We Live Inside

greetings from the inside of the Hollow Earth

Incarnation (1839-1868)

Cyrus Reed Teed, was born on October 18, 1839 in Trout Creek, New York. The Teed family was well-off — so well-off that the part of town where they lived was called “Teedville” — but Cyrus’s immediate family was not. His parents, Jesse Teed and Sarah Tuttle, had eight children to support and were barely getting by.

In the early 1840s the Teed family relocated to Utica to live with Sarah’s father, a Baptist preacher, who took over young Cyrus’s education. The goal was to train Cyrus for the ministry, but unfortunately the family’s financial needs were more pressing. In 1850 11-year-old Cyrus dropped out of school to become a “hoggee,” or towpath driver, on the Erie Canal.

It was a boring job driving oxen along a straight road for eight months of the year, but it had one upside. It gave young Cyrus time to indulge his favorite hobby, reading, and he read every book he could find, on topics as diverse as philosophy, history, and science. Freed from the influence of his grandfather, Cyrus developed a stubborn independent streak.

At the age of 20, Teed married Fidelia Rowe, a distant cousin, who was soon pregnant with their only child, Douglas Arthur Teed. Then he shocked his family by turning his back on the church and apprenticing with his uncle, Dr. Samuel Teed, a practitioner of eclectic medicine.

Eclectic medicine was a populist reaction to the increasing professionalization and scientification of the medical field. It was an loose alliance of doctors who couldn’t understand the new medicine and felt left behind; doctors who were opposed to treatments like bleeding, purging and pharmaceuticals on moral and intellectual grounds; and quacks. In practice, it was a strange hodgepodge of what we’d call “alternative medicine” today — mostly ineffective methods of treatment like folk medicine, herbalism, homeopathy, and osteopathy. Some practitioners even dabbled in fields like alchemy, mesmerism, faith healing and other outright quackery.

In 1862 Teed briefly put his studies on hold to enlist in the Union Army. His service was short. In August 1863 he collapsed from sunstroke while on maneuvers and developed a psychosomatic paralysis in his left leg. He spent two months in a field hospital and was eventually declared unfit for duty and discharged.

Teed finished his studies in 1868, receiving a doctorate from the the Eclectic Medical College of the City of New York. Dr. Teed moved back to central New York to open a practice in Deerfield. He went all-in on advertising, painting the outside of his office with the giant letters declaring, “He who deals out poison deals out death” — a not-so-subtle dig at the pharmacists just down the street.

Dr. Teed’s specialty was electro-alchemy or alchemo-vietism, the treatment of ailments through the application of powerful electric shocks and magnetic fields designed to rebalance the body’s humors. It was a strange fusion of cutting-edge science with ancient metaphysical ideas, and perfect for Cyrus, who was also a strange combination of the world that had been and the world that was to come. He would treat patients at his clinic all day, and spend the evenings tinkering with electrical equipment in his lab trying to unlock the secrets of the universe.

He hadn’t left his old life behind, though. In 1869, Teed was formally baptized by his grandfather. When the Holy Spirit descended on him, he thought he heard a voice faintly calling to him. But surely, he must have been mistaken.

The Illumination of Koresh (1869)

In October 1869, Teed was working in his lab when he discovered the philosopher’s stone. You heard me right: he discovered the way to convert base matter into purest gold. That would probably be enough for most of us, but not for Dr. Cyrus Reed Teed. He had to go further and conquer death itself.

Here’s what happened next, in Teed’s own unique, florid, impenetrable gibberish:

I experienced a relaxation at the occiput or back part of the brain, and a peculiar buzzing tension at the forehead or sinciput; succeeding this was a sensation as of a Faradic battery of the softest tension, about the organs of the brain called the lyra, crura pinealis, and conarium. There gradually spread from the center of my brain to the rest of my body, and apparently to me, into the auric sphere of my being, miles outside of my body, a vibration so gentle, soft and dulciferous that I was impressed to lay myself upon the bosom of this gently oscillating ocean of magnetic and spiritual ecstasy. I realized myself gently yielding to the impulse of reclining upon the vibratory seas of this, my newly-found delight. My every thought but one had departed from the contemplation of earthly and material things. I had but a lingering, vague remembrance of natural consciousness and desire.

Teed found himself floating in a void, unable to move or speak. He started to panic, thinking that his experiments had somehow severed his soul from his body, but he was calmed when he heard the sweetest, most feminine voice speaking to him. He was shocked to realize the voice was his own, and also, the voice of God.

Soon, he was face to face with God herself: a gloriously regal, unutterably beautiful, majestic vision of womanhood. She revealed his true nature: Cyrus Reed Teed was the divine “Horos,” son of Osiris and Isis, the masculine aspect of the godhead incarnate. He had been sent from the heavens time and time again to redeem the world, and each time he had strayed from his mission and been laid low by his enemies.

This time it would be different. Teed’s experiments had interrupted the eternal cycle, giving him a rare glimpse of the spiritual world and the ability to transcend his fate. In this life, he would be reunited with the feminine aspect of the godhead, and together they would save the world. God bade him farewell, and he found himself back on the earthly plane, lying on the cold floor of his laboratory.

Teed came to the reasonable conclusion that he had knocked himself out with an electrical shock and had a strange dream. He climbed into bed next to his wife to sleep it off. But three times that night he was roused from his slumber by the sound of a great chariot flying above his house. As he stared at the ceiling he could feel himself slowly attuning to the vibration of the entire universe and becoming one with the cosmos.

He knew then it was all true: he was the Messiah.

In secret, he began organizing the principles of his new religion. No, more than a religion: the ultimate fusion of religion and science. Like eclectic medicine, Teed’s religio-science was a strange hodgepodge of primitive Christianity, Swedenborgian mysticism, Spiritualism, and alchemy, with a healthy dose of millennialist paranoia thrown in for good measure. Teed rechristened himself “Koresh” (the Hebrew version of Cyrus) and called his new creed “Koreshanity.”

Here’s what he believed.

- God was a perfect biune being with male and female aspects.

- Cyrus Reed Teed was the male aspect of the godhead incarnate, and the Messiah. He had been reincarnated several times, as Adam, Enoch, Noah, Moses, Elijah, and Jesus. This seventh incarnation was to be his last.

- Men and women, each representing a portion of the godhead, were equitable (but not equal). Sex and marriage made women the slaves of men, which destroyed any equity between them. Consequently, everyone should be celibate and unmarried. Sexual urges should instead be sublimated into the worship of God, i.e., Dr. Cyrus Reed Teed.

- The end times were soon to be upon us. Once those refocused sexual energies had charged Teed’s “anthropostic battery” his consciousness would expand in “theocrasis” and he would unite with the feminine godhead, recreating the perfect biune form of God here on Earth. The new God would destroy our corrupt capitalist society, transform everyone into perfect hermaphrodites, banish death, and usher in a new golden age.

- This could be accomplished because matter and energy were one and the same, and one could be destroyed to create the other. By “energy” he meant not only electricity and magnetism, but also spiritual energy.

- The Bible was a true expression of the divine mind, but was written in a symbolic, coded way that had to be interpreted by a prophet for mass consumption.

- Heaven and Hell were not literal places, but spiritual conditions that existed solely within the mind. After death, souls were not rewarded or punished for eternity, but reincarnated in new physical shells. The cycle could only be broken by conquering death itself and achieving physical immortality.

- In the meantime, people should live like the primitive Christians: all property should be shared communally, and men and women should live apart.

Now, most of these ideas were all fairly common in mid-Nineteenth Century American religions. There as no shortage of cults proclaiming a new Messiah, prophesying the end of the world, and calling for communal living, celibacy, and the equality of sexes. (It was at least novel for one creed to profess all of these tenets simultaneously.) But Teed had one more belief that set him apart from the crowd:

- The Earth is a hollow sphere.

Even that wasn’t an entirely uncommon belief in the Nineteenth Century. Many intelligent people believed that there were giant openings at the North and South Poles through which the hidden lands of the inner Earth could be accessed. (There’s an excellent episode of The Constant that talks about this, and I’ll share the link on our web site.) But Teed added his own twist that made it truly unique.

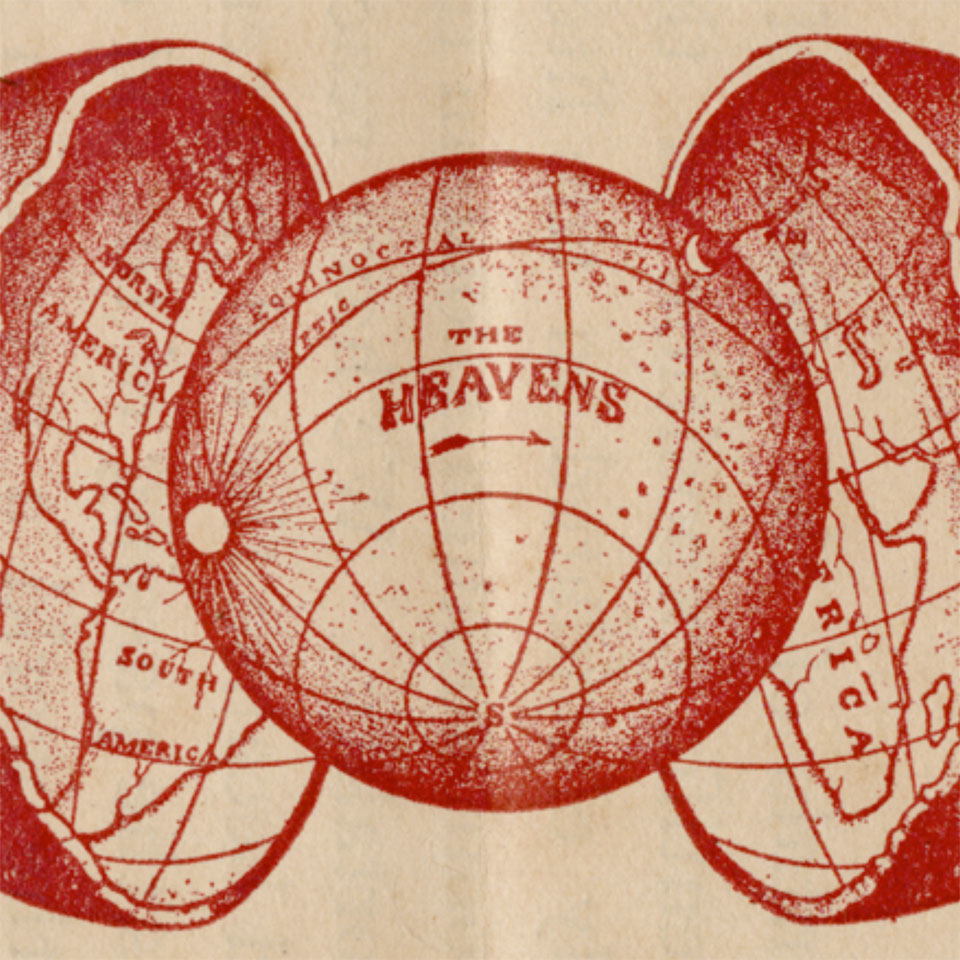

- The Earth is a hollow sphere… and we live on its inner surface.

In Teed’s cosmology, the “cellular cosmogony,” the entirety of the universe is a hollow sphere with a 17-layer crust 100 miles thick. The outermost layer consists of a thin shell of pure gold, and the innermost layer is the world around us. In the center of this system is an invisible electro-magnetic battery that powers everything. The sun, moon, and stars are all illusions, created by mercurial mirrors reflecting the light of the “invisible” battery onto the “aboron atmosphere” of the heavens. The sphere is all that is, and outside of it there is nothing.

The cellular cosmogony was born from the same existential dread of an infinite universe that inspired horror writers like H.P. Lovecraft. Unlike Lovecraft, Teed could not succumb to this dread. To him, the whole purpose of science and philosophy was to study the universe in order to know God through their works. If the universe was infinite, it was impossible to know God because you could never know all of their works. So Teed denied the infinite universe and created a comforting, self-contained one to take its place, declaring:

To know of earth’s concavity is to know God, while to believe in the earth’s convexity is to deny Him and all His works.

So, to summarize, a thirty-year-old quack in upstate New York accidentally knocked himself out with an electric shock. When he recovered he declared that he was the Messiah, God was a hermaphrodite, the world was coming to an end, and you should stop having sex and give away all your money and property. And oh yeah, and we lived on the inside of a hollow earth.

Folks, it only gets weirder from here.

Central and Circumferential Limitations (1870-1885)

Needless to say, Cyrus Reed Teed could not keep the good news to himself. He started preaching his new creed to anyone who would listen, and quite a few who wouldn’t.

Teed was a commanding, charismatic orator but he could not convince the good people of Deerfield and Utica that he was the Messiah. Let’s face it, it was a tall order. They’d known him since he was knee-high to a grasshopper. If the neighbor’s kid came to you and told you he was really the son of God, would you believe him? Teed was dismissed him as a crank, a narcissist with a god complex, or a simple lunatic like his brother Wilson (who talked to “spirits” in electrical wires).

It didn’t help that Teed decided to step up his critique of mainstream Christian denominations, which he considered the degraded tools of our capitalist oppressors.

Christianity so called… is but the dead carcass of a once vital and active structure. It will rest supine until the birds of prey, the vultures and cormorants of what is falsely called liberalism have picked its bones of its fleshly covering leaving them to dry to bleach and decompose.

Teed’s aggressive proselytizing quickly turned him into a social pariah. The Baptists kicked him out of the congregation and his patients started seeing other doctors. On the brink of financial ruin, he moved his family to Binghamton to make a fresh start. (It also allowed him to leech off of his in-laws, who lived nearby.)

In Binghamton, he made a new friend: Dr. Abiel W.K. Andrews, or “Abie.” Abie was a local doctor — a real one — and a fellow war veteran. He found Teed intelligent, quick-witted, and fascinating. They spent many an evening having lively and earnest arguments about philosophy and religion. In the course of these arguments Abie slowly became a convert to Koreshanity. He would be Teed’s closest friend and confidant.

But Andrews was the only convert he’d make in Binghamton. Southern New York had seen so many revivals that it was sick of new religions. Before long, they’d had enough of the new Messiah and quietly suggested he should leave town.

This was the new pattern of Teed’s life. He would move to a new town, hang out his shingle, and get to know the community. Then he’d get overconfident and start preaching to the locals. Eventually he’d have to flee town before he could be run out of it on a rail. Then it was on to the next town. He spent the better part of two decades criss-crossing New York and parts of Pennsylvania in this manner.

When he was in-between jobs Teed would stay with the Andrews family, where he and Abie worked on strategies to create converts. They tried to identify groups that might be receptive to the Koreshan message so Teed could infiltrate them and spread the good word. They tried the Young Men’s Christian Association, the Methodists, and countless others, to no avail.

Since the Koreshan creed called for communal living, Teed and Andrews made a study of successful religious communes in preparation of opening one of their own. They found much to admire and copy as they read about the Oneida Community, the Shakers, the Harmony Society, the “brownstone utopia” of Stephen Pearl Andrews, and Thomas Lake Harris’s Brotherhood of the New Life. Teed even visited the Shaker enclave in Mt. Lebanon and briefly became an initiate, though he never quite became a full member.

His visit to the Harmony Society in Economy was less fruitful. Encouraged by their polite responses to his letters, he was convinced that he would take over the entire community with his fiery sermons and magnetic personality. Instead, the Society’s trustees smiled politely and sent him on his way with a check for $100. Teed saw that as a personal insult and declared:

When I am ready to use the people of Economy for the Divine use, I shall simply command, not beg.

That was a pretty bold claim for someone who could count his followers on one hand and have enough fingers left over to poke you in both eyes. It was even worse than that makes it sound. Other than Abie, the only other converts to Koreshanity were Teed’s younger siblings Emma and Oliver. He couldn’t even convert his own wife and son.

Fidelia Teed was not a fan of their family’s new itinerant lifestyle. When she was diagnosed with tuberculosis in the mid-1870s, she used that as an excuse to take young Douglas and move in permanently with her sister in Binghamton. Koreshan biographers would have you believe that the separation was an amicable one, and that Delia supported her husband’s holy work. The course of their lives would seem to indicate otherwise. Cyrus rarely visited his family, barely bothered to write, and when Delia finally succumbed to her condition Douglas was taken in, not by his father or relatives, but by a wealthy local widow.

In 1877, Teed made his first real attempt to start a commune at his parents’ house in Moravia. It was a pretty sad commune since it consisted entirely of his own immediate family, who were already pooling their incomes. Eventually Jesse Teed decided he’d had enough of his son’s tomfoolery and put an end to the whole thing.

The next year the Teed family started a business making mops. Cyrus, who was between jobs, was brought in to help manage the factory. He soon realized that mop-making could be the economic backbone of a commune, the way that furniture-making had been for the Shakers. He re-established the commune and even managed to make three new converts, all married women who left their husbands to follow the new Messiah.

Married woman found Koreshanity strangely appealing. They didn’t seem to care too much about anthropostic batteries or cellular cosmogonies. But the parts about equal rights, not having to have sex with their doltish husbands, and not being trapped in a loveless marriage? They ate that up with a spoon. It didn’t hurt that Cyrus Teed was a charming, handsome doctor with penetrating eyes and a sensual voice. Or that he actually talked to them and took a personal interest in their problems. It was like having a gay best friend who was also sexy Jesus.

The good people of Moravia were not happy to learn that Teed was sharing a roof with three women he was not related to. False rumors that the Koreshans practiced bigamy and free love started to circulate. Fortunately, before a lynch mob could form, the mop business failed, the commune collapsed, and Teed left town.

This time Teed wound up in Syracuse, where he opened the Institute for Progressive Medicine, specializing in electrotherapy for neurasthenia and hysteria. As those afflictions occurred almost exclusively in married, middle-class women he was guaranteed a steady stream of patients and potential converts.

Alas, one of those patients proved to be his undoing. He had been treating a Mrs. Cobb for nervous prostration and managed to convince her to make a small donation to support his new commune — $20 from her pocketbook, a small ring, and $5 she pinched from her son’s piggy bank. Once she was separated from the fast-talking doctor she realized she’d made a horrible mistake. She went to the police and swore out a complaint against Teed for obtaining the money under false pretenses.

Teed’s defense was there were no false pretenses. He was the Second Coming of Christ, in 1885 he would transcend the mortal plane and return fifty days later to usher in the new millennium, and his followers would live forever.

As you might expect, that defense did not fly with the good people of Syracuse, and Teed was savagely mocked by the press. And that was just for the Messiah stuff — if they knew about the hermaphrodite God, the sex batteries and the hollow earth it would have been much, much worse. It was Koreshanity’s first real widespread publicity, and it was uniformly negative.

With his name and reputation in tatters, criminal charges pending, and the threat of vigilante justice starting to rear its ugly head, Teed decided to cut his losses. He returned Mrs.’s Cobb’s money and skipped town.

The Nucleus of the Bridal Church (1884-1885)

A disappointing result, but Teed was finally starting to figure it out. He decided to set up a base of operations somewhere bigger: New York City. Teed rented a small third-floor apartment on 135th Street, and set up a small commune with four women who followed him from Syracuse.

It fell apart almost immediately. Eclectic medicine had fallen out of favor in the city, and Teed was struggling to find patients. His four followers were no help, contributing very little to the commune’s financial needs. When they fell behind on rent the women moved back upstate. Teed took smaller lodgings and tried to start over from scratch.

He somehow managed to finagle an introduction to a group of intellectuals in Brooklyn led by a prominent Spiritualist named Mrs. Peake. He dazzled the group with his scientific knowledge of the human brain and his alchemo-vietic theories about its ability to channel psychic energy. Mrs. Peake was delighted. The spirits told her that with Teed’s help her group would form the “nucleus of the Bridal Church” and usher in a new age of communism. The spirits were right about that, but wrong about her involvement. Within a few weeks Teed had taken over leadership of the group.

This new platform allowed Teed to expand his range, and soon he had a weekly lecture at the Faith Healing Institute on 59th Street and was writing articles for its journal. Teed’s strange brand of religio-science and feminism caught the attention of prominent suffragette Cynthia Leonard, who invited him to speak at her Science of Life Club. Teed was once again a splash, and he was invited to join.

That did not sit well with the club’s previous golden boy, Stephen Pearl Andrews, the same Stephen Pearl Andrews whose “brownstone utopia” Teed had admired from afar. Andrews thought Teed was trying to force him out and take over the club, the same way he had taken over Peake’s group. He was right, but Teed never got the chance.

Teed’s activities with the Science of Life Club caught the attention of Elizabeth Rowell Thompson, a free-thinking society matron who collected scientists and philosophers the way some people collect art. She’d find some promising young thinker and offer them lodgings, a monthly stipend and tailored suits in exchange for publication rights to their works. She made that offer to Teed, and he jumped on it.

At first it was a productive partnership. Thompson introduced Teed to her society friends in Washington, DC and Stamford, Connecticut. But Teed found himself creatively blocked, and after nine months he had nothing. So Thompson tried to get him to assist one of her other authors, who was writing a book about free love and non-vaginal intercourse. The thought of either revolted Teed, who soon he found himself completely boxed out of Thompson’s circle and without funds. He had to swallow his pride and write to his friend Abie, begging for enough money to buy a train ticket out of town.

The Central Stellar Vortex (1886-1893)

Just as things started to fall apart, Teed received a letter from a Mrs. Thankful H. Hale. Mrs. Hale had heard him speak in New York and was impressed. She invited him to come speak at the September 1886 convention of the National Association of Mental Science in Chicago, all expenses paid. Teed could hardly say no to a chance to speak to a room full of potential converts, and the phrase “all expenses paid” sounded pretty good to him too.

Mental science was a strange adjunct to eclectic medicine, an attempt to add scientific legitimacy to some magical thinking that had been bubbling just under the surface of American thought for years: that the root cause of all your infirmities, whether physical, mental, social or spiritual, is your own thoughts. The secular-ish manifestations of this concept include Creative Visualization, The Secret, and The Power of Positive Thinking. Its more overtly religious manifestations include faith healing and Christian Science.

In fact, in 1886 that was hot-button issue of mental science — whether to stay the course and seek scientific legitimacy, or to fully embrace the straight-up spiritualism of Mary Baker Eddy. It was one of the issues to be settled at the convention. Other highlights included demonstrations of mind-cures and faith healing and lectures about the science of the brain.

Teed first addressed the convention on Friday. It must have been a hell of a speech, because later that day he was elected president of the Association, defeating Professor Andrew J. Swarts in a shocking upset. Not only had Swarts organized the convention he was also the editor of Mental Science Magazine, president of the Mental Science University, and founder of the Mental Science Church. Despite all that clout he could not withstand the fiery force of the new Messiah’s personality, and his ability to make fast friends. (Teed, of course, did not mention that he was the Messiah to the Association. After seventeen years he’d finally learned that it probably wasn’t the start for a sales pitch.)

On Sunday, Teed closed out the convention with a barn-burner of a lecture on the brain. He called the Bible the foundation of all science. He declared that all disease was caused by mistakes in thought, and backed it up with his scientific knowledge and bits of esoteric mysticism. He proclaimed that by understanding the brain and marrying science with faith you could heal the body and eradicate death. As his finisher, he performed a faith healing on an obese woman who could barely walk. It brought the crowd to its feet. Teed’s domination of the Association was complete.

(Teed took note of his success, and this would be his new modus operandi: find a larger, more powerful organization and take it over from within. It rarely paid off, but when it worked it paid off big.)

Over the next few months Teed relocated his operations to Chicago and began transforming the National Association of Mental Science. First, he reorganized Mental Science University into the “World’s College of Life,” opening it up to women, offering courses in eclectic medicine, and awarding its graduates doctorates of “psychic and pneumic therapeutics.” He set up a publishing house to print his pamphlets and a monthly newsletter the Guiding Star (later the much catchier Flaming Sword.) He also started his first real church, the Assembly of the Covenant, and a gateway organization for the curious, the Society Arch-Triumphant. Together these organizations formed the nucleus of his new religion, the Koreshan Unity.

Things were finally starting to come together. He attracted new converts, as usual many of them educated middle-class women sick of the monotony of marriage. (One wag who attended a meeting wryly noted that, “The women disciples were all Marthas. There might have been one Mary.”) Teed also softened a bit, making one small change to his dogma. He conceded that his date for the second Second Coming was somewhat premature, and pushed it back five years to 1891. And later to 1893. And then to whenever.

The Koreshans opened a full-fledged commune in Chicago, in a three-story building near College Place. It was unfurnished, and thanks to some cash-flow problems, its residents could rarely afford luxuries like “heating” and “food.” They also opened a co-op, the Koreshan Bureau of Equitable Commerce, to begin the transition of our corrupt capitalistic society to a moneyless system based on social credits.

He still managed to find trouble, though. In February one of his students, Mrs. Renew Benedict, sought Teed’s medical expertise for her bedridden husband Fletcher. Teed declared that Fletcher would be fine, gave him a quick laying on of hands, and prescribed a hot bath and a short treatment of lobelia and gelsemine, both of which are mildly poisonous. But Fletcher would not be fine. Fletcher had pneumonia and died. Chicago authorities convicted Teed of practicing medicine without a license, and fined him $300. Teed paid the fine and thanked his lucky stars that they hadn’t charged him with murder.

In October 1888 the Koreshan Unity held a grand convention in Chicago’s Central Music Hall, which pulled in 40 converts all in one go. It was a grand triumph for the Koreshans, but the expense was incredible. In fact, Teed had spent most of the previous two years teetering on the edge of bankruptcy because he spent all his money on printing pamphlets and pushing promotional efforts, like a religious version of a dot-com company. The only thing that saved him from ruin were the near-bottomless pockets of his wealthiest followers, like Wisconsin grocer Henry D. Silverfriend and Berthaldine Boomer, wife of a railroad tycoon.

It was pretty clear that Teed was terrible with money. (It’s almost as if he forgotten that he’d discovered the way to turn base matter into gold.)

That was about to change thanks to Mrs. Annie Ordoway. Ordoway was one of the first students of the World College of Life, and later its head. She was, in many ways, his exact opposite. Teed was gentle, feminine man. Ordoway was a brusque, masculine woman. Teed was a fanciful dreamer. Ordoway was tough and practical. Teed was charismatic. Ordoway was… not.

Soon, Teed had decided that Ordoway was the feminine counterpart whose coming had been foretold. He rechristened her “Victoria Gratia” and promoted her to “Dual Associate, Pre-Eminent” of the Society Arch-Triumphant. To his inner circle he announced that at the right time he would undergo “theocrasis,” and his spirit would enter Victoria’s body and the united being would become the universal mother-father. In the meantime, Victoria would be in charge of the tedious day-to-day operations of the church while Teed took care of the visionary big picture stuff.

Victoria Gratia was not popular with the rank and file Koreshans of the Unity. They debated whether she was actually divine, was to become divine after theocrasis, or was just an empty vessel for his divinity. They challenged her decisions and confronted her and argued with her every decision.

Many histories attribute this resistance to a sort of natural cattiness or status-seeking inherent to large groups of women, which is sexist and reductive. Honestly, it’s just the negative dynamic you see in any large dysfunctional organization: you hate the terrible middle managers you deal with on a daily basis but not the terrible folks in upper management who you rarely interact with.

We should also consider the possibility that it was entirely intentional. By choosing an uncharismatic successor, Teed removed any possibility that his authority might be usurped.

In any case, Teed made his choice and stood by Victoria, even when it meant expelling followers like Thankful Hale, who had invited Teed to Chicago, or Lizzie Robinson, who had put a roof over his head when he first arrived.

Some of the blame also has to lie with Teed’s recruiting tactics. His approaches were oddly seductive, and more than one convert misunderstood Teed’s overtures to be sexual. He’d spend months wearing down the resistance of converts, promising them positions of power in the organization and freedom of the tyranny of marriage, and then dump them into a situation where instead they had to deal with the tyranny of Victoria Gratia.

Converts weren’t the only ones who took Teed’s overtures to be sexual. Angry ex-husbands swore out a constant litany of criminal complaints against him, sued him for alienation of affection, and even threatened commune residents with revolvers.

Teed had momentum, though, and could not be stopped. He sent missionaries across the country and made converts in Baltimore, Detroit, Denver, Washington, DC, and more. In Pittsburgh he debated Charles Taze Russell, head of the Watchtower Society, to great acclaim. He had his greatest success in in San Francisco, he established another commune in the Castro called Ecclesia, which was to be the “Golden Gate Hippocampus” of the Koreshan Unity. The San Francisco press had great fun with Dr. Teed, casting him as a Svengali-esque “lady-lurer,” but only raised local interest in Koreshan teachings further.

Ecclesia would also turn out to be Teed’s biggest headache. When the director of the commune, “Professor” Royal O. Spear, returned to Chicago in October 1891 his wife promptly informed him that Teed had made a pass at her, claiming that it wouldn’t be adultery because he was divine and could do no wrong. It was almost certainly a lie, but it worked. Spear and Teed had a huge falling-out, Spear quit the Koreshan Unity, and gave a series of largely incoherent lectures denouncing the Koreshans and revealing their secrets.

Spear’s biggest revelation was that Teed had been working for years to create a “union of celibate societies” pulling together the Koreshan Unity, the Shakers, the Harmony Society, the Brotherhood of the New Life, and more. None of these groups were theologically compatible, but Teed foolishly thought he could reconcile their financial interests and paper over any cracks with is personal magnetism.

He made the greatest inroads with Pittsburgh’s Harmony Society, whom he had visited years earlier. At this point the Society had dwindled to a mere handful of members, and Teed’s plan was to have a few key men join the organization and form a voting block that could install him as the new Trustee and give them access to the Society’s vast fortune. One of those men was purportedly John S. Duss, the current Junior Trustee of the Society. The resulting scandal scuttled the union of celibate societies and rattled the Koreshans and Harmonists.

There was probably never much of a plot to begin with. Teed had been sending people to work with the Society and learn their methods, but none were ever made full-fledged members, indeed, few people ever were. Duss had been sending money to Teed, but it was the same sort of mild financial support the Society gave to many other charitable organizations.

The most likely scenario was that Duss had been using the threat of a Teed takeover to create an external threat to distract his foes inside the Society. (Though I should note that in his biography, Duss declared Teed’s vision of a hollow Earth to be 100% scientifically accurate.) Teed was happy to play along because it made him look wealthy and powerful, and therefore more attractive to potential converts.

Spear also revealed one other thing: that noted Spiritualist medium, stockbroker, and then-presidential candidate Victoria Claflin Woodhull was employing a Koreshan as her personal secretary. Woodhull was one of the most controversial figures of the day, and believed in universal suffrage, Marxism, free love, and legalized prostitution. But Koreshanity was a step too far even for her. The secretary was fired, and she publicly denounced Teed.

As part of the fallout from the Spear scandal, Teed decided to close Ecclesia and relocate all of its sixty residents to Chicago. The College Place commune had been barely adequate for its thirty residents couldn’t handle more. The Koreshan Unity wound up renting a mansion in Washington Heights that Teed re-christened “Beth-Ophrah.” His inner circle moved into the mansion’s relative luxury while the other communards were moved into a dilapidated tenement seven miles away in Normal Park.

At this point the Chicago Evening Journal started to stir the Unity’s new neighbors into a NIMBYish frenzy. They established a “vigilance committee” to keep the Koreshans out of their neighborhood. Rocks were thrown at the house, and bombs were even left outside on the sidewalk. When Teed was arrested for alienating the affection of one Mrs. Thomas Cole, the vigilantes held a rally in Normal Park calling for him to be tarred, feathered and run out of town on a rail. When the Cole case went to trial, they tried to knock Teed down the courthouse steps kill him.

(The Cole case was eventually thrown out of court by a judge who tired of Cole’s constant attempts to postpone it. Thomas Cole finally got his day in court in 1897, but what he thought would be damning testimony about Teed actually portrayed Cole as a terrible husband and the case was thrown out, this time with prejudice. Annie Cole remained a Koreshan for years. She eventually married Oliver Teed, the Messiah’s brother, and both of them were kicked out of the Unity.)

With Chicago increasingly turning on the Koreshans, Teed declared that the end was nigh. The war for our souls would be fought at the new Babylon, the 1893 World’s Fair and Columbian Exposition. Teed would die a martyr’s death, ascend to heaven, then theocratize and return as God incarnate. A Chicago Tribune reporter mockingly asked supporters:

Do you mean to say that you believe that Dr. Cyrus R. Teed will go shooting off into heaven like a skyrocket, perhaps from this very porch at Nos. 2 and 4 College Place, Chicago?

The Immortal Man was not martyred in 1893, but the relationship between the Koreshan Unity and the local community continued to deteriorate. Teed decided that maybe it was better for the Koreshans to get out of town.

The Vitellus of the Cosmic Egg (1893-1905)

In October 1893 Teed and three of his closest advisors, including Victoria Gratia and financial backer Berthaldine Boomer, took a trip to Florida to see if they could purchase a hotel in Punta Rassa, just south of Fort Myers, be the site of their next commune. The price was more than the Unity could afford, though Teed strung the owners along so they didn’t realize how limited his funds were. In the meantime, he used it as a chance to lecture and distribute literature.

A local farmer, Gustave Damkohler, heard about some Northerners looking to purchase land and thought his swamp-front property in nearby Estero might do. The Koreshans went out to meet him, and what happened next is a matter of some controversy: either Damkohler had a genuine religious conversion upon meeting the great Koresh, or Teed and his bevy of sirens befuddled Damkohler’s mind with some chaste pampering. Whatever the cause, the farmer signed over some 300 acres to the Koreshan Unity for the cut-rate price of $200. The Koreshans also promised to “take care” of Damkohler in his dotage.

Teed was pleased by his new land in Estero. He declared it to be the “vitellus of the cosmic egg” and the site of the “New Jerusalem.” He envisioned a mighty megalopolis, a city of ten million people with wide avenues, huge parks, and fantastic infrastructure right out of a Jules Verne novel. He sent back to Chicago and soon a small army of Koreshans were clearing the land and building permanent structures.

It was not easy work. The Koreshans were hopeless city slickers with no idea what they were doing, and at first most of the hard work had to be done by Gustave and his son Elwin. But they learned quickly, and over the next few years the property was transformed from swampland to a rustic but comfortable garden community with a general store, post office, an outdoor theater and a small gallery. For the Koreshans the humid swampland was a cozy place to unwind, an idyllic break from the heated battles they were constantly fighting in Chicago.

They still made plenty of mistakes. At first they nearly starved because planting was managed by a former Greek and Latin professor, who decided to experiment with growing Biblically-inspired crops that did not prosper in Florida’s subtropical climate. The Damkohlers convinced them to switch over to citrus crops at just the right time. In the winter of 1894-5 an unseasonable cold snap devastated Florida — but everything south of Fort Myers was spared. With oranges in high demand the Koreshans started pulling in real money. Which Teed started spending as soon as it came in, as usual.

In its early years, Estero was teetering on the verge of bankruptcy. Most of Teed’s followers thought he was just optimistic or naive when it came to money, but others like Henry Silverfriend thought he used financial distress as a way of motivating everyone to work harder. Victoria Gratia always had her hands full managing the Unity’s debts and shuffling around their property so it couldn’t be attached by creditors.

With their financial situation finally stabilized, the Koreshan Unity embarked on its next venture: scientifically proving once and for all that we lived on the inside of a hollow earth. Leading up the effort was “Professor” Ulysses Grant Morrow, a stenographer and gentleman scientist from Pittsburgh. Morrow had originally been a flat-earther but changed his views after hearing Teed debate Charles Taze Russell. He was appointed the cult’s chief astronomer and geodesist.

As a former flat-earther, Morrow was intimately familiar with experiments that could be used to prove the Earth was round. He also knew, thanks to a quirk of topography, that those experiments were useless because they would produce the same results whether you were on the inside or outside of a sphere. No, there was only one way to do it: to create a truly straight line, parallel to the Earth’s surface when you started, and extend it infinitely. If we were on the outside, the line would rise into the sky. If we were on the inside, it would eventually touch the ground.

To conduct the experiment Morrow created a 12′ long t-square which he called the “Rectilineator,” and developed techniques to ensure that it would stay perfectly level. (Essentially, he built multiple Rectilineators and just kept moving them in a line, end over end, and developed techniques to stabilize them while he built supports.)

The Koreshans gave the Rectilineator a dry run on the shores of Lake Michigan in the summer of 1896, and took it down to Florida for the final experiment in early 1897. Over several grueling months a work team meticulously moved the Rectilineator several miles over the swamp and beach. When they reached the coast, they extended the line for another few miles with boats and poles, taking sightings through a telescope.

Morrow checked and double checked his calculations, and determined the line projected by the Rectilineator would enter the Gulf of Mexico about about four miles from its starting point, meaning the Earth’s surface curved upwards. He declared the experiment a success, and Teed included Morrow’s experiment design and dataset in his book The Cellular Cosmogony, which detailed the mechanics of the Koreshan cosmology.

Now, you and I know that we don’t live on the inside of the Earth, but Morrow’s measurements are well-documented and include several levels of redundancy. Even when you account for potential deviation, they prove his hypothesis. How?

The primary issue was that the Rectilineator was designed poorly. The support columns were too close to the center, allowing the ends to sag even though the entire structure was made of solid mahogany. Morrow had tried to combat any potential sagging by attaching a metal brace — but it was secured at the ends, not the center, which wound up creating sagging. The deformation was small enough not to be noticed, but each additional section only compounded the initial error.

A secondary concern was that the results matched Morrow’s hypothesis and as a result of that bias, he saw no reason to go back and re-check his experimental design. At some point, though, Morrow seems to have realized his experiment had flaws and tried to convince the Koreshans to finance refinements to the Rectilineator and run another experiment. Teed, though, was satisfied with the existing results, primarily because he had nothing to gain and everything to lose from a re-run. Morrow, realizing his patron cared more for religion than science, quit the group. He still believed the Earth was hollow, but he no longer believed in Cyrus Reed Teed.

The next few years were rough for the Koreshan Unity. In 1897 Gustave Damkohler lost his faith in the new Messiah, and sued to recover his land, claiming he had been hypnotized by Teed. Damkohler’s lawyers tried to get Koreshan literature entered into the court record, making the case that they were a dangerous cult. Unfortunately for Damkohler, the Koreshans had already won the battle in the court of public opinion by being pleasant and supportive to their neighbors. In the end, he was able to claw back half of his property, which he sold off to fund his retirement.

In 1898, a bigger problem moved in just down. Notorious Spiritualist scam artist Ann O’Delia Diss Debar had tried to join the Koreshan Unity’s Chicago commune in 1895 after serving a seven-year sentence in Joliet Prison. She was bounced after a few weeks, but had apparently stolen a ton of their literature and used it to set up her own copycat cult, the Order of the Crystal Sea, just down the road. For a few months she tried to aggressively steal away Koreshans while simultaneously slandering Teed in the Fort Myers newspapers. Thankfully, at this point Debar’s name was mud, and she eventually had to pack up and leave for Europe.

The strain of operating two communes eventually proved too much for the Unity. When they lost their lease on Beth-Ophrah in 1903, the few remaining Chicago Koreshans were relocated to Estero, boosting its population to over 200.

In 1904 Teed decided that the commune should be officially incorporated as a town. That would allow them to use state tax money to improve the property, most notably the road and post office. To gather local support he allied with Philip Isaacs, the owner of the Fort Myers Press, agreeing that the Koreshans would vote for him as one block if he backed their incorporation. But even Isaacs couldn’t stop locals from noticing that the proposed city limits of Estero were about eight times larger than the land they controlled and included property they didn’t own as well as some land on the bottom of Estero Bay. The incorporation passed, but Estero was forced to scale back its actual city limits to a more reasonable size.

To celebrate, the Koreshan Unity finally completed construction of their Art Hall in 1905. It opened with an exhibit by an Aesthetic painter of some renown — Douglas Arthur Teed, the Messiah’s own son. After being abandoned by his father, Douglas had been taken in by a wealthy widow who encouraged his talents and sent him to art school in Europe. The exhibit was an attempt at reconciliation, and it failed miserably. Dr. Teed announced he would purchase some of the paintings for $7,500 but never actually paid for them. Douglas tried negotiating with his father, offering to take less than half that amount, or an equivalent value in goods and services. In the end he was forced to sue to get paid. The two never saw or spoke to each other again.

Theocrasis of the Theanthropos (1906-1909)

In 1906 the Koreshan Unity ran afoul of their one-time ally Philip Isaacs, now head of the local Democratic Party. Estero wanted a larger share of the county’s tax revenues for municipal improvements, but Isaacs was one of those Grover Norquist types who feels that any tax, no matter how small, is a tax too far. When Isaacs realized some of the Koreshans had crossed party lines to vote for Teddy Roosevelt in 1904, he required all voters in the Democratic Primary to sign a pledge asserting they’d never voted for a Republican. When the Koreshans refused to sign, he had their votes invalidated. It made the primary uncomfortably close, and for the first time the Koreshans realized how much power they could have voting as a block.

The Unity’s response was to cobble together a shaky coalition of Republicans, marginalized Democratic groups, Socialists, and other outsiders. Their “Progressive Liberty Party” ran a full slate of tickets against Isaac’s candidates that November and gave him a serious run for his money. They started their own weekly newspaper, The American Eagle, devoted entirely to attacking Isaacs and the Democratic party machine. They ran boisterous rallies all across Lee County, backed up by a thunderous brass band.

About six weeks before the election, one W.W. Pilling arrived in Fort Myers to join the Estero commune, but no one was there to meet him at the train station. He spent the night in a hotel run by one Colonel Sellers. The next morning someone from Estero called asking for Pilling, and was told by Mrs. Sellers that he wasn’t there. Mrs. Sellers meant that he had stepped out for a moment, but the caller apparently understood her response to mean that Pilling hadn’t arrived at all. When Pilling returned, Mrs. Sellers called Estero to let them know, and the voice on the other end of the line sounded confused. “I thought you said no one of that name was stopping there.”

Two weeks later, W. Ross Wallace, the Progressive Liberal candidate for county commissioner, spotted Colonel Sellers on the street and said hello. The Colonel, who seems to have been a barely-contained bundle of rage, accused Wallace of calling his wife a liar and started to beat the ever-living tar out of him. An utterly confused Wallace ran to the mayor and begged for help, but unsurprisingly the (Democratic) mayor was not inclined to give any. Wallace fled town until Sellers could calm down.

A few days later, Wallace arranged a meeting with Sellers to explain what had happened and apologize for any inadvertent offense. He also recruited local marshal S.W. Sanchez to mediate. As the three men conversed in front of Gilliam’s grocery, Dr. Teed noticed them and decided to butt in to the already tense conversation. It was a bad move, and while trying to play peacemaker he inadvertently called Sellers a liar. The Colonel’s hair-trigger temper went off again and he started pummeling Teed in the face. Marshal Sanchez (a Democrat) looked on impassively, intervening only when a knife was pulled.

Then Teed’s bodyguard, a young boxer named Richard Jentsch, arrived on the scene with a group of young Koreshans freshly arrived from Baltimore. They fought their way through the gathering crowd and knocked Sellers and Sanchez to the ground. At this point it became crazy brawl which only ended when the Koreshans were beaten senseless. Once they were subdued, Marshal Sanchez slapped the glasses off Teed’s face, accused the Koreshans of throwing the first punch, and threw them all in jail. Teed posted a $10 bond, and wisely chose to skip his court appearances the following Monday.

Teed was hung in effigy by angry Fort Myers residents, and the Progressive Liberal Party was soundly defeated on election day. (Actually, they’d done quite well in rural communities but were crushed in Fort Myers, which had more votes than the rest of the county combined.) Philip Isaacs celebrated by revoking Estero’s articles of incorporation, though that was later ruled unconstitutional.

After the beating Teed was in constant pain and confined to a wheelchair. For over a year he was confined to the commune and his condition was hidden from Koreshans outside of Estero. He could no longer lecture and traveled only once, to try and establish a commune in Washington, DC, but his condition worsened and he quickly returned to Florida. He spent his days as a bed-ridden invalid, dependent on his personal nurse to give him saltwater baths and electrotherapy treatments.

On the morning of December 22, 1908 Teed asked for a teaspoon of salt, declaring “Every sacrifice should be purified.” He had three small tastes of salt, and died an hour later.

Koreshans were elated, thinking Teed would rise from the dead by Christmas to usher in the new millennium. His body was quickly moved into a zinc bathtub and the community marveled as over the next few days it blackened and bloated. Some believers even fancied they could see his old body taking shallow breaths, or a new body forming just beneath the skin of the old.

Nothing spectacular or supernatural was happening: Teed’s body was just decomposing rapidly in the sweltering Florida heat. When county health officials got words of Teed’s passing a few days later, they rushed to Estero, hastily signed a death certificate, and forced the Koreshans to bury the body. The Unity built a simple stone tomb on Estero Island and dumped the bathtub with Teed’s body inside. The headstone had no birth or death dates, and inside the tomb they hid a note:

In compliance with the law, and only for such reason, the body of Cyrus R. Teed is placed in this stone vault. We, the disciples of Koresh, Shepherd, Stone of Israel, know that this sepulcher cannot hold his body, for he will overcome death, and in his immortal body will rise triumphant from the tomb.

Anastasia

Incorruptible Dissolution (1910-1982)

When, after several weeks, Teed’s immortal body still hadn’t risen triumphant from the tomb, the Koreshan Unity started poring over their sacred texts to figure out what might happen next. It turned out Teed’s descriptions of his “theocrasis” were vague and contradictory. Was it a physical transformation, a spiritual transformation, or both? Would it happen shortly? Had it already happened, and no one noticed?

If it had happened, Victoria Gratia should be the new leader. But if it hadn’t happened, was she still divine? And what if it never happened? Here Victoria’s personal unpopularity worked against her, and many Koreshans refused to recognize her authority. She eventual tired of fighting and left the commune to marry a dentist, Dr. Addison Graves.

Gustav Faber, Teed’s nurse, claimed that Teed has passed the divine spark to him shortly before dying, but no one believed him. A recent convert, Edgar Peissart, made the same claim, and they believed him even less because Peissart changed religions more often than he changed his clothes. (And also they had caught him out on Estero Island trying to conduct a seance with Teed’s corpse, which was tantamount to declaring that Teed was dead. Whoops.)

Some members of the Unity, including W. Ross Wallace, moved into Fort Myers proper and started a short-lived splinter group. Others turned to Ulysses Morrow to lead them, but he refused.

The mantle of leadership eventually settled on one of Teed’s longtime financial backers, Henry Silverfriend. No one ever believed Silverfriend was divine, but he was an able manager and kept the commune afloat during the lean years that followed. When Silverfriend grew feebleminded he was replaced by Allen Andrews, the son of Teed’s long-time confidant Dr. A.W.K. Andrews. No one liked Allen, but no one else wanted the responsibility, either.

By the 1930s the aging Unity could no longer participate in agriculture, but managed to survive off the revenues from their general store, gas station, and trailer park. The commune’s already small numbers started to dwindle, and only 55 full-time residents remained. The few Koreshans who didn’t live on the commune preferred to stay away, because they found the place decrepit and depressing.

Teed’s ideas continued to propagate, even thought the Unity no longer sent out missionaries. Most notably, German writers like Peter Bender corresponded with the Koreshans and expanded on Teed’s ideas to create a more complicated Hohlweltehre, or “Hollow Earth Doctrine.” Influenced by their writings, Adolf Hitler even sent a small fleet to the Baltic to look upwards with powerful telescopes and see if they could spot the movements of the British Navy in the Atlantic Ocean. (Okay, there’s no documentary evidence that ever happened, but it’s too juicy to not share.)

Teed’s works also found their way into the hands of a young Jewish school teacher, Hedwig Michel. A colleague handed her a copy of The Cellular Cosmogony, which she found fascinating. When she was forced to flee the pogroms in Germany, she wrote to the Koreshan Unity and was invited to come stay with them.

When Michel arrived in Estero, there were only about a dozen Koreshans left and the commune was in serious disrepair. Allen Andrews was more interested in driving fast cars and writing cranky letters to the Fort Myers Press than actually running the place. Fires and other disasters destroyed buildings one by one, and no one made a move to replace or repair them.

A horrified Michel organized the ouster of Allen and the two of them spent years fighting for control of Estero. Michael was ultimately triumphant, but she too practiced benign neglect in her management of the community. She kept the place running out of gratitude for the Koreshans’ hospitality, not because she was a believer. In 1961 she deeded the commune’s land to the state for historical preservation, provided that Michel and the three remaining Koreshans could live on it until their death.

When Apollo 11 landed on the moon in 1969, the last surviving Koreshan, 90 year old Vera Newcomb, finally lost her faith. But she had nowhere else to go, and died on the commune in 1974. Michel hung on for another eight years, finally passing in 1982. Today, you can visit the surviving structures at Koreshan State Park.

As for Dr. Cyrus Reed Teed himself, well, in October 1921 a mighty hurricane hit Estero Island and washed his mausoleum into the Gulf. The headstone floated ashore afterwards, but everything else was lost. Maybe Teed is still floating out there in his zinc bathtub, waiting for the right moment to return and save us all.

Connections

During his lifetime Dr. Cyrus Reed Teed was often used as a point of comparison for other cult leaders, including “Prince” Michael K. Mills of the House of Israel and “King” Ben Purnell of the House of David(“Exceeding Great”).

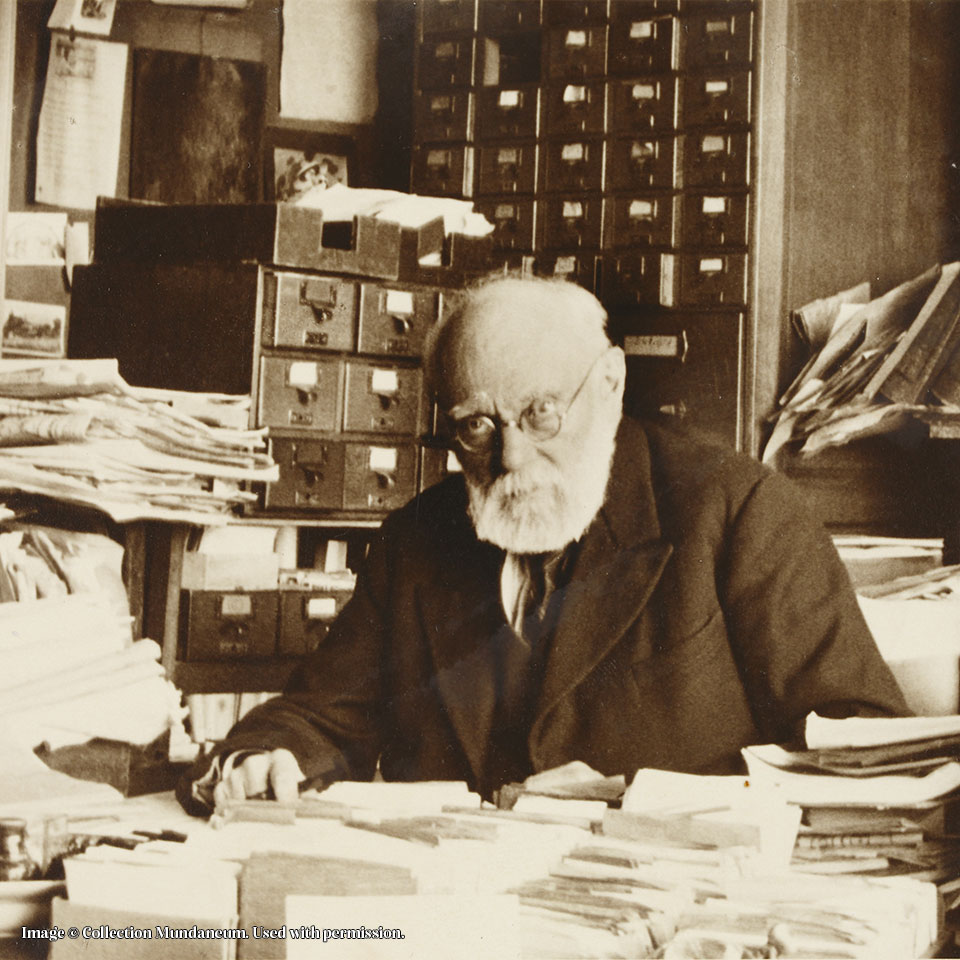

The concept of focusing spiritual energies into a single location was common in Theosophical circles; librarian and utopian Paul Otlet even included a “Sacrarium” designed to collect these energies in designs for a World City (“Steampunk Google and the World City”).

Dr. Teed was a great admirer of George Rapp and his Harmony Society, and even tried to merge them into his proposed union of celibate societies (“Hold Fast What Thou Hast” and “That No Man Take Thy Crown”).

Spiritualist scam artist Ann O’Delia Diss Debar briefly tried to join the Koreshan Unity, and later directly competed with them by opening her own copycat commune right next door (“Spirit Princess”).

Ulysses Grant Morrow studied geodetics so he could prove that we lived in the center of a hollow earth. Geodetics can also be used to determine the exact geographic center of an area. (“The Centers of All Things”).

Dr. Teed is prominently featured in Martin Gardner’s seminal Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. You know who else is prominently featured in Fads and Fallacies? Electron-denier Bayard Peakes (“I’m the Naughty Boy”), chromotherapist Dr. Dinshah Ghadiali, (“Normalating”), hollow Earth prophet Wilbur Glenn Voliva (“Marching to Shibboleth”), and science fiction author Richard Sharpe Shaver (“A Warning to Future Man”).

Sources

- “Cyrus Teed.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyrus_Teed Accessed 1/1/2020.

- “Eclectic medicine.” Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eclectic_medicine Accessed 1/1/2020.

- Fine, Howard. “The Koreshan Unity: The Chicago Years of a Utopian Community.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, Vol 68, No. 3 (June 1975).

- Gardner, Martin. Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science. New York: Dover, 1953.

- Jenkins, Philip. Mystics and Messiahs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Koszulinski, Georg. Last Stop Flamingo. 2014.

- Mackle, Elliott. “Cyrus Teed and the Lee County Elections of 1906.” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol 57, No 1 (July 1978).

- Melton, J. Gordon (ed). Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology (4th ed). Detroit: Gale Research, 1996.

- Morris, Adam. American Messiahs: False Prophets of a Damned Nation. New York: Liveright, 2019.

- Millner, Lyn. The Allure of Immortality: An American Cult, a Florida Swamp, and a Renegade Prophet. Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2015.

- Simanek, Donald. “Turning the Universe Inside Out: Ulysses Grant Morrow’s Naples Experiment.” https://www.lockhaven.edu/~dsimanek/hollow/morrow.htm Accessed 1/14/2020.

- Sinclair, Upton. The Profits of Religion. Pasadena: self-published, 1917.

- Standish, David. Hollow Earth. Cambridge: Da Capo Press, 2006.

- Tarlow, Sarah A. “Representing Utopia: The Case of Cyrus Teed’s Koreshan Unity Settelement.” Historical Archaelogy, Vol 40 No 1.

- Teed, Cyrus Reed and Morrow, Ulysses Grant. The Cellular Cosmogony. Estero, FL: Guiding Star Publishing, 1905.

- Teed, Cyrus Reed. The Illumination of Koresh. Chicago: Guiding Star Publishing, 1900.

- Teed, Cyrus Reed. The Immortal Manhood. Chicago: Guiding Star Publishing, 1902.

- Thomas, Amy. “The Adventure of the Koreshan Unity.” Sherlock Holmes: The Sign of Seven. New York: Titan Books, 2019.

- “The Prophet Cyrus.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 11 Aug 1884.

- “Cyrus, Son of Jesse.” Chicago Tribune, 10 Apr 1887.

- “Held to the grand jury.” Chicago Tribune, 23 Feb 1888.

- “Blasphemy and folly.” Chicago Tribune, 20 Jul 1890.

- “A new religion.” San Francisco Chronicle, 27 Nov 1890.

- “Is called the Messiah.” San Francisco Chronicle, 16 Jan 1891.

- “Teed’s trip to heaven.” Chicago Tribune, 17 May 1891.

- “Doctor Teed is there.” Pittsburgh Dispatch, 22 Oct 1891.

- Ferguson, Lillian. “Devilish Dr. Teed, the Lady Lurer.” San Francisco Examiner, 17 Sep 1899.

- “Messiah Teed maybe ousted.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 13 Oct 1901.

- “‘Koresh’s’ tomb and body swept into Gulf.” Tampa Tribune, 13 Nov 1921.

- “Koreshan old guard denied receivership.” Fort Meyers News-Press, 30 Nov 1947.

- “Two Koreshan Unity factions argue over $500,000 stake.” Tampa Tribune, 19 Nov 1948.

- Damkohler, Elwin. “Early settlement of beach pictured by E.E. Damkohler.” Fort Meyers News-Press, 20 Feb 1952.

- Barry, Rick. “Koreshan faith preserved in community.” Tampa Tribune, 16 Aug 1982.

Links

- Adam Morris, author of American Messiahs

- The Constant: “The Foolkiller, Part 2”

- Florida Gulf Coast University Digital Repository

- The Flaming Sword at the International Association for the Preservation of Spiritualist and Occult Periodicals

- Koreshan State Park

- Lyn Millner, author of The Allure of Immortality

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: