligerent vessel and should be cast out of port by the end of the day.

There was only one problem: Sir Charles Henry Darling was total crap. Terry Smyth’s Australian Confederates describes him not only as “a classic example of the triumph of nepotism over merit” but also as “neither the first nor the last gormless English aristocrat to be appointed governor of a British colony.” Most of his decisions were actually made by Minister of Justice Archibald Michie and Attorney General George Higinbotham, both of whom were open Confederate sympathizers. Their argument was that since the Shenandoah would be receiving repairs in a private drydock and not a government facility, neutrality rules did not apply. It was an interpretation that couldn’t stand up to even the most casual reading of the neutrality acts, but the decision would have to be contested in the colonial legislature and the courts. That bought the Confederates what they really needed, time.

Realizing he had been outmaneuvered, Blanchard published notices offering $100 and a pardon to any member of the Shenandoah‘s crew willing to desert. He needn’t have bothered. Most of the crew had jumped ship the first chance the got. It turns out that the loyalties of impressed sailors are not that deep. Who knew?

Waddell had little difficulty recruiting new crewmen, because most Australians were Confederate sympathazers. Why? Well, being British, they always enjoyed some shadenfreude whenever someone stuck it to the United States. The Australian colonies were also only a generation removed from being penal colonies, and were developing a fascination with rebels and outlaws and rule breakers. Victoria, in particular, was only a decade removed from the 1854 Eureka Rebellion in the gold fields of Ballarat, and was in the process of mythologizing that.

There was also the matter of commerce. Australians were rooting for the Civil War to last as long as possible because the interruption of the Southern cotton trade was a boon to their domestic cotton plantations. Plantations where most of the work were being done by “blackbirds” — Pacific islanders kidnapped by pirates and forced into slavery.

So yeah. There was definitely some kinship there.

To recruit, Waddell took out coded ads in the Melbourne papers, offering wages of £6/month with a £8 signing bonus. It apparently worked. A few days later John Williams, the black cook from the De Godfrey who had been enslaved, escaped from the Shenandoah and made his way to the American consulate. He swore out affidavits saying that he had been replaced as cook by a white man named Charley, that Charley had come aboard in Melbourne, and that some two dozen other crewmen had also joined the ship’s company at the same time. His testimony was corroborated by other deserters.

This was all William Blanchard needed. He made a formal complaint to the authorities that the Shenandoah was in open violation of the Foreign Enlistment Act. Governor Darling surprised everyone by finally showing some spine and ordering that work on the Shenandoah stop until this “Charley” could be located and arrested.

The police made a polite attempt to search the vessel which was turned away by Lieutenant Grimball, the officer-in-charge. They returned in force, and this time they were turned away by Captain Waddell, who refused to let a foreign military force onto his vessel. Instead, he graciously had his master-at-arms conduct a search of the ship which, surprise surprise, found no one. Then he filed a counter-complaint, protesting that Blanchard was inducing his crew to desert and conveniently leaving out the fact that the “deserters” had been impressed on the high seas.

While this little drama was playing out, the Confederates were the talk of the town. The Shenandoah became a huge tourist attraction, drawing hundreds of gawkers, to the point where the shipwrights started charging sixpence apiece a peek. The crew were invited to bars, hotels, and the opera, where they vied for the attention of Melbourne’s lovely young ladies. The captain and his officers were even invited to banquet at the extremely exclusive Melbourne Club and taken on a guided tour of the gold mines of Ballarat.

The crew also took to brawling with visiting Yankee merchants in town over the most trivial insults. One of these bar fights involved broken bottles, stabbings, and even an exchange of gunfire. The Yankees weren’t gong to take that lying down, and the crew of the merchantman Mustang managed to attach an improvised explosive device containing 250 lbs. of gunpowder to the hull of the Shenandoah. It was a dud, but it was a good sign to Captain Waddell that he should get the hell out of town as soon as the repairs were complete.

As repairs wound down the Melbourne police began watching the Shenandoah like a hawk, looking to head off any violations of the Foreign Enlistment Act. On February 15th they intercepted a launch leaving the ship in the middle of the night with four local men on board. One of those neb was Charley (real name James Davison). No one could explain how they came to be on board. Especially not Waddell, who had given his word as a Confederate officer and a Southern gentleman that there were no locals on board.

Two days later, the Shenandoah took on a full load of coal and steamed out of port. Once it was safely in international waters, something miraculous happened. Forty-two able-bodied men materialized out of nowhere, assembled on the deck, and volunteered to join the crew. This more than made up for everyone who had deserted in Melbourne — though also meant that the Confederate raider was now primarily an Australian raider. In their memoirs and diaries, crew members professed complete ignorance as to where these men had come from. Waddell claimed to be to be utterly mystified. Whittle had the cheek to suggest it was a Yankee plot to frame them for violating the neutrality acts.

So much for Southern honor, eh?

Privateer

Captain Waddell’s orders were to head for the whaling grounds in New Zealand, then head up through the New Hebrides and the Carolines to Hawaii and eventually the Arctic. He decided this course was too risky; after three weeks in drydock, any Union ships pursuing him had to be hot on his heels. (He needn’t have worried. Thanks to sheer dumb luck, every ship looking for him was headed in the wrong direction.) Instead, he decided to set sail for Drummond Island, a popular whaling spot in the Cannibal Islands (That’s Tabiteuea in Kiribati, if we’re trying not to be colonizers.)

They ran into no one along the way. When they finally arrived at Drummond Island on March 23rd all they found were confused natives, who told them that they hadn’t seen any whalers in years. Apparently Waddell’s maps were way out of date. Whoops. The crew was dispirited but then learned from a Hawaiian tortoiseshell trader that they had passed several whalers heading towards the Carolines, to work the waters near Strong Island and Ascension Island (Kosrae and Pohnpei in Micronesia).

On April 1st, the Shenandoah sailed into Madolenihmw Bay and spotted four whalers anchored in port. They fired of a warning shot, anchored in a way that effectively blocked any escape, and sent out prize crews to capture the four vessels. Three of them were legitimate catches: the Edward Carey of San Francisco, the Hector of New Bedford, and the Pearl of New London. The fourth ship, the Harvest of Honolulu, was trickier. It was loaded to bear with muskets and ammunition, and its captain could not explain why. Waddell suspected trickery, especially since the captain and crew were all Yankees, so he declared that it was actually an American ship sailing under false colors, and seized it anyway. (It probably didn’t hurt that the Harvest was also the richest of the four prizes.)

As his men looted the four ships, Waddell went ashore to speak with the “king of Ascension Island” (probably the Nahnmwarki of Madolenhimw) and ask for permission to operate in his waters. The captain made an eloquent argument but really sealed the deal by showering the Nahnmwarki with gifts, including provisions and muskets that had been confiscated from the Harvest. The Nahnmwarki agreed to let the Shenandoah sink the four whalers and strand their crews on Pohnpei, on the condition that she split her plunder with the locals and refrain from firing her guns. Then he gave Waddell a gift in return: two chickens to be conveyed to his brother, the “big warrior” Jefferson Davis. (Ironically, this makes the Nahnmwarki of Pohnpei the only foreign head of state to officially recognize the Confederacy as legitimate.)

The Confederates took their time stripping their prizes, but they had a grand old time of it. Most importantly, the plunder included up-to-date maps of the whaling grounds. On April 4th, they burned the Pearl. On the 5th, the Hector and the Edgar Corey. And on April 10th, the Harvest.

Hmm. What else was happening on April 10th, 1865? Well, on the other side of the International Date Line it was still April 9th. As the Harvest went up in flames, General Robert E. Lee was busy surrendering his sword at Appomattox Court House. The Civil War, for all intents and purposes, was over.

Pirate

The Shenandoah had no way of knowing that, though. It sailed away from Ascension Island on April 13th, leaving behind 120 captive sailors. Waddell declined to impress any of them on the grounds that they were “Yankee scoundrels” and “Honolution mongrels.” Yikes.

The Confederates sailed around Micronesia for a few days, but there were no other whalers to be found. Consulting his new maps, Waddell decided to head north and look for plunder in the Sea of Okhotsk, between Hokkaido and Kamtchatka. For three weeks the ship headed north, through the worst weather conditions of the spring typhoon season, and eventually reached the Kuril Islands on May 20th. There they found ice fields which the extreme clipper was ill-equipped to handle. The Shenandoah changed direction again, and headed for Sakhalin Island. This was risky, because the privateer would be operating in Russian waters rather than on the high seas, but Waddell figured it would be worth the risk.

On May 28th, they finally captured another prize: the Abigail of New Bedford. The ship was technically under Russian colors, but at this point Waddell didn’t seem to care any more. Sadly, the Shenandoah had just missed the window of opportunity: Captain Ebenezer Nye had transferred some $150,000 of whale oil to a sister vessel only a few days previously. The raiding party didn’t mind all that much for a different reason: the Abigail was a booze cruise. Captain Nye had brought barrels and barrels of rum, whisky, gin, and grain alcohol to trade for Siberian furs; and some 700 bottles of brandy, wine, schnapps, and champagne for his own pleasure.

The crew celebrated by going on a massive two-day bender, during which they let another prize slip out of their grasp because they were too drunk to react quickly. Waddell was on the verge of losing the ship, and only regained control by becoming a tyrannical martinet.

The Abigail‘s mate, Thomas Manning, signed on with the Shenandoah and told him that there were at least 15 other whalers operating nearby. The Confederates couldn’t find any of them, though. (Whether that was because the other ships had moved on or because Manning was deliberately giving them bad intel is up for debate.) On June 6th they finally spotted a whole cluster of whalers near Jonas Island, but found they were separated by an impassable ice field. After weeks of fruitless searching Waddell decided he’d had enough, and plotted a course through the Strait of Amphitrite and into Arctic waters.

Back in Britain, James Dunwoody Bulloch began winding down his Confederate naval operations. On June 19th he wrote a letter to Waddell, informing that the Confederacy had fallen. He ordered the captain to cease operations and get his men to a neutral port, where they could be safely discharged and paid.

The letter would never arrive.

Back in the Bering Sea, the Shenandoah had spent most of June 21st chasing a whaler that later turned out to be a rock. That was dispiriting, but at least they found “fat-leans,” the skin and gunk leftover after flensing a whale. It was a sure sign that whalers were nearby.

Sure enough, the very next day they came across the William Thompson out of New Bedford, which was in the process of stripping a whale and could not escape in time. The crew was giddy, and why wouldn’t they be? It was their first real prize in almost a month. Unfortunately, they were about to get a harsh dose of reality. While plundering the captain’s cabin they came across a stack of old newspapers bearing the news that the Confederacy had fallen.

Waddell and his officers didn’t want to believe it. Surely this was just Northern propaganda, or a trick to get them to surrender. They went over the articles with a fine-toothed comb, looking for the tell-tale clues that would allow them to see through the lies. They focused on the tidbit that Jefferson Davis had retreated to Danville to fight on. If the “big warrior” was still fighting the good fight, so would they. Who can blame them? They had no way of knowing that Davis had been stewing in prison for weeks, that the last Confederate troops had already surrendered, and their Native American allies were about to as well.

So fight on they did. They burned the William Thompson and then went right out and caught the Euphrates, which suffered the same fate. Then they stopped another ship, the Robert Towns, by pretending to be a Russian vessel, but had to let her go because she had legitimate Australian papers. Captain Barker of the Robert Towns wasn’t fooled. He’d been in Sydney when the Shenandoah was in Melbourne, and recognized the Confederate raider at once. He sailed off to try and warn American whaling vessels nearby, but arrived to late.

The next day the Shenandoah spotted a cluster of whalers and gave chase. First they seized the Milo, out of New Bedford. Captain Jonathan C. Hawes kept trying to tell the Confederates that the war was over, but the raiders refused to believe him. As they stripped the Milo, the other whalers weighted anchor and tried to run. The Sofia Thornton gave up after the Shenandoah sent a cannonball whistling through her topsail. (No one knew it at the time, but this would wind up being the last shot fired in the American Civil War.) The Jireh Smith had almost made it to safety when the wind shifted and left it dead in the water. (The crew still had some fight in her, though: Captain Williams challenged his Confederate counterpart to single combat, though Captain Waddell prudently refused.) The Susan Abigail had a hold full of liquor and guns, and just couldn’t move fast enough to escape.

Six ships in two days! It seemed like the Shenandoah‘s luck was changing.

Waddell decided to spare the Milo, since Captain Hawes had brought his wife and daughter with him and he really didn’t feel like dealing with women and children again. He bonded the ship, transferred all of his prisoners to it, and burned the rest of the captured vessels. As soon as the Confederate raider sailed out of sight, Captain Nye of the Abigail and several others stole a whaleboat and set out to warn others. Alas, like the Robert Towns, they were too slow. Word was getting out, though, and foreign whalers began warning their American counterparts that the Shenandoah was coming.

Meanwhile, the Shenandoah pushed north through the Bering Strait. In the waning hours of June 25th, she took the General Williams out of New London. Then on the 26th she captured the Nimrod, the William C. Nye, the Catherine, the Benjamin Cummings, the General Pike, the Gypsy, and the Isabella. She only passed up one whaler, and only then because prisoners warned them that the crew was infested with smallpox. As usual, the captains bitterly complained that the war was over. Waddell and the crew refused to listen.

The Confederates took so many prisoners that they only had room for masters and mates, who were jammed into the coal hold. Regular hands were towed behind the Shenandoah in a train of whaleboats. The captured ships were burned, except for the General Pike. She was bonded and ordered to make for San Francisco. Once again Waddell used the bonding as a chance to offload his prisoners, weighing down the whaler with some 252 souls. And adequate provisions for maybe thirty of them.

The next day they captured the Waverly, trapped in a dead calm. And then, on the 28th, they hit the jackpot. Near Diomede Island they found a large group of whalers. One of the ships, the Brunswick, had struck an iceberg and was slowly sinking, and the other whalers had assembled to see what could be salvaged and auction off its cargo. They were sitting ducks for the Shenandoah. In short order they captured the Brunswick, the Congress, the Covington, the Favorite, the Hillman, the Isaac Howland, the James Maury, the Marta, the Nassau, and the Nile.

Only the Favorite gave up a fight. Captain Thomas G. Young climbed to the roof of his cabin with a small arsenal of rifles and harpoon guns, and took potshots at the Confederate boarding parties while swigging from a bottle of whiskey and drunkenly shouting “Shoot and be damned!” Waddell responded by training his guns on the Favorite. That convinced Young’s mates to try try and calm down their skipper… and while they did that, the crew stole his guns and ran for the hills. The Favorite burned like all the rest.

Well, not all the rest. Waddell spared the James Maury. Its captain, Solomon L. Gray had died suddenly in Guam, and his corpse was currently pickling in a barrel of rum below decks so his wife could take it back to America for a proper Christian burial. It would be ungallant to impose upon the Widow Gray by sinking her ship. So Waddell instead imposed upon the Widow Gray by bonding the ship and packing it to the gills with prisoners from the other vessels. The Nile got the same treatment.

This. This was what the Confederates had gone to sea for. Twenty-five prizes in just under a week! This was the sort of glory that could only be found in war. Or maybe not, since these were all defenseless civilian vessels, and the war had been over for six weeks.

Unable to push further into the Arctic ice, the Shenandoah turned back and started heading south along the Alaskan coast. They didn’t encounter any other vessels for over a month. Makes sense. They’d caught most of the American whalers operating in the area, and the few they hadn’t had been warned away by foreign vessels.

With no action to be had, Captain Waddell spent his days poring over the newspapers they’d seized during the previous week. He briefly considered trying to sail into San Francisco and taking over the city. The port was not protected by coastal batteries, and was defended only by the USS Comanche, commanded by a former shipmate of Waddell’s who he did not think highly of. In the end, Waddell realized the plan was foolish. The Shenandoah would likely be destroyed in a straight up fight with the Comanche, and even if it won there was no way for a single Confederate vessel to control a city so large without backup.

Then on August 2nd reality finally sunk in. During a friendly exchange with the British ship, the Barracouta, they got another stack of newspapers. Current newspapers. Current British newspapers. Waddell and his officers could no longer deny that the Confederacy had fallen, and that from the moment they’d left Pohnpei they had not been bold commerce raiders but deluded pirates.

Fugitive

The crew had a tough choice to make. They had no standing orders dealing with a situation like this. (Well, actually they did, but Bulloch’s letter was never going to reach them.) What was their next move? Should they head for the nearest American port and surrender there? Should they make for a neutral port, like Valparaiso? Or someplace they would find friendly faces, like Melbourne?

Captain Waddell settled the matter by announcing that the ship would make for the “nearest English port.” What his officers didn’t realize was that he meant Liverpool. Waddell’s family was there, and he wasn’t going to leave them behind.

And so began an arduous three-month journey. The Shenandoah steamed her way through the Pacific and down the coast of South America, avoiding popular sea lanes and shipping channels so she wouldn’t be spotted by Union warships and Yankee merchants. Progress was slow. Arctic ice had stripped the copper sheathing from the Shenandoah‘s keel, and the freshly-exposed teak was now riddled with barnacles and sea grass.

The stress of being hunted took its mental toll on the crew, which also began to suffer from scurvy and dehydration. Tempers flared. Master’s mate Cornelius Hunt was accused of hiding a secret stash of Yankee dollars. His sea chest was searched to no avail, and then the crew broke open the chest of sailmaker Henry Alcott just for good measure. Lieutenant Whittle and ship’s surgeon Fred McNulty were constantly at each other’s throats — Whittle called McNulty a drunk, and McNulty called Whittle a liar — and agreed to a duel. Waddell was only able to stop hostilities by first insisting any duel would have to be fought on land, and then by refusing to to stop until they reached Liverpool.

In late September, Waddell was given two petitions demanding that the Shenandoah put in for Cape Town. Neither petition was signed. The captain decided to put the proposition up to a vote, suspecting that if his officers weren’t brave enough to put their names on the petition they wouldn’t be brave enough to vote against him. He was proven correct. Liverpool it was, then.

Then, the Shenandoah lost two crewmen — the first and only casualties of the entire voyage. First seaman William Bill succumbed to tertiary siphyllis. Then George Canning, one of the men who’d signed on in Melbourne, died from complications of a pre-existing lung injury, which had either been incurred in the Crimean War or the Battle of Shiloh. (It’s hard to tell, because Canning was an inveterate liar.) They were buried at sea, with little fanfare.

On November 6th, the Shenandoah steamed into Liverpool, pretending to be a different ship out of Calcutta. When the harbor pilot came on board, the captain asked for any news about the war in America. The confused pilot responded, “It’s been over so long people have got through talking about it.”

After they were safely in port, Waddell revealed the ship’s true identity and surrendered to the British crown. The police quickly moved to arrest any British subjects on board for violations of the Foreign Enlistment Act, only to be stymied when every man jack of them, even the obvious Australians, swore that they were American. They all had to be released, and then they were paid off by Waddell.

It wasn’t much — with the cash reserves on hand, he could only afford to pay each man $1 for every $7 he was owed. This led to the final rift between Captain Waddell and First Officer Whittle. Whittle angrily claimed that Waddell had underpaid everyone and kept the remainder for himself. This sounds like sour grapes, but who knows? Waddell, for all his honor, had a very casual attitude towards the truth and there’s evidence he had been backdating his logbooks to make the Shenandoah‘s Artic killing spree seem a lot less pirate-y. It’s not inconceivable he decided to take a little something for himself now that the war was over.

Aftermath

The Shenandoah‘s crew dispersed to the four winds. Some became Confederados, lured by the promises of Emperor Maximilian to the enclave of Carlota, Mexico. Others became soldiers of fortune, fighting for the Khedive of Egypt or the President of Chile. Most returned to America after President Johnson issued a blanket amnesty for former Confederates on Christmas Day, 1868.

Captain Waddell remained in Liverpool for decades, working for a British company as skipper of a mail steamer, the City of San Francisco. Even then, he couldn’t escape his past — when he stopped at Honolulu in December 1875 he was arrested for the illegal seizure of the Harvest in Pohnpei. In December 1877 he struck a reef off of Mexico, and was fired. He returned to Annapolis and took a job with Maryland’s “Oyster navy,” protecting the Chesapeake bay’s fisheries from rogue clammers. He died in 1886.

The Shenandoah‘s Arctic rampage had lasting consequences for Anglo-American diplomacy. In 1865 the owners of the William C. Nye presented the British a bill demanding restitution of $280,212.50 for their losses. The American government and other shipping firms joined the suit, which wound up before an international tribunal in 1871. The tribunal ruled that the British bore no responsibility for the Shenandoah‘s conversion into a commerce raider, but also ruled that Governor Darling’s failure to enforce neutrality laws meant that the British were responsible for all of the ship’s actions after leaving Melbourne. In the end the British were on the hook for $15 million in damages to the American economy. Governor Darling would have probably been pilloried, if he hadn’t died in 1870.

As for the Shenandoah herself, well, the United States took possession of her but really didn’t want her. They auctioned her off to the highest bidder, the Sultan of Zanzibar, who renamed her the El Majidi and made her both the flagship of his navy and his personal pleasure craft. She capsized in 1879.

Connections

The Victorian Gold Rush is a minor event in several other stories. John Alexander Dowie (“Marching to Shibboleth”) first emigrated to Australia to work for a rich uncle who made his fortune on the gold fields of Ballarat. John Ballou Newbrough, the author of The Oahspe (“Suffer Little Children”) also worked the gold fields.

The Shenandoah’s last legitimate prizes were taken at the island of Pohnpei, within sight of the monumental ruins of Nan Madol (“Liminal Space”).

Does the name Howland sound familiar? It should. Tjhey were a prominent family of New England whalers. One of their descendants was Hetty Green, the “Witch of Wall Street.” Another was Andrew Moore Howland, the finanical backer of John Ballou Newbrough’s Shalam colony (“Suffer Little Children.”)

After the Shenandoah‘s crew dispersed many of them became mercenaries; some eventually wound up going to Chile with artist James McNeill Whistler. (“Crepuscule in Blood and Guts”).

The Sultans of Zanzibar had terrible luck throwing together a decent navy. After the sinking of the El Majidi, the HHS Glasgow became their navy’s flagship until it too was sunk during the Anglo-Zanbibar war of 1896 – a conflict most notable for only lasting 44 minutes ( “Microaggression.”)

Sources

- Baldwin, John and Powers, Ron. Last Flag Down: The Epic Journey of the Last Confederate Warship. New York: Crown Publishers, 2007.

- Bonner, Robert E. “The Salt Water Civil War: Thalassological Approaches, Open-Centered Opportunities.” Journal of the Civil War Era, Volume 6, Number 2 (June 2016).

- Chaffin, Tom. Sea of Gray: The Around-the-World Odyssey of the Confederate Raider Shenandoah. New York: Hill and Wang, 2006.

- Hanlon, David L. Upon a Stone Altar: A History of the Island of Pohnpei to 1890. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1988.

- Hearn, Chester G. Gray Raiders of the Sea: How Eight Confederate Warships Destroyed the Union’s High Seas Commerce. Camden, ME: International Marine Publishing, 1992.

- Jones, Virgil Carrington. The Civil War at Sea, Volume 3: The Final Effort. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1962.

- Peifer, Douglas C. “Maritime Commerce Warfare: The Coercive Response of the Weak?” Naval War College Review, Volume 66, Number 2 (Spring 2013).

- Schooler, Lynn. The Last Shot: The Incredible Story of the CSS Shenandoah and the True Conclusion of the American Civil War. New York: Ecco, 2005.

- Smyth, Terry. Australian Confederates: How 42 Australians Joined the Rebel Cause and Fired the Last Shot in the American Civil War. North Sydney, NSW: Ebury Australia, 2015.

- Thorp, Daniel B. “New Zealand and the American Civil War.” Pacific Historical Review, Volume 80, Number 1 (February 2011).

- “Another privateer at work.” New York Daily Herald, 2 Jan 1865.

- “Alleged breach of the foreign enlistment act.” Liverpool Mercury, 5 Jan 1865.

- “The prosecution of the commander of the Shenandoah.” Manchester Guardian, 6 Jan 1865.

- “The Shenandoah.” Melbourne Age, 26 Jan 1865.

- “Breach of the Foreign Enlistment Act.” Sydney Morning Herald, 28 Mar 1865.

- “Australia.” London Times, 13 Apr 1865.

- “The pirate Shenandoah.” New York Times, 27 Aug 1865.

- “The ‘Shenandoah.'” Aberdeen Jounral, 8 Nov 1865.

- “The pirate ‘Shenandoah.'” Philadelphia Inquirer, 23 Nov 1865.

- “Shenandoah sent to New York; her captain and crew set free.” Sydney Morning Herald, 9 Jan 1866.

- Ottawa Citizen, 20 Sep 1867.

- “Rescue of a Zanzibar war steamer.” Gurnsey Star, 2 Jan 1873.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: