Milking It for All It’s Worth

let's get saucy and talk about béchamel

We’re going to try something a little different today. We’re flying live without a script, we just have an outline and I will type a transcript from it later. This is #13, of course, here in the secret recording bunker, and we’re joined today by #7.

Hello!

And we’re going to start talking about a subject that’s near and dear to her heart, the… well, what do you want to call them?

We’ll call them the grand sauces.

The grand sauces. And what are the grand sauces?

The grand sauces are the base sauces, of which there are five, that all other sauces can be derived from.

This is a concept from where, exactly?

The fancy French.

So, it’s a concept from French cooking.

Cuisine, yes.

Cuisine, chef. Let me ask, we’re not going to talk about all of them today, obviously, because we would be here forever…

Well, obviously you’re “milking the situation” so hence we shall talk about sauce béchamel.

Béchamel sauce. I know virtually nothing about béchamel except that it’s rich and creamy. What’s the history of it? Where does it come from?

Béchamel was first known about… It’s been around for ages if not centuries. One of the first chefs, [François Pierre] La Varenne, who was french, mid-1600s, he described it pretty much as a velouté, which is a white stock, with the addition of cream and thickened.

Now, what’s a white stock, is that made from..?

It’s made from meats like poultry or pork, basically white meats. You can also use fish stock.

Okay, so not beef…

Not veal, not beef.

All I know about Varenne is that apparently he was the one who named this béchamel.

He, as he was wont to do, being the ass-kisser he was, liked to name things after people in his life. And béchamel was a sauce named for… what was his name again?

Let’s see, here in my notes it says he is named after, where is it…

Was it a marquis?

Yes. Louis de Béchameil, Marquis de Nointel, who was a tax farmer, art lover, and chief steward to Louis XIV.

So as any smart chef at that time in his life would have, he kissed the ass of someone who had influence in court.

Yes, actually, I have a great quote here from Béchameil’s contemporary the Duc d’Ecars:

That little Béchameil has all the luck. I was serving chicken a la crème twenty years before he was born and no one’s named a sauce after me!

So, La Varenne is the first person to put the name to the sauce.

Correct.

And that’s when, mid-17th century?

Yes.

What would have the preparation been like? You said it was basically a velouté that was then…

They have a very, very, very detailed time-consuming preparation for their veloutés or stock, with the addition of spices and herbs. Varenne was very frugal and tried to switch it up by using more local products instead of all the herbs and spices from far away places. So instead of spending all that expensive money… [laughs] That’s funny, I’m sorry.

Expensive money. We have a whole episode about expensive money, if you want to listen to the first episode of Series 2, “Cold Hard Cash”, which is about the rai stones of Yap.

[laughs] It was just expensive. All chefs are cheap bastards. He would have used local products as much as possible instead of spending extra on getting something from far away when people probably couldn’t discern the flavor differences.

Since we’re talking the late 17th, early 18th century this is the point in time when France is at the peak of her imperial powers. So I’m assuming their sauces and everything, their preparations are just getting ever more rich and extravagant during this period.

Especially considering how the courts were so decadent. Everyone was competing with each other, not only to rise in favor with the king and become more influential. One of those ways was to have salons and party.

The way to you monarch’s heart is through his stomach, I guess.

We know that from King Henry VIII.

Obviously at some point… Well, not at some point, in 1789 the French get sick of this whole deal and we the French Revolution, which I’m sure is not great if you are a chef in one of these rich person’s kitchens.

It’s an interesting subnote, that was actually the time, during the Revolution, when restaurants become widely in use.

I guess that makes sense. You have all these chefs that are being displaced from rich people’s kitchens, and they need to do something…

To earn money. That evil devil money.

I imagine it’s not quite the same cuisine. You can’t throw fifty hams at a single sauce for a single meal, right?

No. They would use whatever product was on hand and local, because they couldn’t afford to ship things in from India or China.

That’s about the time we get [Antoine-Marie] Carême coming in, correct?

Correct.

And Carême is the person who comes up with the concept of the mother sauces, and he makes béchamel one of his mother sauces, correct?

Correct. He only had four, though.

And what would they be.

Espagnole, which is a brown one, béchamel, velouté, and… hollandaise?

Espagnole, velouté, béchamel, and allemande.

Allemande. I always forget allemande because in today’s cuisine it is considered part of the béchamel family.

We know béchamel is milk-based, what are the other three? What’s an espagnole?

Espagnole is made from a brown stock, which is your beef, veal, cooked, rendered roasted in an oven to get colored. You then have velouté, poultry and fish, which the french call a fûmer, which are thickened with a roux. You also have tomate, or tomato sauce, which is a vegetable-based sauce, and hollandaise, which is the egg-based sauce.

Let’s talk about our modern roux recipe… not roux, let’s talk about our modern béchamel recipe. That comes from Escoffier. From my understanding it’s literally just “mix some milk with a white roux.“

Correct. A white roux is basically just equal parts butter and flour, cooked over a medium flame, maybe less depending on how attentive you are, very lightly, just enough to get the flour developing the proteins in it, I guess, to heat them up, some chemical equation, I’m sorry, I’m not Harold McGee, I don’t know the science…

Oh, Harold McGee himself basically says you are breaking down the starches to remove the insoluble gluten fibers from the other starches so they can bind with the milk.

There you go.

From the mouth of McGee.

From that stage, you take warm milk and you add the roux and that ends up thickening it. You do that until it comes to a boil.

The difference between Escoffier and Carême’s version is straining, skimming. The way our society’s foods have been refined there are less impurities in them now. That’s less of a worry these days.

And I imagine Carême’s has much more ingredients in terms of roasted vegetables and meat products that would need to be skimmed out after cooking.

I don’t know exactly what they did then, only what is written. One thing about a lot of those old recipes is that in the books people give ingredients and say “stir” but they don’t give further directions. They don’t say “you need to strain this” or “you need to do this amount or that amoung.” It’s just “a dash of this” but you don’t know if a dash… Standardization didn’t really start happening until the time of Escoffier.

I know I’ve seen a bunch of these old cookbooks and they don’t even bother to list quantities of ingredients. They never tell you it’s a tablespoon, they just say “add nutmeg” and you’re expected to know how much nutmeg that is.

Oh, it drives me crazy. My great-uncle was an executive chef and I’ve inherited his book of recipes. All it lists is the ingredients. So no procedure at all.

See, I’m anal, that’s my nightmare, being forced to go into a recipe without having anything at all.

They expected you to know procedures for everything.

We’ve got our béchamel sauce, which is milk mixed with flour and a little butter…

Equal parts flour and butter.

I am going to have to say Harold McGee says it has a “pleasantly neutral” flavor but that also sounds pretty bland to me. I imagine the real fun comes in making the derivative sauces, the child sauces.

I beg to differ. I think the mother sauce, as it’s known, as well as the grand, can be very neutral but considering that it also has salt, pepper, and nutmeg — white pepper, not black pepper — it does have a flavor. It is very creamy but it does have hints of otherness, to say that weirdly. The most popular use of this sauce is in lasagna.

I guess I really didn’t think of it that way.

It is traditional. Pasta sheets, the béchamel, and tomato, and that’s it. And the tomato mixed with the béchamel makes it almost what we consider now a vodka sauce in a way. It’s subtle, but the addition of the other sauces really helps define…

And I guess being neutral in flavor makes it adaptable.

That’s the consideration of all the mother sauces.

What are some of the other sauces you would make from a béchamel base?

The most popular one would probably be the Mornay, which is what we use for fettuccine alfredo, mac and cheese. Nacho cheese sauce is a Mornay sauce, just different types of cheese.

I’m assuming we just add cheese and spices to our béchamel until it gets to the right consistency to make a Mornay?

Correct. A fettuccine alfredo, the alfredo sauce is a specific type of cheeses compared to a mac and cheese, a traditional Mornay, is usually Swiss, maybe Parmesan added to it, whereas fettucine alfredo…

Your meltier cheeses.

Different cheeses. Parmesan seems to add the saltiness so you’re not adding extra salt. That’s one reason people like using Parmesan. It’s interesting enough that there are plenty of Mornay sauces that also use blue cheese mixed with parmesan and cheddars because it adds…

I hate to say this, but the most recent edition of Doritos, their cheese powder has blue cheese in it. You can taste it if you know your cheeses. Weird fact.

The Cool Ranch, I’m assuming?

No, this is the regular nacho cheese flavor. It adds a depth to it that the old Doritos — because I can distinctly remember thinking about this when the did the changeover when I was in culinary school.

Okay. I’ll have to keep an eye out for that next time I order my Tacos Locos. What other sauces would you be able to make with béchamel?

Well, there is the souvise, which is pureed onions…

Is that “souvise” or “soubise”?

Soubise. Yeah, my French sucks, sorry.

I’m surprised they don’t make you take three years of French in culinary school.

I didn’t go to the CIA, darling. Well, that’s not even that long anyway. One of the other main sauces is the Nanuta, which is a seafood addition to the Mornay.

(She meant “Nantua” sauce.)

Really? What kind of cuisine does that come from, because that doesn’t sound French to me.

I’m probably really horribly saying it incorrectly, but it is French also. The French and their weird…

What kind of dish would you put that sauce on?

You could definitely use it with various sides, like asparagus or other vegetables, but you could also use it with various seafoods to enhance the flavor of the seafoods itself. If you have a flounder or a sole and you want to add shrimp… I believe it adds a lot of shrimp to it, sou you could add a shrimp flavor to it and just enhance it a bit. Some of the main uses of these béchamel is in casseroles.

The “cream of” soups that the one soup company is known for, cream of mushroom, cream of chicken, though it’s a velouté base it’s still cream-based too so it almost harkens back to Carême. But that’s what we make all the casseroles from.

Do you have any thoughts or observations about béchamel sauce that you’d like to share with us before we call it a recording day?

Don’t be afraid to try to make it. It’s really simple. You can use milk or cream depending on the richness you want to go for. And if you get the roux a little dark that’s okay. It’ll just add a little nuttiness to the flavor. But if you go all the way to brown roux, save it for your gumbo or brown sauce.

Well, thank you. Thank you, Chef #7, we really appreciate that.

You’re quite welcome.

We’ll have some extra content here on our website. We’ll have a recipe for béchamel sauce provided by #7. Since we’re trapped in the secret recording bunker for the foreseeable future during this quarantine, when are you going to make me some béchamel sauce?

Okay, you guys can’t see this on the radio, but she’s giving me the old double deuce, so let’s call it a day.

Errata

(All corrections from the errata have been incorporated into this article, but not into the published audio.)

Recipe (Traditional)

When the velouté is thick and just at the moment you are going to bind it with a liaison of yolks and cream, pour into the velouté, little by little, thick cream and then you reduce this béchamel, taking care to stir with a wooden spoon to make sure the sauce does not stick to the bottom of the pan. When it is simmered down to the desired consistency it should just coat lightly the garnish for which it is intended; then you remove it from the fire, add to it a piece of butter the size of a walnut and a few tablespoons of very thick double cream to make it whiter. Then add a pinch of grated nutmeg, pass it through a white tamis and keep hot in a bain-marie.

Recipe (Modern)

Melt 5 tablespoons butter in a large saucepan over medium heat. Once melted, stir in 1/4 cup all-purpose flour until smooth. Continue stirring as the flour cooks to a light, golden, sandy color, about 7 minutes.

Increase heat to medium-high and slowly whisk in 1 quart milk until thickened by the roux. Bring to a gentle simmer, then reduce heat to medium-low and continue simmering until the flour has softened and not longer tastes gritty, 10 to 20 minutes.

Season with 2 tablespoons salt and 1/4 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg.

Connections

François Pierre La Varenne wrote down the first known recipe for béchamel sauce, which he named after Louis de Béchameil, Marquis de Nointel. He had a habit of doing that; he also created duxelles, which are named after Nicolas Chalon du Blé, marquis d’Uxelles, maréchal de France (“You Are Who You Eat”).

Sources

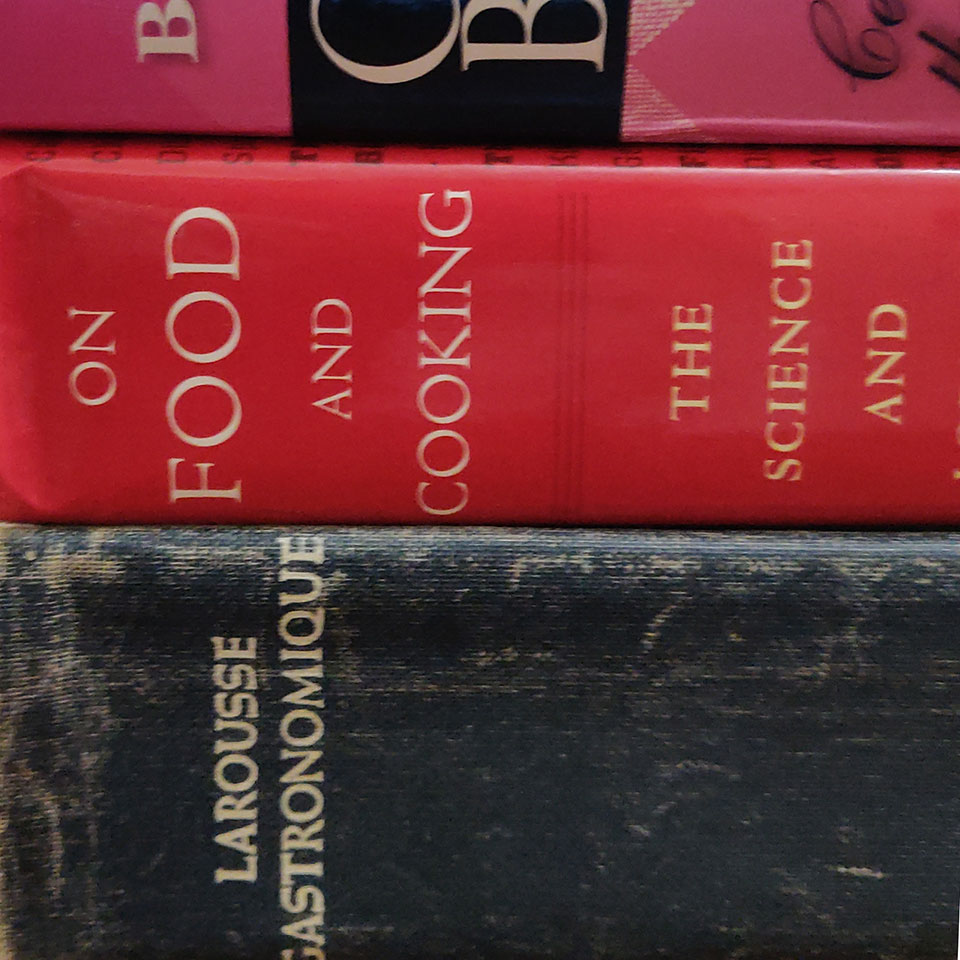

- Carême, Marie-Antoine. The Art of French Cuisine in the Nineteenth Century. Paris: self-published, 1833.

- Escoffier, Auguste. The Complete Guide to the Art of Modern Cookery. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1979.

- La Varenne, François Pierre. The French Cook. Lyon: Pierre David, 1651.

- McGee, Harold. On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (2nd edition). New York: Scribner, 2004.

- Montagné, Prosper. Larousse Gastronomique. Translated by Nina Froud, et. al. New York: Crown Publishers, 1961.

Categories

Tags

Published

First Published:

Last Edited: